Research conducted by Answers in Genesis staff scientists or sponsored by Answers in Genesis is funded solely by supporters’ donations.

Abstract

Considerable disagreement exists in the church about what God made on the second day of Creation Week in Genesis 1. Should it be called “the firmament” or “the expanse”? Was the firmament or expanse the earth’s atmosphere where the birds and clouds are? Or was it a hard, metal-like dome or vault over the atmosphere under which or in which the sun, moon, and stars were placed? Were the “waters above” clouds, or did they form a vapor canopy above the atmosphere that collapsed at the beginning of Noah’s flood? Or is the expanse what we today call outer space and the “waters above” are the outer boundary of the universe? This essay will examine carefully the Hebrew words in the relevant biblical texts, the various English translations of the key phrases in Genesis 1, the Septuagint Greek translation of the same in Genesis 1, a number of popular commentaries on these verses, and some images related to these questions found in the Logos Bible software. The conclusion of this study is that 1) the expanse is outer space, 2) where the birds fly and the clouds float is the “face of the expanse,” and 3) the “waters above” are the outer boundary of the universe.

Keywords: raqiya‘, expanse, firmament, heavens, sky, waters above, waters below, atmosphere, vault, dome, canopy, flat earth, Bible translations, commentaries, Logos Bible software.

Many Christians today have assumed that the firmament (or expanse) created on Day 2 of Creation Week is the atmosphere where the birds fly and the clouds float. Many young-earth creationists (no doubt in part because of the influence of the writings of Henry Morris and John Whitcomb) also think that “the waters above” the firmament are a watery canopy (made of vapor, liquid, or ice) in the upper atmosphere which collapsed at the onset of Noah’s Flood to produce the many days of rain.1 On the other hand, some commentators as well as flat-earth advocates say that the firmament was a hard, metal-like shell covering the atmosphere and attached to the perimeter of a circular, flat earth.

However, as I argue below, a careful examination of the biblical text (and especially the Hebrew words in a few key phrases in Genesis 1) does not support these various interpretations. Rather I will give my reasons for concluding that the firmament/expanse (Hebrew: רָקִיעַ [raqiya‘]) is primarily what we call “outer space,” the atmosphere is the “face of” of the raqiya‘, and the waters above are at the outer boundary of the universe. In this I am concurring with and supplementing the view of the firmament (or expanse) advocated by Russell Humphreys, Danny Faulkner, Andrew Kulikovsky, and William Barrick mentioned below.

The Meaning of the English “Sky”

Before we look at the Hebrew words in the biblical text, it is helpful to consider what we mean by the English word “sky.” The online Oxford Dictionary in the UK says it is, “the region of the atmosphere and outer space seen from the earth.” 2 The online Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines it this way: “the upper atmosphere or expanse of space that constitutes an apparent great vault or arch over the earth.” 3 Dictionary.com is helpfully more precise by giving three definitions:

- The region of the clouds or the upper air; the upper atmosphere of the earth.

- The heavens or firmament, appearing as a great arch or vault.

- The supernal or celestial heaven.4

From my experience, I would say that during day-light hours most people think of the earth’s atmosphere when they hear the word “sky.” At night-time, they would normally think of what we often call “outer space” where the sun, moon, and stars are located. Of course, astronomers also think and talk about the sky this way. So, it is an imprecise word, just as is the Hebrew word for “heaven” (shamayim), which refers to the domain of birds (e.g., Genesis 9:2), the domain of the sun, moon, and stars (e.g., Genesis 26:4) and the abode of God (Psalm 2:4). Like most words in every language, we cannot be certain what a word means or refers to until that word is used in a specific context: a phrase, a sentence, or longer text. So now we need to turn our attention to the Hebrew word behind the translations of “firmament” and “expanse.”

The Meaning of raqiya‘

The words “firmament” and “expanse” in English translations are renderings of the Hebrew word (raqiya‘).5 The noun, raqiya‘, is related to the verb, raqa‘). This verb is used eleven times in the Old Testament and is translated variously in the ESV (and similarly in other translations) as “hammer,” “spread out,” “beat,” “stamp,” or “overlay.” Often it refers to spreading, beating, or hammering a thin layer of metal (gold or silver or bronze) onto an object.6 God is said to have “spread out” the heavens and “spread out” the earth.7 The verb is used in the phrase “stamp your feet” (along with the phrase “clap your hands”) in the sense of making noise.8 David poetically refers to pulverizing his enemies and “stamping them as the mire of the streets.” 9

What about the translations of raqiya‘ as either “expanse” or “firmament”? Both ideas of spreading and hardness might be implied by the Hebrew verb raqa‘.

Some who favor “expanse” point out that many verses speak of God “stretching out” or “spreading out” the heavens, using four different Hebrew verbs, including raqa‘. Russell Humphreys cites these 17 examples: 2 Samuel 22:10; Job 9:8, 26:7, and 37:18; Psalm 18:9, 104:2, and 144:5; Isaiah 40:22, 42:5, 44:24, 45:12, 48:13, and 51:13; Jeremiah 10:12 and 51:15; Ezekiel 1:22; and Zechariah 12:1 (Humphreys 1994, 66). If those verses refer to the raqiya‘ (the word is not used in those verses), then “expanse” would be the best translation. But then we could ask some questions. Did God make the raqiya‘ on Day 2 and then stretch it on Day 2 or on Day 4? Or is it still being stretched? Is this biblical evidence of the expansion of the universe, as modern cosmologists imagine? On the other hand, given that most the verses that speak of this “stretching” of the heavens are in poetic texts, 10 where figurative language is common and where the text often also says that the earth was spread out, are we mistaken to take these statements as literal to be incorporated into our thinking about the raqiya‘ made in Genesis 1? I would not want to be dogmatic about any of these views of the “stretching of the heavens.” The verses are not clear enough, in my mind.

As noted above, the translation “firmament” comes from the Latin Vulgate translation, which used firmamentum, reflecting the Greek word stereôma used in the Septuagint. While the Hebrew raqa‘ is sometimes used to refer to hammering metal, Danny Faulkner helpfully points out that we must be careful to distinguish between the verbal action and the object receiving the verbal action (Faulkner 2019, 281–285). Raqa‘ is used with respect to gold, which is a soft metal, but also with bronze, which is much harder. You can use a hammer to beat or spread out a rock or a banana. The verbal action does not determine the meaning of the noun or tell you anything about the object’s physical characteristics. Raqa‘ is never used together with raqiya‘. (i.e., the Bible never says that the raqiya‘ was spread out or hammered). We also cannot assume a meaning of the noun (especially the physical shape, dimensions, material substance, or location of the raqiya‘) simply from one of the various meanings of related verb.

We can see the same in our own language. In English, “hammered” does not reveal the shape or material nature of a carpenter’s hammer, and “stamped” does not tell you what a postage stamp looks like or what it is made of. When used with abstract objects, the verbs have a very different meaning, for example in, “He tried to hammer home his main point by raising his voice.” Or, “Her commitment to excellence was stamped all over the school she founded.” Context is key.

Therefore, the meaning of the noun, raqiya‘, especially regarding its physical characteristics, must be determined by the context in which it is used. So “firmament” does not seem to be the right translation.

The meanings of the verb raqa‘ have led some scholars to think that the biblical writers were teaching that the raqiya‘ was a solid dome over a flat earth, an idea (those scholars assert) that is similar to how other ancient peoples around Israel viewed the world. A growing number of “flat earth” proponents today have a similar view of the raqiya‘. At the end of this article we will come back to that view of the raqiya‘ and the earth.

The Use of raqiya‘ in Genesis 1

On Day 2 of Creation Week God created raqiya‘. Which of the English translations, “firmament” or “expanse,” is best? What is it and where is it located? To understand what God made here, we need to look carefully at the use of this word in Genesis 1 as well as its use in the rest of the Old Testament.

In the New King James Version (NKJV) of Genesis 1:6–8 we read (“firmament” is the translation of raqiya‘ in each case):

6Then God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.” 7Thus God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament; and it was so. 8And God called the firmament Heaven. So the evening and the morning were the second day.

So, the raqiya‘ separated the waters (made on Day 1) into the “waters above” the raqiya‘ and the “waters below” the raqiya‘. God called this raqiya‘ “heaven” (Hebrew: שָׁמַיִם, shamayim), which being plural in form can also be translated “heavens.” However, the context here demands the singular “heaven,” because the Hebrew word, raqiya‘, is singular and is referring to one space between the two regions of water.

The next time the word raqiya‘ appears is on Day 4 of Creation Week. Genesis 1:14–18 (NKJV) reads:

14Then God said, “Let there be lights in the firmament of the heavens to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs and seasons, and for days and years; 15and let them be for lights in the firmament of the heavens to give light on the earth”; and it was so. 16Then God made two great lights: the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night. He made the stars also. 17God set them in the firmament of the heavens to give light on the earth, 18and to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness. And God saw that it was good.

The phrase containing the word raqiya‘ appears three times on Day 4.

1:14, in the firmament of the heavens (בִּרְקִ֣יעַ הַשָּׁמַ֔יִם, birqiya‘ hashshamayim)

1:15, in the firmament of the heavens (birqiya‘ hashshamayim)

1:16, in the firmament of the heavens (birqiya‘ hashshamayim)

Here on Day 4, God says three times that the sun, moon, and stars are in the raqiya‘. Verse 17 says that He set (or placed or put) them in the raqiya‘. The repetition must surely be seen as emphatic. God wants us to know that these heavenly luminaries are not above or under but in the raqiya‘. In these three verses, the Hebrew preposition attached to raqiya‘ is ב (“b”), which is translated here as “in” and is its primary meaning when used as a preposition,especially when referring to a place or space (Brown, Driver, and Briggs 1996, 88).11

The last time that raqiya‘ is used in Genesis 1 is on Day 5 after God creates the birds. And here most of our English translations confuse the reader through lack of precision. Genesis 1:20 (NKJV) says:

Then God said, “Let the waters abound with an abundance of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the face of the firmament of the heavens.”

The key phrase for this discussion is at the end of this verse and highlighted in bold above. The Hebrew behind this translation is:

עַל־פְּנֵ֖י רְקִ֥יעַ הַשָּׁמָֽיִם al penê reqia‘ hashshamayim‘

We need to look very carefully at this phrase because it is significantly different from what we find in Genesis 1:14–17.

Various Bible Translations of Genesis 1:20

Most English translations do not render the Hebrew phrase literally at this point in Genesis 1:20. Only the NKJV translates the phrase literally. Consider how several popular English translations render this phrase at the end of the verse.

King James Version (KJV) says:

And God said, “Let the waters bring forth abundantly the moving creature that hath life, and fowl that may fly above the earth in the open firmament of heaven.”

New American Standard Bible (NASB, 1995) has:

Then God said, “Let the waters teem with swarms of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth in the open expanse of the heavens.”

English Standard Version (ESV) gets closer with the correct preposition but does not translate penê (“face”), as it does in Genesis 1:2:

And God said, “Let the waters swarm with swarms of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the expanse of the heavens.”

Christian Standard Bible (CSB) likewise gets the preposition correct but translates using “sky” and also does not translate penê (“face”), as it does in Genesis 1:2:

Then God said, “Let the water swarm with living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the expanse of the sky.”

New English Translation (NET) agrees with the CSB:

God said, “Let the water swarm with swarms of living creatures and let birds fly above the earth across the expanse of the sky.”

New International Version (NIV1984) agrees with the CSB and the NET:

And God said, “Let the water teem with living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the expanse of the sky.”

New International Version (NIV2011) introduces more confusion by changing “expanse” in the 1984 version to the ambiguous word “vault”:

And God said, “Let the water teem with living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the vault of the sky.”

New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) uses another ambiguous word, “dome,”:

And God said, “Let the waters bring forth swarms of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the dome of the sky.”

New Living Translation (NLT), unsurprisingly, offers a very non-literal rendering, by changing the subject from “birds” to “skies,” changing the verb form to passive, and using a very different preposition:

Then God said, “Let the waters swarm with fish and other life. Let the skies be filled with birds of every kind.”

In contrast, the NKJV renders Genesis 1:20 as:

Then God said, “Let the waters abound with an abundance of living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the face of the firmament of the heavens.”

Note that the NKJV is the only one of the English translations above that reflects the difference in the prepositions used in the raqiya‘ phrases in 1:14–17 and 1:20, and translates the noun penê with the noun “[the] face [of].”12 All the other translations fail to reflect the presence of penê ([the] face [of]) in the verse.

Although most of the translations above render al as “across,” that is a rare meaning in the 5,864 times it is used in the Old Testament. Its most common meanings are “upon/on” or “above.” It also has the meaning of “in front of.” Of course, “upon” and “on” have essentially the same meaning. As will be clear below, “above” does not fit the context of Genesis 1 regarding the raqiya‘ (although it is appropriately translated as “above” in v. 20 with respect to the earth). The meaning “in front of” could be a valid meaning in Genesis 1:20. The preposition al never means “in.”13 This is quite different from the preposition “in” (b) in the phrases (birqiya‘ hashshamayim) involving the raqiya‘ on Day 4 (Genesis 1:14, 15, and 17).

The next word in the phrase near the end of Genesis 1:20 is penê, which although a plural word is often translated in the Old Testament as “face” or “surface,”14 as in Genesis 1:2 (twice) and elsewhere in Genesis and the rest of the Old Testament.15 So, for example, in Genesis 1:2 we find these phrases or something very similar in most English translations:

“darkness was on the face of the deep” (‘al penê tehôm)

“the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters” (‘al penê hamayim)

Notice, the darkness was on (or over) the face (or surface) of the earth-covering ocean. The darkness was not said to be in the ocean but on the surface of it. Likewise, the Spirit was hovering over (or on) the face (or surface) of the waters, not in the waters. The text is clear, as all the English translations agree.

As we have seen, this phrase ‘al penê is used in Genesis 1:20, where it literally says that the birds are flying across (or on or over) the face of the expanse of the heavens. Also, in this verse there is no Hebrew adjective behind the English word “open,” as we find in some of the English translations. The wording “in the open expanse” is an interpretation that is not clearly supported by the Hebrew in this context. In other words, the text of Genesis 1:20 (in Hebrew) does not say that the birds are flying in the expanse (or firmament). It is hard to even conceive of what “open expanse” or “open firmament” would mean here.

This phrase ‘al penê also is used in Genesis 1:29, 6:1, 7:3, 7:18, 7:23, and 8:9, where it refers to land animals and birds living on the surface (or face) of the earth. The phrase is also used in Genesis 11:4, 8 and 9 and in Genesis 41:56, where it refers to people being scattered over or living on the face (or surface) of the earth (not in the earth).

It should be noted that in Genesis 1:2, the following translations (like the NKJV) render ‘al penê as “upon/over the face/surface of”: NASB1995, ESV, NIV1984, NRSV, NET, and KJV. The NIV2011 says the darkness is “over the surface of” the deep, but the Spirit is moving “over” the waters.

Similarly, all these translations render ‘al penê in Genesis 1:29 as “upon/on the face/surface” of the earth: NKJV, NASB1995, ESV, NIV1984, NIV2011, NRSV, NET Bible, and KJV.

These translations all translate this Hebrew phrase the same way in Genesis 6:1 (except for the NIV1984 and NIV2011, which translate the phrase simply as “on”), Genesis 7:3 (except for the NIV1984 and NIV2011, which translate ‘al penê as “throughout”), Genesis 7:18, Genesis 7:23, Genesis 11:4, and Genesis 11:8-9 (except that in v.8 the NIV1984 and NIV2011 translate ‘al penê simply as “over”).

So, all these English translations render ‘al penê essentially the same literal way (equivalent to “on the face of” or “over the face of”) in all these cases in Genesis except in Genesis 1:20, where nearly all of them translate ‘al as “across” and only the NKJV reflects the noun penê with the translation “[the] face [of]”.

The phrase ‘al penê is sometimes translated in a non-literal way in other places in Genesis (and elsewhere). For example, in the ESV of Genesis 11:28 it is translated as “in the presence of.” In 18:16 and 19:28 it is rendered “toward” and in 25:18 it is translated once as “opposite” and once as “over against.” But in these cases, the context shows that the phrase is used in an idiomatic sense, so that a non-literal, translation is preferred. But the context of Genesis 1 does not support such a non-literal translation in 1:20, given the phrase’s connection to the raqiya‘, although even these non-literal senses convey some distance and do not imply the notion of “in the raqiya‘.”

Septuagint: Ancient Greek Translation of Genesis 1:20

The Septuagint is the Greek translation of the Old Testament. It is so named because supposedly the Pentateuch (the first five books, written by Moses) was translated by about 70 Jewish scholars in Egypt in about 270BC.16 The Septuagint is therefore often referred to simply as the LXX (the Roman number for 70). The LXX translates this phrase (‘al penê reqia hashshamayim) in Genesis 1:20 as: κατὰ τὸ στερέωμα τοῦ οὐρανοῦ (kata to stereôma tou ouranou).17 This Greek phrase can be translated as “along (or over or through or upon) or in” the firmament of the heaven (Bauer, Arndt, and Gingrich 1979, 406). The word stereôma has the sense of firmness, which likely influenced Jerome in his Latin Vulgate to translate raqiya‘ as firmamentum, from which we get the English word “firmament.”

The LXX translators used the Greek preposition kata to translate the Hebrew al penê. But kata actually does not reflect the presence of the word penê and corresponds in meaning only to the Hebrew preposition al.

However, in Genesis 1:2 the LXX translators rendered ‘al penê as ἐπάνω (which means above, upon, or over [the abyss or the water]).18 In Genesis 6:1,19 7:3, and 7:18 they translated ‘al penê as simply ἐπί (i.e., on or upon [the earth]). But in Genesis 11:4 and 11:9 they rendered ‘al penê as ἐπί προσώπου (i.e., on or upon the face of [all the earth]).

So, the LXX translators were inconsistent in their rendering of this Hebrew phrase into Greek in these different verses in Genesis, though contextually it means the same in each case.

The Use of raqiya‘ in the Rest of the Old Testament

The noun raqiya‘ is used 17 times in the Old Testament. In Genesis 1 it is used on Day 2 (Genesis 1:6, 7 [3×], and 8), Day 4 (Genesis 1:14, 15, and 17), and Day 5 (Genesis 1:20). The only other places that this noun is used in the Old Testament are in Ezekiel 1:22–26 (4×) and 10:1, in Psalm 19:1 and 150:1, and in Daniel 12:3.

The two passages in Ezekiel are referring to two heavenly visions that Ezekiel saw about 14 months apart in which he describes things that are something like, or that resemble, parts of things or certain qualities of things that he was familiar with in life. But he is clearly not describing any physical being or object he saw, or we see, on earth, in the sky or in outer space. And what was under the raqiya‘ (wings, v.23) and above the raqiya‘ (a throne, v. 26) are completely different from the description of the raqiya‘ in Genesis 1:6–8. So, it would be a very erroneous interpretation to try to use the vision that Ezekiel saw to understand the nature, location, and relationship of the raqiya‘ with respect to other physical things in the time-space-matter world described on Days 2, 4, and 5 of Creation Week.

The parallelism of the two phrases in Psalm 19:1 (“The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament shows His handiwork.” [NKJV]) and the context of the next five verses in this psalm clearly indicate that in this case the raqiya‘ is referring to what we call outer space, where the sun and stars are (not simply the atmosphere, where the birds fly, which are not mentioned in this psalm).

Psalm 150:1 does not say where the raqiya‘ is, but does call it “his mighty expanse/firmament” (e.g., ESV/NKJV) or “firmament of His power” (KJV), a fitting description of outer space where the sun, moon, and stars are, as the previous psalm indicates, but not so appropriate to describe the atmosphere of the earth where birds fly.

In Daniel 12:3 the apparently parallel phrases in the verse (“like the brightness of the firmament” and “like the stars” [NKJV]) suggests that the raqiya‘ is where the stars are. It speaks of the brightness of the expanse, clearly referring to light, but the verse tells us nothing about the hardness of the raqiya‘.

Psalm 148 is a psalm of praise to God. Verses 1–6 focus on praise “from the heavens” (v. 1). Verses 7–14 focus on praise “from the earth” (v.7). The psalm does not use the word raqiya‘ in verses 1–6. But four times it uses shamayim (“heavens,” in v.1 and v.4 [3×—”highest heavens” is literally “heavens of heavens”]). Verses 1–4 (ESV) say,

1 Praise the Lord! Praise the Lord from the heavens; praise him in the heights!

2 Praise him, all his angels; praise him, all his hosts!

3 Praise him, sun and moon, praise him, all you shining stars!

4 Praise him, you highest heavens, and you waters above the heavens!

Notice that waters “above the heavens” are mentioned in the context of where the sun, moon, and stars are located. The birds are not mentioned (v. 10) until after the psalmist has moved his attention away from the heavens and down to the earth (v. 7). Notice also that after verse 7, we have the mention of hail, snow and clouds (v. 8). Those waters in solid and gaseous form surely are not the waters above the heavens referred to in verse 4. Furthermore, the psalmist indicates that the waters “above the heavens” are still there at the time he is writing. In fact, verse 6 says that all the things mentioned in the previous verses, which God created, “shall not pass away.” This further reinforces the conclusion that the waters above the heavens are still there, even today.

All this supports the conclusion that if the raqiya‘ is the area of our universe where the sun, moon, and stars are (what we call outer space) then “the waters above” the raqiya‘ are at the outer boundary of the universe. We will return to that idea later. But next let us consider what a number of commentaries say about the raqiya‘ and the waters above the raqiya‘.

What Do Commentaries Say about the raqiya‘ in Genesis 1?

Many Genesis commentaries by biblical scholars say nothing about the raqiya‘ prepositional phrases under our consideration in Genesis 1:14–17 and 1:20. Some simply assert that the raqiya‘ is “the sky,” and usually the context indicates that in the interpreter’s mind this is the earth’s atmosphere. But they give little or no exegetical argument in defense of that translation. Consider these commentaries, most of which are by eminent Hebrew scholars.

Umberto Cassuto (1961)

Cassuto was one of the most respected Jewish Old Testament commentators of the twentieth century. Several of the evangelical commentators below follow his explanation.

In discussing Day 2, he uses the meaning of the verb raqa‘ (“to be hammered out”) and quotes part of Exodus 39:3 (“and they did hammer out gold leaf”) to say that the firmament (raqiya‘) “signifies a kind of horizontal area, extending through the very heart of the mass of waters.” He then says, “How the space between heaven and earth was formed we are not told here explicitly; nor are the attempts of the commentators to elucidate the matter satisfactory” (31).

How the hammering of very thin gold leaf relates to the “space” is not explained. But he goes on to say that this raqiya‘ “is none other than what we designate heaven” and “is the site of the heavens as we know it” (31). But Cassuto does not explain what he means by using the singular “heaven” and the plural “heavens” here, so this is unclear.

Soon after its creation, he says, the raqiya‘ “began to rise in the middle, arching like a vault the upper waters resting on top of it.” However, Cassuto cites no textual support for this “rising” and “arching.” Beneath this arched vault, he says, “stretches the expanse of lower waters, that is, the waters of the vast sea, which still covers all the heavy, solid matter below” (31–32). So, the firmament seems to be, in Cassuto’s view, the atmosphere: an arching, vaulted space holding up the upper waters and separating them from the lower water covering the earth.

On Day 4 he says nothing about the raqiya‘ phrase as he instead focuses on other words in Genesis 1:14–18.

On Day 5 he translates verse 20 as “. . . and let flying creatures fly above the earth / in front of the firmament of the heaven.” He says,

In front of (literally, ‘on the face of’) the firmament of the heavens. The attempts that have been made to explain this phrase are not satisfactory. It seems to reflect the impression that a person receives on looking upward; the creatures that fly about above one’s head appear then to be set against the background of the sky—in front of the firmament of the heavens. (49, italics in the original)

His attempt to explain the raqiya‘ using the words “heaven,” “heavens” and “vault” does not seem satisfactory either. Also, he now seems to introduce another space between the firmament and the waters below it, a space where the birds fly.

Claus Westermann (1984)

In his translation of all of Genesis 1, this prominent liberal, German scholar translates the three raqiya‘ phrases in 1:14–17 as “in the vault of the heavens.” In 1:20 he has “let birds fly over the earth across the vault of the heavens,” which does not reflect the presence of penê (face) in the Hebrew phrase.

In commenting on Day 2, he says that from the meaning of the related verb raqa‘, the raqiya‘ is a “hammered out,” and “solid” vault (117).

He spends nine pages discussing words used to describe Day 4 but says nothing about the uses of raqiya‘.

When he comes to Day 5, he renders the end of verse 20 as “let the birds fly above (ַעל) the earth, across (ַעל) the firmament of the heavens.” He then adds,

It is very difficult for us to render the preposition here as it has such a broad scope; what is intended is, over the earth and under the vault of heaven. Hebrew had to use some such roundabout expression because it had no word for space or atmosphere, where the air was, but only for air in motion. (137)

But, as I noted in his translation of Genesis 1 (77), his rendering and interpretation of verse 20 focuses on the preposition (ַעל) but overlooks the presence פְּנֵ֖י (of as in “across the face of the firmament”). Leaving out an important word certainly does make it more difficult to interpret the text.

R. Kent Hughes (2004)

In discussing Day 2, Hughes follows Cassuto in saying that the raqiya‘ is a “horizontal area extending through the very heart of the mass of water and dividing it into two layers.” He adds that “it was the visible expanse of sky with the waters of the sea below and the clouds holding water above. It is the blue we see.” He says Genesis 1:6–8 is a phenomenological description of the “earth’s atmosphere as viewed from earth” (28).

On Days 4 and 5, he says nothing about the uses of raqiya‘. But he does describe the solar system as “a jeweled watch in the midst of the universe,” which also contains the stars (32). So, in his view, the solar system and stars are apparently not in the raqiya‘ (which he has already equated with the atmosphere of the earth), in contrast to what God says three times in Genesis 1, namely, that the sun, moon, and stars are in the raqiya‘.

Gordon Wenham (1987)

Wenham asserts that on Day 2 the raqiya‘ “occupies the space between the earth’s surface and the clouds.” But he quickly adds “Quite how the OT conceives the nature of the firmament is less clear” (19). He refers to the verbal root, raqa‘, and two verses that use that verb to mean stamping, spreading, and hammering. Then he cites Job 37:18 saying that “it speaks of the skies being ‘spread out hard as a molten mirror’” (20). But we should note that the verse does not use raqiya‘ or shamayim (heaven/sky) but shechaqim, which in about two thirds of its 21 uses in the Old Testament is translated as “clouds” or clearly in context refers to the clouds.20 So, it is not at all certain that the verse is describing the raqiya‘ created on Day 2. Furthermore, the verse contains the words spoken by Elihu (whose speech begins in 36:1), not by God. God certainly appears to give overall approval of Elihu’s comments in that God did not rebuke him or require a sacrifice for him, as God did in the case of Job’s other three counselors: Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar. But God nowhere affirms that everything Elihu said was accurate. So, we can’t use Job 37:18 to say that God is telling something about the nature of the raqiya‘ that He made on Day 2.

Wenham continues in this paragraph, “Ezek 1:22 and Dan 12:3 describe the firmament as shiny. Such comments may suggest that the firmament was viewed as a glass dome over the earth.” But he then backs away from the suggestion by saying that “since the most vivid descriptions occur in poetic texts, the language may be figurative” (20). However, as I remarked earlier, it is quite unsound to use what Ezekiel saw in a heavenly vision, that is loaded with symbolism, to determine the location or nature of the real physical raqiya‘ made on Day 2. Daniel 12:3 says of the wise: “those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the sky [raqiya‘] above. . . . like the stars.” The Hebrew verb translated as “shine” is זָהַר (zahar) and the Hebrew word for “brightness” is the related noun, זֹ֣הַר (zohar). In neither case do the words suggest that the raqiya‘ is like a glassy dome. The stars shine as points of light, not like a shiny metal.

In remarks on Day 4, he has no discussion of the raqiya‘ phrases (21–23). When discussing Genesis 1:20 his only comment reflects the presence of the preposition “al” (ַעל) but omits “the face of” (פְּנֵ֖י) when he says, “‘Across the firmament.’ From the ground, birds appear to fly against the background of the sky. This is one of the indications in the narrative that it is written from the perspective of a human observer” (24). So, it is not clear if he thinks the birds are in the raqiya‘ or in front of it.

John H. Sailhamer (1990)

Commenting on Day 2, he says the raqiya‘ refers “not only to the place where God put the sun, moon, and stars (v. 14) but also the place where the birds fly (v. 20: ‘across the expanse of the sky’)” (p. 29). This puts the birds and the sun, moon, and stars together in the same place. He says it is “unlikely” that the raqiya‘ is a solid partition or vault that separates the earth from the waters above. Rather, it is “more likely” that what is in view is “something within the everyday experience of the natural world, in a general way, that place where the birds fly and where God placed the lights of the heaven.” He adds that “the ‘waters above’ the sky is likely a reference to the clouds” (29). On Days 4 and 5 he says nothing about the raqiya‘ prepositional phrases.

In Sailhamer (1996), he simply asserts (without any reference to the raqiya‘ phrases), “In Genesis 1, the word ‘sky’ (shamayim), by itself, refers to the open space above the land. It is that realm which contains the clouds, the sun, moon, and stars. It was also the place where the birds fly (see Genesis 1:20)” (55).

Later in a chapter discussing Day 2, he correctly says that raqiya‘ “is used to refer to the place where God put the sun, moon, and stars (1:14)” (116). But then, even though he literally translates the raqiya‘ phrase in 1:20 the same way that the NKJV does, his comment does not reflect the difference between “in the expanse” and “across the face of the expanse” when he says: “It also refers to the place where the birds fly; in Genesis 1:20 we are told that the birds are to fly ‘upon the surface of the expanse of the sky’” (116). Again, this seems to put the birds in the same place as the heavenly luminaries. The waters above the raqiya‘, he says, “are simply the clouds which provide rain for those dwelling in the land.” (117). So, this seems to put the sun, moon, and stars between the clouds and the earth.

In the chapters on Day 4 and Day 5 he makes no comment on the raqiya‘ phrases.

Allen P. Ross (1998)

Holding to a modified form of the gap theory, Ross says that the six literal days of Genesis 1 were days of “recreation,” “God’s first act of redemption,” after the “chaos” which resulted from the judgment on the rebellion associated with Satan (74–75, 105, 107). This interpretation of Genesis 1 which has creation (v.1) followed by judgment to produce a chaos (v.2) followed by redemption in (vv. 3–31), is fatally flawed.21

Regarding Day 2, he says, “On the second day God created an expanse in the atmosphere to separate the waters above from the waters below” (109). This suggests that the atmosphere (in which God created the expanse) already existed from the time of the chaos, for he says concerning “this atmospheric expanse” that:

Up to this point the atmosphere may have been like a dense fog; there may have been very little visibility and very little light shining through. With the creation of the expanse God thus set a division between the cloud masses above and the waters below. (109)

But Genesis 1 says nothing about clouds and certainly nothing about dense fog, and verses 6–8 say nothing about increasing visibility on Day 2 so that light made on Day 1 can shine through to the surface of the earth.

When he comes to Genesis 1:14–19, Ross contradicts the clear statements of the text when he says,

The fourth day records how God created the luminaries—the sun, moon, and stars—to rule over the heavens. The language here describes the phenomena; the sun is not in the atmosphere—it is far beyond it—but appears to be in the heavens. Likewise, it is possible to interpret the passage with the meaning that the sun, moon, and stars now appeared for the first time, not that they were only now brought into existence. (110–111, italics in the original)

But three times these verses say that the heavenly bodies are in the raqiya‘. And nowhere in these verses does it say that they appeared to be in the heavens. Moses could have easily said that on Day 4, if that was the case, because he used the Hebrew verb תֵרָאֶ֖ה (tera’eh, meaning “appear”) in Genesis 1:9.

Now we know, and I think the ancient Israelites figured out, that the sun is not in the atmosphere of the earth. But Ross said earlier (109) that the raqiya‘ was placed in the preexisting atmosphere. So, if the raqiya‘ is in the atmosphere and if the sun is in the raqiya‘ (as God plainly declares three times on the Day 4 concerning the sun), then the sun is in the atmosphere which contains the raqiya‘. Also, Ross gives no arguments (from the English or the Hebrew text) to support his assertion that the heavenly bodies were created earlier and only appeared on Day 4. Unfortunately, like so many others, Ross offers no discussion of the raqiya‘ phrases on Day 4 and Day 5. Because of his a priori commitment to the gap theory, he apparently saw no need to do so.

C.F. Keil and F. Delitzsch (1986)

On Day 2, based on the verbal root, raqa‘, they interpret the raqiya‘ to be “the spreading out of the air, which surrounds the earth as an atmosphere” (52) and the waters above the raqiya‘ to be “not the ethereal waters beyond the limits of the terrestrial atmosphere, but the waters which float in the atmosphere, . . ., the waters which accumulate in clouds and then . . . pour down as rain” (53–54).

On Day 4, they say that the heavenly lights “were created by God and placed in the firmament” (57). But although they clearly take the days of creation as “simple earthly days,” and not as years or thousands of years (51), they reason that the “primary material” of the earth and the sun, moon, and stars were made in Genesis 1:1. They say the creation of the heavenly lights

was completed on the fourth day, just as the creative formation of our globe was finished on the third; that the creation of the heavenly bodies therefore proceeded side by side, and probably by similar states with that of the earth so that the heaven with its stars was completed on the fourth day. (59)

But Genesis 1:1 explicitly says God made the earth. This verse does not say that He made the sun, moon, and stars at the same time. To read that view into the text requires equating “heaven” with those heavenly objects (which they are not) and having them in existence before God made the raqiya‘. But God explicitly says (Genesis 1:17) that He placed those heavenly lights in the raqiya‘ on Day 4. Furthermore, if God started to make the sun, moon, and stars in Genesis 1:1 (what such partially-made objects would be is anyone’s guess) and only completed making them on Day 4, then He had a perfectly good Hebrew verb to use. He used כָלּהָ (kalah, meaning finished or completed) twice in Genesis 2:1–2. Instead, on Day 4 He said, “let there be” (1:14) and “God made” (1:16) just as on Day 2 He said, “let there be” (1:6) and “God made” (1:7), using the exact same Hebrew words. So, Genesis says that sun, moon, and stars were made on Day 4, just as He made the raqiya‘ on Day 2 and He made the light on Day 1.

On Day 5, they translate verse 20 to read “. . . let birds fly above the earth in the face (the front, i.e., the side turned towards the earth) of the firmament,” which is close to the view I am advocating. But they make no further comment about the raqiya‘ phrase.

Andrew E. Steinmann (2019)

Regarding Day 2, Steinmann connects raqa‘ to the verb raqa‘ meaning “stretch out” or “spread out,” citing Psalm 136:6, Isaiah 42:5 and 44:24, and Job 37:18. He then says that “the expanse is the sky with the upper waters—the clouds—and the waters below the sky—the sea” (53). Clearly, he is taking the raqiya‘ to mean the earth’s atmosphere.

In commenting on Day 4 he says the two greater lights and the stars are “in the earth’s sky,” but gives no explanation of what he means by “earth’s sky” (54). He makes no other comment related to the raqiya‘ phrases on Day 4 or on Day 5.

C. John Collins (2006)

In discussing the raqiya‘ made on Day 2, Collins relies on the meaning of the verb raqa‘ (to beat out or to spread out) and the words of the nineteenth century German scholar, Franz Delitzsch, to say that the expanse “conveys the idea of the atmosphere ‘as the semi-spherical vault of heaven stretched over the earth and its water’.” He adds that this is “a prime example of phenomenological description, that is, things are described as they appear, and not ‘scientifically’” (footnote 23 on pages 45–46, italics are his). He continues that this is “clearly not a description of a ‘vapor canopy’ or cloud cover” (his italics) as, he thinks, can be seen from the use of raqiya‘ in Psalm 19:1 and Daniel 12:3. Furthermore he says that, “in Genesis 1:8 God names the extended surface ‘sky,’ with which we are familiar.”

He says nothing about the raqiya‘ in his commentary about Day 4 and Day 5 (47–48). Nor does he say anything about it a few pages later when he adds additional comments about Day 4 (56–58). In his last reference to the raqiya‘ (in chapter 10, entitled “Genesis 1–4, History, and Science”), he says that there is “no evidence” that the raqiya‘ “must be describing a solid canopy as a physical entity; it is enough to take it as speaking as if the sky were such” (264, italics are his). But if there is no evidence that the raqiya‘ was being described as a solid canopy (as I agree), why should we treat the text as if that is the case?

Later in the book he returns with some brief comments about raqiya‘. Again, he argues against the idea that the “waters above” were a canopy above the atmosphere. He quotes Franz Delitzsch’s 1888 commentary and agrees with him that the raqiya‘ is the atmosphere of the sky, a semi-spherical vault of heaven stretched over the earth and its waters. Collins adds, “The sky looks like that is what happened” (264). But is it reasonable to assume that ancient Israelites looked at either the night sky or the day-time sky and thought, “It looks like a semi-spherical vault was stretched over the earth”? I do not see evidence of such stretching when I look at the sky any time of the day. Collins does not say what observations he makes of the sky that lead him to think it looks like that happened in the past. In his comments on this section he also does not discuss the raqiya‘ phrases in Genesis 1:14–17 and 1:20.

John D. Currid (2003)

Regarding Day 2, Currid remarks that “the nature of the firmament is unknown. It appears to be a divider between water in the sky and water upon the earth (i.e., rivers and seas). How the ancient Hebrew may have conceived of this object is also unclear” (65).

But then in the next paragraph he claims that “the Hebrews believed that the raqiya‘ was actually a solid mass, as evidenced by certain biblical passages (Ezek. 1:22–25; 10:1; Dan. 12:3; Ps. 19:1).” He also says that the meaning of the verb raqa‘ supports this idea that the raqiya‘ is a solid mass.

But as I argued above, it is illegitimate to draw any conclusions about the nature of the raqiya‘ in Genesis 1 based on a meaning of the verb raqa‘ and based on the heavenly visions that Ezekiel saw. And the other two passages say nothing about the raqiya‘ being a “solid mass.” Furthermore, the most you could say from these passages is that Ezekiel, Daniel, and David thought the raqiya‘ was solid (though that would not be a valid conclusion). What those three prophets possibly thought is no basis for saying what the ancient Israelites in general believed about the raqiya‘. Nor is this a basis for saying that Moses believed that the raqiya‘ was a solid mass.

Further regarding Day 2, Currid says that the waters under the raqiya‘ “no doubt refers to the oceans, seas and rivers of the earth.” However, on Day 2 there was not yet any dry land and therefore no rivers, and God does not call the waters “seas” until Day 3 (Genesis 1:10). Currid continues,

The expression, “waters which were above,” is more difficult to understand. Many see it as merely figurative language for terrestrial clouds or a water canopy between the earth and the sun. Rather it actually should be taken at face value to mean “a large body of water, a sea, above a solid firmament, which firmament serves as a roof to the universe and under which firmament are the sun, moon and stars.” (64)

Regarding Day 4, he states that God is “filling the spheres of the physical cosmos” and “creates the luminaries to occupy the firmament of the sky: the sun, the moon and the stars” (72). But he says nothing about the raqiya‘ phrases in Genesis 1:14–17 or on Day 5 in Genesis 1:20.

H.C. Leupold (1942)

Leupold believed that the days of creation were literal, 24-hour days and he presented arguments for his rejection of the gap theory (45–46, 53 and 56).

On Day 2, referring to the root verb, raqa‘, he says the raqiya‘ is “the vault or dome of the heavens” or (quoting another scholar) is “that immense gaseous ocean, called the atmosphere, by which the earth is encircled” (59). He continues:

Apparently, before this firmament existed, the earth waters on the surface of the earth and the cloud waters as we now know them were contiguous without an intervening clear air space. It was a situation like a dense fog upon the surface of the waters. Clear vision of all except the very nearest objects must have been impossible. Free activity unhampered by the fog blanket would have been impossible. Man would not have had an appropriate sphere for activity, nor could sunlight have penetrated freely to do its beneficent cheering work. Now the physical laws that cause clouds and keep them suspended go into operation. These clouds constitute the upper waters. (59–60)

Again, there is no mention of clouds or fog in Genesis 1. Nor is there any basis in the text to say that on Day 1 there were both “waters on the surface of the earth” and “cloud waters.” Verse 2 is clear that both darkness was on the surface and the Spirit moved over the surface. There is no textual basis for saying that part of the water was in a global ocean and part was in an atmospheric state (clouds or fog). And verse 3 clearly indicates that the created light reached the surface of the global ocean covering the earth on Day 1.

Commenting on Genesis 1:3, Leupold says that the sun was created on the fourth day (52). But regarding Day 4, he draws an analogy between the earth and the heavens saying:

The earth is created in the rough, subject to certain deficiencies or incompletenesses which are removed one by one through the following days; similarly, the heavens were created in the rough, heavenly bodies in vast spaces, not yet functioning as they shall later. What still remains to be done in and with them is now complete on the fourth day. The sun, moon, and stars were in existence but were not yet doing the work which gets to be theirs in the fourth days’ work. Light was in existence, but now these heavenly bodies come to be the ones that bear this light in themselves. . . . the non-luminous heavenly bodies become bearers of light, and this for the purpose of dividing the day from the night. (71)

But there is no basis in the text for this notion of the two-step development from non-luminous sun, moon, and stars to luminous ones. But we do have explicit statements for the several-step development of the earth to make it ready for the creation of man. Leupold also creates confusion when he says,

The adverbial modifier ‘in the firmament of the heavens’ shows the relation of the fourth days’ work to that of the second. The firmament prepared in advance had to be thus prepared, otherwise the light of these luminaries would have failed to benefit the earth. (72)

But then he says regarding verse 17,

It would be crude interpretation of the opening verb ‘and he put,’ if this were understood to mean that God first fashioned the luminaries in one place and then took them and set or suspended them in the firmament. (76)

However, God says in verse 14 “let there be lights in the expanse” and He says in verse 17 that He “put them in the expanse.” If He created them as non-luminous objects on Day 1, as Leupold asserted, before He made the expanse on Day 2, then in fact, in Leupold’s view, God did make them in one place and moved them to another. Reading a development of the heavenly bodies into the text for which there is no explicit evidence creates problems. The text says that God made the firmament (raqiya‘) on Day 2 and He made the heavenly bodies and placed them in the raqiya‘ on Day 4.

Commenting on Day 5 (78–79), he correctly translates the statement in verse 20 as “let birds fly above the ground across the face of the firmament” and he says, “The firmament is regarded as having a face, that is a side turned toward and, as we say, ‘facing the earth” (78–79). But he fails to connect what he says about the birds and the raqiya‘ on Day 5 with what he says about the raqiya‘ on Day 2 and Day 4.

Henry M. Morris (1976)

On Day 2, Morris says that raqiya‘ means “expanse or spread-out-thinness” though he gives no basis for such definitions. He contends that the firmament “is obviously the atmosphere” (58). In his view it is not a solid dome across the sky, though he does say, “A ‘firmament’ is simply ‘thin, stretched-out space’” (59). He declares that the waters above the firmament “probably constituted a vast blanket of water vapor above the troposphere and possibly above the stratosphere as well, in the high-temperature region now known as the ionosphere and extending far into space” (59). But he says the waters above could not be the clouds of water droplets in our present atmosphere because Genesis says the waters were above the firmament. These waters above the firmament (i.e., the vapor canopy) “were condensed and precipitated in the Flood” and “will apparently be restored in the millennial earth and in the new earth which God will create” (61).

In discussing Day 4, Morris says,

On the second day, [God] made the primeval hydrosphere and atmosphere for the terrestrial sphere. On the third day, He made the earth’s lithosphere and plant biosphere. Finally, on the fourth day, He made the astrosphere, the ‘celestial sphere’ of the stars and planets surrounding and illuminating the terrestrial sphere. . . . The lights were set in “the firmament of heaven,” but this was not the same firmament as formed on the second day. The latter is the “open firmament of heaven” where birds were to fly (verse 20). (65, 66–67)

But Genesis 1 does not say that God made one firmament on Day 2 and then made a different firmament on Day 4.22 Rather it says that He made the firmament on Day 2 and then on Day 4 He made the heavenly bodies and put them in the firmament, which in context must be the firmament of Day 2. Morris was misled on this point by the wording of the KJV which says in verse 20 that the birds fly “in the open firmament of heaven.” When he comments later on the Hebrew, he comes close to the correct view when he says,

birds fly in, literally, the ‘face of the firmament of heaven.’ The word translated ‘open’ in the King James is pene and can carry the meaning ‘face of.’ Thus it is reasonable to understand the phrase ‘firmament of heaven’ in this verse to apply to both the troposphere (the lower region of the atmosphere) and the stratosphere. Birds fly only in the lower region—the ‘face’ of the firmament. (69)

But he overlooked the Hebrew prepositions used with raqiya‘ on Day 4 and Day 5 and in the phrase ‘al penê (used in Genesis 1:2 and 1:20).23

Martin Luther (1958)

Viewing the days of creation as literal, 24-hour periods, Luther takes Genesis 1:3 to mean that on Day 1 God created a light source that was distinct from the sun, moon, and stars which He made on Day 4 (19).

Regarding Day 2, he takes the Hebrew word for heaven, shamayim, which was made on Day 1, “to denote something watery or something that has a watery nature.” He then says that “out of this unformed mist, which He called heaven, God created a beautiful and exquisite heaven, such as it is now, except for its stars and larger luminaries” (23). Connecting raqiya‘ to the meaning of raqa‘, he says, “This unformed mass of mist, which was created on the first day out of nothing, God seizes with the Word and gives the command that it should extend itself outward in the manner of a sphere . . . as the bladder of a pig extends itself outward in circular form when it is inflated” (24).

After a discussion on how the firmament could be both hard and soft and how it moves, he remarks,

He places the firmament in the middle, between the waters. I might readily imagine that the firmament is the uppermost mass of all and that the waters which are in suspension, not over but under the heaven, are the clouds which we observe, so that the waters separated from the waters would be understood as the clouds which are separated from the waters on the earth. But Moses says in plain words that the waters were above and below the firmament. Here I, therefore, take my reason captive and subscribe to the Word even though I do not understand it. (26)

He then discusses what the waters above the firmament might be in the light of the thinking of the philosophers, but concludes, “Rather than give approval to those inept thoughts, I for my part shall confess that I do not understand Moses in this passage” (28). He repeats his confession of ignorance again (31), saying, “I shall readily confess that I do not know what these waters are. Indeed, the ancient teachers of the church paid little attention to these matters, as we see Augustine disregarding astronomy in its entirety.”

In his comments on Days 4 and 5, he says nothing about the raqiya‘ phrases.

John Calvin (1992)

Calvin believed that God created light on Day 1 before the heavenly luminaries on Day 4 (76), and he clearly took the days as literal (78). Regarding Day 2, he said that God provided “an empty space around the circumference of the earth.” He adds,

Moreover, the word רָקִיעַ (rakia,) comprehends not only the whole region of the air, but whatever is open above us: as the word heaven is sometimes understood by the Latins. Thus the arrangement, as well of the heavens as of the lower atmosphere, is called רָקִיעַ (rakia,) without discrimination between them, but sometimes the word signifies both together sometimes one part only. . . . (79)

Calvin then says that the Latin firmamentum comes from the influence of the Greek word, stereoma, used in the LXX and that because Psalm 104:2 speaks of God stretching out the heaven like a curtain, raqiya‘ “literally means expanse.” With the conviction that Genesis is “the book of the unlearned,” he continues:

Moses describes the special use of this expanse, to divide the waters from the waters from which word arises a great difficulty. For it appears opposed to common sense, and quite incredible, that there should be waters above the heaven. Hence some resort to allegory and philosophize concerning angels; but quite beside the purpose. For, to my mind, this is a certain principle, that nothing is here treated of but the visible form of the world. He who would learn astronomy, and other recondite arts, let him go elsewhere. Here the Spirit of God would teach all men without exception;. . . . (79–80)

I know of no young-earth creationist who would disagree with Calvin here. Genesis 1 was indeed not written to teach astronomy and other recondite arts. But it does say something about objects which astronomers study. So, there is not a complete disconnect between Genesis and astronomy. In light of his reasoning above, Calvin concludes,

that the waters here meant are such as the rude and unlearned may perceive. The assertion of some, that they embrace by faith what they have read concerning the waters above the heavens, notwithstanding their ignorance respecting them, is not in accordance with the design of Moses. And truly a longer inquiry into a matter open and manifest is superfluous. (80)

He then briefly discusses two verses in the Psalms that refer to the clouds and rain and says,

We see that the clouds suspended in the air, which threaten to fall upon our heads, yet leave us space to breathe. . . . Since, therefore, God has created the clouds, and assigned them a region above us, it ought not to be forgotten that they are restrained by the power of God, lest, gushing forth with sudden violence, they should swallow us up: and especially since no other barrier is opposed to them than the liquid and yielding, air, which would easily give way unless this word prevailed, ‘Let there be an expanse between the waters.’

So, Calvin seems to suggest that the clouds in the sky are the waters above the expanse. And he says it is “superfluous” to give any more inquiry into the matter, which explains why in his discussions on Day 4 and Day 5, he says nothing about the raqiya‘.

Regarding Day 4, Calvin says the creation of the sun, moon and stars “institutes a new order in nature” whereby they disperse the light that was before made on Day 1 (83), In discussing these new heavenly lights and their purpose over the next several pages, he repeatedly and correctly says things like, “Moses does not speak with philosophical acuteness on occult mysteries, but relates those things which are everywhere observed, even by the uncultivated, and which are in common use” (84). He says, “Moses wrote in a popular style” unlike the astronomers who “investigate with great labor whatever the sagacity of the human mind can comprehend” (86).

Calvin certainly took the Scriptures as accurate concerning the creation of the heavenly bodies. But he did not note what the Bible says about them with respect to the raqiya‘.

When he comes to Day 5, he gives one paragraph to comment on Genesis 1:20 regarding the creation of birds on that day.

It seems, however, but little consonant with reason, that he declares birds to have proceeded from the waters; and, therefore this is seized upon by captious men as an occasion of calumny. But although there should appear no other reason but that it so pleased God, would it not be becoming in us to acquiesce in his judgment? Why should it not be lawful for him, who created the world out of nothing, to bring forth the birds out of water? And what greater absurdity, I pray, has the origin of birds from the water, than that of the light from darkness? Therefore, let those who so arrogantly assail their Creator, look for the Judge who shall reduce them to nothing. (88)

Calvin’s argument here is interesting in that Genesis 1:20–23 does not say that God brought forth the birds out of water. But he is right that we should believe God’s Word, even if some things in Genesis 1 go against common sense and our everyday experience or are beyond our complete understanding. Calvin did take God’s Word at face value regarding the literal days, the creation of light before the heavenly bodies, the creation of the birds, etc. But he did not look carefully at God’s Word about the raqiya‘.

We are told that the prophets did not understand everything they wrote (1 Peter 1:10–12). Peter said some statements in Paul’s writing are hard to understand (2 Peter 3:16). And yet their words have meaning, even if we cannot completely understand or fully grasp the implications of the words we understand. Also, we can soundly conclude from a careful study of Genesis 6–9 and other relevant Scriptures that the account in Genesis 6–9 is clearly describing a global catastrophic flood at the time of Noah, even though neither the ancient Israelites nor we can fully comprehend the geological effects of it. So also, in the account of God’s supernatural creation work in Genesis 1, it is not surprising that we can understand that God created different kinds of plants and animals to reproduce after their kind, though we don’t fully know what the taxonomic boundaries of each kind are and how genetics relates to that question. Similarly, we understand something about what and where the raqiya‘ is, even though by common sense or observation neither the ancient Israelites nor we have a full understanding of the physical implications of those statements. But, given that every word of Scripture in the original languages is God-breathed (just as Calvin believed), it is surely not “superfluous” to investigate everything Genesis 1 and other Scriptures say about the raqiya‘ and the waters above it.

In Calvin (2009), he says that the firmament is both “sky where the stars are” and “the air” (38). He repeatedly says that the sun, moon and stars are “in the sky” (i.e., the firmament; 38, 59, 68–70), which is what “the astronomers” study (57). On page 77 he says that the birds fly “in the air” which is contrasted with sky [firmament] on page 38.

Jonathan D. Sarfati (2015)

Sarfati only says in reference to Genesis 1:14–17, “This suggests that the rāqîya‘ means the expanse of space that was later filled with the heavenly objects” (150). He gives no reasons for this interpretation. But he does follow this with an extended argument (151–154) that the raqiya‘ is not a solid dome over the earth.

Andrew S. Kulikovsky (2009)

Although not a commentary, this book takes a more in-depth look at the text than many of the commentaries above. Regarding Day 2, after citing a number of commentators (many of whom I discussed above) who take the raqiya‘ to be the earth’s atmosphere, Kulikovsky says (inserting the Hebrew text and transliteration of the words he italicizes),

The expanse cannot be equated with the atmosphere, since verse 14 states that the sun, moon and stars are set in the expanse and verse 20 states that the birds and other flying creatures are to fly ‘over the surface of the expanse of the heavens’ rather than ‘in the expanse’. (130)

He then gives a helpful refutation of the view that the author of Genesis and other ancient Israelites understood the expanse to be a solid dome over-arching the earth (130–131).

He concludes, particularly because of Genesis 1:14, that the expanse is interstellar space, where the sun, moon, and stars are located, and he suggests that the waters above are still there at the outer boundary of space based on Psalm 148:4. Surprisingly, he says “the waters below the expanse, on the other hand, appear to have become the foundations of the earth—its core and mantle” (132). However, that cannot be correct for Genesis 1:10 tells us that on Day 3 the waters below the expanse became the seas, and 1:22 says that on Day 5 the swimming creatures filled the seas.

Regarding Day 4, he argues against the view (held by Hugh Ross and others) that the sun, moon, and stars were made on Day 1 and only appeared on Day 4. Kulikovsky points out that if that were the case, God had a perfectly good word to use in verse 9, when He said, “let the dry land appear.” In this regard, Kulikovsky also argues (134–135) against Sailhamer’s view about verse 14 which I discussed above.

In his discussion of Day 5, he points out (as I have shown above) that many English translations do a poor job of translating the raqiya‘ phrase in 1:20 about where the birds fly. As he quotes the Hebrew phrase with transliteration, he concludes that the birds fly over the face of the expanse of the heavens (that is, inside the earth’s atmosphere), rather than in the expanse itself (137).

Summary comments about these commentaries

As I studied these commentaries, it was truly remarkable that most of the commentators (most of whom are Hebrew scholars), who declare what the raqiya‘ is and where it is located, have not paid careful attention to all the verses in Genesis 1 and elsewhere in the Old Testament that use that word. Many of them believe that every word of Scripture is inspired by God, but for some reason they did not deal carefully with the words He moved Moses to write about the raqiya‘, sun, moon, stars, and birds.

Also, many of these commentaries say that the clouds in the atmosphere are the “waters above” the raqiya‘. But is it even remotely possible that the Israelites thought the sun, moon, and stars were closer to us than the clouds? All of human experience shows us (and would have shown them) that the clouds block our view of the sun, moon, and stars, not vice versa. So, the clouds cannot be the “waters above” the sun, moon, and stars.

Furthermore, we should ask why so many of these commentators take God’s Word literally (at face value) regarding why God made the heavenly bodies (to give light on earth and to enable man to tell time), but they do not take at face value what God says regarding how He created them (supernaturally by His spoken command, not by natural processes over millions of years; cf. Psalm 33:6–9) and when He created them (on the fourth literal day of history—after He made the earth on Day 1 and all the plants on Day 3). Why is the purpose of the heavenly bodies’ creation taken literally, but the method and timing of their creation are not also taken literally? Of course, for those commentators who accept what the scientific majority says about the history and age of the universe, as most of them above do, they have an unseen problem. If the sun, moon, and stars really are billions of years old, then for most of those years they did not fulfill the function for which God says He created them. So, in this case the Bible would not even be literally correct about God’s purpose in making them.

Many of the commentators above and elsewhere contend that Genesis 1 (or at least the verses about the raqiya‘ ) should be interpreted phenomenologically, that is, as things would have appeared to a human on the earth at the time. But I think this is a mistaken view for several reasons.

Man is not the subject of any verb in Genesis 1, and he doesn’t do anything. God is the one who does everything in Genesis 1. He is the subject of the verbs. He creates and makes. He sees. He speaks to create, and he speaks to bless. And He speaks to explain the purpose of man and what man and animals should eat. So, the chapter is written from God’s perspective, from outside the creation, for seven times it says (using anthropomorphic language), “And God saw.” Furthermore, man was not made until the sixth day, after God had made everything except Eve (but he was asleep when that happened), so the creation events cannot be described as being viewed from the perspective of someone on the earth.

What did the earth look like on Day 1? God could certainly see that the whole earth was covered with water, and there was no dry land. But someone on earth could not see that, especially before God created the light. Although we can understand the words on Day 3, we do not see today in our experience plants coming out of the ground and in one day growing to maturity with fruit on their branches. And we don’t observe sea creatures of all kinds coming into existence in the water where there were no sea creatures previously. We don’t see flying birds coming into existence where there were no birds just seconds before. And we’ve never seen a human being made from the dust of the earth or a woman made from the rib of a man. We can understand what these words mean but we are not getting a human description of the events as a human would observe them. We can only imagine that these creation events were something like what we see in high-speed, time-lapse photography.

So, I conclude that Genesis 1 is written from a divine perspective in words that man could understand (though not in scientifically detailed terms), and we should not interpret the words (particularly the words about the raqiya‘) phenomenologically.

The raqiya‘ and a Flat Earth?

There is a small but growing number of people (some of them professing Christians) all around the world who have tenaciously latched on to the idea of a flat earth. In this view, the earth is a flat, circular disk with a dome placed over the top of the atmosphere in which the birds as well as the sun, moon, and stars exist and move. I think this flat-earth view is not biblically correct, but that is a separate discussion. An excellent resource that presents a biblical and scientific refutation of the claims of flat-earth proponents is by astronomy professor, Danny Faulkner (2019), which has a good section on the raqiya‘ (280–297). It covers some of the points I have made and adds other points about the raqiya‘ as he comes to similar conclusions.

Erroneous statements and diagrams about ancient Israelite beliefs about the raqiya‘

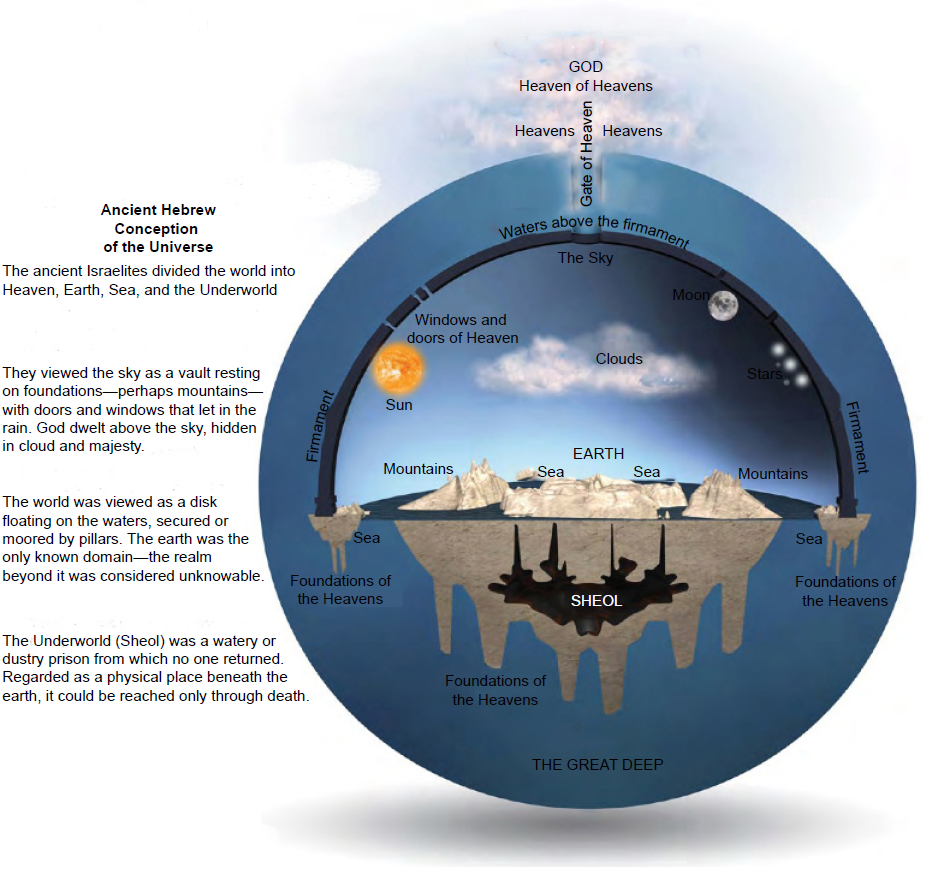

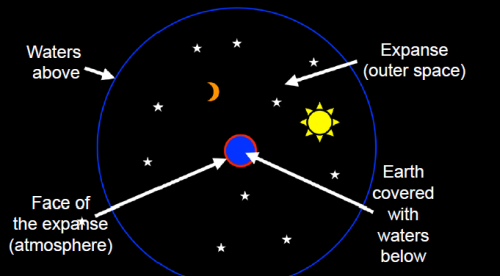

Logos Bible Software has several erroneous statements and pictures about the raqiya‘ (firmament/ expanse) of Genesis 1, which also promote the notion of a flat earth and the idea of the raqiya‘ held by many commentators above. These teach biblically false views about the raqiya‘ and about the ancient Israelites.

The diagram in fig. 1 is declared to express the “Ancient Hebrew Conception of the Universe.” The three longer statements describing the “ancient Hebrew conception” in this graphic are as follows, from top to bottom.

They viewed the sky as a vault resting on foundations—perhaps mountains—with doors and windows that let in the rain. God dwelt above the sky, hidden in cloud and majesty.

The world was viewed as a disk floating on the waters, secured or moored by pillars. The earth was the only known domain—the region beyond it was considered unknowable.

The Underworld (Sheol) was a watery or dusty prison from which no one returned. Regarded as a physical place beneath the earth, it could be reached only through death.

Fig. 1. Supposed ancient Hebrew conception of the universe, taken from Logos Bible Software 8:14, under “Media Resources” for Genesis 1, called “Ancient Hebrew Conception of the Universe” in Faithlife Study Bible Infographics.

As William Barrick has pointed out, there are many reasons to reject the claim that this diagram reflects the view of the ancient Israelites (Barrick 2013, 2016).

Here are several reasons why I also reject this claim about the ancient Israelites. First, we have no way of knowing what the ancient Israelites, especially at the time of Moses when Genesis was written, believed about the earth, the raqiya‘, the heavenly bodies, etc. Apart from Scripture, the Israelites wandering in the wilderness with Moses left no records, and as we have seen from careful attention to the Hebrew words, Genesis 1 certainly does not teach what this diagram depicts.

Second, the Bible itself shows that it is impossible to talk about the “ancient Hebrew conception,” as if all Israelites had the same view. Almost continuously through the Old Testament history, there were faithful Israelites who believed God’s Word and there were idolatrous Israelites who believed and did all kinds of wrong and evil things. John Oswalt, an expert on ancient pagan cultures and literature around the Israelites, has shown that the biblical worldview was “diametrically” opposed to the pagan worldviews of the nations around ancient Israel (Oswalt 2009).24 So there is no good reason to think that they all shared the same picture of the physical arrangement of the heavens and earth. It is also questionable, if not doubtful, that the people in those pagan cultures believed that there literally was a hard vault over the sky as pictured above (Poythress 2019, 171–185). 25

Third, this diagram, like others below, is based on taking certain phrases in the Bible as literal, such as “windows of heaven” and “pillars of the earth,” without any exegetical proofs that such phrases or words should be taken in a woodenly literal manner.26 Even today our scientifically trained weatherman might say that “we can expect it to be raining cats and dogs tomorrow,” and influential citizens are sometimes called “pillars in the community.” But no one takes those statements literally. Idioms are found in the Bible, just as they are in modern languages.

Notice also in fig. 1 that the word “firmament” is outside (and clearly refers to) the hard, black dome, whereas the space under the dome is called “the sky” and is where the sun, moon, and stars are. So, in this case (and similarly in the description and fig. 2), the heavenly bodies are between the firmament (the dome) and the surface of the flat earth, and not in the firmament. Hence diagrams like this have added a space between the firmament and surface of the earth, a space that is not made (or mentioned) in Genesis 1. Yet Genesis 1:14–17 says three times that the heavenly bodies are in the firmament (not under it). Also, in this case, the birds and the sun, moon, and stars are together in the atmosphere. But Genesis 1 clearly says that the sun, moon, and stars are in the firmament and the birds fly across the face of the firmament.

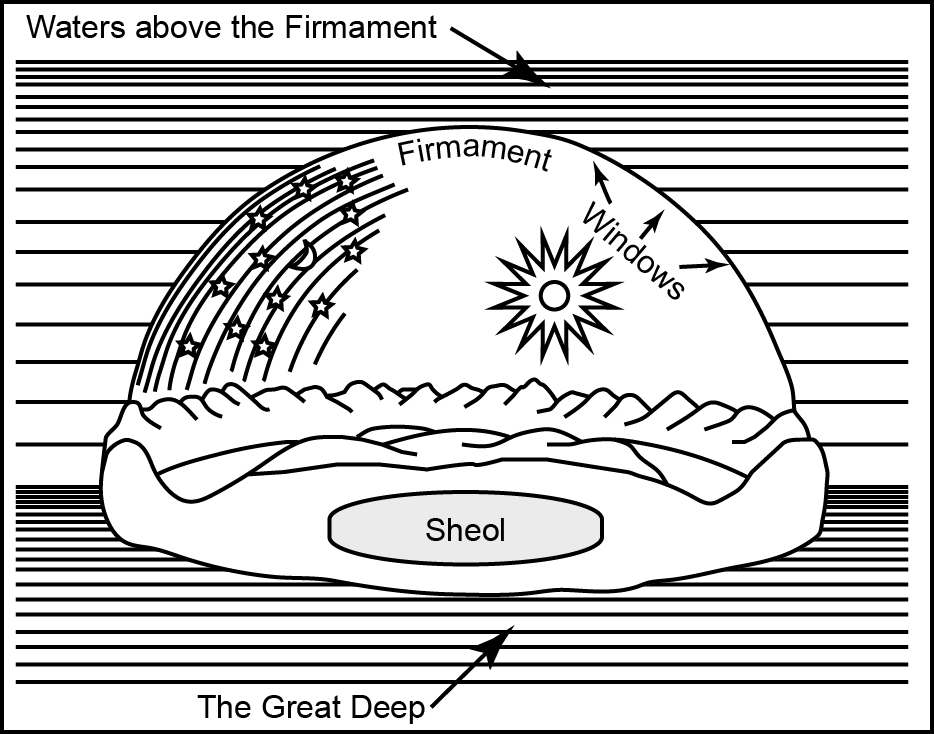

Fig. 2. Supposed ancient Hebrew view of the firmament, taken from Logos Bible Software 8:14, under “Media Resources” for Genesis 1:6, called “Firmament” in Harper’s Bible Dictionary (Rosenberg 1985, 309).

If, on the other hand, such flat-earth proponents say that the sun, moon, and stars are in the firmament (which they take to be a solid dome over the atmosphere), then it is hard to conceive how there can be any movement of the heavenly bodies. Also, they would all appear the same distance from the observer, and we would never see a lunar eclipse.27

Logos Bible Software also contains the following description of the firmament by Joel W. Rosenberg (Associate Professor of Hebrew Literature and Judaic Studies at Tufts University) taken from his article in the Harper’s Bible Dictionary (Rosenberg 1985, 309).

Firmament, God’s division between cosmic waters on the second day of creation (Gen. 1:6–8), forming the sky. One must here imagine a flat earth and a domed expanse of heavens holding back celestial waters from terrestrial. The Hebrew term raqiya‘‘ suggests a thin sheet of beaten metal (cf. Exod. 39:3; Num. 17:3; Jer. 10:9; also Job 37:18). Similar metaphors for sky are found in Homer and Pindar. Job 26:13 depicts God’s breath as the force that calmed (or ‘spread,’ ‘smoothed’ or ‘carpeted’) the heavens. Luminaries were set in the firmament on the fourth day of creation (Gen. 1:14–19). Rains were believed to fall through sluices or windows in its surface (cf. Gen. 7:11). During the Flood, the upper waters joined with the waters of the primordial deep (Heb. tehôm). In more pacific contexts, the firmament, or its pattern of luminaries, is said to declare the praises of God (Ps. 19:1; cf. 150:1). In Ezekiel’s ‘chariot’ vision, a crystal firmament supports the divine throne (Ezek. 1:22, 25, 26), just as something resembling a pavement of lapis lazuli is said to lie at the feet of Yahweh’s throne in Exod. 24:10. Dan. 12:3 alludes to the ‘radiance’ (Heb. zohar) of the firmament. Rabbinic sources regarded the firmament as the chief source of light for heavenly denizens.

But as we have seen, there is no biblical evidence that suggests the noun, raqiya‘, means “a thin sheet of beaten metal.” The verses he cites after that suggestion do not even use the word, raqiya‘. The raqiya‘ of Ezekiel’s vision has nothing to do with the raqiya‘ of Genesis 1. Furthermore, the Bible-believing Christian should not base his or her understanding on what the pagan Homer and Pindar and the spiritually lost Rabbinic sources thought about the raqiya‘ or the sky. I cannot see that Job 26:13 says anything about God calming or spreading the heavens and it certainly does not contain the word raqiya‘.

In the middle of Rosenberg’s statement above, he has a diagram (fig. 2) followed by this caption:

The Hebrew universe. The ancient Hebrews imagined the world as flat and round, covered by the great solid dome of the firmament which was held up by mountain pillars (Job 26:11; 37:18). Above the firmament and under the earth was water, divided by God at creation (Gen. 1:6, 7; cf. Ps. 24:2; 148:4). The upper waters were joined with the waters of the primordial deep during the Flood; the rains were believed to fall through windows in the firmament (Gen. 7:11; 8:2). The sun, moon, and stars moved across or were fixed in the firmament (Gen. 1:14-19; Ps. 19:4, 6). Within the earth lay Sheol, the realm of the dead (Num. 16:30-33; Isa. 14:9, 15). (HBD 309)

But notice above (as in the previous color image) that the firmament is a solid dome with windows and is attached to mountain pillars. But while the description says that “the sun, moon and stars moved across or were fixed in the firmament,” the picture shows them to be in the space between the solid dome firmament and the land and water on the flat earth. And though birds are not shown, the diagram implies that the birds are in the same space as the heavenly bodies, contrary to what Genesis 1 says.

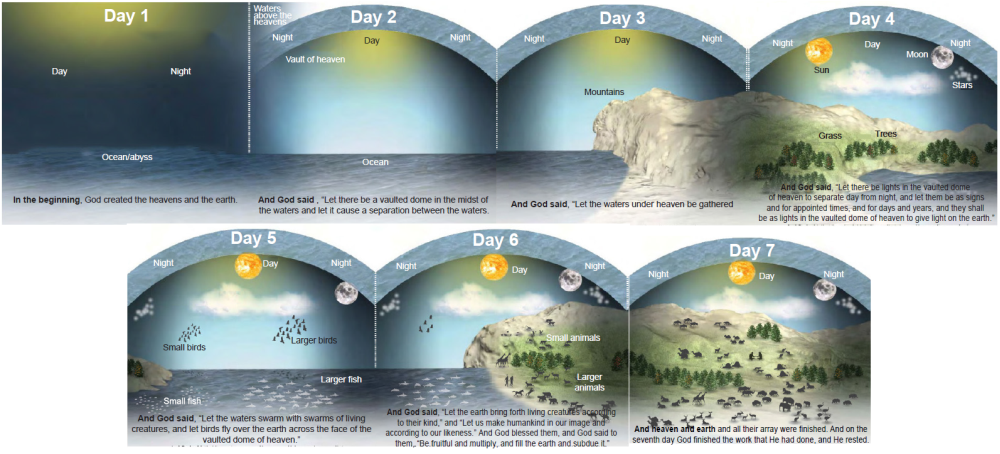

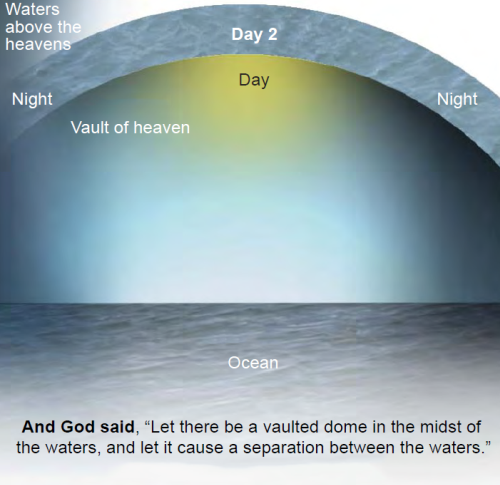

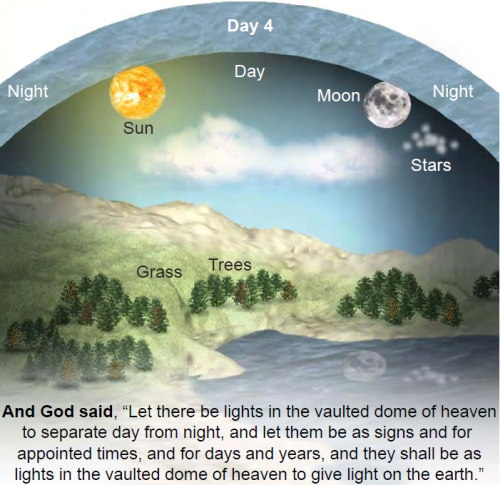

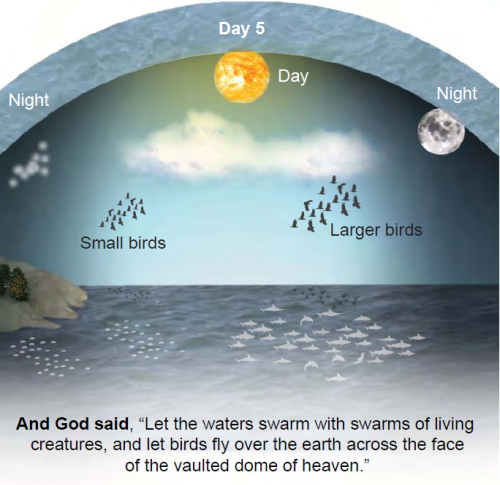

In the “FaithLife Study Bible Infographics” we also find this representation of “The Days of Creation” (fig. 3). Let’s look more closely at Days 2, 4, and 5. First I will show the picture, and then I will comment about it.

Fig. 3. Supposed ancient Hebrew view of the Creation Week, taken from Logos Bible Software 8:14, under “Media Resources” for Genesis 1:6, called “The Days of Creation” in Faithlife Study Bible Infographics.

Fig. 4. Supposed ancient Hebrew view of Day 2, taken from Logos Bible Software 8:14, under “Media Resources” for Genesis 1:6, called “The Days of Creation” in Faithlife Study Bible Infographics.

Fig. 5. Supposed ancient Hebrew view of Day 4, taken from Logos Bible Software 8:14, under “Media Resources” for Genesis 1:6, called “The Days of Creation” in Faithlife Study Bible Infographics.

Fig. 6. Supposed ancient Hebrew view of Day 5, taken from Logos Bible Software 8:14, under “Media Resources” for Genesis 1:6, called “The Days of Creation” in Faithlife Study Bible Infographics.