The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

During his long lifetime, young-earth advocate David Down (1918–2018) championed a revised Egyptian chronology that claimed to correlate the pharaohs of Egypt with the historical text of the Bible. This revision was sourced in part from the vilified reconstruction of ancient history published several decades ago by the Russian-born catastrophist, Immanuel Velikovsky (best-selling author of Worlds in Collision 1950). Down’s chronology repeated Velikovsky’s hypothesis that Rameses III of Dynasty 20 ruled Egypt during the late Persian period—some eight centuries after the conventional date for his reign. His claim is scientifically testable using the archaeological principles of stratigraphy, in particular the law of superposition. For example, if Down’s hypothesis is valid, stratified artifacts inscribed with the name of Rameses III will not be found in deposits sealed prior to the late Persian period.

This paper examines the ancient remains at Tel Lachish—a mound ruin in modern Israel—to show that archaeological stratigraphy conflicts with Velikovsky’s unconventional theory concerning Rameses III. That conclusion, in turn, creates difficulty for the framework of Down’s revised Egyptian chronology, including his central claim (originally proposed by Velikovsky) that Thutmose III of Dynasty 18 was King Shishak, who plundered Solomon’s temple.

Keywords: Egypt, chronology, David Down, Velikovsky, Rameses III, Tel Lachish

Introduction

The last powerful king to control the fading Egyptian Empire was Usermaatre-Meryamun Rameses-Heqaiunu (Beckerath 1999, 164–167; Leprohon 2013, 127–130)—better known as Rameses III—the second Pharaoh of Egypt’s Dynasty 20 (for a chronological list of New Kingdom pharaohs, see Appendix D). During his reign, armies defending the Nile valley were bloodied in brutal wars, incised in magnificent reliefs on the walls of his great mortuary temple at Medinet Habu near Luxor (Breasted 1930, 1932; O’Connor 2000, 2012). These inscriptions describe a massive invasion by a coalition of so-called Sea Peoples (Cline and O’Connor 2012; O’Connor 2000; Redford 2000; Weinstein 2012), whom Rameses III repulsed in a series of fierce battles in Year 8 of his reign (Bryce 1998, 370–371; Grandet 2014, 4–6; Van Dijk 2003, 297–298). Mainstream archaeologists date this conflict to the end of the Late Bronze Age (after c. 1200 BC), linking these invaders to marauding and migrating people groups from the Aegean islands, coastal Anatolia, Cyprus, and Crete (Barako 2003; Bryce 1998, 371–374; Cline and O’Connor 2012; Haider 2012; Mazar 1992a, 302–306; 1992b; Stern 2014; Yasur-Landau 2012).

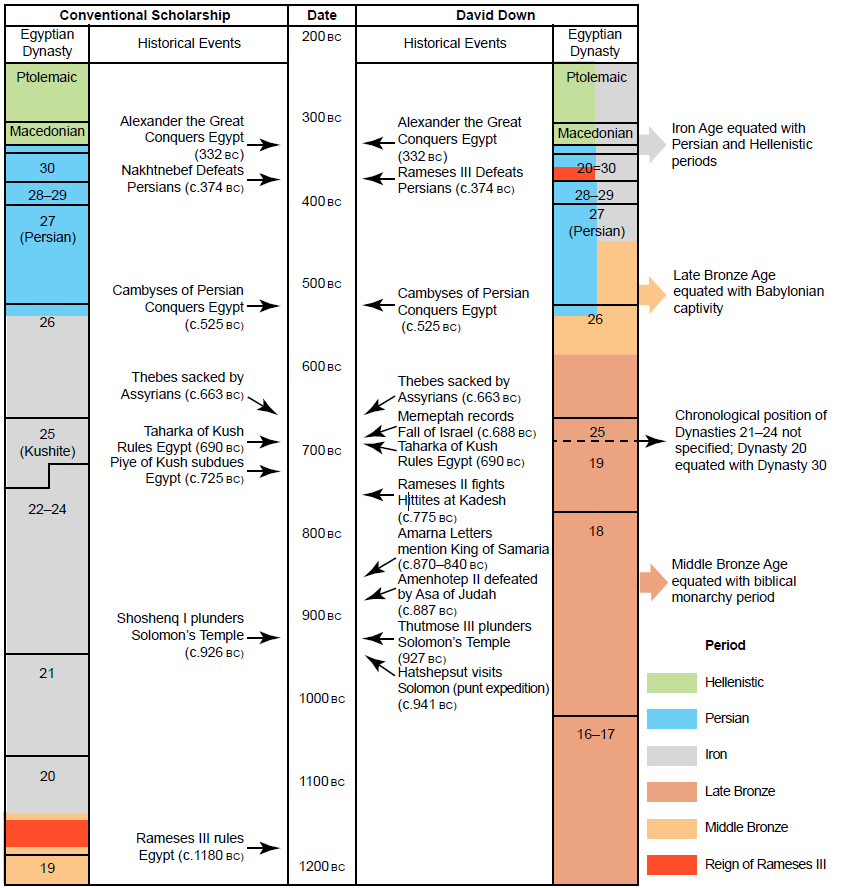

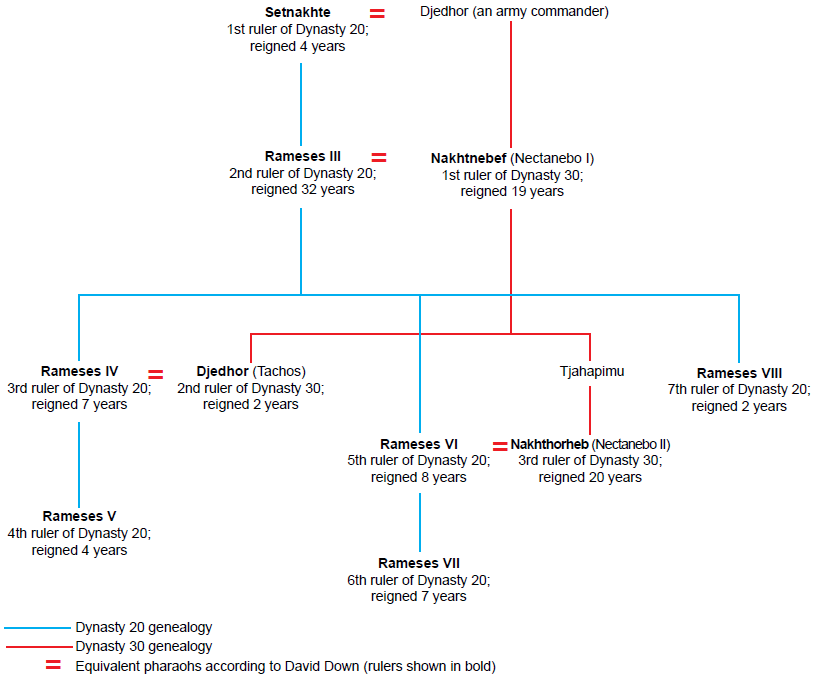

In contrast, Australian field archaeologist David Down, former publisher of Archaeological Diggings (1994–2013), has disagreed with the conventional date for Rameses III’s reign and the academic consensus regarding the identity of the Sea Peoples. In his book Unwrapping the Pharaohs (co-authored with John Ashton 2006), Down claimed that scholarly literature had misdated Rameses III by as much as eight hundred years (see fig. 1). According to this view, the Medinet Habu inscriptions record a battle between the Egyptian army of Rameses III and an invading host of Persians and Greeks. This battle took place in 374/3 BC, when an obscure king named Kheperkare Nakhtnebef (Beckerath 1999, 226–227; Leprohon 2013, 171–172) ruled Egypt (Clayton 1994, 201, 203; Cook 1983, 325–326; Diodorus 1952, 63–69; Gardiner 1961, 365–366; Grimal 1992, 375–376; Lloyd 1994, 343; Perdu 2010, 155; Ussher 2003, 199). Down became convinced that Rameses III is the same person as the embattled Nakhtnebef (see fig. 2), whom the Greeks called Nectanebo I1 (Ashton and Down 2006, 180–181, 193, 210; Diodorus 1952, 63). This radical theory was proposed first in 1977 in a book titled Peoples of the Sea, published by Jewish psychiatrist and independent scholar Immanuel Velikovsky (1895–1979)—the principal source for Down’s unconventional hypothesis.

Fig. 1. David Down’s revised Egyptian chronology [right column] (Ashton and Down 2006; Down 2010; 2011) compared with conventional Egyptian chronology [left column] (e.g., Shaw 2003).

Fig. #. “Genealogies of Rameses III and Nakhtnebef” with postulated equivalent identifications according to David Down (See Ashton and Down 2006, 180–181, 193, 210). Note that Rameses V, VII, and VIII have no identifiable equivalents.

Down confidently wrote this

Velikovsky, with good reason, identifies Rameses III with Nectenebo I of Dynasty 30 . . . long ago archaeologists assigned Rameses III to XI to Dynasty 20, but there was no valid reason for doing this and these pharaohs fit better into the Persian period (Ashton and Down 2006, 180–181).

In another publication he stated, “Rameses III was supposed to have ruled in the 12th century B.C., but . . . should be dated to the Persian period” (Down 2011, 89).

These claims (per Velikovsky) have significant implications—not merely for the historical setting of Rameses III’s reign, but also for the entire sequence of archaeological stratigraphy in the Near East—and can be tested using that same stratigraphic sequence.

Rameses III was a celebrated ruler, esteemed beyond the borders of his Nile kingdom. His cartouche (royal name ring) was displayed in foreign cities on door lintels, gateways, storage jars, amulets, and administrative seals. Over time, these inscriptions were lost beneath the accumulated rubble of sequential cities, one built on top of the other. These later cities were naturally younger (closer to the present) than the inscribed artifacts sealed beneath their foundations. In other words, a cartouche of Rameses III is older than any undisturbed (i.e., uncovered as originally deposited) sequence of debris sitting on top of it—for example, burn layers, wall foundations, or floor surfaces. This archaeological principle is called the law of superposition (Harris, 1989, 11–13, 30–31; Harris, Brown, and Brown 1993, 125, 154; Renfrew and Bahn 2000, 106; 2005, 181–182).

Consequently, if Down’s chronology is correct, sealed strata overlying objects with Rameses III’s name must date no earlier than the late Persian period, when Nakhtnebef lived. The terminus post quem (date after which) for these layers would be c. 380 BC. If these layers were deposited before the reign of Nakhtnebef, however, entombing artifacts of Rameses III beneath them, then Down’s particular revision of pharaonic history is flawed and systematically indefensible on the basis of archaeological stratigraphy (Renfrew and Bahn 2000, 118–119).

This paper will explore these implications using the well-documented sequence of stratigraphy uncovered at Tel Lachish—the cornerstone site for the archaeology of the Iron Age kingdom of Judah (Ussishkin 2004a, 92; 2014a, 389–390).

Tel Lachish

Tel Lachish (Tell ed-Duweir in Arabic) is an impressive mound-ruin approximately twentyfive miles southwest of Jerusalem, in the modern Southern District of Israel (see fig. 3). In 1929, the abandoned site was identified by renowned American archaeologist William Foxwell Albright as the location of biblical Lachish—the powerful fortress-city that once dominated the strategic lowland between the coastal plain and the Judean highlands (Ussishkin 2004a, 50–51; 2014a, 26). The summit of the mound, bounded by steep slopes, covers an area of eighteen acres (Ussishkin 1979, 16; 2014a, 22; 2014b, 76). It is one of the most significant archaeological remains from the biblical period (Ussishkin 2014a, 19).

Fig. 3. Location of Tel Lachish in modern Israel.

Excavations at Tel Lachish were inaugurated in 1932 under the direction of James Leslie Starkey (Ussishkin 1993, 897–898; 2014a, 9, 29–56; 2014b, 76), a former assistant of the legendary Egyptologist Flinders Petrie (1853–1942). Final reports from this expedition were published by Olga Tufnell in 1953 and 1958 (Ussishkin 2014a, 58). A smallscale investigation by Yohanan Aharoni in the late 1960s (Ussishkin 1993, 898; 2014a, 9, 60–64; 2014b, 76) was followed by a renewal of systematic excavations for the Institute of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University. David Ussishkin (1993, 898; 2004c, 17–21) directed these excavations from 1973 to 1987; he oversaw further fieldwork and reconstructions until 1994 (Ussishkin 2014a, 9). A fourth exploration of the site was launched in 2013 to clarify dates for the Iron IIA levels (Garfinkel, Hasel, and Klingbeil 2013). Seasonal excavations since 2017 have been coordinated under the auspices of the Hebrew University and the Austrian Academy of Sciences (Excavations 2020).

Nakhtnebef and the Persian Period—Lachish Level I (c. 450–150 BC)

When Kheperkare Nakhtnebef (Nectanebo I/Rameses III according to David Down) usurped the throne of Egypt in 379/8 BC (Grimal 1992, 375; Lloyd 2003, 377), more than six decades had elapsed since Nehemiah rebuilt the walls of Jerusalem (Douglas, Tenney, and Silva 2011, 1007–1010; Nehemiah 2:1–10; 6:15), and less than 50 years remained before young Alexander the Great would outfight the last Achaemenid king on the wide plain near Gaugamela (Bosworth 1994, 812–814; Hornblower 2002, 308–312; Ussher 2003, 234–236). This was during the Persian period in the Near East, a lengthy epoch of time corresponding to the era of Classical Greece (c. 510–323 BC).

During the Medo-Persian Empire (c. 550–330 BC), prior to the reign of Nakhtnebef in Egypt, Tel Lachish was re-occupied by Jews returning from the Babylonian Exile (Nehemiah 11:30). Archaeological remains from this city are preserved today in the top and final layer on the mound, identified by the excavators as Level I (phases A–B) (Ussishkin 1993, 910–911; 2014a, 391–401). Imported Attic fine ware, recovered in large quantities inside the provincial palace of Level I (the Residency), date this occupation phase to c. 450–350 BC (Stern 2001, 449), overlapping the reign of Nakhtnebef in Egypt (379–361 BC). Most of these imports were manufactured in Greece no earlier than c. 400 BC (Fantalkin and Tal 2004, 2187–2191; 2006, 167, 171–173). In contrast, a large Solar Shrine (Stern 2001, 479–480; Ussishkin 2014a, 402–407), constructed on the eastern side of the summit, contained later coins and vessels from the early Hellenistic period (Ussishkin 1993, 911; 2014a, 403), with some Hellenistic sherds recovered from pits beneath the floor (Fantalkin and Tal 2006, 176).2

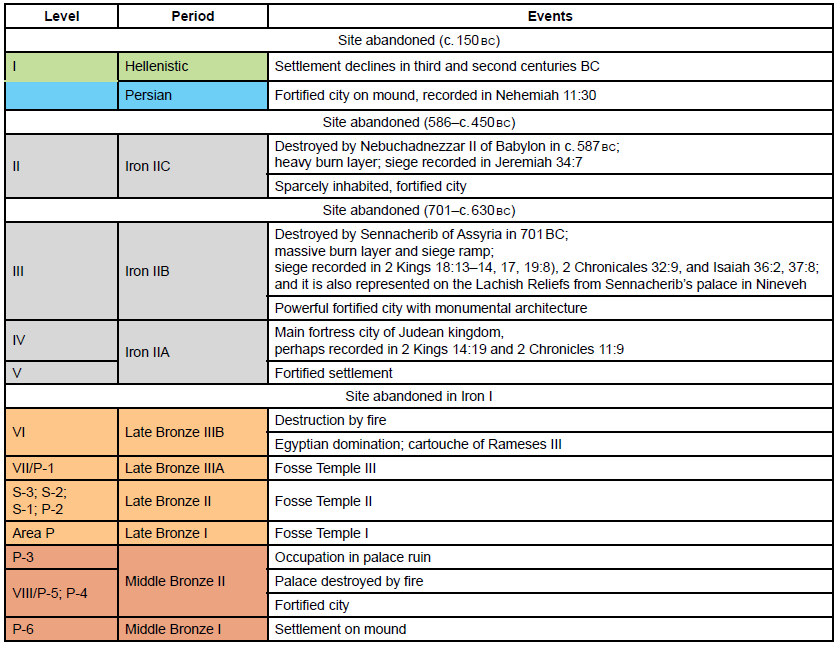

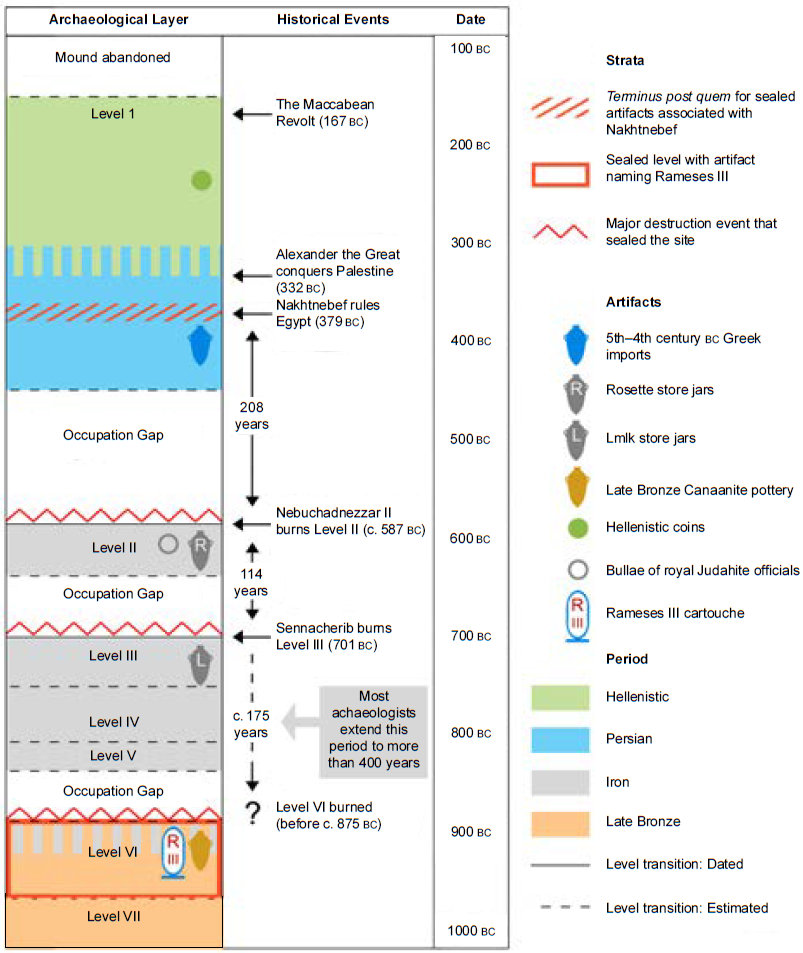

Earlier layers at Tel Lachish (Levels VIII–II), buried sequentially beneath Level I, predate the reign of Nakhtnebef by centuries (see table 1). For example, the city of Level II was burned by Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon more than two hundred years before Nakhtnebef lived (Ussishkin 1993, 909–910; 2014a, 375, 389, 415). Similarly, Sennacherib of Assyria comprehensively destroyed the powerful city of Level III in 701 BC (Ussishkin 1993, 907–909; 2014a, 219–221, 267–277, 389, 414–415). The Bible records the two sieges that resulted in these destructions (2 Chronicles 32:9; Jeremiah 34:7; 2 Kings 18:13–14, 17, 19:8; Isaiah 36:2, 37:8), and the rich archaeology at the site, corroborated by inscriptions of campaign and magnificent battle reliefs (Ussishkin 1977, 28–30; 1980; 2004a, 89–90; 2014a, 327–353), graphically elucidates the historic text (for a description of the Levels III–II destruction layers, see Appendix A).

Table 1. Stratigraphy of Tel Lachish (After Ussishkin 1993; 2004a; 2014a). Arranged from youngest to oldest layers (top to bottom), as found on the mound.

As a result, if Rameses III is the same person as Nakhtnebef, as Down claimed, stratified artifacts from his lifetime must be found above the sealed debris of the Babylonian destruction that ended Level II—a disastrous event that the Bible dates to c. 587 BC. In other words, these artifacts could be preserved only in the occupational layer of Level I, which lies directly below the surface of the mound. Is this what was found?

Finding Rameses III

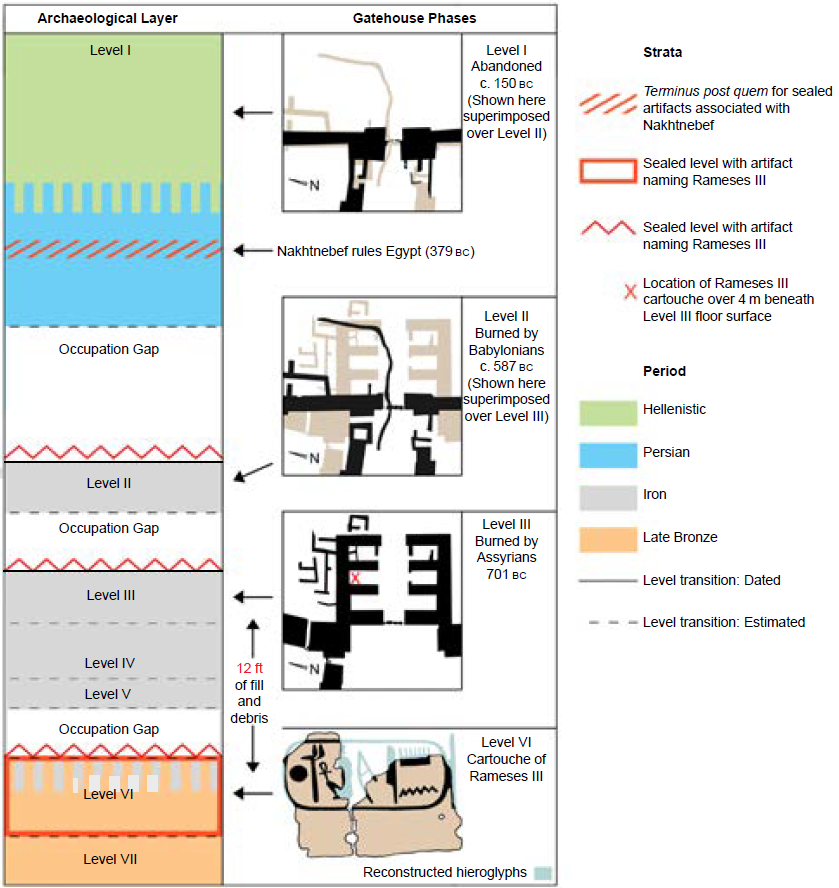

In 1978, a cache of bronze fragments was discovered sealed beneath the foundation of the inner gatehouse of Levels IV–III at Lachish (Locus 4164, Area GE), which was demolished by Sennacherib of Assyria over 300 years before Nakhtnebef was king (Ussishkin 2004a, 70). These fragments were overlaid by the massive Assyrian burn layer in Level III (Ussishkin 2014a, 219), the gatehouse foundation in Level IV, a lime-plastered surface in Level V (Locus 4159) and heavy destruction debris in Level VI (Ussishkin 1983, 120–123; 1985, 218–219; 1987, 34; 1993, 904; 2004b, 626–631, 682; 2014a, 194). The entire cache was entombed more than twelve feet (4 m.) beneath the surface of the Level-III floor (see fig. 4) (Ussishkin 1983, 122, Fig. 12; 2004b, 626, 629, Fig. 12.7, 682). One of these fragments, possibly part of a gate socket (King 2005, 39), was cast with the cartouche of an Egyptian pharaoh. This cartouche contained the praenomen (throne name) of Rameses III (A. Mazar 1992a, 299; Ussishkin 1983, 123–124, 168–169; 1993, 904; 2004b, 626).

Fig. 4. “Phases of Lachish gatehouse (Levels III-I)” Showing the location of the cartouche naming Rameses III (After Ussishkin 2004b; Ganor and Kreimerman 2019).

Describing this significant find, Ussishkin (2014a, 194) wrote the following:

The stratigraphic context of these bronzes is very clear: The foundations of the gatehouse were built over the layer of destruction debris of Level VI; the objects were found sealed beneath the destruction debris of that level. In other words, first the bronze objects were laid there and then they were buried under the debris from the destruction and the fire. This means that the bronzes are older than the destruction by fire of Level VI.

His quote continues,

We can therefore determine that Level VI was not destroyed before Rameses III ascended the throne and certainly sometime thereafter. All the bronze items, including the one bearing the royal cartouche, were broken or used; they would have been collected at the point where they were found in preparation for taking them away to be recast. This finding shows that a good deal of time would have passed between the time the item bearing the cartouche was cast and the time it was buried under the destruction debris of Level VI. (Ussishkin 2014a, 194)

Other finds at Tel Lachish align with Ussishkin’s conclusions. Starkey’s expedition, in the 1930s, recovered two scarabs from the same level (Area 7000 and Tomb 570), both incised with the cartouche of Usermaatre-Setpenamun Rameses IV,3 the son and successor of Rameses III (Lalkin 2004; Ussishkin 2004a, 70; 2007, 603; 2012, 195). Another scarab naming Rameses III was found in the construction fills beneath the monumental Iron Age Palace-Fort (Palace B) (Ussishkin 1985, 218, 220–221; 1993, 901–902; 2004a, 70, 104), which was occupied in Level IV (Ussishkin 2007, 603). The same fill-layer preserved Egyptian hieratic inscriptions on votive bowls that are believed to record regnal years of Rameses III (Goldwasser 1982; Mazar 1992a, 299; 1992b, 262; Ussishkin 1993, 904; 2014a, 188–190).

Level VI—The Timespan Between Rameses III and Nakhtnebef

A precise date for the violent conflagration that destroyed Level VI at Tel Lachish, sealing the cartouche of Rameses III beneath it, is not possible to determine (Ussishkin 2004a, 70–71). “Lacking inscriptions, we can only raise suppositions as to the identity of the enemy that conquered and destroyed the great and flourishing city” (Ussishkin 2014a, 196). Some scholars suggest an Israelite attack; others believe Lachish was burned by the Sea Peoples, or even the Egyptians (Ussishkin 1985, 223–224; 1993, 904; 2004a, 71–72). In any case, it is possible to estimate a minimum time frame for the destruction of Level VI by working backward through the archaeological sequence from the oldest absolute date at the site, which is 701 BC (Ussishkin 2014a, 389).

Level III: As noted above, King Sennacherib of Assyria (reigned 704–681 BC) comprehensively destroyed the fortified city of Lachish Level III—including the aforementioned inner gatehouse and Palace-Fort—during his third campaign in 701 BC (see Appendix A) (Luckenbill 1927, 118–121, 142–143, 154; Roux 1992, 320); he recorded this bloody triumph on gypsum panels at his self-styled “Palace Without Rival” in Nineveh, more than three centuries before Nakhtnebef lived (Layard 1853, 128; Luckenbill 1924, 94–101; 1927, 160–164; Ussishkin 1980; 2014a, 327–353). The year 701 BC, therefore, serves as a terminus ante quem (date before which) for all strata at Tel Lachish sealed beneath the thick Assyrian burn layer. This obviously includes the much deeper Level VI—the ruined city that entombed the artifacts of Rameses III and Rameses IV (see table 1).

Level IV: The Level IV city at Tel Lachish, which preceded Level III, may have come to an end prior to c. 750 BC, when the Bible describes a massive earthquake striking the region (Amos 1:1; Zechariah 14:5). Although seismic evidence at Lachish is elusive (Fantalkin and Finkelstein 2006, 22), possible earthquake damage at other Iron IIA/B sites in Israel, including Hazor, Arad, Tel Beersheba, Tell Deir Alla, Tell es-Safi, and Gezer (Austin 2010; Barkay 1992, 328; Finkelstein 1996, 183; Fantalkin and Finkelstein 2006, 22–23; Hergoz and Singer-Avitz 2004, 230; Maeir 2012a, 49–50), has led some scholars to identify this sudden upheaval as the terminus ante quem for the monumental buildings of Level IV (Ussishkin 1993, 907; 2014a, 214–215; 2015, 137). If this hypothesis is correct,4 and if a brief period of at least 50 years is assumed for the existence of Level IV at Tel Lachish before it was superseded, almost without interruption, by the construction phase of Level III, this would place its founding in the late ninth century BC.5

Level VI–V: The small, fortified (Garfinkel et al. 2019, 3–8) settlement of Level V, which stood on the mound prior to the construction of the monumental buildings in Level IV, cannot be dated with any precision (Kang 2016). However, pottery evidence seems to indicate that the city’s founding was preceded by a period when the site was completely abandoned. Ussishkin (2014a, 196, 202–203) estimates an occupation gap of two centuries between the construction of Level V and the earlier destruction of Level VI. Even if this gap was much shorter—again, say 50 years—it is reasonable to assume that the demolition of Level VI occurred before c. 875 BC. Of course, as with Level IV, it should be emphasized that this is a very low estimation; in other words, the end of Level VI could be older by decades or even centuries. For example, Ussishkin (1993, 904; 2014a, 194, 212; 2015, 134), following the traditional Egyptian timeline, dates this destruction to the late twelfth century BC (c. 1130 BC)—a conclusion bolstered by radiocarbon analysis (Garfinkel et al. 2019).

Either way, stratigraphy at Tel Lachish demonstrates that the fiery end of Level VI—and the cartouche of Rameses III beneath it—preceded the reign of Nakhtnebef by at least 500 years (see fig. 5). This effectively destroys any synchronism between Rameses III and Nakhtnebef and eliminates all theories associating their respective dynasties.

Fig. 5. Establishing a minimum estimate for the destruction of Level VI at Tel Lachish.

Correlations Between Tel Lachish and Other Ancient Sites

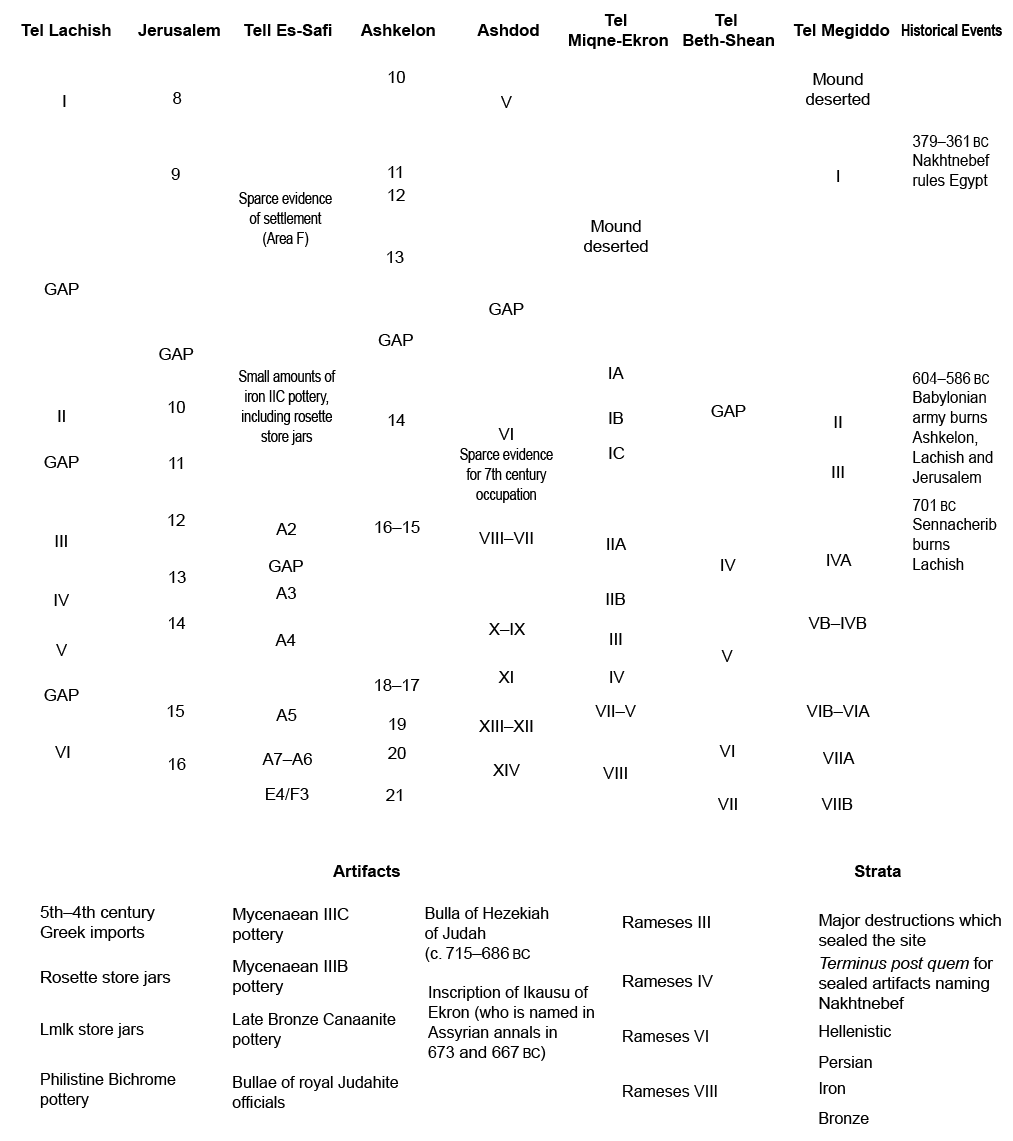

The stratigraphic sequence at Tel Lachish, so contrary to David Down’s theory, is mirrored at mound ruins across the Near East. In Level VI at Tel Lachish, objects naming Rameses III and Rameses IV were buried with fragments of Late Bronze (IIB/III) Canaanite-style pottery (Ussishkin 1983, 123; 2004b, 626). This pottery is preserved at many other sites in Israel intermixed with Iron I vessel fragments and Mycenaean (Monochrome) IIIC ware (Dothan 2000, 153; Killebrew 2000, 233). For example, Canaanite-style bowls, kraters, and storage jars, identical to Late Bronze pottery found in Level VI at Tel Lachish, also have been uncovered in Phase 20 (Grid 38) at Ashkelon, mingled with quantities of Mycenaean IIIC ware (Master, Stager, and Yasur-Landau 2011, 269–271, 277; Stager 2008). Significantly, Room 859 in the earliest deposits of Phase 20 at Ashkelon contained Mycenaean IIIC pottery and a scarab of Rameses III (Master, Stager, and Yasur-Landau 2011, 265, 274; Stager 2008; Stager, Master, and Schloen 2008, 258).

This pattern is repeated at Ashdod (Stratum XII) and Tel Beth-Shean (Strata VI/S4–S3) where artifacts incised with the cartouche of Rameses III (Brandl 2004, 59, 62, 64; Kitchen 1983, 252–253) have been unearthed in sealed contexts associated with Mycenaean IIIC ware and local Canaanite-style pottery manufactured in the early Iron I tradition (Dothan 1993, 96–98; Master, Stager, and Yasur-Landau 2011, 274–275; Mazar 1993b, 215–216, 228; 2007; 2008, 95; 2010, 255). Likewise, at Tel al-Mutessellim (Tel Megiddo), Iron I Canaanite-style pottery and Philistine vessels, including a single stirrup jar of the Mycenaean IIIC monochrome type (Finkelstein et al. 2017), surfaced in layers (Levels K-6, K-5/H–11, H–10) associated with destruction debris from Stratum VIIA (Finkelstein et al. 2017). This debris sealed an ivory pen case incised with the double cartouche of Rameses III (Kitchen 1983, 255), which was discovered in 1937 during excavations directed by Gordon Loud (Feldman 2009, 177; Finkelstein et al. 2017; Leonard and Cline 1998, 7–8; Loud 1939, 9, 11, Plate 62; 1948, 25; Mazar 1992a, 269, 299; 1992b, 261; Ussishkin 1995, 259). The same stratum at Megiddo is associated with a bronze statue base, found elsewhere on the mound (Room 1832, Area CC, Stratum VIIB), inscribed with the royal names of Nebmaatre-Meryamun Rameses VI—a younger son of Rameses III (Breasted 1948, 135–138; Finkelstein 2009, 115; Finkelstein et al. 2017, 262; Mazar 1992a, 299; 1992b, 261; Ussishkin 1995, 259–260).

All these inscriptions and pottery finds, like those at Tel Lachish, were discovered in layers predating the Persian period by multiple centuries (see fig. 6). For example, the above-mentioned scarab of Rameses III from Phase 20 (Period XVII) at Ashkelon was overlaid by a sequence of six Iron Age occupation levels (Grid 38, Phases 19–14)—each one constructed and demolished prior to the Persian period (Stager, Master, and Schloen 2008, 216–217, 257–282). In fact, the final Iron Age level in this sequence, Phase 14 (Period XII), was destroyed thoroughly by the Babylonian army more than two centuries before the reign of Nakhtnebef. This sudden destruction—foretold by the Prophet Jeremiah (Jeremiah 47:3–5)—took place in 604 BC when Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon sacked the city, deported its population, and turned the site into “heaps of ruins” (Fantalkin 2011; Stager, Master and Schloen 2008, 279–282; 2011, 3, 11, 13–14; Wiseman 1956, 28, 47, 69).

Fig. 6. “Stratigraphic correlations at sites in Palestine” Showing location of select artifacts, with particular emphasis on finds associated with Rameses III. Sources include the following: Arie 2006; 2013; Ariel et al. 2000; Barkay 1992; Dothan 1993; Dothan and Gitin 1993; Emanuel 2016; Finkelstein 2009; Finkelstein et al. 2017; Finkelstein and Singer-Avitz 2001; 2004; Gitin 1989; 2012; Leonard and Cline 1998; Maeir 2012a; 2012b; Master, Stager, and Yasur-Landau 2011; Mazar 1992a; 1992b; 1993a; 1993b; 2006; 2007; 2009a; 2015; Shai et al. 2004; Shiloh 1984; 1993a; 1993b; Singer-Avitz 2014; Stager, Master, and Schloen 2008; 2011; Stern 2001; Ussishkin 1993; 2004a; 2014a; 2015; Zukerman 2009; Zukerman, Dothan, and Gitin 2016.

Implications

Archaeological stratigraphy demonstrates that Rameses III lived no closer to present times than c. 875 BC. Stratified sequences of pottery, inscribed artifacts, and superimposed architecture at Tel Lachish and other ancient ruins in the Near East overwhelmingly refute David Down’s proposal to synchronize Rameses III with the Persian period (for corroborating evidence from Egypt, see Appendix B). The consequences of this refutation are devastating, not only for Down’s hypothesis regarding Rameses III, but also for the New Kingdom period of his revised Egyptian chronology.

Take, for example, Down’s attempt to harmonize the reign of Banenre Merneptah, fourth ruler of Dynasty 19, with the end of the biblical kingdom of Israel. On page 178 of Unwrapping the Pharaohs he wrote: “The fifth year of Merneptah would have been 722 B.C. or even later” (Ashton and Down 2006). Elsewhere in the same book (209), Down dated the first year of Merneptah to 693 BC—nearly a decade after the destruction of Lachish Level III by Sennacherib’s army.

Down’s scenario, however, is built on the premise that Merneptah lived before Rameses III. In this he agreed with the established sequence of New Kingdom pharaohs, accepted by all Egyptologists and confirmed by multiple pharaonic inscriptions (see Appendix C). For example, a relief at Medinet Habu shows Rameses III celebrating the Min Festival accompanied by a procession of former kings, which includes both Merneptah and his son Userkheperure Seti II (Dodson 2010, 129; Wilson and Allen 1940, Plates 196 [B], 203, 205, 207).

Consequently, because Merneptah lived prior to the reign of Rameses III, it is impossible to shift his lifetime after the destruction of Level VI at Tel Lachish that sealed the cartouche of Rameses III. In other words, like all kings who preceded Rameses III on the throne of the Two Lands (i.e., Upper and Lower Egypt), the beginning of Merneptah’s reign cannot be dated any closer to the present than sometime prior to c. 875 BC—a minimum of fifteen decades before Down’s proposed biblical correlation.6 This chronological dilemma is not an isolated example. Every correlation for the New Kingdom period of Egyptian history (Dynasties 18–20) identified by Down in Unwrapping the Pharaohs (108–181, 207–209—one-third of the book!) is challenged by the same stratigraphy that dates Rameses III’s reign prior to the mid ninth century BC.7 This includes Down’s central claim—another hypothesis conceived by Velikovsky (1952, 103–177)—that Maatkare Hatshepsut was Solomon’s “Queen of Sheba” (Ashton and Down 2006, 117, 121–122, 207, 213, 215; Down 2010, 29; 2011, 101, 106), and that Menkheperre Thutmose III was the plunderer of Solomon's Temple (Ashton and Down 2006, 125, 128–129, 207, 213, 215; Down 2010, 29; 2011, 109–110).

According to the Bible, Shishak plundered the Temple at Jerusalem in 926/5 BC (Kitchen 1996, 294–295; Thiele 1983, 80) within five years of Solomon’s death (1 Kings 14:25). Thutmose III, however, lived about 250 years before the reign of Rameses III (see Appendix D; both Thutmose III and Hatshepsut were separated from the time of Rameses III by approximately ten generations of reigning pharaohs). Consequently, if Thutmose III was ruling the Nile Valley in the late tenth century BC, as Down proposed, then Rameses III’s reign could date no further back in time than c. 675 BC—more than two decades after Sennacherib destroyed the Level III gatehouse at Lachish, whose deep Iron Age foundations (Levels V–IV) overlaid the earlier Bronze Age destruction layer (Level VI) that sealed the cartouche of Rameses III. The law of superposition makes such a scenario impossible; rather, it confirms that Thutmose III ruled Egypt sometime before 1100 BC,8 corroborating the significant body of evidence that makes Velikovsky’s link between Thutmose III and Shishak, or Hatshepsut and the Queen of Sheba, incompatible with the biblical evidence (Clarke 2010, 2011, 2013; Hornung, Krauss, and Warburton 2006, 15).

Conclusion

Despite endorsements in recent years by a small following of young-earth researchers (Austin 2012; Mitchell 2008; see Habermehl 2018 for a similar chronology), archaeological stratigraphy in the Near East strongly suggests that Down’s revision of Egypt's New Kingdom period of history is misaligned. At Tel Lachish, the gatehouse of Level III was burned by the Assyrians in 701 BC. The deep foundations beneath that gatehouse overlaid much earlier debris which sealed the cartouche of Rameses III. This stratigraphic sequence, paralleled by findings at ruins throughout Israel, contradicts any argument that dates Rameses III after the mid-ninth century BC. Consequently, if Rameses III is firmly entrenched in the pharaonic sequence before c. 875 BC, then every New Kingdom pharaoh who lived prior to his reign is centuries out-of-step with Down’s biblical correlations. When tested against the fundamental principles of archaeology, Down’s hypothesis struggles to explain archaeological finds throughout the Near East.9 Other alternatives should be explored that better fit the stratigraphic sequence.

References

Aharoni, Yohanan. 1993. “Ramat Raḥel.” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 4. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 1261–1267. Israel: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta, Jerusalem.

Albright, W. F. 1941. “The Lachish Letters after Five Years.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research No. 82 (Apr.): 18–24.

Arie, Eran. 2006. “The Iron Age I Pottery: Levels K-5 and K-4 and an Intra-site Spatial Analysis of the Pottery From Stratum VIA.” In Megiddo IV: The 1998–2002 Seasons, edited by Israel Finkelstein, David Ussishkin, and Baruch Halpern, 191–298. Monograph Series of the Institute of Tel Aviv University No. 24. Tel Aviv: The Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology. Arie, Eran. 2013. “The Late Bronze III and Iron I Pottery: Levels K-6, M-6, M-5, M-4 and H-9.” In Megiddo V: The 2004–2008 Seasons, Volume II, edited by Israel Finkelstein, David Ussishkin, and Eric H. Cline, 475–667. Monograph Series of the Institute of Tel Aviv University No. 24. Tel Aviv: The Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology.

Ariel, Donald T., Baruch Brandl, Jane M. Cahill, Joseph Naveh, and Yair Shoham. 2000. “Excavations at the City of David 1978–1985 Directed by Yigal Shiloh, Volume VI: Inscriptions.” Qedem 41. Monographs of the Institute of Archaeology: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Ashton, John, and David Down. 2006. Unwrapping the Pharaohs: How Egyptian Archaeology Confirms the Biblical Timeline. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Aston, David A. 2014. “Royal Burials at Thebes During the First Millennium BC.” In Thebes in the First Millenium BC, edited by Elena Pischikova, Julia Budka, and Kenneth Griffin, 15–59. Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Austin, David. 2012. “‘The Queen of the South’ is ‘the Queen of Egypt’.” Journal of Creation 26, no. 3 (December): 79–84. Austin, Steven A. 2010. “The Scientific and Scriptural Impact of Amos’ Earthquake.” Acts & Facts 39, no. 2 (February 1): 8–9.

Avi-Yonah, Michael. 1993. “Mareshah (Marisa).” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 3. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 948–951. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Ayad, Mariam F. 2009. “The Transition from Libyan to Nubian Rule: the Role of the God’s Wife of Amun.” In The Libyan Period in Egypt. Edited by G. P. F. Broekman, R. J. Demarée, and O. E. Kaper, 29–49. Historical and Cultural Studies into the 21st–24th Dynasties: Proceedings of a Conference at Leiden University, 25–27 October, 2007. The Netherlands Institute for the Near East, Volume 23. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten.

Ayad, Mariam F. 2016. “Reading a Chapel.” In “Prayer and Power”: Proceedings of the Conference on the God’s Wives of Amun in Egypt during the First Millennium BC. Edited by Meike Becker, Anke Ilona Blöbaum, and Angelika Lohwasser, 167–181. Ägypten und Altes Testament. Studien zu Geschichte, Kultur und Religion Ägyptens und des Alten Testaments Band 84. Münster, Germany: Ugarit-Verlag.

Barako, Tristan J. 2003. “The Changing Perception of the Sea Peoples Phenomenon: Migration, Invasion or Cultural Diffusion?” In ПɅОEƩ . . . Sea Routes . . . Interconnections in the Mediterranean 16th–6th c. BC. Proceedings of the International Symposium held at Rethymnon, Crete September 29th–October 2nd 2002. Edited by Nicholas Chr. Stampolidis and Vassos Karageorghis, 163–171. Athens, Greece: The University of Crete and the A.G. Leventis Foundation.

Barkay, Gabriel. 1992. “The Iron Age II–III.” In The Archaeology of Ancient Israel. Edited by Amnon Ben-Tor, 302–373. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Beckerath, Jürgen von. 1999. Handbuch der Ägyptischen Königsnamen. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien, Band 49. Münchner Universitätsschriften Philosophische Fakultät. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern.

Bosworth, A. B. 1994. “Alexander the Great Part I: The Events of the Reign.” In The Cambridge Ancient History. Volume VI: The Fourth Century B.C. 2nd ed. Edited by D. M. Lewis, John Boardman, Simon Hornblower, and M. Ostwald, 791–845. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Brand, Peter 1999. “Secondary Restorations in the Post-Amarna Period.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 36: 113–134.

Brand, Peter J. 2009. “Usurped Cartouches of Merenptah at Karnak and Luxor.” In Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane. Edited by Peter J. Brand and Louise Cooper, 29–48. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East, Vol. 37. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Brand, Peter J. 2010. “Reuse and Restoration.” In UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 1, no. 1: 1–13.

Brandl, Baruch. 2004. “Scarabs and Plaques bearing Royal Names of the Early 20th Egyptian Dynasty excavated in Canaan.” In Scarabs of the Second Millennium BC from Egypt, Nubia, Crete and the Levant: Chronological and Historical Implications. Edited by Manfred Bietak and

Ernst Czerny, 57–71. Papers of a Symposium, Vienna, 10th–13th of January 2002. Contributions to the Chronology of the Eastern Mediterranean, Volume VIII. Wien, Austria: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Breasted, James Henry. 1906a. Ancient Records of Egypt. Volume II: The Eighteenth Dynasty. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Breasted, James Henry. 1906b. Ancient Records of Egypt. Volume III. The Nineteenth Dynasty. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Breasted, James Henry. 1906c. Ancient Records of Egypt. Volume IV. The Twentieth to the Twenty-Sixth Dynasties. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Breasted, James Henry, ed. 1930. Medinet Habu. Volume I. Earlier Historical Records of Rameses III. Oriental Institute Publications 8. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Breasted, James Henry, ed. 1932. Medinet Habu—Volume II: Later Historical Records of Rameses III. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publication. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Breasted, James Henry. 1948. “Bronze Base of a Statue of Ramses VI Discovered at Megiddo.” In Megiddo II—Seasons of 1935–39. Text by Gordon Loud, 135–138. Oriental Institute Publications 62. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Bruyère, Bernard. 1930. “Mert seger à Deir el Médineh.” Memoires publiés par les membres de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale du Caire, 58. Cairo, Egypt: Imprimerie de l’institut français d’archéologie orientale.

Bruyère, Bernard. 1952. “Rapport sur les fouilles de Deir el Médineh: 1935–1940.” Fouilles de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, 20, no. 2. Cairo, Egypt: Imprimerie de l’institut français d’archéologie orientale.

Bryan, Betsy M. 1987. “Portrait Sculpture of Thutmose IV.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 24: 3–20.

Bryan, Betsy M. 2012. “Episodes of Iconoclasm in the Egyptian New Kingdom.” In Iconoclasm and Text Destruction in the Ancient Near East and Beyond. Edited by Natalie Naomi May. Oriental Institute Seminars, No. 8. Chicago, Illinois: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Bryce, Trevor. 1998. The Kingdom of the Hittites. New York, New York: Oxford University Press Inc.

Bunimovitz, Shlomo, and Zvi Lederman. 1993. “Beth-Shemesh.” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 1. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 249–253. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Cahill, Jane M. 1995. “Rosette Stamp Seal Impressions from Ancient Judah.” Israel Exploration Journal 45, no. 4: 230–252.

Cahill, Jane M. 1997. “Royal Rosettes: Fit for a King.” Biblical Archaeology Review 23, no. 5 (September/October): 48–49, 51, 56–57, 68.

Callender, Vivienne G. 2004. “Queen Tausret and the End of Dynasty 19.” Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 32: 81–104.

Černý, Jaroslav. 1958. “A Hieroglyphic Ostracon in the Museum of Fine Arts at Boston.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 44 (December): 23–25.

Clarke, Patrick. 2010. “Why Pharaoh Hatshepsut is not to be equated to the Queen of Sheba.” Journal of Creation 24, no. 2 (August): 62–68.

Clarke, Patrick. 2011. “Was Thutmose III the Biblical Shishak?—Claims for the ‘Jerusalem’ Bas-Relief at Karnak Investigated.” Journal of Creation 25, no. 1 (April): 48–56.

Clarke, Patrick. 2013. “The Queen of Sheba and the Ethiopian problem.” Journal of Creation 27, no. 2 (August): 55–61.

Clayton, Peter A. 1994. Chronicle of the Pharaohs. New York, New York: Thames and Hudson.

Cline, Eric H. and David O’Connor. 2006. Thutmose III: A New Biography. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

Cline, Eric H. and David O’Connor. 2012. “The Sea Peoples.” In Ramesses III: The Life and Times of Egypt’s Last Hero. Edited by Eric H. Cline and David O’Connor, 180–208. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

Cook, J. M. 1983. The Persian Empire. London, United Kingdom: The Orion Publishing Group Ltd.

Corsi, Alessio. 2013. “The Songstress Diesehebsed in the ‘Chapel of Osiris-Onnophris in the Persea Tree’ in Karnak.” In SOMA 2012. Identity and Connectivity: Proceedings of the 16th Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology, Florence, Italy, 1–3 March 2012. Volume 1. Edited by Luca Bombardieri, Anacleto D’Agostino, Guido Guarducci, Valentina Orsi, and Stefano Valentini, 537–543. BAR International Series 2581 (I). Oxford, England: Archaeopress.

Coulon, Laurent, Alexsandra Hallmann, and Frédéric Payraudeau. 2018. “The Osirian Chapels at Karnak: An Historical and Art Historical Overview Based on Recent Fieldwork and Studies.” In Thebes in the First Millennium BC: Art and Archaeology of the Kushite Period and Beyond. Edited by Elena Pischikova, Julia Budka, and Kenneth Griffin, 271–293. London, United Kingdom: Golden House Publications.

Creasman, Pearce Paul, W. Raymond Johnson, J. Brett McClain, and Richard H. Wilkinson. 2014. “Foundation or Completion? The Status of Pharaoh-Queen Tausret’s Temple of Millions of Years.” Near Eastern Archaeology 77, no. 4 (December): 274–283.

Cross, Stephen W. 2008. “The Restoration Graffiti in the Tomb of Tuthmosis IV, KV43.” The Heritage of Egypt 1, no. 3, issue 3 (September): 9–11.

Davies, W. V. 2014. “A View From Elkab: The Tomb and Statues of Ahmose-Pennekhbet.” In Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut. Edited by José M. Galán, Betsy M. Bryan, and Peter F. Dorman, 381–409. Papers from the Theban Workshop 2010. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, No. 69. Chicago, Illinois: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

de Garis Davies, Norman. 1908. The Rock Tombs of El Amarna. Part VI. Tombs of Parennefer, Tutu, and Aÿ. Archaeological Survey of Egypt 18. Edited by F. L. L. Griffith. London, United Kingdom: The Egypt Exploration Society.

Deutsch, Robert. 2002. “Lasting Impressions.” Biblical Archaeology Review 28, no. 4 (July/August): 42–46, 49–51, 60–61.

Deutsch, Robert. 2009. “Tracking Down Shebnayahu, Servant of the King.” Biblical Archaeology Review 35, no. 3 (May/ June): 45–49.

Diodorus Siculus. 1952. Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, Volume VII: Books 15.20–16.65. Translated by Charles L. Sherman. The Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Dodson, Aidan. 1999. “The Decorative Phases of the Tomb of Sethos II and Their Historical Implications.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 85, no. 1 (December): 131–142.

Dodson, Aidan. 2009. Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation. Cairo, Egypt: The American University of Cairo Press.

Dodson, Aidan M. 2010. Poisoned Legacy: The Fall of the Nineteenth Egyptian Dynasty. Cairo, Egypt: The American University in Cairo Press.

Dodson, Aidan. 2011. “Fade to Grey: The Chancellor Bay, Éminence Grise of the Late Nineteenth Dynasty.” In Ramesside Studies in Honour of K. A. Kitchen. Edited by Mark Collier and Steven R. Snape, 145–158. Bolton, United Kingdom: Rutherford Press.

Dodson, Aidan. 2012. Afterglow of Empire: Egypt from the Fall of the New Kingdom to the Saite Renaissance. Cairo, Egypt: The American University of Cairo Press.

Dodson, Aidan. 2016. Amarna Sunrise: Egypt from Golden Age to Age of Heresy. Cairo, Egypt: The American University of Cairo Press.

Dodson, Aidan, and Dyan Hilton. 2004. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London, United Kingdom: Thames and Hudson.

Dodson, Aidan, and Salima Ikram. 2008. The Tomb in Ancient Egypt. London, United Kingdom: Thames and Hudson.

Dothan, Moshe. 1993. “Ashdod.” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 1. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 93–102. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Dothan, Trude. 2000. “Reflections on the Initial Phase of Philistine Settlement.” In The Sea Peoples and Their World: A Reassessment, edited by Eliezer D. Oren, 145–158. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Dothan, Trude, and Seymour Gitin. 1993. “Tel Miqne (Ekron).” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 3. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 1051–1059. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Douglas, J. D., Merrill C. Tenney, and Moisés Silva. 2011. Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

Down, David. 2010. The Archaeology Book. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Down, David. 2011. Unveiling the Kings of Israel. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Edgerton, William F. 1933. The Thutmosid Succession. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, 8. Edited by James Henry Breasted. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Eisenlohr, A. 1881. “An Historical Monument.” In Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology. Eleventh Session, 1880–1881: 97–102.

Emanuel, Jeffrey P. 2016. “‘Dagon Our God’: Iron I Philistine Cult in Text and Archaeology.” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions 16, no. 1 (June): 22–66.

Epigraphic Survey, The. 1936. Reliefs and Inscriptions at Karnak, Volume II. Ramses III’s Temple Within the Great Inclosure of Amon, Part II; and Ramses III’s Temple in the Precinct of Mut. Plates 79–125. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications, Vol. 35. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Epigraphic Survey, The. 1954. Reliefs and Inscriptions at Karnak, Volume III. The Bubastite Portal. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications, Vol. 74. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Epigraphic Survey, The. 1964. Medinet Habu, Vol. VII: The Temple Proper, Pt. III: The Third Hypostyle Hall and All Rooms Accessible from It, with Friezes of Scenes from the Roof Terraces and Exterior Walls of the Temple. Plates 483–590. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications, Vol. 93. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Excavations, Tel Lachish. 2020. “Tracing Transformations in the Southern Levant: From Collapse to Consolidation in the Mid-Second Millennium BC.” 2017–2020. https:// tracingtransformations.com/tel-lachish-excavations/

Fairman, H. W. 1939. “Preliminary Report on the Excavations at ‘Amāra West, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1938–9.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 25 (June 1): 139–144. London, United Kingdom: The Egypt Exploration Society.

Fantalkin, Alexander. 2011. “Why Did Nebuchadnezzar II Destroy Ashkelon in Kislev 604 B.C.E.?” In The Fire Signals of Lachish: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Israel in the Late Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Persian Period in Honor of David Ussishkin. Edited by Israel Finkelstein and Nadav Na’aman, 87–111. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns Inc.

Fantalkin, Alexander, and Israel Finkelstein. 2006. “The Shoshenq I Campaign and the 8th-Century BCE Earthquake—More on the Archaeology and History of the South in the Iron I–IIa.” Tel Aviv 33, no. 1 (February): 18–42.

Fantalkin, Alexander, and Oren Tal. 2004. “The Persian and Hellenistic Pottery of Level I.” In The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish—1973–1994, Vol. 4. Edited by David Ussishkin, 2174–2194. Tel Aviv University Monograph Series 22. Tel Aviv.

Fantalkin, Alexander, and Oren Tal. 2006. “Redating Lachish Level I: Identifying Achaemenid Imperial Policy at the Southern Frontier of the Fifth Satrapy.” In Judah and the Judeans in the Persian Period. Edited by Oded Lipschits and Manfred Oeming, 167–197. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Feldman, Marian H. 2009. “Hoarded Treasures: The Megiddo Ivories and the End of the Bronze Age.” Levant 41, no. 2 (29 November): 175–194.

Finkelstein, Israel. 1996. “The Archaeology of the United Monarchy: An Alternative View.” Levant 28, no. 1 (18 July): 177–187.

Finkelstein, Israel. 2009. “Destructions: Megiddo as a Case Study.” In Exploring the Longue Durée, Essays in Honor of Lawrence E. Stager. Edited by J. David Schloen, 113–126. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Finkelstein, Israel, Eran Arie, Mario A. S. Martin, and Eli Piasetzky. 2017. “New Evidence on the Late Bronze/Iron I Transition at Megiddo: Implications for the End of the Egyptian Rule and the Appearance of Philistine Pottery.” Ägypten und Levante/Egypt and the Levant 27: 261–280.

Finkelstein, Israel, and Lily Singer-Avitz. 2001. “Ashdod Revisited.” Tel Aviv 28, no. 2: 231–259.

Finkelstein, Israel, and Lily Singer-Avitz. 2004. “‘Ashdod Revisited’—Maintained.” Tel Aviv 31, no. 1: 122–135.

Ganor, Saar, and Igor Kreimerman. 2017. “Going to the Bathroom at Lachish.” Biblical Archaeology Review, 43, no. 6 (November): 56–60.

Ganor, Saar, and Igor Kreimerman. 2019. “An Eighth Century B.C.E. Gate Shrine at Tel Lachish, Israel.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 381 (May): 211–236.

Gardiner, Alan. 1958. “Only One King Siptaḥ and Twosre Not His Wife.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 44 (December): 12–22.

Gardiner, Alan. 1961. Egypt of the Pharaohs: An Introduction. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Garfinkel, Yosef, Michael G. Hasel, and Martin G. Klingbeil. 2013. “An Ending and a Beginning.” Biblical Archaeology Review 39, no. 6 (November/December): 44–51.

Garfinkel, Yosef, Michael G. Hasel, Martin G. Klingbeil, Hoo-Goo Kang, Gwanghyun Choi, Sang-Yeup Chang, Soonhwa Hong, Saar Ganor, Igor Kreimerman, and Christopher Bronk Ramsey. 2019. “Lachish Fortifications and State Formation in the Biblical Kingdom of Judah in Light of Radiometric Datings.” Radiocarbon 61, no. 3 (June): 695–712.

Gautschy, Rita. 2014. “A Reassessment of the Absolute Chronology of the Egyptian New Kingdom and Its ‘Brotherly’ Countries.” Ägypten und Levante/Egypt and the Levant 24: 141–158.

Gitin, Seymour. 1989. “Tel Miqne-Ekron: A Type-Site for the Inner Coastal Plain in the Iron Age II Period.” In Recent Excavations in Israel: Studies in Iron Age Archaeology. Edited by Seymour Gitin and William G. Dever, 15–58. The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research, Vol. 49. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Gitin, Seymour. 2012. “Temple Complex 650 at Ekron: The Impact of Multi-Cultural Influences on Philistine Cult in the Late Iron Age.” In Temple Building and Temple Cult: Architecture and Cultic Paraphernalia of Temples in the Levant (2.–1. Mill. B.C.E.). Edited by Jens Kamlah, 223–256. Abhandlungen des Palästina-Vereins, Vol. 41. Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Goldwasser, Orly. 1982. “The Lachish Hieratic Bowl Once Again.” Tel Aviv 9, no. 2: 137–138.

Gottlieb, Yulia. 2004. “The Weaponry of the Assyrian Attack Section A: The Arrowheads and Selected Aspects of the Siege Battle.” In The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994). Vol. 4. Edited by David Ussishkin et al., 1907–1969. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University No. 22.

Grandet, Pierre. 2014. “Early-mid 20th Dynasty.” In UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Edited by Wolfram Grajetzki and Willeke Wendrich. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/ viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002j95tk.

Greenberg, Raphael. 1993. “Tell Beit Mirsim.” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 1. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 177–180. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Grimal, Nicolas. 1992. A History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishers.

Habermehl, Anne. 2018. “Chronology and the Gezer Connection—Solomon, Thutmose III, Shishak and

Hatshepsut.” Journal of Creation 32, no. 2 (August): 83–90. Haider, Peter W. 2012. “The Aegean and Anatolia.” In Ramesses III: The Life and Times of Egypt’s Last Hero. Edited by Eric H. Cline and David O’Connor, 151–160. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

Harris, Edward. 1989. Principles of Archaeological Stratigraphy. 2nd ed. San Diego, California: Academic Press Limited.

Harris, Edward C., Marley R. Brown III, and Gregory J. Brown, eds. 1993. Practices of Archaeological Stratigraphy. San Diego, California: Academic Press Limited.

Hergoz, Ze’ev. 1993. “Tel Beersheba.” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 1. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 167–173. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Hergoz, Ze’ev, and Lily Singer-Avitz. 2004. “Redefining the Centre: The Emergence of State in Judah.” Tel Aviv 31, no. 2: 209–244.

Hölscher, Uvo. 1934. General Plans and Views. The Excavation of Medinet Habu. Vol. 1. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications. Vol. 21. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Hölscher, Uvo. 1939. The Temples of the Eighteenth Dynasty. The Excavation of Medinet Habu, Vol. 2. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications. Vol. 41. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Hölscher, Uvo. 1941. The Mortuary Temple of Ramses III, Part 1. The Excavation of Medinet Habu. Vol. 3. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications. Vol. 54. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Hölscher, Uvo. 1951. The Mortuary Temple of Ramses III, Part 2. The Excavation of Medinet Habu. Vol. 4. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications. Vol. 55. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Hölscher, Uvo. 1954. Post-Ramessid Remains: The Excavation of Medinet Habu. Vol. 5. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications. Vol. 66. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Hornblower, Simon. 2002. The Greek World 479–323 BC. 4th ed. New York, New York: Routledge. Hornung, Erik, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton, eds. 2006. Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1. The Near and Middle East. Vol. 83. Edited by W. H. van Soldt. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

James, T. G. H. 1963. “Editorial Foreword.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 49 (December): 1–4.

Kang, Hoo-Goo. 2016. “Four Notes on Tel Lachish Level V.” In From Shaʻar Hagolan to Shaaraim. Essays in Honor of Prof. Yosef Garfinkel. Edited by Saar Ganor, Igor Kreimerman, Katharina Streit, and Madeleine Mumcuoglu, 283–294. Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Exploration Society.

Killebrew, Ann E. 2000. “Aegean-Style Early Philistine Pottery in Canaan During the Iron I Age: A Stylistic Analysis of Mycenaean IIIC:Ib Pottery and Its Associated Wares.” In The Sea Peoples and Their World: A Reassessment. Edited by Eliezer D. Oren, 233–255. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

King, Philip J. 2005. “Why Lachish Matters.” Biblical Archaeology Review 31, no. 4 (July/August): 36–47.

Kitchen, K. A. 1972. “Ramesses VII and the Twentieth Dynasty.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 58 (August): 182–194.

Kitchen, K. A. 1982. “The Twentieth Dynasty Revisited.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 68 (August): 116–125.

Kitchen, K. A. 1983. Ramesside Inscriptions: Historical and Biographical. Vol. 5. Oxford, United Kingdom: B. H. Blackwell.

Kitchen, K. A. 1996. The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxbow Books.

Kitchen, K. A. 2012. “Ramesses III and the Ramesside Period.” In Ramesses III: The Life and Times of Egypt’s Last Hero. Edited by Eric H. Cline and David O’Connor, 1–26. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

Lalkin, Nir. 2004. “A Rameses IV Scarab from Lachish.” Tel Aviv 31, no. 1: 15–19.

Layard, Austen H. 1853. Discoveries Among the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. New York, New York: Harper and Brothers.

Leonard, Albert Jr., and Eric H. Cline. 1998. “The Aegean Pottery at Megiddo: An Appraisal and Reanalysis.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 309 (February): 3–39.

Leprohon, Ronald J. 2013. The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary. Writings from the Ancient World, 29. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature.

Li, Jean. 2011. “The Singers in the Residence of the Temple of Amen at Medinet Habu: Mortuary Practices, Agency, and the Material Constructions of Identity.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 47: 217–230.

Lloyd, Alan B. 1994. “Egypt, 404–332 B.C.” In The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 6. The Fourth Century B.C. 2nd ed. Edited by D. M. Lewis, John Boardman, Simon Hornblower, and M. Ostwald, 337–360. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Lloyd, Alan B. 2003. “The Late Period (664–332 BC).” In The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, edited by Ian Shaw, 364–387. New York: Oxford University Press Inc.

Loud, Gordon. 1939. The Megiddo Ivories. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications. Vol. 52. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Loud, Gordon. 1948. Megiddo 2: Seasons of 1935–39: Text. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications. Vol. 62. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Luckenbill, Daniel David. 1924. The Annals of Sennacherib. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications. Vol. 2. Edited by James Henry Breasted. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Luckenbill, Daniel David. 1927. Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia. Vol. 2. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Maeir, Aren M. ed. 2012a. Tell es-Safi/Gath I: The 1996-2005 Seasons. Part 1. Text. Studien zu Geschichte, Kultur und Religion Ägyptens und des Alten Testaments. Herausgegeben von Manfred Görg. Band 69. Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Maeir, Aren M. ed. 2012b. Tell es-Safi/Gath I: The 1996-2005 Seasons—Part 2: Plates. Studien zu Geschichte, Kultur und Religion Ägyptens und des Alten Testaments. Herausgegeben von Manfred Görg. Band 69. Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Manley, Bill. 1996. The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Egypt. New York, New York: Penguin Putnam.

Manuelian, Peter der, and Christian E. Loeben. 1993. “New Light on the Recarved Sarcophagus of Hatshepsut and Thutmose I in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 79: 121–155.

Mariette, Auguste. 1857. Le Sérapéum de Memphis. Paris, France: Gide, Libraire-Éditeur.

Master, Daniel M., Lawrence E. Stager, and Assaf Yasur-Landau. 2011. “Chronological Observations at the Dawn of the Iron Age in Ashkelon.” Ägypten und Levante/Egypt and the Levant 21: 261–280.

Mazar, Amihai. 1992a. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000–586 B.C.E. The Anchor Bible Reference Library. New York, New York: Doubleday.

Mazar, Amihai. 1992b. “The Iron Age I.” In The Archaeology of Ancient Israel. Edited by Amnon Ben-Tor, 258–301. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

Mazar, Amihai. 1993a. “Beth-Shean: Tel Beth-Shean and the Northern Cemetery.” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 1. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 214–223. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Mazar, Amihai. 1993b. “Beth Shean in the Iron Age: Preliminary Report and Conclusions of the 1990–1991 Excavations.” Israel Exploration Journal 43, no. 4: 201–229.

Mazar, Amihai. 2006. Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean 1989–1996. Vol. 1. From the Late Bronze Age IIB to the Medieval Period. Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Exploration Society and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Mazar, Amihai. 2007. “Myc IIIC in the Land of Israel: Its Distribution, Date and Significance.” In The Synchronisation of Civilisations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. III. Edited by Manfred Bietak and Ernst Czerny, 571–582. Proceedings of the SCIEM 2000—2nd EuroConference Vienna, 28th of May—1st of June 2003. Contributions to the Chronology of the Eastern Mediterranean. Vol. 9. Wien, Germany: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Mazar, Amihai. 2008. “From 1200 to 850 B.C.E.: Remarks on Some Selected Archaeological Issues.” In Israel in Transition: From Late Bronze II to Iron IIA (c. 1250–850 B.C.E.). Edited by Lester L. Grabbe, 86–120. New York, New York: T & T Clark International.

Mazar, Amihai. 2009a. “Introduction and Overview.” In Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean 1989–1996. Vol. 3. The 13th–11th Century BCE Strata in Areas N and S. Edited by Nava Panitz-Cohen and Amihai Mazar, 1–32. The Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Jerusalem, Israel: The Israel Exploration Society.

Mazar, Amihai. 2010. “Tel Beth-Shean: History and Archaeology.” In One God–One Cult–One Nation. In Archaeological and Biblical Perspectives. Edited by Reinhard G. Kratz and Hermann Spieckermann, 239–271. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift fur die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 405, Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

Mazar, Amihai, and George L. Kelm. 1993. “Tel Batash (Timnah).” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 1. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 152–157. Jerusalem, Israel: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Mazar, Benjamin. 1993c. “En-Gedi.” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 2. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 399–405. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Mazar, Eilat. 2009b. “The Wall That Nehemiah Built.” Biblical Archaeology Review 35, no. 2 (March/April): 24–28, 30–33, 66.

Mazar, Eilat. 2015. “A Seal Impression of King Hezekiah from the Ophel Excavations.” In The Ophel Excavations to the South of the Temple Mount 2009–2013: Final Reports. Vol. 1. Edited by Eilat Mazar, 629–640. Israel, Jerusalem: Old City Press.

Mitchell, Elizabeth. 2008. “Doesn’t Egyptian Chronology Prove That the Bible Is Unreliable?” In The New Answers Book 2. Edited by Ken Ham, 245–263. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Morkot, Robert G. 2013. “From Conquered to Conqueror: The Organization of Nubia in the New Kingdom and the Kushite Administration of Egypt.” In Ancient Egyptian Administration. Edited by Juan Carlos Moreno García, 911–963. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

Morkot, Robert G. 2016. “The Late-Libyan and Kushite God’s Wives. Historical and Art-historical Questions.” In “Prayer and Power”: Proceedings of the Conference on the God’s Wives of Amun in Egypt during the First Millennium BC. Edited by Meike Becker, Anke Ilona Blöbaum, and Angelika Lohwasser, 107–119. Ägypten und Altes Testament. Studien zu Geschichte, Kultur und Religion Ägyptens und des Alten Testaments. Band 84. Münster, Germany: Ugarit-Verlag.

Mykytiuk, Lawrence J. 2004. Identifying Biblical Persons in Northwest Semitic Inscriptions of 1200–539 B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature. No. 12. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

O’Connor, David. 2000. “The Sea Peoples and the Egyptian Sources.” In The Sea Peoples and Their World: A Reassessment. Edited by Eliezer D. Oren, 85–102. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

O’Connor, David. 2012. “The Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu.” In Ramesses III: The Life and Times of Egypt’s Last Hero. Edited by Eric H. Cline and David

O’Connor, 209–270. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

Peden, Alexander J.. 2001. The Graffiti of Pharaonic Egypt: Scope and Roles of Informal Writing (c. 3100–332 B.C.). Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

Perdu, Olivier. 2010. “Saites and Persians (664–332).” In A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Vol. I. Edited by Alan B. Lloyd, 140–158. Chichester, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Piepkorn, Arthur Carl. 1933. Historical Prism Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal I. Editions E, B1–5, D, and K. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago Assyriological Studies. No. 5. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Polz, Daniel. 1998. “The Ramsesnakht Dynasty and the Fall of the New Kingdom: A New Monument in Thebes.” Studien zur Altägypyischen Kultur, 25: 257–293.

Porter, Bertha, and Rosalind L. B. Moss. 1952. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings. Vol. 7. Nubia, the Deserts, and Outside Egypt. Oxford, United Kingdom: Griffith Institute.

Pritchard, James. ed. 1969. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. 3rd ed. with supplement. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Randall-MacIver, D., and C. Leonard Woolley. 1911a. Buhen: Plates. The Eckley B. Coxe Junior Expedition to Nubia. Vol. 8. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The University Museum.

Randall-MacIver, D., and C. Leonard Woolley. 1911b. Buhen: Text. The Eckley B. Coxe Junior Expedition to Nubia. Vol. 8. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The University Museum.

Redford, Donald B. 2000. “Egypt and Western Asia in the Late New Kingdom: An Overview.” In The Sea Peoples and Their World: A Reassessment. Edited by Eliezer D. Oren, 1–20. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Redford, Donald B. 2003. The Wars in Syria and Palestine of Thutmose III. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 16. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

Reeves, Nicholas, and Richard H. Wilkinson. 1996. The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt’s Greatest Pharaohs. London, United Kingdom: Thames and Hudson.

Renfrew, Colin, and Paul Bahn. 2000. Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice. 3rd ed. London, United Kingdom: Thames and Hudson.

Renfrew, Colin, and Paul Bahn. eds. 2005. Archaeology: The Key Concepts. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Rohl, David. 1995. A Test of Time: The Bible—From Myth to History. London, United Kingdom: Century.

Roux, Georges. 1992. Ancient Iraq. 3rd ed. London, England: Penguin.

Schneider, Thomas. 2010. “Contributions to the Chronology of the New Kingdom and the Third Intermediate Period.” Ägypten und Levante/Egypt and the Levant 20: 373–403. Schneider, Tsvi. 1991. “Six Biblical Signatures.” Biblical Archaeology Review 17, no. 4 (July/August): 26–28, 30–33.

Shai, Itzhaq, Aren M. Maeir, and David Ben-Shlomo. 2004. “Late Philistine Decorated Ware (“Ashdod Ware”): Typology, Chronology, and Production Centers.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 335 (August): 1–36.

Shaw, Ian, ed. 2003. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press Inc.

Shiloh, Yigal. 1984. “Excavations at the City of David I, 1978–1982: Interim Report of the First Five Seasons.” Qedem 19: I–XII, 1–72. Monographs of the Institute of Archaeology. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Shiloh, Yigal. 1993a. “Jerusalem.” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 2. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 701–712. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Shiloh, Yigal. 1993b. “Megiddo.” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 3. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 1003–1023. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Singer-Avitz, Lily. 2014. “The Pottery of Megiddo Strata III-II and a Proposed Subdivision of the Iron IIC Period in Northern Israel.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 372 (November): 123–145.

Stager, Lawrence E. 2008. “Tel Ashkelon.” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 5. Supplementary volume. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 1578–1586. Jerusalem, Israel: The Israel Exploration Society.

Stager, Lawrence E., Daniel M. Master, and J. David Schloen. 2008. Ashkelon 1: Introduction and Overview (1985–2006). Final Reports of the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon. Harvard Semitic Publications. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Stager, Lawrence E., Daniel M. Master, and J. David Schloen. 2011. Ashkelon 3: The Seventh Century B.C. Final Reports of the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon. Harvard Semitic Publications. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Stern, Ephraim. 2001. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, Volume II. The Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian Periods 732–332 B.C.E. The Anchor Bible Reference Library. New York, New York: Doubleday.

Stern, Ephraim. 2014. “The Other “Philistines”.” Biblical Archaeology Review 40, no. 6 (November/December): 30–40.

Thiele, Edwin R. 1983. The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications.

Thijs, Ad. 2004. “‘My Father Was Buried During Your Reign’: The Burial of the High Priest Ramessesnakht under Ramses XI.” Discussions in Egyptology 60: 87–95.

Ussher, James. 2003. The Annals of the World. Translated by Larry Pierce and Marion Pierce. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Ussishkin, David. 1976. “Royal Judean Storage Jars and Private Seal Impressions.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 223 (October): 1–13.

Ussishkin, David. 1977. “The Destruction of Lachish by Sennacherib and the Dating of the Royal Judean Storage Jars.” Tel Aviv 4, nos. 1–2: 28-60.

Ussishkin, David. 1979. “Answers at Lachish.” Biblical Archaeology Review 5, no. 6 (November/December): 16–38.

Ussishkin, David. 1980. “The ‘Lachish Reliefs’ and the City of Lachish.” Israel Exploration Journal 30 (3–4): 174–195.

Ussishkin, David. 1983. “Excavations at Tel Lachish 1978–1983: Second Preliminary Report.” Tel Aviv 10, no. 2: 97–175.

Ussishkin, David. 1984. “News from the Field: Defensive Judean Counter-Ramp Found at Lachish in 1983 Season.” Biblical Archaeology Review 10, no. 2 (March–April): 66–73.

Ussishkin, David. 1985. “Levels VII and VI at Tel Lachish and the End of the Late Bronze Age in Canaan.” In Palestine in the Bronze and Iron Ages: Papers in Honour of Olga Tufnell. Edited by Jonathan N. Tubb, 213–230. London, United Kingdom: Institute of Archaeology.

Ussishkin, David. 1987. “Lachish—Key to the Israelite Conquest of Canaan?” Biblical Archaeology Review 13, no. 1 (January/February): 18, 20–23, 28–29, 31, 34–39.

Ussishkin, David. 1990. “The Assyrian Attack on Lachish: The Archaeological Evidence From the Southwest Corner of the Site.” Tel Aviv 17, no. 1: 53–86.__

Ussishkin, David. 1993. “Lachish.” In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 3. Edited by Ephraim Stern, 897–911. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society and Carta.

Ussishkin, David. 1995. “The Destruction of Megiddo at the End of the Late Bronze Age and its Historical Significance.” Tel Aviv 22, no. 2: 240–267.

Ussishkin, David. 1996. “Excavations and Restoration Work at Tel Lachish 1985–1994: Third Preliminary Report.” Tel Aviv 23, no. 1: 3–60.

Ussishkin, David. 2004a. “A Synopsis of the Stratigraphical, Chronological and Historical Issues.” In The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994). Vol. 2. David Ussishkin et al., 50–122. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. No. 22. Tel Aviv, Israel: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology.

Ussishkin, David. 2004b. “Area GE: The Inner City-Gate.” In The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994). Vol. 2. David Ussishkin et al., 624–689. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. No. 22. Tel Aviv, Israel: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology.

Ussishkin, David. 2004c. “The Expedition and its Work.” In The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994). Vol. 1. David Ussishkin et al., 3–22. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University No. 22. Tel Aviv, Israel: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology.

Ussishkin, David. 2004d. “Section B: The Royal Judean Storage Jars and Seal Impressions From the Renewed Excavations.” In The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973–1994). Vol. 4. David Ussishkin et al., 2133–2147. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University No. 22. Tel Aviv, Israel: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology

Ussishkin, David. 2007. “Lachish and the Date of the Philistine Settlement in Canaan.” In The Synchronisation of Civilisations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. III, edited by Manfred Bietak and Ernst Czerny, 601–605. Proceedings of the SCIEM 2000—2nd EuroConference Vienna, 28th of May—1st of June 2003. Contributions to the Chronology of the Eastern Mediterranean. Vol. 9. Wien, Germany: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Ussishkin, David. 2014a. Biblical Lachish: A Tale of Construction, Destruction, Excavation and Restoration. Jerusalem, Israel: Israel Exploration Society and Biblical Archaeology Society.

Ussishkin, David. 2014b. “Sennacherib’s Campaign to Judah: The Archaeological Perspective With an Emphasis on Lachish and Jerusalem.” In Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. Edited by Isaac Kalimi and Seth Richardson, 75–103. Leiden/Boston: Koninklijke Brill NV.

Ussishkin, David. 2015. “Gath, Lachish and Jerusalem in the 9th Cent. B.C.E.—an Archaeological Reassessment.” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 131, no. 2: 129–149.

Van der Perre, Athena. 2014. “The Year 16 Graffito of Akhenaten in Dayr Abū Ḥinnis. A Contribution to the Study of the Later Years of Nefertiti.” Journal of Egyptian History 7, no. 1: 67–108.

van der Veen, Peter G. 2005. “A Revised Chronology and Iron Age Archaeology—An Update.” Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum 10: 49–51, 56.

van der Veen, Peter G. 2012. “Gedaliah’s Seal Material Revisited: Some Preliminary Notes on New Evidence from the City of David.” In New Inscriptions and Seals Relating to the Biblical World. Edited by Meir Lubetski and Edith Lubetski, 21–33. Society of Biblical Literature Archaeology and Biblical Studies, no. 19. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature.

Van Dijk, Jacobus. 1996. “Horemheb and the Struggle for the Throne of Tutankhamun.” Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology 7: 29–42.

Van Dijk, Jacobus. 2003. “The Amarna Period and Later New Kingdom (c. 1352–1069 BC).” In The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Edited by Ian Shaw, 265–307. New York, New York: Oxford University Press Inc.

Van Dijk, Jacobus. 2008. “New Evidence on the Length of the Reign of Horemheb.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 44: 193–200.

Velikovsky, Immanuel. 1950. Worlds in Collision. Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc.

Velikovsky, Immanuel. 1952. Ages in Chaos. Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc.

Velikovsky, Immanuel. 1977. Peoples of the Sea. Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc.

Weinstein, James M. 2012. “Egypt and the Levant in the Reign of Ramesses III.” In Ramesses III: The Life and Times of Egypt’s Last Hero. Edited by Eric H. Cline and David O’Connor, 160–180. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

Wilson, John Albert, and Thomas George Allen, eds. 1940. Medinet Habu—Volume 4. Festival Scenes of Rameses III. The University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publication, Vol. 51, Plates 193–249. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

Winlock, Herbert E. 1921. Bas-Reliefs from the Temple of Rameses I at Abydos. Papers. Vol. 1, Part I. New York, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Wiseman, D.J. 1956. Chronicles of the Chaldean Kings (626–556 B.C.) in the British Museum. London, United Kingdom: The Trustees of the British Museum.

Wright, G. Ernest. 1938. “Lachish: Frontier Fortress of Judah.” The Biblical Archaeologist 1, no. 4 (December): 21–30.

Yasur-Landau, Assaf. 2012. “The ‘Feathered Helmets’ of the Sea Peoples: Joining the Iconographic and Archaeological Evidence.” TALANTA—Proceedings of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society 44: 27–40.

Yurco, Frank J. 1986. “Merneptah’s Canaanite Campaign.” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 23: 189–215.

Yurco, Frank J. 1990. “3,200-Year-Old Picture of Israelites Found in Egypt.” Biblical Archaeology Review, 16, no. 5 (September/October): 20–22, 24–28, 32–34, 36–37.

Zammit, Abigail. 2016. The Lachish Letters: A Reappraisal of the Ostraca Discovered in 1935 and 1938 at Tell ed-Duweir. Volume II: Catalogues. Ph.D. dissertation. St. Antony’s College, University of Oxford, United Kingdom.

Zukerman, Alexander. 2009. “Chapter 7B: Notes on Pottery with Philistine, Cypriot and Aegean Affinities.” In Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean 1989–1996. Volume III: The 13th–11th Century BCE Strata in Areas N and S. Edited by Nava Panitz-Cohen and Amihai Mazar, 500–509. Israel, Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society.

Zukerman, Alexander, Trude Dothan, and Seymour Gitin. 2016. “A Stratigraphic and Chronological Analysis of the Iron Age I Pottery from Strata VII-IV.” In Tel Miqne-Ekron Excavations 1985–1988, 1990, 1992–1995 Field IV Lower—The Elite Zone. Part 1: The Iron Age I Early Philistine City. Edited by Trude Dothan, Yosef Garfinkel, and Seymour Gitin, 417–622. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Appendix A. The Assyrian and Babylonian Destruction Layers at Tel Lachish (701–587 BC)

Levels III–II at Tel Lachish are the best attested sequence of stratigraphy from the Iron Age period of ancient Judah (Ussishkin 2004a, 92). Although many ancient cities are documented in historical texts, rarely does written history have an absolute parallel in the stratigraphic sequence uncovered at a mound ruin. Tel Lachish, however, is a spectacular exception. Starkey’s incomplete excavation in the 1930s correlated the destruction of Level II with the Bible’s record of the early sixth-century BC assault on Lachish by the Babylonian army of Nebuchadnezzar II (Ussishkin 2004a, 88), mentioned in the book of Jeremiah (34:7). Two decades later, Olga Tufnell identified Level III as the fortress city famously besieged by Sennacherib of Assyria during his third campaign in 701 BC (Roux 1992, 320; Ussishkin 2004a, 88–89; 2014a, 220–221, 271–275). This earlier siege is documented briefly in 2 Kings (18:13–14, 17, 19:8), 2 Chronicles (32:9) and Isaiah (36:2, 37:8); the campaign is dramatically retold in the Annals of Sennacherib (Luckenbill 1924, 32–34; 1927, 118–121, 142–143, 154; Ussishkin 2014a, 271–277); and the fate of the city is visually described on the magnificent Lachish Reliefs (now in room 10b at the British Museum)—recovered in 1849 by Sir Austen Henry Layard from the ruins of Nineveh (Layard 1853, 125– 129; Ussishkin 1980; 2014b, 85–89). Together with the excellent stratigraphy and well-defined pottery assemblages preserved at the mound, these primary sources establish the stratigraphic sequence of Levels III–II within the timeline of ancient history, making Tel Lachish the archaeological type-site for the Iron Age IIB–C period in the region of Israel (Kang 2016, 283–284; Ussishkin 2004a, 92; 2014a, 357).

Level III—Iron Age IIB (c. 750–701 BC)

Lachish Level III was a prosperous city with monumental buildings and powerful fortifications; it was encircled by a revetment wall halfway up the slope; a second wall, constructed with mud bricks on a stone foundation, stood on the upper edge of the mound (Ussishkin 2014a, 223–227; 2014b, 77). A massive gatehouse overlooked the southwestern approach to the city, and a Palace-Fort (Palace C) towered on the summit (Ussishkin 2004a, 83; 2014a, 227–262; 2014b, 77). During this period, Lachish rivalled nearby Jerusalem as the most powerful and wealthy city within the territory of the biblical kingdom of Judah.

In 1977, excavations by the Tel Aviv Institute confirmed the existence of a large siege ramp on the southwest corner of the site (Area R) (Ussishkin 1990, 64–69; 2004b; 2014a, 282–286, 289–295; 2014b 80– 81). The narrow area approaching the ramp summit was littered with several hundred iron arrowheads (Gottlieb 2004; Ussishkin 1990, 75; 2004b, 736, 738), many still imbedded in the brick debris from the collapsed walls (Ussishkin 2004b, 736, 754–756, 760–762); armor fragments, slingstones, Assyrianstyle pottery (Ussishkin 1996, 18–19; 2004c, 1904– 1905), and other siege equipment were uncovered on the ramp surface (Ussishkin 1990, 72–76; 1996, 20–23; 2004b, 732–739; 2014a, 301–312, 317–318; 2014b, 83–84). A counter-ramp erected by the city’s defenders was identified facing the area where the brick fortifications were breached (Ussishkin 1984; 1990, 69–71; 2004b, 723–732; 2014a, 296–300; 2014b, 81). More arrowheads were found concentrated in the area of the inner gatehouse on the western side of the mound; still others were found scattered among the residential buildings (Ussishkin 2014a, 311, 314).