The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

The series of papers by Griffith and White entitled “Chronological Framework of Ancient History” (2022a, 2022b, 2023a, 2023b, 2023c) revisit the ground covered by Ussher (2003), Jones (1993), and many others concerning the history in Genesis 1–11 strictly adhering to the Masoretic text (MT). Using ancient texts from multiple ancient societies, the authors employ an analysis tool they call “durations and triangulations.” Some of the conclusions they reach on the basis of these texts and the authors’ methodology, while not openly contradictory to Scripture, are somewhat questionable based on other data. Also, one possible danger with using this methodology is false identification of duration endpoints, such as equating Babel to Babylon. Relying on this methodology, Griffith and White appear to have conflated some ancient Chinese emperors described in the Shūjīng with the post-Flood history of Noah in Genesis. The Shūjīng, the Shiji, the Zhúshū Jìnián, and other ancient Far Eastern sources are examined to dispute this conflation. In particular, the Miao oral tradition (Truax 1991; cf. Cooper 1995; Hattaway 2018; Savina 1924a) shows that Noah lived about 12 generations before the Chinese rulers described in the Shūjīng.

Keywords: Babel, Babylon, Bamboo Annals, Book of Documents, Book of History, Chinese, chronology, Deluge, Dispersion, Flood, Hmong, Gun-Yǔ Flood, Masoretic Text, Miao, Noah, Nǚwā, Records of the Grand Historian, Sargon of Akkad, Septuagint, Shang Di, Shiji, Shūjīng, Shun, Yáo, Yellow Emperor, Yǔ, Zhúshū Jìnián

Introduction

Many nearly identical timelines for the primordial history related in chapters 1–11 of the Book of Genesis have been developed based strictly on the Masoretic Text (MT) for the Old Testament.1 Two notable examples are those by James Ussher (2003) and Floyd Nolen Jones (1993). Now we can add to these one developed by Kenneth Griffith and Darrell White (2022a, 2022b, 2023a, 2023b, 2023c). These latest efforts by Griffith and White, published as the first five of a much larger set of papers yet to come on “The Chronological Framework of Ancient History” are the focus here.

The Griffith and White (2022a, 2022b, 2023a, 2023b, 2023c) papers pose issues in two main areas discussed here. The first main area regards the effectiveness of the methodology of durations and triangulations (introduced in Griffith and White 2022a). While this tool seems to provide a means of building a multi-layered fabric defining the times and places of biblical events, the method is subject to certain limitations. One must be careful not to generalize beyond the actual coincidences of dates and places into speculations regarding details that might be nothing more than artifacts of the method. Griffith and White seem to take liberties of assigning significance to near misses to make conclusions such as two divisions of the earth and two dispersions of the peoples. One must also consider that one can be fooled by seeming coincidences that are not actually in the data. In this regard, the method depends entirely on the judgment of the analyst to take multiple historical descriptions of events and places and sort out which among them actually refer to the same time and place. For instance, unless Babel and Babylon are the same in both time and space, there is no coincidence of certain end points among some of the durations cited by Griffith and White. Rather, the endpoints do coincide but reference a different place and event than intended.

The second major area of discussion is Griffith and White’s interpretation of the data from the Shūjīng (Book of Documents, or Book of History) vis-à-vis the Deluge, which seems to conflict with a plain reading of the Bible as well as of the ancient Chinese text and of other Far Eastern extra biblical witnesses. In particular, Griffith and White claim that because some dates match within their durations and triangulations methodology that the ancient Chinese emperor named Yáo must be the same person as the biblical Noah.

To address these issues, first we will look at Griffith and White’s durations to see if the conclusions they make regarding division of the land, rebellion of the people, and dispersion of the tribes are reasonable. We believe some are questionable. Then we will turn to examining durations that are part of the triangulation of the date for the founding of Babel. Our assertion here is that insufficient data are exposed to establish the major linchpin of Griffith and White’s argument, that the Babylon whose ruins we know of in modern day Iraq (where Nebuchadnezzar II reigned and Alexander the Great died) was not the Babylon mentioned in a number of their durations. In a separate paper (Griffith and White 2021) published coincidently with Griffith and White (2022b), they claim another Babylon existed: an old Babylon, like old York in England and New York in America. This old Babylon, they say, was identical to Babel. We are not sure that the data exposed support this latter claim even if the existence of old Babylon is factual.

Next, certain ancient Far Eastern texts will be studied to see if they support the conclusion Griffith and White derived concerning the coincidence of the reign of Yáo with the immediate aftermath of the Deluge, contributing to the authors’ deduction that Yáo was a pseudonym for Noah. The Shūjīng and other ancient Chinese texts are studied to pull out the fine details of ancient Chinese history to show that in Yáo (whether he existed or not), they describe an entirely different person from Noah in very different circumstances. Additionally, other ancient Chinese lore is examined to illustrate the lack of connection between Chinese myths of Creation and Deluge versus the records of Yáo and his successors, Shun and Yǔ. Finally, the oral tradition of the Miao people is examined to show that a very strong case can be made that Yáo came approximately 12 generations after Noah.

The few footnotes to this paper are not essential to the flow and can be ignored. They provide additional explanatory details for those who have an interest in certain topics.

Division, Rebellion, and Dispersion

Division

The Bible does not preclude the idea that Noah’s descendants actually met and devised a plan to partition the earth among themselves, even though the Bible clearly says that they did not want to disperse (Genesis 11:1–4). Griffith and White hypothesize a fairly complex planning process and a unique division plan based on their interpretation of their durations. The language “for in his days the earth was divided” (Genesis 10:25, NKJV) could mean a variety of things. The salient expression in Hebrew is נִפְלְגָ֣ה הָאָרֶץ (“land divided”), which allows interpretation. Griffith and White take “division” in Genesis 10:25 (and 1 Chronicles 1:19) to mean a decision process that resulted in a pre-Dispersion “allotment,” and in some places to include allotment of specific parcels to specific peoples. Alternatives not chosen by Griffith and White include taking “division” to mean the actual results of settling the earth, or the beginning of the settlement process, or the reconfiguration of the planet through the movement of tectonic plates. (Snelling and Hodge [2010] argue against geodynamics; cf. Baumgardner [1994]).

Griffith and White posit two separate planning sessions, one in 2254 B.C. (AP-27) and a second in 2247 B.C. (AP-28), approximately seven years apart. The “first division” date is based on a duration of 150 years from the usurpation of Pradyato back to the “division of the earth,” from which the authors derive the 2254 figure (AP-27). We note that on the MT timeline, 2254 is before Peleg’s birth, and it was in his days that the earth was divided. The authors derive the “second/final division” date of 2247 (AP-28) from the birth of Peleg but also from other durations, yielding the seven year gap. Someone might be tempted to chalk up this gap to historical loss of accuracy rather than to posit two divisions, one of which is seven years too early to be strictly biblical. This clearly is more than Scripture portrays and different from other witnesses.

Book of Jubilees chapter 8 (few consider this to be inspired Scripture) relates both how the division plan came about and what the results were. Book of Jubilees tells the story thus: Noah’s sons, unbeknownst to him, began discussions among themselves about where their clans were going to live in the future. At a certain point, they admitted to Noah what they had been discussing. In response, Noah took the leadership role and divided the earth by lot into three portions. One could argue that the initial discussion between Noah’s sons started in 2254 and that their tête-à-tête with Noah happened in 2247, but that seems not to match Griffith and White’s description of two events both involving Noah.

Most of the rest of Book of Jubilees chapter 8 gives landmarks and directions that display geographical knowledge limited to what would be known to well-travelled people native to western Asia in the intertestamental period. In Book of Jubilees, there is no knowledge of the New World or even of its existence, much less where Peru would be, no details about China or the rest of Asia, or of Europe, or of Africa beyond the extreme northeast corner. For a division of the earth in post-Flood times, this seems totally reasonable: they would not know what is “out there” beyond their limited horizon. The possibility that God imparted such knowledge is not evident in Scripture. The O’Hart (1878) “cascading” plan is basically a stepwise refinement of the Book of Jubilees plan, the result of a process that starts with an initial plan put forth by Noah or his sons, and then each succeeding generation allotted the areas they possessed among their sons. Griffith and White posit that the division plan not only indicated a specific parcel for the Peruvians but that Noah himself escorted them to their place (see below).

Rebellion

The rebellion in Genesis 11 is the refusal of the people to obey God by populating the earth and subduing it. How does one put a time frame on this rebellion without fully knowing the mind of God and of the people involved? The climax of the rebellion, not the beginning nor the end, comes with the Tower incident (Genesis 11). Manetho (pseudonym) (ca. A.D. 400), as cited by Jones (1993), claimed in the Book of Sothis that the Tower event culminated in the fifth year of Peleg’s life, which per Jones is the date used by Ussher (2003). Rudd (2019) argues for a date for the Tower of Babel of 2850 B.C. from archeological data to align the Tower with Eridu Temple I. In his scheme, Peleg would have been born after the confusion of languages but before the actual partitioning of the earth.

Jones (1993) entertains the idea that the Tower incident may have occurred much later in the life of Peleg than his birth. Rabbinic tradition from Midrash Rabbah: Genesis (Freedman and Simon 1983) claims a date for the Dispersion and division of the land at the end of Peleg’s life (aged 239 by the MT), which is 234 years later than the Book of Sothis date. Jones favors this scenario. However, the date of Peleg’s death on the MT timeline is 48 years after Abram’s birth, or only 12 years before it taking into account the 60 year “correction” proposed by Smith (2018) and others, which would place the beginning of the Dispersion near Abraham’s birth, which is difficult to reconcile.

The first “rebellion” we read about in the Griffin and White scenario is the rebellion of Noah’s descendants against him and his sons in 2247 B.C., the year of Peleg’s birth. In a separate paper Griffith and White (2021, 77), state that the reason for the rebellion was that the people objected to the division plan put forth in the year of Peleg’s birth. This conclusion is supported at least partially by equating Noah to the ancient Chinese emperor Yáo and finding a rebellion in the same year against Yáo. This will be discussed at length in a later section. The actual start of building the Tower is obscure, although Griffith and White summon large amounts of data to establish the length of the building project (2022b, Duration 19). Griffith and White use Durations 1–5 to establish c. 2234/3 B.C. as the date for the founding of Babel, matching that date to the coincidence of the new moon and vernal equinox of 2233 B.C. We will discuss the founding of Babel below in a separate section.

Dispersion

Griffith and White posit that 55 years separated the finalizing of the division plan from its first activation based on the timeline of Berosus (Griffith and White 2023c). They also assert in Griffith and White (2023c) that their data on Berosus support the seven year gap in the division scenario. The authors claim that the division plan was activated twice. The existence of the plan, dual planning sessions, and dual activations are expansions on the biblical text but not disallowed by it. However, the proposed activation of the plan has some quirks. The initial departure includes only the Chinese and Peruvians with no explanation provided regarding the reason or timing. The Chinese are tied to the date of 2197 B.C. by associating Yáo with Noah and noting that a successor named Yǔ may have begun to reign in 2197, which is addressed in a separate section below. The Peruvians seem to be tied to 2197 by their duration, which will be discussed shortly. The division plan was activated for the main body seven years later when God intervened with the confusion of tongues. Based solely on the biblical text, one would assume that no significant dispersion occurred before the confusion of tongues.

Griffith and White (2022b) list the following duration endpoints concerning the Dispersion:

- Duration 13: The Reign of Yu of China: 2197 B.C.

- Duration 14: The Founding of Sicyon: 2089 or 2076 B.C.

- Duration 15: The Founding of Trier, Germany: 2053 B.C.

- Duration 16: The Colonization of Ireland: 2035 B.C.

- Duration 17: The Colonization of Peru: 2198/7 B.C.

- Duration 18: The Founding of India

We will deal with the reign of Yǔ in detail in a later section. The only other duration that seems completely out of hand is Duration 17, which posits a date for colonization of Peru seven years before the confusion of tongues as calculated in Griffith and White (2022b). According to Griffith and White’s source text, Viracocha (an Incan god whom they equate to Noah; this is a lot like equating Noah to Yáo; see below) led the colonizers to Peru and showed them the land they were to inhabit. Also, the authors posit that both the Peruvians (Duration 17) and the Chinese (Duration 13) left seven years before the confusion of tongues for unknown reasons and travelled practically overnight to regions hitherto unknown, one of them literally at the ends of the earth compared to western Asia. One wonders that if they were the first to leave why either party would travel so far. Only being assigned to a specific parcel of land makes sense of that part.

For Peru in particular, this speed of travel seems highly unlikely, even with a land bridge across the Bering Strait, and the land bridge may not have existed when needed for this scenario.2 On Oard’s (1979, 1990, 2024) Ice Age timeline, this land bridge would have been available from c. 200 to 600 years post-Flood. On the MT timeline, that would be 2147 to 1747 B.C. Hence, on the MT timeline, there was no path to Peru by land c. 2197 B.C. On the Snelling and Matthews (2013) Ice Age timeline, the Ice Age would have been from near Peleg’s birth in 2250 B.C. to about 1950 B.C., which also might not have provided a land path to Peru in 2197 B.C. This would have been only 57 or 58 years into the glacial buildup on their timeline. The Ice Age would have affected durations 15 and 16, also. The Ice Age under Oard’s model or Snelling and Matthews’ model would have prevented habitation of northern Europe until during or after the glacial meltdown. The earliest possible dates of settlement would be c. 1750 B.C. under the Oard model, or c. 2000 B.C. under the Snelling and Matthews model. These dates are not consistent with Durations 15 and 16. See Tweedy (2024).

Durations for the Founding of Babel

Another area of discussion is the use of durations and triangulations (Griffith and White 2022a) to pinpoint the date for the founding of Babel. Multiple durations cited by Griffith and White pertaining to the founding of Babel are based on sources written up to 2,000 years after the postulated date of this founding. These sources appear to refer only to Babylon, not to Babel. This mystery can only be solved by including a separate paper by Griffith and White published coincidentally with Griffith and White (2022b). In this separate paper (Griffith and White 2021), they argue for Babel to have been in Subartu in upper Mesopotamia and equate it to a city that was known by Sargon of Akkad as “Babylon”:

In this paper we will present evidence suggesting that there were two Babylons, though not in the sense of Hislop. The Babylon of Nebuchadnezzar was the second Babylon, in a similar sense that the York on Manhattan Island is New York, not the original York in Northern England. There are biblical, historical, and archaeological witnesses that point to where the original Babylon lay. If we follow them, they point to a specific site which has never been excavated. (Griffith and White 2021, 69).

Clearly here and in other parts of that paper and in Griffith and White (2022a, 2022b, 2023a, 2023b, 2023c), Griffith and White indicate that they equate Babel to Babylon, but not to the traditional Babylon known in Iraq. However, some of their durations just may point to traditional Babylon in Iraq and not to old Babylon.

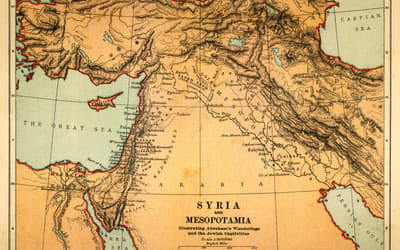

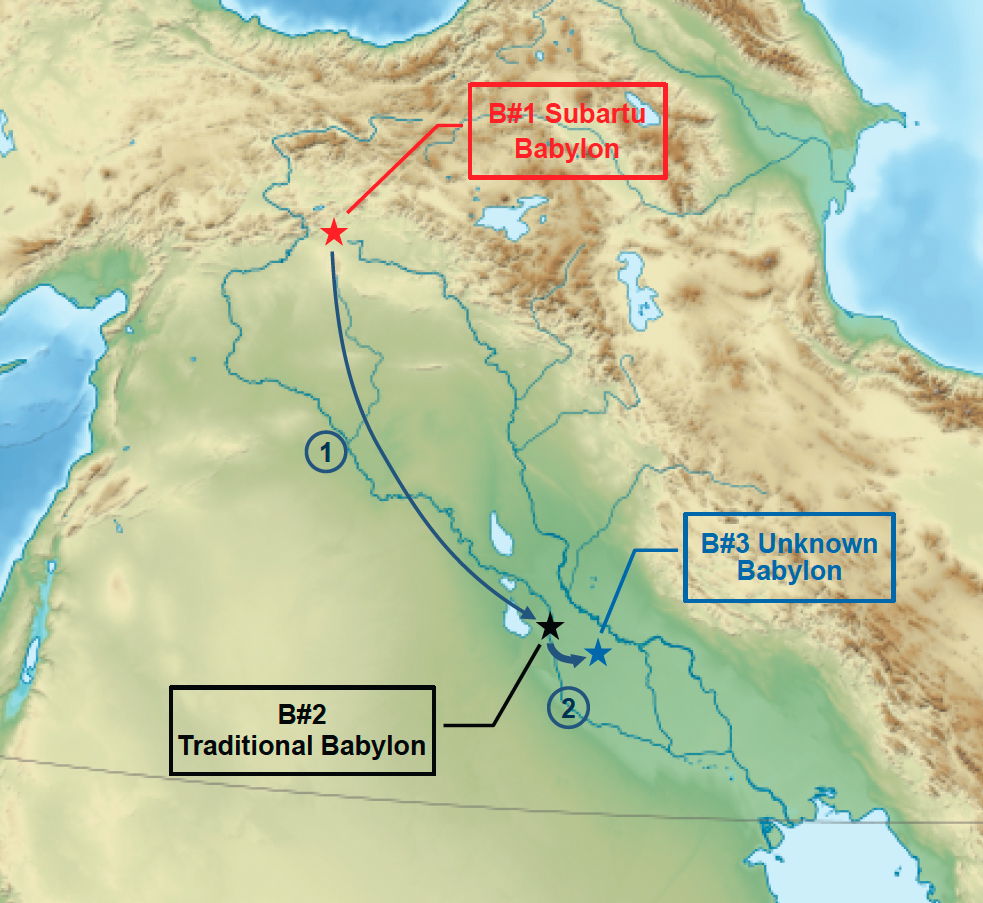

The reader may find it helpful to consult fig. 1. Based on a tablet called ABC 20, “Chronicles of the Early Kings” (Grayson 2000), Sargon conquered an area in upper Mesopotamia called Subartu. To humiliate Subartu, Sargon dug up dirt from the pit (of the altar perhaps) in a city of Subartu called Babylon, call it B#1, and moved the dirt to a “new” Babylon, call it B#2 near his capital of Akkad. This scenario is depicted as movement ① in fig. 1. Let us assume, as Griffith and White do, that this new Babylon (B#2) is actually the traditional Babylon of Nebuchadnezzar II and Berossus. Griffith and White (2021, 77) cite legends about Semiramis II conquering Akkad from the Gutian Arabs, discovering a shrine in front of the city of Akkad, and building a wall around it, which then became the city of Babylon (B#2).

Fig. 1. Possible moves of Babylon by Sargon of Akkad.

① Move from Subartu (B#1) to traditional Babylon (B#2) as assumed by Griffith and White.

② Move from traditional Babylon (B#2) to unknown Babylon (B#3) per Weidner Chronicle.

On a contrary note, Griffith and White also cite two sources (ABC 19, “Weidner Chronicle” [Grayson 2000] and “Curse of Agade” [Archi 2015]) that associate the desecrated Babylon with a temple called Esagila, which is known to have been in the traditional Babylon (B#2). That is, these latter two sources say that the dirt was moved from traditional Babylon (B#2) to a new Babylon (call it B#3) that was somewhere unknown to us and is now lost. This is depicted as movement ② in fig. 1. Considering the political overtones and anachronisms of these two sources, this scenario is very unlikely.

Some thoughts arise. Whether Sargon made movement ① or ② would not matter much to the analysis. Traditional Babylon (B#2) is the elephant in the room for all of Griffith and White’s sources. Griffith and White (2021, 77) make these statements:

The Weidner Chronicle and the Curse of Agade both interpret Sargon’s digging dirt from the pit of Babylon as being a sacrilege against the altar of the only Babylon they knew, whose temple was called the Esagila. That is the Babylon we know today [B#2], located south of Baghdad in Iraq . . . By the time that the Weidner Chronicle was written in the Neo-Babylonian Era after 606 BC, the original city with the Tower of Babel in Subartu had long been forgotten. (Emphasis and notations added).

If the original Babylon (B#1) had long been forgotten, how could anyone remember its founding? If the authors of those latter two ancient chronicles (c. 600 B.C. or earlier) only knew about traditional Babylon (B#2), we could not expect anything more or different from all those sources that Griffith and White cite to establish the founding of Babel: Callisthenes, Porphyry, Simplicius, Epigenes, Berosus, Philo, and Sanchonathion. Anything these people wrote about the founding of Babylon would refer to “the only Babylon they knew,” the traditional Babylon (B#2). So even if there had been a city in Subartu named both Babel and Babylon, that by itself would not prove that the durations go back to Babel. Likewise, finding the ruins of Babel in Subartu would not by itself mean that one had found the ruins of old Babylon (B#1).

With these thoughts in mind, let us look at three of the durations from Griffith and White (2022b) that they use to establish the date for the founding of Babel. In duration 1 in Griffith and White (2022b), which is labelled, “Callisthenes, 1,903 Years from Babel [sic] to Alexander,” they write,

Porphyry and Simplicius were two of the later teachers at Aristotle’s school of philosophy in Athens. They each recorded the tradition that Aristotle’s friend [great-nephew] Callisthenes, who was part of Alexander’s retinue, gained access to a library of astronomical observations in Babylon and had attempted to send a copy of them to Aristotle.

We are fairly confident that Aristotle’s great-nephew was sitting in traditional Babylon (B#2) when he wrote to his great-uncle about what he had discovered. One thousand, nine hundred and three years after the fact, he would not have been aware of an old Babylon (B#1). Alexander himself knew where new Babylon (B#2) was (he died there in 323 B.C.) but gave no hint that he knew about an old Babylon (B#1).

Griffith and White note that Callisthenes discovered “1,903 years of stellar observations contained on daily tiles.” That implies there were roughly 695,000 tiles (1903 × 365.242 ±). This figure does not include a century of observations posited by Griffith and White (2022b, Duration 19) to have been used by Noah and his family to predict the coincidence of the new moon with the vernal equinox in 2233 B.C., another 36,525 records that may or may not have existed at the time Callisthenes visited Babylon (#2). One wonders how Callisthenes thought he was going to copy all of those data and transmit them from Babylon (B#2) to Athens. We should not be surprised that the data never arrived in Athens. He may not have sent anything. He could have been considering making a synopsis, but to process 100 tiles per day would take 19 years with no days off to examine them all, and the result probably would be fraught with errors. Maybe he only wanted to send a sample set of copies, which is simple enough.

Taking everything at face value, nothing seems to indicate that anything but a single, uninterrupted series of astronomical observations was found, purportedly going back to the founding of the city from which Callisthenes wrote (B#2). If all of the observations had not been made in the new Babylon (B#2) where they were found, they would have consisted of two series, one from old Babylon (B#1) and one from new Babylon (B#2). Anything from before the move would have contained incompatible observations made from a point approximately 375 mi further north, a significant distance in making astronomical observations, and those would have to be separated to prevent confusion. Comparisons of the observations before and after the move would have shocked the observers by the differences in observed angles, so they would have noticed (and possibly drawn conclusions on the shape and size of the earth, as did Eratosthenes).3 These older records would have been very difficult to move intact from old Babylon (B#1) somewhere in upper Mesopotamia to new Babylon (B#2) in Iraq. According to Griffith and White (2021, 72), Sargon postdated the Dispersion by 500 years. That implies that to have a collection reaching back to the Dispersion and not before, approximately 183,000 daily tiles would have to be moved from B#1 to B#2. Sargon seems to have been interested only in desecrating an altar, not preserving astronomical observations, and there is no record of him moving any.

It would seem that this duration identifies the beginning of astronomical observations made and collected at the new Babylon (B#2) and probably nothing from old Babylon (B#1), indicating 1,903 years to the founding of new Babylon (B#2) as we know it in Iraq.

Now let us look at Duration 2, which is labelled, “Pliny–Epigenes, 720,000 [Days] from Babel [sic] to Berossus.” Moving on in time, we now have approximately 720,000 daily tiles, even more of a problem for capturing them and replicating them somewhere else. After Griffith and White address the meaning of the numbers, they make this very reasonable supposition:

Since Berossus dedicated his writings to Antiochus Theos (Ussher 2003, 364, §2826) it is reasonably assumed that the accession of Theos in 262/261 BC is the starting date. Adding 1,971 Julian years takes us back to 2233/2232 BC, with an error of ± 1.4 years. This also confirms the 1,903-year duration of Callisthenes.

According to Griffith and White, Pliny (c. A.D. 70) was quoting Epigenes (c. 200 B.C.), who was probably quoting Berosus (278 B.C.) or had access to the same records. As a priest of Bel, Berossus would have been aware of his city’s history, whether real or legendary, but writing 1,900+ years after the fact, he did not betray an awareness of an old Babylon. Otherwise, it is difficult to argue with this logic. This is what triangulations are supposed to do. The two durations bind together to provide strong evidence for the possible founding of Babylon (B#2) c. 2233 B.C. However, this triangulation may say nothing about Babel.

Let us turn to Duration 3, which is based on the writings of Philo of Byblos, “a pagan chronicler who lived in the time of Hadrian early in the second century” (Griffith and White 2022b, Duration 3). This source evidently came to us in Greek but was translated by Philo from Phoenician records written by Sanchonathion. The duration is labelled, “Babylon built 1,002 years before Semiramis II.” Assigning 1232 B.C. to Semiramis II (possible discoverer of the small shrine of Babylon in front of Akkad) then adding 1,002 years back to the founding of Babylon (not Babel) yields a year for the founding of Babylon (not Babel) of 2234 ± 5 years. There are no data saying that either Sanchonathion or Philo referred to any other Babylon than the traditional Babylon (B#2).

One alternative that would seem to solve the whole dilemma is to fall back on the thought that Babel should be equated to traditional Babylon (B#2), whose ruins are known to be at a certain place in Iraq. This conflation is common, seemingly based on the resemblance of the names of the cities in modern languages, but their etymologies are different. Babel by biblical warrant (Genesis 11:9) means confusion, and Babylon most likely means gate of the god(s). However, Griffith and White offer many convincing proofs that this thought is erroneous; they cite solid archeological, biological, and historical evidence. Among them, both Griffith and White (2021) and Habermehl (2011), although they use competing timelines and cite different scenarios, point out that the site of traditional Babylon (B#2) was probably under water when Babel was founded. It just might be that we have a whole lot of durations illuminating the history of Babylon (B#2) and little to none shedding any light on Babel.

Yáo is not Noah

This brings us to the other major area of comments, which is Griffith and White’s treatment of the ancient Chinese writings contained in the collection called the Shūjīng (Book of Documents, or Book of History). In Griffith and White (2022b), they discuss this subject under Duration 4, “The Co-reign of Yáo and Shun. 2277–2247 BC,” and again under Duration 13, “The Reign of Yǔ of China: 2197 BC.” The same data are summoned again to triangulate AP-28, “Second/Final Territorial Division: 2247 BC” in Griffith and White (2023b) and Griffith and White (2023c). The Chinese records of Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ in the Shūjīng, in coordination with the writings of Liu Xin (Griffith and White 2022b), do seem to lead to a strong synchronism with events in Genesis.

This apparent synchronism is strengthened by the identification of Yáo’s first year of rule with the end of the Deluge in 2347 on the MT timeline per Griffith and White’s calculations. Per Waltham (1971), Legge (1960) concludes that Yáo’s first year of reign was 2357, nine years before the start of the Deluge on the MT chronology, a reference acknowledged by Griffith and White. Considering this difference, their triangulations from Chinese data could be off by nine or ten years, which is not really significant in the scope of history, but also not quite so pat for their triangulations. Nevertheless, even taking the Griffith and White dates at face value, the synchronisms that they claim do not seem plausible.

The following sections cite heavily from ancient and modern Chinese sources. The author apologizes to any readers that might be offended or confused by the mixing of different Romanization systems of Chinese texts and names. In some cases, this is due to the author’s ignorance, but in others, it is the result of trying to be faithful to the translations given in the sources. As a result, the reader may find a mixture of Hanyu pinyin, Wade-Giles, and older Romanization systems herein. We have attempted to standardize on pinyin where possible. Also, the treatment of surnames and given names of Chinese authors in the professional literature seems not to be standardized, at least to this author’s knowledge. Any mistakes are the author’s, for which he is sincerely apologetic.

Did Yáo Exist?

Before starting, we should pause briefly to consider three issues. The first is whether or not Yáo as known from the Shūjīng ever actually existed. As we will see, Griffith and White equate Yáo to Noah. What we know about Noah comes from the Bible and is true. What we know about Yáo comes mainly from three ancient Chinese sources: the Shūjīng (Book of Documents, or Book of History [Waltham 1971] update of Legge 1960), the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian: Ssu-ma Ch’ien [pinyin: Sima Qian] 1994), and the Zhúshū Jìnián (Bamboo Annals [Legge 1960]). None of these Chinese texts is Scripture, so they have to be regarded somewhat skeptically. The first two sources are mostly in accord. The problem with the Zhúshū Jìnián is that between the two extant versions of the Annals, there are three separate portrayals of Yáo and his two immediate successors, Shun and Yǔ. We will explore this shortly.

Many scholars question both the historicity and political neutrality of all three of these sources. The historicity of these documents is an open question. Many scholars insist that documentary evidence is insufficient to remove the “legendary” label from figures like Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ, and from the Xia Dynasty. Some insist that without archeological evidence, the matter is moot. Tian, Ye, and Qian (2020, 105–137) cite only three reliable archeological sites that might have a bearing on this issue. Later we will discuss the possible evidence of an outburst flood investigated by Wu et al. (2016), who claim that the Xia Dynasty is represented in archeology by the Èrlǐtóu culture. The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project (Xueqin 2002) concluded that the Xia Dynasty was historical but appeared later in time than their traditional dates. The Project made no firm conclusions on the existence of Yáo and Shun. Legge (1960, 105–183 passim) seems to believe the Shūjīng is exaggerated but accepts the basic flow as historical. Altogether, behind every legend there is a reality that spawned it. Griffith and White explicitly acknowledge this by including not only the Shūjīng in their study but also by accepting many other ancient documents at face value.

Just one clue to the possible historicity of these documents is the fact that all three contain very specific, unrounded numbers for various events. For instance, the Shiji relates that Yáo named Shun his successor three years before abdication and retirement, and lived exactly 28 years after abdicating to Shun (Ssu-ma Ch’ien [Sima Qian] 1994, 10). Neither 3 nor 28 is a rounded number, like 30, which is often cited as the length of Yáo’s retirement instead of 28. All three of the Chinese sources are fraught with this kind of detail, which is characteristic of recalled fact, not identical but similar to this eyewitness statement from John 1:39: “(now it was about the tenth hour)” (NKJV). Another bit of evidence is that Wu (1982, 66–67, 467) claims that the astronomical data given in the Shūjīng are accurate enough to document c. 2200 B.C. as when the observations were made, which means they could have been made when Shun or Yǔ was emperor. Yáo is credited with setting up the observatories in the “four cardinal directions” (Waltham 1971). Nevertheless, even if Yáo never existed, we still will show in succeeding sections of this paper that, as he is described in the Chinese literature cited here, Yáo could not be simply a legendary version of Noah under a different label.

Regarding politics, some cite the fact that the Shūjīng was written during the Western Zhou Dynasty and might have been written to justify the rise of the Western Zhou after both the Xia and Shang Dynasties went through auspicious beginnings only to fall into moral decline (Shaughnessy 1999), a cycle reminiscent of the history of the Jews related in the Former and Latter Prophets. The Shiji was written during the Western Han Dynasty, which might have had different political ends, but the writings have the same outlook on the character traits of Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ as the Shūjīng. This tradition shared by these two documents, of holding up these three emperors as moral exemplars, seems to have been embraced by Confucians wholeheartedly (New World Encyclopedia n.d.) and to have influenced political ideals over many centuries. The Zhúshū Jìnián was written during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty between the times of the other two documents.

In no way disparaging the various authors or their intent, the proposition that any of these documents could be without political overtones is beyond reason, given that they are the human products of court scribes and official historians. Nevertheless, the main thrust of the Shūjīng is not one of politics per se but of the moral fiber of national leadership. The concept of the Mandate of Heaven embedded in both the Shūjīng and the Shiji, while having overtones of the divine right of kings, has as its most important practical implication justice in government, very similar to the Old Testament meaning of the Hebrew word mishpat (מִשְׁפָט), which on many occasions was lacking among the Jews.

A second issue addresses both the existence of and the possible dates for the Xia Dynasty. Based on calculations by Legge (Waltham 1971), the Xia ruled between 2205 and 1766 B.C., putting Yao’s first year of reign in 2357 B.C. Griffith and White (2022b, Duration 4) calculate the starting date for the Xia Dynasty as 2197 B.C. The Zhúshū Jìnián (Legge 1960, 183ff.) sets the founding of the Xia Dynasty in 1989 B.C. In 1996, the Chinese government commissioned the Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project (Xueqin 2002), which concluded that the dates of 2070 and 1600 B.C. were probable for the Xia Dynasty.

The dates from the Chronology Project, if taken as givens, would have two implications for this paper and for Griffith and White. First, the Project concluded that the Xia Dynasty existed, which would not be possible without the existence of Yǔ and his son Qi. That admission gives some small credence as well to the existence of Yáo and Shun. Second, the Project’s date for the start of the Xia Dynasty is 127 years later than the Griffith and White date, which moves the start of the Gun-Yǔ Flood 127 years forward in history as well. Moving the start of the Gun-Yǔ Flood from 2347 to 2220 B.C. basically shatters Griffin and White’s triangulation between Yáo’s ascension to the throne and the end of the Deluge on the MT timeline. The same result occurs for the “shorter Chinese chronology” (Legge 1960, 179–188) derived from the Zhúshū Jìnián.

The dates produced from the Chronology Project open up a variety of other explanations for the place of China in post-Flood history, avenues that are greatly in need of exploration. Our concern here, however, is to show that under the scenario painted by Griffith and White, we find ourselves in an intellectual cul-de-sac. Yáo could not possibly be Noah, as will be shown below. Griffith and White rely on the ancient Chinese records to establish the existence of Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ; and they constrain themselves to a more or less traditional timeline for those rulers’ regnal dates. We will take these assertions as givens below. What Griffith and White do not do is interpret the Shūjīng adequately or take all of the Far Eastern witnesses available into account.

A third issue is whether or not the Gun-Yǔ Flood actually happened. Chinese lore is rife with references to this massive flood described in the Shūjīng, where it consumes the careers of Yáo and Shun and propels Yǔ into heroism. It is embedded in the Chinese consciousness as the “Great Flood.” As previously stated, behind every legend there is a reality that spawned it. The annals that mention such a flood include the Shūjīng and the Shiji. The Zhúshū Jìnián, on the other hand, does not mention the Gun-Yǔ Flood except in the disputed jīnběn version (Hong 2021). Legge (1960) remarks on this situation and thinks it odd for the Zhúshū Jìnián not to mention the flood if it were recognized as historical when those annals were written, c. 300 B.C. Legge (1960, 176–183 passim) notes that the Zhúshū Jìnián just may be more realistic in portraying Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ not as emperors over a great realm with elaborate courts and Yǔ performing prodigious feats, but as instrumental tribal chieftains beginning work on a greater China. From his notes on the Zhúshū Jìnián, one would have to conclude that Legge was not convinced of the historicity of the Gun-Yǔ Flood, but the overwhelming sentiment is behind it. In a later section, we will discuss one possible paleo-geological discovery that some believe is proof of the Great Flood. If the Gun-Yǔ Flood was not historical, then Griffith and White would have to set this duration aside for reconsideration since Yáo would not be associated with a flood at all.

Chinese Literature and the Age of the Earth

Before delving into the Shūjīng, we first must acknowledge that the events and timelines in the Shūjīng and other ancient Chinese literature are meant to be understood in an overall Chinese view of history that does not conform to the MT timeline. The Chinese perspective is 2,000 years longer, longer even than the LXX. We should consider the calculations cited by Jones (1993) and ascribed by him to Bailly, who Jones states used Chinese data to derive the year 6157 B.C. for the beginning of the world. Jones also cites Bailly as computing 6158 from Babylonian data and Gentil computing 6174 from Indian data.4 These three dates are within 17 years of each other (two are essentially identical). Jones does nothing to refute these dates except to appeal to the MT. Griffith and White do not mention them. If one cares to look at these data points, they do support an alternative timeline of the world that leaves plenty of time for both the Genesis Deluge and the Gun-Yǔ Flood described in the Shūjīng. Rather than use Bailly or Gentil, we will consider as possible the LXX timeline, which is biblical.

Yáo Versus Noah

Griffith and White (2022b, Duration 4) calculate 2247 B.C. as the year in which two events took place. First, the Masoretic genealogies in Genesis 5 and 11 place the birth of Peleg in A.M. 1757 (A.M. stands for Anno Mundi, years since the creation of the earth), which is 2247 B.C. on the MT timeline. Second, the timeline generated from the Shūjīng and Liu Xin according to Griffith and White, in contradiction to Legge, places the beginning of the 50 year sole reign of Shun in 2247 B.C. after a 30-year coreign with Yáo. Griffith and White take the apparent synchronism of these two events as evidence that a major rebellion against Noah and his sons occurred or became outwardly known in 2247 B.C. Working backward, they calculate 2347 as the year in which Yáo began to rule, which is the year that the MT timeline posits for the end of the Deluge. Ignoring conflicts with Legge’s dates and taking these dates at face value, these data pose two questions: 1) What rebellion does the Shūjīng describe? 2) With those dates, how could Yáo not be Noah?

Griffith and White detect a rebellion against Noah in the Shūjīng based on detecting a rebellion against Yáo. Discussing Duration 4 (Griffith and White 2022b), they say, “The Chinese data . . . places [sic] the deposing of Noah 101 years after the Flood” (emphasis added). The Shūjīng in fact says nothing of the sort. The Chinese literature on this matter is similar in at least two of the documents cited above and is mostly supported by the third. The Shūjīng reads essentially the same as the Shiji in this regard. Neither speaks a word about rebellion against Yáo. Both indicate that Yáo employed Shun as a viceroy until advancing age forced him to abdicate in favor of his protégé after 70 years of rule. Yáo died in the year Shun assumed sole regency, and according to both documents, the people (not just Shun) mourned Yáo as they would a beloved parent for three years. This actually may have been a customary observance and not a heartfelt devotion, but the fact that it is reported is significant. It is doubtful that a deceased emperor who had been deposed and left to die in prison would be afforded much courtesy by his deposer (reflecting one of three versions of the story from the Zhúshū Jìnián discussed below). The usual course of action in such circumstances is to try to obliterate the memory of the deposed ruler from the land.

The situation with the Zhúshū Jìnián is more complicated. A total of three versions of the Yáo/Shun/Yǔ story were spawned from this source. The version translated by Legge (1960, 108–176), and the one he considered legitimate, matches the Shūjīng and the Shiji in terms of the relationships between the rulers but does not mention the Gun-Yǔ Flood. Another version5 analyzed by Hong (2021; the jīnběn version) is basically the same as the Shūjīng but portrays the characters somewhat less idealistically, or perhaps more realistically, in at least two cases. They indicate that on Shun’s request, Yáo ordered the execution of Gun (Kǔ) instead of banishing him to Yǔ Mountain for failing to stop the flooding (see below). Also, this version states that the reason Yáo finally abdicated was because Shun was being glorified by the people for vanquishing the flooding. Shun’s protégé Yǔ was actually responsible in all versions of the story that include the flood, and he received all the glory centuries later. This is reminiscent of Saul’s jealousy of David when David began to receive accolades for his military victories: “So the women sang as they danced, and said: ‘Saul has slain his thousands, And David his ten thousands’” (1 Samuel 18:7 NKJV). This second version states that Yao banished his own son. After Yao died, Shun tried to get the son to accept being successor to Shun but was refused. Afterward, Shun turned to Yǔ for a successor.

The third version is quite different, as pointed out by Tian, Ye, and Qian (2020, 108–109). This version of the story states that Shun overthrew and imprisoned Yáo, who died in prison. Then Shun banished Yáo’s son and rightful heir whom Shun later defeated in battle. Taking Shun’s lead, Yǔ subsequently overthrew Shun. Legge (1960, 116 note 8, 177) states that this story was not actually a part of the original Bamboo Annals but was incorporated accidentally from ancillary materials found at the same time that the Zhúshū Jìnián was recovered from King Xiang’s tomb. This version omits mention of the Gun-Yu flood.

All versions of the story portray Shun as successor to Yáo. Confucianism holds up Yáo’s purported decision to name Shun over his son Ju as successor as a very noble and patriotic sacrifice, putting the welfare of the people above that of his own family, for which Yáo is venerated: “Yao said, ‘In the final analysis, I will not displease the people and benefit a single person’” (Ssu-ma Chi’ien [Sima Qian] 86 1994, 11). Griffith and White seem to consider that the coregency with Shun suggests that Yáo’s subjects (Noah’s descendants, actually) had rebelled against him (against Noah and his sons, actually). However, a ruler naming a coregent as he ages is not necessarily a sign that the people or nobles are dissatisfied with his leadership. Coregency is nothing but sound succession planning that may prevent a civil war. Habermehl points out that ancient Egyptian rulers frequently formed coregencies with their adult children (Habermehl 2013a, 2013b).

Griffith and White obviously equate Yáo to Noah as seen above, and by ascribing certain post-Flood activities to Noah that do not appear in the Bible but do appear for Yáo in the Shūjīng. This is discussed below. Given the dates ascribed to Yáo and to the Deluge by Griffith and White, what else is possible except for Yáo to be Noah? No one else could be “emperor” at this stage of the world. According to the MT timeline, only eight people would have been alive in 2347 B.C., and Noah was their Patriarch. The clear implication of these MT dates against the Chinese records yields a three-way choice: either 1) Noah and Yáo must be the very same person, or 2) the Griffith and White dates for Yáo are wrong, or 3) the MT date for the Deluge is wrong. To examine this quandary, let us start by comparing Yáo to Noah at the detailed level using the Shūjīng, the Shiji, and the Bible.

The identification of these two personalities, Yáo and Noah, leads to some awkward conclusions. For instance, Yáo is listed in the Shūjīng and the Shiji as the great-great-grandson of Huang Di (⿈帝), which translates as “Yellow Emperor.” Based on writings by Hamilton (1820), Griffith and White equate the Yellow Emperor to Enosh (2023b AP-31) and determine his death to have occurred in 2805 B.C. According to Martino Martini, a seventeenth-century Jesuit, the dates of Huang Di’s reign were 2698/7–2598/7 B.C. (Mungello 1989). Ostensibly, this is the same Yellow Emperor that according to the Shiji united a number of tribes and fought the Battle of Zhuolu against rebels (c. 2500 B.C.), forcing his opponents south of the Yangtze River, and creating the incipient nation of China. This same Yellow Emperor is recorded in Vietnamese Hmong oral traditions as the one against whom the Hmong (or Miao, referred to as the San Miao (three Miao) in the Shiji) rebelled in ancient times (Savina 1924b). Aside from the obvious lack of Chinese context, the generations do not line up. Enosh is three more generations removed from Noah than the Shūjīng genealogy of Yáo allows. Enosh’s great-great-grandson would have been Enoch, three generations earlier than Noah.

Following Enosh just for the moment, Griffith and White (2023b, “Durations to Creation” and AP-31) cite a collection of dates and cycles described by Hamilton (1820) that lead to MT compatible results for the death of Enosh and from there to the date of Creation. Using Hamilton’s data, they calculate Creation as 4003 B.C. one way and 4005 B.C. another. The issue is that the only data equating Enosh to Huang Di seems to be Hamilton’s claim that they were the same, which also seems to be what he was seeking to prove.

In the Shiji, Huang Di is listed among the Five Emperors, as are Yáo and Shun:

The Five Emperors were legendary, morally perfect sage-kings. According to the Records of the Grand Historian [Shiji] they were: The Yellow Emperor (黄帝), Zhuanxu (顓頊), Emperor Kǔ (帝嚳), Emperor Yáo (堯), and Emperor Shun (舜). Yáo and Shun are also known as the “Two Emperors,” and, along with Yǔ the Great (禹), founder of the Xia dynasty, were considered to be model rulers and moral exemplars by Confucians in later Chinese history. (New World Encyclopedia n.d.; cf Birrell 1999 and Ssu-ma Ch’ien [Sima Qian] 1994.)

Instead of aligning them with the antediluvian Patriarchs per Hamilton, some researchers align the Five Emperors with the Patriarchs from Shem to Peleg (for example, Nelson and Broadberry 1990). However, neither of these alignments is likely. We will see below that the Miao oral tradition (Truax 1991, cf. Cooper 1995; Hattaway 2018; Savina 1924a) gives evidence that Yáo follows Noah by approximately 12 generations.

There are many other reasons to doubt the identification of Yáo with Noah. First, Genesis 9:28 states that Noah lived 350 years after the Deluge ended, while the Shūjīng states that Yáo lived only 100 years after his flood started. Also, if the synchronism generated from the Shūjīng correctly aligns Yáo to Noah, we would expect Yáo’s career to look remarkably like Noah’s, and for Shun and Yǔ to have easily identifiable biblical counterparts. Starting with Yáo, his career in the Shūjīng bears no other resemblance to Noah apart from the mention of a flood. The Shūjīng makes no mention of the Ark; other Far Eastern sources mention the Ark as part of the Deluge story without mentioning Yáo (see below). That would be a pretty significant thing to associate with an ancestral ruler one wanted to glorify and/or deify.

No mention is made of confusion of tongues or dispersion in Yáo’s time or in that of Shun, Yǔ, or any other ruler in the Shūjīng. However, the Shūjīng does give explicit indications of post-Dispersion culturally exclusive attitudes in the time of Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ, which according to Griffith and White would be some years before the Dispersion. The Shūjīng speaks of insiders: the “black-haired people,” and outsiders: both the “barbarous tribes” (maybe the Mongolians and some eastern Chinese tribes) and the Miao (“who would not submit”). These insider/outsider words express post-Dispersion attitudes, not the attitudes of people who are desperate to cling together and make a name for themselves like Noah’s descendants at Babel. The Miao are described in the Shūjīng as those “who would not submit” because they defied the central Chinese authority, starting with their rebellion against the Yellow Emperor at Zhuolu as described in the Shiji. The Miao are critical to understanding this history, and they will be addressed more fully below.

Likewise, the Bible does not discuss draining the land or setting up observatories to synchronize calendars as does the Shūjīng; nevertheless, Griffith and White imply that based on the extra biblical witness of the Shūjīng, we know of two of Noah’s post-Flood career fields, one being flood controller, the other being astronomical observer. As to the latter, in Griffith and White (2022b, Duration 19) they write, “Noah and his family must have been making precise astronomical observations for over a century prior to the founding of Babel in order to be able to predict the coincidence of the new moon and vernal equinox of 2233 B.C.” (This is another century of observations posited in addition to the 720,000 days reported by Epigenes in Griffith and White (2022b, Duration 2.) As discussed above, we might consider that the founding of Babylon in Iraq, not Babel in Subartu, was associated with this astronomical coincidence.

Returning to the Chinese rulers and Noah, no known biblical figures have careers remotely similar to Shun and Yǔ, not only in respect to draining the land from a flood, but especially regarding succession of rulers. The first king mentioned in the Bible (apart from God) is not Noah but Nimrod, which clearly was a usurpation of God’s rule and not a planned and orderly succession as described for Yáo to Shun, from Shun to Yǔ, and from Yǔ to Qi in the Shūjīng. The description of succession also points out the locus of the rulers. If rule passed from Noah to Shun, we might expect something to appear in Scripture unless Shun were completely removed from the biblical story, such as by being in China, which would imply that Noah/Yáo was also in China. The Shūjīng implies that all three of these Chinese rulers had a chain of personal contact at least until Yáo’s abdication, which implies they were all in China.

According to the Shūjīng, Yǔ’s success led Shun to name Yǔ as his successor. According to both the Shūjīng and the Shiji, abdication6 rather than inherited rule lasted from Yáo until Yǔ; then Yǔ and his son Qi went on to found China’s first dynasty, the Xia Dynasty. Now, “dynasty” implies parent/child relationships if not primogeniture. The plain implication of these successions by abdication is that Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ were not closely related by blood, which could not have been possible just after the Flood. Immediately after the Flood, everyone on earth was closely related to Noah except possibly for the four women who came off the Ark. Also, the Shūjīng states that Yáo passed over his own son Ju in favor of Shun because they had opposing characters, Ju being obstreperous and indolent and Shun being noble. Shun was renowned for having been loyal to his parents and younger sibling in a very difficult family situation. One might ask to which of Noah’s three sons Ju would correspond.

In the Shūjīng, draining the land from the Gun-Yǔ Flood occupies much of the official careers of these three Chinese rulers, something the Bible never mentions. The Shūjīng says that Yáo had a minister named Kǔ, not to be confused with Yáo’s predecessor in the line of Five Emperors. This minister Kǔ is also called “Gun” in many renditions of this lore, hence the appellation Gun-Yǔ Flood. Kǔ tried unsuccessfully for nine years to control the flooding. Finally, Shun, near the beginning of his coreign with Yáo, banished Kǔ to Yǔ Mountain for life (according to one version of the story, Yáo ordered Kǔ’s execution), and then appointed Kǔ’s son Yǔ as Shun’s replacement minister to solve the flooding problem (which is hard to imagine if Yǔ’s father had been beheaded). Note that in the Shūjīng, Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ all have ministers and advisors, something never mentioned in Scripture for Noah. Ultimately, Yǔ was successful. The Shūjīng states that Yǔ declared his final success in the eightieth year of Yáo’s reign, making the Gun-Yǔ Flood an 80+ year event. Granted, the aftermath of the Deluge could have lasted centuries beyond the grounding of the Ark, so this is not to deny the possibility that the Gun-Yǔ Flood was part of the aftermath. This possibility is discussed further below.

Most modern scholars say that Yáo was absorbed with fighting flooding of the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers in China (Wee 2021; Wu et al. 2016; Yang, An, and Turner 2005). The Yellow River, which floods catastrophically about four times every century, continues to threaten lives during seasonal flooding, as recently as July, 2021. The Gun-Yǔ Flood is recalled when it happens (Wee 2021). The description of the Gun-Yǔ Flood in the Shūjīng is somewhat hyperbolic, describing the flooding as catastrophic and affecting all of their world, that is, the Nine Regions (Waltham 1971, “The Tribute of Yǔ”). One might say that the two river basins, a huge land area, was their whole world at that time, but identifying this flood with the Deluge—literally worldwide and fathoms above the highest peaks—would be more than the Shūjīng or the Shiji texts warrant. For one thing, the population of the world was not wiped out by the Gun-Yǔ Flood according to either source. A number of (not closely related) characters in these sources came through the beginning of the Gun-Yǔ Flood to play parts in the ensuing struggle, and the Chinese, at least, clung to life and land through the flood by living in the mountains and sometimes in trees (Waltham 1991). As mentioned earlier, Legge (1960, 176–183 passim) believes the entire story is exaggerated if not suspicious altogether.

Not being the Deluge, the Gun-Yǔ Flood may have been a regional disaster. Evidence for a massive regional flood in the respective part of China has been found and is estimated by geologists as dating to ca. 1920 B.C. (Wu et al. 2016). The scenario painted for this flood by geologists sounds a lot like that portrayed for the creationist view of the forming of the Grand Canyon by spillover (Austin, Holroyd, and McQueen 2020) or the formation of the scablands in the Pacific Northwest (Bretz 1923; Waitt 1985). A natural dam bursts and the damage downstream is horrific, according to Wu et al (2016). Apparently, there was huge loss of life from this flood testified by human remains found buried in its sediments. The dating of this flood is separated from the MT date for the Deluge by hundreds of years, but it is roughly compatible with the Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project dates (Xueqin 2002) for the Xia Dynasty. Wu et al. (2017) disputes the age of the geological flood in question, putting it no later than 5,600 years before present, or approximately 3600 B.C., but possibly up to 8,000 years before present. These earlier dates would not fit the MT timeline, and only 3600 B.C. could be accommodated by the LXX.

Under the “outburst flood” scenario, the Gun-Yǔ Flood probably would have been caused by a natural dam being destroyed by an earthquake. An exacerbating factor could have been successive years of seasonal flooding, or runoff from glacial melt (see below). An even more intriguing possibility is the terrestrial impact postulated by Dodwell to have occurred in 2345 B.C., discussed at length by Faulkner (2013). A negative that undercuts Wu’s explanation (Wu et al. 2016) is that an “outburst flood” might last for a season, or even a few years if prolonged by other factors, but probably not for 80 years. Wu et al. may have discovered a disastrous but punctuated regional flood, not the Gun-Yǔ Flood.

Under the LXX timeline, the Gun-Yǔ Flood would be less likely to be a direct result of the Deluge, occurring many hundreds of years after. However, it could have been an indirect result of the Deluge. Habermehl (pers. comm. January 25, 2024) posits that the Gun-Yǔ Flood may have been a consequence of the post-Flood Ice Age glacial meltdown, which would be consistent with an 80 year flood and with other ancient reports of a flood c. 2350 B.C., such as Ogyges Flood (Africanus 2019; Weaver et al. 2003).

According to the Shūjīng/Liu Xin dates calculated by Griffith and White, Yǔ founded the Xia Dynasty in the year 2198/2197, based on 1,421 years (sum of dynastic rules) before the solar eclipse of 776 B.C. (Griffith and White 2022b). Legge (Waltham 1971) computes the year of Shun’s death as 2205 B.C., a little earlier, and 2197 as the year in which Yǔ’s son Qi rose to the throne. The Zhúshū Jìnián asserts that Yǔ rose to the throne in 1989 B.C., a date regarded by Legge (1960, 179–181, 184) as unreliable. Regardless, this date of 2198/7 is six or seven years before the Dispersion as calculated by Griffith and White (2022b). To grant that this date for the founding of the Xia Dynasty is accurate implies one of two things.

The Chinese firmly believe that Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ (if they existed) ruled in China, not Mesopotamia. The discussion above regarding succession places all three rulers in China, not Mesopotamia. Beyond that, the Shūjīng gives many names of mountains and rivers that scholars such as Legge, Carrithers, and Waltham (Waltham 1971) aver as identifying specific locations in China. In addition, the Shūjīng states that Yáo was from the province of Tang (hence his surname) and served there as a regional governor (an office never mentioned for Noah for whom it would make no sense whatsoever), and Shun was from the province of Yǔ, both of which have been assigned locales in China by the same authorities. In that case, these three rulers were in China—including Noah—several generations before the Dispersion as calculated by Griffith and White, which, unless Shinar actually was somewhere in China, would violate the biblical text.

Alternatively, if they were not in China, then these three rulers were trying to channel rivers and drain marshes somewhere on the Plains of Shinar in western Asia. That seems to be equally unlikely, not because it could not flood in Shinar, but because Noah’s family would be foolish to settle there if that place was still under water from the Deluge. Might they not just stay in the foothills of Ararat (or Cudi, a proposed landing place for the Ark; see Conybeare 1901; Crouse 1992; Habermehl 2011), or at least look for a drier place in another direction? Actually, the biblical narrative states that Noah and his family waited in the Ark until the earth was “completely dry” (Genesis 8:14, NKJV). According to the Miao oral tradition, “The mud was confined to the pools and the hollows” (Truax 1991). “Completely dry” probably means at least “not continually under water.”

Other Ancient Chinese Witnesses

The following discussion reflects in a cursory manner on Chinese lore of the Creation and Flood (see for example, Birrell 1999; Christie 1998; Lewis 2006; Yang, An, and Turner 2005), lore that recalls times long before events described in the Shūjīng in the Chinese scope of history. In these sources, we find that any character in Chinese lore who looks like Noah has no connection with Yáo. The tales of Fuxi must be considered. There are various creation and flood tales from different parts of China and different ages that name Fuxi. One identified by Nelson (1931) is described on the Answers in Genesis Web site:

The Chinese consider Fuhi [Fuxi] to be the father of their civilization. He, his wife, three sons, and three daughters [daughters-in-law?] escaped a great flood. They were the only people left alive on the whole earth. After the flood, they had many children from whom the whole earth was repopulated. (Answersingenesis.org 2016)

It has been noticed that this story does not mention the Ark. This is only one instance of the name Fuxi in Chinese lore, and related personalities can be confused easily. Fuxi is seen here as Noah but is seen in other lore as either Noah or sometimes as Adam as below, or even as a creator god with his consort goddess, Nǚwā.

The goddess Nǚwā (女媧) is another figure in Chinese lore that may bear on this matter. In various legends, some of which are related in the Huainan-Tzu [pinyin: Huainanzi] (ca. 139 B.C., see Damascene 2004), the goddess Nǚwā made several repairs to the universe following a rampage by two battling gods. The destruction of the Pillars of Heaven caused great flooding and many other catastrophic events. She replaced the Pillars with giant tortoise legs, thus ending the physical calamities, and repaired a hole in the sky by filling it with five-colored stones, which one has to admit is very evocative of Genesis 9:13. Other stories of Nǚwā tell of her creating mankind out of yellow clay (nobles) and brown mud (common people). In these stories, Nǚwā acts in god-like ways, but the stories of Creation and the Deluge are apparent. In all these stories, Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ play no part.

Other stories tell of Fuxi and Nǚwā being created as the first man and woman on earth, in some stories as twin brother and sister, in others as consorts. These are more Adam and Eve-like roles, but we must note this similarity: Adam and Eve first populated the earth; then Noah and his wife repopulated the earth. There is enough room there for substitution in either direction. Griffith and White equate Fo-hi or Fo-xi with Adam (2023b: AP-30), again perhaps in response to Hamilton (1820). In various tales, Fo-xi could be either Adam or Noah, depending on context.

For the moment, we must consider this: neither Yáo’s personal narrative nor his name ever come up in these myths and stories of the Creation and the Deluge. The Chinese do not seem to have identified Yáo with Noah in any way, and they certainly were aware of the Deluge story and considered it separate from the story of the Gun-Yǔ Flood.

The Bible in a Far Eastern Poem

The strongest evidence about how Yáo fits into post-Flood history comes from another Far Eastern source, the oral tradition of the Miao people (Truax 1991; cf. Cooper 1995; Hattaway 2018; Savina 1924a). The Miao people (sometimes called Miautso or Hmong) are a minority in China who seem to have come to China through Mongolia from above or near the Asiatic Arctic Circle (Hattaway 2018, 18; after Quincy 1995, 18ff). They seem to have inhabited parts of China until subjugated by the Han Chinese (an event that is celebrated in the Shūjīng), after which they were driven into southern China and Indochina. They were part of the losing opposition to the Yellow Emperor at the Battle of Zhuolu according to the Shiji. Most U.S. citizens are aware of this people group from our experience in Viet Nam, where they are known as Hmong. The Hmong in Viet Nam remember their rebellion against the Yellow Emperor (Savina 1924b). The fractious relationship of the Miao (“who would not submit”) with the Chinese (the “black-haired people”) in the Shūjīng has already been noted.

The Miao oral tradition is poetry that is recited at funerals and weddings to identify the progenitors of the subject persons all the way back to Adam. The poem covers the story of creation, the forming of Adam from dirt (he is called the “Man of Dirt,” or simply “Dirt,” which is to say, “Adam”), the separation of Eve from Adam, the pre-Flood Patriarchs starting with Seth going down to Noah (with some gaps), then going beyond the Flood. The primary descendants of Noah’s sons are listed, and in the Miao lineage, the poem starts with Japheth and Gomer, which makes them of the Indo-European stock.7 The poem relates the Deluge, Babel, the Tower, confusion of languages, the Dispersion, and the entire Miao lineage from there forward.

The poetry includes some details, like the names of some Patriarchs’ wives, not recorded by the Hebrews. The tradition does not seem to include the Fall nor Cain and Abel. Also, some of the Patriarchs between Seth and Lamach are missing or have names that cannot be aligned easily. Truax (1991) has established the antiquity of the Miao oral tradition and that it predates missionary influence (cf. Cooper 1995; Hattaway 2018; Savina 1924a). The accuracy of transmission of this poetry is enhanced not only through metrical lines, but also through couplets that repeat facts in different words, like the parallelisms in Hebrew poetry.

In the Miao tradition, Nuah quite clearly is the biblical Noah, and his spouse is named Gaw Bo-lu-en. Their sons’ names are listed as Lo Han, Lo Shen, and Jah-phu. If you like, you may read these names as Ham, Shem, and Japheth. Most of the names in the Miao poetry have easily recognizable counterparts in the Hebrew Scriptures. Both sources tell the same story, albeit in different idioms. The Miao story of how Noah, his household, and animals in mated pairs survived the Deluge in a “ship very vast” almost completely rehearses the story told in Genesis 6–9, right down to the reconnaissance dove and the sacrifices after grounding. The Miao story omits the rainbow (Genesis 9:13).

This same Miao oral tradition gives very strong support to the premise that Noah and Yáo were completely separate persons in space and time. The tradition states that the Miao first had contact with the Chinese eight generations after Noah and the Flood (see Cooper 1995, Appendix 12 for a graphic illustration). In one section, the poetry lists seven generations from Japheth to Seageweng and Maw gueh, parents of 11 children each of which founded a tribe. Five tribes became the Miao, and the other six tribes intermarried with the Chinese, which would have been about the time of the Yellow Emperor or a little before according to the Shiji. Yáo, as the great-great-grandson of the Yellow Emperor, would have come four generations later. Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ could not have been contending with the Miao until after the Miao (“who would not submit”) and the Chinese (“the black-haired people”) had collided, which was at least eight generations after Noah, making Yáo about 12 generations after Noah.

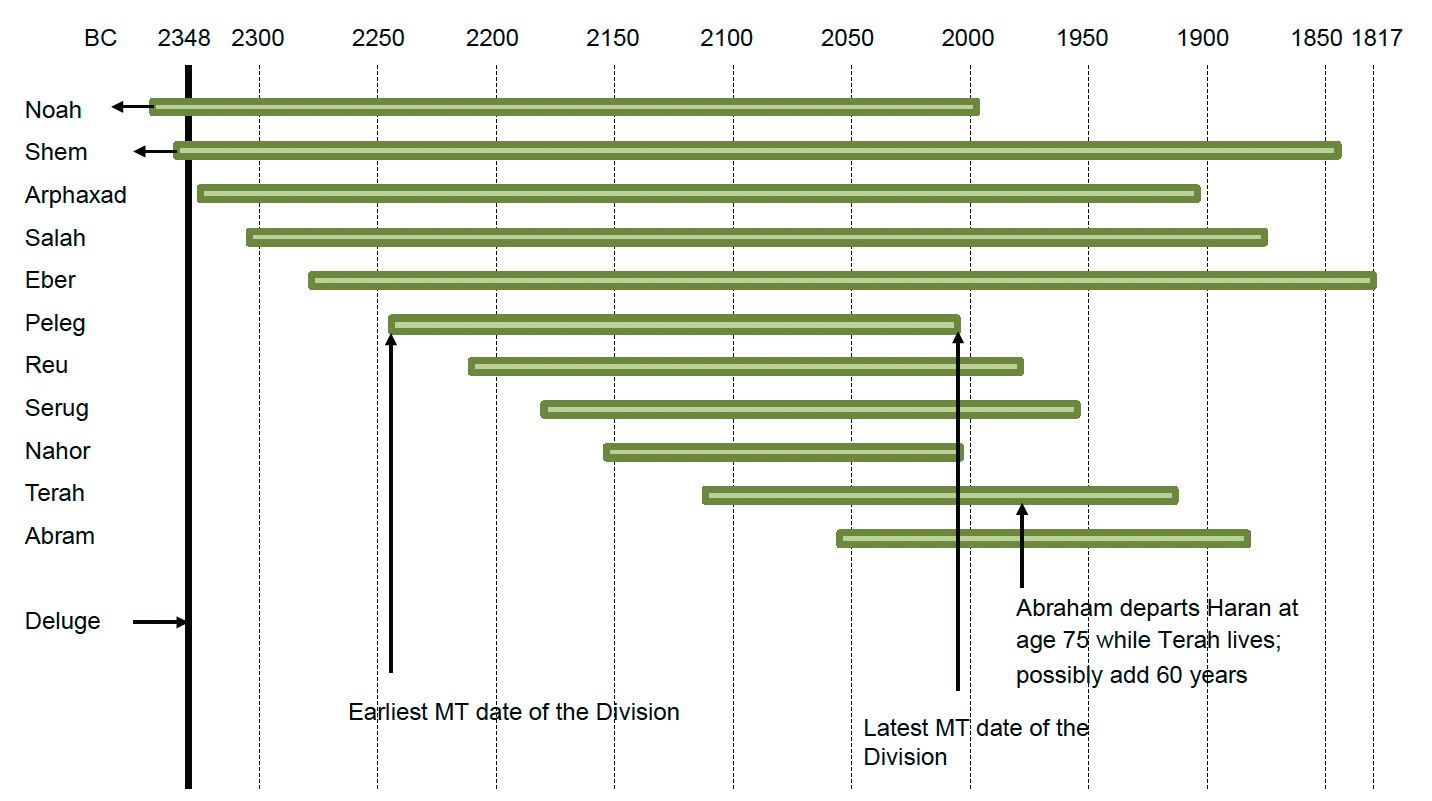

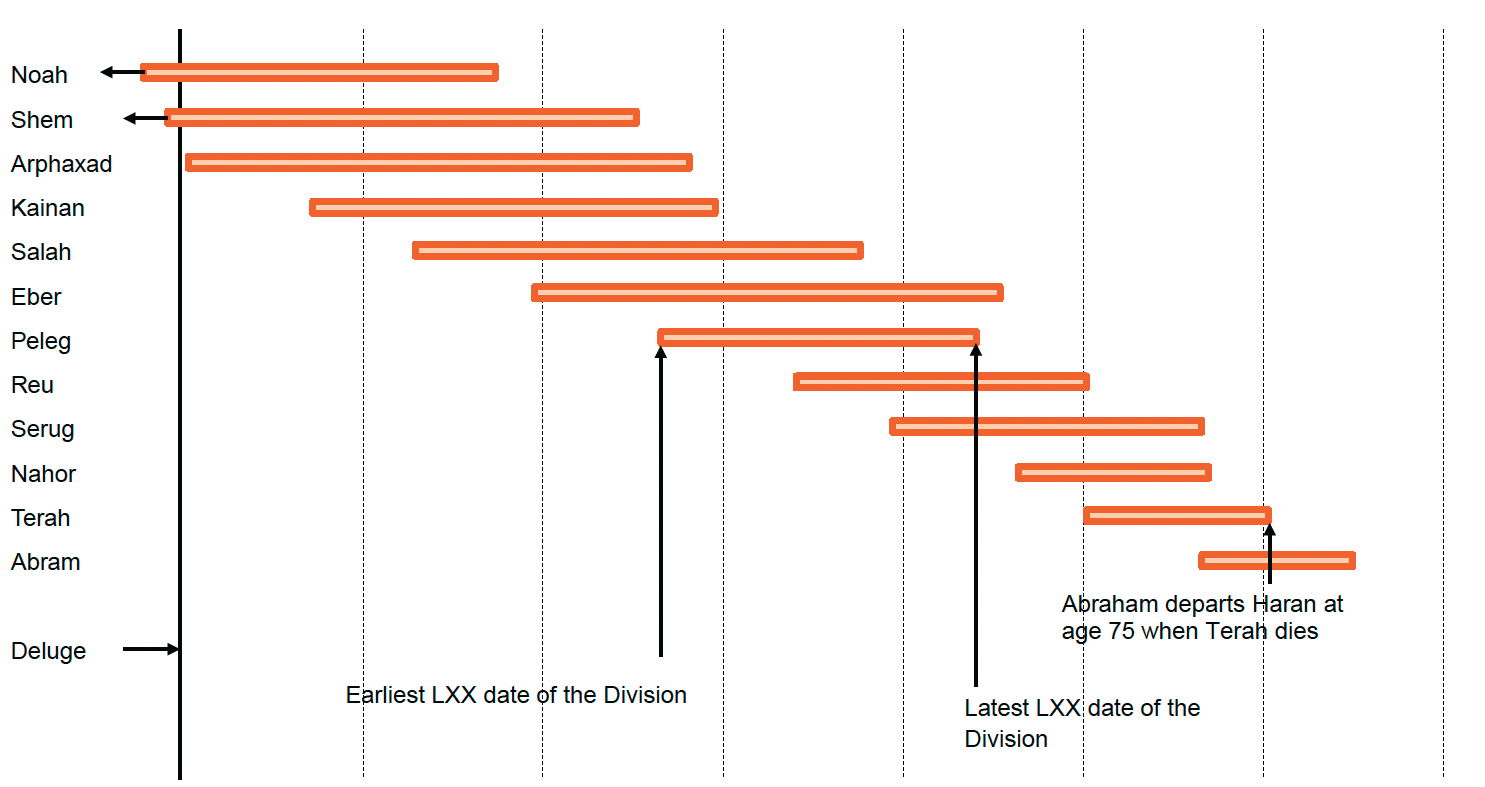

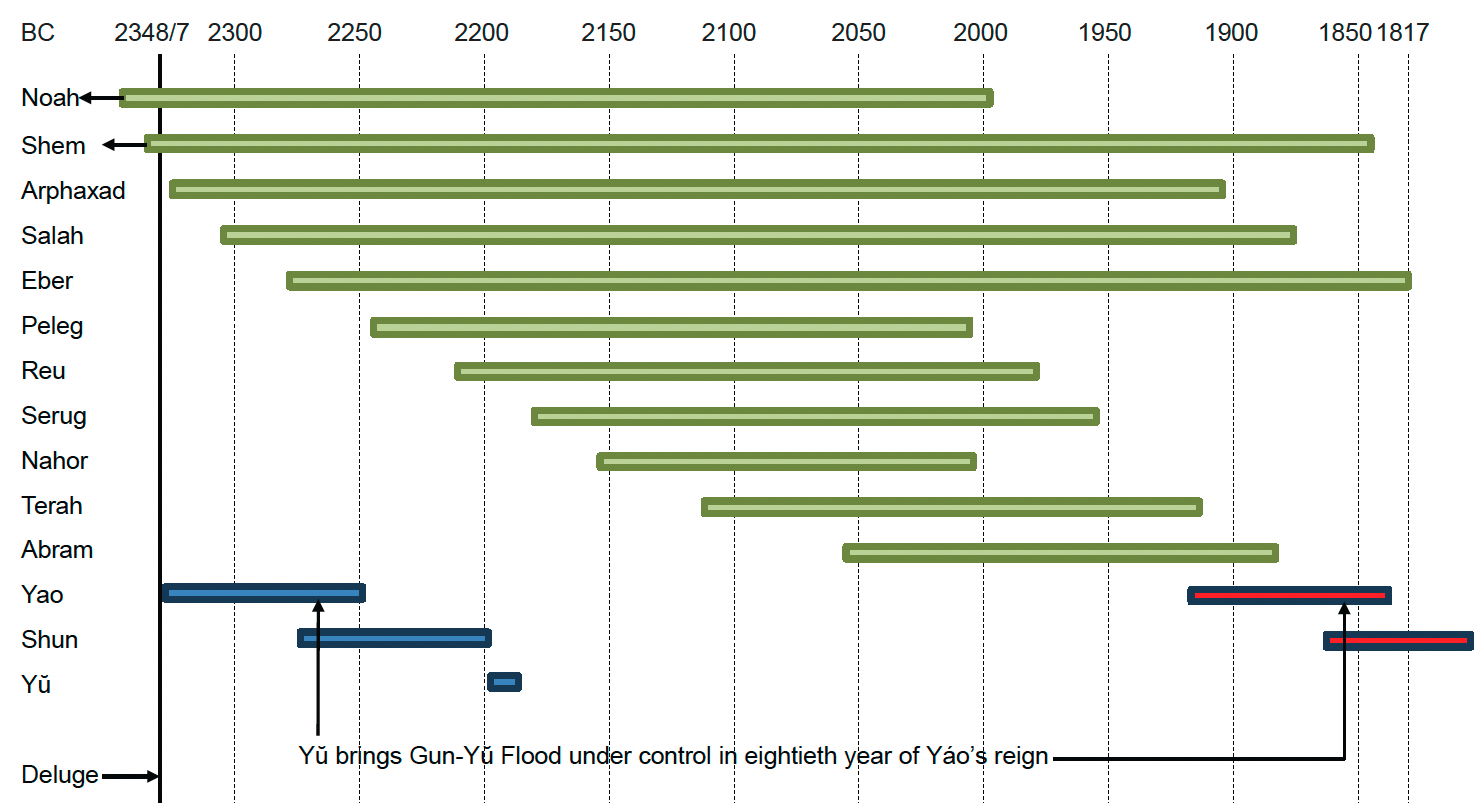

This conclusion, that Noah and Yáo are separated by about 12 generations, can be illustrated by placing Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ on the timelines of the Patriarchs. table 1 and figs. 2 and 3 show a selected version of both the MT and LXX timelines.8 Fig. 4 shows that placing the three Chinese emperors on the MT timeline using Griffith and White’s dates leads to the muddled situation just discussed at length. Placing Yáo and Shun on fig. 4 in accordance with the geologists’ estimate of 1920 B.C. for the outburst flood (Wu et al. 2016) seems reasonable until we note that no other ancient Chinese data place the reigns of these emperors or the Gun-Yǔ Flood this late in history, including the data relied on by Griffith and White (2022b, Duration 13). However, this figure is close to being compatible with the Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project dates (Xeuqin 2002), which place the beginning of Yu’s reign in 2070 B.C., and slightly closer to the Zhúshū Jìnián date of 1989 B.C. for the beginning of Yu’s reign, but neither match is very good.

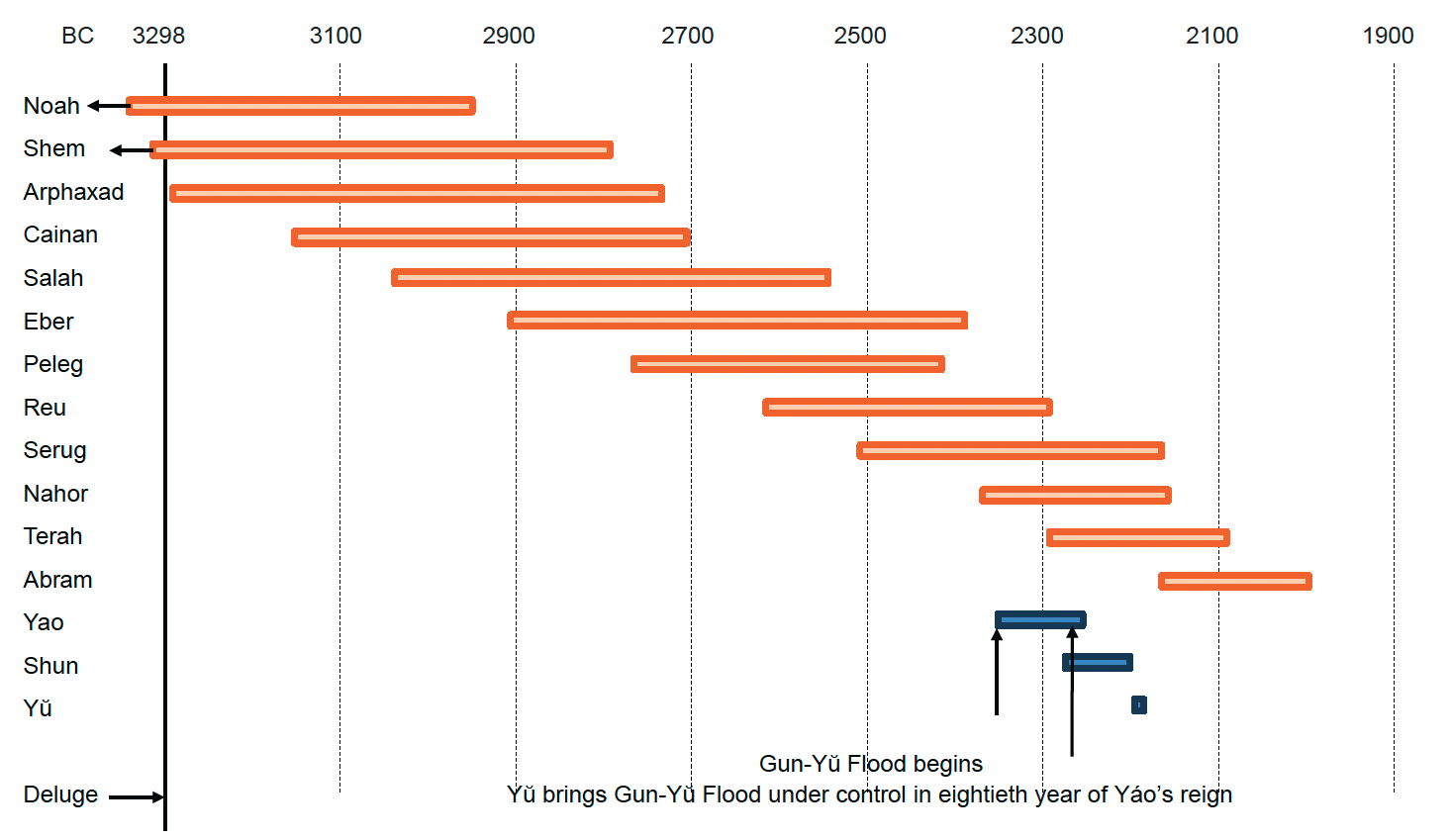

Fig. 5 shows that when the emperors are placed on the LXX timeline (fig. 5 uses Legge’s calculations; the differences are imperceptible at this scale), they rest comfortably, placing Yáo as a contemporary of Nahor and Terah, nine and ten generations after Noah, respectively (counting Cainan). Under this timeline, Yáo’s rule would start in 2357 B.C. per Legge (Waltham 1971), only 71 years after the death of Peleg in 2428 B.C. However, his reign would start 410 years after Peleg’s birth in 2767 B.C., arguing for the Dispersion to come early enough in Peleg’s life for the Chinese and the Miao to have been in China.

Table 1. Patriarchs from Adam to Abraham.

| Masoretic | Septuagint | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patriarch | Life Span | Born | Died | Paternity | Life Span | Born | Died | Paternity |

| Adam | 930 | 4004 | 3074 | 130 | 930 | 5554 | 4624 | 230 |

| Seth | 912 | 3874 | 2962 | 105 | 912 | 5324 | 4412 | 205 |

| Enosh | 905 | 3769 | 2864 | 90 | 905 | 5119 | 4214 | 190 |

| Kenan | 910 | 3679 | 2769 | 70 | 910 | 4929 | 4019 | 170 |

| Mahalelel | 895 | 3619 | 2724 | 65 | 895 | 4759 | 3864 | 165 |

| Jared | 962 | 3544 | 2583 | 162 | 962 | 4594 | 3632 | 162 |

| Enoch | 365 | 3382 | 3017 | 65 | 365 | 4432 | 4067 | 165 |

| Methusaleh | 969 | 3317 | 2348 | 187 | 969 | 4267 | 3298 | 187(1) |

| Lamach | 777 | 3130 | 2353 | 182 | 777 | 4080 | 3303 | 182 |

| Noah | 950 | 2948 | 1997 | 502 | 950 | 3898 | 2948 | 502 |

| Shem | 600 | 2446 | 1945 | 100 | 600 | 3396 | 2796 | 100 |

| Flood | 2348 | 3298 | ||||||

| Arphaxad | 438 | 2346 | 1908 | 35 | 565 | 3296 | 2731 | 135 |

| Kainan (2) | 460 | 3161 | 2701 | 130 | ||||

| Salah | 433 | 2311 | 1878 | 30 | 460 | 3031 | 2571 | 130 |

| Eber | 464 | 2281 | 1817 | 34 | 504 | 2901 | 2397 | 134 |

| Peleg | 239 | 2247 | 2008 | 30 | 339 | 2767 | 2428 | 130 |

| Reu | 239 | 2217 | 1978 | 32 | 339 | 2637 | 2298 | 132 |

| Serug | 230 | 2185 | 1955 | 30 | 330 | 2505 | 2175 | 130 |

| Nahor | 148 | 2155 | 2007 | 29 | 208 | 2375 | 2167 | 79 |

| Terah | 205 | 2126 | 1921 | 70(3) | 205 | 2296 | 2091 | 130 |

| Abraham | 175 | 2056 | 1991 | 100 | 187 | 2166 | 1991 | 100 |

(1) The LXX actually states 167, which many assume to be a scribal error. 187 agrees with the MT and makes Methuselah pass in the year of the flood.

(2) Found in the LXX, Luke 3:36, and Jubilees. Some assert this entry to be a scribal error.

(3) Smith suggest changes to this number (+60 years) that would align the birth of Abram more closely with Ussher and Jones.

Fig. 2. Timeline of the post-Flood patriarchs based on the Masoretic Text.

Fig. 3. Timeline of the post-Flood patriarchs based on the Septuagint.

Fig. 4. Post-Flood patriarchs from Masoretic Text plus reigns of Yao, Shun, and Yŭ based on Griffith and White (blue); and Yáo and Shun based on Wu Qinglong (red).

Fig. 5. Post-Flood patriarchs from Septuagint plus reigns of Yao, Shun, and Yŭ based on Legge.

A Hypothesis

A proposed hypothesis is that Yáo was not Noah but was someone who was descended from Noah after approximately 12 generations. The Miao oral tradition lends extremely strong support to this by documenting the lineage of the Miao people and connecting them to the Chinese eight generations after Noah and four generations before Yáo. Yáo no doubt ruled in China and encountered regional flooding. This hypothesis requires either Griffith and White, Liu Xin, or Legge to be wrong about some date(s), like the date of the Deluge, or the regnal dates of Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ. Taking the traditional dates for Yáo at face value would push the Deluge farther back in history than the MT would allow, but it would rest comfortably on the LXX timeline.

One implication of this hypothesis is that Yáo was slightly ahead of being contemporaneous with the founding of Babylon (B#2; see above) c. 2234/3 B.C. but came on the scene some amount of time after the Dispersion. Based on these data, the identification of 2348/7 for the time of the Deluge, 2234/3 for the founding of Babel, and 2191 for the Dispersion are incongruent. A suggestion is that the first date identifies a watery event, including the Gun-Yǔ Flood and maybe Ogyges Flood, not fully explained by existing data, but too late and underpowered to be the Deluge. The second date seems to be a very solid estimate for the founding of Babylon c. 2234/3 B.C. without testifying in any way to the founding of Babel. Being associated with so many durations makes the date of 2191 B.C. significant in some way. More analysis is needed.

Conclusion

Griffith and White may have let ancient texts lead them in questionable directions. We are not sure that their durations are sufficient to establish all of the discrete events they claim to have shown, such as two divisions and two dispersions. The division plan they propose seems overly specific in claiming that the Peruvians were allotted a specific parcel of land when knowledge of the existence of the New World most likely had not been imparted by God. They also posit some events that are clearly impractical, such as the settling of Peru, Ireland, and Germany when there might not have been paths to those places. The settlements of Peru and China are implied to happen in the same year that their founders left western Asia, which is rapid travel indeed for migrating families.

If the endpoints of timelines do not identify the time and place for an event of interest but actually identify something else, we could be misled. We must not be influenced by our presuppositions. Griffith and White may have little basis, just as an example, for placing the founding of Babel at any specific point in history, and a similar issue seems to have led them to infer that a famous ancient Chinese emperor was the same person as Noah, which seems demonstrably false considering a host of reasons. These same data that refute the Yáo/Noah conflation intimate that something dramatic involving water must have happened to the world in the time frame of 2348/7 B.C., just not the Deluge.

References

Africanus, Scipio (f. 236–183 B.C.). 2019. Chronography, quoted in Eusebius of Caesaria (fl. A.D. 260/265–339/340), Praeparatio Evangelica (The Preparation for the Gospel) 10.10. Edited by Paul A. Boer, Sr. Translated by George Lewis. Independently published.

Answers in Genesis. 2016. “China: Kids Answers.” May 2. https://answersingenesis.org/kids/noahs-ark/flood-legends/china/.

Archer, Gleason L., and Gregory Chirichigno. 2005. Old Testament Quotations in the New Testament: A Complete Survey. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock.

Archi, Alfonso. 2015. Ebla and Its Archives, Texts, History, and Society. Studies in Near Eastern Records, 25–31. Boston, Massachusetts: De Gruyter.

Austin, Steve, Edmond W. Holroyd, and David R. McQueen. 2020. “Remembering Spillover Erosion of Grand Canyon.” Answers Research Journal 13 (September 9): 153–188. https://answersresearchjournal.org/remembering-erosion-grand-canyon/.

Bailly, Jean-Sylvain. 1779. Lettres sur l’Atlantide de Platon et sur l’ancienne histoire de l’Asie. Paris, France: Chez les freres Debure, Quai des Augustins.

Barnard, Noel. 1993. “Astronomical Data from Ancient Chinese Records: The Requirements of Historical Research Methodology.” East Asian History 6 (December): 47–74.

Baumgardner, John R. 1994. “Runaway Subduction as the Driving Mechanism for the Genesis Flood.” In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Creationism. Edited by R. E. Walsh, 63–76. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship.

Becerra-Valdivia, Lorena, and Thomas Higham. 2020. “The Timing and Effect of the Earliest Human Arrivals in North America.” Nature 584, no. 7819 (22 July): 93–97.

Birrell, Anne. 1999. Chinese Mythology: An Introduction. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Book of Jubilees. n.d. http://www.yahwehswordarchives.org/book_of_jubilees/book_of_jubilees_chapter_08.htm.

Braje, Todd J., Jon M. Erlandson, Torben C. Rick, Loren Davis, Tom Dillehay, Daryl W. Fedje, Duane Froese, et al. 2020. “Fladmark + 40: What Have We Learned about a Potential Pacific Coast Peopling of the Americas?” American Antiquity 85, no. 1 (January): 1–21.

Brasseaux, Shawn. 2021. “Is ‘Cainan’ in Luke 3:36 a ‘Scribal Error’?” For what Saith the Scriptures.org, May 10. https://forwhatsaiththescriptures.org/2021/05/10/cainan-luke-3-36-scribal-error/.

Bretz, J. Harlen. 1923. “The Channeled Scablands of the Columbia Plateau.” Journal of Geology 31, no. 8 (November–December): 617–649.

Cai, Xiaoyun, Zhendong Qin, Bo Wen, Shuhua Xu, Yi Wang, Yan Lu, Lanhai Wei, Chuanchao Wang, Shilin Li, Xingqiu Huang, Li Jin, Hui Li, and the Genographic Consortium. 2011. “Human Migration Through Bottlenecks From Southeast Asia into East Asia During Last Glacial Maximum Revealed by Y Chromosomes.” PLOS ONE 6, no. 8 (August 31). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024282.

Christie, Anthony. 1968. Chinese Mythology. London, United Kingdom: Hamlyn.