The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

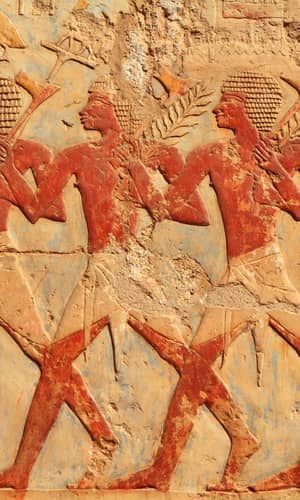

One of the most popular topics among young earth creationists and apologists is the relationship of the Bible with Ancient Egyptian chronology. Whether it concerns who the pharaoh of the Exodus was, the background of Joseph, or the identity of Shishak, many Christians (and non-Christians) have wondered how these two topics fit together. This paper deals with the question, “How does ancient Egyptian chronology correlate with the book of Genesis?” In answering this question it begins with an analysis of every Egyptian dynasty starting with the 12th Dynasty (this is where David Down places Moses) and goes back all the way to the so called “Dynasty 0.” After all the data is presented, this paper will look at the different possibilities that can be constructed concerning how long each of these dynasties lasted and how they relate to the biblical dates of the Great Flood, the Tower of Babel, and the Patriarchs.

Keywords: Egypt, pharaoh, Patriarchs, chronology, Abraham, Joseph

Introduction

During the past century some scholars have proposed new ways of dating the events of ancient history before c. 700 BC.1 In 1991 a book entitled Centuries of Darkness by Peter James and four of his colleagues shook the very foundations of ancient chronology. They proposed a 250-year reduction of the dates in the Near East and Mediterranean before c. 700 BC and this has resulted in new interpretations for ancient history and the Bible.2 The Conquest has been placed in new archaeological strata and so have the events and periods of the Exodus, the Judges, and the United Monarchy. However, not as much research has been done on how the book of Genesis fits into all of this. This paper will not only consider the question of when the Patriarchs entered and lived in Egypt but also will consider if the chronology of certain periods of early Egyptian history (Early Dynastic, Old Kingdom, First Intermediate Period, and the Middle Kingdom) need to be revised. This is important when considering the relationship between Egyptian history and the Tower of Babel. The traditional dating of Ancient Egyptian chronology places its earliest dynasties before the biblical dates of the Flood and confusion of the languages at Babel. This paper will examine if and how these early dynasties correlate with these events in Scripture. This paper begins with the assumption that David Down’s placement of the Exodus in the late Middle Kingdom and Amenemhat III as Moses’ father-in-law is correct (Down 2001).3 It will begin with the 12th Dynasty and work itself back to the earliest rulers.

The Chronology of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt

In his research David Down places the birth of Moses in the reign of Amenemhat III, who was the sixth king of the 12th Dynasty (Ashton and Down 2006; Down 2001). The exact year is unknown, but since it is unlikely that Moses was chased out of Egypt after the fall of this dynasty we can narrow down to approximately which years he would have been born.4 Amenemhat III ruled 46 years according to the archaeological record. His two successors, Amenemhat IV (whose first year is possibly the same as Amenemhat III’s 44th year)5 and Sobekneferu, ruled about 10 and 4 years respectively (Schneider 2006, pp. 173–174). Sobekneferu was the daughter of Amenemhat III and could have possibly been the adoptive mother of Moses (see Down 20013). It is assumed that Moses fled from Egypt to Midian before the 12th Dynasty ended with Sobekneferu. If we place Moses’ birth in Amenemhat III’s 13th year this would place Moses’ 40th year in Amenemhat IV’s year 10.6 If we place Moses’ birth year in Amenemhat III’s first year it would place Moses’ 40th year within his reign. It would seem unusual if Sobekneferu tried to kill Moses, her adoptive son. So this narrows down the birth of Moses to Amenemhat III’s first to 13th years.

Table 1. Twelfth Dynasty (after Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 35 and Schneider 2006)

| King’s Name | Turin Canon | Archaeological Record | |

|---|---|---|---|

1. |

Amenemhat I |

[X]9 |

30 |

2. |

Senusret I |

45 |

44 |

3. |

Amenemhat II |

10 + or 30 + [X] |

35 |

4. |

Senusret II |

19 |

8 |

5. |

Senusret III |

30 + [X] |

19/30/33/39 |

6. |

Amenemhat III |

40 + [X] |

45 for sure, probably 46 |

7. |

Amenemhat IV |

9 years 3 months 27 days |

9 for sure, maybe a year 10 |

8. |

Sobekneferu |

3 years 10 months 24 days |

Year 3 |

The next step is to determine the length of the 12th Dynasty prior to Amenemhat III’s accession. Table 1 places the kings of the 12th Dynasty into chronological order and gives the reigns of these kings according to the Turin Canon (a papyrus dating from the 19th Dynasty listing Egyptian kings) and the archaeological record (the contemporary evidence). However, there is a debate going on among Egyptologists as to whether or not co-regencies existed during the 12th Dynasty. Before it can be determined how long this dynasty lasted, these possible co-regencies must be examined.

Let’s begin with the first two kings, Amenemhat I and Senusret I. The archaeological record indicates 30 and 44 years respectively. However, one of the records (the Stele of Antef) states that Year 30 for Amenemhat I and Year 10 for Senusret I are one and the same (Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 37), indicating a co-regency between these two monarchs. This co-regency is also alluded to in the Instruction of Amenemhat (Simpson 1956, p. 215). Furthermore, year 24 of Amenemhat I is given as corresponding to a unnamed year of Senusret I in the Stela of Nesu-Montu and this same stela also refers to the kings in the dual at the beginning of the text (Simpson 1956, p. 215). Thomas Schneider also mentions that

an architrave from Matariya . . . names both kings symmetrically with their titularies and apparently as co-reigning builders; both are designated as nsw bjt and living Horus (i.e. as reigning king) (Schneider 2006, p. 171).

Adding more, Schneider mentions that

the control marks from Lisht . . . reveal that it was only in regnal year 10 of [Senusret] I that the construction of his pyramid began, i.e., apparently after the death and burial of [Amenemhat] I in his pyramid complex (Schneider 2006, p. 171).

All of these records strongly suggest that these two kings were co-regents.7

Now, for the third king of the 12th Dynasty, Amenemhat II, the archaeological record states 35 years, and he had a co-regency with both his predecessor, Senusret I, and one with his successor, Senusret II (Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 38). The Turin Canon entry for Amenemhat II is damaged in the “ones” place but shows that he ruled 30 + years. The Stele of Wepwaweto indicates that his 2nd year was the same as Year 44 of Senusret I and the Stela of Hapu equates Amenemhat’s Year 35 with Year 3 for Senusret II, the fourth king of the dynasty (Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 38).

For Senusret II, the Turin Canon says 19 years and the archaeological record says eight. Possible evidence for a reign of eight years includes:

- Extremely limited quarrying activity

- A restriction of the distribution of monuments

- Few major officials known from his reign (Simpson 1984)

This data seems to point to a short reign but it must be noted that just because the evidence is scanty for his rule does not provide proof that he ruled for only eight years and the Turin Canon’s 19 years may be correct (more on this below).

For the fifth king, Senusret III, we have a number of possibilities. The Turin Canon credits him with at least 30 years (the entry being damaged in the “ones” position); however, the highest the archaeological record goes is 19 years. There are, nevertheless, other records that may indicate a longer reign for him. In 1990 a record was discovered that strongly indicates Senusret III reached Year 30, “but the king’s name isn’t mentioned in the writing, and the argument is based on the context” (Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 40). There is also a possible Year 39 marker, but again the name of the pharaoh is not mentioned. However, Josef Wegner has given evidence that Senusret III did in fact reach a Year 39 and that there was a co-regency between him and his successor Amenemhat III. His evidence includes:

- The Year 39 marker was found in a context that belongs to Senusret III and not in the context of Amenemhat III as some believe. This context was Senusret’s mortuary temple and was built to possibly be his burial place. This would be strange if the marker indicated Year 39 for Amenemhat III. Why would Amenemhat build a burial chamber for his father who died nearly 40 years earlier (Wegner 1996, p. 257)?

- The context of the find was also discovered “deep within a mass of material.” This would make the marker intrusive if it didn’t belong to Senusret. The deepness of the find makes it improbable that it is from Amenemhat (Wegner 1996, p. 260).

- The context also includes pottery that is typical of the reign of Senusret III (Wegner 1996, pp. 257– 260).

- Some statues of Senusret III show him as a young man, and some show him as an old man. This finding would be unusual if he reigned only 19 years but would make sense if he reigned almost 40 years (Wegner 1996, pp. 265–266).

- Other evidence includes co-dated offerings, co-dated monuments, and co-naming in stelae, seals, and small objects. There is also the coronation inscription of Amenemhat III being crowned before a living Senusret III (Wegner 1996, pp. 270–274).

Now the above five points by themselves do not prove a co-regency but, taken together, they seem to imply rather strongly that these two pharaohs ruled at the same time for at least awhile (Year 1 of Amenmhat III equals Year 20 of Senusret III).

Before we move on to the 11th Dynasty some comments must be made concerning the discrepancy between the Turin Canon and the archaeological data regarding the length of Senusret II’s reign. The Turin Canon is remarkably close to the archaeological records for five8 out of the eight rulers of the 12th Dynasty, and it is probably close for two others.9 The only king for whom the Turin Canon has a clear discrepancy with the contemporary data is for Senusret II. Sensuret II has only eight years recorded in the archaeological data but 19 years in the Turin Canon. Years 9–19 are not extant in the contemporary records, but that does not mean they did not exist; there is also the possibility that the Turin Canon is wrong here.

In an effort to evaluate the conflicting claims for Senusret II’s reign, the archeological records carry much weight with this writer. The three points made above concerning the limited documentation from Senusret II’s reign is strong evidence for a short reign. For Senusret II to have extremely limited quarrying activity, little distribution of monuments, and few officials known from his reign is very odd in a dynasty of kings for whom documentation is generally well preserved. For all three of these to be lacking for one king is strange.

There is a possible explanation to consider for the Turin Canon’s reading. Concerning the 19 years recorded for Sensuret II in the Turin Canon, the list may be wrong because the large number of co-regencies in the dynasty may have confused the author of the list. The 19 years is how long Senusret III, his successor, ruled by himself and since the Canon has 30+ years for Senusret III on the next line, the writer may have erroneously thought that the 19 belonged to his predecessor, Senusret II. Another reason some ascribe the 19 years to Senusret II is that the Illahun papyri indicates that a Year 19 of a king is directly followed by a Year 1 of another king; however, since some scholars do not agree with a co-regency between Senusret III and Amenemhat III, they naturally think that the 19 years must belong to Senusret II (Wegner 1996, p. 267). After reviewing the five points described above in evidence for this co-regency, it seems clear that Senusret III and Amenemhat III did overlap by many years, allowing the “Year 19/Year 1” papyri to apply to them rather than to Senusret II. Thus, while we cannot be dogmatic as to the length of Sensuret II’s reign, the shorter 8-year reign is strongly supportable.

In conclusion, the evidence is in favor of a number of co-regencies during the 12th Dynasty. It can be seen that the length of this dynasty before Amenemhat III was 121–132 years, depending on whether Senusret II ruled for eight or 19 years. Table 2 (in the last column) indicates this.

Table 2. Length of Twelfth Dynasty before Amenemhe III with co-regencies (after Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 40)

| Total Length of Reign | Co-regency with Successor | Total Years Before Start of Successor | |

|---|---|---|---|

Amenemhat I |

30 |

10 |

20 |

Senusret I |

44 (45?) |

2(3?) |

42 |

Amenemhat II |

35 |

3 |

32 |

Senusret II |

8 or 19 |

8 or 19 |

|

Senusret III |

39 |

19 |

The Eleventh Dynasty (see Table 3)

Next, as we count back through Egyptian history, we come to the 11th Dynasty. The Turin Canon claims 143 years for this dynasty. This writer for now will assume that this number is correct for a couple of different reasons. First, where the evidence is preserved in the archaeological record for the 11th Dynasty kings, the Turin Canon’s data matches up quite nicely. It is, of course, not perfect since the archaeological record is incomplete but where the evidence is available the contemporary records do not contradict the Turin Canon.

Second, one possible piece of evidence can be taken from Manetho. Manetho records 43 years for the 11th Dynasty but “that the ‘hundreds’ figure dropped out in transmission is not an unreasonable resolution of this inconsistency” (Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 52). Now this is not, of course, the greatest amount of evidence but it is something that should be considered when determining the length of this dynasty.

One last thing to consider for the 11th Dynasty concerns possible co-regencies. The Turin Canon does not acknowledge the co-regencies of the 12th Dynasty; therefore, if any existed during the eleventh, the list probably would not have acknowledged them either. The current lack of evidence for co-regencies in the 11th Dynasty does not conclusively prove none existed. For now, given the agreement between the Turin Canon and the archeological records, this paper will assign 143 years to the 11th Dynasty.

Table 3. The Eleventh Dynasty

| King’s Name | Years (in Turin Canon) |

Archaeological Data (Seidlmayer 2006b, p. 160) |

|---|---|---|

Mentuhotep I |

||

Intef I |

16 |

|

Intef II |

49 |

Year 50 (probably year of burial) |

Intef III |

8 |

|

Mentuhotep II |

51 |

Year 46 |

Mentuhotep III |

12 |

Year 8 |

Mentuhotep IVi |

7 |

Year 2 |

Total |

143 |

106 |

i This name does not appear in the Turin Canon but he is known to exist through archaeological evidence.

First Intermediate Period

The 11th Dynasty king Mentuhotep II reunited Egypt sometime during his reign. Before his time Egypt is believed to have consisted of two kingdoms: one in the north (9th and 10th Dynasties) and one in the south (11th Dynasty). The 7th and 8th Dynasties are also included in this era. This period is known as the First Intermediate Period (FIP), thought to be a time of chaos but about which little is actually known.

The FIP’s chronology is confusing. Records for the 7th–10th Dynasties and the 11th Dynasty before Mentuhotep II are both scanty and conflicting. There are varying accounts regarding the northern kings, the 9th and 10th Dynasties ruling from Herakleopolis, recorded in the Turin Canon and Manetho’s writings. Manetho states that the 9th Dynasty consisted of four kings ruling for 100 years (according to Eusebius’ quotations from Manetho) or 19 kings who ruled 409 years (according to Africanus’ version of Manetho), these widely discrepant records being unverifiable since Manetho’s original writings are not extant.10 Both Eusebius and Africanus record that Manetho has 19 kings for 185 years for the 10th Dynasty. The Turin Canon has only 18 kings for both the 9th and 10th Dynasties; however, almost all the names and all the reign lengths are missing.

Before the 9th–11th Dynasties, most of the pharaohs, including those of the 7th and 8th Dynasties, ruled from Memphis. For these two earlier dynasties (which are part of the FIP) the Manetho sources are even more confusing: Africanus records that the 7th Dynasty had 70 kings who ruled for 70 days in all and that the 8th Dynasty had 27 kings who reigned for 146 years. Eusebius says that the 7th Dynasty had five kings who ruled for 75 days total and that the 8th Dynasty had five kings who ruled for 100 years.

There are a number of different ways that scholars date the kings of the FIP. The first way is that of most Egyptologists. These scholars have a different layout for this period than does Manetho. As one can see from Table 4, Egyptologists date the northern Herakleopolitans as starting after the 8th Dynasty had ended and start the southern 11th Dynasty about 35–38 years later. However, the archaeological data for the chronology for the 9th and 10th Dynasties is lost, and the c. 35–38 years for the advent of the 11th Dynasty is just a guess. Chronological data for the 7th and 8th Dynasties is also lost for the most part and their chronological relationship to the other dynasties of the FIP is just a guess.

Table 4. Traditional chronology for the Sixth–Eleventh Dynasties (through Mentuhotep II); all dates are BC

| Dynasties | Shaw 2002, p. 480 | Hornung, Krauss, and Warburton 2006, p. 491 |

|---|---|---|

|

6th Dynasty

|

2345–2181

|

2305–2150

|

|

7th and 8th

|

Dynasties 2181–2160

|

2150–2118

|

|

9th and 10th

|

Dynasties 2160–2025

|

2118–1980

|

|

11th Dynasty (before Mentuhotep II)

|

2125–2055

|

2080–2009

|

|

Mentuhotep II

|

2055–2004

|

2009–1959

|

The 9th and 10th Dynasties are believed to have been contemporary with the 11th Dynasty until Mentuhotep II of the 11th Dynasty united Egypt. Although the exact timing is unknown, he united the northern and southern kingdoms sometime between his 14th and 41st years (Seidlmayer 2006b, pp. 162–163). Therefore, his unification of Egypt occurred sometime between 87 and 114 years after the beginning of the 11th Dynasty.

Prior to the unification of Egypt under the 11th Dynasty, there are several questions that need to be answered. First of all, although it is generally thought that the Herakleopolitan dynasties (9th and 10th) began to rule before the 11th Dynasty started, we need to determine when. Secondly, the placement of the 7th and 8th Dynasties needs to be clarified. For instance, how do scholars come to the conclusion that the 7th and 8th Dynasties ruled for about 21–32 years before the 9th and 10th Dynasties existed? And how is it known that Dynasty 11 came to power about 35–38 years after the Herakleopolitans came to power?

To find these answers, another aspect of this period needs to be examined. There were many local rulers/dynasties ruling in Upper Egypt (the southern Nile region) during the early part of the FIP (that is, before Dynasty 11). In fact, most of the information concerning this time comes from the tombs of these local dynasts. Why do these local rulers matter? Well, it is these local rulers that scholars use to determine the accepted chronology of the early FIP. Seidlmayer (2006b, pp. 166–167) suggests that the period between the 8th and 11th Dynasties must be long because of several generations of local rulers/administrators in each town in Upper Egypt between these dynasties. However, most information for these local rulers is (as mentioned above) from their graves, and nothing says exactly how long the period is. A long time-frame between the end of Dynasty 6 and the beginning of Dynasty 11 is based only on assumptions about average generation lengths and partly on Manetho’s 185 years for his 10th Dynasty. Seidlmayer plainly states that

of course, there is no way to be sure about the correctness of Manetho’s figure; if one chooses to disregard Manetho’s data, however, the length of the Herakleopolitan dynasty becomes entirely a matter of speculation (Seidlmayer 2006b, p. 166).

As mentioned, scholars use average generation lengths to help them determine the length of the period, but do these really help? These do not work as well as many would hope since an average generation can be different throughout history; furthermore, local political and economic circumstances can effect how likely it is for a single king (or governor or other leader) to rule. For instance, during civil war or economic hardship it may be more likely for a country to go through many more rulers than normal, whereas during a time of peace and economic prosperity a ruler would not have as many rivals as during hard times. A royal family’s inheritable health issues, for instance, not allowing them to live as long as others (or possibly vice versa) could have an impact on average generation length. An average generation is usually thought to be about 20–40 years depending upon the scholar or ancient source. However, history shows many exceptions. One example is the 13th Dynasty, which according to Hornung, Krauss, and Warburton (2006, p. 492), had 12 rulers in just c. 129 years, an average of 10.75 years per generation. However, the total number of rulers in the 13th Dynasty is actually uncertain. Manetho assigns it 60 kings, and the Turin Canon assigns it almost the same. Most of the reign lengths are lost, but of those that survive, most are very short (2–3 years, some a little more, and some being less than one year, with only a couple being 10 or more years). If this dynasty really did have as many kings as the Turin Canon or Manetho says, then the generation average would be only about 2–3 years for each king. Thus, generating a chronology based on an average generation is not very reliable

What are we then to do when it comes to the chronology of this period if we cannot rely on average generation lengths or Manetho? Could the early FIP have been longer or perhaps shorter? Detlef Franke when discussing the early FIP and its chronology, even admits “yet events can also accelerate, and many things can happen in a relatively short time” (Franke 2001, p. 528). Franke agrees with the idea that this period lasted for a long time and agrees with the use of average generation lengths, yet he even admits that it all could have happened in a shorter timeframe. So, is there another way to determine just how long this period lasted?

Table 5. Sixth–Eighth Dynasty kings at Memphis (after Beckerath 1962, p. 143; Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 147–148 and Ryholt 2000, p. 99)

| King’s Name | Manetho Name | Turin Canon | Manetho | High Year Mark | Saqqara King List | Abydos King List | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1.

|

Teti

|

Othoes

|

Lost

|

30

|

11th count

|

X

|

X

|

|

2.

|

Userkare

|

—

|

Lost

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

3.

|

Pepi I

|

Phius

|

20

|

53

|

25th cattle count

|

X

|

X

|

|

4.

|

Merenre I

|

Methusuphis

|

14 or 44

|

7

|

Year after fifth cattle count

|

X

|

X

|

|

5.

|

Pepi II

(Neferkare I) |

Phiops

|

90 + X

|

94

|

Year after 31st cattle count

|

X

|

X

|

|

6.

|

Merenre II

|

Menthusuphis

|

1

|

1

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

7.

|

Netjerkare

(Nitocris) Siptah |

Nitocris

|

Lost

|

12

|

X

|

||

|

8.

|

Menkare

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

9.

|

Neferkare

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

10.

|

Neferkare Neby

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

11.

|

Djedkare Shemai

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

12.

|

Neferkare Khendu

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

13.

|

Merenhor

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

14.

|

Neferkamin

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

15.

|

Nikare

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

16.

|

Neferkare Tereru

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

17.

|

Neferkahor

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

18.

|

Neferkare Pepi-Sonb

|

—

|

Lost

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

19.

|

Neferkamin Anu

|

—

|

Lost

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

20.

|

Qakaure Ibi

|

—

|

2 years 1 month

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

21.

|

Neferkaure

|

—

|

4 years 2 months

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

22.

|

Neferkauhor Chui (?)

|

—

|

2 years 1 month 1 day

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

|

|

23.

|

Neferirkare II

|

—

|

1 year

|

—

|

—

|

X

|

Table 5 sets forth the kings of the 6th–8th Dynasties as set forth in Manetho, the Turin Canon, the Saqqara King List, and the Abydos King List.11 (These last two lists do not give how many years each king ruled, so the X indicates that the particular pharaoh is in the list.)

The above table illustrates for us an important point. Out of the four lists (Turin Canon, Manetho, Saqqara, and Abydos) we have a completely different listing of kings for this period. Abydos has many more kings than all the others while the Table of Saqqara has only four kings. The Turin Canon agrees with the Abydos list as to a king between Teti and Pepi I while Manetho agrees with the Saqqara list by omitting this king, as if he never existed.

Another observation evident from these lists (not indicated in the table) is that both the Saqqara and the Abydos lists omit all the kings of the Herakleopolitans and all the 11th Dynasty kings before Mentuhotep II, who unified Egypt and brought the FIP to an end. Furthermore, there is no archaeological data to pinpoint when the Memphite kings of the 7th and 8th Dynasties came to an end relative to the ascension of the Herakleopoltian kings. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Shaw 2002, p. 480) gives only 21 years for the 7th and 8th Dynasties (24 years if we include Nitocris) as does the Cambridge Ancient History (Edwards et al 1971, p. 995). Hornung, Krauss, and Warburton (2006, p. 491) give 32 years for this same time period. The 21–32 years are based on little to no evidence and are just a guess.

There have been four ways to interpret the chronology of the FIP. The first is mentioned above and is accepted by most scholars (that is, c. 21–32 year period for the 7th and 8th Dynasties followed by c. 35–38 year period for the 9th and 10th Dynasties prior to the rise of the 11th Dynasty). The second way to interpret the chronology is what is accepted by J. V. Beckerath (1962, pp. 146–147). He believes that the 9th and 10th Dynasties followed the 8th Dynasty but that there was never a time when the Herakleopolitans ruled all of Egypt; instead, he contends that the 11th Dynasty began to rule Upper Egypt at the exact same time as the 9th Dynasty began. A third interpretation is that given by David Down. Down ends Dynasty 6 about halfway between the Middle Kingdom (11th and 12th Dynasties) and he places the 7th–11th Dynasties to the Second Intermediate Period. The fourth way to determine the chronology of this time is based on the arguments of Gary Greenberg. He believes that each king list has its own point of view concerning this period:

While most Egyptologists tend to dismiss the differences among the Turin Canon, Table of [Saqqara], and the Table of Abydos as reflecting the chaotic nature of the First Intermediate Period . . . a more logical interpretation is that these king lists each presents a different political-theological viewpoint about the legitimacy of various kings. The Egyptians were a very conservative people and did not approve of abrupt changes in the political order. The populous saw the king as a human manifestation of the Egyptian god Horus. A challenge to the legitimate king was the equivalent of a challenge to the Horus. During the First Intermediate Period . . . there were possibly three rival kingdoms, Memphis, Thebes, and [Herakleopolis]. Only one could be the legitimate center of power. Horus could only rule from one throne. The central theological problem of the First Intermediate Period, then, was: “When did Horus stop ruling in Memphis and when did he begin to rule from another city?” The three king lists, I suggest, present three different viewpoints, each based on political-theological viewpoints (Greenberg 2003–2004, pp. 154–155).

The first list, the Saqqara, according to Greenberg,

Suggests a “plague on all your houses” point of view. Implying that the outbreak of troubles began either during or immediately after the reign of [Pepi] II, the fourth king (in the [Saqqara] and Manetho lists) of the Sixth Dynasty, the [Saqqara] scribe refuses to recognize any legitimate authority until [Mentuhotep II] reunited Egypt (Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 155).

Therefore, the Table of Saqqara omits the entire time that there were competing kings in different parts of Egypt. This shows that there would be a short period of overlap between the Memphites and the Herakleopolitans, unlike what most Egyptologists claim. It is also possible that the Herakleopolitans began during the tail end of the reign of Pepi II.

The second king list, the Abydos,

Presents a very different perspective, that of the Memphite loyalist. What we see reflected here is definitive support for the Memphite throne, complete rejection of the Herakleopolitan claims, and some distaste for the Theban upstarts. It is only after the Memphite throne has ceased to exist and [Mentuhotep II] reunited Egypt that the Abydos scribe confers legitimacy on the Theban monarchy. If any Theban kings ruled between the time that the Memphite line ended and [Mentuhotep II] reunited Egypt, the Abydos scribe refuses to recognize their authority (Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 155).

Now we come to the Turin Canon. This list is

a Theban document, written by a Theban scribe during a Theban administration. It presents a Theban point of view. Therefore, it begins the Eleventh Dynasty with the founders of the Theban line rather with the later reign of [Mentuhotep II]. But the Thebans can not allow a document to show Memphite kings on the throne at the same time as Theban kings. This would be sacrilege, an affront to Horus in Memphis. This raises the question of whether the Memphite line ended before Thebes came to the throne or after. The Turin Canon, however, only has twelve kings listed where the Abydos list has twenty-two. Since Thebes had an interest in showing a smooth transition from Memphis to Thebes, with no gaps, I suggest that the Turin Canon’s Sixth Dynasty ended at exactly the point where it began the Eleventh Dynasty and that the Thebans deliberately omitted the last nine or ten Memphite kings in order to avoid any appearance of conflict. On the other hand, the Turin Canon does show a line of Herakleopolitan kings. This is politically significant. Theban authority stems from its defeat of the Herakleopolitan kings. Therefore the Herakleopolitan kings need to be mentioned. But the inclusion of the Herakleopolitan kings also serves to remind Egyptians that the Memphites couldn’t defeat the Herakleopolitans, and that Horus must have abandoned Memphis in favor of those kings who did defeat the Herakleopolitans. If this analysis is correct, we can date the end of the Turin Canon’s Sixth Dynasty to the start of the Eleventh Dynasty, and link the Old Kingdom’s chronology to that of the Middle Kingdom’s (Greenberg 2003–2004, pp. 155–156).

Thus Greenberg believes that the 11th Dynasty started before the Memphite kings came to an end and the Herakleopolitans started to rule right after the reign of Pepi II or even during the last part of his reign. If this is true then Pepi II’s reign ended not too long before the 11th Dynasty began.

However, there is a problem with Greenberg’s interpretation. There is a chance that the extra rulers in the Abydos List did not come after the seven rulers in the Turin Canon but ruled in between them. The Turin Canon has a six-year lacuna between Nitocris (#7 in Table 5) and Neferkare Pepi-Sonb (#18 in Table 5). Both Ryholt (2000, pp. 96–98) and Beckerath (1962, p. 145) believe that it was in this six-year period that the extra kings in the Abydos List ruled.

The reasons why the Turin Canon left these extra Abydos kings out are unknown, but there are a few possibilities. The first is that these kings were so weak the author of the Turin Canon believed they were an embarrassment to Egypt, thus excluding these kings. A second reason could be that these kings overlapped in some way which would go along with Greenberg’s interpretation that the king lists didn’t like reporting kings who did not rule all of Egypt or competing kings in different locations throughout Egypt.

There are, however, some important points that Greenberg makes. His analysis that each king list represents a different theological viewpoint is most interesting. This is evident since the Turin Canon includes the Herakleopolitans, and the entire 11th Dynasty and the Saqqara List omits every king between Pepi II and the reunification of Egypt under Mentuhotep II. Clearly, the author of the Saqqara list was dissatisfied with all of the kings in between these two benchmarks, perhaps because many of them never had complete control over all of Egypt. We should not assume that the omission implies that all of these rulers were weak: A few of these rulers either ruled for a long time (Intef II with a 49/50 year rule) or actually began construction of a pyramid complex (Qakaure Ibi—#20 in Table 5). Thus, the idea that every king during this period was short lived or weak is definitely false.

Let us now examine the rulers of the 7th and 8th Dynasties that have chronological data preserved for them. The Turin Canon (see table 5) gives five of these rulers reign lengths but the other three are lost (not including the six-year lacuna). The lengths that are still intact add up to ten years. Some archaeological data from this time has been recovered and according to Spalinger (1994, p. 312) five year dates have been assigned to pharaohs from this time. These include:

- “Year of the Unification of the Two Lands”

- “Year of the 4th occurrence . . .”

- “Year of the Unification of the Two Lands”

- “Year (2?)12

- “Year 1”

If all of these are connected to five different pharaohs then we would have at least nine (eight?) years after Pepi II in the archaeological record (notice the year four and the regnal year four in the Turin Canon). The year 4 count shows that rulers during this time could have a length this long, so the three rulers with lost numbers could have reigned for a few years. The time between Pepi II of the 6th Dynasty and the start of the 11th Dynasty could be c. 19 years if the three kings that have lost chronological data are assigned one year a piece.

Before we move on let’s go over some potential counter arguments against this reconstruction of the FIP chronology. Some will no doubt argue against the idea that there was an overlap between the 7th and 8th Dynasties and the Herakleopolitans. Franke believes that it would be “impossible” for local dynasties in Upper Egypt to have ruled during the 8th Dynasty (Franke 2001, p. 528). One must ask the obvious: Why is this impossible? In support of this “impossibility,” Beckerath (1962, p. 144) points to the Coptos Decrees, which indicate a few 8th Dynasty kings ruling over all of Egypt. (The 7th and 8th Dynasty kings were acknowledged by those living in Coptos.)

However, there are some problems with this. First, just because a king claims he ruled over all of Egypt (or someone else claims that he did) does not mean he really did. Intef III of the 11th Dynasty was said to have been King of Upper and Lower Egypt by Prince Ideni of Abydos, but it is known that he ruled only in Upper Egypt (Hayes 1971, p. 478). Second, even Beckerath, (1962, p. 144) when referring to the unified land under the 7th–8th Dynasties, says that the nomarchs during these dynasties were nearly independent (he says “nearly independent” because of his belief in these two dynasties ruling all of Egypt). Why then is it so hard to imagine local rulers in Herakleopolis gaining power locally (for it is uncertain if they ever ruled all of Egypt)? For most of the 7th and 8th Dynasty kings in the Turin Canon and the Abydos King List we have only their names and practically nothing concerning events during their reigns. Thus, there is no evidence that they ruled all of Egypt; local rulers could have carved up Egypt while the kings from Memphis (7th and 8th Dynasties) were ruling a small section of the north. One last thing to consider here is the possibility of shifting geographic spheres of influence: there may have been times when some 7th and 8th Dynasty rulers ruled much of Egypt while the Herakleopolitans ruled only their own city but other times when the power shifted, leaving the 7th and 8th Dynasties to rule only their city while the Herakleopolitans were able to reign over the bulk of Egypt.

It is also possible that some of these local rulers were contemporary with the last part of Pepi II’s reign. The last part of the reign of Pepi II is very poorly documented, and, as Greenberg mentioned above, the Table of Saqqara could point to an interpretation that the 9th and 10th Dynasties began at the tail end of the Pepi II’s rule.

There is no evidence contradicting the idea of a short period between the end of Pepi II’s reign and the start of the 11th Dynasty. Although it cannot be proven true, the king lists seem to imply that this period was shorter than what modern scholars believe.

This revised chronology of the FIP shows about 19 years for the 7th and 8th Dynasties instead of the standard 24–32 years. This chronology also removes the 35–38 years of the 9th–10th Dynasties in the standard chronology. It thus reduces the period by a total of about 40–51 years.

The Old Kingdom

Now we come to the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom (Dynasties 4–6).13 Before we proceed we must look at how these kings are dated. The pharaohs of this period used a census to date the years of their reign that is referred to as a cattle count system (like what we saw above with the last Memphite kings before the 11th Dynasty). For example a document may say something like “in the year of the sixth cattle count” or “the year after the eighth cattle count.” As it can be seen this system dates years of and after each census and because of this Sir Alan Gardiner (1945) made the assumption that each census was taken every other year; thus taking the highest known year and doubling it should correspond to how long the pharaoh ruled. Taking the above example “the year of the 6th cattle count” would be the 11th year. It is 11 years and not 12 years because the first cattle count was in year one of a particular king. “The year after the 8th cattle count” would be year 16 of that king. This method has been used every since the time of Gardiner and has been assumed to be valid.

However, a new study shows that the reign lengths of these kings may be inflated and that the cattle count system was more annual/irregular than biennial as previously believed. In his phenomenal paper, Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology, Miroslav Verner examines every single cattle count from the 4th and 5th Dynasties and makes the conclusion that they were not regularly biennial and the chronology of the Old Kingdom must therefore be reduced. He shows that “year of the counts” appears about two and a half times more often in the archaeological record than does “year after the counts.” An example of this would be the reign of Snefru, who ruled in the 4th Dynasty. Records from his reign show that the workers of his pyramids used “year of the counts” much more often than they did “year after the counts” while working on them. If the biennial system was in use, were his builders only working every other year? This may indicate that the census was more often done annually and only occasionally was biennial. We shall now look at every cattle count for each Old Kingdom pharaoh to see how long each ruled. This will allow us to see if the traditional chronology should be reduced.

The Fourth Dynasty (see Table 6)

The 4th Dynasty included the builders of the pyramids of Giza and the Great Sphinx. When it comes to its chronology there is disagreement between the ancient king lists as to how many kings ruled at this time. The Turin Canon has eight and possibly even nine kings depending on how many of them are placed between Khafra and Menkaure (two of the pyramid builders). The space for this time is badly damaged and some scholars believe that two kings could fit here (Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 185).

The Saqqara List has nine kings but places them in a different order from the Turin Canon. The two kings between Khafra and Menkaure are instead placed after Menkaure with two other minor kings. The Abydos List has only six kings with only one king after Menkaure and no break between Khafra and Menkaure. Manetho has eight kings with no break between Khafra and Menkaure. To make things even worse a discovery in the Wady Hammamat of an inscription about these kings is incomplete but has two kings after Khafra; however, Menkaure is not one of them (Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 185). The 4th Dynasty sequence of kings is in a confusing state, but the dynasty had at least six kings and there may have been three additional kings ruling for only a few days or months (or maybe not at all).

Table 6. Chronology of the Fourth Dynasty

| King’s Name | Modern (Shaw 2002, p. 480) |

Turin Canon | Manetho | Highest “Year of The Cattle Count” |

Highest “Year after The Cattle Count” |

Ratio of Cattle Counts | Ireegular | Biennial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Snefru

|

24

|

24

|

29

|

24th

|

18th

|

12/3

|

27

|

46

|

|

Khufu

|

23

|

23

|

63

|

12th

|

13th

|

5/1

|

14

|

26

|

|

Djedefra

|

8

|

8

|

25

|

11th (10?)

|

—

|

2/0

|

11

|

21

|

|

Khafra

|

26

|

Lost

|

66

|

13th

|

5th

|

6/2

|

15

|

25

|

|

Hardjedef

|

—

|

Lost

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

||

|

Bicheris

|

—

|

?

|

22

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

||

|

Menkaure

|

29

|

18 (28?)

|

63

|

11th

|

11th (?)

|

2/3

|

14

|

22

|

|

Shepseskaf

|

5

|

4

|

7

|

1st

|

1st

|

1/1

|

2

|

2

|

|

Thamphthis

|

—

|

2

|

9

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

||

|

Queen Khentkaus I

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

||

|

Total

|

119

|

79 (89?)

+ x |

284

|

83

|

142

|

Snefru

Snefru was the founder of the 4th Dynasty. He ruled for 24 years according to the Turin Canon and 29 years according to Manetho. The highest preserved date for him is the year of the 24th count. He has twelve “year of the counts” preserved but only three “year after the counts” (Spalinger 1994, pp. 281–283; Verner 2001, pp. 365–368; Verner 2006, pp. 128–131).14

As it can be seen there is a great disproportion between the number of “year of the counts” and “year after the counts” for his reign. Verner notes (2001, p. 369) that the inscriptions concerning the building of the pyramid at Meidum contain marks that are only “year of the count.” This would imply that the pyramid was worked on every two years if the counts were biennial. Why would the work crews only work on a funerary monument so important to their pharaoh (thought to be a god in human form) every two years? This does not make since if the cattle counts were taken every other year but if they were irregular then the large amount of “year of the counts” would make perfect since.

If the counts are irregular then this would mean that Snefru reigned for at least 27 years since there are three “year after the counts” for his reign (note that the Turin Canon has 24 years while Manetho has 29 years). If the counts were biennial he would have ruled 46 years.15

Khufu

Khufu, the second king, is perhaps one of the most famous rulers in history since he is the builder of the Great Pyramid at Giza. The Turin Canon allots him 23 years while Manetho gives him 63 years. There are five “year of the counts” preserved for his reign16 with only one “year after the count” (Spalinger 1994, pp. 283–285; Verner 2001, pp. 372–373; Verner 2006, pp. 131–132).17 The highest count from his reign is the “year after the 13th count” making his reign at least 14 years or 26 years (irregular or biennial respectively).

Djedefra

The third king of this dynasty was Djedefra. He is given eight years and 25 years in the Turin Canon and Manetho respectively. There are two “year of the counts” available from his reign; the highest being the 11th year.18 However, there are no “year after the counts” known from his reign so this makes his rule at least 11 years or 21 years (Verner 2001, pp. 374–375; Verner 2006, p. 132).19

Khafra

Khafra is the next king of this dynasty. He was the builder of the second largest pyramid and the Great Sphinx at Giza. His reign length is lost in the Turin Canon; however, Manetho gives him 66 years. Six “year of the counts” have been discovered with the 13th year as the highest; only two “year after the counts” are known. This would make his reign at least 15 or 25 years long (Spalinger 1994, pp. 286–288; Verner 2001, pp. 377–379; Verner 2006, pp. 133–134).20

Hardjedef (?) and Bicheris/Rabaef (?)

The period between Khafra and Menkaure (see below for this king) has been a challenge to Egyptologists. As mentioned above some sources put one or two kings in this place. The names of these possible kings are said to be Hardjedef and Rabaef (Greenberg 2003–2004, p. 184). These names are based on the Wadi Hammamat inscription already mentioned but Manetho (who has just one king extra king) gives the name Bicheris. Whether or not the Turin Canon has one or two kings is a matter of debate. Some archaeologists say that one of these kings may have built the Great Pit in Zawiyet el-Aryan but this is one of the least known of all the monuments in the pyramid fields (Verner 2001, p. 380). The pit is an unfinished substructure of a pyramid and the king’s name associated with it has caused major difficulties in interpretation. Verner (2001, p. 380) states that the copies of the inscriptions are unreliable and were hand sketches and not facsimili. Smith (1971, p. 176) believes that only a few months are required for this king (if he ruled at all; see below).

One of Egypt’s princes, Sekhemkare (Khafra’s son), “records that he was honored by [Khafra], [Menkaure], Shepseskaf, Userkaf, and Sahure” (Smith 1971, p. 176). This statement omits both of our mystery kings and even Thamphthis (the last king of the 4th Dynasty; see below). Other officials21 show no evidence for these three kings (including Thamphthis) as well. Either these three kings ruled very briefly (days, weeks, or a few months) or they never ruled at all. Donald Redford brings some insight into this mystery by arguing that the Egyptians themselves believed that these kings (Hardjedef and Rabaef) ruled because they were sons of Khufu, so there may have been an erroneous belief that all of Khufu’s sons (Redford 1986, p. 237) ruled.

On the other hand, the name associated with the Great Pit is in a cartouche (Verner 1997, p. 241; Verner 2001, pp. 380–384), as is the other name between Khafra and Menkaure suggesting they actually did rule. The evidence seems strong that they must have ruled. However, it seems that this is for a very short period, probably a few weeks or months.

Menkaure

Menkaure, the builder of the smallest of the three pyramids at Giza, is our next king to examine. The Turin Canon has 18 or 28 years while Manetho has 63 years. Only two “year of the counts” are known while there are three “year after the counts.” The highest count is the “year after the 11th count.” This would make his reign at least 14 years or 22 years (Spalinger 1994, pp. 288–291; Verner 2001, p. 382; Verner 2006, pp. 134–135).22

Shepseskaf

King Shepseskaf ruled for four or seven years according to the Turin Canon and Manetho respectively. Only two counts have been preserved: the “year of the 1st count” and the “year after the 1st count” making his rule at least two years long (Spalinger 1994, pp. 291–292; Verner 2001, p. 383; Verner 2006, pp. 135–136).

Thamphthis

The last king of the 4th Dynasty is named Thamphthis by Manetho and he gives this king nine years. The name is missing in the Turin Canon, but it gives this king only two years. Verner (2001, pp. 384–385) notes no census counts exist for this king. One must remember, though, that the contemporary data mentioned above with the other two mysterious kings do not acknowledge him in any way.

Queen Khentkaus I

A few remarks must be made concerning Queen Khentkaus I. She is someone who Egyptologists debate whether or not who ruled. She was the wife of Shepseskaf, and she held a title that has been translated in two different ways: “Mother of two kings of Upper and Lower Egypt” and “King of Upper and Lower Egypt and Mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt” (Verner 1997, p. 262). Some data supporting the possibility that she ruled by herself is an image of the queen that shows her with “the vulture diadem, the ritual beard, and the scepter.” However, there is more data to suggest that she did not rule. Her name is not written in a cartouche and she is not mentioned at all by contemporary sources (the same data concerning our other mysterious kings above) (Verner 1997, p. 264).

The Fifth Dynasty (see Table 7)

Userkaf

Userkaf was the first king of the 5th Dynasty. He is given seven years in the Turin Canon while Manetho gives 28 years. Only two counts are preserved for him: “year of the 3rd count” and the “year after the 1st count” (Spalinger 1994, pp. 294–296; Verner 2001, p. 386; Verner 2006, pp. 136–137). This gives him a rule of four or five years if the counts are irregular or biennial respectively.

Table 7. Chronology of the Fifth Dynasty

| King’s Name | Modern (Shaw 2002, p. 480) |

Turin Canon | Mantheo | Highest “Year of The Cattle Count” |

Highest “Year after the Cattle Count?” |

Ratio of Cattle Counts | Irregular | Biennial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Userkaf

|

7

|

7

|

28

|

3rd

|

1st

|

1/1

|

4

|

5

|

|

Sahure

|

12

|

12

|

13

|

5th

|

6th

|

4/3

|

8

|

12

|

|

Neferirkare

|

20

|

Lost

|

20

|

5th

|

—

|

1/0

|

5

|

9

|

|

Shepseskare

|

7

|

7

|

7

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Neferefra

|

3

|

X + 1

|

20

|

1st

|

—

|

1/0

|

1

|

1

|

|

Neuserre

|

24

|

[X] 1

|

44

|

7th

|

2nd

|

4(?)/1

|

8

|

13

|

|

Menkauhor

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Djedkare

|

39

|

28

|

44

|

21st (22nd?)

|

17th

|

15(?)/7(?)

|

28

|

41 (43?)

|

|

Unas

|

30

|

30

|

33

|

8th

|

4th

|

3/1

|

9

|

15

|

|

Total

|

149

|

105 + x

|

218

|

63

|

96 (98?)

|

Sahure

The second king was Sahure. He is given 12 years in the Turin Canon and 13 years by Manetho. Four “year of the counts” and three “year after” counts have been found for this king and these makes his reign eight or 12 years depending on whether the counts were irregular or biennial (Spalinger 1994, pp. 296–297; Verner 2001, p. 391; Verner 2006, pp. 137–138).23

Neferirkare and Shepseskara

Neferirkare was the third king of the 5th Dynasty. The length of his reign is missing in the Turin Canon and Manetho gives him 20 years. There is only one cattle count remaining from his reign: “year of the 5th count” (Verner 2001, p. 393; Verner 2006, p. 138). This makes his reign five or ten years long.

There are some interesting things to mention concerning Neferirkare and his successor, Shepseskara, and their reign lengths in the Turin Canon. As mentioned in this list the name and the length of reign are missing for Neferirkare. His name is known because of other sources; however, the length of his reign is thought to have been lost. The next line and king (the name is missing) is given seven years and this is given to Shepseskara since this is what he is given in Manetho. He is mentioned in the Saqqara List of kings and is not mentioned at all in the Abydos List.24

Very little contemporaneous sources are attributed to Shepseskara and none of them include year markers. There are also no buildings associated with him except for the possible unfinished platform for a pyramid halfway between Userkaf’s sun temple and Sahura’s pyramid. The state of this unfinished structure shows that work had only begun a few weeks or possibly a month or two earlier (Verner 2001, p. 399). This king seems to have ruled only for a few short weeks or months.25

With this in mind it could be possible that Shepseskara was left out of the Turin Canon like he was in the Abydos List. Verner (2001, p. 395) believes that this could mean that the 7 years of Shepseskara should be given to Neferirkare instead.

Neferefra

The fifth king of this dynasty was Neferefra. The Turin Canon gives only one year for him while Manetho gives 20 years. Verner states that

the shape of [his] tomb . . . as well as a number of other archaeological finds clearly indicate that the construction of the king’s funerary monument was interrupted, owing to the unexpectedly early death of the king (Verner 2001, p. 400).

Neither the burial apartment nor the foundation of the mortuary temple was built by the time of the king’s death. There is only one chronological marker from his reign: “year of the 1st count” (Verner 2001, p. 400).

Niuserre

The sixth pharaoh was Niuserre. The Turin Canon gives [X]1 years (the “tens” place is missing) and Manetho gives him 44 years. The cattle counts from his reign include four “year of the counts” and only one “year after the count.”26 According to these counts he ruled 8 or 13 years (Spalinger 1994, p. 298; Verner 2001, p. 402).

Menkauhor

The seventh king is Menkauhor. According to Verner (2001, p. 405) “there is no contemporaneous date that can be safely attributed to [him].” The Turin Canon gives eight years while Manetho gives nine years. Given the fact that we know that he completed his pyramid complex and that there is plenty of written evidence and other objects from his reign, Verner believes that eight years is a real possibility for this king.

Djedkara

The next king is Djedkara. The Turin Canon gives him 28 years, and Manetho has 44 years. The highest attested count is the 21st count. On a biennial census this would be 41 or 43 years. However, the “year of the counts” are represented twice as much as “year after the count” (Spalinger 1994, pp. 299–301; Verner 2001, pp. 405–408; Verner 2006, pp. 139–142).27 An irregular count would make his reign 28 years, which agrees with the Turin Canon.

Unas

The last king of the 5th Dynasty was Unas. There are three “year of the counts” and only one “year after the count.” This makes his reign nine or 15 years (Spalinger 1994, p. 301; Verner 2001, pp. 410–411; Verner 2006, pp. 142–143).28 The Turin Canon and Manetho give him a long reign of 30 and 33 years respectively.29

Further Remarks for the 4th–5th Dynasty Chronology

Now that the contemporary data and the king lists have been reviewed for the 4th and 5th Dynasties, we can now make some conclusions as to how long these dynasties lasted. First of all, let’s look at the ratio between “year of the counts” and “year after the counts.” The ratio between these is as follows:

4th Dynasty—Ratio: 28:10

5th Dynasty—Ratio: 29:13

Overall—57:23

A look at the data above shows that “year of the count” appears nearly two and a half times more than “year after the count.” Verner (2006, p. 126) maintains that the annual count prevailed with some exception during the 4th and 5th Dynasties. This conclusion is evident since many of the counts are from masons’ marks.

These short texts associated with the construction projects of the state are the most frequently preserved dated documents from [Dynasties] 4 and 5. Why should these inscriptions regularly omit every second year from the administrative record?

It is clear that when one looks at this ratio it is quite extraordinary just how many more “year of the counts” there are.

A second thing that we must look at is whether the Turin Canon supports an irregular count or a biennial count (or a little of both). Table 8 illustrates this data for us.

Table 8. Comparison of Cattle Counts with Turin Canon

| King’s Name | Minimum Reign (Irregular Count) |

30Turin Canon | Difference of Turin Canon Years Compared to Irregular Count |

Irregular or Biennial? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4th Dynasty

|

||||

|

Snefru

|

27

|

24

|

−3

|

Irregular

|

|

Khufu

(Cheops) |

14

|

23

|

+9

|

Irregular

|

|

Djedefra

|

11

|

8

|

−3

|

Irregular

|

|

Khafra

(Chephren) |

15

|

[Lost]

|

?

|

?

|

|

Menkaure

(Mycerinus) |

14

|

18

|

+4

|

Irregular

|

|

Shepseskaf

|

2

|

4

|

+2

|

?

|

|

5th Dynasty

|

||||

|

Userkaf

|

4

|

7

|

+3

|

Biennial

|

|

Sahure

|

8

|

12

|

+4

|

Biennial

|

|

Neferirkare

|

5

|

[Lost]

|

? (maybe + 2 if the 7 years in the Turin canon belongs to him and not

Shepseskare—see below)

|

Irregular

|

|

Shepseskare

|

—

|

7

|

?

|

?

|

|

Neferefra

|

1

|

X + 1

|

? (probably 0)

|

?

|

|

Neuserre

|

8

|

[X]1

|

? (probably + 3 if the number is reconstructed to “11”)

|

Irregular

|

|

Menkauhor

|

8ii

|

8

|

—

|

?

|

|

Djedkare

|

28 (29?)

|

28

|

0 (−1?)

|

Irregular

|

|

Unas

|

9

|

30

|

+21

|

Biennial

|

ii This number is taken from the Turin Canon.

Table 9. Revised chronology of the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties

| 4th Dynasty | Length of Reign | Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Snefru

|

27–29 years

|

the 29 years is taken from Manetho which is only two years more than the archaeological

record

|

|

Khufu

|

14–23 years

|

23 years is included because of the incompleteness of the archaeological record

|

|

Djedefra

|

11 years

|

|

|

Khafra

|

15 years

|

may be more but cannot be certain since Turin Canon is damaged here

|

|

Hardjedef

|

—

|

|

|

Bicheris

|

||

|

Menkaure

|

14–18 years

|

|

|

Shepseskaf

|

2–4 yedars

|

|

|

Thamphthis

|

—

|

|

|

Queen Khentkaus I

|

—

|

|

|

Total

|

83–100 years

|

|

|

5th Dynasty

|

||

|

Userkaf

|

4–7 years

|

|

|

Sahure

|

8–12 years

|

|

|

Neferirkare

|

5–7 (?) years

|

7 years may belong to him (see above)

|

|

Shepseskare

|

—

|

|

|

Neferefra

|

1 year

|

|

|

Neuserre

|

8–11 years

|

|

|

Menkauhor

|

8 years

|

the 8 years is taken from the Turin Canon

|

|

Djedkare

|

28 years

|

|

|

Unas

|

9–30 years

|

9 years is taken from the irregular count; the 30 years is from the Turin Canon and is

included for arguments sake because of the incompleteness of the archaeological record

|

|

Total

|

71–104 years

|

|

|

Overall Total

|

154–204 years

|

|

This table shows us some very interesting data. First, the Turin Canon actually has fewer years for two kings (Snefru and Djedefra). This discrepancy could indicate a co-regency or could be an error on the part of the author of the king list. However, there is a problem with the co-regency interpretation. The Turin Canon did not indicate co-regencies for the 12th Dynasty so why would it do so with other dynasties? Second, the list is in agreement in regard to possibly three kings (Neferefra, Menkauhor (?), and Djedkare). Third, the Turin Canon is within two years for possibly two kings (Shepseskaf, Neferirkare [?]) and within 3–4 years for four kings (Menkaure, Userkaf, Sahure, and Neuserre). Fourth, the list is only off by a large margin for two kings (Khufu and Unas). With Khufu the discrepancy is only nine years but with Unas, 21 years. Fifth, there are only two kings (Khafra and Shepseskare) in which the Turin Canon provides no information. (This data, however, is assuming that the seven years usually attributed to Shepseskare actually belongs to Neferirkare and that the eight years the king list gives Menkauhor is correct).

When one looks at this data between the archaeological record and the Turin Canon one will notice that if one accepts the Turin Canon’s record then in seven instances it indicates an irregular count, in three it indicates a biennial count, and in five instances we cannot draw any conclusions either because we have no chronological markers for a particular king or they ruled for such a short period of time it cannot help us indicate whether or not they used an irregular or biennial count.

In Table 9 is shown the chronology of the 4th and 5th Dynasties in their new revised state. Snefru is given 27–29 years depending upon whether or not Manetho’s figure of 29 years (which is only two years more than the 27 years in the contemporary record) is correct. Khufu is given 14–23 years and Djedefra is given 11 years. Khafra reigned about 15 years (as far as we can tell), Menkaure 14–18 years, and Shepseskaf 2–4 years. The mysterious kings, Hardjedef, Bicheris, Thamphthis, and Queen Khentkaus I are not given any years.

For the 5th Dynasty Userkaf is given 4–7 years, Sahure 8–12, and Neferirkare 5–7(?). Shepseskare is included with Hardjedef, Bicheris, and Thamphthis above and Neferefra is given only a year. Neuserre’s reign lasted 8–11 years while Menkauhor ruled eight years. The dynasty ends with Djedkare with 28 years and Unas with 9–30 years.

It should be obvious that the data we have indicates a mostly irregular count for the 4th and 5th Dynasties. When one compares the ranges in Table 9 with the standard chronologies for this period, one will notice a few interesting things. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt has 119 years for the 4th Dynasty and for the 5th Dynasty it has 149 years (Shaw 2002, p. 480). As one can see anywhere from 19–36 years needs to be shaved off of the chronology of the 4th Dynasty, while 45–78 years needs to be removed from the 5th Dynasty. That is a total of 64–114 years that the 4th and 5th Dynasties are being inflated.30

The Sixth Dynasty (see Table 10)

The annals of the 6th Dynasty kings are recorded on the South Saqqara Stone, so one may think that their reigns should be easy to calculate. However, the South Saqqara Stone was erased before it was reused in ancient times as a sarcophagus lid, and a lot of speculation is used to reconstruct it. Baud writes “that neither the demarcation of the compartments . . . nor most of the dates are preserved” (Baud 2006, p. 144).

Table 10. Chronology of the Sixth Dynasty

|

King’s Name

|

Modern

(Shaw 2002, p. 480) |

Turin Canon

|

Manetho

|

Highest “Year of The Cattle Count”

|

Highest “Year after The Cattle Count”

|

Ratio of Cattle Counts

|

Irregular

|

Biennial

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Teti

|

22

|

Lost

|

30

|

11th

|

6th

|

2/2

|

13

|

21

|

|

Userkare

|

2

|

Lost

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

|

Pepi I

|

34

|

20

|

53

|

25th

|

23rd

|

2/2

|

27

|

49

|

|

Merenre

|

9

|

14 or 44

|

7

|

5th

|

5th

|

2/2

|

7

|

10

|

|

Pepi II

|

94

|

90 + x

|

94

|

31st

|

31st

|

5/3

|

34

|

62 (65?)

|

|

Census counts not datable

|

12th

|

5th (unknown year also in existence)

|

2/2

|

|||||

|

Total

|

161

|

124–154 + x

|

184

|

83–85

|

142–147

|

Besides this, the South Saqqara Stone can not be used to reconstruct the chronology of the 6th Dynasty because too many assumptions need to be made for an accurate reconstruction. In order to reconstruct the annals one must make an assumption of whether or not the cattle counts were annual, irregular, or biennial before a reconstruction can even take place. So the stone should not be used for this purpose as we shall see as we analyze the data of each king of this dynasty.

Teti

The first king of the 6th Dynasty was Teti. Dates from his reign are not preserved on the South Saqqara Stone, and not even an estimate can be made concerning its length (Baud 2006, p. 145). Two of each type of count is known for his reign. These cattle counts indicate that he ruled at least 13 years if the counts were irregular or possibly as many as 21 years if the counts were biennial (Baud 2006, p. 146; Spalinger 1994, p. 303).31

Userkare

The Turin Canon includes a king named Userkare between Teti and Pepi I. His reign length is missing; he is not mentioned by Manetho and very little has been found concerning him in the archaeological record. Baud (2006, p. 146) mentions this is “mostly seal impressions” and also mentions that “the silence of contemporaneous private biographies is disturbing.” The Abydos King List also includes this king but the Saqqara List (not to be confused with the South Saqqara Stone) omits him. Smith (1971, p. 191) says he “seems to have had an ephemeral reign.”

However, recent research has shown that Userkare may have reigned for a few years. The South Saqqara Stone has a section for him, but practically nothing remains of it. Baud (2006, pp. 146, 156) gives him two to four years, but this is just an estimate based upon speculation. Baud says (2006, pp. 146) that

the available space between the titularies of Teti and Pepi I [on the South Saqqara Stone], when compared to the size of an average year compartment of the latter, indicates that Userkare’s reign must have been brief, from two to four years.

So we see that the reign of Userkare is based upon the assumption that his compartments are the same as Pepi I’s compartments. But we can’t be sure about this.

Pepi I

The third king of the 6th Dynasty was Pepi I. Like Teti, he has two of each type of count preserved from his reign. According to these counts he ruled at least 27 years if the count was irregular but as many as 49 years if it was biennial (Baud 2006, p. 148; Spalinger 1994, pp. 303–304).32 Baud (2006, pp. 147–151) believes that during his reign the count was biennial, but this is based upon theoretical assumptions about the South Saqqara Stone. Almost the entire portion concerning Pepi I is missing on the tablet, but Baud makes assumptions concerning the size of each compartment. He believes that, since both kinds of cattle counts are known from the king’s reign, that each formula (introducing and marking years of the king’s reign on the tablet) must contain a “year of the count” and “year after the count.” However, this is not preserved on the stone and is thus only an assumption. This belief by Baud would assume that every compartment detailing each individual year (or two years) on the South Saqqara Stone would be the same size; however, Baud mentions that some compartments are much larger than others so his conclusion of each formula covering two years (“a year of the count” and “year after the count”) is not certain.

Merenre I

The next king is Merenre. There are only two counts preserved on the annals: the two concerning the first count and year after the first count. The number of compartments for his reign on the annals is not known. “Year of” and the “year after” the fifth count are also preserved in the archaeological record (Baud 2006, pp. 151–152). According to this data, he ruled anywhere from seven years (irregular count) to ten years (biennial count).

Pepi II

Now we need to examine the reign of Pepi II. Pepi II’s reign is not recorded on the South Saqqara Stone (it was written during his reign). He has five “year of the counts” and three “year after the counts” available for his reign (Baud 2006, pp. 152–153; Spalinger 1994, pp. 307–308).33 He ruled at least 34 years if his counts were irregular, but if the counts were biennial then the number could be 62 years. The Turin Canon has him ruling 90+ years and Manetho 94 years.

Other data

There are also cattle counts which are hard to place within the reigns of this dynasty. These include:

- “Year of the count”—2nd, 12th

- “Year after the count”—5th, unknown year (Baud 2006, pp. 145, 153)

The above data cannot be securely dated but the 12th count is placed in Pepi II’s reign by Baud (2006, p. 153).

One important piece of information concerning this dynasty that needs to be mentioned is two possible co-regencies. There is evidence that may suggest that Merenre was co-regent with one or both Pepis. For Pepi II we have “a cylinder seal of an official with both of their names enclosed in a double Horus-frame” (Smith 1971, p. 193). We also have objects that suggest a co-regency with Pepi I. These include

a gold-skirt-pendant in Cairo which bears the names and titles of the two kings. The other is the Hieraconpolis copper statue-group which shows [Pepi I] with a smaller figure beside him that probably represents Merenre (Smith 1971, p. 192).

However, there have been arguments made against this data as referring to co-regencies. For the alleged co-regency between Merenre and Pepi II the seal “is inconclusive, since this piece may simply commemorate the owner’s service under both kings” (Murnane 1977, p. 227). As for the evidence for a co-regency between Pepi I and Merenre, the statue-group has been interpreted not to indicate a co-regency. Murnane (1977, p. 112) argues that the statues are not a group as once thought. First, the statues “were found not in position but thrown into a pit, the smaller actually stuffed inside the larger.” Second, “the smaller statue is worked differently from the larger” suggesting “that either the two statues are not a proper pair or that the smaller one was converted to royal status sometime after its completion.”

Although the above data could be interpreted in either way, there are two important pieces of data which may in fact point to the existence of a co-regency between Pepi I and Merenre. The year five count of Merenre records an

occasion when the king received the Nubian chieftains on the southern border. If Merenre had been serving as co-regent with his father, it is unlikely that he would have dated such a monument until after his accession to the throne, although he might well have begun counting the year of his reign from the time when he became co-regent (Smith 1971, p. 193).

This seems to be good evidence that Merenre began his sole rule in “the year after the 5th count” (the fifth count would have most likely been the year that Pepi I died). For him to receive the homage of Nubian chiefs would seem to indicate his coronation year, that is, the year he began to rule solo. However, Baud (2006, p. 150) believes this could be a theoretical date. Baud, however, gives no reason why this could be a theoretical date.