Research conducted by Answers in Genesis staff scientists or sponsored by Answers in Genesis is funded solely by supporters’ donations.

Abstract

I’m again grateful to Frello, this time for the length and detail of his follow-up review. In this second critique, Frello begins to concede some of the major points of Replacing Darwin. In addition, Frello is unable to mount a scientific challenge to the remaining theses. This is helpful progress in our discussion, and it argues for the strength of the science in Replacing Darwin.

Overview

Stefan Frello, a PhD biologist and evolutionist, previously wrote a formal critique (Frello 2018a) of Replacing Darwin (Jeanson 2017c), and I responded to his criticisms (Jeanson 2018). In our first exchange over the claims in Replacing Darwin—The New Origin of Species, I documented the fact that Frello’s objections fell far short of the type of scientific critique that might reveal real flaws in my analyses. Specifically, I documented the fact that Frello avoided directly engaging the main points of my book. I also showed that his criticisms failed to uncover errors in Replacing Darwin because Frello’s objections generally amounted to nothing more than (1) statements of untested hypotheses as fact and/or (2) misrepresentations of claims in Replacing Darwin. Surprisingly, in some cases, Frello’s attempted objections actually helped underscore my point.

This second critique (Frello 2018b) primarily responds to my published rejoinders (Jeanson 2018). Since we’re past the first stage of our exchange, I recognize the difficulty that readers might have in following the sequence of statements in each paper. To ease this challenge, I will be reprinting Frello’s most recent critique in full (in small capitals), with my responses interspersed throughout.

Frello: Introduction

I used to think that when creationists talked about the discussion between creationism and evolution as a clash between two worldviews, they were wrong. Jeanson has helped me change my mind. It is a clash between worldviews: the scientific and the religious. To make it short: in science, no text is infallible. Everything has to be tested against observation. In (some versions of) religion, there is an infallible text (in Christian creationism, of course it is the Bible). If an observation contradicts the text, the observation is by definition wrong. This simple fact leaves creationism as unscientific!

Here, Frello makes a sweeping claim against YEC—without citing any evidence to justify his claim. In particular, he cites no evidence from Replacing Darwin to support his views. In contrast to Frello’s assertions, Replacing Darwin contains many testable, falsifiable claims (e.g., see especially predictions on rates of speciation in Chapter 6, predictions on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) patterns, function, and mutation rates in Chapter 7, and predictions on nuclear DNA patterns and function in Chapter 8). The fact that Replacing Darwin contains predictions that can be falsified immediately reveals Frello’s criticism to be a caricature of my views.

In other words, Frello begins his critique by accusing me of fitting facts to conclusions . . . and he seems to support his contention by fitting facts to conclusions.

A little food for thought: Jeanson’s response is about four times the length of my review! You could say that refusing nonsense with truth is more time-consuming than stating nonsense. Perhaps refusing truth with nonsense is even more time-consuming. It should be easier to argue in favor of truth than to have to make up flawed arguments in favor of nonsense!

I find this criticism ironic—particularly since it is printed in the second round of Frello’s critique, a critique that is almost twice the length of Frello’s first. Why would Frello need an extra published critique to refute Replacing Darwin? Is it because refuting “truth with nonsense is even more time-consuming” than a single, shorter paper would require?

I find additional irony in Frello’s statement: In my first response (Jeanson 2018), I documented the fact that Frello’s arguments contained severe misrepresentations of my Replacing Darwin. To clarify what the book actually said, I had to reprint large blocks of text from the book. Consequently, I agree that refuting Frello’s particular brand of “nonsense with truth is more time-consuming than stating nonsense.”

I urge any reader, creationist or otherwise, to contact me if they need clarification of one or more points in this, rather short, response.

In the previous paragraph, Frello derided the length of my response to his review. However, rather than put into practice the standards to which he holds me, Frello did not stop at a single critique and, instead, wrote a second—and urged readers to hear even more of his thoughts outside of this forum. Does Frello see the irony of his practice?

Any clarification of genetic terms or principles can be studied in Jeanson’s book, which has a brilliant account of genetics.

This is a kind compliment.

I have to admit that I should have been more systematic in my review. Too often, I do not explicitly mention what chapter I am talking about. This causes some confusion.

I appreciate this concession.

I have tried to keep my reply short—not that I have succeeded. Instead of taking Jeanson’s objection point by point, I’ll make some general comments on why I do not think Jeanson has much new to offer. Some points, though, I feel need more thorough comments.

As we’ll soon see, I think Frello could help his case by making his review longer—and by engaging my published points in a systematic manner. Does Frello avoid this straightforward strategy because he’s just limited himself (see above) by criticizing lengthy articles, thereby logically preventing him from writing a lengthy critique?

To fully appreciate this reply, first read my review (Frello 2018) and Jeanson’s response (Jeanson 2018).

I concur with Frello’s exhortation to the reader.

Here is an introduction to a guiding principle in science, which is useful to know, and which the reader is invited to use whenever it seems appropriate: Occam’s razor: A principle stating that when choosing among alternative theories, we should prefer the one with fewest arbitrary assumptions. Of course, we should accept assumptions that seem well supported. In genetics, one such extremely well supported assumption is the theory of the transcription-translation system from DNA to protein. Occam’s razor does not state that there always will be one, and only one, such theory. It might depend on what you accept as well supported assumptions.

Let’s keep reading to see if Frello consistently applies this principle.

Frello: On “Introduction and Overview”

Jeanson refers to our discussion about the reliability of ancient mtDNA (Frello 2017a, b; Jeanson 2017a, b). I urge our readers to read the articles, and judge for themselves if I have “revealed the deficiency of [my] best anti-YEC claims” as Jeanson will have it. In Frello 2017a and Jeanson 2017a special attention should be paid to the terms “contamination” and “degradation.” In Jeanson 2017b, special attention should be paid to considering whether Jeanson actually argues against my suggestion in Frello 2017b (to confront the experts within the field of ancient human DNA).

Again, I concur with Frello’s exhortation to the reader; I think the reader will find our exchanges very illuminating.

Frello: On “Frello’s General Claims”

In short Jeanson summarizes the three parts of his book as follows:

1. The question of origin of species is fundamentally a genetic question. That’s why genetics is such an important tool in the study of evolution. I fully agree, which should be clear from my review. Not knowing genetics, Darwin took a massive scientific risk, when he published On the Origin of Species. I do not argue against that.

I’m pleased to see that Frello concedes the first major point of Replacing Darwin.

2. Darwin’s 1859 data are mostly irrelevant today. So what!

“So what!” is an interesting response to my claim about Darwin’s evidences being irrelevant—evidences that constitute some of the primary textbook evidences for evolution to this day.

YEC endorses migration as an explanation for biogeography. I comment on that.

YEC endorses speciation. I comment on that.

YEC’s explanation for the pattern of groupings of life have matured. I comment on that.

Consider the following: Frello’s initial critique invented its own outline to refute Part II of my book. In theory, this approach to a book review could work. However, our previous exchange (Frello 2018a; Jeanson 2018) showed that the substance of the critique within Frello’s invented outline failed to engage large sections of Part II of my book. Thus, though Frello commented on some topics touched upon in Part II of Replacing Darwin, he still failed to wrestle with the larger theses.

In other words, the structure of Frello’s critique foreshadows the deficiencies in his arguments.

3. YEC outstrips evolution in genetics. I comment on that.

The rest of point 3 is a clarification of this statement.

Why Jeanson calls these comments (the vast majority of the review) a side step from direct confrontation of the main claims of his book, is beyond me.

With respect to Part II of Replacing Darwin, see comments above. With respect to Part III, a similar conclusion follows. As with Part II, Frello’s initial critique invented its own outline in an attempt to engage Part III of my book. Again, as with Part II, the previous exchange (Frello 2018a; Jeanson 2018) shows that substance of the critique within Frello’s invented outline ignored or misrepresented large sections of Part III of my book.

I invite the reader to read Frello’s previous review (Frello 2018a) and my reply (Jeanson 2018) and judge for themselves whether Frello engaged the main points of my book. In the meantime, in this critique, I’m pleased to see that Frello has explicitly conceded at least one of the main points of Replacing Darwin.

Frello: On “Frello’s Claims About Biogeography.”

Here Jeanson goes to some length in explaining how the situation was in 1859. Except that Darwin used biogeography as one of his arguments in favor of evolution, the situation back then is not very important. For example, Jeanson repeatedly mentions species fixity as one of the ideas creationists have given up. In my review, I do not mention fixity at all. Who cares about outdated ideas?

In answer to Frello’s question, Frello should not care about outdated ideas—unless they are the central focus of a chapter that Frello is trying to critique. What was the central focus of Chapter 4 (“The Riddle of Geography”), the chapter that covers biogeography? The opening sentences read as follows:

If Darwin had no knowledge of genetics, how could he write a book on the origin of species? If genetic data were absent from his thesis, then how could he have made any semblance of a scientific argument for the origin of species? Furthermore, why did his arguments gain such traction in the scientific community? (p.107).

The rest of Chapter 4 answers these questions by giving the history of the conflict. Since the history of the debate over explanations for biogeography is the central focus of Chapter 4, it’s all the more important for Frello to care about “outdated” ideas.

How could Frello have missed the main point of Chapter 4?

Jeanson complains about my negligence in not reading the references found in an Endnote to Chapter 4.

Actually, my response wasn’t a complaint at all (see Jeanson 2018, and see below). I’m disappointed that Frello would characterize it this way.

Sorry Dr. Jeanson. If you have an important argument, do not put it in an Endnote, and especially not in references to which you only give a useless four-line review. That kind of trap is telling about Jeanson’s strategy. What Jeanson is actually asking his reader is to read 400 endnotes and look up and read hundreds of papers, webpages and other references to see if some important clue was hidden somewhere. Hardly the strategy of a person who honestly wants to inform his reader.

Frello appears to have two main criticisms in this paragraph. First, Frello thinks my practice of putting technical comments and references in the Endnotes is unfair/bad practice. He thinks important arguments should be in the main text. Second, Frello thinks my expectation that critics read “400 endnotes and look up and read hundreds of papers, webpages and other reference” is dishonest. He thinks I’m hiding clues from the reader.

In fact, both of these criticisms stem from an error that we identified earlier—his failure to grasp the main point of Chapter 4 (The Riddle of Biogeography). As I discussed above, the main purpose of Chapter 4 (The Riddle of Biogeography) is to give the history of debate over biogeography. Chapter 4 walks the reader through this history with all the main historical arguments included. I don’t omit the key arguments or the key data. Thus, my important arguments are in the main text. To understand and follow my conclusions, everything the reader needs to follow the history is in the main text.

With respect to the modern controversy over biogeography, I pushed the debate into the Endnotes. In our previous exchange (Jeanson 2018), I explained several reasons why. For one:

Unlike the nineteenth century, the twenty-first century debate is multidisciplinary. It involves the fields of plate tectonics, radiometric dating, geologic sedimentation, historical climatology, paleontology, biological migration, genetics, and the like. Currently, neither the creationist position nor the evolutionary model has a consistent, comprehensive, discipline-wide explanation for biogeography (i.e., see Chapters 7–10 of my book which reveal just a few of the shortcomings of the evolutionary positions in many of these fields). In other words, if Frello wants to take up the topic of biogeography and have a debate, he must synthesize data from plate tectonics, radiometric dating, geologic sedimentation, historical climatology, paleontology, biological migration, and genetics—something he never attempts to do (p. 65).

In addition:

The 21st century debate is much more complex. Modern creationists invoke even more hypotheses than the creationists of 1859. Specifically, in some cases (i.e., the New World primates or Malagasy primates), modern creationists might indeed invoke common ancestry! . . . Other hypotheses include historical contingency (i.e., effects of the ice age on land connections among continents, which might explain the partial endemism of marsupials to Australia), biological function (i.e., differential migration rates), competition among “kinds” (i.e., this a subset of explanations under the category of biological function), and differential extinction among “kinds” (p. 65).

Thus, given the scope and structure of the entire book, I saw little use in having an entire chapter on the unresolved modern controversy surrounding biogeography. Instead, I moved it to the Endnotes where dedicated readers could find the references needed to explore the topic and research it themselves to their own satisfaction.

Nevertheless, in his first critique (Frello 2018a), Frello tried to engage Chapter 4 (The Riddle of Geography) by challenging the modern creationist explanation for biogeography in all its full details. This is the “important argument” that Frello thinks I unfairly put in the Endnotes. Yet, as we’ve just observed, this important argument was not relevant to the purpose of Chapter 4.

If so, then why is Frello objecting? Let’s pause and reflect on the following observations:

- Frello’s critique missed (and continues to miss) the main point of Chapter 4.

- Instead, Frello’s critique attacked a point that Chapter 4 barely touches.

- When I pointed this out, Frello refused to admit his failure to grasp the main argument.

- Instead, Frello seems to attack Replacing Darwin again . . . for not containing a chapter that addresses the objection Frello raised.

Frello has adopted an unusual strategy to critique a scientific claim.

Unusual strategies aside, let’s reconsider his objections: Should my book have had more explicit treatment of modern biogeography? In other words, is Frello justified in stating that my book hides things relevant to the larger discussion by placing them in the Endnotes? Even if Frello grants that modern biogeography doesn’t fit the purpose of Chapter 4, could he still rightly object that familiarity with details and papers cited in the Endnotes is not a fair standard to which to hold him?

For perspective, consider the fact that the practice of Replacing Darwin is similar to the practice of Nature, Science, and Cell—the leading peer-reviewed science journals in the world. Currently, the print versions of these journals typically contain the Introduction, Results, and Discussion sections for each paper they publish. The key technical details— the Methods section for each paper—are usually dumped off into an online-only Supplemental Data section or pdf file. This is not hiding key clues. Rather, it saves print space, and it makes the main text of the article flow better. Thus, it seems that Frello has a problem, not just with my book, but with an industry-wide practice.

Consequently, if Frello wants to call my practice dishonest, then he must also impugn the character of scientific publishing in general. I don’t think Frello wishes to go in this direction. If he did, it would undermine his reliance on the mainstream peer-reviewed literature as the basis for his evolutionary claims.

For the record and for the future, I’m more than happy to discuss modern biogeography. However, as I stated in our previous exchange (Jeanson 2018), “the 21st century debate is multidisciplinary,” and “if Frello wants to take up the topic of biogeography and have a debate, he must synthesize data from plate tectonics, radiometric dating, geologic sedimentation, historical climatology, paleontology, biological migration, and genetics—something he” has yet to attempt.

I think Jeanson’s statement “neither the creationist position nor the evolutionary model has a consistent, comprehensive, discipline-wide explanation for biogeography” is fair. Nothing in my review talks against this view.

I am pleased to see Frello concede this point. It represents a significant departure from his initial claim that “Jeanson fails to account for biogeography, while the topic is among Darwin’s original arguments in favor of evolution.”

From Jeanson’s YEC point of view, it is a “historical contingency” that of 19 families of marsupials, 17 are endemic to Australia and the nearby Islands! I call it a “coincidence” to Jeanson’s discomfort.

First: Historical contingency is one of many hypotheses that could explain the endemism of certain marsupials to Australia. I repeat from our last exchange (Jeanson 2018):

Other hypotheses include historical contingency (i.e., effects of the ice age on land connections among continents, which might explain the partial endemism of marsupials to Australia) (p. 65, emphasis added).

See longer quote above for the context in which this quote occurs—context which lists several other hypotheses.

Second: The term “coincidence” causes me no discomfort. I recognized that it “implies a probabilistic component”—which was very helpful in stimulating my own thinking on and exploration of this topic. Therefore, I’m actually grateful for Frello’s use of the term. I hereby thank him publicly.

I point to two more striking facts: Four different families of Monkeys (the group Platyrrhini) ended up in South America. Four different families of Lemurs (the group Lemuriformes) all ended up on Madagascar! In Chapter 10, Jeanson equates family with biblical kind, but here Jeanson’s answer is that a family is not necessarily equal to kind. The identification of kinds is still a [guess]work in progress. More on that in the section Speciation.

Once again, Frello’s statements betray his less-than-rigorous reading of my book. Let’s observe what I actually said about the biblical kinds. In Chapter 5 of Replacing Darwin, I state:

Modern creationists do not equate min [the transliteration of the Hebrew term typically translated ‘kind’] with species. Instead, whether mammals, reptiles, or birds, min appear to be best approximated by the classification level of family or order.25 Since this rule of thumb seems to apply across vertebrate classes, the fish and amphibian min would also appear to be best approximated by the classification level of family or order. Thus, applying this principle back to the text of Genesis, modern creationists conclude that Noah brought on the Ark representatives of each family or order, not of each species . . . Since vertebrate families and orders today are typically composed of more than one species, modern creationists endorse the formation of new species within vertebrate families and orders (at least within those families and orders where hybridization tests have tied species together).27 In other words, they have no problem with the breed-species argument that Darwin articulated—recognizing that it extends only up to the level of family or order (p. 148, emphasis added).

Endnote #25 further elaborates on this statement:

Strictly speaking, the statement that “min appear to be best approximated by the classification level of family or order” applies only to those groups of creatures in which hybridization studies have been performed. Also, since the Bible never speaks of humans in terms of min, modern creationists do not apply the family/order rule to humans. (Also, humans cannot successfully breed with any other creature.) Nevertheless, since the results of these studies appear to be consistently arriving at the classification rank of family or order, and since this is true across several vertebrate classes, I have generalized the results (p. 297, emphasis added).

Endnote #27 also elaborates:

For invertebrates, plants, fungi, and microbes, the best taxonomic approximation for min is still uncertain, but probably above the level of species. At a minimum, modern creationists would have little problem endorsing the formation of new species within invertebrate, plant, fungal, and microbial genera or subgenera (p. 297, emphasis added).

Thus, it should be clear that the first formal discussion of min does not take a hard and fast stance that min is always (and only) equivalent to “family.”

In Chapter 10, I concur with this statement:

For example, though creationists and evolutionists disagree on ancestry above the level of family, they agree that vertebrate species within a family share a common ancestor (p. 248).

At first pass, a reader might wonder why did I not give the caveats about “family or order” in Chapter 10. However, as documented above, I already explained the details in Chapter 5. I assumed the reader would already have read the caveats in earlier chapters. Furthermore, the only datasets I used in Chapter 10 were datasets of species within families. Thus, for the purposes of Chapter 10, no caveat was needed.

Frello has tried to create a contradiction where none exists.

I do not conclude, as Jeanson will have it, that evolution at present can explain biogeography in all its details. I conclude that “Jeanson fails to account for biogeography . . . ”.

In spite of all Jeanson’s words, his position still necessarily is that Biogeography can be explained by migration out of Eurasia (Mt. Ararat), and mine that this is an unfounded position.

Again, as discussed above, Frello seems to be objecting to the fact that I didn’t write a chapter in Replacing Darwin that directly addressed the objection he wished to raise. In light of this fact, it’s hard to concur with Frello that “Jeanson fails to account for biogeography.”

Also, if Frello is insistent that we adjudicate a debate that Replacing Darwin touches hardly at all, why doesn’t he engage the points I raised in my previous response to him? Specifically, with respect to the modern debate and the many modern creationist hypotheses on biogeography, I challenged him with the following (Jeanson 2018):

If Frello wants to debate the question of biogeography in 2018, he’s going to have to design scientific tests that consider and eliminate each of these hypotheses [i.e., the hypotheses (described above) of common ancestry, historical contingency, biological function, competition among kinds, and differential extinction among kinds] before he can conclude that his evolutionary hypothesis is correct (p. 65).

Why does Frello not engage this? Why does he simply reassert his initial claims? Does Frello not have any scientific data from which to draw his assertions? If not, this reveals much about the deficiencies in his own position, and it says little about any potential deficiencies in mine.

Finally, Frello said earlier that “I think Jeanson’s statement ‘neither the creationist position nor the evolutionary model has a consistent, comprehensive, discipline-wide explanation for biogeography’ is fair. Nothing in my review talks against this view.” Here, he underscores that statement by admitting that evolution cannot “explain biogeography in all its details.”

In summary, Frello’s second round of statements on biogeography seems to have added little to his initial criticisms.

Frello: On “Frello’s Claims About Taxonomy”

This section contains at least two parts. I’ll respond with interspersed text, and then I’ll summarize where each part of the discussion is (see Summary of Subsection headings below).

Jeanson thinks I misrepresent his position, “. . . that both evolution and creationism predict hierarchies.” But how is that any different from my reference to Jeanson’s position being that: “. . . common descent is not needed to explain the nested hierarchies”?

Since English is not Frello’s first language, perhaps our disagreement is simply a misunderstanding. However, as I stated in our first exchange on Replacing Darwin:

I deliberately phrased my conclusions in this way because of my discussion of the method of inductive reasoning [also known as the hypothetico-deductive method] from Chapter 4. Furthermore, this distinction forms the basis for one of the major points of my book—points which Frello side-stepped . . . Frello’s misrepresentation is a significant foreshadowing of the direction of his arguments (p. 66).

I invite readers to review our previously published exchanges (Frello 2018a; Jeanson 2018) and judge for themselves.

Jeanson doubts that I will reject an often mentioned argument for evolution: The universal genetic code.1 Well Dr. Jeanson, I have news for you: I do reject it! That’s why I didn’t mention it in my review.

This is a remarkable concession. It places Frello’s position at odds with leading evolutionists of our day. For example, consider Futuyma’s and Kirkpatrick’s (2017) list of “Evidence for Evolution” (pp. 44–45). Under evidence #2 (Homology), the authors state, “the nearly universal, arbitrary genetic code makes sense only as a consequence of common ancestry.”

If Frello disagrees with leading evolutionists, what position on origins is Frello trying to defend?

Now that Jeanson has opened this discussion, let’s see where it leads. The common genetic code (the nuclear code) is an equally good argument for common design as for common ancestry, and therefore an argument for neither.

Well-stated. I’m pleased to see Frello concede this point. The failure of homology (whether genetic, anatomical, or embryological) to adjudicate the origins debate is one of the key points in Replacing Darwin.

It is in fact the mitochondrial genetic code, which can be used as an argument for common ancestry. Not because they are identical, but because they are different. Mammals have one code, Insects a slightly different one, Fungi yet another. More than ten slightly different codes are known at present. Why would a designer use different codes in different organisms, and why would the differences follow groups of organisms, otherwise accepted to be closely related? From an evolutionary point of view, this is easy to understand. The mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) has only very few protein coding genes (13 in most animals). Therefore a code-changing mutation has a much better chance of not being lethal here than in most other genomes. A code-changing mutation in the nuclear genome (with tens of thousands of genes) would be lethal, because it would change the amino acid sequence of so many vital genes that at least some are bound to have their function destroyed.

Here Frello gives a qualitative rather than a quantitative, explanation for why—from an evolutionary perspective—multiple genetic codes exist. I wonder how a person could falsify such an explanation. In fact, I wonder how evolutionists like Frello can cite the diversity of genetic codes as evidence for evolution, yet evolutionists like Futuyma can cite the unity of genetic codes as evidence for evolution.

If Frello can employ this logic, then so can I. “Common design” explains why a common genetic code exists. It also explains why a mitochondrial code is common across mammal kinds. It explains why a mitochondrial code is common across insect kinds. It explains why a mitochondrial code is common across fungi kinds. And so on.

More realistically, and in more precise scientific terms, I can derive a testable prediction from the observations of mitochondrial codes that Frello cites above. From a creationist perspective, these various mitochondrial codes possess the similarities and differences that they do in order to fulfill purposes that track with the level of similarities and differences among the codes. In other words, these code differences exist for functional reasons. This is something that we can test in the lab. We should be able to swap codes (nuclear for mitochondria, mammal for insect, etc.) and examine the effect on the function of the organism. (To be sure, these are by no means simple, inexpensive experiments. Nonetheless, these experiments are the way forward in testing the expectations of my model.)

Does Frello’s explanation make any such predictions on the function of these codes? Or is it simply an arbitrary post-hoc explanation without any falsifiable predictions? If so, then it is not a scientific explanation, by definition.

In my view, our fundamental disagreement is the following: What does it take for a taxonomy to be more than an arbitrary personal opinion.

(Just a clarifying comment for myself and for the reader: It looks like Frello is now switching to a different topic—leaving the subject of mitochondrial DNA codes and going on to the subject of general taxonomy. The following paragraphs all revolve around the question of whether taxonomy is arbitrary or not.)

Evolution suggests one, and only one, foundation for taxonomy: Common descent.

Actually, evolution suggests two foundations: common descent and diversification (i.e., speciation)—which leads to explanations like convergent evolution, which by definition admits that certain data do not fit a strict common descent and diversification model. See our previously published exchanges (Frello 2018a; Jeanson 2018).

Accuracy aside, why should the expectations of evolution be the chosen foundation for taxonomy? For the foundation for taxonomy, what makes Frello’s choice of conformity to evolutionary ideas about common descent a rational choice rather than an arbitrary one?

YEC (Or more precisely: the idea that living organisms are designed, and groups of organisms above the level of “created kinds” therefore are genetically unrelated) cannot suggest any such unique foundation for taxonomy.

It’s unclear what Frello means by unique. Almost by definition, creationist explanations for taxonomy will be unique because they will be different from the explanations offered by >97% of the mainstream scientific community.

From the discussion below, perhaps Frello is using unique as synonymous with nonarbitrary. If so, and if we grant (for sake of argument) the point that a creationist argument is arbitrary, why should it be rejected? Frello thinks it should be rejected and replaced—with an evolution-based taxonomy that Frello arbitrarily thinks should be the foundation of taxonomy. If this is Frello’s argument, it is not a logically rational one.

Alternatively, Frello might be using unique as synonymous with single—which, if so, would be inaccurate because evolution invokes at least two elements (common descent and diversification/speciation) in its explanation for taxonomy.

Jeanson tries to do so for designed objects, vehicles. He suggests that vehicles should be placed in two large groups: powered vs. non-powered. But he cannot, and does not, offer any explanation to why this should be a better criterion than any other.

Who gets to decide what is a “better” criterion than another? And how does such a person get to do so without resorting to circular reasoning? (Frello seems to resort to circularity—see below.) Frello is making very large assumptions about “inferior” and “better”—but without any logical justification. Why should we use Frello’s criteria for “better” rather than someone else’s? Frello seems to be making a very arbitrary argument—his own personal opinion—in his attempt to show that my classification is arbitrary and a matter of my own personal opinion.

In Frello 2018, I mention military vs. civilian; for transportation of persons vs. for transportation of goods as examples of alternative criterion. Another suggestion could be by brand. Why even group vehicles together? Why not all powered, designed objects vs. non-powered objects? Anything goes. None are natural, all are cultural.

Who gets to decide what grouping is “natural”? What makes something natural rather than cultural? Even if Frello provides definitions for these terms, why should classifications be natural, as Frello seems to imply? What logical justification can Frello give for this part of his argument? Currently, it seems that Frello is simply asserting his own standard (opinion) of natural—without justifying why it would be natural to use his standard.

Common descent immediately suggests that we should look for a nested hierarchy of groups-within-groups of organisms.

Except when it doesn’t. To reiterate a point we covered in our previous exchange (Jeanson 2018):

Anytime the evolutionary model invokes “convergent evolution,” it is implicitly acknowledging a biological part or feature that does not follow the expected (“reasonable”) taxonomy. For instance, despite the obvious outward similarity, marsupial moles and placental moles are not classified together. Instead, marsupial moles group with creatures like kangaroos, and placental moles group with creatures like llamas. As another illustration, despite their outward resemblance, echidnas and hedgehogs belong to very different taxonomic categories. Based on their modes of reproduction, echidnas group with the platypus, and hedgehogs group with elephants (p. 66).

In other words, evolutionists claims that marsupial moles and placental moles look similar, not because of common descent, but because of “convergent evolution.” “Convergent evolution” is the explanation that evolution invokes to make non-nested-hierarchies compatible with the expectation of nested hierarchies based on common descent and diversification/speciation.

Talking about multicellular organisms, there can be only one such correct hierarchy: The one that reflects common descent (at least above the genus level, where hybridization becomes very implausible).

If Frello’s statement treats the word “correct” as “consistent with evolution,” then his sentence represents a statement on the expectations of evolution. If, instead, he means “correct” as “conforming to reality,” then Frello has engaged in circular reasoning. See below for evidence that the latter might be in view.

Even if we accept Jeanson’s arbitrary suggestion of powered vs. non-powered vehicles; we still do not have a unique system beneath this level. If powered defines a group, it seems reasonable that the type of engine should define the next, lower, level. But Jeanson suggests land vs. air vs. sea instead. This choice again is completely arbitrary.

For sake of argument, let’s grant Frello his point. How does he intend to make taxonomy non-arbitrary? By arbitrarily asserting that evolution must be the foundation? If so, then this is circular reasoning.

In biology, as a consequence of common descent, the science of taxonomy therefore becomes the science of identification of the nested hierarchy of groups of organism. From this, it follows that one kind of information beats all others, when it comes to identification of such groups: DNA. It is easy to see why: groups are defined by common ancestry. Ancestry is equal to genetic ancestry. Genetic information is stored in DNA.

Frello has now revealed the circular nature of his entire criticism against my taxonomic claims. “As a consequence of common descent, the science of taxonomy therefore becomes the science of identification of the nested hierarchy of groups of organism”—yet common descent (which Frello is equating to universal common descent) is the very point in question. He and I are debating whether the nested hierarchical pattern of life points toward design or toward evolution. To invoke evolution as the explanation for why evolution is correct, is to reason in a circle.

In YEC, taxonomy becomes the arbitrary choice of groups. Arbitrary at all levels. Based on an equally arbitrary choice of traits. If this is what Jeanson thinks qualifies as a scientific argument in favor of a taxonomy for designed objects, it is no wonder that creationism is completely ignored by mainstream scientists as irrelevant.

To point it out more unambiguous: whenever possible, DNA should be (and is) used for identification of groups.

Again, Frello’s insistence that “Whenever possible, DNA should be (and is) used for identification of groups” is based on his insistence that evolution is true. This, again, is reasoning in a circle.

Not fur-color or -structure, not reproductive organs, not general appearance or any other physiological or anatomical trait. Dealing with groups where DNA is not available (especially fossils), physical traits have to be used.

Why? What logical justification does Frello give for this rule—other than his own personal opinion?

Again, a guiding principle can be found: traits that are difficult to change without disrupting survival or reproduction, should be preferred.

Why? What makes Frello’s assertion anything but his own personal opinion—or the consequence of circular reasoning?

Jeanson goes to some length ridiculing the identification of such traits, all in vain.

How does Frello’s current attempted justification help his argument? How is it anything but his own personal opinion?

Jeanson thinks I concede that not all genes suggest the same phylogeny. I simply state a fact.

I appreciate Frello reiterating this concession.

As Jeanson knows, contradicting phylogenies are mostly found between closely related species, and can be understood as “incomplete lineage sorting” or as the result of the stochastic nature of mutations. Using large groups of genes solve this problem.

By citing the solutions to the problem of contradicting phylogenies, Frello admits critical flaws in the method that he holds up as the gold standard. This further weakens his criticism.

All in all, if all living organisms evolved from a common ancestor, we should expect to be able to group living organisms according to one natural criterion: common ancestry, based on genetics as the most reliable source of information.

Again, evolution invokes two elements in taxonomy—common ancestry and diversification/speciation.

If living organisms were designed, no such natural criterion or basic source of information should be expected to be found.

Why not? Frello again appears to be attempting to win an argument by assertion rather than by evidence and rational arguments.

Judge for yourself.

On this point, I heartily agree with Frello. I especially encourage the reader to examine the logical coherence of Frello’s claims.

Summary of Subsection

In Replacing Darwin, I make the argument that both evolution and creation predict the existence of nested hierarchies in nature. Evolution derives this prediction from the nature of their evolutionary processes of common ancestry and diversification. I derive predictions for creation via analogy to the design world.

In this exchange, Frello has tried to undercut my claim that the design world contains nested hierarchies. His main argument is that nested hierarchies in the design world are completely arbitrary and, therefore, not relevant to the nested hierarchies in nature, which Frello thinks are unambiguous, non-arbitrary, and natural. However, Frello’s justification for the unambiguous, non-arbitrary, and natural properties of the nested hierarchies in nature all derive from the assumption of evolution. This is a circular argument and not a valid objection.

In reality, the nested hierarchies in nature and in the design world are parallel. Let’s reflect on the elements of this discussion that are unambiguous, and then separate them from the elements that are arbitrary personal choices. On the one hand, the existence of nested hierarchies (in biology and in the design realm) is an unambiguous fact. Mathematically, when all the various characteristics of species (or designed things) are enumerated and compared one-by-one, a nested hierarchy emerges. This result is clear and unequivocal.

On the other hand, converting these nested hierarchies into a system of taxonomy involves a significant amount of arbitrary personal choice. For example, to say that mathematical patterns should dictate one’s taxonomy is itself a product of an arbitrary decision to use mathematical optimization as the final criteria. As another illustration, to say that only DNA-based (or blueprint-based) nested hierarchies should form the basis of taxonomy, is also an arbitrary choice.

Thus, the nested hierarchies and taxonomies in nature and in the design world are parallel. Frello fails to engage this bigger point.

Jeanson thinks that the reason I do not comment on transitional forms, homologous structures, or vestigial structures is that I agree with his arguments.

Actually, I say the following (Jeanson 2018):

I find it revealing that Frello had nothing to say about the other points I raised in Chapter 5. For example, I pointed out that both evolution and design predict the existence of so-called “transitional forms” and of “homologous” structures. Scientifically, this means that the existence of “transitional forms” and of “homologous” structures cannot be used as evidence for evolution over against design. I also pointed out the deficiency of anti-design arguments from “vestigial” structures and organs . . . Since Frello had nothing to say about any of these arguments from Chapter 5, I assume he concedes them. Given the prominent role that “transitional forms,” “homologous” structures, and anti-design arguments typically play in origins debates, this is remarkable (p. 67).

In other words, since Frello had written a strongly-worded denunciation and critique of Replacing Darwin, I assumed that he would attempt to rationally engage my points, as well as my challenges to evolution—especially my challenges to textbook evolutionary arguments. By ignoring my challenges in his first review, I highlighted for the reader that Frello had no answer.

It appears that Frello now wishes to break his silence and I welcome this change.

Let me immediately free him from his delusion.

Rather than being a delusion, it’s a simple observation of Frello’s silence.

Regarding transitional forms. Why would a designer construct several transitional forms between a land animal and a whale (e.g. in terms of hind legs and the position of nostrils), just to see them go extinct within a few thousand years from their creation, and for no obvious reason? I guess I need not explain why transitional forms are expected, if we accept evolution.

This is a very intriguing response. Essentially, Frello side steps the science of transitional forms and goes into a non sequitur argument about extinction. In addition, Frello’s problem with extinction isn’t scientific at all; it’s theological. Since we’re on the topic of theology, and since Replacing Darwin is primarily concerned with science, rather than theology, I refer the reader to my other published work1 (which Frello fails to engage) that deals with the theology of extinction (in particular, see the section titled “The Theology of Mammalian Extinction”).

Regarding homologous structures. I do not recall reading about that in the book. The search engine (I have the Kindle-version of the book) doesn’t find the term. Perhaps Jeanson talks about it under a different term.

This is a helpful admission on Frello’s part. To recap the relevant context in Replacing Darwin: Chapter 5 (The Riddle of Ancestry) covers the classic, non-genetic arguments for evolutionary common ancestry. For example, on pages 128–130, I discuss the relationship of evolution to (1) the nested hierarchical pattern of life and to (2) the existence of species that “blend the features” of two very different species. Then, on pages 132–134, I review the classic evolutionary arguments from homology. In fact, Figure 5.3 (“Shared forelimb structure across diverse species,” p. 132) and Figure 5.4 (“Development stages of vertebrate species,” p. 133) are near facsimiles of standard textbook illustrations of homology. Furthermore, if Frello was familiar with Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, Frello should immediately recognize Figure 5.3, based on Darwin’s own statements:

What can be more curious than that the hand of a man, formed for grasping, that of a mole for digging, the leg of the horse, the paddle of the porpoise, and the wing of the bat, should all be constructed on the same pattern, and should include the same bones, in the same relative positions? (Darwin 1859, 434).

How could Frello have missed my discussion of homology? Is Frello critiquing a book that he has only skimmed?

Regarding vestigial structures. First we have to agree upon what that means. According to NatureEducation2, vestigial describes “. . . something occurring in a simpler, less functional state; sometimes a remnant of a larger more robust form” It clearly does not mean “purposeless leftovers of evolution” as Jeanson has it in his book. This nullifies Jenson’s arguments.

I’m having trouble following Frello’s argument. He takes exception to my definition, yet supplies one remarkably similar to the one I used. I say “purposeless”; he says “simpler, less functional.” I say “leftovers of evolution”; he says “a remnant of a larger more robust form.” Somehow, his definition “nullifies” my argument?

More likely, Frello appears to be engaging in and repeating a practice that I already covered and challenged in my book. The evolutionary practice is best seen in a historical light. First, let’s begin with the language Darwin used to describe “rudimentary,” “atrophied,” and “aborted” organs:

I have now given the leading facts with respect to rudimentary organs. In reflecting on them, every one must be struck with astonishment: for the same reasoning power which tells us plainly that most parts and organs are exquisitely adapted for certain purposes, tells us with equal plainness that these rudimentary or atrophied organs, are imperfect and useless (Darwin, 1859, p. 453).

With respect to these organs, Darwin called them useless—and the immediate context for his statement is the realm of design principles, a realm which is intensely concerned with ideas such as purpose and function. I think purposeless is about as close a synonym to useless as one can get. In light of this fact, how can Frello rationally take exception to my term?

Second, let’s review how evolutionists have expanded their definition of vestigial. Why would evolutionists do so? Because many useless organs were eventually shown to be functional. I cover several examples in Replacing Darwin. I also cover the evolutionary response to this fact. For example:

In some cases, when the argument for non-function can no longer be sustained in the face of new research, evolutionists have emphasized a different element of the anti-design argument. In other words, rather than point to non-function as evidence of bad design, they have emphasized certain elements of the biology that seem to harken more to evolution than to any other explanation. For example, evolutionist Jerry Coyne concedes that the human appendix is functional. But he claims that the size of the human appendix matches the expectations of evolution. As our evolutionary ancestors evolved from an herbivorous diet in the trees to a more carnivorous diet on land, Coyne claims that our appendix size would have changed consistent with this dietary progress.

Recent studies have shown that there is little correlation among mammals between diet and appendix size. Coyne’s counter-explanation has been effectively rendered invalid (p. 143).

Is Frello trying to re-employ Coyne’s strategy?

More importantly, why does Frello still avoid directly engaging my arguments against the leading, mainstream evidences for evolution?

Summary of Subsection

In our first exchange, I highlighted that Frello had nothing to say about my challenges to the textbook evidences for evolution from the fossil record, from homology, and from vestigial organs. In this exchange, Frello continues his silence—by side stepping the scientific discussion of transitional forms and changing the subject to theology, by admitting he had no idea that I discussed homology in Replacing Darwin; and by quibbling over terms used to describe vestigial organs, which suggested he was unfamiliar with this section of Replacing Darwin as well. This is a remarkable sequence of events on topics that are central to the debate over the origin of species.

Frello: On “Frello’s Claims About Genetic Diversity”

I have to admit that Jeanson is right in his criticism that my treatment of this topic is less than rigorous, and that I tend to confuse the information given in Chapters 7–10.

This is a helpful concession, and it has the potential to advance our discussion.

So let me try to clear out the points on which Jeanson thinks I am ambiguous or misrepresenting him.

First, let me clarify my use of the term homology. As Jeanson assumes I mean “percent relative genetic identity.” The alternative being absolute instead of relative.

This clarification makes our exchange all the more efficient. Thank you.

One of Jeanson’s conclusions in Chapter 8 is that most variations in nuclear DNA, found in organisms that share a common ancestor, are inherited from variation in that common ancestor. The logic of the analyses in Chapter 10 is that all the variation in mtDNA, found in organisms that share a common ancestor, are due to mutations. I agree on both points. That is an uncontroversial position from an evolutionary point of view.

This is a helpful summary of Frello’s view vis-à-vis mine.

mtDNA tells an unambiguous story. As stated above, Jeanson accepts that homology in mtDNA can be used as a measure of the distance to a common ancestor.

Here, Frello’s argument departs from its good beginning. Despite clarifying his use of terms, Frello fails to correctly apply his terms to my position. His attempt to restate my view is incorrect—and a repetition of an error that Frello made in our first exchange. For clarity, I’ll repeat what I said in our last discussion (Jeanson 2018):

Do I assume that percent relative genetic identity reveals genealogical relationships [i.e., distance to a common ancestor]? No. In fact, I argue for the opposite conclusion. In Chapter 5, I deal with the question of whether the fact of nested hierarchies (percent relative genetic identity is a form of nested hierarchy) is automatically evidence of common ancestry. (Evolutionists believe this is so.) By revealing that the design model also predicts the fact of nested hierarchies, I show (scientifically) that nested hierarchies are agnostic on the question of common ancestry. Because the competing hypothesis (design) cannot be eliminated by the fact of nested hierarchies, nested hierarchies say nothing about common ancestry. In Chapters 7 and 8, I extend this logic to the realm of genetics—specifically, to the realm of mtDNA (Chapter 7) and the realm of nuclear DNA (Chapter 8). In other words, in Replacing Darwin, I argue that the fact of percent relative genetic identity does not reveal genealogical relationships because two competing (and opposite) hypotheses predict the existence of percent relative genetic identity.

Frello has begun his claim with an assertion that has the logic of Replacing Darwin completely backwards (p. 69).

To reiterate: I do not accept that homology—percent relative genetic identity—can be “used as a measure of the distance to a common ancestor.” Instead, I show that percent relative genetic identity fails to distinguish between the hypotheses of design and of common ancestry.

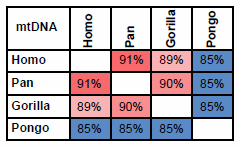

If mtDNA from Humans, Chimps, Gorillas and Orangutans are compared, the pattern is clear.

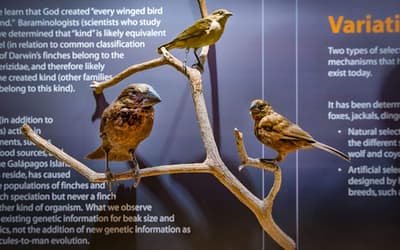

Fig. 1. Percent identity between mtDNA from Humans (Homo); Chimpanzees and Bonobos (Pan); Western and Eastern Gorillas (Gorilla) and Bornean and Sumatran Orangutans (Pongo). Colors indicate level of homology: Red: high; Blue: low.

I agree—the percent relative genetic identity is clear. However, I do not accept that homology— percent relative genetic identity—can be “used as a measure of the distance to a common ancestor.”

Jeanson accepts the relationship between Chimpanzees, Gorillas and Orangutans, identifying them as members of the family Pongidae, (which is no longer accepted in mainstream taxonomy).

It’s not currently accepted in mainstream taxonomy because mainstream taxonomy for chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, and humans is based on evolution—the very point in question.

But from a genetic point of view, it is unfounded to accept the relationship between these three genera, leaving out humans.

Why? I’ve already made it clear that I explicitly reject percent relative genetic identity as a means to identify common ancestors or kinds. What basis, then, do I invoke for the common ancestry of chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans? To reiterate my quote above:

Strictly speaking, the statement that “min appear to be best approximated by the classification level of family or order” applies only to those groups of creatures in which hybridization studies have been performed. Also, since the Bible never speaks of humans in terms of min, modern creationists do not apply the family/order rule to humans. (Also, humans cannot successfully breed with any other creature.) Nevertheless, since the results of these studies appear to be consistently arriving at the classification rank of family or order, and since this is true across several vertebrate classes, I have generalized the results (p. 297, emphasis added).

The only reason he does so, is the YEC assumption that the Bible is infallible (as mentioned, scientists would never accept any text as infallible).

This is incorrect, and a misrepresentation of my position. See above.

As indicated in fig. 1, mtDNA strongly suggests that Chimpanzees are closer related to Humans than to Gorillas or Orangutans.

This continues the misrepresentation of my book. See discussion above.

Jeanson accepts that genetic homology can be used to indicate relationship within kinds, but apparently not in this case!

Again, a straw man argument. I do not accept that genetic homology—percent relative genetic identity—can be used to indicate relationship within kinds. See above.

Actually there is no clear demarcation between within kind and between kinds when it comes to genetic homology.

Correct—because I do not accept that genetic homology—percent relative genetic identity—can be used to indicate relationship within kinds. See above.

I’ll return to this in the section on speciation.

I will engage his further comments there.

To summarize this section, Frello’s entire criticism is based on a straw man of my position. This is not a rational way to engage the science in Replacing Darwin.

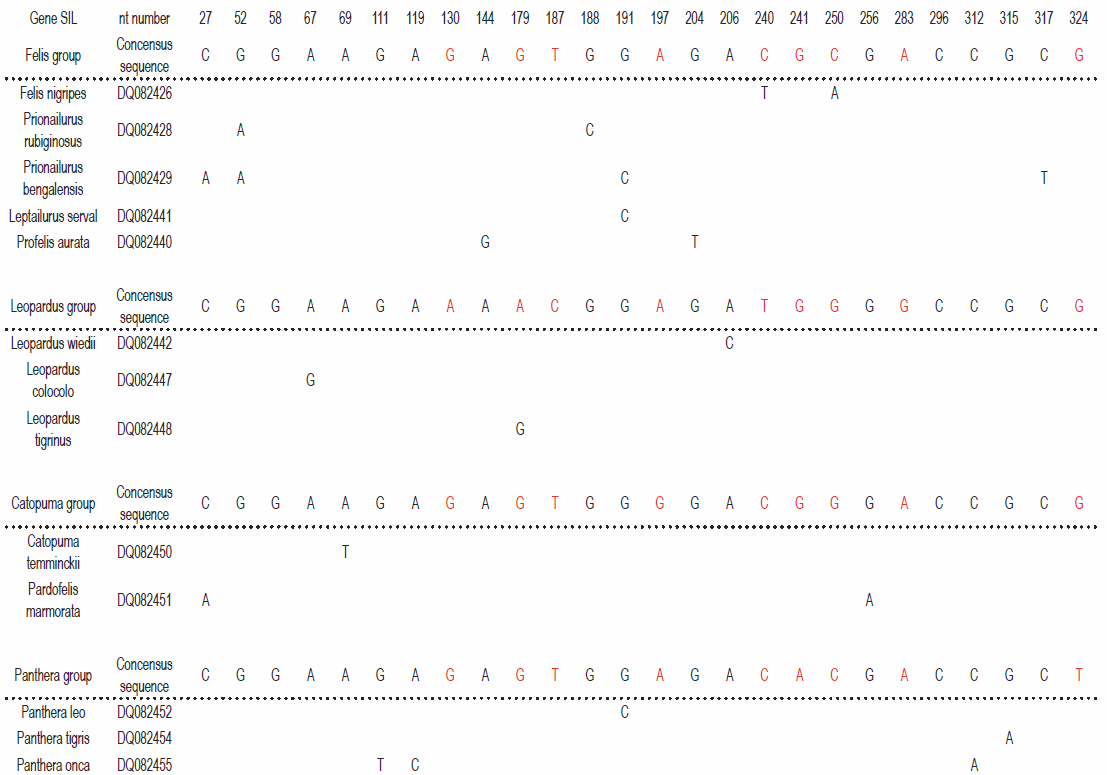

Jeanson has some partly relevant comments on fig. 1 in Frello 2018. (Mutations accumulated since the Flood in various species of the Cat-family, Felidae, Johnson et al. 2006.)

(A clarifying comment for myself and for the reader: Frello appears to be leaving the genetic homology discussion and switching to a new topic.)

To explain this I first have to explain a little genetics. According to NatureEducation,2 the term allele refers to an alternative form of a gene not alternative single nucleotides, as Jeanson will have it.

Here, Frello begins his argument with logical misstep. Rather than challenge my argument on its own terms, Frello arbitrarily insists that we adopt his definition (the definition from NatureEducation) to evaluate my claims. This immediately renders his argument a straw man.

For the sake of clarity, let’s call alternative forms of a gene, gene-alleles, and alternative single nucleotides, nt-alleles. Each individual has two copies of each gene. From a YEC point of view, all Cats descent from two individuals onboard the Ark. Together these two individuals therefore had a maximum of four different copies, gene-alleles, of each gene.

Again, this is a straw man. (See justification and explanation below.)

The problem is then to identify groups of species with genes, which descend from the same gene-allele. Differences within such gene-alleles must be due to mutations that have occurred since the Flood.

Again, a straw man. (See justification and explanation below.)

Jeanson’s point is now that there can be a multitude of differences in the DNA-sequence of two gene-alleles. This is absolutely correct, and I have not argued against it. What I have done in fig. 1 in Frello 2018 is to add the differences between species of Cats for 15 different genes, and identify four groups of most identical species; each supposedly representing the descendants of one original gene-allele per gene.

Again, a straw man. (See justification and explanation below.)

By doing so, I risk mixing number of differences within gene-alleles (which is relevant), with number of differences between gene-alleles (which is not relevant). It is not clear from Jeanson 2018 that this is what he thinks is wrong with my calculations, but it is the only way I can make sense of his objections.

Actually, I make it quite clear in our first exchange that his argument (repeated in this exchange) is a straw man (Jeanson 2018):

[I]n one of my published papers (Jeanson and Lisle 2016) that I refer to at least 15 times in Replacing Darwin, I explicitly addressed Frello’s error:

If an allele is defined in terms of a gene unit, then generating “allelic” diversity by mutating just one gene per mutational event produces little diversity. Instead, if an allele is defined as a single genomic position, independent of its relationship to a gene, then enormous allelic diversity can be generated by mutation . . . As an aside, allelic diversity need not arise via mutation. Again, if we use the genomic position definition of an allele rather than the gene unit definition, other mechanisms besides mutation can generate allelic diversity. For example, a single gene typically spans thousands of nucleotides, and SNVs [SNVs = Single Nucleotide Variants] might be distributed throughout the gene—for example, at 90 of the nucleotides within the gene. If we allow for the genomic position definition of alleles, every single one of these 90 SNVs may have existed in a heterozygous state in each of the individuals of the pairs brought on board the Ark.

Expanding this single gene example across the entire genome reveals a tremendous potential for allelic diversity on the Ark. In just two diploid individuals, four genome copies exist. Since only four DNA base-pairs exist, virtually every possible genomic position allele (i.e., far more than 4–28 gene unit alleles) could have been present at the time of the Flood, if the individuals were heterozygous (Jeanson and Lisle 2016, 99) [emphasis in original paper].

In other words, every single one of the nuclear DNA differences in Frello’s graph could have existed in a heterozygous state in the felid ancestor on board the Ark—because my model defines alleles in terms of DNA position, not individual genes. Thus, Frello’s (apparent) claim—that a maximum of four versions of each gene could be present in this original pair—is incorrect.

Conversely, my model has no need for the mutation rates that Frello claims; in fact, in theory, it has no need for mutations in this example at all (pp. 69–70).

Jeanson is correct that this gives a wrong picture,

I don’t think Frello grasps why his position is a straw man, despite this statement. See below for an example of why I think the point is still lost on him.

and I have therefore attacked the problem in another, more correct, way, looking at single genes. Fig. 2 shows the variable positions in the gene SIL. The results clearly show that a considerable number of mutations is necessary to explain the pattern of sequence variation.

Once again, Frello is straw-manning my position by defining created diversity in terms of gene units, rather than in units of DNA position.

A total of 22 mutations is found (not taking selection into consideration). The largest number of mutations in a single group is 11. If the mutation rate in Cats are comparable to that of Humans, the probability of finding this number of mutations in this dataset is negligible.4 Therefore, the conclusion is still correct: Jeanson’s suggestion: that present day variation among species is due to the distribution of different original gene-alleles, cannot explain the variation among modern species.

Once again, Frello is straw-manning my position by defining the created diversity in terms of gene units, rather than units of DNA position.

Of course, a single example is not proof, though in this case it is a very strong indication. I therefore invite Jeanson (or any of our readers) to repeat the analyses for the rest of the genes in Johnson et al. 20065 or in any other nuclear gene, sequenced in several closely related species. (Kinds that, according to YEC, were either not in the Ark (e.g. aquatic Mammals) or were present in more than one couple (e.g. Bovidae) cannot be used in such analyses).

I also invite readers to do their own analysis. But I would encourage them to do it in a manner that deals with my actual claims, rather than Frello’s caricature of my claims.

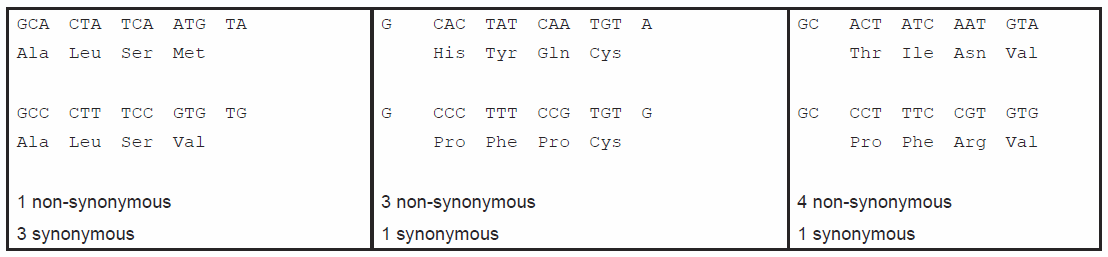

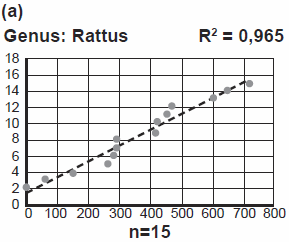

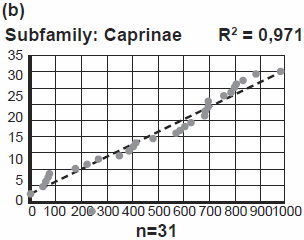

Fig. 2. YEC-interpretation of 12 copies of a partial sequence of the SIL-gene from species in the Cat-family, Felidae. Only variable nucleotides are shown. The four gene-alleles are indicated as the four groups (identified to be the combination of sequences that result in lowest number of deviations from the consensus of each gene-allele). In each group, a consensus sequence is identified as the one that results in the lowest assumed number of mutations. Differences between the four consensus sequences are indicated in red. Only those nucleotides that deviate from the relevant consensus sequence are indicated. Deviations that might originate from a single mutation are in boxes. Only species with unique deviations from the relevant consensus sequence are shown (12 out of an original set of 38 species). To explain the results the following minimum numbers of mutations are necessary: Felis group: 11. Leopardus group: 3. Catopuma group: 3. Panthera group: 5.

Frello: On “Multifunctionality of Mitochondrial Genes”

The first part of this section becomes somewhat convoluted. I’ll respond with interspersed text, and then I’ll summarize where the discussion is (see “Summary of Subsection” below).

Just to make sure that our reader knows what we are talking about, most animal mitochondrial genomes (mtDNAs) contain 13 protein-coding genes, 2 rRNA-coding genes, 20+ tRNA coding-genes, and the so-called control region or D-Loop. The mitochondrial protein coding genes deal with some of the most fundamental biochemistry in the organisms. Genes with the same biochemical functions (and most often with recognizable amino acid sequence) are found throughout not only the animal kingdom, but in plants, fungi, and the plethora of unicellular Eukaryotes. Even in bacteria.

Jeanson quotes his 2013 article, where he accepts that the hierarchy suggested by mtDNA homology reflects the one suggested by the Linnaean classification system.

Just to make sure we’re on the same page, here’s what my paper (Jeanson 2013) actually says (it’s not quite as strong as Frello implies):

These results [from earlier in the paper] also implied that the modern mitochondrial sequence differences among “kinds” represented functional differences . . .

What function might these individual differences perform? Several functional hypotheses could be invoked to explain the clustering patterns observed in the mitochondrial protein sequences. However, since the clusters of high percent identity seemed to correlate with taxonomic rank above the level of family (Figs. 2–14), I explored whether taxonomic rank would precisely predict the clusters that formed. If taxonomic rank did precisely identify the clusters which naturally formed, this result would imply a taxon-specific function for these amino acid differences.

Toward this end, I created a predictive, heat-mapped template based on the four higher-level Linnaean taxonomic categories [kingdom, phylum, class, order (no intermediate categories between them)] (Fig. 15). I based my template on the species with an ATP synthase subunit 6 (“ATP6”) entry, since the number of species (2697) with an ATP6 protein was close to the total number downloaded species/entries, 2704.

This artificial taxonomic template (Fig. 15) clearly identified some of the clustering patterns I observed for the mitochondrial protein sequence alignments (R2 value between Fig. 2 and Fig. 15 is equal to 0.79). For example, the template identified the Arthropoda and vertebrate clusters, as well as the Actinopterygii, Aves, Mammalia, and Testudines clusters (compare Fig. 15 to Figs. 2–14). The template also isolated some of the major phyla, such as Cnidaria, Echinodermata, Nematoda, and Porifera (Fig. 15). However, the template did not identify all the clusters observable in the protein alignment results, such as the sub-cluster within vertebrates (including the classes Actinopterygii, Aves, Amphibia, and Mammalia, and members [Squamata, Testudines] of the former class Reptilia). It also failed to identify the clustering that occurred among Cnidaria and Porifera (compare Fig. 2 to Fig. 15). Thus, the overlap between the taxon-based heat map and protein sequence-based heat map indicated that taxonomic rank and grouping partially explained the clusters but did not explain all the mitochondrial protein sequence patterns (pp. 489–491, emphasis added).

Thus, I observed that the hierarchy partially matches the one suggested by the Linnaean classification system.

He then states that this system is based on function. I assume he is mainly talking about anatomical and physiological function, as Linné hardly knew any biochemistry.

As the quote above demonstrates, the connection to Linnaeus was a partial match—and one that happened to have a fairly strong correlation coefficient. But it’s not the only hypothesis or potential explanation.

His conclusion is to ascribe such function to the genes of mtDNA.

Again, I observed that the hierarchy partially matches the one suggested by the Linnaean classification system. Thus, my conclusion is to partially ascribe such (anatomical and physiological) function to the amino acid differences of mitochondrial proteins.

Just to clarify, evolutionary theory offers a much simpler explanation: homology is due to common descent at all levels.

Actually, according to evolution, homology (defined as “percent relative genetic identity” above, assuming Frello is still using this definition) reflects common ancestry and diversification/speciation, which leads to instances of convergent evolution.

Clarification aside, Frello’s contrast is something of a non-sequitur. The creationist position is that percent relative genetic identity is a product both of the initial creation act and of mutations since creation. This explanation leads to testable predictions on function. Frello contrasts this creationist prediction of function with the evolutionary position on percent relative genetic identity—but without giving any testable predictions on function. What is Frello trying to prove?

Jeanson then argues that he does not necessarily suggest multiple anatomic/physiological functions of each gene. Instead, optimization6 of the known function in the various organismal contexts could be relevant.

Again, as my published material clearly shows, anatomic/physiological functions are one of many potential functions. Furthermore, the original context (Jeanson 2013) for my statement on optimization reveals that it, too, was one of many hypotheses:

Several hypotheses can be proposed to explain the involvement of mitochondrial proteins with taxon-specific traits. For example, modern protein sequences might still perform the same basal metabolic function traditionally ascribed to them (i.e., participation in the electron transport chain), but the sequence might be optimized metabolically for the specific organismal context in which each protein is found.

Alternatively, each protein might be connected in a genetic network to pathways specifying taxon-specific traits (Lynch, May, and Wagner 2011). The phenomenon of protein “moonlighting” (Jeffery 2003) raises the possibility that the traditional metabolic functions of each mitochondrial protein are just one of many functions for each protein. For example, the electron transport chain protein cytochrome b (“CYTB”) might participate, not just in basal energy transformation, but also in DNA transcription as a transcription factor, similar to the findings for the glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (“GAPDH”) (Kim and Dang 2005) (p. 496, emphasis added).

I agree that optimization is a very likely scenario.

What testable predictions follow from Frello’s position?

However, he makes no argument, as to why such optimization should reflect the same hierarchies, regardless of what gene you are looking at.

This is factually incorrect; see below for justification.

And why should it be the same hierarchy suggested by anatomy/physiology?

For a mechanistic explanation, see below (which quotes from my reply to our last exchange).

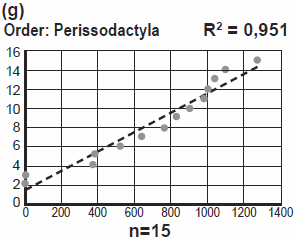

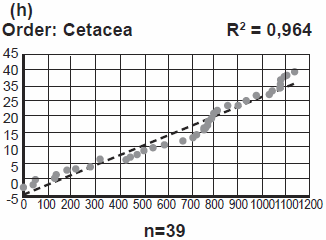

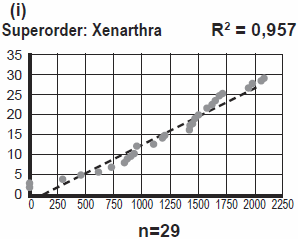

Jeanson makes no attempt, neither in this response, nor anywhere else to my knowledge, to explain why mtDNA from Horses, Tapirs, and Rhinos (order: Perissodactyla) should be more identical to each other, than mtDNA from, say, Horse and Cow, or Rhino and Elephant, if the only function refers to optimization.

This is also factually incorrect; see below for justification.

What kind of relevant optimization could result in this striking pattern?

To correct Frello’s misrepresentation and (again) answer his challenge, here is what I actually said (Jeanson 2018):

When organisms are built during development, genes control this process. Furthermore, this process can be described, not in three dimensions, but in four—the three spatial dimensions, and the time dimension. Since proteins are molecules, and since the cell represents an enormous space relative to the size of molecules, the number of possible places for genes to act exceeds our comprehension. Furthermore, since genes tend to act at sub-second speeds, and since even rapidly-developing creatures like Caenorhabditis elegans still require hundreds of thousands of seconds to develop (humans require tens of millions of seconds), the number of possible times for genes to act exceeds our best comprehension. (The times and places at which a gene—or a gene product—acts represent some of the seminal parameters delineating a gene’s function.) If we expand our exploration to consider all the physical and temporal ways we can combine the actions of genes, the number of possible permutations becomes nearly impossible to count. The potential functional space to be explored likely exceeds the actual functions that cellular molecules realize. Furthermore, these functions are surely determined—at least in part—via the sequences of the genes themselves. Thus, (1) using mitochondrial sequences to create a nested hierarchical taxonomy, while simultaneously (2) finding distinguishing molecular functions for these same sequences is straightforward. The functions for these sequences might not yet be discovered. But Frello’s theoretical objections pose no real hurdles to my hypothesis (p. 73).

Thus, Frello is incorrect. I actually make a very straightforward argument as to why the functionally-significant gene sequences should reflect the same hierarchies, regardless of what gene you are looking at, and why they should be the same hierarchy suggested by anatomy/physiology, and why mtDNA from Horses, Tapirs, and Rhinos (order: Perissodactyla) should be more identical to each other, than mtDNA from, say, Horse and Cow, or Rhino and Elephant. The explanation? The complexity of gene expression. The logic is simple: Gene expression defines traits (via the process of development); traits define taxonomy. Therefore, genes in mtDNA are expected to reflect taxonomy.

In fact, the complexity gene expression allows for so many mathematical combinations that it is sufficient to account for each of these phenomenon. Frello does not appear to have engaged my arguments.

He then goes on to the kind of function I was referring to—anatomically and physiologically relevant function. To my great (admitted, malicious) pleasure, he cites his own suggestion (Jeanson 2013), that the ATP6-gene could have some function in egg laying. This is, pardon my French—nonsense! The ATP6-gene clusters bony fish, amphibians, birds and Reptilia. But some mammals, Monotremes, lay eggs; and some fishes, Cyprinodonts, give birth to live young. If Jeanson’s idea was right, we should expect Monotremes to group with fish and the rest, and Cyprinodonts to group with Mammals (or, alternatively, form separate groups). They do not. They end up in the system exactly where they should according to evolution. Trust me, I have checked. Or check for yourself.8

If I understand Frello’s logic here correctly, he seems to be arguing the following:

- Frello thinks that I argued that the ATP6-gene sub-cluster shows perfect correlation with the egg-laying vertebrate species.

- Frello thinks that I claimed only bony fish, amphibians, birds, and reptiles lay eggs—and only eggs, never any live-bearers among these groups.

- Since some mammals lay eggs, yet they are not found in the ATP6-gene sub-cluster, and since some fish bear live young, yet are not found outside the ATP6-gene sub-cluster, my hypothesis is falsified.

On point (1) of Frello’s logic, here’s what I actually claimed (Jeanson 2013):

This protein “moonlighting” hypothesis is consistent with the observation that the protein clusters found in this study transcend Linnaean classification categories—categories which sometimes separate (rather than cluster) species that share a functional trait. For example, bony fish, amphibians, birds, and most reptiles share the reproductive strategy of laying eggs, but these species are divided into separate Linnaean classes. In contrast, the ATP6 sequence comparison in this study joined species from Actinopterygii, Amphibia, Aves, and Reptilia into a vertebrate sub-cluster (Fig. 2). Hence, the clustering patterns I observed might be explained in part by functions shared by multiple taxonomic categories (pp. 496–497, emphasis added).

I did not claim that this was a perfect correlation— again, because the data indicated otherwise:

This artificial taxonomic template (Fig. 15) clearly identified some of the clustering patterns I observed for the mitochondrial protein sequence alignments (R2 value between Fig. 2 and Fig. 15 is equal to 0.79). For example, the template identified the Arthropoda and vertebrate clusters, as well as the Actinopterygii, Aves, Mammalia, and Testudines clusters (compare Fig. 15 to Figs. 2–14). The template also isolated some of the major phyla, such as Cnidaria, Echinodermata, Nematoda, and Porifera (Fig. 15). However, the template did not identify all the clusters observable in the protein alignment results, such as the sub-cluster within vertebrates (including the classes Actinopterygii, Aves, Amphibia, and Mammalia, and members [Squamata, Testudines] of the former class Reptilia). It also failed to identify the clustering that occurred among Cnidaria and Porifera (compare Fig. 2 to Fig. 15). Thus, the overlap between the taxon-based heat map and protein sequence-based heat map indicated that taxonomic rank and grouping partially explained the clusters but did not explain all the mitochondrial protein sequence patterns (Jeanson 2013, pp. 490– 491, emphasis added).

Finally, if you visually examine fig. 2 (from the Jeanson 2013 paper), you’ll quickly see that bony fish, amphibians, birds, and reptiles do not form a perfect sub-cluster. For examples, Serpentes (i.e., snakes) appear to form their own cluster separate from bony fish, amphibians, birds, and some Reptilia. Thus, I was making an observation of a general pattern.

Therefore, point (1) in Frello’s logic is a straw man.

With respect to point (2), I never claim that only bony fish, amphibians, birds, and reptiles lay eggs—and only eggs, never any live-bearers among these groups. Instead, I was making observations of general patterns.