The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

Many have noted that the worship practices of Israel share elements in common with nations around them, including a sacrificial system, a sanctuary, and priests, leading secular scholars to conclude that the worship practices of ancient Israel arose as mere evolutionary developments from other Near Eastern religions. In this essay, I will focus on one primary line of argumentation used to conclude that Israel’s monotheistic worship evolved naturally from polytheism. I begin with an explanation of the problems of similarity between the worship of Israel and its pagan neighbors. I then survey common answers to the question of similarity. I conclude by arguing that worldview bias plays a significant role in the conclusions drawn from the available data, and I observe that non-theists who discredit the veracity of the biblical record by appealing to historical accuracy do so only on the basis of the biblical worldview they repudiate.

Keywords: Old Testament, worship, monotheism, worldview

Challenges for the Biblical Origin of Hebrew Worship

The Old Testament claims that Israel’s monotheistic worship appeared at the outset of their history as a direct result of revelation from God. According to some scholars, “there is not a shred of evidence outside the Bible to corroborate these claims” (Greenberg 2008, 1). Further, they argue that historical evidence actually contradicts the biblical account and proves it is fallacious. They draw attention to the multiple similarities between Hebrew worship and that of their Canaanite neighbors, leading to theories of the origin of Hebrew worship that contradict the biblical account.

Similarities Between Pagan and Hebrew Worship

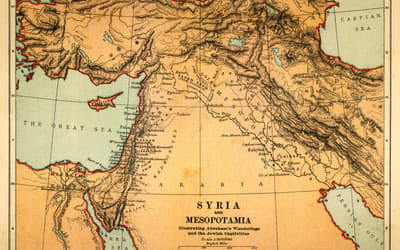

Secular scholars claim that similarities between Israel’s worship, as described in the Old Testament, and worship of other nations, as discovered through archaeology, prove that Israel’s worship finds its roots in the religion of its neighbors rather than from divine revelation as the Bible asserts. One of the most significant archaeological discoveries concerns documents uncovered in 1929 from the Syrian coastal town of Ugarit dating from 1300–1200 BC. Scholars believe this group of people to be the biblical “Canaanites,” and thus study of these discoveries provides a wealth of information about Israel’s neighbors (Greenstein 2010, 48). Documents discovered include literary, ritual, and liturgical texts (Gibson 1978; Pardee 2002; Parker 1997; Wyatt 1998), several of which non-theists use to prove that Israel’s worship was essentially Canaanite in origin.1

Comparison of the Bible’s descriptions of Israel’s worship with that of the Ugarit people uncovers remarkable similarities, which fall into several categories. First, names for deity often overlap. For example, Ugarit documents reveal that the Canaanite name for the highest deity of the pantheon was El (Cross 1973, 13; del Olmo Lete 2004; Driver 1956; Pardee 2002; Smith 2003, 135), a title used throughout the Pentateuch for Israel’s God as well.2 Indeed, even Israel’s name contains this reference to deity (Smith 2003, 143), and in a particularly poignant passage, God himself tells Moses, “I am the Lord [‘Yahweh’]. I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, as God Almighty [‘El Shaddai’], but by my name the Lord [‘Yahweh’] I did not make myself known to them” (Exodus 6:2–3).3

Second, some argue that internal evidence within the Bible itself supports the claim that early Israel was polytheistic. For example, citing Genesis 6:1–4, which refers to “the sons of God,” Rollston argues that the Hebrew term “is semantically and etymologically cognate to the Ugaritic term bn ‘ilm, as well as to the various terms in Akkadian” (Rollston 2003, 102) and refers to Israel’s early belief in a pantheon of gods.

Third, some claim that later Israelites understood a hierarchy within the pantheon. The Canaanites believed in an “Assembled Body” of gods who operated under El’s rule (Pritchard 1955, 130). Rollston uses Job 1:6 (cf. also 2:1) to argue that Israel, like its neighbors, believed that Yahweh was the head of the pantheon when it states, “Now there was a day when the sons of God came to present themselves before the Lord” (Rollston 2003, 106).

Fourth, the worship systems of Israel and her neighbors are remarkably similar. The temples of Israel and of other religions often had comparable structure and purpose (Smith 2003, 136).4 Not only did most nations share in common the practice of sacrificial rites (DeBoer 1972, 33; Gray 1965, 192; Levine 1974, 8–20), Canaanite religion shared even essentially identical rituals such as the “scapegoat” (Leviticus 16) and other purification rituals (Wright 1987, 46).

Finally, some argue direct borrowing between Israelite worship materials and their neighbors. For example, Psalm 104 appears to evidence close parallels with the Ugaritic Baal cycle (Craigie 1974). Even more significantly, some scholars have argued that Psalm 29 is actually directly borrowed from Ugaritic poetry (Craigie 1979; Cross 1950; Dahood 1966; Fensham 1963; Kloos 1986).

Secular Theories of the Origin of Hebrew Worship

Based on similarities between Israel’s worship and the worship of its neighbors, secular scholars claim that the correspondences “point to a larger religious tradition shared broadly by West Semitic peoples, including the Israelites” (Smith 2003, 17). Therefore the worship of Israel—a nation that emerged relatively late5—must have evolved from the worship of these other older nations. To “claim that religion during the period of the state of Judah is accurately reflected in the final form of the text can be dismissed as naïve” (Edelman 1996, 17–18).6 Most secular (and even some Christian) Old Testament scholars advocate a version of the documentary hypothesis, popularized in 1895 by Julius Wellhausen, which argues that the Pentateuch was composed in its present form by a group of editors who compiled a diverse collection of writings, none of which dates to earlier than 900 BC (Archer 2007, 95). They base their argument primarily on internal evidence demonstrating different names used to describe Israel’s God, which they believe implies multiple authorship, combined with the fact that no earlier manuscripts for the Pentateuch have been discovered. Furthermore, some believe that Moses could not have written the Pentateuch, as the Bible itself claims,7 since “the art of writing was virtually unknown in Israel prior to the establishment of the Davidic monarchy; therefore there could have been no written records going back to the time of Moses” (Archer 2007, 175). As Archer notes, this assertion has no support.

This leads to a theory suggesting that a group of Hebrew editors composed the Pentateuch after the return of Israel from exile out of a desire to unify the struggling nation around a common religious heritage, most of which is fabricated from myths and legends. Diana Vikander Edelman states,

It is important to realize that the text of the Hebrew Bible is the product of a long, editorial process. Its final shapers were monotheistic and they wanted the inherited traditions to reflect their own religious beliefs in a single creator deity, Yahweh, who had at his command various lesser divine beings who also populated heaven, the angels. (Edelman 1996, 16–17)

This reasoning leads to certain conclusions among scholars who, with some variation, generally agree in their chronology of the evolution of Hebrew worship. Israel’s worship was initially polytheistic, although once Israel is established in the land, “Yahweh is considered the national deity” (Rollston 2003, 114). Later, “Yahweh becomes the head of the Israelite pantheon, but without a denial of the existence of other deities” (Rollston 2003, 114). Israel believed that “Yahweh was king of a whole heavenly host that included lesser deities who did his bidding, having various degrees of autonomy depending upon their status within the larger hierarchy” (Edelman 1996, 20). It is only later that “Israelite religion affirms the veracity of monotheism, with Yahweh as the sole deity, and with explicit denials of the existence of other deities” (Rollston 2003, 114).

If Israel’s worship was not, as the biblical record asserts, formed by direct revelation from the one true and living God, but rather was the result of natural religious evolution, then this is strong evidence that the Old Testament God does not exist.

Solutions to the Problem of the Origin of Hebrew Worship

Bible scholars have attempted to solve the problem of similarities between the worship of Israel and its neighbors in at least one of four ways.8

The Answer from Higher Criticism

One of the earliest answers to the logic presented above came from higher critics who attempted to “demythologize” Scripture by extracting the biblical “narrative” (Geschichte) from the historical “event” (Historie). They accept a post-exilic date for the composition of most of the Old Testament (Archer 2007, 99ff; Wellhausen 2013, 1ff), claim that the Old Testament’s historical genre “is firmly rooted in the worldview of its time” (Enns 2005, 27) and conclude that biblical events are “culturally descriptive rather than revealed truth” (Walton 2009, 19).

This attempt to explain similarities between Israelite and Canaanite worship by separating historical fact in Scripture from its spiritual significance is problematic, however, since “the theology of the Bible is presented as though it is an extrapolation from the experience of Israel and the Church” (Oswalt 2009, 15). As I shall argue below, the worship of Israel (and, later, Christianity) is predicated upon the historical veracity of Scripture. To deny that biblical events occurred exactly as recorded is to question the very validity of biblical religion.9

The Answer from Differences

One conservative explanation of similarities is to identify differences between Israel’s worship and that of other ancient Near East (ANE) nations and argue that differences are far more fundamental than surface-level similarities. This approach is epitomized recently by Oswalt, who insists that “the similarities between the Bible and the rest of the literature of the ANE are superficial, while the differences are essential” (Oswalt 2009, 47).

These differences are several. First, the Old Testament’s conception of God and that of other ANE religions is starkly different. While the Old Testament God had no beginning (Psalm 90:2), “the mythology of both Mesopotamia and Egypt makes clear that the gods had origins” (Walton 2006, 87). Furthermore, the “gods were not omnipotent but were restricted in power to the capacity of the natural elements they personified” (Currid 2013, 40). Pagan gods were part of the natural world, not above it. They “were manifest in that element of the cosmos with which they were associated, and had some jurisdiction there” (Walton 2006, 97), but no single deity exercised authority over all. In contrast, “so great was [the God of Israel] that the Israelite acknowledged his Lordship over every phenomenon that his experience encountered” (Wright 1950, 22).

This leads to another significant difference: while the deities of other nations were manifested in nature itself, the God of the Old Testament revealed himself in his works. Therefore, as Wright notes, “the basis of the [biblical] literature was history, not nature, because the God of Israel was first of all the Lord of history who used nature to accomplish his purposes in history” (Wright 1950, 28). The record and study of history is far more significant for Israel than for any other ANE nation, because “if the human experience is to be correctly understood, it is human behavior in creation in relation to God that must be studied and not the relations of the gods among themselves in primeval time” (Oswalt 2009, 79).

Third, while pagan worship had no central moral standard, Israel believed in moral absolutes rooted in God and revealed to them in his Law. Israel’s God, in contrast to the “depraved, perverted manner” (Currid 2013, 40) of pagan gods, is reliable and trustworthy. Oswalt notes that “the word hesed, a word not attested outside Hebrew, comes to be used as the descriptor par excellence of God in the Old Testament” (Oswalt 2009, 71).

Fourth, Israel’s monotheism stands in stark contrast to the polytheism of other nations. Even if one were to concede that monotheism emerged late in Israel’s history, the fact of Israel’s monotheism remains unprecedented. If monotheism were merely the natural evolution of religion from its earlier polytheism, one wonders why no other nation in the ANE evolved into monotheism.10

Fifth, although Israel shares with its neighbors similar worship places and rituals, each of these functions in often radically different ways. For example, unlike pagan sanctuaries, Israel’s temple was “not God’s palace where his human servants supplied his physical needs, but it was the bearer of his name” (Geraty 1981, 59). Furthermore, pagan worship was initiated by the worshiper who desired to attract the god’s attention and earn favor, while Israel’s God initiated the worship, and the worshipers simply responded to what God has already done for them.11

When comparing the psalms of Israel with those of Ugarit people, important distinctions emerge as well. According to Walton, “the category of declarative praise is unique to Israel” (Walton 1994, 145). Oswalt argues that although Psalm 29 may resemble Ugarit references to Baal as god of thunderstorms, “nowhere in the psalm is Yahweh identified with the thunderstorm. . . . Yahweh sits above the flood” (Oswalt 2009, 105–06. Emphasis original).

Each of these differences reveals an even more essential distinction between the worship of Israel and that of other ANE nations, and that is one of worldview. Oswalt thoroughly demonstrates that the beliefs and practices of other nations are rooted in a worldview of what he calls “continuity.” Religious beliefs of the Canaanites flowed out of the principle that “all things that exist are physically and spiritually part of one another” (Oswalt 2009, 49). They believed that the gods themselves were created out of eternal, preexisting matter, and thus the gods are part of nature rather than above it. Israel’s worldview, on the other hand, was characterized by “transcendence,” the belief that “the Creator of the universe is radically other than his creation” (Oswalt 2009, 193). Israel’s God created all things from nothing and remains above all things as the supreme ruler. All of humankind’s existence, then, is interpreted in light of their relationship to the Creator God.

Because of these different conceptions of deity that flow from fundamentally opposing worldviews, the literary genre of historical record differed for Israel than for other nations. Oswalt observes, “whatever the biblical narratives are, they are in a different category altogether” (Oswalt 2009, 15). Walton agrees, noting that “Historiography in Israel was driven by the covenant, not by the king. In the rest of the ancient Near East historiography had the function of promoting and legitimating the king” (Walton 2006, 333). While Old Testament authors knew nothing of the “journalistic” historical record of modern times, the Israelites gave much more attention to their own history, “because that is where God is known: in the human-historical world of ethical choices” (Oswalt 2009, 79). Likewise, Currid observes that even “the style of writing of the cosmological texts from the ancient Near East is best described as ‘mythic narrative,’” while the biblical record “bears all the markings of Hebrew historical narrative” (Currid 2013, 43).

This is an important reason that the biblical record has no parallel in ANE literature and thus cannot be interpreted by direct comparison with pagan mythology. Biblical history and pagan myth have very different purposes, functions, and literary forms and therefore must not be interpreted in the same manner.

The Answer from Similarities

A second way to defend the Old Testament’s claim that Israel’s worship came by revelation from God is to explain reasons for the similarities consistent with the biblical record and actually argue for the truth of Scripture from the similarities. This is the method employed by Currid, who argues that “many of the parallels between ancient Near Eastern literature and the Old Testament . . . may be properly and fully understood only through the right use of polemical theology” (Currid 2013, 31). He shows that every significant correspondence can be explained as biblical authors “borrowing for the purpose of taunting” (Currid 2013, 27). He cites such examples as Yahweh’s “strong arm” in Exodus 3, use of the idiom “Thus says” in Exodus 5, and the image of a heavenly rider in Isaiah 19.

Even more significantly, unquestionable similarities between many primary characteristics of Hebrew worship and other nations could be evidence, not for the fact that Israel’s worship evolved from other nations, but rather that the worship of other nations evolved (or, better, devolved) from elements of worship that existed from Creation. If one posits the truthfulness of the Old Testament, then it would make sense for all nations to share similar conceptions of deity and of the way to approach deity in worship, including similar language. The key elements of worship that appear in most religions are instituted in the first few chapters of Genesis. God places Adam and Eve in his sanctuary (Wenham 1986) as priests (Ross 2006, 105–06) who serve him and commune with him. After they disobey him, God institutes the idea of substitutionary sacrifice and atonement, establishing a covenant with them. Each of these elements characterizes the worship of all religions since they are part of the religious heritage of all children of Adam. As Rodríguez notes, “those religious expressions belong to the common human experience of God” (Rodríguez 2001, 47). Romans 1:19–20 testifies to this when it says that God has revealed himself to all people through “the things that have been made.” It is the pagans, then, who already operate on the basis of God’s revelation, and this is further proven by the fact that all religions of the world—not just those of the ANE—share many of the essential similarities discussed above (Meister 1978, 373; Steinhardt 1978, 382; Turner 1979, 28). As Walton summarizes, “this reflects the common nature of humanity, not literary dependence” (Walton 1994, 145). Thus similarities between worship practices of various nations actually provide proof for the God of Scripture.12

The Answer from Worldview Bias

A final, perhaps more fundamental defense of biblical origins for Hebrew worship emerges from this study, which reveals two distinct and contradictory worldview biases implicit in the interpretation of historical data by non-theists. When viewed this way, the non-theist’s argument collapses under its own weight.

Secular scholars argue that when the narratives of the Old Testament are measured against modern methods of historical analysis, they prove to be factually unreliable. Yet no archaeological discoveries or ancient texts explicitly state the conclusions these scholars claim with authority. Non-theists arrive at their conclusions because of the naturalist and Darwinian presuppositions that underlie their interpretation of the data. As Merrill notes, “No fragment of information—literary or otherwise—is self-interpreting; it always calls for outside help to give it meaning” (Merrill 2009, 8). Archaeology, for example, is hardly an exact science, but is “fraught with methodological difficulties, for the silent archaeological evidence may always be interpreted in more ways than one” (Mazar 1992, 281). Conservative Christians and non-theists possess the same data, both biblical and extra-biblical; differences in their interpretation of that data emerge from distinct starting presuppositions—conservative Christians presuppose the existence of God and the veracity of the biblical record, while non-theists presuppose naturalist assumptions. Therefore, each of the similarities cited above finds the best rational explanation when one posits that what the Bible records really did happen just as it said.13

But perhaps even more damaging to the non-theist’s argument is the fact that appeal to scientific accuracy and historical veracity is itself predicated upon a transcendent—and, thus, biblical—worldview. As Paul Davies asserts, “Science began as an outgrowth of theology, and all scientists, whether atheists or theists . . . accept an essentially theological worldview” (Davies 1995, 138). Diligent study of the cosmos makes no sense in a worldview of continuity; it was motivation to understand what God had made that fueled the seventeenth-century Scientific Revolution. Likewise, a desire to discover “what really happened” historically makes sense only within a worldview of transcendence. A consistent naturalist has no reason to assume that human choices are important or have consequences, nor does he have any philosophical basis for insisting upon scientifically accurate historical record. It is only a worldview of transcendence (of which the biblical worldview is the only one14), that has any cause for interest in history. Observing that Augustine’s City of God is arguably “the first expression of a philosophy of history to be found in the world,” Oswalt argues that such an interest in history on a broad scale was possible only in a civilization in which biblical values were taking root (Western Christendom). He explains,

That human experience is moving toward a goal through a series of linked causes and effects in the visible world, that there is a linear progression to new causes and effects, with measurable progress toward a goal, and that there is real human choice and concomitant human responsibility—these ideas find their origin in the Bible and are brought to systematic expression with the aid of Greek thought. Thus, the idea that the Bible is not ‘historical’ is something of an oxymoron. (Oswalt 2009, 111–12)15

Thus, non-theists have no basis within their own naturalist worldview to argue against the veracity of Scripture on scientific or historical standards.

Conclusion

Conservative Christians can answer the difficulties surrounding the origin of Hebrew worship fairly simply. They can direct attention to clear, fundamental differences between Israel’s worship and that of her neighbors, they can explain the similarities in terms of theological polemics, and they can demonstrate that similarities result from a more basic form of borrowing, that is, pagan nations reflecting an original understanding (albeit distorted) from God’s reality. The secular (and higher critical) views over-emphasize the similarities between biblical worship and that of the ANE while ignoring the overwhelming differences. Mostly starkly, these views fail to recognize the fundamental contrast between the worldview of ancient Israel and that of other nations. Positing the historical accuracy of the Old Testament and God as Creator and Revealer provides the most satisfying explanation for the evidence. All nations had a common ancestry in Adam, and God’s self-revelation was part of their heritage, thus accounting for any similarities in worship practice that exist.

But the most potent defense against charges that the Old Testament’s record of God revealing himself to Israel is historically inaccurate is to expose the naturalist presuppositions that lie beneath non-theist interpretation of archaeological and historical data and reveal the biblical foundation upon which any appeal to historical accuracy must be made in the first place. Only a worldview of transcendence can account for interest in history, and thus the Bible’s historical veracity concerning the origin of Hebrew worship is self-authenticating.

References

Archer, G. L. 2007. A Survey of Old Testament Introduction. 3rd ed. Chicago, Illinois: Moody.

Bahnsen, G. L. 1996. Always Ready: Directions for Defending the Faith. Nacogdoches, Texas: Covenant Media Foundation.

Bimson, J. J. 1989. “The Origins of Israel in Canaan: An Examination of Recent Theories.” Themelios 15 (1): 4–15.

Craigie, P. C. 1974. “The Comparison of Hebrew Poetry: Psalm 104 in Light of Egyptian and Ugaritic Poetry.” Semitics 4: 10–21.

Craigie, P. C. 1979. “Parallel Word Pairs in Ugaritic Poetry: A Critical Evaluation of Their Relevance for Psalm 29.” Ugarit-Forschungen 11: 135–40.

Cross, F. M. 1950. “Notes on a Canaanite Psalm in the Old Testament.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 117: 19–21.

Cross, F. M. 1973. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard.

Currid, J. D. 2013. Against the Gods: The Polemical Theology of the Old Testament. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway.

Dahood, M. 1966. Psalms. Vols. 1–3. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

Davies, P. 1995. Are We Alone? Philosophical Implications of the Discovery of Extraterrestrial Life. New York, New York: Basic Books.

DeBoer, P. A. H. 1972. “An Aspect of Sacrifice.” In Studies in the Religion of Ancient Israel, Vetus Testamentum Supplement 23: 27–47.

del Olmo Lete, G. 2004. Canaanite Religion: According to the Liturgical Texts of Ugarit. Bethesda, Maryland: Eisenbrauns.

Driver, G. R. 1956. Canaanite Myths and Legends. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: T & T Clark.

Edelman, D. V. ed. 1996. The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans.

Enns, P. 2005. Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker.

Fensham, F. C. 1963. Studies in the Psalms. Potchefstroom, South Africa: Pro Rege.

Geraty, T. 1981. “The Jerusalem Temple of the Hebrew Bible in Its Ancient Near Eastern Context.” In The Sanctuary and the Atonement: Biblical, Historical, and Theological Studies. Edited by A. V. Wallenkampf and W. R. Lesher. Washington, DC: Review and Herald.

Gibson, J. C. 1978. Canaanite Myths and Legends. 2nd ed. New York, New York: T & T Clark.

Gray, J. 1965. The Legacy of Canaan: The Ras Shamra Texts and Their Relevance to the Old Testament. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Greenberg, G. 2008. The Moses Mystery: The Egyptian Origins of the Jewish People. 3rd ed. New York, New York: Pereset Press.

Greenstein, E. L. 2010. “Texts from Ugarit Solve Biblical Puzzles.” Biblical Archaeology Review 36 (6): 48.

Kloos, C. 1986. Yhwh’s Combat with the Sea: A Canaanite Tradition in the Religion of Ancient Israel. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Levine, B. A. 1974. In the Presence of the Lord. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Lewis, C. S. 2001. The Abolition of Man. New York, New York: HarperOne.

Lewis, C. S. 2002. Mere Christianity. San Francisco, California: HarperSanFrancisco.

Lundquist, J. 1983. “What Is a Temple? A Preliminary Typology.” In The Quest for the Kingdom of God: Studies in Honor of George E. Mendenhall. Edited by H. B. Huffmon, F. A. Spina, and A. R. W Green. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Machinist, P. 1991. “The Question of Distinctiveness in Ancient Israel: An Essay.” In Ah, Assyria: Studies in Assyrian History and Ancient Near Eastern Historiography. Edited by M. Cogan and L. Eph’al. Jerusalem, Israel: Magnes Press.

Mazar, A. 1992. “The Iron Age.” In The Archaeology of Ancient Israel. Edited by A. BenTor. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

Meister, M. W. 1978. “Temple: Hindu Temples.” In vol. 13 of The Encyclopedia of Religion. Edited by M. Eliade. New York, New York: Macmillan.

Merrill, E. H. 2008. Kingdom of Priests: A History of Old Testament Israel. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic.

Merrill, E. H. 2009. “Old Testament Archaeology: Its Promises and Pitfalls.” Journal of Dispensational Theology 13 (39): 5–20.

Oliphint, K. S. 2013. Covenantal Apologetics: Principles and Practice in Defense of Our Faith. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway.

Oswalt, J. N. 2009. The Bible among the Myths: Unique Revelation or Just Ancient Literature? Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

Pardee, D. 2002. Ritual and Cult at Ugarit. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature.

Parker, S. B. ed. 1997. Ugaritic Narrative Poetry. Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press.

Pritchard, J. B. ed. 1955. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Robinson, J. 2010. “The God of the Patriarchs and the Ugaritic Texts: A Shared Religious and Cultural Identity.” Studia Antiqua 8 (1): 25–33.

Rodríguez, A. M. 2001. “Ancient Near Eastern Parallels to the Bible and the Question of Revelation and Inspiration.” Journal of the Adventist Theological Society 12 (1): 43–64.

Rollston, C. A. 2003. “The Rise of Monotheism in Ancient Israel: Biblical and Epigraphic Evidence.” Stone-Campbell Journal 6 (1): 95–115.

Ross, A. P. 2006. Recalling the Hope of Glory: Biblical Worship from the Garden to the New Creation. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel.

Smith, M. S. 1994. The Ugaritic Baal Cycle. Vol. 1. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Smith, M. S. 2003. The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel’s Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Steinhardt, N. S. 1978. “Temple: Confucian Temple Compounds.” In vol. 13 of The Encyclopedia of Religion. Edited by M. Eliade. New York, New York: Macmillan.

Turner, H. W. 1979. From Temple to Meeting House: The Phenomenology and Theology of Places of Worship. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton.

Walton, J. H. 1994. Ancient Israelite Literature in Its Cultural Context: A Survey of Parallels Between Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

Walton, J. H. 2006. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic.

Walton, J. H. 2009. The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press.

Wellhausen, J. 2013. Prolegomena to the History of Israel: With a Reprint of the Article “Israel” from the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Translated by J. S. Black and A. Menzies. Reissue edition. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Wenham, G. J. 1986. “Sanctuary Symbolism in the Garden of Eden Story.” In I Studied Inscriptions Before the Flood: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1–11. Edited by R. S. Hess and D. T. Tsumura, 399–404. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Wright, D. P. 1987. The Disposal of Impurity: Elimination Rites in the Bible and in the Hittite and Mesopotamian Literature. Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press.

Wright, G. E. 1950. The Old Testament Against Its Environment. London, United Kingdom: SCM Press.

Wyatt, N. 1998. Religious Texts from Ugarit: The Words of Ilimilku and His Colleagues. 2nd ed. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press.