The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

This paper overviews the recent work of Peter Enns, The Evolution of Adam, examining the implications of Enns’s conclusions for the topics of biblical inspiration and inerrancy, human origins, and the exegesis of the biblical text. Included in this overview is a discussion of Enns’s theological and philosophical assumptions that impinge upon his conclusions, as well as the published concerns that prominent biblical scholars have expressed relating to those conclusions. This paper contends that the views expounded in The Evolution of Adam are flawed at a foundational level, and aims to show that Enns’s incarnational model of Scripture is theologically unsound, that his presupposed view of the origin of humanity is scientifically unwarranted, and that his understanding of the purpose and meaning of the Creation account in both Genesis and Paul’s interpretation of Genesis is biblically unsubstantiated.

Keywords: accommodation, Adam, evolution of Adam, history, human genome project, human origins, incarnational model, inerrancy, inspiration, myth, New Testament use of the Old Testament, orthodoxy, Paul (the Apostle), Peter Enns, presuppositions, Proto-Israel, reinterpretation, theistic evolution

Introduction

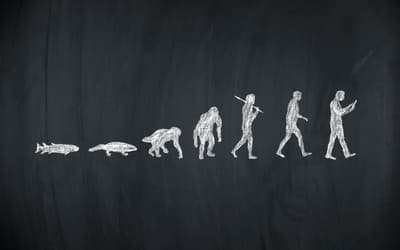

Published in January of 2012, Peter Enns’s work, The Evolution of Adam: What the Bible Does and Doesn’t Say about Human Origins, has generated shockwaves through Christian academia. Enns, in his book, affirms a position known as “theistic evolution,” which asserts that biological (Darwinian) evolution is a scientifically confirmed fact, but also that God was responsible for overseeing and directing the evolutionary development of all the various life forms. Enns’s position is hardly original; theistic evolution has long been promoted as a way for Christians to hold to some semblance of the integrity of Scripture while simultaneously maintaining a degree of respectability within the secular scientific community that has almost uniformly accepted the viability of evolutionary theory. This position has, in fact, been looked upon as a happy medium even by biblical scholars considered to be markedly conservative, theologically speaking (for example, Kidner 1967, pp. 26–31). What is unique about Enns’s book, therefore, is not its attempt to combine evolutionary theory with Scripture, but rather the manner in which it does so, and his reassessment of the Apostle Paul’s view of Adam in the process (see Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15). Whereas many theistic evolutionists look for an actual “Adam” who became head of the human race, Enns argues for an even further departure from biblical literalism while still maintaining his acceptance of an orthodox view of the inspiration of Scripture and the inerrancy of the Genesis creation record. Since differences between competing views of human evolution can be highly nuanced, especially when the subject of theology becomes intertwined, it is best to let Enns speak for himself in defining the key differences. With respect to the views of mainstream theistic evolutionists, he writes:

Some understandably seek to merge evolution with Adam in an attempt to preserve what they perceive as the heart of Paul’s teaching on Adam, yet without dismissing natural science. In other words, evolution is fine so long as an “Adam” can be identified somehow, somewhere. So, for example, it is sometimes argued that Adam and Eve were two hominids or symbolic of a group of hominids with whom, at some point in evolutionary development, God entered into a relationship. At this point God endowed them with his image, thus making them conscious of God and thereby entering into a covenant relationship with them. Such a scenario is thought to preserve at least the general story of Genesis. (Enns 2012, p. 138)1

Enns voices several objections to this position, one of which, strangely enough, concerns the awkward blending of biblical and evolutionary perspectives:

It is ironic that in trying to hold on to biblical teaching a scenario is proposed that the Bible does not recognize: gradual evolution over millions of years rather than the sudden and recent creation of humanity as the Bible has it. Now I will say that it is possible that, tens of thousands of years ago, God took two hominid representatives (or a group of hominids) and with them began the human story where creatures could have a consciousness of God, learn to be moral, and so forth. But that is an alternate and wholly ad hoc account of the first humans, not the biblical one. One cannot pose such a scenario and say, “Here is your Adam and Eve; the Bible and science are thus reconciled.” Whatever those creatures were, they were not what the biblical authors presumed to be true. They may have been the first beings somehow conscious of God, but we overstep our bounds if we claim that these creatures satisfy the requirement of being “Adam and Eve.” (Enns 2012, p. 139)

Stated another way, Enns contends that there is no way for the assumptions of an evolutionary perspective of human origins to be reconciled—even superficially—with the Genesis account. The text of Genesis, therefore, must be read on its own terms, even if it flatly contradicts the mainstream consensus on human origins, as Enns later points out:

Searching for ways to align modern-scientific and ancient-biblical models of creation—no matter how minimal—runs the risk of obscuring the theology of the biblical texts in question. The creation stories are ancient and should be understood on that level. Rather than merge the two creation stories—the scientific and the biblical—we should respect that they each speak a different language. The fact that Paul considered Adam to be the progenitor of the human race does not mean that we need to find some way to maintain his view within an evolutionary scheme. Rather, we should gladly acknowledge his ancient view of cosmic and human origins and see in that very scenario the face of God who seems far less reluctant to accommodate to ancient points of view then we are sometimes comfortable with. (Enns 2012, p. 139)

Described in a nutshell, the chief difference between Enns and other proponents of theistic evolution may well be Enns’s willingness to promote an alternative understanding of Paul’s theological assumptions, beliefs, and assertions in order to reduce tension between the straightforward, literal reading of the Genesis creation record and the alleged scientifically-defensible fact of human evolution. According to Enns, when Paul spoke about Adam, he was not communicating actual history (though Paul believed that he was), rather, he was highlighting an important theological fact (the universal sinfulness of man), employing the most foundational biblical idiom available to him (Enns 2012, p. 142). While this may seem to run contrary to a normal orthodox perspective on the inspiration and inerrancy of Scripture, it is consistent with Enns’s own model. He argues:

A proper view of inspiration will embrace the fact that God speaks by means of the cultural idiom of the authors—whether it be the author of Genesis in describing origins or how Paul would later come to understand Genesis. Both reflect the setting and limitations of the cultural moment. (Enns 2012, p. 143)

According to Enns, it is thus permissible for the book of Genesis and Paul’s later understanding of human origins to be “wrong” in the generic sense of the word and still be divinely inspired and “inerrant” when understood against their respective cultural backgrounds and squared with the theological messages they aim to teach.

Such a conclusion is confusing, no doubt. It casts the book of Genesis, the Apostle Paul’s understanding of the Old Testament’s history, and the origin of humanity into a whole new light. However, is Enns’s view biblically permissible? Does it really match with what the Bible itself asserts about its status as an inspired, inerrant book? Furthermore, does Enns’s model of theistic evolution do justice to the scientific evidence? Is it truly able to produce harmony between the Bible’s record of creation and the mainstream understanding of biological evolution? Most importantly, does Enns correctly interpret the biblical text? Does his view align with how the individual authors (both human and divine) intended for themselves to be understood? In seeking to answer these questions, this review will now turn to an extended evaluation of the content of The Evolution of Adam. It will be followed by a series of critiques and conclude with a verdict on the adequacy and acceptability of Enns’s approach.

Content

Enns’s purpose for writing The Evolution of Adam is twofold: The first, he writes, is to combat “the relentless, articulate, and popular attacks on Christianity by the New Atheists” whose recent writings

have aggressively promoted evolution and argued that evolution has destroyed the possibility of religious faith, especially a faith like Christianity, whose sacred writings contain the story of Adam, the first man created out of the dust several thousand years ago. (Enns 2012, p. ix)

The second is to interact with the “well publicized advances in our understanding of evolution, particularly genetics” (Enns 2012, p. ix). Enns makes his starting assumptions abundantly evident in his point-blank assertion,

The Human Genome Project, completed in 2003, has shown beyond any reasonable scientific doubt that humans and primates share common ancestry. (Enns 2012, p. ix)

He attempts to reconcile the presumed indisputable fact of human evolution with the biblical text by contending that “Scripture [is] a product of the times in which it was written and/or the events took place” (Enns 2012, p. xi) and thus bears the marks of its historical setting(s). In defense of the perspective he advances in his book, he gives three opening premises:

(1) Our knowledge of the cultures that surrounded ancient Israel greatly affects how we understand the Old Testament—not only here and there but also what the Old Testament as a whole is designed to do. (2) Because Scripture is a collection of discrete writings from widely diverse times and places and written for diverse purposes, the significant theological diversity of Scripture we find there should hardly be a surprise. (3) How the New Testament authors interpret the Old Testament reflects the Jewish thought world of the time and thus accounts for their creative engagement of the Old Testament. It also helps Christians today understand how the New Testament authors brought together Israel’s story and the gospel. (Enns 2012, p. xi)

It is important to note that Enns does not argue that Adam evolved, per se, but rather

that our understanding of Adam has evolved over the years and that it must now be adjusted in light of the of the preponderance of (1) scientific evidence supporting evolution and (2) literary evidence from the world of the Bible that helps clarify the kind of literature the Bible is—that is what it means to read it as it was meant to be read. (Enns 2012, p. xiii)2

This contention has a particularly significant bearing on the interpretation of the Pauline writings at two major junctures: Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15. Accordingly, Enns sets out to demonstrate not only that the Genesis account of human origins needs to be reevaluated, but that Paul’s understanding of Adam must be as well (Enns 2012, p. xviii). Enns states his goal for this book in the following way:

[To] show that Paul’s use of the Adam story serves a vital theological purpose in explaining to his ancient readers the significance for all humanity of Christ’s death and resurrection. His use of the Adam story, however, cannot and should not be the determining factor in whether biblically faithful Christians can accept evolution as the scientific account of human origins—and that the gospel does not hang in the balance. (Enns 2012, p. xix)

In order to see how Enns goes about arguing this bold thesis statement, it is necessary to consider his presuppositions concerning Genesis and the Pentateuch. On this subject, he notes that while the undermining of the authority, accuracy, and historicity of Genesis could indeed undermine the authority of the entire biblical text, he maintains that there is sometimes a real need to challenge traditional views (Enns 2012, p. 7). Significantly, Enns rejects the traditional view of the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch in the second millennium BC, looking instead to the Babylonian captivity as a key time in the “formation of Israel’s Scripture as a self-defining statement” (Enns 2012, p. 9). This revised understanding of the writing of Genesis must serve to adjust the reader’s thinking about what to expect from the book in terms of its theology and message (Enns 2012, p. 10). Consistent with his markedly Wellhausian stance on the composition of the Pentateuch, Enns regards Genesis as a text fraught with “ambiguities and inconsistencies” (Enns 2012, p. 12). Without restating his defenses for presupposing this view on the composition of Genesis, it is worth noting his pointed conclusion:

The Pentateuch was not authored out of whole cloth by a second-millennium Moses but is the end product of a complex literary process—written oral, or both—that did not come to a close until the postexilic period. This summary statement, with only the rarest exception, is a virtual scholarly consensus after one and a half centuries of debate. (Enns 2012, p. 23)3

Supposedly, seeing the validity of the postexilic date of the composition of the Pentateuch helps readers to “understand the broad purpose for which it was compiled” (Enns 2012, p. 26). Summarily stated, the formulation of the Pentateuch specifically, but also of the Hebrew Bible generally, as Enns sees it, was “an exercise in national self-definition in response to the Babylonian exile” (Enns 2012, p. 28).

Having established his outlook on the composition of the Pentateuch, Enns goes on to demonstrate how the content of Genesis was allegedly impacted by the stories and myths of the surrounding ancient Near Eastern peoples. He writes:

Placing Genesis side by side with the primordial tales of other ancient cultures helps us gain a clearer understanding of the nature of Genesis and thus what we as contemporary readers have a right to expect from Genesis. Such comparisons have made it quite clear that Israel’s creation stories are not prepared to answer the kinds of questions that occupy modern scientific or even historical studies. (Enns 2012, pp. 35–36)

Comparing the Genesis creation record with the Enuma Elish, he contends that Genesis is not a prototype for the Babylonian myth, but rather presupposes the “far older Babylonian theology of the dominant culture” (Enns 2012, p. 39).4 Because of the presumed connection between the Enuma Elish and the biblical creation record,

any thought of Genesis 1 providing a scientifically or historically accurate account of cosmic origins, and therefore being wholly distinct from the ‘fanciful’ story in Enuma Elish, cannot be seriously entertained. (Enns 2012, pp. 40–41)5

Similarly, Enns draws comparisons between the biblical Flood narrative, the Epic of Gilgamesh, and the ancient myth of Atrahasis. Though he admits that the biblical account has unique polemical elements, he concludes that

The distinct theology of the biblical flood story, however, does not imply that it is of a higher historical or scientific order than the other ancient flood stories. (Enns 2012, p. 49)

To summarize, therefore, Enns asserts that the book of Genesis, as a product of its own time and culture, is not necessarily any less “mythological” or any more historically accurate than contemporary non-inspired sources, but that it still conveys a true theological message.6

To follow along with Enns’s line of argumentation and assuming that it is not warranted to read the early chapters of Genesis as truly representative of actual history, the question remains to be asked: How did ancient Israel perceive the creation narrative? The following remark about the relationship between Israel’s cosmological beliefs and the nation’s identity helps to set the stage for Enns’s response to this question:

Ancient worship was in effect a celebration of the intersection between divine primordial activity and present earthly reality. Israel’s creation stories, as we have seen, inherited many of the themes in stories of their more ancient neighbors. And like them, Israel also celebrated the intersection of primordial time and present time. Israel’s creation stories were not simply accounts of “how it all began.” They were statements about the continuing presence of God who acted back then. Israel’s creation stories rooted their present experiences in the very origins of the cosmos. (Enns 2012, pp. 61–62)

According to Enns, one of the main locales where this intersection is found is in the Adam story of Genesis 1 and 2. In view of the following parallels, Enns (2012, p. 66) opts to read the account of Adam’s creation as a highly figurative story about Israel’s origin:

| Comparison in the Stories of Israel and Adam | ||

|---|---|---|

| Israel | Adam | |

| Creation of Israel at the Exodus | → | Creation of Adam out of dust |

| Commandments (law of Moses) | → | Command (the tree) |

| Land of Canaan | → | Garden paradise |

| Disobedience leads to exile/death | → | Disobedience leads to exile/death |

Thus, in Enns’s view, Adam is “proto-Israel,” and the story is not about humanity’s beginnings, but about Israel’s beginnings.7 As Enns argues, “When seen from this perspective, efforts to reconcile Adam and evolution become unnecessary—at least from the point of view of Genesis” (Enns 2012, p. 70).8

In view of this explanation of Adam’s function within the confines of the book of Genesis, the question remains: How does Enns’s position correlate with Paul’s perspective on Adam and the Genesis creation narrative? Enns observes:

The conversation between Christianity and evolution would be far less stressful for some if it were not the prominent role that it plays in two of Paul’s letters, specifically in Romans 5:12–21 and 1 Corinthians 15:20–58. In these passages, Paul seems to regard Adam as the first human being and ancestor of everyone who ever lived. This is a particularly vital point in Romans, where Paul regards Adam’s disobedience as the cause of universal sin and death from which humanity is redeemed through the obedience of Christ. (Enns 2012, p. 79)

A straightforward reading of Paul would seem to necessitate, in fact, a real, historical Adam. In contrast to a straightforward reading of Paul when it comes to Adam, however, Enns contends that Paul’s writings were conditioned by two factors: (1) the Jewish climate of the day, which was “marked by imaginative ways of handling Scripture” and (2) Paul’s uncompromising Christ-centered focus (Enns 2012, p. 81). Notably, Enns claims,

Paul is not doing “straight exegesis” of the Adam story. Rather, he subordinates that story to the present, higher reality of the risen Son of God, expressing himself within the hermeneutical conventions of the time. (Enns 2012, p. 81)

Accordingly, Enns contends that Adam, understood by Paul as the first human, “supports Paul’s argument about the universal plight and remedy of humanity, but it is not a necessary component of that argument” (Enns 2012, p. 82). He concludes,

To put it positively, as Paul says, we all need the Savior to deliver us from sin and death. That core Christian truth, as I see it, is unaffected by this entire discussion. (Enns 2012, p. 82)9

Ultimately, “Paul’s use of the Old Testament, here or elsewhere, does not determine how that passage functions in its original setting” (Enns 2012, p. 87). More specifically, Paul may employ “Adam” in a way contrary to (or at least not perfectly commensurate with) how he functioned in the Genesis narrative, but this ought not detract from the validity of the theological argument that Paul is making concerning humanity’s universal sin problem and need for a Savior.10 Thus, even though the account of Adam in Genesis was to be understood—in its original setting—as a record of “proto-Israel,” Paul presses the story into service in a different fashion and, by reinterpreting the text as a factual historical record about the first human, aims to demonstrate man’s pervasive sin problem and universal need for a Savior. The Genesis account of Adam’s sin becomes “Exhibit A” among Paul’s supporting evidences.

In discussing Paul as an ancient interpreter of the Old Testament, Enns writes, “Paul (and other biblical writers) shared assumptions about physical reality with his fellow Hellenistic Jews” (Enns 2012, p. 94). In other words, Paul was a product of his own times, and imbibed the views of his contemporaries when it came to the subject of human origins. He thus employs the Genesis record of Adam in his theological argumentation under the assumption that it is an accurate representation of history, when in fact, it is not. Enns continues:

Many Christian readers will conclude, correctly, that a doctrine of inspiration does not require “guarding” the biblical authors from saying things that reflect a faulty ancient cosmology. If we begin with assumptions about what inspiration “must mean,” we are creating a false dilemma and will wind up needing to make torturous arguments to line up Paul and other biblical writers with modes of thinking that would never have occurred to them. But when we allow the Bible to lead us in our thinking on inspiration, we are compelled to leave room for the ancient writers to reflect and even incorporate their ancient, mistaken cosmologies into their scriptural reflections. (Enns 2012, pp. 94–95)11

The point that Enns makes here is the crux of the issue. To summarize, he asserts that a proper understanding of biblical inspiration allows for errant assumptions and statements reflective of incorrect ancient understandings to permeate the text, and that these errant assumptions and statements are intertwined with, but do not detract from, the truth of the Bible’s theological message.

As Enns says,

Paul’s handling of Adam is hermeneutically no different from what others were doing at the time: appropriating an ancient story to address pressing concerns of the moment. That has no bearing whatsoever on the truth of the Gospel. (Enns 2012, p. 102)

So too, “Paul does not feel bound by the original meaning of the Old Testament passage he is citing, especially as he seeks to make vital theological points about the Gospel” (Enns 2012, p. 103).12

Before moving on to examine some critiques of The Evolution of Adam, it is appropriate to let Enns make some concluding remarks:

When we keep in mind some of what we have seen thus far—the ambiguous nature of the Adam story in Genesis, Adam’s functional absence in the Old Testament, the creative energy invested into the Adam story by other ancient interpreters, and Paul’s creative use of the Old Testament in general—we will approach Paul’s use of the Adam story with the expectation of finding there not a plain reading of Genesis but a transformation of Genesis. We will see that, whatever Paul says of Adam, that does not settle what Adam means in Genesis itself, and most certainly not the question of human origins as debated in the modern world. Paul was an ancient man with ancient thoughts, inspired though he was. Respecting the Bible as God’s Word entails embracing the text in context. (Enns 2012, p. 117)

However much Paul’s view of Adam intersects at points with what we see in Genesis, the Old Testament, and early Judaism, Paul’s Adam stands out. Adam’s primordial act of disobedience invariably brought all subsequent humanity to be enslaved to the power of death and sin. The reason behind Paul’s distinct portrayal of Adam reflects his Christ-centered handling of the Old Testament in general. … Israel’s story, including Adam, is now to be read in light of its climax in the death and resurrection of Christ. In other words, Paul’s understanding of Adam is shaped by Jesus, not the other way around. … I want to suggest … that the uncompromising reality of who Jesus is and what he did to conquer the objectively true realities of sin and death do not depend on Paul’s understanding of Adam as a historical person. (Enns 2012, p. 122)

By saying that Paul’s Adam is not the historical first man, we are leaving behind Paul’s understanding of the cause of the universal plight of sin and death. But this is the burden of anyone who wishes to bring evolution and Christianity together—the only question is how that will be done. … So, although my suggestion here leaves behind the truly historical Adam of Paul’s thinking, so do any other attempts—except those of strict biblical literalists, who reject the evolutionary account of human origins. (Enns 2012, p. 123)

With these conclusions duly noted, this review will now move on to critically evaluate Enns’s presuppositions and interpretations.

Critique

Assessment of Enns’s work may be categorized under three broad headings. The first critique concerns Enns’s presumed standard of the inspiration and inerrancy of the biblical text. Mainly, does Enns’s view of the inspiration and inerrancy of the text remain within the bounds of biblical orthodoxy? If so, is it robust enough to properly ground his interpretation of the early chapters of Genesis and his perspective on humanity’s beginning? The second critique relates to Enns’s outlook on human origins. Does his view match with the language and theology of the biblical text? Is his view truly demanded by the scientific evidence as he claims? Furthermore, is his view logically robust? The third critique centers on Enns’s method of handling the biblical text, especially the passages in the New Testament which, at face value, seem to militate against his view of human origins. Can the New Testament authors really be understood in a way that harmonizes with Enns’s perspective on the Genesis account of Adam and Eve?

Presumed standard of inspiration and inerrancy

The main objection to Enns’s conclusions about Genesis, Paul, Adam, and the origin of man stems from concern over his view of the inspiration and inerrancy of Scripture. Notably, Enns’s view of inspiration and inerrancy, as expressed in The Evolution of Adam is derived directly from his conclusions expounded in a former work, Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament (Enns 2005, cf. Enns 2006a, pp. 203–218; 2007, pp. 219–236). This work has already been reviewed by several prominent Christian scholars, and it is beyond the goal of this review to outline and examine all of the points that the book makes. However, a brief overview of the some of the history of the interaction that has taken place over Inspiration and Incarnation will likely be profitable. In this work, Enns seeks to emphasize

That the Bible, at every turn, shows how “connected” it is to its own world is a necessary consequence of God incarnating himself. … It is essential to the very nature of revelation that the Bible is not unique to its environment. The human dimension of Scripture is essential to its being Scripture. (Enns 2005, p. 20)

Of direct relevance to this review, it is to be pointed out that Enns looks at whether the book of Genesis reports historical fact, or just perpetuates a bunch of stories culled from other ancient literature. Significantly, he rejects a distinct bifurcation between “myth” and history, asserting that “God transformed the ancient myths so that Israel’s story would come to focus on its God, the real one” (Enns 2005, p. 54). As such, he views the Bible as a culturally-conditioned product, but one that still communicates theological truth.

Enns asserts that the Old Testament is a highly diverse collection of literature and

that diversity is inherent to the Old Testament text and not imposed onto the Bible from outside attacks on its unity. … [I]t is an important part of Scripture’s own dynamic. (Enns 2005, p. 73)

In defense of his point, Enns adduces several examples from multiple Old Testament books (cf. Enns 2005, pp. 74–107). Enns’s definition of “diversity” is, however, what many others would generally call “contradiction,” in the sense that one text contradicts the historical, polemical, or theological message of another passage. At any rate, Enns concludes that this diversity shows that “there is no superficial unity” to the Bible (Enns 2005, p. 108). Whatever unity is to be found in the text, Enns argues, is a unity “that should ultimately be sought in Christ himself, the living word” (Enns 2005, p. 110).

Compounding the difficulty of reading the theologically-diverse text of the Old Testament, Enns contends that the New Testament authors did not always interpret and apply the text of the Old Testament in a straightforward fashion. The three points which Enns makes about the New Testament use of the Old are as follows: First, “The New Testament authors were not engaging the Old Testament in an effort to remain consistent with the original context and intention of the Old Testament author.” Second, “They were indeed commenting on what the text meant.” Third, “The hermeneutical attitude they embodied should be embraced and followed by the church today.” He then concludes, “To put it succinctly, the New Testament authors were explaining what the Old Testament means in light of Christ’s coming” (Enns 2005, pp. 115–116). In order to validate his points, Enns offers a brief survey of biblical interpretation in the second temple period (Enns 2005, pp. 116–132), and then, arguing that the Apostolic writers operated according to similar interpretive methodology, adduces several examples of New Testament texts that, he believes, provide evidence that the New Testament authors interpreted and applied the Old Testament text in a manner incommensurate with the original meanings of those respective texts (Enns 2005, pp. 132–142; Enns mentions the use of Hosea 11:1 in Matthew 2:15; Isaiah 49:8 in 2 Corinthians 6:2; Abraham’s “seed” in Galatians 3:16, 29; Isaiah 59:20 in Romans 11:26–27; and Psalm 95:9–10 in Hebrews 3:7–11).

Reception of Enns’s work by the conservative Christian academic community has been largely negative. G. K. Beale, in his review of Enns’s book, expresses great concern over Enns’s contention that the writers of Scripture (especially Genesis) presented myth as history. Despite Enns’s highly nuanced view of the meaning of “myth,” Beale, upon careful reading, concludes, “[Enns] uses ‘myth’ still in the essentially normal sense, that is, stories without an ‘essential historical’ foundation” (Beale 2006, p. 297). The natural consequence of Enns’s view of the inclusion of myth within inspired Scripture means that there are no “grounds upon which one can decide what parts of OT history are historically true and which are not” (Beale 2006, p. 296). Beale refrains from niceties in his conclusion on the matter, saying,

It is apparent that Enns’s overall point … is to affirm that ‘interpreted history’ means significant varying degrees of distortion of the record of that history for the purpose of making a theological point. (Beale 2006, p. 298)

So too, Beale contends that Enns merely uses the word “diversity” as a covering for what he really means—error (Beale 2006, p. 300). Later, in examining Enns’s assumptions on the issue of socially constructed cultures, presuppositions, and biblical interpretation, Beale writes,

Of course, Enns himself also has his own preconceptions (which he surely would admit), and these are preconceptions formulated by his own socially constructed reasoning abilities. Why could not his preconceptions be the ones that are distorting Scripture? (Beale 2006, p. 306)

He does not shy away from noting that he thinks Enns “has been too influenced by some of the extremes of postmodern thought” (Beale 2006, p. 303).13

D. A. Carson, much like Beale, in his review of Enns’s work, takes issue with Enns’s assertion that the “historical” texts of the Old Testament (specifically in Genesis) contain “transformed” (that is, reinterpreted) myths. In particular, Carson observes that

while Enns rightly asserts that there is no convincing evidence of direct borrowing between Genesis and the relevant ANE accounts of creation and flood, he does little to point out the differences. That the categories of thought are remarkably similar is obvious, and should cause no surprise among those who fully recognize how much the biblical revelation is grounded in history …; yet competent scholars have laid out the differences between Genesis and the other ANE accounts with penetrating attention both to detail and the big picture, and Enns does not interact with that literature. Had he done so, perhaps his argument would have been a tad less tendentious. (Carson 2006, p. 34)

Many of Carson’s concerns with Enns’s book relate to Enns’s assertions on the New Testament’s use and interpretation of the Old Testament. Contrary to Enns’s arguments, Carson contends that there is a marked distinction between how Paul and the other New Testament writers employed Old Testament passages in their arguments vis-à-vis the use of the Old Testament by their contemporaries. He writes,

If Paul’s way of reading the Hebrew Bible, the OT, is methodologically indifferentiable from the way of reading deployed by his unconverted Jewish colleagues, how are they managing to come to such different conclusions while reading the same texts? (Carson 2006, p. 40)

He remarks that the difference comes down to much more than Paul’s belief in the resurrected Christ (Carson 2006, p. 41). Rather, he asserts that the New Testament authors were well aware of the theological trajectories of the Old Testament. Accordingly, he states:

Their hermeneutic in such exposition, though it overlaps with that of the Jews, is distinguishable from it, and at certain points is much more in line with the actual shape of Scripture: it rests on the unpacking of the Bible’s storyline. (Carson 2006, p. 44)

Carson concludes appropriately,

The failure to get this tension right—by “right,” I mean in line with what Scripture actually says of itself—is what makes Enns sound disturbingly like my Doktorvater on one point. Barnabas Lindars’s first book was New Testament Apologetic? The thesis was very simple, the writing elegant: the NT writers came to believe that Jesus was the Messiah, and that he had been crucified and raised from the dead. They then ransacked their Bible, what we call the OT, to find proof texts to justify their new-found theology, and ended up yanking things out of context, distorting the original context, and so forth. Enns is more respectful, but it is difficult to see how his position differs substantively from that of Lindars, except that he wants to validate these various approaches to the OT partly on the ground that the hermeneutics involved were already in use (we might call this the “Hey, everybody’s doing it” defense), and partly on the ground that he himself accepts, as a “gift of faith,” that Jesus really is the Messiah. This really will not do. The NT writers, for all that they understand that acceptance of who Jesus is comes as a gift of the Spirit (1 Cor 2:14), never stint at giving reasons for the hope that lies within them, including reasons for reading the Bible as they do. The “fulfillment” terminology they deploy is too rich and varied to allow us to imagine that they are merely reading in what is in fact not there. They would be the first to admit that in their own psychological history the recognition of Jesus came before their understanding of the OT; but they would see this as evidence of moral blindness. As a result, they would be the first to insist, with their transformed hermeneutic (not least the reading of the sacred texts in salvation-historical sequence), that the Scriptures themselves can be shown to anticipate a suffering Servant-King, a Priest-King, a new High Priest, and so forth. In other words, Enns develops the first point but disavows the second. The result is that he fails to see how Christian belief is genuinely warranted by Scripture. No amount of appeal to the analogy of the incarnation will make up the loss. (Carson 2006, pp. 44–45)

In addition to Beale and Carson, Bruce K. Waltke has expressed doubts about the helpfulness of Enns’s work, suggesting that his model

represents the Mosaic Law as flexible, the inspired religion of Israel in its early stage as somewhat doctrinally misleading, the Chronicler’s harmonization as incredible, NT teachings as based on questionable historical data, and an apologetic for Jesus of Nazareth’s Messianic claim as arbitrary. (Waltke 2009b, p. 83)

More so than Beale and Carson, Waltke interacts with Enns’s work on an exegetical level, offering alternative explanations to the interpretational difficulties that Enns adduced in chapters 3 and 4 of his book. It is beyond the scope of this paper to look in detail at each of the responses. The point is, as Waltke makes clear, that “Every text on which Enns’s model of inspiration depends is open to other viable interpretations” (Waltke 2009a, p. 117). Waltke seems to have little difficulty in harmonizing the supposedly “diverse” Old Testament texts, which may well indicate that Enns is predisposed to “finding” contradictions, rather than attempting to see what the collective witness of Scripture is attempting to communicate.

Additionally, Waltke disagrees with Enns on the New Testament writers’ use of the Old Testament. Getting to the heart of the issue, he writes,

As an alternative to interpreting the apostles as grounding some of their doctrines in the allegedly fictitious traditions of Second Temple literature, I prefer to think that these stories cited by the apostle are historically true. In my opinion Second Temple literature preserved, not generated, these non-biblical stories. The apostles seem to represent these ancient traditions as real history and so has the church in the history of interpretation. If the stories are not true, the theological truth based on them is also called into question. A community to sustain itself must be based on reality, not on fiction. Though Enns is trying to be helpful, he does not succeed. (Waltke 2009b, p. 93, emphasis added)

Continued interaction between Enns and Waltke (cf. Enns 2009b, pp. 97–114) brought little resolution to their differences, except on a select number of minor issues. In the end, however, the inevitable conclusion that Waltke reached is that Enns’s view of biblical inerrancy and infallibility does not reside within an orthodox definition. He boldly contends:

Tensions in the Bible do not trouble me; they mirror the messiness of life and promote profitable theological reflection and growth. But Enns takes us beyond diversity. His alleged entailments of his interpretation of the model of incarnational inspiration include—at least so it seems to me—such human foibles as contradictions, mistaken teachings in earlier revelation, and building doctrines on pesher, arbitrary interpretations, and he does not correct me. These assertions go beyond mere tensions and call into question the cogency of the biblical writers, the inerrancy of the Bible’s Source, and the infallibility of the divine/human texts. (Waltke 2009a, pp. 127–128)

By far the most thorough review of Enns’s former work has come from the pen of James Scott. Over against Enns’s contention that a proper doctrine of Scripture can be derived from the examination of the characteristics (as opposed to the statements) of Scripture itself, Scott asserts:

It is illogical to suppose that the Bible’s own doctrine of Scripture can be modified by any study of the data. Our understanding of what Scripture says about itself can be corrected only if the meticulous exegesis of its relevant didactic statements yields a superior understanding of them. (Scott 2009a, p. 132)

He charges that Enns ignores what Scripture actually says about itself with respect to the doctrines of inspiration and inerrancy, allowing his interpretation of biblical “behavior” to trump the clear interpretation of biblical statements (Scott 2009a, pp. 134–135). Scott later posits that the only course to follow is to determine precisely what the Bible teaches about itself in relation to inspiration, “and see what implications that doctrine has for our handling of Scripture” (Scott 2009a, p. 137).

As Scott demonstrates, Scripture claims to be the written word of God (2 Corinthians 6:16; Hebrews 3:7; 4:12; cf. Romans 3:2), though it was transcribed by humans (cf. Romans 10:19–20). Scripture often mentions both the divine and human authors together (Acts 3:18; 28:25; Romans 1:2; 2 Timothy 3:16; 2 Peter 1:21). Scott thus concludes that

This human instrumentality implies that God is the originating and controlling author of Scripture. That is, he determined what men would write in the Bible, not only as their message, but more importantly as his message. God used the writing efforts of inspired men to speak his word to us. He did not merely approve or endorse what they wrote, or have enough influence on what they wrote that he could claim it as his own; rather, he caused them, through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, to write what they wrote. God did not concur with what the human writers wanted to write; they concurred with what he wanted to write. (Scott 2009a, p. 141)

Of natural consequence to this reality, therefore, the following remains true: Whether they [the human authors] were writing things learned by special revelation or by ordinary means, “a supernatural divine influence superintended, directed and controlled the writers of Scripture when they were writing.” The human aspect of inspiration, then, is not the writer’s prior nonrevelational learning, but his active, thoughtful concurrence during the inspiring work of the Spirit and willful writing in accordance with the impetus of the Spirit. (Scott 2009a, p. 145)

Additionally, several aspects of God’s own character have an incredibly direct bearing on Scripture, three of which are highlighted by Scott:

First, God is omniscient: he “

knows everything” (1 John 3:20); “his understanding is beyond measure” (Ps 147:5). From this we can infer that God cannot say or cause to be written in his word anything that he thinks is true, but in fact is false. The statements of Scripture cannot and therefore do not manifest any ignorance on God’s part. Inspiration does not render the human writer omniscient (see, e.g., 1 Cor 1:16) or make the biblical text exhaustive of divine knowledge at any point (cf. 1 Cor 13:8–12), but the Author of Scripture nonetheless speaks out of his omniscience.Second, God is truthful. That is, he always communicates the truth. “

God is true” (John 3:33); hence, his words are “trustworthy and true” (Rev 22:6). He “will not lie” (1 Sam 15:29); he “never lies” (Titus 1:2). Because God is omniscient, he will not unintentionally say something that is untrue; because he is truthful, he will not intentionally say something that is untrue. God not only intends to speak the truth, but, because he is omniscient, always succeeds in stating what is true. Because inspiration gives us “the immediate word of God Himself,” Warfield states, it gives to Scripture “a trustworthiness … which is altogether Divine.”Third, God is immutable, or unchangeable. “

I the Lord do not change” (Mal 3:6). He remains “the same” forever (Ps 102:27). Thus, his word is “unchangeable” (Heb 6:17–18). He “cannot deny himself” (2 Tim 2:13), and thus he is always self-consistent and noncontradictory. If he is immutable, his truth, as expressed in Scripture, never changes. If he is self-consistent and noncontradictory, his written word must be free of inconsistencies and contradictions. (Scott 2009a, pp. 148–49)

Scott also contends,

Since God is an objective Being, it follows that his truth is also objective. There is one standard of objective truth, and that is the knowledge held by God. The word of God expresses that knowledge, and thus is objectively true, conforming to what really is. There is no human standard, ancient or modern, that determines what truth is. There is only the eternal and perfect standard of divine knowledge. Whenever God speaks, he necessarily speaks in accordance with that standard. Thus, everything that he says in his written word, the Scriptures, expresses and is perfectly consistent with the objective truth of divine knowledge.

Because the God of all truth is the author of Scripture, we say that Scripture cannot contain any error (i.e., is infallible) and therefore does not contain any error (i.e., is inerrant). It is without error in the sense that it is consistent with what God knows to be true and what is objectively true in God’s Being and in his creation (including what has happened in history). Furthermore, since God is immutable and his word is therefore self-consistent, it follows that no passage of Scripture contradicts or is inconsistent with any other passage of Scripture. (Scott 2009a, p. 149)

To summarize, Enns’s work suggests that the Bible promotes erroneous worldviews, contains discrepancies, and makes faulty interpretations. However, such a claim directly conflicts with what the Bible clearly maintains about itself, as well as with what it reveals of the character of its divine Author, God Himself. Scott rightly quips:

Enough of this double-talk; error and contradiction cannot be redefined as integrity and trustworthiness to suit Enns’s view of an error- and contradiction-laden “word of God.” Without an objective standard of truth … Enns’s whole position reduces to irrationality. Because he does not start with the immutable God of absolute truth, who speaks only in accordance with that truth—doctrine revealed in Scripture, not dreamed up by theologians and imposed on it—Enns’s position is self-destructive in the end. (Scott 2009a, p. 154)

Scott further recognizes that, while Scripture is invariably true, it does interact with other sources and beliefs that are not true. Nevertheless, Scripture often refers to ancient concepts and beliefs without endorsing whatever mythological baggage clings to them (Scott 2009a, pp. 159–160). The idea of “accommodation” must not allow for the endorsement of error. Notably, Christ Himself, in interacting with the religious leadership of His day, sought to correct errant perspectives rather than “accommodating” Himself to His audience and assuming, if even for the sake of argument, that their views were true. Scott rightly notes,

Stating a known falsehood, either in a narrative of what ostensibly happened or as the premise of an argument, is lying, pure and simple. What one’s hearers happen to believe is irrelevant. (Scott 2009a, p. 162)

In relation to Paul particularly, Scott contends,

Most people who speak of what Paul meant are focusing on what Paul understood as he wrote, as if he was not inspired, and in that they err. (Scott 2009a, p. 169)

The meaning of the text is that which is underwritten by God, the meaning which He intends for the text as communicated in the precise words and expressions He employs. Scott adds:

We must always bear in mind that the human writer’s understanding of what he was writing under inspiration was never the complete meaning, in all of its depth and implications, as understood by God. The human writers held many views, some of them quite erroneous, but the significance of inspiration is that out of the mix of ideas in their minds, only true statements were written down. (Scott 2009a, p. 170)

Consequently, when it comes to the New Testament’s use of the Old Testament,

If the NT asserts that a certain meaning is in an OT text, then it must be there, or else the word of God is inconsistent and its Author is making false statements. (Scott 2009a, p. 174)14

This is something which Enns apparently cannot accept.

The point behind this lengthy presentation of responses to Inspiration and Incarnation is to show that Enns’s incarnational model of the inspiration of Scripture is deeply flawed at multiple points. It is both presuppositionally and exegetically unsound. As such, it cannot serve as a viable foundation for the determination of a true biblical perspective on creation and human origins.

Predetermined outlook on human origins

Enns’s perspective on inspiration is not the only questionable factor underlying his conclusions in The Evolution of Adam. In fact, it ought to go without saying that his basic assumptions concerning the validity of human evolution (and, by extent, his belief in evolutionary theory as a whole) are deserving of critique. Darwinian evolution, in spite of all of its pedigree, has not actually been proven. In truth, because evolutionary theory is conjecture about past events made in the light of certain interpretations of modern data pieced together by fallible human interpreters relying on particular (mostly philosophical) axioms, it can never be proven scientifically. This fact alone suggests that evolution’s foundation is shaky; however, when it is combined with the fact that there is no observable evidence confirming the continuation of evolution in the present (and there is certainly no written record documenting the progression of evolution in the past), it becomes all the more questionable whether Enns is warranted in affirming so tenaciously that the theory of evolution is beyond “any reasonable scientific doubt” (Enns 2012, p. ix).

Because this is not a scientific report, this paper will not seek to rebut the theory of evolution in toto; however, it will seek to engage with Enns’s assumption of evolution as a fact in view of (1) the terminology and theology of the Genesis text, (2) the nature of science and its implications for the study of human origins, and (3) the assumptions and logic underlying evolutionary theory.

First, Enns’s assumption that biological evolution is

a fact runs contrary to the terminology and theology

of the Genesis text. Most notably, the repetition of the

phrase “according to its kind

” (ּ למְיִנהֵו ; Genesis 1:12, 21, 25)

indicates that there is a distinguishable order

between the various creatures. While it is sometimes

difficult to determine scientifically where the barriers

are located, the fact remains that the Bible teaches

fixity of the created kinds (not, as some would

erroneously claim, the fixity of species). The text

leaves no room for the supposition that one kind may

give rise to another, regardless of the time involved.

Naturally, Enns might object that this amounts to

reading Genesis’ creation narrative counter to its

function of setting forth a story of “proto-Israel” and

expecting from it answers to questions of origins

that it, as an ancient narrative, was not prepared to

answer. However, if this is truly the case, that is, if

Genesis does not really intend to seriously address

the question of cosmic origins and if it is really about

the beginning of Israel rather than the beginning

of mankind, why is there such a heavy focus on

distinctions in the created order in the first place?

The repetition of the phrase “according to its kind”

becomes completely irrelevant!

Additionally, looking at the issue from a more theological perspective, it can be observed in multiple locations in the text that mankind is a special creation of God, completely distinct from the animals. This is pointedly evident in Genesis 1:26–27, which describes man as being made in God’s image. Enns states:

Although what “image of God” means in its fullest biblical witness may be open for discussion, in Genesis it does not refer to a soul or a psychological or spiritual quality that separates humans from animals. It refers to humanity’s role of ruling God’s creation as God’s representatives. (Enns 2012, p. xv)

There is clearly a measure of validity to Enns’s point in view of the connections drawn in Genesis 1:26 and 28 and, though this author believes that a more nuanced understanding of the imago dei is warranted based upon certain contextual factors in Genesis 1; for the time being, Enns’s view of the image of God will be assumed as accurate. Even granting that the imago dei concerns only humanity’s role as vice regent over God’s creation, this still necessitates seeing a critical distinction between mankind and animals: those who rule versus those who are ruled. This is confirmed by Genesis 9:6 which speaks of murder as a capital offence because it inherently involves the defacing of the divine image in man. Given that Genesis 9:6 speaks to a post-Fall world and is given immediately following God’s pronouncement that animals may be killed for the purpose of food (Genesis 9:2–4), there is explicit textual warrant for seeing humans as being uniquely valued by God. The text pounds a sharp wedge between man and animals, thus demanding that man is seen as much more than an intelligent quadruped evolved from a common ancestor along with other primates. Surely this is also one of the unavoidable theological truths taught in Genesis 2:4–25, which pointedly presents man as specially and uniquely crafted by the creative powers of God (see especially verses 7 and 22).15

Second, Enns’s belief that evolution is an indisputable fact extends beyond the bounds of what can be proven scientifically. The chief argument that Enns adduces for the validity of human evolution are the conclusions of the Human Genome Project, completed in 2003 (Enns 2012, p. ix). However, the conclusions of the Human Genome Project are hardly beyond contestation. Like the theory of evolution itself, the conclusions adduced by the Human Genome Project are limited by at least two factors: First, they are limited by the innate boundaries of scientific research. Science is capable of confirming or denying through the process of experimentation certain facts of the present-day world. However, because scientific experimentation can only access data that exists in the present, any bearing that experiments such as those of the Human Genome Project can have on the discovery of facts lost to history is limited. Science can never actually prove anything about the past; it can only test present data from which inquirers may develop ideas about the past. Second, the conclusions of the Human Genome Project are limited by the presuppositions feeding into the study. In any kind of scientific research, one’s starting assumptions have a direct (sometimes drastic) impact on one’s conclusions. As for evolution itself, since it cannot actually be confirmed scientifically, it is reduced to being nothing more than “a matter of sheer faith,” a “dogmatic belief” that is “no more ‘scientific’ than any other kind of religious faith” (MacArthur 2003, p. 55).

Because those interpreting the results of the Human Genome Project (such as Francis Collins) presumed that biological evolution was a fact, it is hardly surprising that the conclusions reached reflected that underlying belief. Had a similar project been conducted with its researchers assuming an orthodox view of Scripture, it is conceivable that the conclusions would have differed considerably. Indeed, not everyone has drawn the same conclusions when faced with the study of human genetics. For instance, Fazale Rana and Hugh Ross (who, as adamant proponents of progressive creationism, hardly fall under Enns’s despised heading of “strict biblical literalists”) addressed the findings of the Human Genome Project, stating that it largely agrees with various genetic diversity studies and demonstrates that “humanity had a recent origin from a single location” (Rana and Ross 2005, p. 62). The point is not that Rana and Ross are necessarily correct in their interpretation of the data, or that their model for the interpretation of the early chapters of Genesis is viable. However, the fact that they draw different conclusions about the origin of humanity in the face of the same genetic data demonstrates that even those not committed to a wholly literal view of Genesis do not always concur with Enns’s belief that evolution is an irrefutable fact.

Even if there was not some degree of skepticism regarding the conclusions of the Human Genome Project, the fact remains that the theory of evolution leaves many other questions unanswered when it comes to other important lines of evidence. For instance, the concept of human evolution is notoriously lacking when it comes to fossil evidence. Marvin L. Lubenow goes so far as to say that

human evolution has been falsified in that virtually every chart of human evolution since 1990 has question marks or dotted lines at the most crucial point—the transition from australopithecines to true humans. (Lubenow 2004, p. 326)

The conclusion of Lubenow’s book on the exposé of the shoddy evidence for any transitional forms is crucial:

For 150 years, evolutionists have paraded the fossils they have found as evidence for evolution. They promised more and better fossils in the future, hoping that luck and the tooth fairy would validate their hopes. In the early 1970s, when it became obvious that we had a more than adequate sampling of the fossil record, the grim reality dawned that those transitional fossils were not to be found. The punctuated equilibria model of evolution was then invented to explain why they were not found. However, it is imperative to emphasize that the punctuated equilibria model does not remove the need for transitional fossils. It just explains why those fossils have not been found. Certainly, the punctuated equilibria theory is unique. It must be the only theory ever put forth in the history of science that claims to be scientific but then explains why evidence for it cannot be found.

The popular myth is that the hominid fossil evidence virtually proves human evolution. The reality is that this evidence has been a disappointment to evolutionists and is being de-emphasized. In actuality, the human fossil evidence falsifies the concept of human evolution. The Bible, the Word of the living God, clearly declares that humans were specially created. The human fossil evidence is completely in accord with what the Scriptures teach. (Lubenow 2004, p. 334)

The point is that the alleged conclusions of the Human Genome Project which Enns sets forth as comprehensive proof of human evolution, even if they did not contradict the biblical text (and they certainly do), still cannot overcome the problems that evolution faces in other branches of science, such as paleoanthropology. The evidence is simply lacking.16

Third, Enns’s attempt to reconcile Christianity and evolution is inconsistent with the logic behind the development of evolutionary theory. The theory of evolution exists as one of fallen man’s attempts to explain the origin of life (and of the universe) apart from a Creator or, more specifically, the God of the Bible. To reintroduce God back into a world fashioned by evolution is counterintuitive. The unholy union between biblical Christianity and evolutionary theory prompted one anonymous writer to make the following comment almost a century ago. Though lengthy and somewhat dated, it is worthy of careful note:

When we consider that evolutionary theory was conceived in agnosticism, and born and nurtured in infidelity; that it is the backbone of the destructive higher criticism which has so viciously assailed both the integrity and authority of the Scriptures; that it utterly fails in explaining—what Genesis makes so clear—those tremendous facts in human history and human nature, the presence of evil and its attendant suffering; that it offers nothing but a negative reply to that supreme question of the ages, “If a man dies, shall he live again?” that it, in fact, substitutes for a personal God “an infinite and eternal Energy” which is without moral qualities or positive attributes, is not wise, or good, or merciful or just; cannot love or hate, reward or punish; that it denies the personality of God and man, and then presents them, together with nature, as under a process of evolution which has neither beginning nor end; and regards man as being simply a passing form of this universal Energy, and thus without free will, moral responsibility, or immortality, it becomes evident to every intelligent layman that such a system can have no possible points of contact with Christianity. He may well be pardoned if he views with astonishment ministers of the Gospel still clinging to it, and harbors a doubt of either their sincerity or their sanity.

If it be said that most ministers who accept evolution do so only in its milder form, the supernaturalistic which permits of belief in a personal God, but claims that evolution is His method of working, man and nature being products of it, it may be said in reply that this view, quite as much as the naturalistic, necessitates the giving up of the account in Genesis, and generally carries with it the belief that the Bible is but a history of the evolution of the religious idea, and not what it everywhere claims to be, a Divine and supernatural revelation. (Anonymous 2008, pp. 92–93)

Not only have conservative Christians rejected the compatibility of evolution with biblical truth; proponents of evolutionary theory in the secular arena have also viewed the combination of evolution with Christian theism as logically inconsistent. Richard Dawkins expounds on the irreconcilability between a sovereign, all-wise Creator God and the haphazard process of natural selection which is the “driving force” of evolutionary development:

Natural selection, the blind, unconscious, automatic process which Darwin discovered, and which we now know is the explanation for the existence and apparently purposeful form of all life, has no purpose in mind. It has no mind, and no mind’s eye. It does not plan for the future. It has no vision, no foresight, no sight at all. If it can be said to play the role of watchmaker in nature, it is the blind watchmaker. (Dawkins 1996, p. 5)17

Christianity and evolution, in any of its forms, is simply incompatible. Evolution of natural consequence clashes with some of the most foundational truths of Scripture, degrading human dignity by making him a higher form of animal, opposing sound reasoning by replacing an all-powerful Creator with the non-entity called “chance,” and demeaning the truth of Scripture by turning it into a colorful metaphor, a story that conveys some semblance of theological insight, but does not actually convey fact about human origins as it claims to do (MacArthur 2003, pp. 72–84). There is no way that biblical Christianity and evolution can be responsibly, logically harmonized. They tell two different stories, one which assumes God and His creative work from the outset (Genesis 1:1), and the other which was forged in the crucible of the minds of those bent on destroying God. Christianity, at least as the Bible describes it, and the theory of evolution represent an either/or choice; they are not reconcilable.

To conclude, therefore, Enns’s interpretation of the text is shaped by his preconceived conclusion that biological evolution is true—a position for which he can adduce no proof, only the purported, presuppositionally-shaded “evidences” developed by those working from the position of decidedly antibiblical axioms. His conclusion flies in the face of the terminology and theology of the text itself, and his attempt to forge a bond between Christianity and evolution utterly defeats the purpose for which biological evolution was formulated in the first place.

Presupposed understanding of the biblical text

Compounding the problem of Enns’s errant view of inspiration and his unwarranted assumptions concerning human evolution is his poor handling of the biblical text. This is evidenced nowhere better than in his statements about the composition and function of Genesis and the Pentateuch. The assumption that he (and others holding to similar views) in the modern age can more accurately reconstruct “how things really happened” then those living at the time of the writing of the biblical text smacks of arrogance. By contrast, the witness of Scripture for the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch is incredibly strong. The Pentateuch itself forcefully implies that Moses was indeed its author (Exodus 17:14; 24:4, 7; 34:27; Numbers 33:1–2; Deuteronomy 31:9, 11). Similarly, the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch is assumed by later Old Testament writings (Joshua 1:7–8; 8:31–32; 1 Kings 2:3; 2 Kings 14:6; 21:8; Ezra 6:18; Nehemiah 13:1; Daniel 9:11–13; Malachi 4:4). Additionally, the New Testament affirms that Moses indeed authored the Torah (Matthew 19:8; Mark 12:26; John 5:46–47; 7:19; Acts 3:22; Romans 10:5; Hebrews 10:28).18 Gleason Archer and others have compiled impressive lists of biblical and extra-biblical evidences indicating the considerable antiquity of the Pentateuch and implicating Moses as the author.19 The point is that the Enns’s adamant denial of Mosaic authorship and the antiquity of the Pentateuch (Enns 2012, p. 23) in the face of such considerable evidence makes it impossible to believe that his low view of the composition of Genesis does not play into his low view of the interpretation of its content.

Enns’s treatment of the New Testament text is just as poor. While he is right in asserting that the issue of an historical Adam has perhaps the greatest bearing on Paul’s arguments in Romans 5:12–21 and 1 Corinthians 15:20–58, the fact remains that many other passages also militate against the idea of an evolutionary origin for mankind. The fact that the Old Testament authors assumed the cosmology presented in Genesis is quite evident (for example, Nehemiah 9:6; Psalm 102:25; Isaiah 44:24), and this point need not be belabored. However, when it comes to the New Testament, it must be recognized that there are more than a couple of isolated references by Paul to be dealt with. The following New Testament passages are but an incomplete sample of those which clearly assume, imply, or teach a literal view of the Genesis creation account (that is, as a historical record of how the world and humanity came into existence by direct act of God’s creative work in six ordinary days): Matthew 19:4–6; Mark 10:6–9; 13:19–20; Luke 10:50–51; Acts 3:21; 4:24; 14:15–17; 17:24–31; Romans 1:18–25; 8:19–23; 2 Corinthians 4:6; Colossians 1:15–20; 1 Timothy 2:13–14; Hebrews 1:10; 4:1–10; 9:25–26; 11:3–4; James 3:9; 2 Peter 3:3–8; Jude 14; Revelation 4:11; 14:6–7; 21:1–5; 22:2–3.20

In the interest of space and efficiency, only two passages, Matthew 19:4–6 and Jude 14, will be examined here. First, in Matthew 19:4–6, Christ bases His explanation of marriage on the text of Genesis 1. Looking to verse 4, it can be discerned (1) that Christ viewed this passage as authoritative (“Have you not read …”) and (2) that He viewed mankind as having been created in “the beginning.” Based on the New Testament usage of the phrase

from (or in) the beginning” (ἀπʼ ἀρχῆς) it is evident that Christ had in view not merely the beginning of the human race or the institution of marriage, but of “the beginning of the whole creation, which encompasses the whole creation period described in Genesis 1. (Mortenson 2008, p. 320)

This being the case, Christ is clearly implying that the account of man’s creation as Genesis describes it is to be taken seriously. He leaves no room for any sort of evolutionary belief about humanity’s origin. If Christ in this passage, as God-incarnate, is merely accommodating himself to the prevailing view of the day that Genesis 1 was true history, there is at minimum a question about His truthfulness.

Second, Jude 14 makes reference to “Enoch, the

seventh from Adam.

” Clearly, Jude is assuming

the accuracy of the genealogies in Genesis 5 and

1 Chronicles 1. (Luke, in the construction of the

genealogy in the third chapter of his gospel makes

a similar assumption.) The point here is that Jude,

by connecting Adam and Enoch together in the same

genealogical line, evidently assumes that both are

real historical figures. Jude’s assumption leaves no

room for taking Adam as a metaphorical figure or as

anything less than the living, breathing flesh-and-blood

human being that Genesis makes him out to

be. If Enns’s conclusions about the Bible’s allowance

for human evolution are to be believed, at what point

does the “metaphorical Adam” or Enns’s “proto-Israel Adam” give rise to a genealogical line of real

historical figures? In other words, where does the line

of the metaphorical ancestors of Israel leave off and

where does the line of literal ancestors begin? Is Seth

a real person? What about Noah? What about Terah?

Determination of where the genealogies in Genesis,

1 Chronicles, and Luke begin speaking of actual

historical figures is completely arbitrary unless Adam

himself is a real human figure, the direct creation of

God and head of the human race.

Clearly, explaining Paul’s two main references to Adam is not enough; there remains a host of biblical evidence that the Genesis record of creation is to be regarded as fact. That being said, it is necessary to take one last look at Enns’s view of Paul. His contention that Paul (especially in Romans 5) references Adam in a way incommensurate with the original meaning of the Genesis account of Adam, and that he “pressed Adam into new service in view of the reality of the empty tomb” (Enns 2012, p. 132), is still intriguing from a theological standpoint. It is worth noting, however, that Mark Seifrid, in his commentary on Romans with special attention to the use of the Old Testament, makes no reference to Paul’s theology of the resurrected Christ being imposed on his view of Adam (Seifrid 2007, pp. 628–631). A careful reading of Romans 5 indicates, in fact, that there is nothing within the confines of the text itself to support the idea that Paul reinterprets Adam to suit his own message. Such a notion only arises when it is assumed a priori that the early chapters of Genesis do not speak of the origin of the human race. It seems, therefore, that Enns’s contention amounts to nothing more than a clever eisegetical ruse.21

Obviously, Enns’s understanding of the biblical

text in both the Old and New Testaments is skewed.

More fundamentally, though, he does not seem

to recognize the proper foundation necessary for

correctly interpreting the text and drawing from it

theological truth in the first place. The Bible plainly

indicates that the basis for all knowledge and wisdom

is the “fear of the Lord

” ( יִרְאַת יְהוָה ; Psalm 111:10;

Proverbs 1:7; 9:10; 15:33; cf. Job 28:28). The fear of

the Lord entails the utmost reverential awe for God

in recognition of and response to His incomparable

majesty, immeasurable power, and moral

perfection (specifically His attributes of justice and

righteousness; for example, Job 37:22–24), as well as

His merciful forgiveness (Psalm 130:3–4), His great

salvation achieved through the blood of the sacrifice

of Jesus Christ (1 Peter 1:17–21), and all His other

matchless works (Revelation 15:3–4). At a most basic

level, the fear of the Lord is what is demanded of

man in view of God’s absolute holiness (Isaiah 8:13).

It involves reliance upon God (Psalm 33:18; 147:11)

coupled with wholehearted trust in His direction and

deliberate avoidance of evil (Proverbs 3:5–7; 8:13) It

produces, or is at least evidenced in, obedience to and

delight in God’s commandments (Deuteronomy 6:2; 8:6; 10:12–13;

Psalm 112:1; Ecclesiastes 12:13). It

invariably eventuates in the worship of God (Psalm 22:23;

Hebrews 12:28–29; Revelation 19:5).

In view of such passages as Psalm 111:10 and Proverbs 1:7, D. Bruce Lockerbie wisely surmises that the fear of the Lord should rightly be the starting point for all Christian thought. He writes, “Wisdom and knowledge, not reason and intuition, are the goal of all cognition, all learning, all thinking. And the beginning point is an obligatory reverential awe before God the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth” (Lockerbie 1986, p. 9; cf. Mayhue 2003, pp. 50– 53; MacArthur 2009, pp. 86–87). More specifically, as Daniel Castelo argues, the fear of the Lord must provide the necessary grounding for all biblical interpretation and theological method.22 In The Evolution of Adam, Enns himself makes an interesting point that relates well to this point. Commenting on theological connections between the early chapters of Genesis and the book of Proverbs, he writes,

The command not to eat of [the tree of the knowledge of good and evil] is not a random test of faith to see if Adam is worthy—to see if this untainted creature might fall from his perch, so to speak. It is about how such knowledge is to be pursued. Knowing the difference between good and evil, right and wrong, is desirable; it is the wish of every parent for their children, the very goal of what it means to be a mature, faithful, covenant-keeping Israelite. This quest to know right from wrong is articulated in Israel’s wisdom literature, namely Proverbs. Having such wisdom is not “bad” in either Genesis or Proverbs; it is the very picture of what God wants for his people. The issue at stake in the garden narrative is how humans are to obtain such knowledge: in God’s way or in some other way. (Enns 2012, pp. 88–89)

However, as has already been asserted, wisdom begins with the fear of the Lord and, as is evident in the Genesis narrative and elsewhere, is acquired by listening to God’s revealed word (cf. Deuteronomy 4:10; 17:19; 31:12–13). Apparently Enns overlooks this important principle. By reinterpreting God’s word (Genesis and the Pauline epistles alike), he destroys any opportunity to gain from it the intended meaning and truth that are capable of producing real wisdom. This notwithstanding, the comparison that Enns draws between Genesis 3 and Proverbs is insightful (see especially Enns 2012 pp. 89–90). However, the correlation is stripped of the bulk of its meaning and significance if the Genesis account is ahistorical. Succinctly stated, comprehension of the origin of man and of all other related issues (man’s uniqueness, dominion, etc.) begins not with man’s own fallible suppositions (that is, the legitimacy of evolutionary theory) imposed on the text, but with the fear of the Lord and humble submission to the truth which He reveals.

Conclusion

The preceding critique has demonstrated that Enns’s incarnational model of scripture is theologically unsound, that his presupposed view of the origin of humanity is scientifically unwarranted, and that his understanding of the purpose and meaning of the creation account both in Genesis and Paul’s interpretation of Genesis is biblically unsubstantiated.

What is perhaps most disconcerting about Enns’s perspective, however, is that despite holding to it, he nevertheless presumes to remain within the bounds of Christian orthodoxy. Significantly, concerning his perspective on Paul’s use of Adam, Enns confesses:

What is lost is Paul’s culturally assumed explanation for what a primordial man had to do with causing the reign of death and sin in the world. Paul’s understanding of Adam as the cause reflects his time and place. Although Paul interprets this story in his own distinct way and for his own distinct purposes, the Israelite tradition handed to him still provides the theological vocabulary by which he can express his unique theology. There is no hint of modern arrogance (or heresy) whatsoever in a modern reader’s making that observation. (Enns 2012, p. 124)

On the contrary, this is heresy, for it necessarily ascribes to Paul full responsibility for perpetuating a lie without any textual indicators even hinting at the questionability of the truth value of the “story” in which he grounds his theological assertions. It unavoidably and unashamedly undermines the biblically-based, non-negotiable doctrines of inerrancy and the inspiration of the text by a Being incapable of inventing or endorsing a lie. Enns remarks, “Even without the first man, death and sin are still the universal realities that mark the human condition” (Enns 2012, p. 124). Granted; but if humanity does not have a corporate head ultimately responsible for humanity’s sin nature, then of logical consequence, there can be no deliverance from sin through Christ, who is likewise the corporate head of all the redeemed. Enns gives lip service to “original sin,” being content to have no explanation for why humans are “born in sin” (cf. Enns 2012, p. 125). Scripture is clear that all human beings are sinful from conception (Romans 5:19; cf. Job 14:1–4; Psalm 51:5); however, it is insufficient to be content with the ambiguity of the cause, for the nature of the cause provides the basis for why the form of the solution in Christ’s substitutionary, atoning death was sufficient. Thus, when it comes to Adam, there is not merely a question of historicity (cf. Enns 2012, p. 126), but also of the spiritual and effectual potency of Christ’s work. According to Enns, “Paul pressed Adam into new service in view of the reality of the empty tomb” (Enns 2012, p. 132). Assuming, however, the validity of human evolution and the non-literal explanation of the Genesis text, this means that Paul, in essence, used a lie to “support” the Gospel truth, and a myth to explain the significance of the present (and historical) reality of human sin. To so flagrantly dilute this clear biblical teaching as Enns does can only be described as heresy.

What is to be said in response to Enns’s contention that his views remain within the bounds of Christian orthodoxy when in fact they promote heresy? What is to be said about Enns’s work in the ministry of Christian education when in fact he supports an inherently anti-Christian agenda? The following point, though written almost a century ago, still rings true: