The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

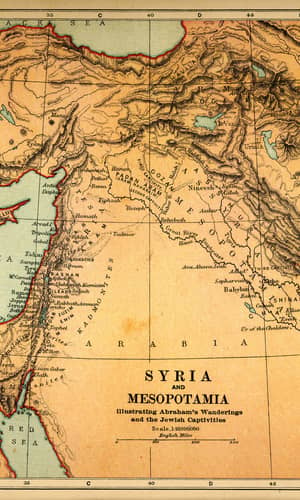

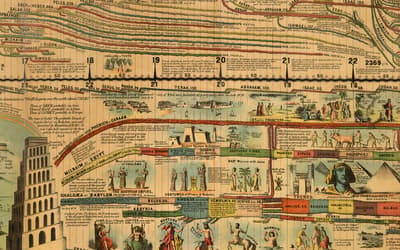

Biblical chronology is an essential component of the young-earth creationist perspective, because it provides a way to calculate the age of the earth by working backward through biblical data from a fixed point in history. The renowned chronologist James Ussher used an anchor date of 562 B.C. for the death of Nebuchadnezzar, and together with biblical events covering a time span of 3,442 years suggested the earth was created in 4004 B.C.

As new archaeological and historical material has been discovered since Ussher’s original publication in the 1650s, other chronologists like Edwin Thiele, Leslie McFall, and Rodger Young have made significant contributions to the current understanding of biblical chronology through their careful and reasoned scholarship. Their work reflects the biblical standard set forth in Titus 2:7–8 (ESV) that says, “in your teaching show integrity, dignity, and sound speech that cannot be condemned.”

Now is an opportune time to compare Ussher’s chronology to these more recent advancements, first because of the progress made in this area of study, and second because of the access that digitization currently provides for the archaeological data used to tie biblical chronology to absolute dates in modern calendar terms. Ussher started with an anchor point in 562 B.C., but other anchor dates have also been found that reach even further back into the history of Israel and Judah.

Additionally, historical manuscripts show remarkable harmony of testimony with each other and with events described in God’s Word. Their consistent witness affirms and supports the accuracy and reliability of the Bible. This article offers a summary of such records so that readers have a convenient overview of the applicable texts that relate to the Old Testament.

Keywords: chronology, archaeology, ancient Near East, divided kingdom, Israel, Judah, Assyria, Babylonia, Phoenicia, Ahab, Jehu, Hezekiah, Shalmaneser, Tiglath-pileser, Pul, Sargon, Sennacherib, Merodach-baladan, James Ussher, Larry Pierce, Edwin Thiele, Leslie McFall, Rodger Young, Andrew Steinmann

Introduction

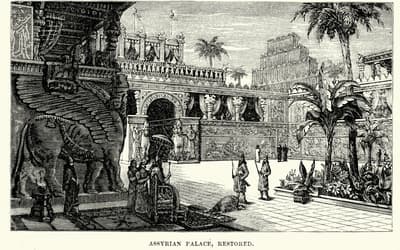

Biblical chronology is integral in a young-earth framework because it provides the basis for estimating a 6,000 year age for the earth. The creationist community appropriately acknowledges the impressive work of James Ussher, who produced a biblical chronology in the 1650s titled The Annals of the World (Ussher 1658). This was only a starting point, however, because a wealth of archaeological data was published in the 1800s and 1900s that offered much greater precision for dating events during the divided kingdom period when the Jewish people lived in separate nations, Israel in the north and Judah in the south.

In the 1940s, chronologist Edwin Thiele used the recently discovered historical records to make refinements to biblical chronology. His work was first introduced in a 1944 journal article (Thiele 1944), then in a book titled The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, published in three editions (Thiele 1951, 1965, 1983). He did not solve every issue, but others who examined his work made suggestions or added improvements. Leslie McFall was among these contributors, and he offered a modified chronology in a 1991 journal article (McFall 1991).

Between 2003 and 2005, chronologist Rodger Young made a series of discoveries that resolved a few remaining issues in Thiele’s chronology (Young 2003, 2004a, 2004b, 2005). Perhaps most notably, Young’s efforts revealed cross-checks within biblical dating systems that tie to one another through various Bible passages and also agree with dates recorded in secular history from countries neighboring Judah and Israel. Young’s work is treated as foundational to establishing benchmarks in time in Andrew Steinmann’s 2011 book, From Abraham to Paul: A Biblical Chronology (Steinmann 2011).

These advancements are not yet widely known, however, and some Christian circles still promote older material without knowledge of methodological problems that have been exposed in Ussher’s chronology. This article seeks to compare the older and newer biblical chronologies, and to take advantage of the widespread digitization of books and articles that has made the topic readily accessible for analysis. Of the 47 sources listed in this article’s reference section, only two are not freely available online; one is a translation of Ussher’s work by Larry and Marion Pierce in 2003 (Ussher 2003; an alternative digital English translation is available, Ussher 1658) and the other is Steinmann’s recently published book.

Larry Pierce advocated Ussher’s chronology in 2001 in an article called “Evidentialism: The Bible and Assyrian Chronology” (Pierce 2001) and offered the calculation methods he believes support that chronology in an attached “Addendum” link with dates for the divided kingdom period (Pierce 2001, reference 16). These pieces appeared in TJ (Technical Journal), a precursor of Answers Research Journal (of Answers in Genesis) and Journal of Creation (of Creation Ministries International). The article drew a response from McFall, who disagreed with the accusations leveled against him by Pierce (McFall 2002; Dr. McFall recently passed away in 2015). Later, in 2018, Young weighed in on Pierce’s criticisms of Thiele that appeared in Pierce’s 2003 translation of Ussher’s Annals of the World (Ussher 2003; Young 2018, 51).

This paper compares the two chronological approaches and also highlights a wide array of historical texts and archaeological finds relevant to dating events recorded in the Old Testament. For simplicity, the combined Ussher-Pierce Chronology will be abbreviated “UPC” and the Thiele-McFall-Young Chronology “TMYC.” UPC dates for the divided kingdom are taken from two tables in the Pierce 2001 Addendum (Pierce 2001, link embedded in reference 16, Addendum pages 5-6). TMYC dates for this period are pulled from two summary tables found in the Beckman 2021 Supplementary File (Beckman 2021, link embedded on page 75 in blue text ‘supplementary tables 2a and 2b,’ pages 1–6). Tables compiled in the current article are either intended to concisely demonstrate calculation methods or to offer a convenient overview of the numerous sources of historical testimony that harmonize with the biblical account of human events.

Preliminaries—Differences in Measurement and Precision

The divided kingdom, according to the UPC, began in 975 B.C., about 44 years earlier than the TMYC date of 931 B.C. Both the UPC and TMYC systems, however, arrange dates for the reigns of the kings in such a way that each chronology is still able to fit together all of the synchronizations between Israel and Judah.

Synchronizations have a formula like this: “In the nth year of [name a] king of [either Israel or Judah], [name b] began to rule in [the other kingdom], and he reigned x years.” When UPC dates are plugged into these formulas, the synchronizations line up with “some leeway of about one year” (Pierce 2001, Addendum 6). When TMYC dates are calculated, the synchronizations agree precisely to a six-month period based on the overlap of the measurement units used by the two kingdoms. Rodger Young (2018, 54) explains why such exactness is necessary:

[Ussher] showed that he thought that the Bible’s chronological figures were only approximate. However, this is not the way court records were kept in the ancient Near East, where years of reign were used for legal contracts and other matters and therefore had to be precise. It is difficult to conceive that the Author of the Bible would go to such lengths in giving us the abundant and complex chronological data for the kingdom period while at the same time His figures were not as accurate, according to Ussher, as those of Israel’s contemporaries in the surrounding nations.

Thiele’s precision of measurement was achieved through two observations. First, Judah measured time by Tishri years while Israel used Nisan years. Nisan was the name of the first month by the biblical numbering system, and it began in springtime. At the time of the Israelite exodus out of Egypt, it was called Abib/Aviv (Exodus 13:4, 23:15, 34:18; Deuteronomy 16:1) and God designated it as the first month of the religious year (Exodus 12:2). Tishri, by comparison, was the name of the seventh month, and it began in autumn. During Solomon’s reign, this month was called Ethanim (1 Kings 8:2). After the northern kingdom of Israel was exiled by the Assyrians, and the southern kingdom of Judah by the Babylonians, God’s people adopted the name Nisan for the first month and Tishri for the seventh (Steinmann 2011, 15–21). For simplicity, these later names are used for notation. The letter “n” is used for Nisan years that began in spring, and “t” for Tishri years that began in fall. A year designated 967n, for example, would have begun in the spring of 967 B.C. The first six months of 967n would correspond to the last six months of 968t, which would have begun in the fall of 968 B.C.

Second, Thiele realized that neither kingdom remained consistent in its use of accession or non-accession reckoning. In the accession year system, in the year that the old king died and the new king came to the throne, that transition year was credited only to the old king’s years of reign. For the new king, it was simply called an accession year, and his reign length count would begin with the following year as the first official year of his reign. In the non-accession year system, the transition year was double counted to both the old and the new king, resulting in an inflation of one year for each new king when summing the reign lengths of the kings over a span of time.

The UPC assumes that both Judah and Israel used Nisan years for recording kings’ reigns (Pierce 2001, Addendum 2), while Thiele found that Tishri years were used to measure Solomon’s reign and the reigns of the kings of Judah. He offered these examples:

Example 1: Solomon–1 Kings 6:1, 38

In the four hundred and eightieth year after the people of Israel came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month, he began to build the house of the Lord. . . . And in the eleventh year, in the month of Bul, which is the eighth month, the house was finished in all its parts, and according to all its specifications. He was seven years in building it.

By measuring the time in both Nisan and Tishri years, Thiele found that only a Tishri year measurement system fit into the seven-year timeframe listed in the Bible (Thiele 1944, 142; table 1).

| Nisan half year | If Nisan 1 was start . . . | Tishri half year | If Tishri 1 was start . . . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year 4 first half | 967n1 (mos 2–6) | Year 4 second half | 968t2 (mos 2–6) |

| Year 4 second half | 967n2 (mos 7–12) | Year 5 first half | 967t1 (mos 7–12) |

| Year 5 first half | 966n1 (mos 1–6) | Year 5 second half | 967t2 (mos 1–6) |

| Year 5 second half | 966n2 (mos 7–12) | Year 6 first half | 966t1 (mos 7–12) |

| Year 6 first half | 965n1 (mos 1–6) | Year 6 second half | 966t2 (mos 1–6) |

| Year 6 second half | 965n2 (mos 7–12) | Year 7 first half | 965t1 (mos 7–12) |

| Year 7 first half | 964n1 (mos 1–6) | Year 7 second half | 965t2 (mos 1–6) |

| Year 7 second half | 964n2 (mos 7–12) | Year 8 first half | 964t1 (mos 7–12) |

| Year 8 first half | 963n1 (mos 1–6) | Year 8 second half | 964t2 (mos 1–6) |

| Year 8 second half | 963n2 (mos 7–12) | Year 9 first half | 963t1 (mos 7–12) |

| Year 9 first half | 962n1 (mos 1–6) | Year 9 second half | 963t2 (mos 1–6) |

| Year 9 second half | 962n2 (mos 7–12) | Year 10 first half | 962t1 (mos 7–12) |

| Year 10 first half | 961n1 (mos 1–6) | Year 10 second half | 962t2 (mos 1–6) |

| Year 10 second half | 961n2 (mos 7–12) | Year 11 first half | 961t1 (mos 7–8) |

| Year 11 first half | 960n1 (mos 1–6) | 14 half-year blocks or 7 years | |

| Year 11 second half | 960n2 (mos 7–8) | ||

| 16 half-year blocks or 8 years | |||

Example 2: Josiah of Judah—2 Kings 22:3-23:23; 2 Chronicles 34:8-35:19

Both passages list a great deal of activity that took place in the eighteenth year of Josiah, starting with the repair of the temple, finding the Book of the Covenant, consulting Huldah the prophetess, gathering the people of Judah and Jerusalem, and reestablishing the keeping of the covenant with the Lord. It is also possible that some of the cleansing of the temple and the land from idolatry took place during this time. If Josiah of Judah had reckoned his reign in Nisan years, all of the activity described in the passages had to have been accomplished in 14 days, between Nisan 1 when Josiah’s eighteenth year began, and Nisan 14 when Passover began (Thiele 1944, 142–143). If Josiah’s reign was recorded according to Tishri years, however, his eighteenth year would have begun in autumn, on Tishri 1, and he would have had six months before the spring month of Nisan arrived.

In reexamining the work of Ussher, Young found another example of Judah’s practice of measuring kings’ reigns by Tishri years (2018, 53–54).

Example 3: Abijam/Abijah of Judah—1 Kings 15:1–2, 8–9

Now in the eighteenth year of King Jeroboam the son of Nebat, Abijam began to reign over Judah. He reigned for three years in Jerusalem. . . . And Abijam slept with his fathers, and they buried him in the city of David. And Asa his son reigned in his place. In the twentieth year of Jeroboam king of Israel, Asa began to reign over Judah.

In the early part of the divided kingdom, Judah used accession reckoning while Israel used non-accession (table 2). For synchronizations to the start and end of the reign of Abijam/Abijah, his reign in Judah requires one accession year plus three years of reign to fit into an inclusive three years from Jeroboam’s eighteenth to twentieth years in Israel. This only works if Judah was using Tishri years while Israel used Nisan years (table 3).

| Judean kings with accession reckoning | Years of reign | Israelite kings with non-accession reckoning | Years of reign | Inflation effect of counting accession year as first year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rehoboam 1 Kings 14:21 2 Chronicles 12:13 |

17 | Jeroboam I 1 Kings 14:20 |

22 | |

| Nadab 1 Kings 15:25 | 2 | 1 year | ||

| Abijam/Abijah 1 Kings 15:1–2 2 Chronicles 13:1–2 |

3 | Baasha 1 Kings 15:28, 33 |

24 | 1 year |

| Elah 1 Kings 16:8 | 2 | 1 year | ||

| Asa (until Omri’s death, when Ahab became king) 1 Kings 16:29 |

38 | Zimri and Tibni 1 Kings 16:10, 15, 21–23 |

0 | Zimri’s reign was only 7 days; Tibni’s overlapped Omri’s |

| Omri 1 Kings 16:21–23 |

12 | 1 year | ||

| Total in Judah | 58 | Total in Israel | 62 | 4 years of inflation |

| Tishri year | Abijam/Abijah of Judah | Nisan year | Jeroboam I of Israel |

|---|---|---|---|

| 915t2 (mos 1–6) | Accession Year | 914n1 (mos 1–6) | Year 18 |

| 914t1 (mos 7–12) | Year 1 | 914n2 (mos 7–12) | Year 18 |

| 914t2 (mos 1–6) | Year 1 | 913n1 (mos 1–6) | Year 19 |

| 913t1 (mos 7–12) | Year 2 | 913n2 (mos 7–12) | Year 19 |

| 913t2 (mos 1–6) | Year 2 | 912n1 (mos 1–6) | Year 20 |

| 912t1 (mos 7–12) | Year 3 | 912n2 (mos 7–12) | Year 20 |

Comparison of Anchor Dates in the Two Chronologies

Thiele dedicated a chapter of his book to examining the work of Ussher and other modern chronologists (1951, 228–267). He noted that, because Ussher’s system had been added to the margins of some King James Bibles, “this system has come to be looked upon by many as the true system of Biblical chronology, and in many circles it receives almost the same veneration as does the sacred text itself” (Thiele 1951, 228).

Pierce seems to hold Ussher’s chronology in this regard, because he says “Ussher’s results, based on the Bible alone, violate just about every ‘absolute date’ in archaeology. Amen. All this shows is that we may not know as much about history as God does” (Pierce 2001, Addendum 24), and later “Dr. Thiele firmly declares that Samaria fell in 723 B.C. and adjusts the biblical chronology two years to shift the biblically deduced date of 721 B.C. to 723 B.C. (If the integrity of the scriptures was not at stake this is no big deal!)” (Pierce 2001, Addendum 38).

Thiele understood, however, that history accurately recorded, whether by ancient secular or Jewish sources, would together reflect the real events of the past. Thiele explains (1951, 151):

Let us remember that if history is to consist of fact rather than fiction, then the men of the world and the men of the Word must move along together in lands where time advances at an even pace. The years of the world in which the Assyrians lived kept constantly in accord with the years of the world in which the Hebrews lived. . . . If the chronology of the world in which the Assyrians and Babylonians lived moved along in tune with the stars, then the chronology of the world in which the Hebrews lived must likewise move along in tune with the same firmament of heaven—not faster or slower, but exactly right, and each in perfect accord with the other. . . . If the men of the Bible were real men [they were] and if the chronology of the Bible is a correct chronology [it is], then that chronology must be in perfect accord with the correct chronology of every other neighboring state.

Thiele’s words are also an apt reminder that God gave the sun, moon, and stars not just for light, but also “for signs and for seasons, and for days and years” (Genesis 1:14).

Ultimately, with any chronology, one or more of the events in biblical history needs to be tied to a date in secular history expressed in modern calendar terms. Ussher selected the death of Nebuchadnezzar in 562 B.C. as his anchor date, and added 3,442 A.M. years [Latin anno mundi, in the year of the world] to reach 4004 B.C. as the date of Creation (Ussher 1658, 7). Ussher had knowledge of this anchor date from Ptolemy’s Canon, a list of ancient Near East kings and their reign lengths that were tied to calendar dates with astronomical data (Depuydt 1995; Thiele 1951, 293). Pierce, in support of Ussher, also holds to 562 B.C. as the oldest reliable secular date (Pierce 2001, Addendum 2).

Ptolemy’s Canon is a key piece of evidence for both the UPC and TMYC, but the UPC only recognizes dates from the time of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, not the earlier dates from the Neo-Assyrian Empire that preceded it. The TMYC, in comparison, connects to the dates in Ptolemy’s records from both the Assyrian and Babylonian periods. The dates from the first part of Ptolemy’s Canon correspond to two other key historical sources, the Assyrian Eponym List and Babylonian Chronicle I (table 4), and the TMYC uses all three sources together to ascertain dates for biblical events that occurred in this timeframe. Occasionally the kings listed are identified by different names across these records, but the reign lengths and descriptions of events during the reigns are in agreement.

| Assyrian Eponym List name | Assyrian Eponym List dates | Babylonian Chronicle I name | Babylonian Chronicle I dates | Ptolemy’s Canon name | Ptolemy’s Canon dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University College London 2013; Thiele 1951, 287–292 | Grayson 2000, 69–82; Pinches 1887, 672–678 | Depuydt 1995, 98; Thiele 1951, 293 | |||

| Tiglath-pileser III | Assyrian accession 745 B.C. Eponym in 743 B.C. | Tiglath-pileser III | Assyrian accession 745 B.C. (third of Nabonassar) | Pulu/Pul | Accession year not listed |

| Tiglath-pileser III | Babylonian accession 729 B.C. (took the hand of Bel) Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 728 B.C. (took the hand of Bel) | Tiglath-pileser III | Babylonian accession 729 B.C. (third of Ukinzer/ (Nabu)-mukin-zeri) | Pulu/Pul | Combines two Babylonian kings Ukinzer/Mukin-zeri 731 B.C. year 1, not listing when he lost the throne and Pulu/ Pul took it |

| Tiglath-pileser III | End of reign(s) 727 B.C. (accession of successor) | Tiglath-pileser III | End of reign(s) 727 B.C. (died second year) | Pulu/Pul | End of reign(s) 727 B.C. |

| Shalmaneser V | Assyrian accession 727 B.C. | Shalmaneser V | Assyrian accession 727 B.C. | Ululai/Ululayu | Accession year is final year of predecessor |

| Shalmaneser V | (Assyrian/ Babylonian dual rule likely inherited from father) | Ululai/Ululayu | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 726 B.C. | ||

| Shalmaneser V | 725–723 B.C. Against [Samaria] Eponym in 723 B.C. | Shalmaneser V | Ravaged Samaria (only info between accession and death) | ||

| Shalmaneser V | End of reign(s) 722 B.C. (died fifth year) | Ululai/Ululayu | End of reign(s) 722 B.C. | ||

| A Chaldean rather than an Assyrian held the Babylonian throne at this time | Merodach-baladan | Babylonian accession 722 B.C. | Marduk-appal-iddin/ Merodach-baladan | Accession year is final year of predecessor | |

| Merodach-baladan | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 721 B.C. | Marduk-appal-iddin/ Merodach-baladan | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 721 B.C. | ||

| Merodach-baladan | End of reign(s) 710 B.C. (in twelfth year, fled from Babylon when Assyrian king Sargon attacked) | Marduk-appal-iddin/ Merodach-baladan | End of reign(s) 710 B.C. | ||

| Sargon II | No info on start or end of Assyrian reign; eponym in 719 B.C. | Sargon II | Assyrian accession 722 B.C. | ||

| Sargon II | Babylonian accession 710 B.C. | Sargon II | Accession year is final year of predecessor | ||

| Sargon II | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 709 B.C. (took the hand of Bel) | Sargon II | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 709 B.C. (took Bel’s hand) | Sargon II | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 709 B.C. |

| Sargon II | End of reign(s) 705 B.C. (inferred from a damaged line that lists the second year, which would have to refer to Sennacherib as the only one to rule between Sargon and Bel-ibni) | Sargon II | End of reign(s) 705 B.C. | ||

| Sennacherib | No info on start or end of Assyrian reign; eponym in 687 B.C. | Sennacherib | Assyrian first official year (yr 1) 704 B.C. (inferred from a damaged line that lists the second year, which would have to refer to Sennacherib as the only one to rule between Sargon and Bel-ibni) | First Interregnum (Sennacherib’s name was likely refused recognition because he decimated Babylon in 689 B.C.) | First Interregnum 704–703 B.C. |

| Sennacherib | First campaign records describe Sennacherib driving Merodach-baladan out of Babylon, plundering his palace, and setting Bel-ibni on the throne Sennacherib’s ‘first campaign’ records (Luckenbill 1924, 9–21; 1927, §234, 256–263, 270–273, 301) | Sennacherib | Second official year (yr 2) 703 B.C. (Sennacherib plundered Merodach-baladan’s land) | First Interregnum | First Interregnum 704–703 B.C. |

| Sennacherib and Bel-ibni | Babylonian accession year 703 B.C. (Sennacherib placed Bel-ibni on the throne in Babylon) | Bel-ibni | Accession year is final year of interregnum | ||

| Bel-ibni | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 702 B.C. | ||||

| Sennacherib | Fourth campaign records describe Sennacherib chasing Merodach-baladan out of Babylonia to take refuge in Elam, and Sennacherib setting his eldest son Assur-nadin-shum on the Babylonian throne Sennacherib’s ‘fourth campaign’ records (Luckenbill 1924, 9–21; 1927, §242–243, 313–315) | Sennacherib and Bel-ibni | End of reign(s) 700 B.C. (in third year, Sennacherib removed him from the throne) | Bel-ibni | End of reign(s) 700 B.C. |

| Sennacherib and Assur-nadin-shum/ Ashur-nadin-shumi | Babylonian accession year 700 B.C. (Sennacherib placed his son on the throne) | Assur-nadin-shum/Ashur-nadin-shumi | Accession year is final year of predecessor | ||

| Assur-nadin-shum/ Ashur-nadin-shumi | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 699 B.C. | Assur-nadin-shum/Ashur-nadin-shumi | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 699 B.C. | ||

| Assur-nadin-shum/ Ashur-nadin-shumi | End of reign(s) 694 B.C. (in sixth year, he was taken prisoner to Elam) | Assur-nadin-shum/Ashur-nadin-shumi | End of reign(s) 694 B.C. | ||

| The Assyrians did not have control over Babylon at this time | Elamite king and Nergal-ushezib | Babylonian accession year 694 B.C. (Elamite king placed him on the throne) | Nergal-ushezib | Accession year is final year of predecessor | |

| Nergal-ushezib | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 693 B.C. | Nergal-ushezib | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 693 B.C. | ||

| Nergal-ushezib | End of reign(s) 693 B.C. (captured by the Assyrian army) | Nergal-ushezib | End of reign(s) 693 B.C. | ||

| Mushezib-Marduk | Babylonian accession year 693 B.C. | Mushezib-Marduk | Accession year is final year of predecessor | ||

| Mushezib-Marduk | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 692 B.C. | Mushezib-Marduk | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 692 B.C. | ||

| Sennacherib | Eighth campaign records describe the destruction of the city of Babylon; Mushezib-Marduk is called Shuzubu and Sennacherib took him captive Sennacherib’s ‘eighth campaign’ records (Luckenbill 1924, 9–21; 1927, §252–254, 338–341, 352, 356–357) | Sennacherib and Mushezib-Marduk | End of reign(s) 689 B.C. (in the fourth year of his reign, the Elamite king became paralyzed and this may have been seen by the Assyrians as an advantageous time to attack Babylon when the city did not have an ally’s help; Sennacherib utterly destroyed Babylon and Mushezib- Marduk was taken captive) | Mushezib-Marduk | End of reign(s) 689 B.C. |

| Sennacherib | End of reign(s) 681 B.C. (in the eighth year of no king in Babylon, one of the key events mentioned was that Sennacherib, king of Assyria, was killed by his son) | Second Interregnum (Sennacherib’s name was likely refused recognition because he decimated Babylon in 689 B.C.) | Second Interregnum 688–681 B.C. | ||

| Esarhaddon | No info on Assyrian reign and no eponym | Esarhaddon (not the son who killed Sennacherib) | Assyrian accession 681 B.C. | Assur-akh-iddin/ Esarhaddon (he rebuilt Babylon and this may be why his name appears in Ptolemy’s Canon) | Accession year is final year of interregnum |

| Assyrian first official year (yr 1) 680 B.C. | Babylonian first official year (yr 1) 680 B.C. |

|

|||

Because the UPC dates do not align with Assyrian data, Pierce sought to cast doubt on the records of Assyrian king Shalmaneser III that Thiele used to locate a double set of anchor dates, in Nisan years 841n and 853n, a timeframe earlier than the records of Ptolemy’s Canon. This set of dates provided multiple clues helpful to Thiele’s chronological system. He had already discovered that early in the divided kingdom period Israel was using non-accession reckoning while Judah was using accession reckoning, simply by comparing biblical synchronisms. This was confirmed by the 12-year gap between Shalmaneser’s sixth and eighteenth years for which two Israelite kings claimed 14 years of reign (table 5, §3). Because of this fit, it also settled the last year of Ahab’s reign, in 853n, as well as Jehu’s accession year, in 841n (table 5, §2, 4). Further, the exactness of Ahab’s final year resolved an issue of a small discrepancy between the manuscripts of the Assyrian Eponym List. Thiele used a combination of biblical and secular data to persuade Assyriologists on the correct solution (Thiele 1944, 145–146, footnote 20; Thiele 1951, 287, bracketed note). For that reason, earlier composite presentations of the Assyrian Eponym List (Luckenbill 1927, §1198) differ slightly from current presentations (University College London 2013). But returning to the issue of whether Shalmaneser III’s records are reliable for the purposes of biblical chronology, this article will follow the same order as Pierce in his analysis (2001).

| Bible | Assyrian Eponym Lists and Chronicles | Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia | Babylonian Chronicle I | Ptolemy’s Canon | Tyrian/Sidonian Records | TMYC Dates | UPC Dates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCL 2013; Millard 1994; Thiele 1951, 287–292; Rawlinson 1862a, 1862b, 1867 | Luckenbill 1926, 1927 | Grayson 2000; Pinches 1887 | Depuydt 1995, 98; Thiele 1951, 293–294 | Cross 1972, 17; Whiston 1737, Josephus, Against Apion, Bk 1, §17–18 | Beckman 2021, Supplement 1–6 | Pierce 2001, Addendum 5–6; Ussher 1658, §464 –465 | ||

| Solomon—last king of Israel over a united kingdom; reign calculated working back 40 years from Rehoboam’s accession | ||||||||

| 1 |

Solomon 1 Kings 5:1–18, 6:1 |

Additional sources and methods for dating Solomon’s fourth year to 968t are found in tables 6 and 7. |

Hiram Hirom/Eirōmos 980–947 B.C. |

Solomon’s fourth 968t2/967n1 | Solomon’s fourth 1012 B.C. | |||

| Hiram’s reign must overlap Solomon’s. Phoenician kings are identified with both Tyre and Sidon (1 Kings 5:1, 6). | ||||||||

| Ahab—eighth king in Israel in the divided kingdom; his last year forms an anchor date in the TMYC | ||||||||

| 2 |

Ahab 1 Kings 16:31 |

Shalmaneser III Shulman-asharidu 859–824 B.C. | Battle of Qarqar 853 B.C. | Jezebel was the daughter of Ethbaal (1 Kings 16:31). |

Ethbaal Ithobalus/Ithobalos 879–847 B.C. |

Ahab’s reign 874n–853n | Ahab’s reign 918–897 B.C. | |

|

Ahab’s reign must overlap Shalmaneser’s sixth at the Battle of Qarqar and some part of Ethbaal’s

(his father-in-law). “Karkar . . . I destroyed . . . 10,000 soldiers of Ahab, the Israelite” Kurkh Stela (Monolith Inscription), Luckenbill 1926, §594, 610–611 |

||||||||

| Ahaziah and Jehoram/Joram—the two kings of Israel who ruled between Ahab and Jehu | ||||||||

| 3 | Ahaziah’s two-year reign (1 Kings 22:51) and Jehoram/Joram’s 12-year reign (2 Kings 3:1) must have been recorded by non-accession reckoning to fit within the 12-year period between Ahab and Jehu. | |||||||

| Jehu—eleventh king in Israel in the divided kingdom; his accession year forms an anchor date in the TMYC | ||||||||

| 4 |

Jehu 2 Kings 9:1–8 |

Shalmaneser III Shulman-asharidu 859–824 B.C. |

Eighteenth year tribute 841 B.C. |

Marble Slab Inscription (Safar 1951, below) provides independent corroboration. |

Balazeros Ba’li-ma-An-zeri 847–841 B.C. |

Jehu’s reign 841n–814n |

Jehu’s reign 884–857 B.C. |

|

|

Shalmaneser’s records for his eighteenth year claim tribute from Jehu and Balazeros, so the kings’

reigns must overlap. Assyrian records link Jehu to Omri, father of Ahab (§2 above; 1 Kings 16:29)

and grandfather of Ahaziah and J(eh)oram (§3 above). Since Jehu wiped out Ahab’s line (2 Kings

9–10), it is unclear whether Assyrian records intended to identify Jehu as a “successor” or a “son”

in the line of kingship.

“Tribute of Iaua (Jehu), son of Omri (mâr Humrî)” Black Obelisk Luckenbill 1926, §553–554, 590 “In my eighteenth year . . . I received the tribute of the men of Tyre, Sidon and of Jehu, son of Omri” Annals Luckenbill 1926, §671–672 “In my eighteenth pale . . . The tribute of Ba’li-ma-An-zeri, the Tyrians, (and) of Jehu the son of Omri, I received.” Safar 1951, 18–19 |

||||||||

| The overlap of Assyrian Eponym records with Ptolemy’s king list, and the astronomical data in both, confirm the reign dates | ||||||||

| 5 | Genesis 1:14–19 |

Solar Eclipse 763 B.C. |

The king lists overlap from 747–648 B.C. | Nabonassar Era Eclipses | Assyrian Sargon II’s reign in Babylon |

Anchors 853, 841 B.C. |

Anchor 562 B.C. |

|

| Ptolemy (second c AD) precisely linked astronomical observations to the year of a king’s reign, and these have been checked by modern astronomers. In the overlap between the Assyrian and Ptolemaic lists, the Assyrian king Sargon II took the throne in Babylon in 709 B.C. That date becomes the anchor from which to work backward to 763 B.C., a year in which a solar eclipse was noted in the Assyrian record, which is confirmed as accurate by modern astronomers (Thiele 1951, 46–48). | ||||||||

| Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III was also called Pul in historical documents | ||||||||

| 6a | 1 Chronicles 5:26 |

In Assyria 745–727 B.C. |

Inscriptions in Luckenbill 1926, 269–296 §761–827 |

Tiglath-pileser In Assyria 745–727 B.C. |

Babylonian throne, two kings combined, Ukinzer and Pulu/Poros, 732–727 B.C. | In the Incirli Stela (below), the Assyrian king identifies himself by both names. | ||

|

In Babylon 729–727 B.C. |

In Babylon Ukinzer 732–729 B.C. Tiglath-pileser 729–727 B.C. |

|||||||

|

Against Damascus (Syria) 733–732 B.C. |

||||||||

| Tiglath-pileser III is Pul: 1 Chronicles 5:26 uses a singular verb and pronoun for the king of two names, with an epexegetical waw between the names to read ‘Pul, that is, Tiglath-pileser’ (Steinmann 2011, 177, footnote 257; Thiele 1951, 76–77); a Babylonian king list with parallels to Babylonian Chronicle I lists Pulu in the same space of time that Tiglath-pileser ruled in Babylon (Thiele 1951, 76–77); the Incirli Stela, found in 1993, lists the king by both names, “This frontier region is the gift of Tiglath-Pilesar, Puwal, King of Assyria” (Kaufman 2007, 15). | ||||||||

| Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III mentions interactions with two kings of Judah and three kings of Israel | ||||||||

| 6b |

Various kings 2 Kings 16:1–9 2 Chronicles 28:16–21 2 Kings 15:19 2 Kings 15:29–30 |

Tiglath-pileser III Assyrian reign 745–727 B.C. Against Syria 733–732 B.C. |

Azariah/ Uzziah Ahaz Menahem Pekah Hoshea |

Assyrian throne 745 B.C. Babylonian 729 B.C. Death 727 B.C. |

Babylonian throne, Ukinzer and Pulu/Poros 732–727 B.C. |

Azariah/Uzziah Ahaz Menahem Pekah Hoshea |

791–740t 736–716t 752–742n 752–732n 732–723n |

811–759 B.C. 743–727 B.C. 772–762 B.C. 760–740 B.C. 731–721 B.C. |

|

•“Azariah, the land of Judah . . . which had gone over to Azariah in revolt (lit., sin) and contempt of Assyria” Luckenbill 1926, §770 •“The tribute of . . . Iauhazi (Jehoahaz [Ahaz]) of Judah” Luckenbill 1926, §801 and 2 Kings 16:1–9, 2 Chronicles 28:16–21 •“The tribute of . . . Menihimmu (Menahem) of Samerina (Samaria)” Luckenbill 1926, §772 and 2 Kings 15:19 •Assyrian eponyms 733 and 732 B.C. each say “against the land of Damascus [Syria]” and 2 Kings 16:5–9 “Then Rezin king of Syria and Pekah the son of Remaliah, king of Israel, came up to wage war on Jerusalem, and they besieged Ahaz but could not conquer him. . . . So Ahaz sent messengers to Tiglath-pileser king of Assyria, saying, ‘I am your servant and your son. Come up and rescue me from the hand of the king of Syria and from the hand of the king of Israel, who are attacking me.’ Ahaz also took the silver and gold that was found in the house of the Lord and in the treasures of the king’s house and sent a present to the king of Assyria. And the king of Assyria listened to him. The king of Assyria marched up against Damascus and took it . . . and he killed Rezin.” •“Pakaha [Pekah], their king they deposed and I placed Ausi’ (Hoshea) over them as king” Luckenbill 1926, §816 and 2 Kings 15:29 “In the days of Pekah king of Israel, Tiglath-pileser king of Assyria came . . . and he carried the people captive to Assyria” and 2 Kings 15:30 “Then Hoshea the son of Elah made a conspiracy against Pekah the son of Remaliah and struck him down and put him to death and reigned in his place, in the twentieth year of Jotham the son of Uzziah” |

||||||||

| Assyrian king Shalmaneser V conquered Israel and its capital city, Samaria | ||||||||

| 7 | 2 Kings 17:3–6, 18:9–11 |

Shalmaneser V 727–722 B.C. |

725–723 B.C. against . . . | 723 B.C. ravaged Samaria |

Ululai 727–722 B.C. |

Fall of Samaria and Israel | 724t2/723n1 | 721 B.C. |

| For the years 725–723 B.C., the Assyrian Eponym List has Shalmaneser V against a place that cannot be clearly read due to damage, but Babylonian Chronicle I states that in 723 B.C., he “destroyed Sabara’in” (Pinches 1887) or “ravaged Samaria” (Grayson 2000). Shalmaneser V is the only Assyrian king named in the account of 2 Kings 17:3–6, 18:9–11, for example, “In the fourth year of King Hezekiah, which was the seventh year of Hoshea son of Elah, king of Israel, Shalmaneser king of Assyria came up against Samaria and besieged it, and at the end of three years he took it.” The three years of the Assyrian Eponym List correspond to the three years of siege in 2 Kings 17:3–6, 18:9–11 (Thiele 1944, 173), and fall within Shalmaneser’s/Ululai’s reign according to Ptolemy’s Canon (Thiele 1951, 77, 293). | ||||||||

| Assyrian king Sargon II is listed according to his Babylonian reign in both the Assyrian Eponym List and Ptolemy’s Canon | ||||||||

| 8a | Isaiah 20:1 |

Sargon II Eponym 719 B.C. Throne in Babylon 709 B.C. |

Sargon II accession Assyria 722n Babylonia 710n |

Sargon II In Babylonia, first official year in 709 B.C. | ||||

| According to Babylonian Chronicle I, when Shalmaneser V died in the tenth month (December/January) of 722n, Sargon II took the throne in Assyria, and shortly after in the month of Nisan (721n, 721 B.C.), Merodach-baladan (§9 below) took the throne in Babylon. | ||||||||

| Beginning with Sargon II, the Assyrian Eponym List no longer provides a clear accounting of the Assyrian reign lengths of the kings, but it does indicate that Sargon took the throne in Babylon in 709 B.C. This matches the record of Ptolemy’s Canon, which lists Sargon’s first year as king of Babylon in 709 B.C. Similarly, Babylonian Chronicle I states that Sargon ascended the throne in Babylon in 710n (710–709 B.C.), which would have made his first official year 709n (starting in 709 B.C.). This overlap between the records, along with astronomical data (§5 above), confirms the reliability of the dates listed in these sources. | ||||||||

| Assyrian king Sargon II claimed to have conquered Samaria during his rule | ||||||||

| 8b | Although Sargon II took credit for the capture of Samaria as part of his reign, the combined evidence of the Assyrian Eponym List, Babylonian Chronicle I, and the Bible attributes this to Shalmaneser V (Thiele 1951, 77, 293). Further, Sargon II did not make the claim in early records during his reign, only in those that appeared much later (Thiele 1951, 123–128). | |||||||

| Assyrian king Sargon II was the first to drive Babylonian king Merodach-baladan into hiding | ||||||||

| 8c | Babylonian Chronicle I explains that in 710n, Sargon went to Akkad (Babylonia), fought Merodach-baladan, and drove him out. This is confirmed by Ptolemy’s Canon, which shows the end of the reign of Merodach-baladan (Marduk-appal-iddin) in 710 B.C. and the first official year of Sargon’s reign in 709 B.C. (§9a below). | |||||||

| Assyrian king Sargon II establishes the date of a prophecy against Egypt and Cush according to Isaiah 20:1 | ||||||||

| 8d | Isaiah 20:1 “In the year that the commander in chief, who was sent by Sargon the king of Assyria, came to Ashdod and fought against it and captured it—” Sargon II ascended the throne in Assyria in 722n (table 4), and in year 11 of his reign he captured Ashdod (Luckenbill 1927, §29-30), so that 722n - 11 = 711n (likely within 711 B.C.) marks the date of Isaiah’s prophecy (Steinmann 2011, 348). | |||||||

| Babylonian king Merodach-baladan (in exile) evaded Assyrian kings Sargon II and Sennacherib during their reigns | ||||||||

| 9a |

Hezekiah 2 Kings 18–20; 2 Chronicles 32; Isaiah 36–39 |

Sennacherib pursued Merodach-baladan in first campaign (703n, or 703– 702 B.C.) and fourth campaign (700n) | First official year 721 B.C., ousted 710 B.C.; second reign in 703n |

Merodach-baladan in Babylon 721–710 B.C. |

Merodach-baladan called Marduk-apla-iddina or Marduk-appal-iddin |

Hezekiah 729t coreg 716t sole 687t end |

Hezekiah 728 B.C. coreg 727 B.C. sole 699 B.C. end |

|

|

Sargon II’s ‘year 12’ records (Luckenbill 1927, §31–38) agree with Babylonian Chronicle I,

describing Merodach-baladan’s retreat in 710n. Sennacherib’s ‘first campaign’ records (Luckenbill

1927, §234, 256–263, 270–273, 301) also agree with Babylonian Chronicle I concerning the retreat of

703n, and Sennacherib’s ‘fourth campaign’ records (Luckenbill 1927, §242–243, 313– 315) describe

Merodach-baladan’s retreat in 700n and Sennacherib’s subsequent installment of his son

Assur-nadin-shum on the Babylonian throne. Date confirmation comes from Ur where texts list the

twenty-second year of the exiled king, 722 B.C. accession - 22 = 700 B.C. (Brinkman 1964, 16).

According to Babylonian Chronicle I, Merodach-baladan (Marduk-apla-iddina II) took the throne in Babylon after the death of Shalmaneser V (Ululai/Iloulaios in Ptolemy’s Canon) in 722n, and twice fled before Assyrian kings, first in 710n, when Sargon II attacked Akkad (Babylonia) in Merodach-baladan’s twelfth year and then took the throne himself, and then in 703n, in Sennacherib’s second year (705n - 2 = 703n) when the Assyrian king installed a ruler in Babylon of his own choosing (Bel-ibni, whose accession year is 703n, whose first official year—also listed in Ptolemy’s Canon—is 702n). Brinkman (1964, 13, footnote 44) aptly describes Merodach-baladan’s pattern of behavior, saying “Merodach-Baladan exhibited a decided propensity during the reigns of both Sargon and Sennacherib to avoid any direct military conflict with the main Assyrian army.” |

||||||||

| Babylonian king Merodach-baladan sent envoys to Hezekiah after Assyrian king Sennacherib’s invasion of Judah | ||||||||

| 9b | The Bible says: 1) Hezekiah reigned for 29 years (2 Kings 18:1–2; 2 Chronicles 29:1), 2) Sennacherib invaded Judah in the fourteenth year of Hezekiah’s reign (2 Kings 18:13; Isaiah 36:1), and 3) when Hezekiah became gravely ill, God promised to extend his life by 15 years (2 Kings 20:6; Isaiah 38:5–6). Thiele realized that these passages placed Hezekiah’s illness at the same time as Sennacherib’s invasion (1951, 156). In the TMYC, Hezekiah’s fourteenth year is 716t - 14 = 702t. Sennacherib’s Prism places his third campaign in 701n. These two records overlap in 702t2/701n1. Also in the TMYC, Hezekiah died in 687t, so his illness occurred in 687t + 15 = 702t, meaning his illness was within the same six-month timeframe. Right after Hezekiah’s recovery, Merodach-baladan sent envoys to him (2 Kings 20:12; Isaiah 39:1), so this visit could have easily come in 701 B.C. or 700 B.C., when Merodach-baladan was still alive according to Sennacherib’s records (§9a above). | |||||||

| Assyrian king Sennacherib invaded Judah in the fourteenth year of the reign of Hezekiah of Judah | ||||||||

| 10 |

Hezekiah 2 Kings 18:13; Isaiah 36:1 |

702 B.C.— eponym year for Bellino Cylinder 700 B.C.— eponym year for Rassam Cylinder 689 B.C.— eponym year for Oriental Institute Prism |

Third campaign in Judah (Luckenbill 1927, §240, 311–312, 347); dated 701 B.C., between Bellino and Rassam Cylinders | In Assyria, first official year (year 1) 704n [implies 705n accession]; killed in 681n (in the eighth year of no king or an unnamed king in Babylon) | Sennacherib not named; in 689 B.C. ruined Babylon; first interregnum = first official year in 704 B.C.; final year second inter-regnum = 681 B.C. |

Invasion 702t2/701n1 Sennacherib death 681 B.C. Hezekiah 729t coreg 716t sole 687t end |

Invasion 714 and 711 B.C. Sennacherib death 711 B.C. Hezekiah 728 B.C. coreg 727 B.C. sole 699 B.C. end |

|

Also, in 2003, Young located another anchor date for the TMYC that landed during Solomon’s reign, when the Jewish people were still united as a single nation. Thiele had worked backwards from his anchor dates to set the start of the divided kingdom in 931n on the Israelite side (Thiele 1944, 144–147). Young made a small correction to the start of the divided kingdom on the Judean side, placing it in 932t2/931n1 (second half of the Tishri year, first half of the Nisan year, six months running from spring to fall in 931 B.C.; Young 2003, 590–591). In so doing, Young was able to determine that Solomon began to build the temple in Jerusalem in 968t2 (Young 2003, 599–603). That anchor date will also be included in comparing the dates devised by the UPC to those of the TMYC.

Each of the three TMYC anchor dates—968t for Solomon starting the temple, 853n for the last year of the reign of Ahab of Israel, and 841n for the year that Jehu took the throne in Israel—are more than 40 years later in history than the equivalent UPC dates—1012 B.C. for Solomon starting the temple (Ussher 1658, §465), 897 B.C. for the end of Ahab’s reign (Pierce 2001, Addendum 5), and 884 B.C. for the start of Jehu’s (Pierce 2001, Addendum 6). So which chronology best fits Scripture and the combined testimony of other historical records?

Jehu’s Accession Year—841n or 884 B.C.?

Pierce’s opening statement in this section is technically incorrect because he says, “This date is documented on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III” (2001, 63). The Black Obelisk does not offer the date that Jehu brought tribute to Shalmaneser; it simply identifies him as a tributary and, famously, depicts Jehu face down on his hands and knees before the Assyrian king. Two separate Assyrian records provide the year of this event, 841 B.C.; one is an annals fragment and the other is the Marble Slab Inscription (table 5, §4). The latter piece provides yet another cross-check, because it mentions that the Phoenician king Balazeros brought tribute in the same year. Balazeros’ years of reign can be calculated from records preserved by Josephus, and his rule also overlaps 841 B.C. (table 5, §4).

Shalmaneser III predates the kings listed in Ptolemy’s Canon, so how did archaeologists discover when he ruled in Assyria? His reign is listed in a set of manuscripts collectively called the Assyrian Eponym List which, as mentioned before, overlaps Ptolemy’s Canon (table 4), specifically from 747–648 B.C. As an astronomer, Ptolemy correlated his king list with astronomical events like lunar eclipses, and modern astronomers can calculate, according to our current dating system, when these events occurred. Further, they can also confirm that they align with each particular year to which they are assigned in a given king’s reign, along with the time spans between these celestial events.

When comparing the Assyrian Eponym List to Ptolemy’s Canon, Assyrian king Sargon II appears in both with a notation that he assumed the throne in Babylon in 709 B.C. Working backward through each year on the Assyrian list, the year 763 B.C. is assigned as the one in which a solar eclipse occurred, and modern astronomers can confirm it by their calculations (table 5, §5). So Shalmaneser III’s dates of reign, with 859 B.C. as his accession year, 853 B.C. as his sixth year, and 841 B.C. as his eighteenth, appear to be reliable, and this was the process traced by Thiele in setting his anchor dates (1951, 46–48).

Ahab’s Final Year—853n or 897 B.C.?

As just stated, dates from the Assyrian Eponym List appear to be reliable due to multiple copies of the list, the correlation of a specific year on the list to a known solar eclipse in 763 B.C., and the overlap of the list with Ptolemy’s Canon. This means the 853n date for Shalmaneser III’s sixth year, when he records a battle with Ahab, is sound. Additionally, it is possible to perform a cross-check on the dates of Ahab’s reign using the Phoenician records provided by Josephus. The Bible explains that Ahab married Jezebel, daughter of the Phoenician king Ethbaal (1 Kings 16:31). A correct chronology, then, would have an overlap between the reigns of Ethbaal and Ahab (table 5, §2). This works in the TMYC, but not in the UPC, which places Ahab’s death 18 years before Ethbaal came to the throne.

Pierce questioned whether Ahab would have had a force of the size described in Shalmaneser’s records, following the drought described in 1 Kings 17–18. However, in 1 Kings 20, God graciously gave Ahab victory in each of two Syrian invasions, so Israel could have gained chariots and other equipment at that time. Also, 1 Kings 22:1 indicates that there was a period of three years following these victories in which there was no war with Syria, so even more time was available to recover from any losses experienced in the earlier drought.

Ultimately, both of Thiele’s anchor dates, 841n for Jehu and 853n for Ahab, are confirmed by their connection to an even earlier anchor date discovered by Young in 2003. He found three different ways to confirm that the fourth year of Solomon, when he began to build the temple, was 968t2 (second half of the Tishri year, six months running from spring to fall in 967 B.C.). Since Young published after Pierce, this anchor date was not addressed in Pierce’s article, but it will be covered in the next section in order to further support the interconnectivity and soundness of the TMYC dates.

New Discovery: Solomon’s Fourth Year and the Start of the Temple—968t2/967n1 or 1012 B.C.?

One of the temple date confirmation methods examined by Young had already been published as early as 1953 (Liver). It used the Tyrian records preserved by Josephus in Against Apion (Whiston 1737, Bk 1, §17–18) to determine the dates of the reign of Hiram (table 6, left column). This date calculation had been published even earlier by a Belgian professor and priest named Valerius Coucke in 1925 and 1928, but not in English (Young 2010, 225, footnote 1). Thiele acknowledged some of the agreement between his chronology and Coucke’s, but did not describe the manner in which Coucke derived the same date for the start of the temple (Thiele 1944, 143). That was left to Young who—after fellow chronologist Andrew Steinmann obtained a copy of Coucke’s 1928 work—published both an English translation of Coucke’s calculations and an article examining it (Young 2010). Further, Young discovered Coucke had also cross-checked the temple date with older historical data prior to the time of Hiram and Solomon, moving forward in time to reach the same date for the temple from a different direction in history (table 6, right column).

| From events after the temple: | From events before the temple: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 753 B.C. | Founding of Rome Marcus Terentius Varro, first c B.C. (Sanders 1908, 316, 319–320) |

1207 B.C. | Fall of Troy (Young 2010*) Parian Marble, third c B.C. (Newing 2001*; Rotstein 2016*) |

||||

|

+72 825 B.C. |

Founding of Carthage 72 years before Rome Marcus Junianus Justinus, third c A.D. (Watson 1853, Bk 18, Sec 6) |

+1 1208 B.C. |

Building of Tyre 1 year before Troy’s fall Marcus Junianus Justinus, third c A.D. (Watson 1853, Bk 18, Sec 3) |

||||

|

825 B.C. + 155 -12 968 B.C. 825 B.C. +143 968 B.C. |

Founding of Carthage Hirom/Hiram began reign 155 years earlier Solomon began temple in Hiram’s twelfth year Founding of Carthage Solomon began temple 143 years earlier Flavius Josephus, first c A.D. (Whiston 1737, Against Apion, Bk 1, §17–18) |

1208 B.C. -240 968 B.C. |

Building of Tyre 240 years from Tyre to the temple Flavius Josephus, first c A.D. (Whiston 1737, Antiquities, Bk 8, Ch 3, §1) |

||||

| 1 Kings 5:1–18 “Now Hiram king of Tyre sent his servants to Solomon when he heard that they had anointed him king in place of his father, for Hiram always loved David. And Solomon sent word to Hiram, . . . ‘I intend to build a house for the name of the Lord my God. . . . Now therefore command that cedars of Lebanon be cut for me. And my servants will join your servants, and I will pay you for your servants such wages as you set, for you know that there is no one among us who knows how to cut timber like the Sidonians.’ . . . So Solomon’s builders and Hiram’s builders and the men of Gebal did the cutting and prepared the timber and the stone to build the house.” | |||||||

| UPC dates: 1013 B.C. Hiram and Solomon made arrangements (Ussher 1658, §464); 1012 B.C. Solomon begins to build the temple (Ussher 1658, §465) | |||||||

| TMYC dates: 969t–968t Hiram and Solomon made arrangements (Young 2010); 968t Solomon begins to build the temple (Young 2003) | |||||||

| *There is a one year date difference between the fall of Troy as calculated by Coucke and by other modern translators. Young provides a thorough explanation in Young (Coucke Translation) 2010, 3–4, footnote 5. | |||||||

The third method of confirming the temple date was published by Young in 2003. Part of what makes it such a remarkable discovery is that it uses Scripture extensively to show how two calendar systems employed within the Bible—counting years by sabbaticals and jubilees and marking time by kings’ reigns—tie together precisely and corroborate one another (table 7).

| Nisan half-year | Tishri half-year | Month(s) included | Event | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 605n1 | 606t2 | mos 1-6 | Nebuchadnezzar has a decisive victory in the Battle of Carchemish and becomes king in Babylon (accession year) in 605n according to Babylonian Chronicle V | These events date Nebuchadnezzar’s accession and Daniel’s captivity (Parker and Dubberstein 1956, 27; Wiseman 1956, 67–69) |

|

Jehoiakim accession 609t Per Daniel 609t - 3 = 606t Per Jeremiah 609t - (4-1) = 606t |

||||

|

Daniel 1:1–2, 5, 18-19, 2:1, 25 “In the third year [accession reckoning] of the reign of Jehoiakim king of Judah, Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon came to Jerusalem and besieged it. And the Lord gave Jehoiakim king of Judah into his hand. . . . [Daniel and others] were to be educated for three years [Nebuchadnezzar’s accession year, plus years 1 and 2 of reign], and at the end of that time they were to stand before the king. . . . At the end of the time, when the king had commanded that they should be brought in, the chief of the eunuchs brought them in before Nebuchadnezzar. And the king spoke with them, and among all of them none was found like Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah. Therefore they stood before the king. . . . In the second year [accession reckoning] of the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, Nebuchadnezzar had dreams; his spirit was troubled, and his sleep left him. . . . Then Arioch brought in Daniel before the king in haste and said thus to him: ‘I have found among the exiles from Judah a man who will make known to the king the interpretation.’”

Jeremiah 46:2, 25:1 “About Egypt. Concerning the army of Pharaoh Neco, king of Egypt, which was by the river Euphrates at Carchemish and which Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon defeated in the fourth year [non-accession] of Jehoiakim the son of Josiah, king of Judah . . . The word that came to Jeremiah concerning all the people of Judah, in the fourth year [non-accession] of Jehoiakim the son of Josiah, king of Judah (that was the first year [non-accession] of Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon),” |

||||

|

- 7 years 598n2 |

twelfth month is in 598t1 in 597 B.C. | fall 598 B.C. to spring 597 B.C., mos 7-12 | Nebuchadnezzar takes an unnamed Judean king captive in the Babylonian king’s seventh year, twelfth month, second day (March, 597 B.C.) according to Babylonian Chronicle V | This event dates Jehoiachin’s and Ezekiel’s captivity (Parker and Dubberstein 1956, 27; Wiseman 1956, 73) |

| 605n - (8-1) = 598n2/598t1 | ||||

|

2 Kings 24:10–12 “At that time the servants of Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon came up to Jerusalem,

and the city was besieged. And Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon came to the city while his servants

were besieging it, and Jehoiachin the king of Judah gave himself up to the king of Babylon, himself

and his mother and his servants and his officials and his palace officials. The king of Babylon took

him prisoner in the eighth year [non-accession reckoning] of his [Nebuchadnezzar’s] reign”

Jeremiah 51:64, 52:28 “Thus far are the words of Jeremiah [what follows was not written by Jeremiah]. . . . This is the number of the people whom Nebuchadnezzar carried away captive: in the seventh year [accession reckoning], 3,023 Judeans” 2 Chronicles 36:9–10 “Jehoiachin . . . reigned three months and ten days in Jerusalem. . . . In the spring of the year [Babylonian records indicate March] King Nebuchadnezzar sent and brought him to Babylon . . . and made his brother Zedekiah king over Judah and Jerusalem.” |

||||

|

Jerusalem 588t2/587n1 |

- (25-1) 574t1 |

month 7 in 574 B.C. | Ezekiel dates a vision to the start of a jubilee year in the seventh month of the twenty-fifth year of his and king Jehoiachin’s exile (fourteenth year after Jerusalem’s destruction) | When the beginning of the year, Rosh Hashanah, is on the tenth of the month, Yom Kippur, it is a jubilee year (Talmud third–eighth c A.D., Arakhin 12a, §7) |

| 588t - 14 = 574t (from city’s fall) | ||||

|

Ezekiel 40:1 “In the twenty-fifth year of our exile, at the beginning of the year [Rosh Hashanah],

on the tenth day of the month [Yom Kippur], in the fourteenth year after the city was struck down,

on that very day, the hand of the Lord was upon me, and he brought me to the city.

Leviticus 25:20–22 (sabbaticals) “‘What shall we eat in the seventh year, if we may not sow or gather in our crop?’ I will command my blessing on you in the sixth year, so that it will produce a crop sufficient for three years. When you sow in the eighth year, you will be eating some of the old crop; you shall eat the old until the ninth year, when its crop arrives.” 7n1/6t2 (mos 1–6) is ordinary and harvesting permitted in sixth year; 7n2/7t1 (mos 7–12) is first half of sabbatical year; 8n1/7t2 (mos 1-6) is second half of sabbatical year; 8n2/8t1 (mos 7–12) is ordinary and sowing permitted in eighth year; 9n1/8t2 (mos 1-6) is ordinary and produces harvest in ninth year (Steinmann 2011, 29–30) Leviticus 25:8–12 (jubilees) “You shall count . . . seven times seven years . . . forty-nine years. . . . on the tenth day of the seventh month. On the Day of Atonement . . . the fiftieth year . . . shall be a jubilee for you, when each of you shall return to his property and each of you shall return to his clan. That fiftieth year shall be a jubilee for you; in it you shall neither sow nor reap what grows of itself nor gather the grapes from the undressed vines. For it is a jubilee. It shall be holy to you. You may eat the produce of the field.” 49n1/48t2 (mos 1–6) is ordinary and harvest goes to temporary landholder; 49n2/49t1 (mos 7–12) is first half of sabbatical/jubilee year, starting in the forty-ninth year; 50n1/49t2 (mos 1–6) is second half of sabbatical/jubilee year, in the 50th Nisan year; 50n2/50t1 (mos 7–12) is ordinary and sowing permitted for original landowner back in possession of their land and the crops that it will produce (Steinmann 2011, 30–36) |

||||

| Nisan year count began in 1406n |

574t +[(49x17) -1] 1406t |

month 1 of 1406 B.C. | Ezekiel’s jubilee was the seventeenth since the Hebrews had entered Canaan | Talmud third–eighth c A.D., Arakhin 12b, §5 |

| Joshua 4:19—“The people came up out of the Jordan on the tenth day of the first month” | ||||

|

+ 40 1446n |

month 1 of 1446 B.C. | The Hebrews left Egypt 40 years prior to entering Canaan | Wilderness wandering | |

|

Deuteronomy 8:2 “And you shall remember the whole way that the Lord your God has led you these forty

years in the wilderness” (and also Exodus 16:35; Numbers 14:33–34, 32:13; Deuteronomy 2:7, 8:4,

29:5; Nehemiah 9:21; Psalm 95:10; Amos 2:10, 5:25; Acts 7:36, 42, 13:18; Hebrews 3:9, 17 [Steinmann

2011, 50])

Exodus 12:2, 13:3–4 “This month shall be for you the beginning of months. It shall be the first month of the year for you. . . . Then Moses said to the people, “Remember this day in which you came out from Egypt. . . . Today, in the month of Abib [later called Nisan], you are going out.” |

||||

|

- (480-1) 967n1 |

972t-4 968t2 |

month 2 | Solomon began building the temple in his fourth year and in the four-hundred and eightieth year since the Hebrews left Egypt | 932t Solomon’s death (Young 2003) + 40 (1 Kings 11:42) - 4 = 968t |

| 1 Kings 6:1 “In the four hundred and eightieth year after the people of Israel came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month, he began to build the house of the Lord.” | ||||

In one calendar system, sabbatical and jubilee years, Young located an anchor date from Nebuchadnezzar’s attack on Jerusalem in 598n2/598t1, which took place in March, 597 B.C. This date is set by Babylonian Chronicle V (Wiseman 1956, 67–73) which assigns the event to Nebuchadnezzar’s seventh year, in the twelfth month, on the second day, and can be converted by the Parker and Dubberstein date tables (1956, 1942) into the Nisan, Tishri, and B.C. year dating systems. At this time, both Jehoiachin king of Judah and the prophet Ezekiel were taken captive. Later, in Ezekiel 40:1, the prophet dates a vision to the twenty-fifth year of his exile and the start of a jubilee year. The twenty-fifth year of exile is calculated by the formula 598t - (25-1) = 574t. Rabbis compiling the Talmud realized that Ezekiel was also identifying the start of a jubilee year, stating, “Which is the year when the beginning of the year is on the tenth of the month? You must say that this is referring to the Jubilee, which begins on Yom Kippur, the tenth of Tishrei” (Talmud Arakhin 12a §7). God had commanded the Israelites to start counting years for sabbaticals and jubilees once they entered Canaan. It seems that a record had been kept, because there was also a tradition in the Talmud that this jubilee mentioned by Ezekiel was the seventeenth (Talmud Arakhin 12b §5). The ordinary years were counted by Nisan years, and a sabbatical or jubilee would start at the halfway point, in Tishri, of the seventh and forty-ninth years, respectively. Accordingly, the calculation for when the Hebrews entered Canaan is 574t + [(49 × 17)-1] = 1406t. The first year of the count began in the springtime month of Nisan (then called Abib/Aviv or “the first month”), which was the same month they crossed the Jordan River into Canaan (Joshua 4:19), so the people came into the land in 1406n, or 1406 B.C. in modern calendar terms.

In the other calendar system, kings’ reigns, Young worked backward from Thiele’s anchor dates for Ahab and Jehu to the start of the divided kingdom with Rehoboam’s reign in Judah and Jeroboam I’s reign in Israel. The start of Rehoboam’s reign coincides with the death of Solomon at the end of Solomon’s 40-year reign (1 Kings 11:42–43; 2 Chronicles 9:30–31). Young made a small correction to Thiele’s chronology, setting the start of Rehoboam’s reign in 932t, not 931t. Thiele had worked backward in time from anchor dates for Ahab and Jehu in Israel where Nisan years were used, and established that Jeroboam I began his reign in 931n. But Thiele did not explain what methodology he used to decide which overlapping Tishri year would apply to Rehoboam, 932t2/931n1 or 931t1/931n2. Young determined that it was 932t2/931n1, or 932t. From this point, Young could determine the fourth year of Solomon, when he started the temple according to 1 Kings 6:1, by the formula 932t + 40 - 4 = 968t. However, 1 Kings 6:1 points out that this was in the second month, which fell in 968t2/967n1, or 967 B.C. since the first half of a Nisan year (containing months 1–6) runs from spring to fall. Then 1 Kings 6:1 can be used to determine the date of the exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt, because the temple was started in the four hundred and eightieth year counting from that event. The formula is 967n + (480-1) = 1446n. Because the Israelites had left Egypt in Nisan (Exodus 12:2, 13:4; where it is called Abib/Aviv or “the first month”), the date is 1446 B.C. in modern calendar terms.

All that remains to tie the two dates together, 1446 B.C. for the exodus from Egypt calculated from Solomon’s reign and the start of the temple, and 1406 B.C. for the entry to Canaan calculated from Ezekiel’s captivity and the jubilee year count, is the 40 years of wilderness wandering described in many passages of the Bible (table 7).

Sennacherib’s Invasion in Hezekiah’s Fourteenth Year—702t2/701n1 or 713 B.C.?

In his Evidentialism article, Pierce puts off the discussion of this date until the second part of his article, “Biblical considerations,” in the subsection “Third Biblical example.” This paper will follow the same order as Pierce in analyzing the date of the Assyrian king’s invasion of Judah.

Chronological Comparisons from Pierce’s Three Biblical Examples

As already stated, both the TMYC and the UPC are able to fit together the synchronizations between the kings of Israel and Judah. In the Evidentialism article, each of Pierce’s three biblical example sections cover points at which the UPC moves its dates further back in time than the TMYC, with the result that the UPC becomes increasingly disconnected from historical records that allow the relative dates in the Bible to be converted into absolute dates for biblical chronology.

Pierce’s First Biblical Example and the Azariah/Uzziah Coregency

Pierce does not accept a coregency of Azariah/Uzziah with his father Amaziah, with a net effect of adding 24 years to the combined reigns of the kings of Judah. This number of years also has to be added to Israel on the other side for balance, which is accomplished by giving Jeroboam II a sole reign of 41 years—rather than a combined 12 years of coregency plus 29 years of sole rule for a 41-year total in the TMYC—and adding a 12-year interregnum after Jeroboam II’s reign. The additional 12 years of reign for Jeroboam plus the 12-year interregnum increases Israel’s combined reigns by 24 years, keeping it even with Judah (table 8).

| UPC from Amaziah to Interregnum | TMYC from Amaziah to end of Jeroboam II | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| The UPC contains 24 more years in this time span than the TMYC. | |||

| Israel | Judah | Israel | Judah |

|

Amaziah of Judah began to reign in the second year of J(eh)oash of Israel (2 Kings 14:1) Amaziah of Judah died 15 years after J(eh)oash of Israel (2 Kings 14:17; 2 Chronicles 25:25) Azariah/Uzziah of Judah began to reign in the twenty-seventh year of Jeroboam II of Israel (2 Kings 15:1) Jeroboam II’s reign in Israel ended in the thirty-eighth year of Azariah/Uzziah of Judah (2 Kings 15:8) |

|||

|

J(eh)oash 14 sole remaining* |

Amaziah 29 sole* |

J(eh)oash 14 sole (after 2 of 16) |

Amaziah 29 sole |

|

Jeroboam II 41 sole (after 10-12 coreg) |

Azariah/Uzziah 38 sole |

Jeroboam II 29 sole (+12 coreg = 41) |

Azariah/Uzziah 14 sole (+ 24 coreg = 38) |

|

Interregnum 12 years |

|||

| 67 years | 67 years | 43 years | 43 years |

| UPC Synchronisms | TMYC Synchronisms | ||

| Israel | Judah | Israel | Judah |

|

J(eh)oash 842 B.C. coreg - 16 years = 826 B.C. death |

Amaziah 840 B.C. coreg - 29 years = 811 B.C. death |

J(eh)oash 798n sole - 16 years = 782n death |

Amaziah 797t sole - 29 years = 768t death |

|

Amaziah died 15 years after J(eh)oash 826 B.C. - 15 = 811 B.C. |

Amaziah died 15 years after J(eh)oash 782n - 15 = 767n (768t2/767n1) |

||

| *Pierce’s method is to count the start of a coregency as year 0. J(eh)oash of Israel began his coregency in 842 B.C., so 840 B.C. is his second year as well as the point at which he began his sole reign, which would continue for 14 years to reach his total 16. Amaziah began a coregency in 840 B.C. as year 0 and his sole reign the following year in 839 B.C. as year 1. In both cases, the 840 B.C. year value is subtracted from the total to get sole reign years. For J this is 16 - 2 = 14; for A it is 29 - 0 = 29. | In the TMYC, a coregency is always accounted for with non-accession reckoning, possibly because it could be arranged for the new king to start on the first day of the year. Therefore, Jeroboam II’s and Azariah’s/Uzziah’s reign totals have a “- 1” adjustment for the time span, since the year they became coregent king was considered their year 1. | ||

|

Jeroboam II 836 B.C. coreg start - 27 = 809 B.C. (≠ 811 B.C. for Azariah/Uzziah) |

Azariah/Uzziah 811 B.C. is start of sole reign because that is year of Amaziah’s death |

Jeroboam II 793n coreg - (27-1) = 767n 767n1 overlaps 768t2 |

Azariah/Uzziah 768t is start of sole reign because that is year of Amaziah’s death |

| Why the two-year difference? Pierce’s table (2001, Addendum 5) has Amaziah’s death and Uzziah’s start of reign in 811 B.C. Pierce’s ladder diagram (2001, Addendum 13) has the start of Uzziah’s sole reign, his year 0, in 811 B.C., but this lines up with the twenty-sixth year of Jeroboam II, not the twenty-seventh. Technically, the ladder diagram should show alignment with the twenty-fifth year, making the synchronization 2 years off, because Jeroboam II’s year 0 according to the table (2001, Addendum 6) is 836 B.C., but Pierce labels 836 B.C. as year 1 on the ladder diagram (2001, Addendum 11). | |||

Pierce asserts that “By all rules of exegesis, one would conclude that Uzziah was made king after the death of his father when he was 16 years old” (2001, 65), and adds “if you came to the throne when you were 16 but had been a viceroy with your father for 24 years already, you were made viceroy 8 years before you were born” (2001, 65).

The TMYC does not make the same starting assumption. Instead, Azariah/Uzziah would have been 16 years old when he began his coregency, not his sole reign, and his young age actually suggests this. Thiele asked, “Just when was it that Azariah was a mere lad only sixteen years old—at the time when his father had completed his long reign of twenty-nine years, or at some earlier period in his father’s life?” (1951, 72). Further, Thiele pointed out the unique circumstances in Judah at that time, as described in 2 Kings 14:8–14 and 2 Chronicles 25:17–24, when Azariah’s/Uzziah’s father picked a fight with the king of Israel and was defeated and taken captive. Thiele surmises that this event forced the people of Judah to appoint Azariah/Uzziah king in his father’s place while his father was in captivity.

Pierce also espouses another assumption underlying the UPC calculations: “The longer chronology consistently measures time from when a king became viceroy. This procedure is in accord with the oldest Talmudic understanding of how this was done” (Pierce 2001, 67). But it is hardly fair for Pierce to project a UPC rule onto the TMYC, and then claim that Thiele and McFall said two things that in fact they had not: “According to Thiele, McFall and others the text is incorrect [neither chronologist ever said this]. They say that it should read in the 3rd year of Jeroboam not the 27th [neither chronologist said this either]” (Pierce 2001, 65).

The TMYC sets the start of Azariah’s/Uzziah’s coregency in 791t, and the start of Jeroboam II’s coregency in 793n. So, by Pierce’s standard, Azariah/Uzziah began to reign in the third year of Jeroboam (first = 793n, second = 792n, third = 791n). But for this particular synchronization, the TMYC places the start of Azariah’s/Uzziah’s sole reign in the twenty-seventh year of Jeroboam counted from the start of Jeroboam’s coregency (table 8), and in so doing the TMYC calculations fit within the parameters of Scripture.

Assyrian records support the TMYC dates for this timeframe (table 5, §6b). Tiglath-pileser III claims Azariah/Uzziah was in revolt against him, and there is an overlap between the kings’ reigns in the TMYC, but not in the UPC.

Pierce’s Second Biblical Example, Pekah’s Rival Reign, and Hezekiah’s Coregency

Pierce goes on to address chronological calculations that stretch from Pekah’s reign in Israel to the fall of Samaria, Israel’s capital. The UPC states that Menahem, Pekahiah, and Pekah reigned sequentially in Israel. In contrast, the TMYC proposes a rival reign in which Pekah’s rule overlapped that of Menahem and Pekahiah, an idea that seems to have biblical support from Hosea 5:5 (Thiele 1983, 61, 63, 124, 130, 134, 136). The implications of Hosea 5:5 were pointed out earlier by H. J. Cook in 1964, although Young gives the clearest and most succinct explanation of the verse (Young 2018, 57):

The CSB translation is: “Israel’s arrogance testifies against them. Both Israel and Ephraim stumble because of their iniquity; even Judah will stumble with them.” In the Hebrew of this verse, “both . . . and” is expressed by the use of the waw conjunction before “Israel” and also before “Ephraim.” Waw by itself means “and,” but the double usage expresses “both . . . and.” . . . In all these instances the two items mentioned are necessarily separate entities, just as with “both . . . and” in English. . . . The grammar throughout the verse is consistent with the separateness of the two kingdoms. The verb “stumble” that applies to Ephraim and Israel is in the plural, and it is “their iniquity,” not “his iniquity.” . . . The situation is similar to the rivalry between Omri and Tibni 130 years earlier. For Pekah as well as for Omri, the synchronizations to Judah for the start of their reigns refer to their sole reign, whereas reign lengths for both are measured from the start of their rival kingdoms.

Within the time frame that concerns the final years of the kingdom of Israel, there is also an important distinction in the treatment of the synchronization found in 2 Kings 17:1, where Ahaz’s reign in Judah is connected to the reign of Hoshea, the last king in Israel before the fall of Samaria to the Assyrians. Hebrew verb tenses are not always as clear as those in English, and they depend on context for translation. Accordingly, this could allow an alternate reading for 2 Kings 17:1, such as Edmund Parker’s (1968, 130; italics are Parker’s): “In the twelfth year of Ahaz, king of Judah, Hoshea, the son of Elah, had reigned in Samaria over Israel nine years” or Leslie McFall’s (1991, 30; [brackets] are McFall’s): “In the 12th [accession] year from the coregency of Ahaz king of Judah, Hoshea the son of Elah had reigned nine [accession] years in Samaria over Israel.” This would mean that the end of Hoshea’s reign and the fall of Samaria is synchronized to two kings in Judah, to the twelfth year of Ahaz (2 Kings 17:1) and the sixth year of his son, Hezekiah (2 Kings 18:10). This also indicates that Hezekiah was in a coregency with his father at that time.

Because the UPC does not recognize a 12-year rivalry in Pekah’s reign, the time span for reigns in Israel is increased by that amount. On Judah’s side, Jotham and Ahaz are each credited with 16 years of sole reign in the UPC, rather than eight years each under the TMYC. Also, because the UPC takes the traditional interpretation of 2 Kings 17:1, Hezekiah is credited with six sole reign years until the fall of Samaria in the UPC, while the TMYC counts these years as part of a coregency. This means that on Judah’s side, the UPC time span is expanded by 8 + 8 + 6 = 22 years. Then, to bring Israel into balance, the UPC adds a nine-year interregnum and a one-year increase in Hoshea’s reign to the extra 12 years of kings’ reigns in Israel, so that 12 + 9 + 1 = 22 years. In a strange twist, these calculations make Ahaz only 10 or 11 years old when Hezekiah was conceived (table 9).

| UPC from Menahem to Samaria’s fall | TMYC from Menahem to Samaria’s fall | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| The UPC contains 22 more years in this time span than the TMYC. | |||

| Israel | Judah | Israel | Judah |

|

Menahem of Israel began to reign in the thirty-ninth year of Azariah/Uzziah of Judah (2 Kings 15:17) Pekahiah of Israel began to reign in the fiftieth year of Azariah/Uzziah of Judah (2 Kings 15:23) Pekah of Israel began to reign in the fifty-second year year of Azariah/Uzziah of Judah (2 Kings 15:27) Hoshea of Israel began his reign in the twentieth year of Jotham of Judah (2 Kings 15:30) Hoshea of Israel, based on translation of the verb tense for reign, either: • Began to reign in the twelfth year of Ahaz of Judah (2 Kings 17:1) • Ended his reign with the fall of Samaria in the twelfth year of Ahaz of Judah (2 Kings 17:1) Hoshea of Israel ended his reign and Samaria fell in his ninth year and Hezekiah’s sixth year (2 Kings 18:10) |

|||

|

Menahem 10 sole |

Azariah/Uzziah 10 years (thirty-ninth to forty-ninth years) |

Menahem 10 rival |

Azariah/Uzziah 10 years (thirty-ninth to forty-ninth years) |

|

Pekahiah 2 sole |

Azariah/Uzziah 2 years (fiftieth to fifty-first years) |

Pekahiah 2 rival |

Azariah/Uzziah 2 years (fiftieth to fifty-first years) |

|

Pekah 20 sole |

Azariah/Uzziah 1 year (fifty-second year) |

Pekah 8 sole (after 12 rival = 20 total) |

Azariah/Uzziah 1 year (fifty-second year) |

|

Interregnum 9 years |

Jotham 16 sole |

Jotham 8 sole to twentieth (or 4 sole to sixteenth) |

|

|

Hoshea 10 sole |

Ahaz (age 20–36 years old) 16 sole |

Hoshea 9 sole |

Ahaz (age 20 at Jotham’s sixteenth year) 8 sole (12 sole from Jotham’s sixteenth) |

| If Ahaz is 36 yrs old when son is 25, Ahaz became father at 11. |

Hezekiah (age 25 at start) 6 sole** (727–722 B.C.) ≠ 721 B.C. fall of Samaria |

716t (Hezekiah) + 25 = 741t (born) 736t (Ahaz age 20), 741t (Ahaz age 15) |

Hezekiah (age 25 in 716t at

start of sole) reign; began

coregency in 729t 0 sole (sync is to sixth coreg) |

| 51 years | 51 years | 29 years | 29 years |

| UPC Synchronisms | TMYC Synchronisms | ||

| Israel | Judah | Israel | Judah |

|

Hoshea #1 / interregnum 739 B.C. (Jotham’s twentieth)* Hoshea #2 / secure throne 731 B.C. (Ahaz’s twelfth) |

Jotham 759 B.C. coreg/sole - 20 years = 739 B.C. (Pierce 740 B.C.)* Ahaz 743 B.C. sole - 12 = 731 B.C. |

Death of Pekah = Hoshea’s start of reign = 732n 732n2 overlaps 732t1 |

Jotham 751t coreg - (20-1) = 732t |