The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

As a result of archaeological research, the landing of the sons of Noah and their early movements are able to be followed. It will be argued that the biblical history alone makes sense of the findings and that the long ages usually espoused have no validity. Careful attention will be given to the early technology Noah’s sons used for survival and the routes they took to the Mesopotamian plain. General principles will be discussed first. Next, the sons of Shem will be traced to their settlements. Later discussions in separate articles will trace the sons of Ham and Japheth. Revised dates given in this article are the author’s own revised dates from the Scriptures and archaeological correlations.

Introduction

Biblical history allows only a few generations for the migration of people across the world. Secular historians, however, argue for long periods of time in many areas, including the Middle East. The theory that there is a “Chest of Drawers” pattern (long period following long period) has been heavily adhered to, and it still exercises a powerful hold on archaeologists.

The significant event that philosophically separates the two views, and also liberal and short-age biblical students, is the great Flood. The acceptance and understanding of the nature of Noah’s Flood is seminal to understanding the ancient historical account. While it is not the core subject here, there already being a plethora of good creationist scientific literature (and increasing daily) on the nature of the Flood, it will be instructive to cite several basic principles which creationists believe identify the nature of that event and help to explain the spread of the post-Flood population.

- The Flood was a global tectonic, catastrophic event, precipitated by sub-oceanic volcanism and plate movement: “All the fountains of the great deep [were] broken up” (Genesis 7:11, KJV).

- It produced increasing catastrophic tsunamis, moving and then depositing massive sedimentary layers across the planet, both at the build-up and also the wind-down of the flood waters: “And retreated the waters from the earth, going and retreating” (Green 1976, 18; on Genesis 8:13). Massive amounts of dead creatures were buried quickly in this process, providing suitable conditions for fossilization.

- The hot, sub-oceanic eruptions multiplied the precipitation to give the unusual quantity of rain inferred by the Flood account.

- Following the massive movements of the continental plates under the Flood waters, a repositioning of the continents occurred (further post-Flood adjustments continued as the movements settled down to present-day rates).

- Some young-earth creationists have concluded that the pre-Flood earth was initially one giant continent and that the hills and mountains on that continent were not of the scale of the present world. The former belief is, in part, deduced from Genesis 1:9: “The waters gathered to one place” (emphasis added). If the waters gathered to one place, then it is inferred that the land must also have been in one place.

- As a result of the powerful geological and hydrological forces of the Flood, the continents were displaced across the planet to their present positions. In the process, mountain ranges were forced up to their present levels, making it impossible for such a Flood event of this type to occur again (Psalm 104:8–9). The biblical descriptor of Noah’s Flood is a Hebrew word used only for that event and not about other types of floods.

- A post-Flood Ice Age followed, precipitated by the unique conditions and changes created by the Flood event. This produced a drop in sea levels of the order of 300 ft, creating many temporary land bridges which were used for migration. Later, as the ice melted, sea levels rose to just above present levels, followed by a slow settling.

The Flood of Noah was not just a heavy rainstorm, nor should it be confused with the post-Flood rise of the oceans at the ice-melt or the flooding of coastal areas, which is well-recognized and seen by Woolley’s finding of flood layers at Ur, which indicate an oceanic rising flood (Oppenheimer 1998, 49–62).

The Dispersion

The Bible indicates profoundly and unambiguously that all the present world’s population are descendants of the three sons of Noah (Genesis 10:32): Shem, Ham, and Japheth are the origin of all the families of the earth. Genesis 10, moreover, gives a detailed family basis for that origin, listing somewhere around 65 original family groups at the moment of dispersion (some variation is possible, depending on which groups one holds to be the significant ones). These family groups all came from the sons of Noah and spread out over the entire earth after the dispersion from Babel.

Genesis 11 gives a narrative of the migrations from the Ark to other areas of the Middle East. It also gives generational times for that period—approximately 30 years per generation. Genesis 10:25 indicates that the dispersion from Babel occurred in the fourth generation, suggesting that Babel occurred somewhere close to 100 years after the Flood. I am here using the figures of the Masoretic text of the Bible. Many Christian researchers, especially those who still hold to the main thrust of the secular chronology of the ancient world which is based upon Egypt as their gold standard, are tempted to use the chronologies given in the Septuagint or Samaritan texts, both of which have a longer time span. However, I believe that this is because they are hamstrung by the accepted secular chronology, with its elasticized timescales and the assumption that its interpreted time periods are correct and set “in cement”—a conclusion with which I seriously disagree.

There are multiple conspiratorial claims made by some about both the Masoretic and the Septuagint texts and their chronologies/genealogies. This author rejects claims that there were significant, deliberate tampering with these texts (the reason for their differences still only being theories). While admitting some variations, I am yet to be convinced that the Masoretic genealogies/chronologies should be dismissed in favor of the Septuagint (for example, the Septuagint’s genealogies would have Babel occurring at least 533 years after the Flood, allowing literally millions of people to be born by that time, which would diminish the significance of the Babel dispersion). I believe the rush to the use of the extended Septuagint chronology (of which there are three versions), is mostly based on the willingness of the proponents to rely uncritically on the accepted extended chronology of the ancient world. This chronology rests partly upon the unproven interpretation by modern scholars of Manetho’s histories. Although many proponents of the standard chronology would not accept this claim, on discussion, it is clear that many of them are significantly, and, often unconsciously, strongly influenced by that paradigm. The assumption is that those histories demand an overall sequential chronology. Contrariwise, aspects of Manetho’s histories, in fact, allow much possibility of frequent contemporaneity and parallelisms, with different concurrent dynasties often having a different geographic basis (Osgood 2020, 247–250).

The Time of Babel

Later, I will discuss a possible site of Babel (although, I personally believe that no ultimate conclusion of its site is likely to be secured) and the significant people involved, but let us first look at the likely population. When thinking of the Tower of Babel, many have the idea of a close group of people surrounding the area, most likely in lower Mesopotamia. But the reality appears to be that while a significant number of families were in that region, others were quite further afield. Not only have people who can be traced back to that time been located who are still in the mountains, but others were in the northern areas of Mesopotamia at the time when Babel’s dispersion can be pinpointed (see later). It also appears that there were some individuals who had, in fact, begun to migrate outwards in several directions, people, who in the archaeological record, the long-age proponents call Paleolithic, Epipaleolithic, and Pre-Pottery cultures. This pre-Babel migration does not contradict the biblical record, but perhaps it puts a motive on the reason why the people were wanting to build a central shrine—to stop people from being “scattered abroad.” This was a reality that was beginning to manifest itself, apparently causing concern to some. For, as the ongoing discussion will show, there is definitely evidence that fits this idea.

How Many People?

I have previously calculated in Over the Face of All the Earth that the possible population by the time of Babel (using Masoretic text figures) was close to 8,000 people, allowing family units at the dispersion of around 130 individuals on average (Osgood 2015, 37–40). This, however, may well be a conservative figure. An Armenian legend relates that one of their progenitors “revolted against the ‘titan Bel’ after the destruction of the tower of Babel; taking with him his entire family numbering some three hundred persons, and also other men, and went to the land of Ararat” (Der Nersessian 1969, 21).

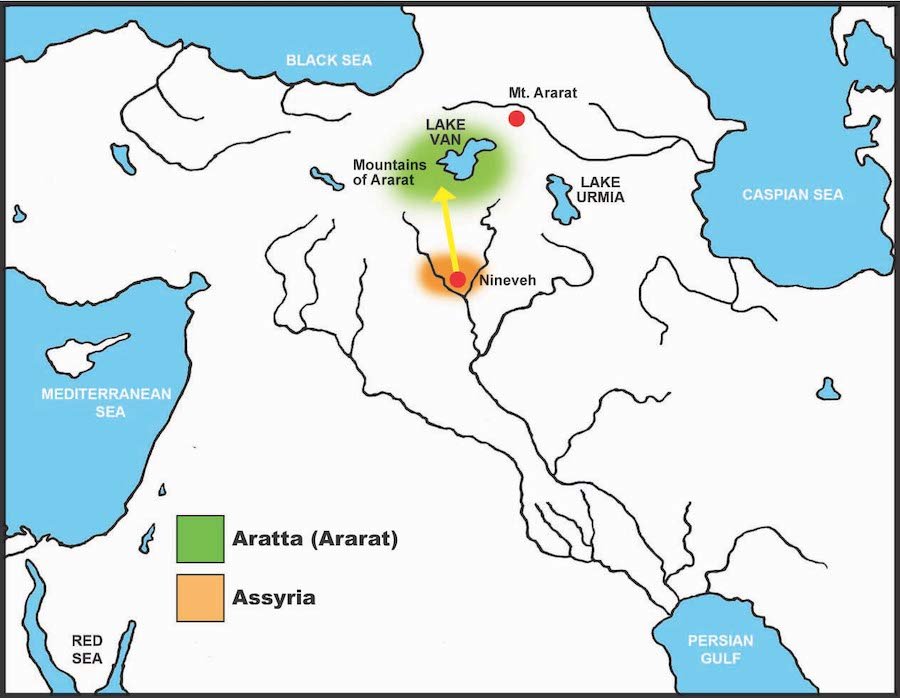

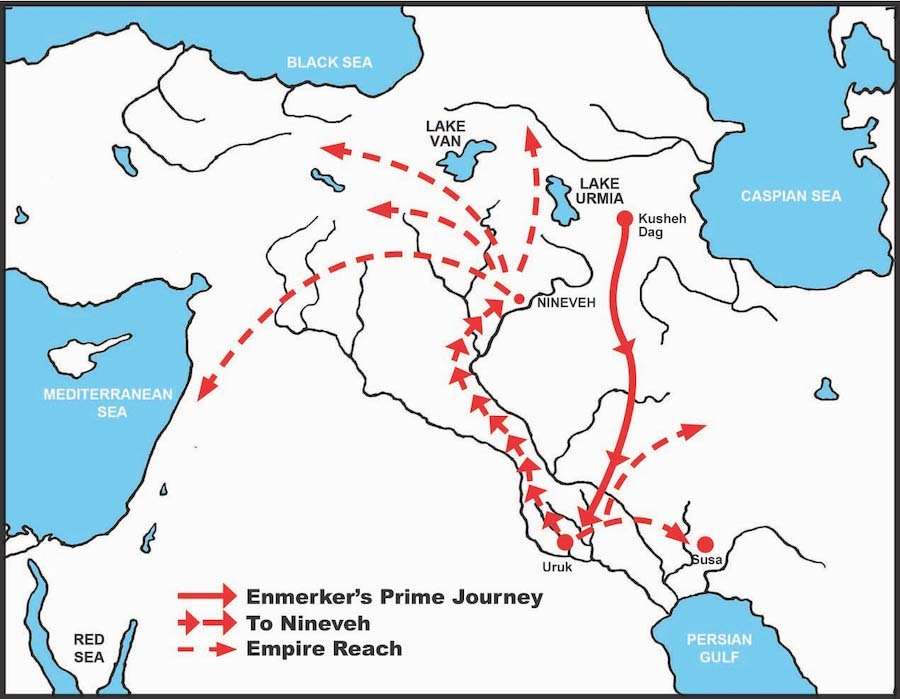

The legend then tells of a great battle that occurred in which Bel was killed by an arrow through the chest near a salt lake which is believed to be Lake Van. The legend has some geographical significance because Nimrod, who is clearly the Bel of the story, was then in Assyria after building Nineveh, which is, of course, just south of that region. And legends from Nimrod himself (Sumerian Enmerkar) tell of ongoing conflict with Aratta (including a year-long siege), which can cogently be argued is, in fact, the Ararat region (Urartu) (Kramer 1963, 42; Rohl 1998, 136–139).

There is today, on the west of Lake Van, a mountain called Nemrut Dag (the Mountain of Nimrod), with a small lake Nemrut Golu (the Lake of Nimrod) (fig. 1). Today, the significance of such names is hard to ascertain, but the names do seem to fit with the legend.

Fig. 1. The battle against ‘Aratta.’

One of the stumbling blocks to an adequate historical picture is the inaccurate classifications and misunderstandings of ‘periodization’ held by several archaeologists. Periodization is “a form of historiological cognition proposed by the human mind for making the past intelligible and meaningful by dividing the collective past into compartments along time” (Sato 2001, 15,686). However, much evidence is accruing that suggests that many of these ‘periods,’ in fact, represent contemporary cultures, and some of their interactions have been mistaken for period terminations, when, in fact, contemporaneity continues.

We will now follow and trace the biblical and archaeological picture from the time of the landing of the Ark. I wish to emphasize that this part is concentrating on the sons of Shem, and only such others that elucidate that history.

Down from the Mountains

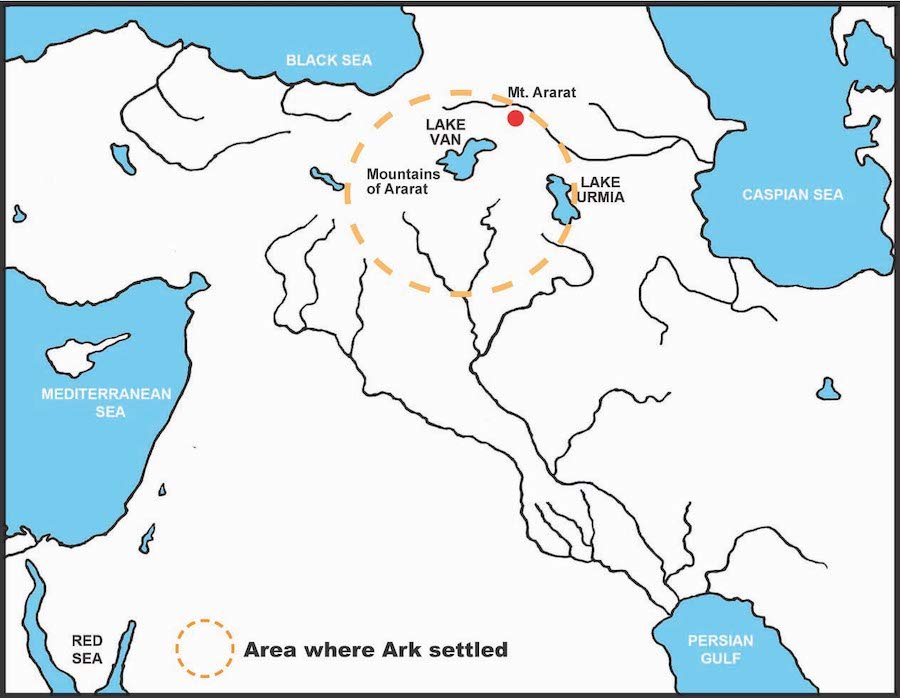

Embarking from the Ark into the area encompassed by the mountains of Ararat at either side of the Araxes River, and close to the area south of the Caucasus with the Kura River, the survivors could have gone a number of directions. The most likely first course of action would have been settling, however temporarily, in the immediate area described as “the mountains of Ararat” (Genesis 8:4). Tools may have been available on board the Ark, but certainly the likelihood is that they used the artifacts at hand. Stone technology would have been needed, especially as the people multiplied. Let me here dispel one myth—these people were sophisticated people from before the Flood, and it can surely be assumed that they had the ability to quickly put stone technology to work, even if they were “a little rusty” in technique at first (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Area where the Ark settled.

The easiest and quickest technology in stone is what is referred to as Acheulian, which ranges from simple pebble tools to worked hand axes. These tools are found around the mountains of Ararat, and they are often found around the earliest sites in many places around the world. These are simple, quickly-made tools suitable for survival. They are also the earliest tools found in a very wide arc geographically due to the fact that this technology is quick to make and would be appropriate for use in areas immediately after settling until time and conditions allowed improvement in technique. Therefore, these tools cannot be used for absolute dating but can only show the relative progression of technology within each civilization. With time and the onset of colder temperatures, we find within this same area some of the technology used by people who needed to hunt larger, cold-climate animals, the Mousterian-type technologies with the so-called Levallois point.

The Acheulian and Mousterian techniques have been found in both the mountainous areas and areas around the river valleys, and evidence is accruing that such techniques also had a wide distribution from Europe and Africa to China. However, no long periods of time or primitive-to-sophisticated development is here needed, simply the need to create. These technologies were used and transported widely across the earth as people migrated. In the mountainous regions in which the Ark landed, both these technologies have been found, fitting the conventional ‘Early’ and ‘Middle Paleolithic’ requirements, but in no way justifying the vast long-age concept which has spawned those terms.

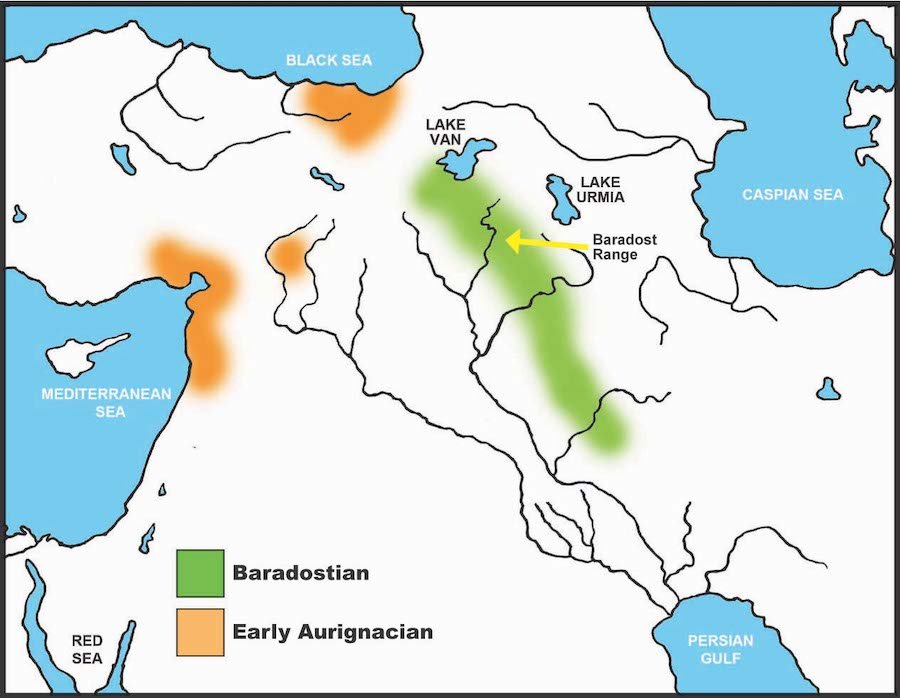

Later, two further developments of tools are evident, which were required by changing conditions and made possible by the availability of time to create the tools to fit that need (these fitting the long-age ‘Upper Paleolithic’ label). First, there is the Baradostian cultural technology in the Middle East (seven known sites) along a relatively small range in the northern Zagros Mountains, along with its more westerly associate the Aurignacian (Delson et al. 2004, s.v. “Upper Paleolithic”) (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The locations of the Baradostian and Early Aurignacian technologies.

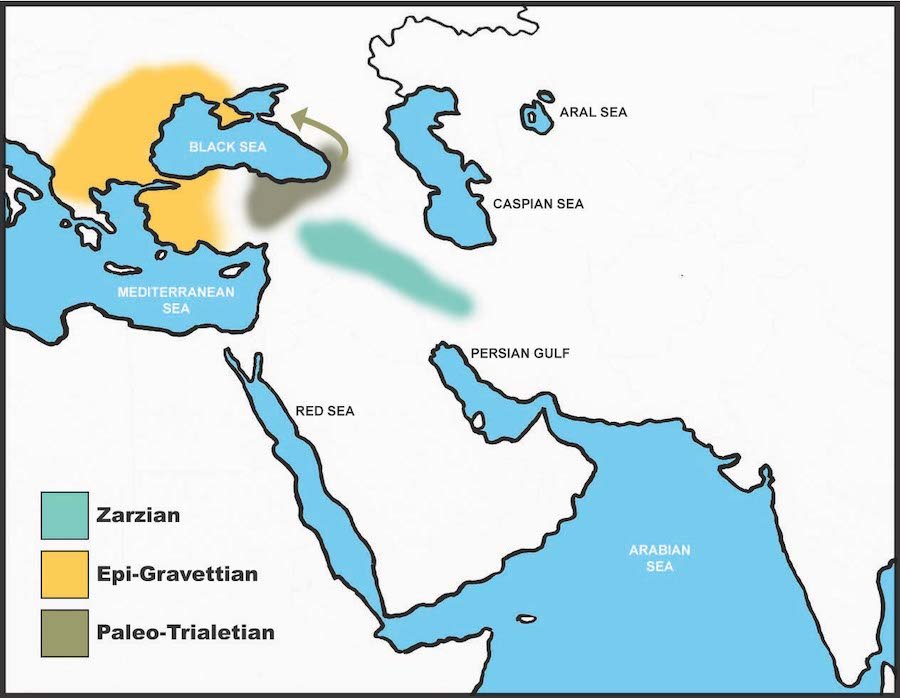

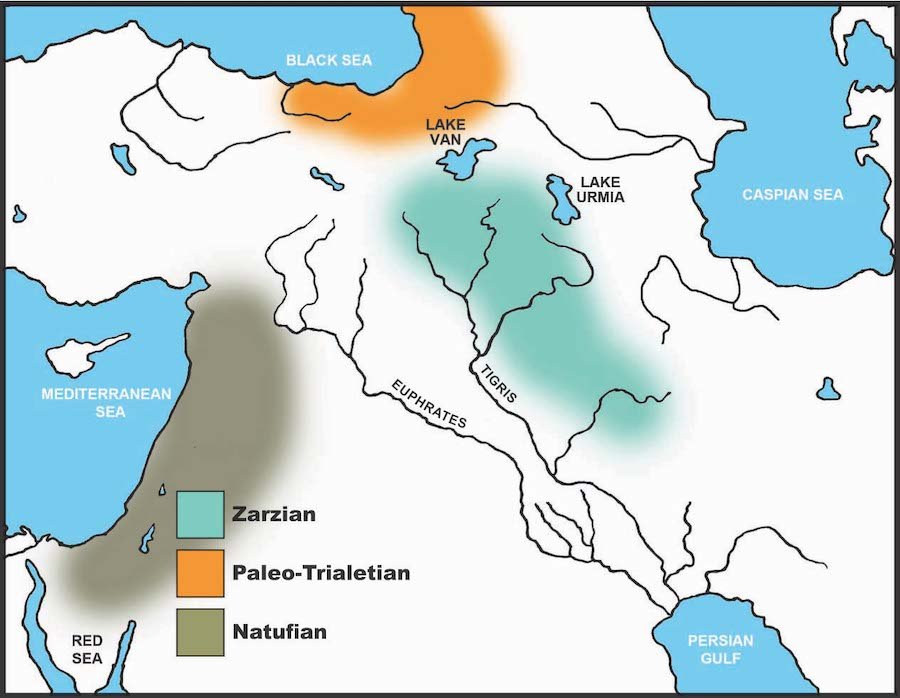

Second, there is the more voluminous and widespread Zarzian technology (20 known sites so far), with its more westerly Gravettian, Epi-Gravettian, and Paleo-Trialetian contemporary ‘cultures’ (figs. 4 and 5). These technologies are contemporary with a different technology known as Natufian further south. All these variations cry out for possible identification with individual family associations; such thinking, however, is discouraged and even actively rejected by evolutionary proponents.

Fig. 4. The locations of the Zarzian, Epi-Gravettian and Paleo-Trialetian technologies.

Fig. 5. The locations of the Zarzian, Paleo-Trialetian and Natufian technologies.

The discussion of these stone technologies in the “scientific” literature is heavily based on the assumption of very long ages. Long-age theories lose their impact, however, if these cultures are, as the Bible would suggest, close together in time. Different families, different climatic conditions, different animals to hunt, and different cultural traits—these factors do not feature heavily in the discussion. Rather, it is assumed that these people are “primitive” and are yet to learn these technologies, which are assumed to be acquired over thousands of years.

The Baradostian and its southern variation Rostamian, while showing cultural similarities, are almost certainly a product of different families than those who produced the Aurignacian. Furthermore, as shall be demonstrated, the Baradostian is likely to be associated with Shemitic and possibly Hamitic families; whereas (as I will discuss in another article) the Aurignacian has a clear, mostly Japhetic label on it. But the very fact that these are seen to belong to the one continuum suggests that these people are related early on in culture and possibly genetically, as were the sons of Noah. Yet we are not dealing with one culture but multiple related cultural variants: “[The] UP [Upper Paleolithic] record of the Zagros mountain range reflects multiple technological traditions instead of a single one” (Ghasidian, Bretzke, and Conard 2017, 33). In any case, these artifacts give witness to the early days of the sons of Noah in the mountainous areas, as would be expected, and the beginning of a radiation out from there, rather than an origin in Africa as presently held.

The Zarzian is more widespread through the Zagros region. More sites have been found, but this would be expected in a multiplying population. Many believe that the Zarzian grew out of the Baradostian, and this is likely, but perhaps there are also other localized cultures that progressed that way in the same area which had an influence. We are dealing, after all, with different people with separate talents; a fact, which, I feel, is easy to overlook as one seeks to systematize artifactual finds. Individuality will always be present. The Paleo-Trialetian is potentially more closely related to the Zarzian.

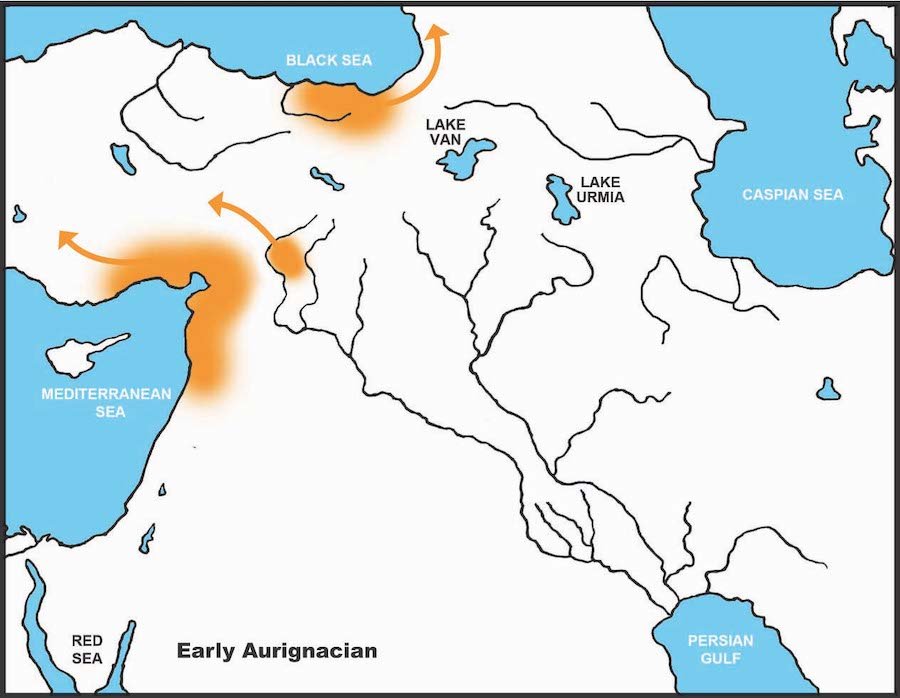

The Gravettian and Epi-Gravettian, per se, are really not highly relevant to the Zagros area. They appear to begin their expression in the North Pontic region, passing mostly west and north. However, the Early Aurignacian, in particular the Early Near Eastern Aurignacian, is found around the upper Euphrates and its headwaters, the eastern and south-eastern shore of the Black Sea, and down as far as North Syria/Cilicia before its soon expansion, mostly into Europe (fig. 6). As such, it reflects the early position of some of the sons of Japheth, particularly, but not exclusively, Javan and Gomer. This will feature in a later paper.

Fig. 6. The location of the early Aurignacian technology.

Cultures dating to soon after these ‘Upper Paleolithic’ industries in both the Levant and the Zagros Mountains, which are important staging areas for migration globally, still show connections with those older industries: “The Epipaleolithic cultures of the Levant and Zagros obviously share many traits, and both may be viewed not only as the final carriers of a long-lived Paleolithic tradition but as cultural innovators as well” (Solecki and Solecki 1983, 132). But, they would hardly be “innovators” if it had taken tens of thousands of years for such innovation! The theory of long ages falls woefully short. And the traits are there almost certainly because of the overlap of the lifetimes of many of these people. In fact, in the Middle East, I would argue that close, cultural-connecting threads over time are more common than not. Development, or changing cultures within the same area, can be illustrated by the Zagros rock shelter of Warwasi and the cave of Ghar-i Khar northeast of Kermanshah. Warwasi contains Mousterian, then Baradostian, and then Zarzian occupations; while, Ghar-i Khar has middle to upper ‘Paleolithic’ occupations, “one of which has tentative cultural and temporal correlations with some phase of the Zarzian, a continuation of earlier traditions” (Solecki and Solecki 1983, 127–128).

Bible-Related Placement

Abraham was born close to 1950 B.C., 350 years after the Flood (Masoretic text). I have elsewhere argued that his early days should be seen against the Early Dynastic II (ED II) of Mesopotamia (Osgood 2020, 115–134). If then an argument can be made that reaching the Sumerian Plain would be logically circa. Fifty years after the landing of the Ark, we then have another 300 years to cover all ‘periods’ until the beginning of ED II. This figure is not fanciful, nor are the many building levels against such a conclusion, for we are here witnessing significantly rapid changes in climate, including a very strong Pluvial Period. And at the Pleistocene/Holocene junction, a rapid rise of the sea level due to rapid ice melt flooded the Persian Gulf to 5 m above present levels, bringing Ur and Eridu to seafront. Wooley at Ur discovered this “flood,” which was a sea-rise oceanic flood (Oppenheimer 1998) known as ‘the Holocene Transgression,’ not the earlier cataclysmic Flood of Noah which is witnessed by the sedimentary geological column.

Population 350 years after the Flood could be massive. Theoretically, if we do not count conflict, disease, and infant mortality, a figure of 3.5 million could be present if we use the number of males in the first and second generations mentioned in Genesis 10 and assume an average male reproduction rate of 3/generation and a generation time of 30 years (Genesis 11). The population would be 88 million if 4/family, and 634 million if 5/family. I have approximated the count of first- and second-generation post-Flood male groups in Genesis 10 to be 65. Of course, this is only counting males; we double that for the total population. The actual figure will not be perfectly known, but I have put these numbers forward to give a sense of population multiplication—which is very rarely appreciated until one does the math.

Later, I will deal with the earliest Mesopotamian cultures, but in order to get there, I will name them and show the evidence of their routes to their destinations. I emphasize that the subject here is concentrated on the sons of Shem.

Earliest Sumerian Cultures

The earliest cultures on the Plains of lower Mesopotamia are usually classified as Chalcolithic. In the conventional chronology, they are grouped by period-following-period over a length of 2,000 years (5000 B.C.–3000 B.C.) and previously were seen, as Joan Oates (1983, 254) has described, as a “chest of drawers sequence.” This concept has recently taken a battering, and it will soon be mentioned why.

Such demands contemporaneity of at least some of these cultures, as Joan Oates herself admits, and in a further paper I will point out that this contemporaneity extends also to the Neolithic and Chalcolithic of other areas, contrary to the presently accepted theory. In particular, it can be also extended to the Neolithic and Chalcolithic in some areas where the Chalcolithic of Jordan is now believed to overlap both Neolithic and Early Bronze Ages (North 1982, 66). There is no absolute principle demanding each age follows rigidly after another in sequence: after all, we are here dealing not with time necessarily but with technology. In a following article, I will, in fact, show that Pottery Neolithic A and B of Palestine (which are not relevant to Shem) were contemporary with Early Chalcolithic of Mesopotamia.

Sumer

David Rohl (1998, 134–135), following on the work and suggestions of Poebel (1931) and Kramer (1963), has indicated that the name Sumer (biblical Shinar) is derived from the name of the father of its first inhabitants—Shem, the second son of Noah. Shem (Semitic) is from Shemer-Shumer (Sumerian); the unpronounced ‘r’ is dropped in the Semitic. Shemer-Shumer is known to us as Sumer. The Egyptian name was Senaar and was placed in the Bible as Shinar by the Egyptian-trained Moses—a rebuke to the fallacious claims against Mosaic authorship of Genesis. The Egyptians placed Senaar (Sumer) in southern Mesopotamia, from whence they received an influx of people by sea during their Gerzean Period (Late Uruk/Susa of Mesopotamia), which will be discussed later. Attempts to place Sumer further north fail to appreciate the archaeological history of Sumer, which was unknown to archaeologists until the earth of Southern Iraq during the nineteenth century revealed this previously unknown civilization (to the archaeologist).

At the time of Babel, which I will later attempt to pinpoint, a migratory radiation would occur outwards, like the ripples on a pond. Those traveling far would naturally fall back on whatever ‘basic’ technology is available in the surrounding environment, so that the more peripheral peoples would appear to the “long-agers” to be less developed. On the contrary, they are simply using basic technology to survive at the same time as those more centrally located use “advanced” technology. This is definitely obvious in some peripheral areas.

The Sons of Shem—Their Early Settlements (Elam, Ashur, Arphaxad, Lud, Aram—Genesis 10:22)

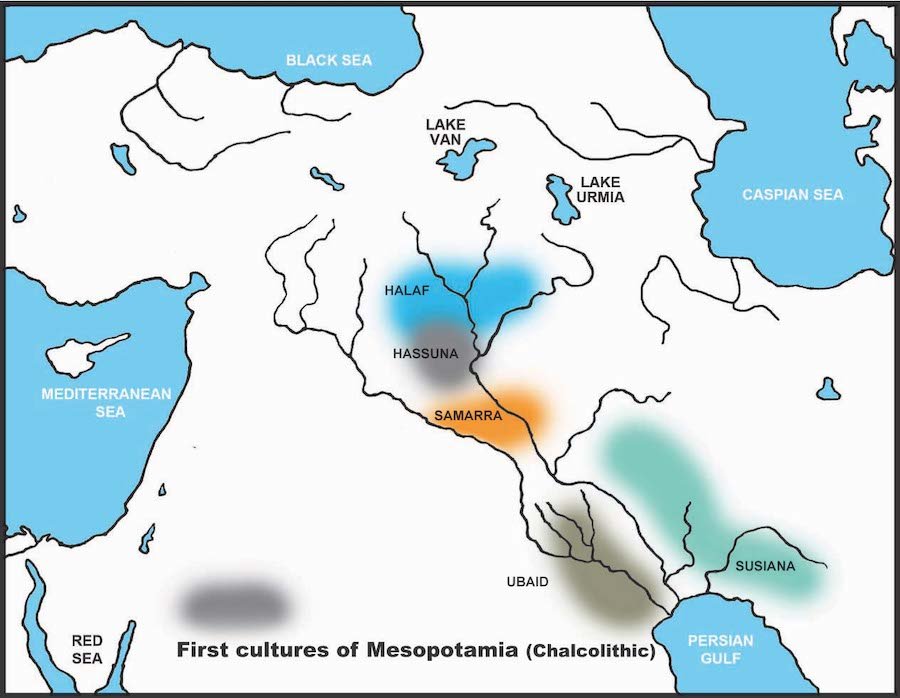

The earliest archaeologically-defined cultures of the Mesopotamian plain are the following: Ubaid, close to the Iranian Susiana; Samarra on the mid-Tigris; Hassuna, further north; then Halaf. It will be my contention that all of these cultures are initially Semitic (Shemitic), which gave rise to the Mesopotamian Plain being initially known as Shemer, Shumer, Sumer—”the land of Shem” (fig. 7).

Fig. 7. First cultures of Mesopotamia (Chalcolithic).

The Uruk culture is a later arrival and addition which I will identify as clearly Hamitic and an identifier leading to the beginning of the Babel dispersion. All of these cultures can be retrospectively traced back to the areas around the western area close to Lake Urmia by pottery culture and the above-mentioned stone cultures.

Evidence continues to reveal early agriculture. It is increasingly being accepted that aceramic (previously thought of as Pre-Neolithic) groups were often using early agriculture: “If so, it suggests that formally aceramic groups, with and without brick buildings, may already have been cultivating barley and emmer wheat” (Smith and Young 1983, 148). Such, of course, is consistent with the Bible narrative.

The Contemporaneity of These Cultures

The contemporaneity of some of the Early Chalcolithic cultures of the Mesopotamian Plain has become increasingly obvious, despite earlier hard-held beliefs. Oates (1983, 254) explains:

It is quite clear that in the Hamrin at this time there were potters working in both the Halaf and Ubaid traditions, perhaps even side by side in the same villages. Certainly, the contemporaneity of these two very distinctive ceramic styles cannot be in doubt. . . . In the Hamrin we have the first unequivocal evidence of such a situation in Near Eastern prehistory, where previously we had assumed a “chest-of-drawers” sequence of cultures.

Using Choga Mami as a specific example, she reveals how archaeology is constantly uncovering contemporaneity and interrelationships of past cultures:

The Mandali survey and subsequent season of excavation at Choga Mami (Oates 1966, 1968, 1969) extended the known range of Hajj Muhammad pottery some 150 km to the northeast of Ras al Amiya and provided the first evidence, albeit still ambiguous, of the relationship between Samarra and early Ubaid. (Oates 1983, 256)

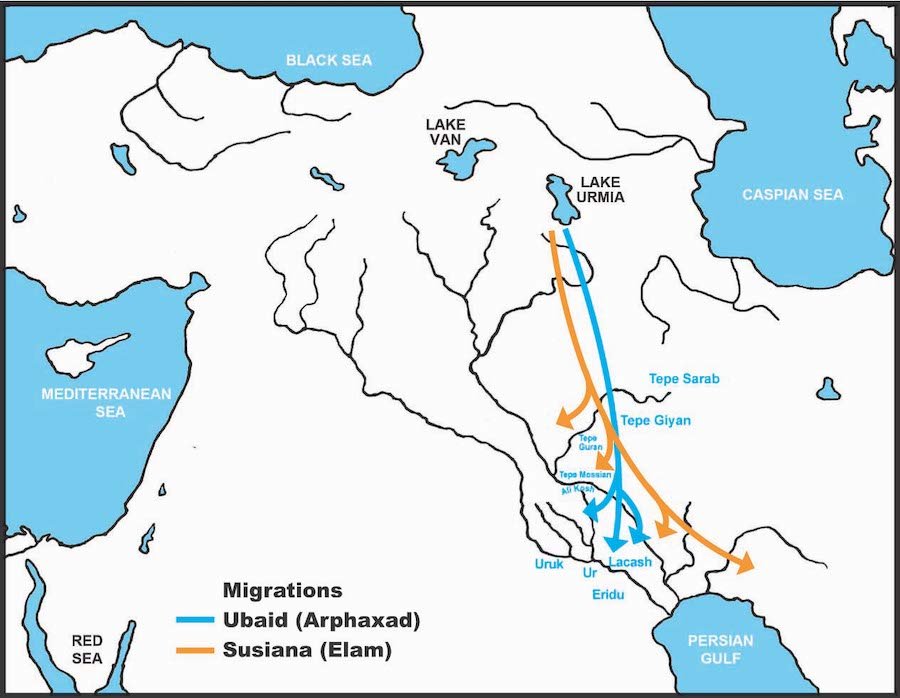

Tracing the Early Cultures to the Mesopotamian Plain

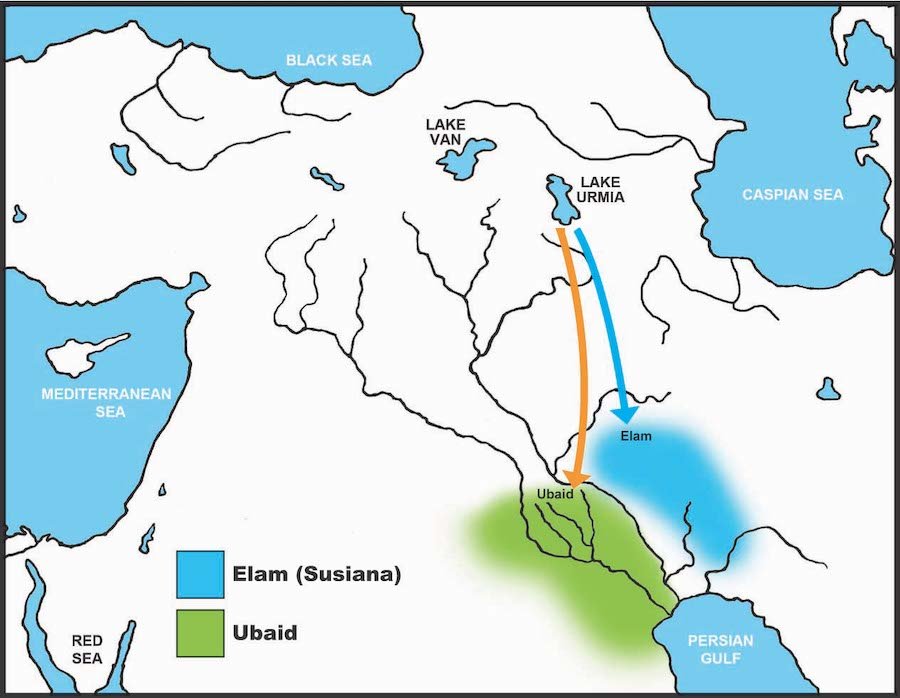

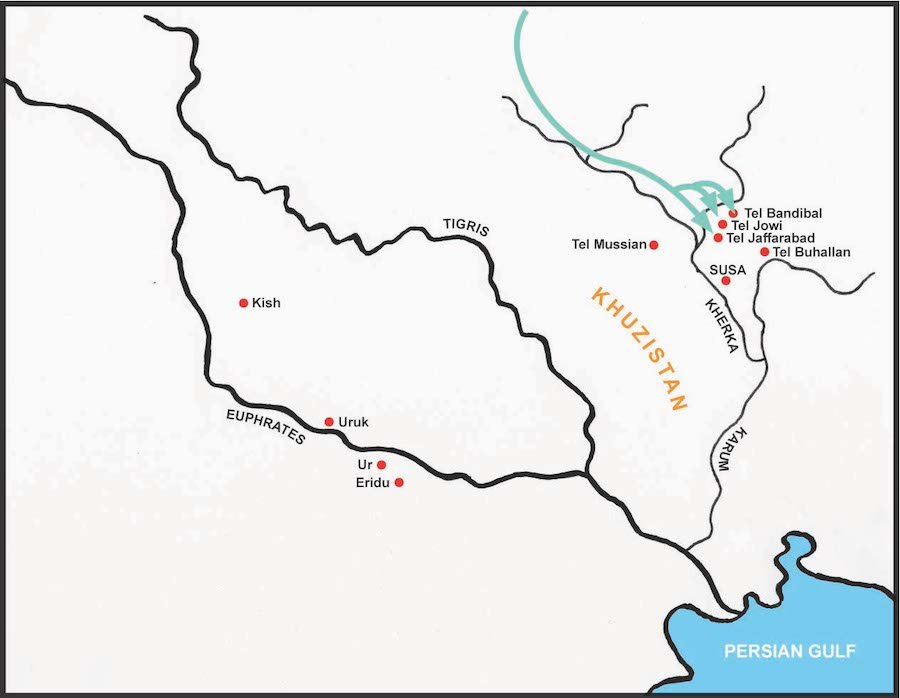

Let us then briefly follow each of these cultures to the Mesopotamian Plain (this will be expanded individually further on). Susiana and Ubaid will be considered first. These, against the biblical narrative, can be associated respectively with Shem’s sons Elam and Arphaxad (see later as we discuss them specifically). David Rohl (1998, 136–139) argues a route for the early cultures of the plain from the Lake Urmia region (citing Yanik Tepe as an example) via Tepe Guran to Susiana and the Ubaid areas. He also extends it via Jarmo to the northern sites. His route is almost certainly correct for Susiana and Ubaid. However, although a ‘relationship’ between the northern cultures (Halaf, Hassuna, and Samarra) and the culture at Jarmo also stands, the northern cultures, while clearly culturally related, used a different route to the plain. We follow them then from the Urmia region. Elam’s descendants can be related via Guran and appear early in Khuzistan (Susiana), but it is clear from later history that they spread and settled fairly widely from north of the Diyala River down as far as Susiana-Khuzistan. They, no doubt, followed the Kerkha River Valley to Susiana Khuzistan. The same route can be suggested for Arphaxad’s descendants via the Kerkha to Tell el-ˈOuelli, Eridu, Al Ubaid, and Ur on the alluvial plain (figs. 8 and 9).

Fig. 8. Early migrations of Elam and Ubaid.

Fig. 9. Migrations of Ubaid (Arphaxad) and Susiana (Elam).

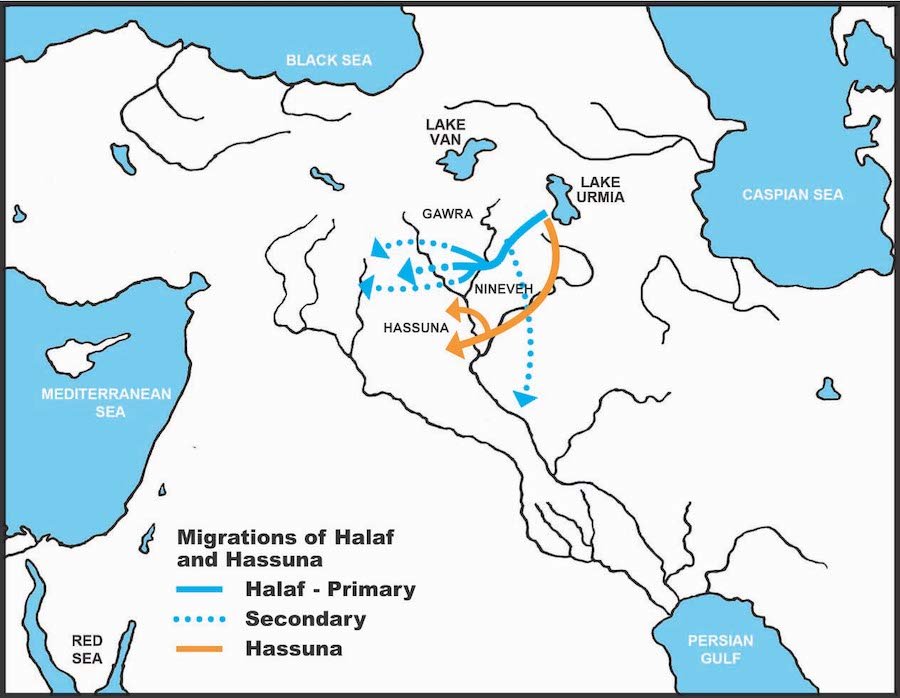

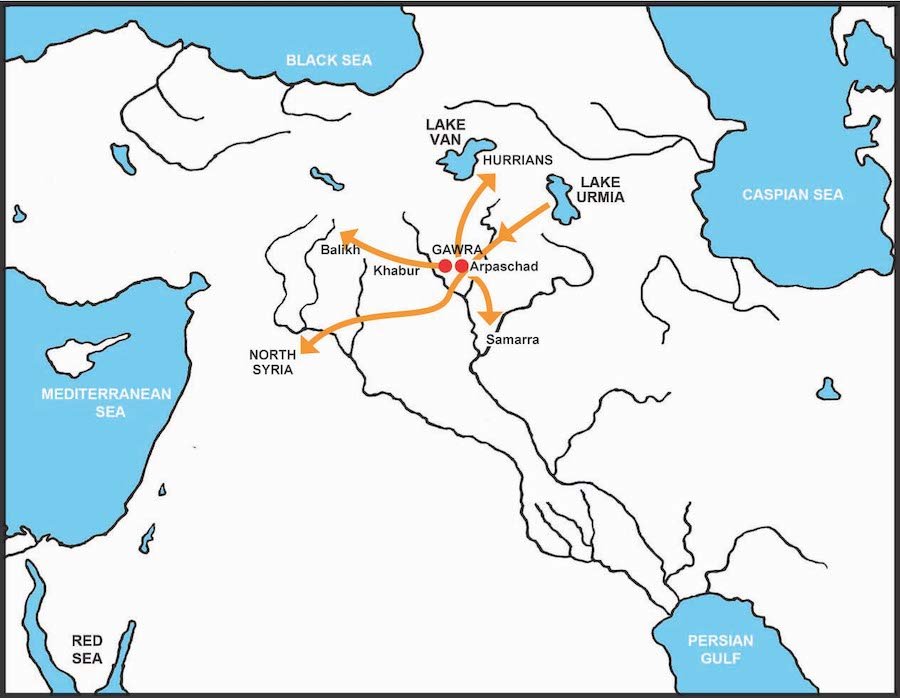

Halaf (Aram), however, can be followed via the Baradost range and Shanidar and Banahilk via the Greater Zab to settle first at Tepe Gawra and Arpachiyah. A secondary movement of Halaf to culturally-related Samarra is traced southward via Matarrah to the mid-Tigris area. Hassuna (Asshur) appears to have passed via the Lesser Zab and Jarmo to settle at Hassuna, Yarim Tepe, and Level 1 at Nineveh. The result was a nearly contemporary incipient settlement prior to the Babel event of early Halaf, Hassuna, Samarra, Ubaid 1 and 2, and Susiana A to C (fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Migrations of Half and Hassuna.

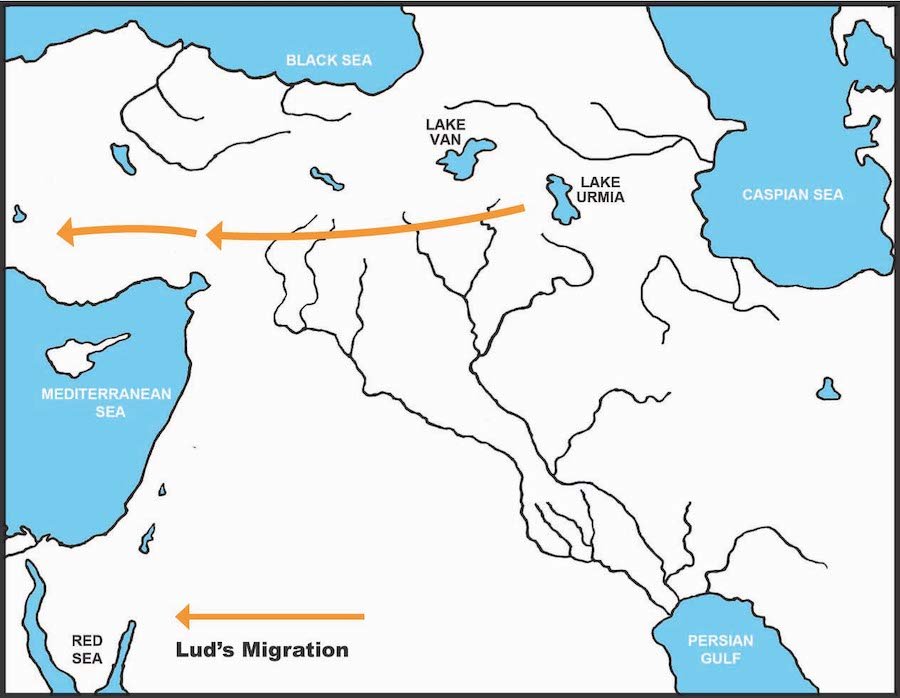

The last of Shem’s sons Lud is not easily located, but the later evidence places him en route to western Anatolia at this time, possibly being represented by one of the as yet undefined cultures of SE Anatolia. This is the site where the Bible places Lud’s descendants who are referred to as Lydians in English translations of the Bible, a name that is associated later with the Indo-European invaders who later settled there (end of Early Bronze II) but who were not the original people.

One of the clues to Lud’s presence in that region is the genetic marker Y chromosome J, which is very strong in all Shemitic (Semitic) groups and shows a strong presence in the early days of western (particularly SW) Anatolia, with a later spread westward. Lud’s presence is most likely suggested by the ‘early’ Chalcolithic people and their predecessors found at such sites as Beycesultan (fig. 11). The pottery in this period shows some similarity to Early Chalcolithic Hacilar and the more-easterly Konya Plain. It was replaced by a dark, burnished ware, considered by Seton Lloyd and James Mellaart (1962, 71) to be inferior to the earlier pottery; but which we can relate to some of the people around Cilicia/N. Syria, the latter reflecting early descendants of Javan before their major migrations. This is one of Lud’s possible legacies.

Fig. 11. Lud’s migration.

A Detailed Look at the Sons of Shem

We will now turn our attention individually to the sons of Shem in more detail.

1. Ubaid ‘Period’ (Arphaxad)

The Ubaid cultural ‘period’ is named after a site in southern Iraq called Al Ubaid where a particular type of early pottery was found. The same pottery was then found at Eridu, Ur, and the lowest levels at Uruk and was judged to be one of the earliest cultures in southern Mesopotamia. A not-dissimilar pottery culture was found in the Susiana area of what was later identified as Elam, but it was recognized as separate from the Ubaid culture.

The key to understanding the Ubaid culture comes from Ur, which is known in the Bible as “Ur of the Chaldees” (Genesis 11:28, 11:31, 15:7; Nehemiah 9:7), the native city of Abram (later Abraham). Additional information about the Ubaid culture is revealed by the early literary relationship of Eridu and Ur to the post-Flood Sumerian story and the fact that those areas were the areas of the Semitic Chaldean language. Claims have been made that Ur in southern Iraq is not the city of the Bible. But there is no doubt that the Assyrians recognized the area south of the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates as the home of the Chaldean people. Assyrian records are replete with references as such to this area.

Abraham’s earliest post-Flood ancestor was Arphaxad, son of Shem. Therefore, the Ubaid culture was most likely the earliest culture of the descendants of Arphaxad. As we shall see, it is the base culture of the expansion of the Semitic-speaking South Arabian people. Later, an expansion of the Ubaid culture took place northward over much of Mesopotamia. The moment of northern expansion also gives us a clue as to the moment of the early dispersion from Babel after the confusion of languages: “At all sites so far investigated in the South the Ubaid remains rest directly on virgin soil, and there seems little doubt that the people who bore this culture were the first settlers on the alluvium of whom we have any trace” (Perkins 1949, 72).

The Ubaid ‘period’ then is generally divided into four phases, 1–4, the first two labeled respectably as Eridu (Ubaid 1) and Hajj Muhammad (Ubaid 2). Ubaid 1 and Ubaid 2 are also represented in the earliest phase at Uruk (Warka Levels XVIII–XV,1 with some into XIV—Biblical Erech). At the site of el ˈOuelli, however, there appears to be an earlier phase which has been called Ubaid 0; it may represent the very earliest settlement.

At Uruk, Ubaid culture becomes admixed and then superseded by the Uruk culture; soon after which, we see an expansion northward of the Ubaid culture as we also witness the next two phases (3 and 4) in other cities in the south which correspond chronologically to the northern Ubaid expansion. That the dispersion from the time of Babel occurred at the end of Ubaid 2, where we see the beginning of the northern Ubaid expansion, gains traction with the findings of Hajj Muhammad pottery (Ubaid Phase 2)2 at Tell Brak in the Habur region, suggesting that Ubaid southerners had now arrived there.

From pottery sequences, it appears that the Ubaid culture came initially from north of the Zagros around the Lake Urmia region, perhaps illustrated best by Yanik Tepe. In fact, it appears that an early relationship can be established with this region for all the Mesopotamian settlers from Shem (Halaf, Hassuna, Samarra, Susiana, Ubaid). But then, this is the region from which we would expect the survivors and their descendants from the Ark to have come. David Rohl (1998, 136–139) maps a course for them in which they all initially pass south, particularly around Tepe Guran, Sarab, and Giyan. But, I believe that this can only be applied to the two southern groups, Susiana (from Elam) and Ubaid (from Arphaxad). The others came more directly to the Mesopotamian Plain via more northerly routes to the settlements of Halaf, Hassuna, and Samarra (which will be mentioned in those sections). The original pottery has therefore come from the family of Shem’s descendants but with individual variations and with clear, basic, early relationships. Le Breton (1957, 84) makes the following argument in regard to Susiana, Ubaid, Samarra, and Halaf:

Uniformity in unpainted pottery suggests that the first settlers in both areas shared the same culture and came from the same region; diversity in painted pottery, that they separated before the diffusion of the technique, regional styles developing autonomously but with reference to a common background of traditions, symbolic and formal.

All these pottery styles are from the sons of Shem. Ubaid and the Susiana pottery groups arrived steadily, and perhaps in waves via Tepe Guran and close areas, passing via the Kerkha River Valley to Khuzistan and then to their settlements in the plain. The time taken for these settlements, however, has been grossly exaggerated by virtue of the conventional chronology and the unnecessary sequential arrangement. For, as I am outlining, there is good reason to place as contemporary Ubaid 1–2, Susiana a–c, Samarra, Early Halaf, and pre-Halaf Hassuna3 and to place them prior to and up to the earliest Uruk XIV–XIII levels, which witness the appearance of the Uruk culture in the Plains later than the Shemitic descendants.

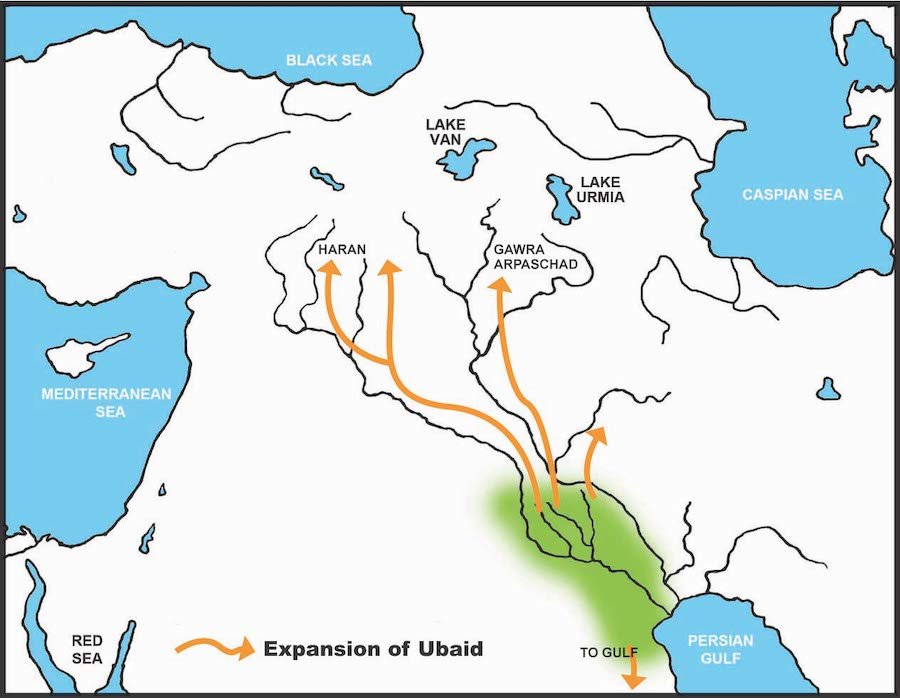

Soon after the arrival of the Uruk cultural people, whom I will identify with the personages of Cush and Nimrod (Sumerian MeshkiagKASHer and Enmerkar); we begin to see a significant dispersion of people from the south, which I believe has much to do with the Babel incident and confusion of languages. We see the Ubaid culture pass down into the Saudi Arabian shore of the Persian Gulf as far as Oman, and a northern dispersal and movement of Ubaid as far as Tepe Gawra and Harran, superseding, at least as witnessed by the pottery culture, the preceding cultures but contemporary with Uruk levels (and cultural period) XIV–IX and Ubaid 3 and 4 in the south. This was the first cultural expansion. This is then superseded by the expanding Uruk Culture over much of Mesopotamia (Uruk VIII and later) (fig. 12). This was a second cultural expansion.

Fig. 12. First expansion of Babel.

The expansion down along the Persian Gulf should be seen as the migration of the South Arabian groups progressively passing around the Saudi Arabian shoreline. These groups are connected with the names of the descendants of Arphaxad’s descendant Joktan (Genesis 10:26–29). The Chaldeans of southern Iraq (perhaps best illustrated by the Marsh Arabs today) would be later referred to as Bit Iakin by the Assyrian kings (Beth Jakin in Hebrew—“the House of Jakin”). I believe this is a reference to ‘Joktan.’ Notably, the South Arabian peoples are recognized as speaking various Semitic languages.

The northern expansion was wide and so was their trade with others, but of particular interest is the fact that the Balikh tributary area of the Euphrates, biblical Padan-Aram (the tableland of Aram), which was initially settled by Halaf (Aramaic) cultural people, now becomes dominated by Ubaid. And this is likely to be the case when Terah, Abram, and family soon move there. The point being, that as a result of there being people of the same culture now present in Harran, the temptation for Terah and family to be detained there would be strong.4 This Ubaid settlement in the Balikh valley would naturally take some “Chaldean” people (‘Kasdim’) to this Aramaic area, but this movement was well after the initial settlement in the south. They also took the moon god of southern Ur (that is, Nanna) to Harran, where consequently that worship became enshrined. Such worship is alluded to in Joshua 24:2: “Thus saith the LORD God of Israel, Your fathers dwelt on the other side of the flood [Euphrates] in old time, even Terah, the father of Abraham, and the father of Nachor: and they served other gods” (KJV). Northern Ubaid was contemporary with the Leyla Tepe cultural complex of the South Caucasus, which is highly likely a proto-Iranian culture.

2. Susiana (Elam)

Susiana is the region east of the southern portion of the Tigris River and west of the southern Zagros Mountains. It later became the region most strongly recognized as the area of ‘Elam,’ and, as such, we connect it clearly with the son of Shem—‘Elam.’ However, it would be a mistake to see only the Susiana region as constituting Elam’s descendants, for initially there is evidence that the early Elamites spread widely from east of the Lower Zab and down as far as the hinterland of modern Fars. But the cultural early entity that we are now concentrating on is best illustrated in Khuzistan (i.e., Susiana).

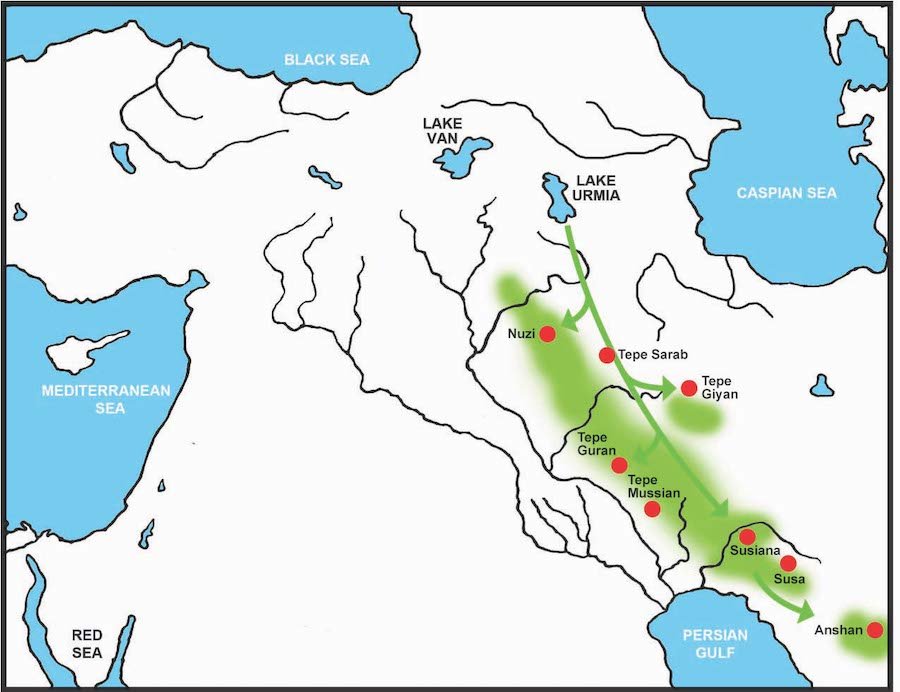

It is possible to follow Elam from the Urmia region, down via Tepe Guran and Tepe Giyan (perhaps also including Matarrah in the migration), down to the Khuzistan area via the Kerkha River Valley to Tepe Bandibal, Tepa Jowi, Buhallan, and Tepe Jaffarabad, and then later to Susa for the settlement of many of the descendants of Elam (Le Breton 1957, 84–86) (figs. 13 and 14).

Fig. 13. Migration of Elam and early settlement areas.

Fig. 14. Earliest settlements of Elam in Khuzistan.

However, as we see the later history of Elam, it is obvious that the settlements of these people were stretched out over an area from southeast of the Lesser Zab through to Khuzistan and deeper into Fars. For we will meet the regions later to dominate: Hamazi (most northwesterly), Awan (possibly just north of Khuzistan), Shimaski (most likely the more mountainous regions of the Zagros behind the Piedmont), Susa, and Anshan (area of Fars).

The Susiana Period (a, b, c, and d [from bottom up]) before the habitation of the city of Susa itself corresponds to the period of Early Ubaid on the Plain. Susiana ‘e’ corresponds to Susa 1 (A) (Le Breton 1957, 84–86); and Period B at Susa sees the influence of the Uruk culture, which is highly likely to have been not just cultural sharing but an invasion and control, and the name of Enmerkar (Nimrod) is the likely candidate. Tepe Sialk on the plateau (which may have been part of the area from where the early Shimaski rulers came) also exhibited similar culture to Susa and experienced the same invasive event as Susa—almost certainly from the Uruk culture (Ghirshman 1954, 46).

During the Early Dynastic period, Elam came into prominence with interactions with Sumer, both from the region of Awan (Deh Luran area) and Hamazi (north of the Diyala). Elam’s prominence ended at the beginning of the Early Dynastic III, very likely with the attack of Eanatum (probably aided by Enshakushanna of Uruk) who “drove the Elamite back to his own land” and defeated the king of Akshak, apparently close to the southern border of Hamazi (Cooper 1986, 41–42). Over the next centuries, the Elamites would react with the Indus Valley, BMAC civilizations in Turkmenistan and Afghanistan, as well as the mountain tribes: the Guti and Lullubi. They also had repeated interactions with Sumer, Akkad, and Babylon.

3. Halaf (Aram)

The Halaf culture is one of the recognized northern Chalcolithic cultures of Mesopotamia. The significant earliest places of settlement of the Halaf Period appear to be at Arpachiyah and Tepe Gawra close to the Tigris (the Mosul region today) (Perkins 1949), but Halaf-type pottery has also been found at the more-easterly site of Banahilk along a tributary of the Greater Zab (Braidwood et al. 1983, 549). The later range of the Halafian pottery culture coincides almost exactly with the settlements of the Aramaic people, which are almost certainly the settlements of the descendants of Shem’s son Aram. The earliest finding of Halaf pottery was at Tell Halaf in the Khabur Region (the type site) (Lloyd 1978, 66–67). This region is known in the Bible as Aram Naharaim (Genesis 24:10; Deuteronomy 23:4; Judges 3:8). Its later influence spread to the Balikh River Region known in the Bible as Padan Aram (the Tableland of Aram). As a result, I believe we can confidently claim Halaf culture as essentially that of the descendants of Aram, son of Shem.

The migration to this area initially preceded Babel (as I have defined and mentioned under the section on Ubaid), and we can almost certainly trace their initial movements from the western area around Lake Urmia along the tributaries of the Greater Zab. With initial settlement at Banahilk, then Arpachiyah and Tepe Gawra, spread would occur then from these settlements: “To capitulate, it seems to the writer that the Mosul area is likely to be the approximate original home of the Halaf culture and that from that area its influence went out in several directions” (Perkins 1949, 44) (fig. 15).

Fig. 15. Settlement and dispersion of Halaf.

The early phase of Halaf was contemporary with the Hassuna culture situated a little further south at Hassuna and Yarim Tepe; but a little later, it appears that Hassuna itself was culturally overwhelmed by the apparently stronger Halaf culture (Level VI) (Lloyd 1978, 69). The Halaf culture then becomes apparent in a wider area and expands to be evident also in Nineveh Phase 2c (the upper phase of Level 2, labeled from the bottom up) (Perkins 1949, 26). It became dominant in the Khabur headwaters and then into the Balikh Valley, but it is also found into the Amuq and as far as Cilicia and Ras Shamra. In the north, Halaf culture is found in the Keban area of present-day Turkey and near Lake Van at Tilki Tepe (Braidwood et al. 1983, 549). How much of this was cultural dominance and how much was trade and simply pottery cultural influence is not entirely defined, but several of these areas would see Aramaic settlement to a lesser or greater degree.

The Khabur headwater region would become an Aramaic stronghold even into Neo-Assyrian times, despite at times being dominated by surrounding people. Areas to the south and west of the Euphrates bend would also be heavily Aramaic and would see such Aramaic cities as Ebla and Halab (Aleppo). Josephus associates these kingdoms south and west of the Euphrates with Aram’s son Uz (Josephus 1987, 37). This region experienced the first appearance of Halaf culture, corresponding in time to Neolithic 4 (contemporaneous with Pottery Neolithic B-PNB) of Palestine (Moore 1982), and, as such, most likely represents the expansion of Aramaic people in quantity to that region. It is also possible that this appearance was the time of the beginning of Gobekli Tepe, which Dimitrios Dendrinos (2016, 2107) argues strongly was built after the PPNB, and possibly long after—contrary to present popular opinion.

The area around Lake Van (Tilki Tepe and other sites found close by) would become the area from which the Hurrians and later the Urartians would arise, and, again, Josephus (1987, 37) relates these people to Hul, the son of Aram. It is of interest then that the Hittites knew the Hurrians as the Hurlili, a name which would not be difficult to derive from Hul. One of the chief gods of these later people was called Haldi or Khaldi, and the name could easily be related to their forefather Hul, then being seen as their patronymic god (as was the case with the Assyrians who worshipped Ashur: their forefather’s name being Asshur in the Bible). The Hurrians’ language was not Aramaic but a separate group. Present-day Armenians (related region) trace part of their descent from Aram and have legends resulting from their dispersion at the time of Babel, as earlier mentioned. Areas further afield, such as the Amuq and Cilicia, however, were not settled by Aramaic peoples, but they traded with them during the time of the Halaf pottery culture and appeared to copy their wares: “The Cilician EC [Early Chalcolithic] sample is characterized by local painted wares, including some Halaf imitations and a few imports” (Steadman 1996, 148).

Sometime following the dispersion from Babel, the Halaf-type culture would be overwhelmed gradually by the Northern Ubaid, which reflects interaction and admixture with descendants of Arphaxad dispersing from the south. This Ubaid culture would become very prominent at Arpachiyah and Tepe Gawra but would also be so in the Balikh region, where the descendants of Abraham’s father Terah would later also settle, leaving their names in such cities as Harran, Nahor, Serug, and Terah (Til Terakhi). It is to here that the Bible refers when Joshua states, “Your fathers dwelt on the other side of the Flood [Euphrates] in old time, even Terah, the father of Abraham, and the father of Nachor: and they served other gods” (KJV). We know that the Ubaid people, Abraham’s cultural entity, took the moon god of Ur “Nanna” to Padan-Aram. Such worship was evident in Harran.

We can follow the migration of Halaf in its various places. The Sinjar region is typified by Yarim Tepe, and, according to Patty Jo Watson (1983, 234), Yarim Tepe II exhibits Early Halaf, followed by Middle and Late Halaf at Yarim Tepe III. In the Khabur region, again we find Early-to-Late Halaf, especially as exhibited at Tell Halaf. In the Balikh Valley, we find possibly Early but definitely Middle-to-Late Halaf, suggesting that Halaf arrived there a little later than the Khabur. Middle Euphrates appears a little later (Carchemish, Til Barsib, and Arslan Tepe near Malatya), and most sites appear to have Late Halaf pottery.

The north, as exhibited at Tilktepe near Lake Van and Girikihaciyan west of the Tigris headwaters, exhibits Late Halaf. It is likely that this Late Halaf culture represents the migration of the families from Hul, son of Aram, and the progenitors of the Hurrians and Urartians. Western Halaf, near Tell Rifaat near Aleppo and the surrounding area, and possibly the basis of Ebla (the Syro-Cilician area), exhibits Middle Phase Halaf. Its appearance there corresponds to the time of Pottery Neolithic B (PNB—Neolithic 4). This area is where the families of Uz, son of Aram, settled. Gobekli Tepe is likely built by these people, coming after a previous PPNB settlement in the area. The other sons of Aram are most likely represented first by the Samarran culture and are discussed with that culture.

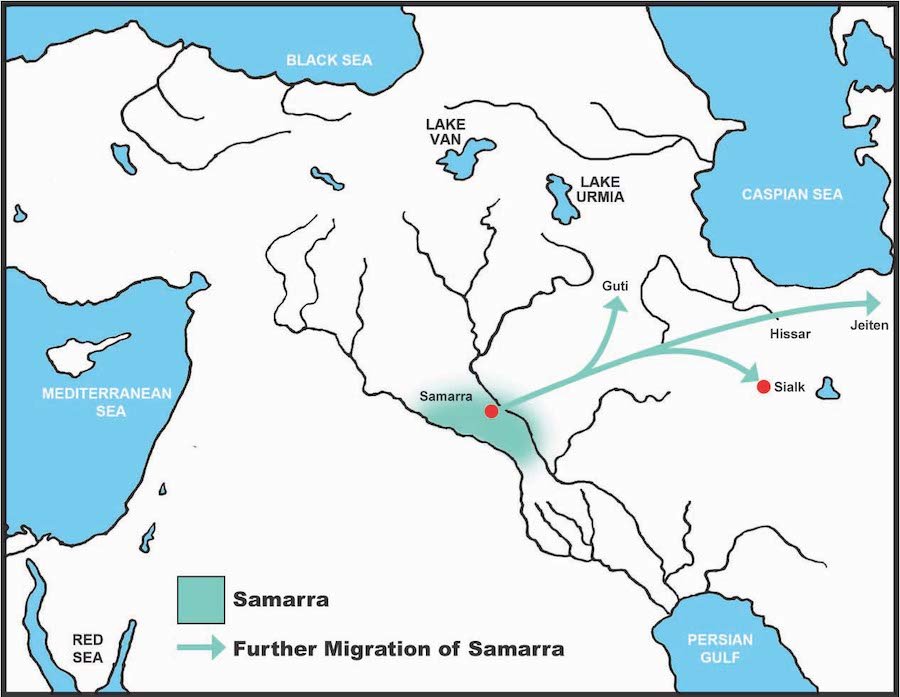

4. Samarra (Gether and Mash)

The Samarra cultural entity represents a separate Early Chalcolithic entity in the mid-Tigris area. It has been found in the east to encompass Choga Mami near Mandali on the border frontier of Iran. It extends westward to Baghouz on the Euphrates. The Samarra culture was first identified at Samarra and Tell es-Sawwan on the Middle Tigris north of Baghdad and the Adheim river tributary (fig. 16).

Fig. 16. Further migration of Samarra.

Samarra is separate from the Ubaid and Susiana cultures to the south and from the Hassuna and Halaf cultures to the north, yet it shows features that relate the pottery styles in many respects to one another (Le Breton 1957, 84–86). Samarra has been shown to be contemporary with Ubaid 1 and 2, Susiana a and b, and Early Halaf and Hassuna; although, earlier these were believed to represent different time periods.

Some difficulties have been expressed in identifying the origin of the Samarra culture. Some have suggested that an Iranian origin was possible, and certainly some relationship with early Iranian pottery has been cited. But Le Breton (1957, 86) has pointed out that, “the theory that Samarra is Iranian rests largely on design analogies with later wares and is not borne out by early evidence from South Iran; conversely, its native character has been stressed at the expense of its Iranian connections” (emphasis mine). Perkins (1949, 7) makes the following comment in regard to a particular pottery style: “The fact that this technique was very common in the Iranian Highlands is one of the major reasons for considering Samarran pottery as Iranian in character and presumably in origin.” The problem here is that the direction of migration has been mistaken. And the elements can be better related if we understand that at the dispersion of Babel, Samarra culture ceases in the main, but elements related to it now appear (and thus later) in Iran in Sialk, Qom, and especially at Hissar Level I. It then is to be found in Turkmenistan at Jeitun, then also at Kelteminar. Okladnikov (1990, 41–96) informs us that Kelteminar culture indicates connections with neighbors Jeitun, Namazga-depe, and Kara-depe; and some of the stone implements have similarities with the Jebel Cave in Turkmenistan and with Jeitun.

This then opens the way for the identification of the origin of the Samarra culture, and this is found in Josephus’s (1987, 37) claim concerning the sons of Aram, Gether, and Mash: “Gather [founded] the Bactrians; and Mesa the Mesaneans; it is now called Charax Spasini.” Josephus is, of course, referring to the later Hellenized region known to the archaeologists as the ‘Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex’ (BMAC), otherwise known as the Oxus Civilization. The two names Mash and Gether are revealed in the later name of the inhabitants of that region—the Massagetae. Such an identification then allows us to conclude that Samarra was a settlement of the Aramaic sons Gether and Mash (Genesis 10:23), and the Oxus Civilization was then, initially, a Shemitic people, a family from Aram, son of Shem. A Semitic base for the Oxus Civilization appears to be confirmed by the high levels of the largely Semitic Y-chromosome haploids J* and J2 as well as the related (possibly sibling) haploid L found in ancient skeletons, which remain even after some irruption into their culture by the R-carrying Indo-Europeans (Narasimhan et al. 2018).

Christoph Baumer (2012, 73), in discussion of the BMAC-related sites of Sarazm, Altyn Tepe, and the Geoksyur Oases, states the following: “Like the inhabitants of the northern foothills of the Kopet Dag and the Geosyur oases, these people were Europids of the Mediterranean type.” Again, such characteristics align the inhabitants at that time to the West-Asian area heavily settled by Shem’s descendants. This identification then also opens the possibility that the early hill people, the Guti (and possibly Lullubi and Simurrum people) who harassed the Akkadian Empire, were, in fact, descendants of Gether. Certainly, there is a linguistic possibility, and the geography now makes sense. Genetic studies in the region where the Guti lived, which is now heavily Kurdish, have confirmed similar genetics with high J2 (Flores et al. 2005; Gokcumen et al. 2011), and some believe that the Kurdish people have incorporated the earlier Guti (which may well be a linguistic factor in the name of the Kurds) with later admixture of the Medes and others. The Samarra culture also has an affiliation with Matarrah to the north (Lloyd 1978, 71). This may well have been a stop for some of them on their way from the Lake Urmia region to their later Tigris-centered settlement.5

Samarran pottery has been found in association with Halaf pottery—which I associate with Aram— certainly at Samarra itself and also at Nineveh Stratum 1 and 2 (Perkins 1949, 9). Samarran pottery is also found with a Halaf piece at Tell Arpachiyah in level TT10 along with Halaf pottery: This tell is one of the earliest settlements of the Halaf people. At Tell Shaghir Bazar in the lowest level, Halaf and Samarran pottery are both found. Perkins (1949, 13) comments when referring to Tell Halaf, “We have mentioned that the Samarran pottery seems to occur in a Halaf-period milieu.” It is also noteworthy that Samarran pottery appears contemporaneous with Hassuna—which I associate with Asshur—and as Perkins (1949, 1) explains: “Hassunah is a stratified site with a fair volume of material, including some of the famous Samarran painted pottery.”

It would then appear that the families of Aram and Asshur moved southwest from the Urmia area prior to Babel: Aram very likely following the valleys associated with the Greater Zab, settling first around Arpachiyah and the area of Mosul; and Asshur following the Lesser Zab a short distance south, west of the Tigris. The sons of Aram, Gether, and Mash, then moved down slightly southeast on the eastern Tigris area, having a connection with Matarrah, but most likely then following the valleys along the Adheim River to their settlement slightly above its conjunction with the Tigris. Each of these families show some pottery similarities with their painted wares, but they definitely express their family individualities.

As indicated above, the Samarra culture appears to disappear towards the end of the Ubaid 2 (Hajj Muhammad) Period (a moment at which I place the beginning of the Dispersion), but similarities of some of its cultural assets now appear in the northern Iranian highlands, particularly at Tepe Sialk and Hissar Level 1 (Schmidt 1937), Tureng Tepe, and then Jeitun in southern Turkmenistan, from whence it expanded semi-locally. It is also possible that this route led to the early Helmand culture, particularly as represented at Mundigak and later at Shahr-e Sukhteh. These centers soon began interacting with the Jiroft culture further south as well as the Indus culture to the east and with the above cultures in Turkmenistan.

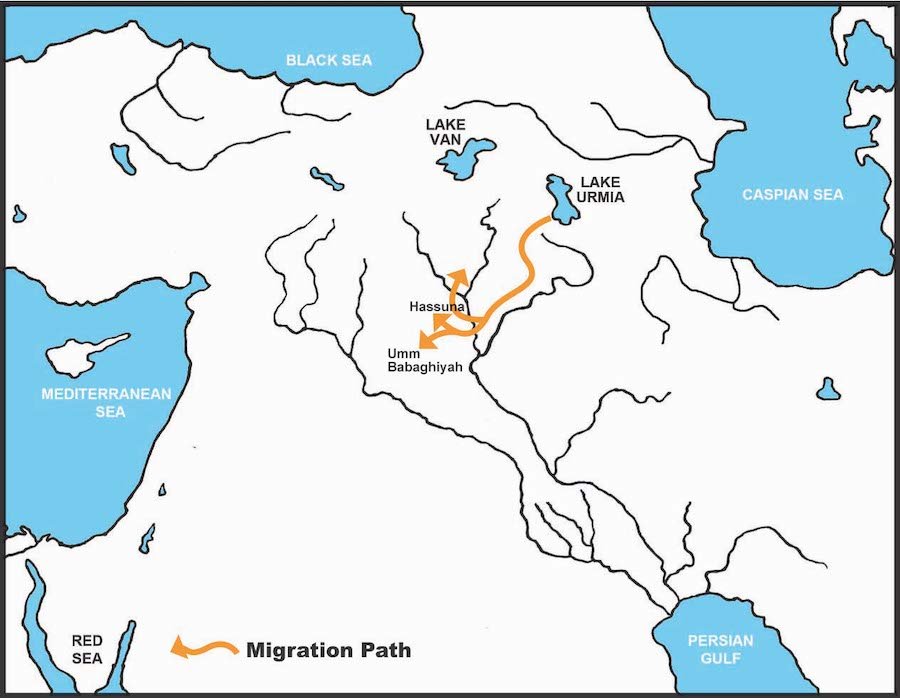

5. Hassuna (Asshur)

Hassuna is another of the recognized northern Chalcolithic cultures of Mesopotamia and was contemporary with Early Halaf and Samarra (Oates 1983, 251–281). Its cultural wares can be found at Hassuna, Yarim Tepe I, Umm Dabaghiyah, and also at Nineveh Level I. Its wares would also be found easterly at Jarmo, south of the Lower Zab, which almost certainly lies on the migration path from the Urmia District to the Mesopotamian Plain (fig. 17).

Fig. 17. Settlement of Hassuna culture.

Hassuna and its related cultural environs are almost certainly the areas of initial settlement of the descendants of Asshur, son of Shem, which would later become the recognized area of the Assyrians. But it also would be the area of the resettlement of Nimrod, coming from the south and his earlier area of control (Genesis 10:8–12). Nimrod’s influence would become evident in Uruk, migrating north to influence Level IV at Nineveh and then the much-argued-over Ninevite V Level and wares.6

Hassuna and related settlements, particularly Tell Sotto which witnesses an earlier pre-Hassuna phase following Jarmo, appear to be the first expression of fixed settlement in the Sinjar and northern Jazirah area. But there is evidence of earlier people who have been thought to have been nomadic whose pottery cultures suggest relations with Sakçagözü in Turkey as well as Amuq B and Amuq A–C (Perkins 1949, 11). All of this suggests other families passed through, and the descendants of Phut and Mizraim are here suggested.7 Hassuna then is the area of the initial settlement of Asshur’s descendants, but it appears soon to have been temporarily overwhelmed culturally by the closely-settled Halaf people (Aram) Level VI–X8 (Perkins 1949, 25). Hassuna-type culture was also found at Level 1 at Nineveh.

Later, we are told that Nimrod moved to the region of Asshur (Genesis 10:8–12), and this can be seen in the Uruk-type artifacts at Nineveh Level IV. Nimrod here began a large building program including Nineveh and Calah (archeologically known as Nimrud today). The Early Assyrian Period, as seen in the King List, gives evidence of at least three dynastic lines (which will also include the invading Amorites), and this is consistent with biblical expectations. However, to complete the study of Early Mesopotamia, we also need to look at the Uruk culture and Cush/Nimrod, even though this clearly brings in the family of Ham.

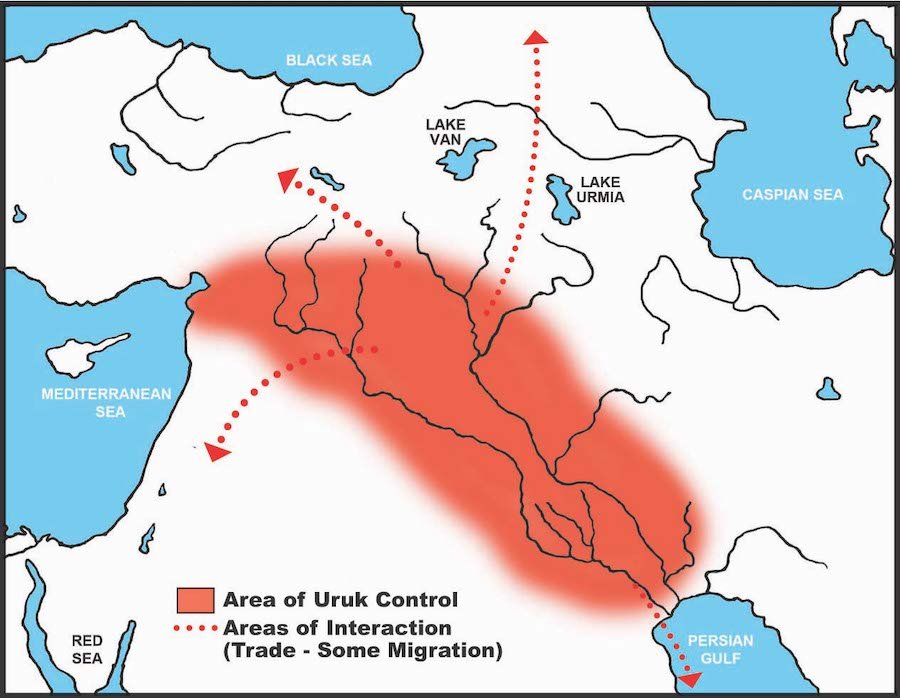

The Uruk Period

The Uruk Period of the Mesopotamian Chalcolithic will never be understood without the Bible’s historical record and particularly the record of Nimrod, grandson of Ham. In the Genesis record (Genesis 10:8–12), he is described as, “Nimrod the mighty hunter,” and it is stated that he was a significant builder of the ancient world. He was first involved in building Babel, Erech (Uruk), and Accad and Calneh in the south. Later, he moved north to the area inhabited by the descendants of Asshur (Assyria) and built Nineveh, Rehoboth, Calah, and Resen. These characteristics imply a powerful figure and perhaps a dictatorial one involved with a significant labor force and period of time to achieve these feats.

Archaeologist David Rohl has significantly discussed a Sumerian heroic figure Enmerkar who is recorded as living in the second generation after the Flood, as was Nimrod. He was the builder of Uruk, and his name when transliterated into the Semitic tongue can be rendered “NMRU the hunter”; and then into English as “Nimrod the hunter.” We therefore have an identity from both the Bible and the secular record that matches. It then becomes likely that a culture that we first find in the region of Uruk which becomes a strong regionally-embracing culture should be connected with such an individual. And such a connection brings much clarification into the picture of the Uruk culture.

But to understand the period, we need to jettison the long-age assumptions that have for too long underlain the discussion of this period. The present length of time placed over the basic ‘periods’ of the Mesopotamian Chalcolithic is usually cited as about 2,000 years. This time is described as succeeding, separate periods like “the chests of a drawer,” to quote Joan Oates (1983, 254), which develop from simple and primitive to complex. But of recent years, this concept has taken a beating as many have come to realize that these ‘periods’ have often overlapped and been contemporary. In fact, if the biblical model is employed, the common-sense result is that the cultures described as Ubaid, Susiana, Samarra, Hassuna, and Halaf in their initial phases were all contemporary and represent the first establishment of the sons of Shem in the Land of Sumer. Sumer is Shumer in the cuneiform documents and Shemer in Hebrew, which becomes Shem with the unpronounced, ‘amissible’ consonant ‘r’ being dropped (Rohl 1998, 133–135). Biblical Shinar is a derivative of the Egyptian name Sumer-Senaar. While the above can be recognized as descendants of Shem, a further and slightly-later-appearing culture, the “Uruk culture,” is found which appears not to be from descendants of Shem but from Ham. The Uruk culture arrived a little later, most likely from north of the Zagros Mountains.

We then need to realize that the biblical historical record allows a much shorter period for the Mesopotamian Chalcolithic and that we should speak of hundreds, not thousands of years, and most likely not much different from either side of 200 years. Such a shortening would no doubt be taken by surprise by many who hold the conventional chronology, but when the skill and intelligence of these people and the now-recognized contemporaneity of many of these cultures are taken into account, such surprise is misplaced. In discussion of ‘ages’ in archaeology, long periods are glibly assumed without thinking exactly how long these period in terms of human development really are. Few of us have experienced a lifetime of 100 years, yet most of us are familiar with great changes in our short lifetimes. If we strip away the naive evolutionary assumptions of human development, we should appreciate that early members of our race were just as innovative as we and just as resourceful, often with more limited materials, and that changes in smaller societies could just as well happen quickly.

Where then to begin the discussion of the Uruk culture? I would suggest that we need to look close to the site of the landing of the Ark following the Flood, and that is the area embracing lakes Van and Urmia and the Kura-Araxes valley. It is here that we come across an area just northeast of modern Tabriz with a mountain called Qusheh Dagh, the ‘Mountain of Cush,’ just south of the Araxes River. David Rohl (1998, 95–103) has, I believe, given a credible argument that this area is the “land of Cush” (translated Ethiopia in the KJV) of Genesis 2:13, the earliest settlement of Cush and his descendants (including Nimrod) after the Flood. This is not to be confused with the later settlement of these people after the dispersion from Babel—that is, the Sudan in Africa (referred to as Ethiopia in the rest of the KJV). Rohl (1998, 51–54) also points out that the Araxes River even in historical times has been referred to as the Gaihon (Gihon), the river mentioned in Genesis 2:13.

It is likely that as the ice period began to develop after the Flood, the mountains would have become less hospitable for some, and so they would have moved down into the plain. Such was the early action of the sons of Shem. But it appears that not too long after this, Cush and his sons followed, settling first in lower Mesopotamia near the Euphrates. Hallo and Simpson (1971, 44) have Enmerkar (Nimrod), son of Meskiagkasher (Cush), first settling in Kulab across the river from Eanna. He is referred to as “Lord of Kulab.” It appears that with the joining of Eanna and Kulab, we then have the beginning of Uruk (Erech). Uruk was first known as Eanna, the ‘house of An,’ ‘An’ being the ‘God of Heaven.’ Enmerkar claims to have ‘brought Inanna down from the mountains,’ (Kramer 1963, 270) to make An his female consort, so introducing the fertility rites into the early post-Flood world. So, it appears, began the ritual of the priestess representing the god and the beginning of temple prostitution under the concept of a “holy marriage.” This clearly is one of the historic events Paul referred to in Romans 1:21–23: “When they knew God, they glorified Him not as God, neither were thankful; but became vain in their imaginations and their foolish heart was darkened. Professing themselves to be wise, they became fools, and changed the glory of the uncorruptible God into an image made like corruptible man . . .” (KJV).

In fact, it appears that this act became identified with Enmerkar (Nimrod) and his wife/sister, for he is later referred to as Bel (the Babylonian form of Baal—later identified as Marduk) and Innana as the Semitic Ishtar, biblically called Ashtaroth, the consort of Baal. This myth spread across the known world after the dispersion so that Enmerkar, and perhaps to some extent Cush also, became involved in introducing the first idolatry after the Flood. Inanna is known later in Assyria and Babylonia as Ishtar (Semitic form), Astarte by the Syrians, Ashtaroth to Israel, Isis to the Egyptians, Durga to the Dravidians, and Aphrodite to the Greeks. And so the idolatrous cult spread around the world at the dispersion as a result of Nimrod’s actions. Cush (father of the dark Sudanese) and Nimrod (Semitic meaning ‘leopard’) can be seen in the biblical pun, “Can the Cushite [Ethiopian of the KJV] change his skin, or a leopard his spots?” (CSB). This pun teaches that rebellious, sinful man is incapable of saving himself.

The earliest levels at Uruk, as also at Ur and Eridu, are related to the early phases of the Ubaid culture. I connect the early phases of the Ubaid culture with Arphaxad, son of Shem, from whom came the Chaldean people and later the Hebrew and Arabic people as well as the Semitic South Arabian families. In the Bible, Ur is referred to as “Ur of the Chaldees” (Genesis 11:28, 31). We first recognize the Uruk culture—and by implication the family of Nimrod—in the archaeological record just before Uruk-Eanna Level VIII. The Uruk culture is strongly present in Level VIII soon after the end of the Hajj Muhamad Levels of the Ubaid culture (Ubaid 2). It is here that we should place the moment of the Dispersion, for now we find the beginning of the northern migration of Ubaid (Northern Ubaid) and the disappearance of Samarra culture.

At this stage, we can assume that Enmerkar (Nimrod) is ruling in Uruk. The original single language has now gone, and the south is faced with two inherent languages, Akkadian Semitic and Sumerian: the latter I attribute to the descendants of Nimrod. It appears that he is now consolidating his power, and soon we will see evidence of expansion and most likely invasions. This becomes evident in Uruk-Eanna levels VI, which has pottery very similar to Ninevite 4, and slightly earlier in Susa B to the east. I believe that Ninevite 4 represents the movement of Nimrod to Nineveh. No doubt, he would have left Uruk under the authority of his descendants: Lugalbanda, Dumuzi, and Gilgamesh (in that order, but who may also assume some degree of contemporaneous rule at Uruk).

Ninevite 5 almost certainly represents the presence and consolidated rule of Nimrod from Nineveh (with other culturally associated changes). This interpretation appears to fit with the archaeology: “Moreover, Ninevite V wares, including the painted variety, at both excavated and surveyed sites, are almost always found in association with Uruk pottery. This is true at such excavated sites as: Nineveh, Gawra, Ibrahim Bayis, the Dokan region, Telul eth-Thalathat, and Grai Resh. It is also true at nearly one hundred surveyed sites in Assyria” (Al-soof 1968, 75). Al-soof (1968, 76) continues, “We therefore feel justified in suggesting that the Ninevite V occupation, for which pottery at present affords our only reliable evidence, is a direct development of the Uruk occupation in the same area.” Moreover, Roaf and Killick (1987, 199–230) reach essentially this same conclusion (though in much more detail).

Levels V–IV at Uruk are considered the Late Uruk Period and are the time of the greatest expansion of Nimrod’s “empire.” They also appear to correspond approximately to the beginning of the geological Holocene Age (against a creation, post-Flood chronology; not the evolutionary, long-age chronology). During this time, the end of the ice period and the rise of the ocean (the Holocene Transgression) occurred. Water levels would soon overshoot present-day levels for a period of time and bring the waters of the Persian Gulf to the cities of Ur and Eridu. This was the ‘flood’ (oceanic) that archaeologist Leonard Woolley found at Ur (Oppenheimer 1998, 49–62).

Woolley’s Flood (better understood as an oceanic transgression), which particularly affected Ur (most other cities being left untouched), appears to have begun after Ubaid 3 and continued into Ubaid 4. In other cities, Ubaid 4 showed evidence of the presence of Uruk culture also. Soon after the Ubaid 4/Uruk levels found in the other southern cities, the Uruk (or second expansion) becomes evident. I have suggested that the appearance of Uruk culture indicates that the initial dispersion must have occurred after Ubaid 2 (Hajj Mohammad style and period) and likely into the Early Ubaid 3, where an Uruk presence can also be found. So, the soon-but-later Uruk expansion (sometimes called the second expansion) is associated with Enmerkar (Nimrod) and his surge to empire, particularly at and after his move to Nineveh. Moreover, this sea-rise flood began quickly, but it would take a considerable time for the oceans to recede to the present levels: not an overnight event.

The Uruk Period presents us with an extended empire: from Susa (for a period) to the eastern border of Cilicia; and into the Kabur region, south of the Ararat area (later known as Urartu) of Lake Van and Lake Urmia. It appears to be a significant trading empire, trading with peoples north of the Caucasus (the Maykop culture), to the Amuq in the northwest, to Elam (Susa) in the east (figs. 18 and 19).

Fig. 18. The Uruk empire.

Fig. 19. The journeys and routes from the Uruk empire.

Uruk’s influence clearly extends to the Jemdet-Nasr Period, with an apparent cultural merging. It is clear that not all people saw friendly relations with Late Uruk (which was no doubt under Nimrod’s leadership), for Cilicia appears to have closed its border to such trade and fortified its towns (Steadman 1996, 148). And, the area later called Armenia (Ararat of the Bible and contiguous with Assyria) was in a conflict according to legend which resulted in the death of ‘Bel,’ who is clearly identified with Nimrod in that legend—He is called the Titan Bel.

Enmerkar’s reign is quoted as 420 years, and this, of course, is taken with a high degree of skepticism. However, it is well to remember that his biblical Semitic contemporary Salah is given a lifetime of 433 years (Genesis 11:14–15), so that skepticism may not be so appropriate. Enmerkar was after all an extensive builder of many cities of the Ancient world. Such a lifetime would take him well into the time of the Early Dynastic 1 Period of Mesopotamia, where he would still be ruling in Nineveh. He may even be the once-mentioned king of Assyria before the time of Silulu (Sulili) called Bel-kapkapi (“the sling of Bel”), whom Adada-nirari III proudly proclaimed as his ancient ancestor, “whose glory Assur proclaimed from of old” (Luckenbill 1926, under “Section 743”). We may also be reminded that even in the days of the prophet Micah of the Bible (c. 700 B.C.), Assyria was still known as “the land of Nimrod” (Micah 5:6).

It is in the Late Uruk Period (Uruk IV) that early writing first appears, becoming prominent during its later phase during the Jemdet-Nasr Period. This is almost certainly not the first writing of mankind but the reinvention of a written form after the Flood and particularly after the dispersion from Babel. The fact that writing has not been found in horizons before Babel (and post-Flood) should not be a reason for the negation of such an already known cultural asset, for the people were heavily involved in pursuits of settlement and phases of settlement that did not yet require such a cultural asset. Soon after, other writing forms appear in other areas as people come to terms with the expression of their new languages.

Rohl (1998, 174) reminds us that the first historical mention of writing from Sumerian records is that of Enmerkar writing on a clay tablet to be taken to Aratta. And as we have placed Nimrod (Enmerkar) in the same period (Uruk IV), it is highly likely that his rule was a significant factor in the early development of writing in Mesopotamia. This means of communication, no doubt, now becoming indispensable for the expanded kingdom and its trading partners.

During this early period, we also find the art form known as ‘the master of animals,’ which depicts a person between two beasts, often lions. This form is usually attributed to Gilgamesh, but the form appears before his time. It is also present in artifacts found in Egypt attributable to the Late Uruk Period and associated with artifacts attributable to Mesopotamia. The logical consequence is that it, in fact, represents Enmerkar ‘The Mighty Hunter,’ who in historical (if not in literary terms) was the more prominent of the two figures and certainly the earlier. It seems that the prominence in modern circles of the Gilgamesh epic has overshadowed the historical reality in the mind of interpreters.

This Late Uruk Period also saw the appearance in Egypt, during the Gerzean Period, of Mesopotamian culture. I have suggested that this appearance in southern Egypt (in the area now called Pathros) announces the arrival of the last of the Egyptian descendants—the Pathrusim—now arriving via the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea (unlike the other six tribes). There are genetic, archaeological, and historical reasons to believe that Pathrusim, son of Mizraim (Genesis 10:13–14), arrived in that land later than the other Egyptian tribes and via a different route, one that involved lower Mesopotamia and Susiana around the Late Uruk phase. They arrived by sea and then the eastern wadis during the Gerzean Period and vitally affected the established population, leading to the stimulation of the Dynastic Period. Their appearance brings clarification into a long-established argument about the beginning of Dynastic Egypt. The Pathrusim are identifiable in the many petrographs in the eastern desert wadis which depict Mesopotamian vessels (mentioned by Rohl 1998, 136–139). These people, suggested as invaders by the petrographs, and which I identify as the Pathrusim, appear to have taken control of southern (Upper) Egypt as an elite group of rulers known later as the ‘Iry-Pat’ (the people of Pat = Pathrusim). They were the stimulus for the beginning of the Dynastic Period of Egypt.

The Uruk Period, or should we refer to it as an early empire, became a very significant factor in the development of several civilizations. Placed in perspective, it precedes and even rivals the later Sargonic (Akkadian) Empire, which up till now has held the academic world in some awe. It will also be obvious from the earlier discussion that I reject the identification of Nimrod with Sargon of Akkad. Nimrod is, as I believe Rohl (1998, 213–217) has powerfully proposed, Enmerkar, the earlier Sumerian hero.

Where Was Babel?

Many have wondered if there is any evidence to allow us to place the Tower of Babel. Skeptics have often claimed that the story originated in Babylon during Israel’s captivity and was formulated under the influence of Nebuchadnezzar’s Ziggurat at Babylon. Such is simply a whitewash to excuse the fallacious JEDP theory (Documentary or Wellhausen hypothesis), which claims late manufacturing of the Pentateuch. The theory comes from no evidence and has no credibility, but, sadly, it holds many of our biblical archaeologists in its grip.

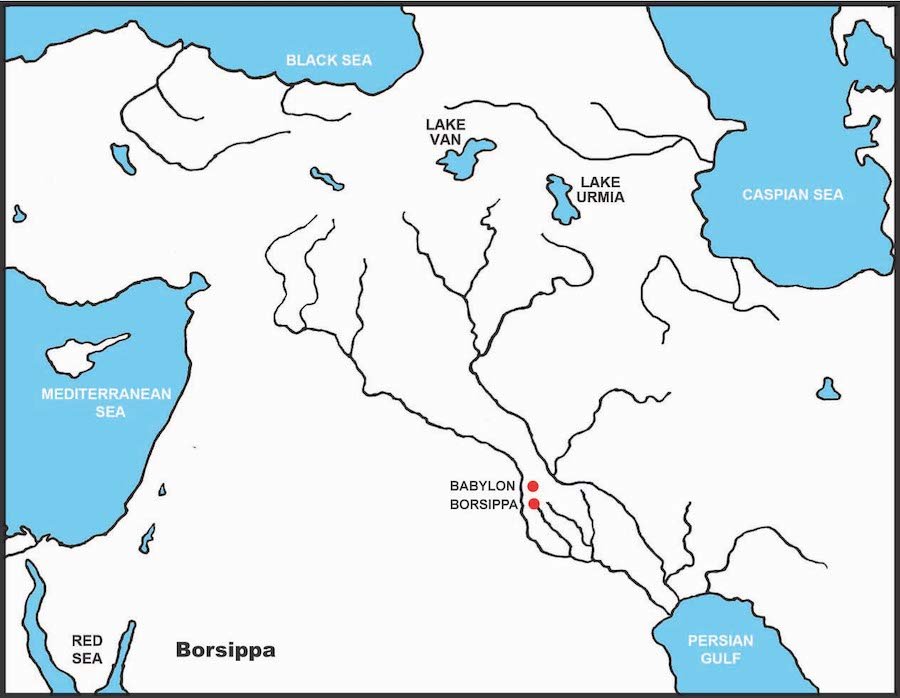

Some, including Iraqi guides, locate the Tower of Babel with Birs Nimrud, the ruins of Borsippa 11–12 mi south of Babylon, and within its early precinct. This is a smaller sister city to Babylon which shows the ruins of a ziggurat built by Nebuchadnezzar II, which was built over the ruins of a previous ziggurat—a fact claimed also by Nebuchadnezzar. Hammurabi of the Old Babylonian Period (circa 1450 B.C.-revised) did some building there, and it was a functioning center during the Ur III Period before 1660 B.C. (revised). As such, Borsippa has an ancient origin.

In 1921 in the Journal of American Oriental Society, John Peters (1921, 157–159) presented us with a discussion surrounding a clay cylinder unearthed by Sir Henry Rawlinson from the corners of the ziggurat of Borsippa. It was written by Nebuchadnezzar II about his restoration of the ruined ziggurat by a former king from a “time long since”: “At that time the house of the seven divisions of heaven and earth, the ziggurat of Borsippa, which a former king had built and carried to a height of forty-two ells, but the summit of which he had not erected, was long since fallen into decay . . . I built it anew as in the former times, as in the days of yore, I erected the summit.”9 It seems significant that Nebuchadnezzar, who had built a glorious ziggurat at Babylon, would also build this ziggurat close by at Borsippa (fig. 20).

Fig. 20. The location of Borsippa.

None of the kings of Ur III seemed interested in significant buildings in Borsippa, so the king referred to here was almost certainly earlier, and Nimrod (Sumerian Enmerkar) would certainly stand out as a significant possibility. Certainly, Borsippa stands out as one of the best possibilities for the original site of the Tower of Babel, but a guaranteed site is unlikely to be found.

References

Al-soof, Behnam Abu. 1968. “Distribution of Uruk, Jamdat Nasr and Ninevite V Pottery as Revealed by Field Survey Work in Iraq.” Iraq 30, no. 1 (Spring): 74–86.

Baumer, Christoph. 2012. The History of Central Asia. Vol. 1. The Age of the Steppe Warriors. Translated by Miranda Bennett. London, United Kingdom: I. B. Tauris.

Braidwood, Linda S., Robert J. Braidwood, Bruce Howe, Charles A. Reed, and Patty Jo Watson. eds. 1983. Prehistoric Archeology Along the Zagros Flanks. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications 105. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago.

Cooper, Jerrold S. 1986. Sumerian and Akkadian Royal Inscriptions. Vol. 1, Presargonic Inscriptions. American Oriental Society Translation Series. New Haven, Connecticut: The American Oriental Society.

Delson, Eric, Ian Tattersall, John A. Van Couvering, and Alison S. Brooks. 2004. Encyclopedia of Human Evolution and Prehistory. 2nd ed. Garland Reference Library of the Humanities. Vol. 1845. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Dendrinos, Dimitrios S. 2016. Gobekli Tepe: A 6th Millennium BC Monument. https://www.academia.edu/30163462/Gobekli_Tepe_a_6_th_millennium_BC_monument.

Dendrinos, Dimitrios S. 2017. “A Primer on Gobekli Tepe.” Academia.edu. January 21, 2017. https://www.academia.edu/31039270/A_Primer_on_Gobekli_Tepe.

Der Nersessian, Serapie. 1969. The Armenians. Ancient Peoples and Places. Vol. 68. Edited by Glyn Daniel. London, United Kingdom: Thames and Hudson.

Flores, Carlos, Nicole Maca-Meyer, Jose M. Larruga, Vicente M. Cabrera, Naif Karadsheh, and Ana M. Gonzalez. 2005. “Isolates in a Corridor of Migrations: A High-Resolution Analysis of Y-Chromosome Variation in Jordan.” Journal of Human Genetics 50 (September 1): 435–441.