Research conducted by Answers in Genesis staff scientists or sponsored by Answers in Genesis is funded solely by supporters’ donations.

Abstract

Within the church, the creation vs. evolution debate is often looked upon as a side issue or as unimportant. However, nothing could be further from the truth. Because of the acceptance of evolutionary theory, many have chosen to re-interpret the Bible with regards to its teaching on creation, the history of Adam and the global catastrophic flood in Noah’s day. Consequently, the very teachings of Jesus are being attacked by those who state that, because of His human nature, there is error in some of His teaching regarding earthly things such as creation. While scholars admit that Jesus affirmed such things as Adam, Eve, Noah and the Flood, they believe that Jesus was wrong on these matters.

The problem with this theory is that it raises the question of Jesus’s reliability, not only as a prophet, but more importantly as our sinless Savior. These critics go too far when they say that because of Jesus’s human nature and cultural context, He taught and believed erroneous ideas.

Keywords: Jesus, deity, humanity, prophet, truth, teaching, creation, kenosis, error, accommodation.

Introduction

In His humanity, Jesus was subject to everything that humans are subject to, such as tiredness, hunger, and temptation. But does this mean that like all humans He was subject to error? Much of the focus on the person of Jesus in the church today is on His divinity, to the point where, often, aspects of His humanity are overlooked, which can in turn lead to a lack of understanding of this critical part of His nature. For example, it is argued that in His humanity Jesus was not omniscient and that this limited knowledge would have made Him capable of error. It is also believed that Jesus accommodated Himself to the prejudices and erroneous views of the Jewish people of the first century AD, accepting some of the untrue traditions of that time. This, therefore, nullifies His authority on critical questions. For the same reasons, it is not only certain aspects of Jesus’s teaching, but also those of the apostles that are seen as erroneous. Writing for the theistic evolutionist organization Biologos, Kenton Sparks argues that because Jesus, as a human, operated within His finite human horizon, then He would have made errors:

If Jesus as a finite human being erred from time to time, there is no reason at all to suppose that Moses, Paul, John [sic] wrote Scripture without error. Rather, we are wise to assume that the biblical authors expressed themselves as human beings writing from the perspectives of their own finite, broken horizons. (Sparks 2010, p. 7)

To believe our Lord was able to err—and did err in the things He taught—is a severe accusation and needs to be taken seriously. In order to demonstrate that the claim that Jesus erred in His teaching is itself erroneous, it is necessary to evaluate different aspects of Jesus’s nature and ministry. First, this paper will look at the divine nature of Jesus and whether He emptied Himself of that nature, followed by the importance of Jesus’s ministry as a prophet and His claims of the teaching the truth. It will then consider whether Jesus erred in His human nature, and whether as a result of error in Scripture (since humans were involved in its writing) Christ erred in His view of the Old Testament. Finally, the paper will explore the implications of Jesus’s teaching allegedly being false.

The Divine Nature of Jesus—He Existed Before Creation

Genesis 1:1 tells us that “In the

beginning God created the heavens and the earth.

” In John 1:1

we read the same words, “In the beginning . . .

” which

follows the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament. John informs

us in John 1:1 that in the beginning was the Word (logos) and that the

Word was not only with God but was God. This Word is the one who brought all

things into being at creation (John 1:3). Several verses

later, John writes that the Word who was with God in the beginning “became

flesh and dwelt among us

” (John 1:14). Notice that

John does not say that the Word stopped being God. The verb “. . . ‘became’

[egeneto] here does not entail any change in the essence of the Son.

His deity was not converted into our humanity. Rather, he assumed our human

nature” (Horton 2011, p. 468). In fact, John uses a very particular term here,

skenoo “dwelt”, which means he “pitched his tent” or “tabernacled” among

us. This is a direct parallel to the Old Testament record of when God “dwelt”

in the tabernacle that Moses told the Israelites to construct (Exodus 25:8–9; 33:7). John is telling us that God “dwelt” or “pitched his

tent” in the physical body of Jesus.

In the incarnation, it is important to understand that Jesus’s human nature

did not replace His divine nature. Rather, His divine nature dwelt in a human

body. This is affirmed by Paul in Colossians 1:15–20, especially in verse 19,

“For it pleased the Father that in Him all the fullness should dwell

,” Jesus

was fully God and fully man in one person.

The New Testament not only explicitly states that Jesus was fully God, it

also recounts events that demonstrate Jesus’ divine nature. For example, while

Jesus was on earth, He healed the sick (Matthew 8–9) and forgave sins (Mark 2). What is more, He accepted worship from people (Matthew 2:2; 14:33; 28:9).

One of the greatest examples of this comes from the lips of Thomas when he exclaims

in worship before Jesus, “My Lord and my God!

” (John 20:28). The confession

of deity here is unmistakable, as worship is only meant to be given to God (Revelation 22:9); yet Jesus never rebuked Thomas, or others, for this. He also did many

miraculous signs (John 2; 6; 11) and had the prerogative to judge people (John 5:27) because He is the Creator of the world (John 1:1–3; 1 Corinthians 8:6; Ephesians 3:9; Colossians 1:16; Hebrews 1:2; Revelation 4:11).

Furthermore, the reactions of those around Jesus demonstrated that He viewed

Himself as divine and truly claimed to be divine. In John 8:58, Jesus said to

the Jewish religious leaders, “Most assuredly, I say to you, before Abraham

was, I am

”. This “I am” statement was Jesus’s clearest example of His proclamation

“I am Yahweh,” from its background in the book of (Isaiah 41:4; 43:10–13, 25; 48:12—see also Exodus 3:14). This divine self-disclosure of Jesus’s explicit

identification of Himself with Yahweh of the Old Testament is what led the Jewish

leaders to pick up stones to throw at Him. They understood what Jesus was saying,

and that is why they wanted to stone Him for blasphemy. A similar incident takes

place in John 10:31. The leaders again wanted to stone Jesus after He said “I

and the Father are one,

” because they knew He was making Himself equal with

God. Equality indicates His deity, for who can be equal to God? Isaiah 46:9

says: “Remember the former things of old, For I am God, and there is no other;

I am God, and there is none like Me.

” If there is no one like God and yet Jesus

is equal to God (Philippians 2:6), what does this say of Him, except that He

must be God? The only thing that is equal to God is God.

In the Incarnation Did Jesus Empty Himself of His Divine Nature?

Kenotic Theology—(Philippians 2:5–8)

A question that needs to be asked is whether Jesus emptied Himself of His divine nature in His incarnation. In the seventeenth century, German scholars debated the issue of Christ’s divine attributes while He was on earth. They argued that because there is no reference in the gospels to Christ making use of all of His divine attributes (such as omniscience) that He abandoned the attributes of His divinity in His incarnation (McGrath 2011, p. 293). Gottfried Thomasius (1802–1875) was one of the main proponents of this view who explained the incarnation as “the self-limitation of the Son of God” (Thomasius, Dorner, and Biedermann 1965, p. 46). He reasoned that the Son could not have maintained His full divinity during the incarnation (Thomasius, Dorner, and Biedermann 1965, pp. 46–47). Thomasius believed that the only way for a true incarnation to take place was if the Son “‘gave himself over into the form of human limitation.”’ (Thomasius, Dorner, and Biedermann 1965, pp. 47–48). He found his support for this in Philippians 2:7, defining the kenosis as:

[T]he exchange of the one form of existence for the other; Christ emptied of the one and assumed the other. It is thus an act of free self-denial, which has as its two moments the renunciation of the divine condition of glory, due him as God, and the assumption of the humanly limited and conditioned pattern of life. (Thomasius, Dorner, and Biedermann 1965, p. 53)

Thomasius separated the moral attributes of God: truth, love, and holiness, from the metaphysical attributes: omnipotence, omnipresence, and omniscience. Thomasius not only believed that Christ gave up the use of these attributes, (omnipotence, omnipresence, omniscience) but that He did not even possess them during the incarnation (Thomasius, Dorner, and Biedermann 1965, pp. 70–71). Because of Christ’s self-emptying in Philippians 2:7, it was believed that Jesus was limited essentially by the opinions of His time. Robert Culver comments on the belief of Thomasius and other scholars who held to a kenotic theology:

Jesus’ testimony to the inerrant authority of the Old Testament . . . is negated. He simply had given up divine omniscience and omnipotence and hence didn’t know any better. Some of these scholars earnestly desired a way to remain orthodox and to go with the flow of what was deemed to be scientific truth about nature and about the Bible as an inspired book not necessarily true in every respect. (Culver 2006, p. 510)

It is critical, therefore, to ask what Paul means when he says that Jesus emptied Himself. Philippians 2:5–8 says:

In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus: Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death—even death on a cross!

There are two key words in these verses that help in understanding the nature of Jesus. The first key word is the Greek morphē (form). Morphē

covers a broad range of meanings and therefore we are heavily dependent on the immediate context to discover its specific nuance. (Silva 2005, p. 101)

In Philippians 2:6 we are helped by two factors to discover the meaning of morphē.

In the first place, we have the correspondence of morphē theou with isa theō. . . . “in the form of God” is equivalent to being “equal with God.” . . . . In the second place, and most important, morphē theou is set in antithetical parallelism to μορφην δουλου (morphēn doulou, form of a servant), an expression further defined by the phrase εν ομοιωματι ανθρωπων (en homoiōmati anthrōpōn, in the likeness of men). (Silva 2005, p. 101)

The parallel phrases show that morphē refers to outward appearance. In Greek literature the term morphē has to do with “external appearance” (Behm 1967, pp. 742–743) which is visible to human observation. “Similarly, the word form in the Greek OT (LXX) refers to something that can be seen [Judges 8:18; Job 4:16; Isaiah 44:13]” (Hansen 2009, p. 135). Christ did not cease to be in the form of God in the incarnation, but taking on the form of a servant He became the God-man.

The second key word is ekenosen from which we get the kenosis doctrine. Modern English Bibles translate verse 7 differently:

New International Version/Today’s New International Version: “

rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant being made in human likeness.”English Standard Version: “

but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men.”New American Standard Bible: “

but emptied Himself, taking the form of a bond-servant, and being made in the likeness of men.”New King James Version: “

but made Himself of no reputation, taking the form of a bondservant, and coming in the likeness of men.”New Living Translation: “

Instead, he gave up his divine privileges; he took the humble position of a slave and was born as a human being. When he appeared in human form.”

It is debatable from a lexical standpoint whether “emptied himself,” “made Himself of no reputation,” or “gave up his divine privileges” are even the best translations. The New International Version/Today’s New International Version translation “made himself nothing” is probably more supportable (Hansen 2009, p. 149; Silva 2005, p. 105; Ware 2013). Philippians 2:7, however, does not say that Jesus emptied Himself of anything in particular; all it says is that he emptied Himself. New Testament scholar George Ladd comments:

The text does not say that he emptied himself of the morphē theou [form of God] or of equality with God . . . All that the text states is that “he emptied himself by taking something else to himself, namely, the manner of being, the nature or form of a servant or slave.” By becoming human, by entering on a path of humiliation that led to death, the divine Son of God emptied himself. (Ladd 1994, p. 460)

It is pure conjecture to argue from this verse that Jesus gave up any or all

of His divine nature. He may have given up or suspended the use of some of His

divine privileges, perhaps, for example, His omnipresence or the glory that

He had with the Father in heaven (John 17:5), but not His divine power or knowledge.

“The humiliation,” of Jesus is not therefore seen in His becoming man (anthropos)

or a man (aner) but that “as man” (hos anthropos) “‘he humbled

himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross

’ (Philippians 2:8)” (Culver 2006, p. 514).

The fact that Jesus did not give up His divine nature can be seen when He was on the Mount of Transfiguration and the disciples saw His glory (Luke 9:28–35) since here there is an association with the glory of God’s presence in Exodus 34:29–35. In the incarnation Jesus was not exchanging His deity for humanity but suspending the use of some of His divine powers and attributes (cf. 2 Corinthians 8:9). Jesus’s emptying of Himself was a refusal to cling to His advantages and privileges as God. We can also compare how Paul uses this same term, kenoo, which only appears four other times in the New Testament (Romans 4:14; 1 Corinthians 1:17; 9:15; 2 Corinthians 9:3). In Romans 4:14 and 1 Corinthians 1:17, it means to make void, that is, deprive of force, render vain, useless, or of no effect. In 1 Corinthians 9:15 and 2 Corinthians 9:3 it means to make void, that is, to cause a thing to be seen to be empty, hollow, false (Thayer 2007, p. 344). In these instances it is clear that Paul’s use of kenoo is used figuratively rather than literally (Berkhof 1958, p. 328; Fee 1995, p. 210; Silva 2005, p. 105). Additionally, in Philippians 2:7 “to press for a literal meaning of ‘emptying’ ignores the poetic context and nuance of the word” (Hansen 2009, p. 147). Therefore, in Philippians 2:7 it is perhaps more accurate to see “emptying” as Jesus pouring Himself out, in service, in an expression of divine self-denial (2 Corinthians 8:9). Jesus’s service is explained in Mark 10:45: “For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life a ransom for many.” In practise, this meant in the incarnation that Jesus:

- Took the form of a servant

- Was made in the likeness of men

- Humbled himself becoming obedient to death on the cross.

In His incarnation Jesus did not cease to be God, or cease in any way to have the authority and knowledge of God.

Jesus as a Prophet

In His state of humiliation, part of Jesus’s ministry was to speak God’s message to the people. Jesus referred to Himself as a prophet (Matthew 13:57; Mark 6:4; Luke 13:33) and was declared to have done a prophet’s work (Matthew 13:57; Luke 13:33; John 6:14). Even those who did not understand that Jesus was God accepted Him as a prophet, (Luke 7:15–17, Luke 24:19, John 4:19; 6:14; 7:40; 9:17). Furthermore, Jesus introduced many of His sayings by “amen” or “truly” (Matthew 6:2, 5, 16). I. Howard Marshall says of Jesus:

[Jesus] made no claim to prophetic inspiration; no “thus says the Lord” fell from his lips, but rather he spoke in terms of his own authority. He claimed the right to give the authoritative interpretation of the law, and he did so in a way that went beyond that of the prophets. He thus spoke as if he were God. (Marshall 1976, pp. 49–50)

In the Old Testament, Deuteronomy 13:1–5 and 18:21–22 provided the people of Israel with two tests to discern true prophets from false prophets.

First, a true prophet’s message had to be consistent with earlier revelation.

Second, a true prophet’s predictions always had to come true.

Deuteronomy 18:18–19 foretells of a prophet whom God would raise up from His

own people after Moses died: “I will raise up for them a Prophet like you from

among their brethren, and will put My words in His mouth, and He shall speak

to them all that I command Him

” (Deuteronomy 18:18). This is properly referred

to in the New Testament as having been fulfilled in Jesus Christ (John 1:45; Acts 3:22–23; 7:37). Jesus’s teaching had no origin in human ideas but came

entirely from God. In His role as prophet, Jesus had to speak God’s word to

God’s people. Therefore He was subject to God’s rules concerning prophets. In

the Old Testament, if a prophet was not correct in his predictions he would

be stoned to death as a false prophet by order of God (Deuteronomy 13:1–5; 18:20).

For a prophet to have credibility with the people, his message must be true,

as he has no message of his own but can only report what God has given him.

This is because prophecy had its origin in God and not man (Habakkuk 2:2–3; 2 Peter 1:21).

In His prophetic role, Christ represents God the Father to mankind. He came as a light to the world (John 1:9; 8:12) to show us God and bring us out of darkness (John 14:9–10). In John 8:28–29 Jesus also showed evidence of being a true prophet—that of living in close relation with His Father, passing on His teaching (cf. Jeremiah 23:21–23):

When you lift up the Son of Man, then you will know that I am He, and that I do nothing of Myself; but as My Father taught Me, I speak these things. And He who sent Me is with Me. The Father has not left Me alone, for I always do those things that please Him.

Jesus had the absolute knowledge that everything He did was from God. What He said and did is absolute truth because His Father is “truthful” (John 8:26). Jesus only spoke that which His Father told Him to say (John 12:49–50), so it had to be correct in every way. If Jesus as a prophet was wrong in the things He said, then why would we acclaim Him as the Son of God? If Jesus is a true prophet, then His teaching regarding Scripture must be taken seriously as absolute truth.

Jesus’s Teaching and Truth

Since God himself is the measure of all truth and Jesus was co-equal with God, he himself was the yardstick by which truth was to be measured and understood. (Letham 1993, p. 92)

In John 14:6 we are told that Jesus not only told the truth but that He was, and is, truth. Scripture portrays Jesus as the truth incarnate (John 1:17). Therefore, if He is the truth, He must always tell the truth and it would have been impossible for Him to speak or think falsehood. Much of Jesus’s teaching began with the phrase “Truly, truly I say . . .” If Jesus taught anything in error, even if it was from ignorance (for example, the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch), He would not be the truth.

To err may be human for us. Falsehood, however, is rooted in the nature of the devil (John 8:44), not the nature of Jesus who speaks the truth (John 8:45–46). The Father is the only true God (John 7:28; 8:26; 17:3) and Jesus taught only what the Father had given to Him (John 3:32–33; 8:40; 18:37). Jesus testifies about the Father, who in turn testifies concerning the Son (John 8:18–19; 1 John 5:10–11), and they are one (John 10:30). The gospel of John shows emphatically that Jesus’s teaching and words are the teaching and words of God. Three clear examples of this are:

And the Jews marveled, saying, “How does this Man know letters, having never studied?” Jesus answered them and said, “My doctrine is not Mine, but His who sent Me. If anyone wills to do His will, he shall know concerning the doctrine, whether it is from God or whether I speak on My own authority.”(John 7:15–17)

I know that you are Abraham’s descendants, but you seek to kill Me, because My word has no place in you. I speak what I have seen with My Father, and you do what you have seen with your father. . . . But now you seek to kill Me, a Man who has told you the truth which I heard from God. Abraham did not do this.(John 8:37–38, 40)

For I have not spoken on My own authority; but the Father who sent Me gave Me a command, what I should say and what I should speak. And I know that His command is everlasting life. Therefore, whatever I speak, just as the Father has told Me, so I speak.(John 12:49–50)

In John 12:49–50 “Not only is what Jesus says just what the Father has told him to say, but he himself is the Word of God, God’s self-expression (1:1)” (Carson 1991, p. 453). The authority behind Jesus’s words are the commands that are given to Him by the Father (and Jesus always obeyed the Father’s commands; John 14:31). Jesus’s teaching did not originate in human ideas but came from God the Father, which is why it is authoritative. His very own words were spoken in full authorization from the Father who sent Him. The authority of Jesus’s teaching then rests upon the unity between Himself and the Father. Jesus is the embodiment, revelation, and messenger of truth to mankind; and it is the Holy Spirit who conveys truth about Jesus to the unbelieving world through believers (John 15:26–27; 16:8–11). Again, the point is that if there was error in Jesus’s teaching, then He is a false and unreliable teacher. However, Jesus was God incarnate, and God and falsehood can never be reconciled with each other (Titus 1:2; Hebrews 6:18).

Jesus’s Human Nature

It is important to understand that in the incarnation, not only did Jesus retain His divine nature, He also took on a human nature. With respect to His divine nature, Jesus was omniscient (John 1:47–51; 4:16–19, 29), having all the attributes of God, yet in His human nature He had all the limitations of being human, which included limitations in knowing. The true humanity of Jesus is expressed throughout the gospels, which tell us that Jesus was wrapped in ordinary infant clothing (Luke 2:7), grew in wisdom as a child (Luke 2:40, 52), and was weary (John 4:6), was hungry (Matthew 4:4), was thirsty (John 19:28), was tempted by the devil (Mark 4:38), and was sorrowful (Matthew 26:38a). The incarnation should be viewed as an act of addition and not as an act of subtraction of Jesus’s nature:

When we think about the Incarnation, we don’t want to get the two natures mixed up and think that Jesus had a deified human nature or a humanized divine nature. We can distinguish them, but we can’t tear them apart because they exist in perfect unity. (Sproul 1996)

For example, in Mark 13:32 where Jesus is talking about His return, He says,

“But of that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, nor the

Son, but only the Father.

” Does this mean that Jesus was somehow limited? How

should we handle this statement by Jesus? The text seems straightforward in

saying there was something Jesus did not know. Jesus’s teaching shows that what

He knew or did not know was a conscious self-limitation. The God-man possessed

divine attributes, or He would have ceased to be God, but He chose not always

to employ them. The fact that Jesus told His disciples that He did not know

something is an indication that He did not teach untruths and this is confirmed

by His statement, “if it were not so, I would have told you

” (John 14:2). Furthermore,

ignorance of the future is not the same as making an erroneous statement. If

Jesus had predicted something that did not take place, then that would be an

error.

The question that now needs to be asked is this: Was Jesus in His humanity capable of error in the things he taught? Does our human capacity to err apply to the teaching of Jesus? Because of His human nature, questions are raised about Jesus’s beliefs concerning certain events in Scripture. The Chicago Statement on Biblical Hermeneutics (1982) states: “We deny that the humble, human form of Scripture entails errancy any more than the humanity of Christ, even in His humiliation, entails sin.” Arguing against the position, Kenton Sparks, Professor of Biblical Studies at Eastern University, in his book God’s Word in Human Words, states:

First, the Christological argument fails because, though Jesus was indeed sinless, he was also human and finite. He would have erred in the usual way that other people err because of their finite perspectives. He misremembered this event or that, and mistook this person for someone else, and thought—like everyone else—that the sun was literally rising. To err in these ways simply goes with the human territory. (Sparks 2008, pp. 252–253)

First of all, it should be noted that nowhere in the gospels is there any evidence that Jesus either misremembered any event or mistook any person for another, nor does Sparks provide evidence for this. Secondly, the language used in Scripture to describe the sun’s rising (for example, Psalm 104:22) and movement of the earth are literal only in a phenomenological sense as it is described from the viewpoint of the observer. Moreover, this is still done today in weather reports when the reporter uses terminology such as “sunrise tomorrow will be at 5 a.m.”

Because of the impact evolutionary ideology has had in the scientific realm as well as in theology, it is reasoned that Jesus’s teaching on things such as creation and the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch was simply wrong. Jesus would have been unaware of evolution as it relates to the critical approach to the authorship of the Old Testament, the Documentary Hypothesis. It is reasoned that in His humanity He was limited by the opinions of His time. Therefore, He could not be held accountable for holding to a view of Scripture that was prevalent in the culture. It is argued that Jesus erred in what He taught because He was accommodating the erroneous Jewish traditions of His time. For example, Peter Enns objects to idea that Jesus’s belief in the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch is valid, since He simply accepted the cultural tradition of His day:

Jesus seems to attribute authorship of the Pentateuch to Moses (e.g., John 5:46–47). I do not think, however, that this presents a clear counterpoint, mainly because even the most ardent defenders of Mosaic authorship today acknowledge that some of the Pentateuch reflects updating, but taken at face value this is not a position that Jesus seems to leave room for. But more important, I do not think that Jesus’s status as the incarnate Son of God requires that statements such as John 5:46–47 be understood as binding historical judgments of authorship. Rather, Jesus here reflects the tradition that he himself inherited as a first-century Jew and that his hearers assumed to be the case. (Enns 2012, p. 153)

Like Enns, Sparks also uses the accommodation theory to argue for human errors in Scripture (Sparks 2008, pp. 242–259). He believes that the Christological argument cannot serve as an objection to the implications of accommodation (Sparks 2008, p. 253) and that God does not err in the Bible when He accommodates the errant views of Scripture’s human audience (Sparks 2008, p. 256).

In his objection to the validity of Jesus’s belief in the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch, Enns is too quick in downplaying the divine status of Jesus in relation to His knowledge of the authorship of the Pentateuch. This overlooks whether the divinity of Christ meant anything in terms of an epistemological relevance to His humanity, and raises the question of how the divine nature relates to the human nature in the one person. We are told on several occasions, for example, that Jesus knew what people were thinking (Matthew 9:4; 12:25) which is a clear reference to His divine attributes. A. H. Strong gives a good explanation as to how the personality of Jesus’s human nature existed in union with His divine nature:

[T]he Logos did not take into union with himself an already developed human person, such as James, Peter, or John, but human nature before it had become personal or was capable of receiving a name. It reached its personality only in union with his own divine nature. Therefore we see in Christ not two persons—a human person and a divine person—but one person, and that person possessed of a human nature as well as a divine. (Strong 1907, p. 679)

There is a personal union between the divine and human nature with each nature entirely preserved in its distinctness, yet in and as one person. Although, some appeal to Jesus’s divinity in order to affirm Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch (Packer 1958, pp. 58–59), it is not necessary to do so, since:

There is no mention in the Gospels of Jesus’ divinity overwhelming his humanity. Nor do the Gospels refer his miracles to his divinity and refer his temptation or sorrow to his humanity, as if he switched back and forth from operating according to one nature to operating according to another. Rather, the Gospels routinely refer Christ’s miracles to the Father and the Spirit . . . [Jesus] spoke what he heard from the Father and as he was empowered by the Spirit. (Horton 2011, p. 469)

The context of John 5:45–47 is important in understanding the conclusions we draw concerning the truthfulness of what Jesus taught. In John 5:19 we are told that Jesus can do nothing of Himself. In other words, He does not act independently of the Father, but He only does what He sees the Father doing. Jesus has been sent into the world by God to reveal truth (John 5:30, 36) and it is this revelation from the Father that enabled Him to do “greater works.” Elsewhere in John we are told that the Father teaches the Son (John 3:32–33; 7:15–17; 8:28, 37–38; 12:49–50). Jesus is not only one with the Father but is also dependent upon Him. Since the Father cannot be in error or lie (Numbers 23:19; Titus 1:2), and because Jesus and the Father are one (John 10:30), to accuse Jesus of error or falsehood in what He knew or taught is to accuse God of the same thing.

Jesus went on to acknowledge that the Old Testament required a minimum of two or three witnesses to establish the truthfulness of one’s claim (Deuteronomy 17:6; 19:15). Jesus produces several witnesses corroborating His claim of equality with God:

- John the Baptist (John 5:33–35)

- Jesus’s works (John 5:36)

- God the Father (John 5:37)

- The Scriptures (John 5:39)

- Moses (John 5:46)

Jesus told the Jewish leaders that it is Moses, one of the witnesses, who will hold them accountable for their unbelief in what he wrote concerning Him, and that it is he who will be their accuser before God. New Testament scholar Craig Keener comments:

In Palestinian Judaism, “accusers” were witnesses against the defendant rather than official prosecutors (cf. 18:29), an image which would be consistent with other images used in the gospel tradition (Matt 12:41–42; Luke 11:31–32). The irony of being accused by a person or document in which one trusted for vindication would not be lost on an ancient audience. (Keener 2003, pp. 661–662)

In order for the accusation to hold up, however, the document or witnesses need to be reliable (Deuteronomy 19:16–19) and if Moses did not write the Pentateuch, how then can the Jews be held accountable by him and his writings? It was Moses who brought the people of Israel out of Egypt (Acts 7:40), gave them the Law (John 7:19), and brought them to the Promised Land (Acts 7:45). It was Moses who wrote about the coming prophet that God would send Israel to whom they should listen (Deuteronomy 18:15; Acts 7:37). What is more, it is God who puts the words into the mouth of this prophet (Deuteronomy 18:18). Moreover, Jesus

opposed the pseudo-authority of untrue Jewish traditions . . . . [and] disagrees with a pseudo-oral source [Mark 7:1–13], the false attribution of Jewish oral tradition to Moses. (Beale 2008, p. 145)

The basis for the truthfulness and inerrancy of what Jesus taught does not have to be resolved by appealing to His divine knowledge (although it can be), but can be understood from His humanity through His unity with the Father, which is why His teaching is true.

Furthermore, the New Testament strongly favors the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch (Matthew 8:4; 23:2; Luke 16:29–31; John 1:17, 45; Acts 15:1; Romans 9:15; 10:5). However, because of their belief in the “overwhelming evidence” for the documentary hypothesis, scholars (for example, Sparks 2008, p. 165) seem to come to the New Testament believing that the evidence of the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch must be explained away in order to be consistent with their conclusions. The simple fact is that scholars who reject the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch, and embrace an accommodation approach to the evidence of the New Testament, are as unwilling as the Jewish leaders (John 5:40) in not wanting to listen to the words of Jesus on this subject.

The accommodation approach to the teaching of Jesus also raises the issue of whether He was mistaken on other such issues, as Gleason Archer explains:

Such an error as this, in matters of historical fact that can be verified, raises a serious question as to whether any of the theological teaching, dealing with metaphysical matters beyond our powers of verification, can be received as either trustworthy or authoritative. (Archer 1982, p. 46)

The accommodation approach also leaves us with a Christological problem. Since Jesus clearly understood that Moses wrote about Him, this creates a serious moral problem for Christians, as we are told to follow the example set by Christ (John 13:15; 1 Peter 2:21) and have his attitude (Philippians 2:5). Yet, if Christ is shown to be approving falsehood in some areas of His teaching, it opens a door for us to affirm falsehood in some areas as well. The belief that Jesus accommodated His teaching to the beliefs of his first century hearers does not square with the facts. New Testament scholar John Wenham in his book Christ and the Bible comments on the idea that Jesus accommodated His teaching to the beliefs of His first century hearers:

He is not slow to repudiate nationalist conceptions of Messiahship; He is prepared to face the cross for defying current misconceptions . . . Surely He would have been prepared to explain clearly the mingling of divine truth and human error in the Bible, if He had known such to exist. (Wenham 1994, p. 27)

For those who hold to an accommodation position, this overlooks the fact that Jesus never hesitated to correct erroneous views common in the culture (Matthew 7:6–13, 29). Jesus was never constrained by the culture of his day if it went against God’s Word. He opposed those who claimed to be experts on the Law of God, if they were teaching error. His numerous disputes with the Pharisees are testament to this (Matthew 15:1–9; 23:13–36). The truth of Christ’s teaching is not culturally bound, but transcends all cultures and remains unaltered by cultural beliefs (Matthew 24:35; 1 Peter 1:24–25). Those who claim that Jesus in His humanity was susceptible to error and therefore merely repeated the ignorant beliefs of His culture are claiming to have more authority, and to be wiser and more truthful than Jesus.

Much of Christian teaching focuses, rightly, on the death of Jesus. However,

in focusing on the death of Christ we often neglect the teaching that Jesus

lived a life of perfect obedience to the Father. Jesus not only died for us;

He also lived for us. If all Jesus had to do was to die for us, then He could

have descended from heaven on Good Friday, gone straight to the cross, risen

from the dead and ascended back into heaven. Jesus did not live for 33 years

for no reason. Whilst on earth Christ did the Father’s will (John 5:30), taking

specific actions, teaching, miracle-working, obeying the Law in order to “fulfill

all righteousness

” (Matthew 3:15). Jesus, the last Adam (1 Corinthians 15:45),

came to succeed where the first Adam had failed in keeping the law of God. Jesus

had to do what Adam failed to do in order to fulfill the required sinless life

of perfection. Jesus did this so that His righteousness could be transferred

to those who put their faith in Him for the forgiveness of sins (2 Corinthians 5:21; Philippians 3:9).

We must remember that in His humanity, Jesus, was not superman but a real man.

The humanity of Jesus and the deity of Jesus do not mix directly with one another.

If they did, then that would mean that the humanity of Jesus would actually

become super-humanity. And if it is super-humanity, it is not our humanity.

And if it is not our humanity, then He cannot be our substitute since He must

be like us (Hebrews 2:14–17). Although the genuine humanity

of Jesus did involve tiredness and hunger, it did not prevent Him from doing

what pleased His Father (John 8:29) and speaking the

truth He heard from God (John 8:40). Jesus did nothing on His own authority

(John 5:19, 30; 6:38; 7:16, 28; 8:16). He had the absolute knowledge that everything

He did was from God, including speaking what He had heard and had been taught

by the Father. In John 8:28 Jesus said: ““I do nothing of Myself; but as My Father

taught Me, I speak these things.

” New Testament scholar Andreas Kostenberger

notes that,

Jesus as the sent Son, again affirms his dependence on the Father, in keeping with the Jewish maxim that “a man’s agent [šālîah] is like the man himself.” (Kostenberger 2004, p. 260)

Just as God speaks the truth and no error can be found in Him, so it was with His sent Son. Jesus was not self-taught; rather His message came directly from God and, therefore, it was ultimately truth (John 7:16–17).

Scripture and Human Error

It has long been recognized that both Jesus and the apostles accepted Scripture as the flawless Word of the living God (John 10:35; 17:17; Matthew 5:18; 2 Timothy 3:16; 2 Peter 1:21). Unfortunately, this view of Scripture is attacked by many today, mainly because critics assume that since humans were involved in the process of writing Scripture, their capacity to err would result in the presence of errors in Scripture. The question that needs to be asked is whether the Bible contains error because it was written by human authors.

Many people are familiar with the Latin adage errare humanum est—to err is human. For instance, what person would ever claim to be without error? For this reason, the Swiss, neo-orthodox, theologian Karl Barth (1886–1968), whose view of Scripture is still influential in certain circles within the evangelical community, believed that: “we must dare to face the humanity of the biblical texts and therefore their fallibility . . .” (Barth 1963, p. 533). Barth believed that Scripture contained error because human nature was involved in the process:

As truly as Jesus died on the cross, as Lazarus died in Jn. 11, as the lame were lame, as the blind were blind . . . so, too, the prophets and apostles as such, even in their office, even in their function as witnesses, even in the act of writing down their witness, were real, historical men as we are, and therefore sinful in their action, and capable and actually guilty of error in their spoken and written word. (Barth 1963, p. 529)

Barth’s ideas, as well as the end results of higher criticism, are still making an impression today, as can be seen in Kenton Sparks’s work (Sparks 2008, p. 205). Sparks believes that although God is inerrant, because he spoke through human authors their “finitude and fallenness” resulted in a flawed biblical text (Sparks 2008, pp. 243–244).

In classic postmodern language Sparks states:

Orthodoxy demands that God does not err, and this implies, of course, that God does not err in Scripture. But it is one thing to argue that God does not err in Scripture; it is quite another thing that the human authors of Scripture did not err. Perhaps what we need is a way of understanding Scripture that paradoxically affirms inerrancy while admitting the human errors in Scripture. (Sparks 2008, p. 139)

Sparks’s claim of an inerrant Scripture that is errant is founded

in contemporary postmodern hermeneutical theories which emphasize the roll [sic] of the reader in the interpretive process and human fallibility as agents and receptors of communication. (Baugh 2008)

Sparks attributes the “errors” in Scripture to the fact that humans err: the Bible is written by humans, therefore its statements often reflect “human limitations and foibles” (Sparks 2008, p. 226). For both Barth and Sparks, an inerrant Bible is worthy of the charge of docetism (Barth 1963, pp. 509–510; Sparks 2008, p. 373).

Barth’s view of inspiration seems to be influencing many today in how they understand Scripture. Barth believed that God’s revelation takes place through His actions and activity in history; revelation then for Barth is seen as an “‘event”’ rather than coming through propositions (a proposition is a statement describing some reality that is either true or false; Beale 2008, p. 20). For Barth, the Bible is a witness to revelation but is not revelation itself (Barth 1963, p. 507) and, although there are propositional statements in Scripture, they are fallible human pointers to revelation-in-encounter. Michael Horton explains Barth’s idea of revelation:

For Barth, the Word of God (i.e., the event of God’s self-revelation) is always a new work, a free decision of God that cannot be bound to a creaturely form of mediation, including Scripture. This Word never belongs to history but is always an eternal event that confronts us in our contemporary existence. (Horton 2011, p. 128)

In his book Encountering Scripture: A Scientist Explores the Bible, one of the leading theistic evolutionists of today, John Polkinghorne, explains his view of Scripture:

I believe that the nature of divine revelation is not the mysterious transmission of infallible propositions . . . but the record of persons and events through which the divine will and nature have been most transparently made known . . . The Word of God uttered to humanity is not a written text but a life lived . . . Scripture contains witness to the incarnate Word, but it is not the Word himself. (Polkinghorne 2010, pp. 1, 3)

Like Sparks, Polkinghorne seems to be following Barth in his view of the inspiration of Scripture (misrepresenting the orthodox view in the process), which is opposed to the idea of revelation to divinely accredited messengers (the prophets and apostles). Therefore, in his view the Bible is not God’s Word but is only a witness to it with revelation seen as an event rather than the written Word of God (propositional truth statements). In other words, the Bible is a flawed record of God’s revelation to human beings, but it is not revelation itself. This view is not based on anything within the Bible, but is based upon extra-biblical, philosophical, critical grounds with which Polkinghorne is comfortable. Unfortunately, Polkinghorne offers a straw-man argument regarding the inspiration of Scripture as being “divinely dictated” (Polkinghorne 2010, p. 1). For him, the idea of the Bible being inerrant is “inappropriately idolatrous” (Polkinghorne 2010, p. 9), and so he believes he has a right to judge Scripture with his own autonomous intellect.

However, contra Barth and Polkinghorne, the Bible is not merely a record of

events, but also gives us God’s interpretation of the meaning and significance

of the events. We do not only have the gospel, but we also have the epistles

which interpret the significance of the events of the gospel for us propositionally.

This can be seen, for example, in the event of the crucifixion of Christ. At

the time of Jesus’s ministry, the high priest Caiaphas saw the event of the

death of Jesus as a historical expedient in that it was necessary for the good

of the nation for one man to die (John 18:14). Meanwhile the Roman centurion

standing underneath the cross came to believe that Jesus was “truly was the

Son of God

” (Mark 15:39). Yet, Caiaphas and the Centurion could not have known

apart from divine revelation that the death of Christ was ultimately an atoning

sacrifice made to satisfy the demands of God’s justice (Romans 3:25). We need

more than an event in the Bible, we must also have the revelation of the meaning

of the event or the meaning simply becomes subjective. God has given us the

meaning and significance of these events through His chosen medium of the prophets

and the apostles.

Furthermore, the charge of biblical docetism (that it denies the true humanity of Scripture), moves too quickly in presuming genuine humanity necessitates error:

Given an understanding of the Spirit’s work that superintends the production of the text without bypassing the human author’s personality, mind or will, and given that truth can be expressed perspectivally—that is, we do not need to know everything or to speak from a position of absolute objectivity or neutrality in order to speak truly—what exactly would be doecetic about an infallible text should we be given one? (Thompson 2008, p. 195)

What is more, the adage “to err is human” is simply assumed to be true. It may be true that humans err but it is not true that it is intrinsic for humanity to necessarily always err. There are many things we can do as humans and not err (examinations for example) and we must remember God created humanity at the beginning of creation as sinless and therefore with the capacity not to err. Also, the incarnation of Jesus Christ shows sin, and therefore error, not to be normal. Jesus

who is impeccable was made in the likeness of sinful flesh, but being in “fashion as a man” still “holy harmless and undefiled.” To err is human is a false statement. (Culver 2006, p. 500)

One could argue that both Barth’s and Sparks’s view of Scripture is in fact “Arian” (denial of the true deity of Christ). What is more, Sparks’s contention that God is inerrant but accommodates Himself through human authors (which is where the errors in Scripture come from), fails to see that if what he says is true, then it is also possible that the biblical authors were in error in stating that God is inerrant. How in their erroneous humanity then would they know God is inerrant unless He revealed it to them?

Furthermore, orthodox Christianity does not deny the true humanity of Scripture;

rather it properly recognizes that to be human does not necessarily entail error,

and that the Holy Spirit kept the biblical writers from making errors they might

otherwise have made. The assertion of a mechanical view of inspiration (God

dictates the words to human authors) is simply a canard. Rather, orthodox Christianity

embraces a theory of organic inspiration. “That is, God sanctifies the natural

gifts, personalities, histories, languages, and cultural inheritance of the

biblical writers” (Horton 2011, p. 163). The orthodox view of the inspiration

of Scripture, as opposed to the neoorthodox view, is that revelation comes from

God in and through words. In 2 Peter 1:21 we are told

that: “for prophecy never came by the will of man, but

holy men of God spoke as they were moved by the Holy Spirit.

” Prophecy was

not motivated by man’s will in that it did not come from human impulse. Peter

tells us how the prophets were able to speak from God by the fact that they

were being continually “moved” (pheromenoi, present passive participle)

by the Holy Spirit as they spoke or wrote. The Holy Spirit moved the human authors

of Scripture in such a way that they were moved not by their own “will” but

by the Holy Spirit. This does not mean that human authors of Scripture were

automatons; they were active rather than passive in the process of writing Scripture,

as can be seen in their style of writing and the vocabulary they used. The role

of the Holy Spirit was to teach the authors of Scripture (John 14:26; 16:12–15). In the New Testament it was the apostles or those closely

associated with them whom the Spirit led to write truth and overcome their

human tendency to err. The apostles shared Jesus’s view of Scripture, presenting

their message as God’s Word (1 Thessalonians 2:13) and proclaiming that it was

“not in words which man’s wisdom teaches but which the Holy Spirit teaches

”

(1 Corinthians 2:13). Revelation then did not come about within the apostle

or prophet, but it has its source in the Triune God (2 Peter 1:21). The relationship

between the inspiration of the biblical text through the Holy Spirit and human

authorship is too intimate to allow for errors in the text, as New Testament

scholar S. M. Baugh demonstrates from the book of Hebrews:

God speaks to us directly and personally (Heb. 1:1–2) in promises (12:26) and comfort (13:5) with divine testimony (10:15) to and through the great “cloud of witnesses” of OT revelation . . . In Scripture, the Father speaks to the Son (1:5–6; 5:5), the Son to the Father (2:11–12; 10:5) and the Holy Spirit to us (3:7; 10:15–16). This speaking of God in the words of Scripture has the character of testimony which has been legally validated (2:1–4; so Greek bebaios in v. 2) which one ignores to his peril (4:12–13; 12:25). This immediate identification of the biblical text with God’s speech (cf. Gal. 3:8, 22) is hard to jibe with the reputed feebleness of the biblical authors. (Baugh 2008)

In the same way Jesus can assume our full humanity without sin so it is that God can speak through the fully human words of prophets and apostles without error. The major problem with seeing Scripture as erroneous is summed up by Robert Reymond:

We must not forget that the only reliable source of knowledge that we have of Christ is the Holy Scripture. If the Scripture is erroneous anywhere, then we have no assurance that it is inerrantly truthful in what it teaches about him. And if we have no reliable information about him, then it is precarious indeed to worship the Christ of Scripture, since we may be entertaining an erroneous representation of Christ and thus may be committing idolatry. (Reymond 1996, p. 72)

Jesus’s View of Scripture

If Jesus’s acceptance and teaching of the reliability and truthfulness of Scripture

were false, then this would mean that He was a false teacher and not to be trusted

in the things He taught. Jesus clearly believed, however, that Scripture was

God’s Word and therefore truth (John 17:17). In John 17:17, notice that Jesus

says: “Sanctify them by Your truth. Your word is truth

.” He did not say that

“your word is true” (adjective), rather He says “your word is truth” (noun).

The implication is that Scripture does not just happen to be true; rather the

very nature of Scripture is truth, and it is the very standard of truth to which

everything else must be tested and compared. Similarly, in John 10:35 Jesus

declared that “Scripture cannot be broken

” the “term ‘broken’ . . . means that

Scripture cannot be emptied of its force by being shown to be erroneous” (Morris

1995, p. 468). Jesus was telling the Jewish leaders that the authority of Scripture

could not be denied. Jesus’s own view of the Scripture was that of verbal inspiration,

which can be seen from His statement in Matthew 5:18:

For assuredly, I say to you, till heaven and earth pass away, one jot or one tittle will by no means pass from the law till all is fulfilled.

For Jesus, Scripture is not merely inspired in its general ideas or its broad claims or in its general meaning, but is inspired down to its very words. Jesus settled many theological disputes with His contemporaries by a single word. In Luke 20:37–38 Jesus “exploits an absent verb in the Old Testament passage” (Bock 1994, p. 327) to argue that God continues to be the God of Abraham. His argument presupposes the reliability of the words recorded in the book of Exodus 3:2–6). Furthermore, in Matthew 4, Jesus’s response to being tempted by Satan was to quote sections of Scripture from Deuteronomy (8:3; 6:13, 16) demonstrating His belief in the final authority of the Old Testament. Jesus overcame Satan’s temptations by quoting Scripture to him “It is written . . .” which has the force of or is equivalent to “that settles it”; and Jesus understood that the Word of God was sufficient for this.

Jesus’s use of Scripture was authoritative and infallible (Matthew 5:17–20; John 10:34–35) as He spoke with the authority of God the Father (John 5:30; 8:28). Jesus taught that the Scriptures testify about Him (John 5:39), and He showed their fulfilment in the sight of the people of Israel (Luke 4:17–21). He even declared to His disciples that what is written in the prophets about the Son of Man will be fulfilled (Luke 18:31). Furthermore, He placed the importance of the fulfillment of the prophetic Scriptures over escaping His own death (Matthew 26:53–56). After His death and resurrection He told His disciples that everything that was written about Him in Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms must be fulfilled (Luke 24:44–47), and rebuked them for not believing all that the prophets have spoken concerning Him (Luke 24:25–27). The question then is how could Jesus fulfill all that the Old Testament spoke about Him if it is filled with error?

Jesus also regarded the Old Testament’s historicity as impeccable, accurate, and reliable. He often chose for illustrations in his teaching the very persons and events that are the least acceptable today to critical scholars. This can be seen from his reference to: Adam (Matthew 19:4–5), Abel (Matthew 23:35), Noah (Matthew 24:37–39), Abraham (John 8:39–41, 56–58), Lot and Sodom and Gomorrah (Luke 17:28–32). If Sodom and Gomorrah were fictional accounts, then how could they serve as a warning for future judgement? This also applies to Jesus’s understanding of Jonah (Matthew 12:39–41). Jesus did not see Jonah as a myth or legend; the meaning of the passage would lose its force, if it was. How could Jesus’s death and resurrection serve as a sign, if the events of Jonah did not take place? Furthermore, Jesus says that the men of Nineveh will stand at the last judgement because they repented at the preaching of Jonah, but if the account of Jonah is a myth or symbolic, then how can the men of Nineveh stand at the last judgement?

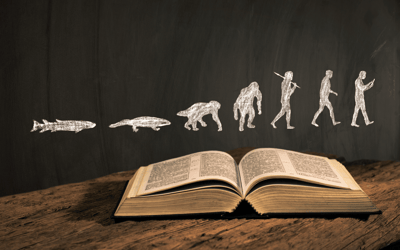

Fig. 1. Jesus’s view of the creation of man at the beginning of creation is directly opposed to the evolutionary timeline of the age of the earth.

Moreover, there are multiple passages in the New Testament where Jesus quotes

from the early chapters of Genesis in a straightforward, historical manner.

Matthew 19:4–6 is especially significant as Jesus quotes from both Genesis 1:27 and Genesis 2:24. Jesus’s use of Scripture here is authoritative in settling

a dispute over the question of divorce, as it is grounded in the creation of

the first marriage and the purpose thereof (Malachi 2:14–15). The passage is

also striking in understanding Jesus’s use of Scripture as He attributes the

words spoken as coming from the Creator (Matthew 19:4). More importantly, there

is no indication in the passage that He understood it figuratively or as an

allegory. If Christ were mistaken about the account of creation and its importance

to marriage, then why should He be trusted when it comes to other aspects of

His teaching? Furthermore, in a parallel passage in Mark 10:6 Jesus said, “‘But

from the beginning of creation, God ‘made them male and female’.

” The statement

“from the beginning of creation” (‘άπό άρχñς κτíσεως;’—see John 8:44; 1 John 3:8, where “from the beginning” refers to the beginning of creation) is a reference

to the beginning of creation and not simply to the beginning of the human race

(Mortenson 2009, pp. 318–325). Jesus was saying that Adam and Eve were there

at the beginning of creation, on Day Six, not billions of years after the beginning

(fig. 1).

In Luke 11:49–51 Jesus states:

Therefore the wisdom of God also said, “I will send them prophets and apostles, and some of them they will kill and persecute,” that the blood of all the prophets which was shed from the foundation of the world may be required of this generation, from the blood of Abel to the blood of Zechariah who perished between the altar and the temple. Yes, I say to you, it shall be required of this generation.

The phrase “from the foundation of the world

” is also used in Hebrews 4:3,

where it tells us God’s creation “works were finished from the foundation of

the world.

” However, verse 4 says that “God rested on the seventh day from all

His works.

” Mortenson points out:

The two statements are clearly synonymous: God finished and rested at the same time. This implies that the seventh day (when God finished creating, Gen. 2:1–3) was the end of the foundation period. So, the foundation does not refer simply to the first moment or first day of creation week, but the whole week. (Mortenson 2009, p. 323)

Jesus clearly understood that Abel lived at the foundation of the world. This means that as the parents of Abel, Adam and Eve, must also have been historical. Jesus also spoke of the devil as being a murderer “from the beginning” (John 8:44). It is clear that Jesus accepted the book of Genesis as historical and reliable. Jesus also made a strong connection between Moses’s teaching and his own (John 5:45–47) and Moses made some very astounding claims about six-day creation in the Ten Commandments, which He says were penned by God’s own hand (Exodus 20:9–11 and Exodus 31:18).

To question the basic historical authenticity and integrity of Genesis 1–11 is to assault the integrity of Christ’s own teaching. (Reymond 1996, p. 118)

Moreover, if Jesus was wrong about Genesis, then He could be wrong about anything,

and none of His teaching would have any authority. The importance of all this

is summed up by Jesus in declaring that if someone did not believe in Moses

and the prophets (the Old Testament) then they would not believe God on the

basis of a miraculous resurrection (Luke 16:31). Those who make the charge that

the Scriptures contain error find themselves in the same position as the Sadducees

who were rebuked by Jesus in Matthew 22:29: “Jesus answered and said to them,

‘You are mistaken, not knowing the Scriptures nor the power of God’.

” The implication

by Jesus here is that the Scriptures themselves do not err, as they speak accurately

concerning history and theology (in context the Patriarchs and the resurrection).

The apostle Paul issued a warning to the Corinthian Church:

But I fear, lest somehow, as the serpent deceived Eve by his craftiness, so your minds may be corrupted from the simplicity that is in Christ.(2 Corinthians 11:3).

Satan’s method of deception with Eve was to get her to question God’s Word (Genesis 3:1). Unfortunately, many scholars and Christian lay people today are falling for this deception and are questioning the authority of God’s Word. We must remember, however, that Paul exhorts us that we are to have “the mind” (1 Corinthians 2:16) and “attitude” of Christ (Philippians 2:5). Therefore, as Christians, whatever Jesus’s belief was concerning the truthfulness of Scripture should be what we believe; and He clearly believed that Scripture was the perfect Word of God and, therefore, truth (Matthew 5:18; John 10:35; 17:17).

Jesus as Saviour and the Implications of His Teaching being False

The fatal flaw in the idea that Jesus’s teaching contained error is that, if Jesus in His humanity claimed to know more or less than He actually did, then such a claim would have profound ethical and theological implications (Sproul 2003, p. 185) concerning Jesus’s claims of being the truth (John 14:6), speaking the truth (John 8:45), and bearing witness to the truth (John 18:37). The critical point in all of this is that Jesus did not have to be omniscient to save us from our sins, but He certainly had to be sinless, which includes never telling a falsehood.

Scripture is clear is that Jesus was sinless in the life he lived, keeping God’s law perfectly (Luke 4:13; John 8:29; 15:10; 2 Corinthians 5:21; Hebrews 4:15; 1 Peter 2:22; 1 John 3:5). Jesus was confident in His challenge to His opponents to convict Him of sin (John 8:46), but His opponents were unable to answer His challenge; and even Pilate found no guilt in him (John 18:38). The belief that Jesus was truly human and yet sinless has been a universal conviction of the Christian church (Osterhaven 2001, p. 1109). However, did Christ’s true humanity require sinfulness?

The answer to that must be no. Just as Adam, when created, was fully human and yet sinless, so the second Adam who took Adam’s place not only started his life without sin but continued to do so. (Letham 1993, p. 114)

Whereas Adam failed in his temptation by the Devil (Genesis 3), Christ succeeded in His temptation, fulfilling what Adam had failed to do (Matthew 4: 1–10). Strictly speaking, the question of whether Christ was able to sin or not (impeccability)

means not merely that Christ could avoid sinning, and did actually avoid it, but also that is was impossible for Him to sin because of the essential bond between the human and the divine natures. (Berkhof 1959, p. 318)

If Jesus in his teaching had pretended or proclaimed to have more knowledge

than he actually had, then this would have been sinful. The Bible tells us that

“we who teach will be judged more strictly

” (James 3:1). Scripture also says

that it would be better for a person to have a millstone hung around his neck

and to be drowned than to lead someone astray (Matthew 18:6). Jesus made statements

such as “I do not speak on my own authority. Rather, it is the Father, living

in me

” (John 14:10) and “I am . . . the truth

” (John 14:6). Now if Jesus claimed

to teach these things and then taught erroneous information (for example, regarding

Creation, the Flood, or the age of the earth), then His claims would be falsified,

He would be sinning, and this would disqualify Him from being our Saviour. The

falsehood He would be teaching is that He knows something that He actually does

not know. Once Jesus makes the astonishing claim to be speaking the truth, He

had better not be teaching mistakes. In His human nature, because Jesus was

sinless, and as such the “fullness of the Deity

” dwelt in Him (Colossians 2:9),

then everything Jesus taught was true; and one of the things that Jesus taught

was that the Old Testament Scripture was God’s Word (truth) and, therefore,

so was His teaching on creation.

When it comes to Jesus’s view on creation, if we claim Him to be Lord, then what He believed should be extremely important to us. How can we have a different view than the one who is our Saviour as well as our Creator! If Jesus was wrong concerning His views on creation, then we can argue that maybe He was wrong in other areas too—which is what is being argued by scholars such as Peter Enns and Kenton Sparks.

Conclusion

One of the reasons today for believing that Jesus erred in His teaching is driven by a desire to syncretize evolutionary thinking with the Bible. In our own day, it has become customary for theistic evolutionists to reinterpret the Bible in light of modern scientific theory. However, this always ends in disaster because syncretism is based on a type of synthesis—blending together the theory of naturalism with historic Christianity, which is antithetical to naturalism.

The issue for Christians is what one has to concede theologically in order to hold to a belief in evolution. Many theistic evolutionists inconsistently reject the supernatural creation of the world, yet nevertheless accept the reality of the virgin birth, the miracles of Christ, the resurrection of Christ, and the divine inspiration of Scripture. However, these are all equally at odds with secular interpretations of science. Theistic evolutionists have to tie themselves up in knots in order to ignore the obvious implications of what they believe. The term “blessed inconsistency” should be applied here, as many Christians who believe in evolution do not take it to its logical conclusions. However, some do, as can be seen from those that affirm Christ and the authors of Scripture erred in matters of what they taught and wrote.

People say they do not accept the Bible’s account of origins in Genesis when

it speaks of God creating supernaturally in six consecutive days and destroying

the world in a global catastrophic flood. This cannot be said, however, without

overlooking the clear teaching of our Lord Jesus on the matter (Mark 10:6; Matthew 24:37–39) and the clear testimony of Scripture (Genesis 1:1–2; 3:6–9; Exodus 20:11; 2 Peter 3:3–6), which He affirmed as truth (Matthew 5:17–18; John 10:25; 17:17). Jesus said to His own disciples that those who receives you [accepting the apostles’ teaching] receives me

(Matthew 10:40). If we confess Jesus is our Lord, we must be willing to submit to Him as the teacher of the Church.

References

Archer, G. L. 1982. New international encyclopedia of Bible difficulties. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

Barth, K. 1963. Church dogmatics: The doctrine of the Word of God. Vol. 1. Part 2. Edinburgh, Scotland: T&T Clark.

Baugh. S. M. 2008. Book review: God’s Word in human words. Retrieved from http://www.reformation21.org/shelf-life/review-gods-word-in-human-words.php on July 12, 2013.

Beale, G. K. 2008. The erosion of inerrancy in evangelicalism: Responding to new challenges to biblical authority. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway.

Behm, J 1967. μορφή. In Theological dictionary of the New Testament, ed. G. Kittel. Vol. 4. Grand Rapids, Michigan: W. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Berkhof, L. 1958. Systematic theology. Edinburgh: Scotland: Banner of Truth.

Bock, D. L. 1994. Luke: The IVP New Testament commentary series. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press.

Carson, D. A. 1991. The Gospel according to John. (The Pillar New Testament Commentary). Grand Rapids, Michigan: W. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Culver, R. D. 2006. Systematic theology: Biblical and historical. Fearn, Ross-Shire: Christian Focus Publications Ltd.

Enns, P. 2012. The evolution of Adam: What the Bible does and doesn’t say about human origins. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Brazos Press.

Fee, G. D. 1995. Paul’s letter to the Philippians: The New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: W. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

Hansen, G. W. 2009. The letter to the Philippians: The pillar New Testament commentary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: W. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

Horton, M. 2011. The Christian faith: A systematic theology for pilgrims on the way. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

Keener, C. S. 2003. The gospel of John: A commentary. Vol. 1. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers.

Kostenberger, A. J. 2004. John: Baker exegetical commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker.

Ladd, G. E. 1994. A theology of the New Testament. Rev. D. A. Hagner. Cambridge, United Kingdom: The Lutterworth Press.

Letham, R. 1993. The work of Christ: Contours of Christian theology. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press.

Marshall, I. H. 1976. The origins of the New Testament christology. Downers Grove: Illinois: InterVarsity Press.

McGrath, A. E. 2011. Christian theology: An introduction. 5th ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing Limited.

Morris, L. 1995. The gospel according to John: The new international commentary on the New Testament. Rev. ed. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans.

Mortenson, T. 2009. Jesus’ view of the age of the earth. In Coming to grips with Genesis: Biblical authority and the age of the earth, ed. T Mortenson and T. H. Ury. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Osterhaven, M. E. 2001. Sinlessness of Christ. In Evangelical dictionary of theology, ed. W. Elwell. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic.

Packer, J. I. 1958. “Fundamentalism” and the Word of God. Grand Rapids, Michigan: W. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

Polkinghorne, J. 2010. Encountering Scripture: A scientist explores the Bible. London, England: SPCK.

Reymond, R. L. 1998. A new systematic theology of the Christian faith. 2nd ed. Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson.

Silva, M. 2005. Philippians: Baker exegetical commentary on the New Testament. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academics.

Sparks, K. L. 2008. God’s Word in human words: An evangelical appropriation of critical biblical scholarship. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic.

Sparks, K. 2010. After inerrancy, evangelicals and the Bible in the postmodern age. Part 4. Retrieved from http://biologos.org/uploads/static-content/sparks_scholarly_essay.pdf on October 10, 2012.

Sproul, R. C. 1996. How can a person have a divine nature and a human nature at the same time in the way that we believe Jesus Christ did? Retrieved from http://www.ligonier.org/learn/qas/how-can-person-have-divine-nature-and-humannature on August 10, 2012.

Sproul, R. C. 2003. Defending your faith: An introduction to apologetics. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books.

Strong, A. H. 1907. Systematic theology: The doctrine of man. Vol. 2. Valley Forge, Pennsylvania: Judson Press.

Thayer, J. H. 2007. Thayer’s Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament. 8th ed. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers.

Thomasius, G., I. A. Dorner, and A. E. Biedermann. 1965. God and incarnation in mid-nineteenth century German theology (A library of protestant thought). Trans. and ed. C. Welch. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, M. D. 2008. Witness to the Word: On Barth’s doctrine of Scripture. In Engaging with Barth: Contemporary evangelical critiques, ed. D. Gibson and D. Strange. Nottingham, United Kingdom: Apollos.

Ware, B. 2013. The humanity of Jesus Christ. Retrieved from http://www.biblicaltraining.org/library/humanity-jesuschrist/systematic-theology-ii/bruce-ware on June 12, 2013.

Wenham, J. 1994. Christ and the Bible. 3rd ed. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers.