The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

In answer to Tweedy’s (2024) critique of the CFAH chronology, several ancient sources confirm the testimony of Genesis 10 and the Book of Jubilees (Charles 1913, 8:8–11) that the patriarchs divided the earth into territories.

Keywords: Biblical chronology, Tower of Babel, Noah, division of the earth, Peleg

Tweedy (2024) has critiqued the “Chronological Framework of Ancient History” (Griffith and White 2022a, 2022b, 2023a, 2023b, 2023c) series of papers. We will answer a few of his objections here.

Errata

Before getting to Mr. Tweedy’s main arguments, some miscitations need correction.

Tweedy (2024) wrote that in the MT chronology, Peleg died 48 years after Abraham was born, citing Smith’s “correction” of this error in 2018. However, Ussher had noted that Abraham left Haran the year his father died (Acts 7:4) and thus was born 60 years after his oldest brother, Haran (Ussher 2003 §58, §63, §70). Therefore, using the MT, Peleg died 340 years after the Flood in 2008, 12 years before Abraham was born in 1996 B.C. Ussher observed this five centuries before Smith, and Jones (2019, xiv) used Ussher’s interpretation as well.

Tweedy (2024) wrote that “Pseudo-Manetho (ca. A.D. 400), as cited by Jones (2003, 42), claimed in the Book of Sothis that the Tower event culminated in the fifth year of Peleg’s life.”

The original source of the cited passage does not say the fifth year of Peleg’s “life.” Rather, it says that the Dispersion occurred in the “34th year of the rule of Arphaxad and the 5th year of Phalec” (Manetho 1964, 237–239). We interpret it to mean the Dispersion occurred in the fifth year of the rule of Peleg as a patriarch of his clan, which probably occurred when he was over 50 years of age. The passage can work with either the MT or the LXX, as we have no other sources for when Arphaxad and Peleg began to rule their respective clans. The original Book of Sothis did not contain the comment, therefore “Pseudo-Manetho” did not place the Dispersion in the fifth year of Peleg’s rule, rather an early Christian LXX chronologist almost certainly added it. Our position on the Book of Sothis is that the original list was probably part of Manetho’s Aegyptiaca, but several of the comments were added later by a Christian chronologist in the Roman or Byzantine Era.

Tweedy (2024) also cites Jones as citing Ussher as saying that the Dispersion occurred the year Peleg was born. That isn’t quite correct. For the year 2247, Ussher describes the Tower of Babel, saying “If this happened at the day of his birth, then it seems that . . .” In the following section, 49, Ussher miscites the Book of Sothis saying “The Tower of Babel happened five years after the birth of Peleg.” Then in sections 50 and 52, Ussher cites the 1,903 duration from Ninus to Alexander found in Simplicius and then cites Constantine Manasses for the 1,663 year duration from Menes to the conquest of Egypt by Cambyses. Thus, Ussher did not actually commit to a date for the Tower of Babel, he merely cited four sources for durations to related events falling between 2247 and 2188 B.C.

Complaint About the CFAH Methods

Tweedy (2024) writes:

While this tool seems to provide a means of building a multi-layered fabric defining the times and places of biblical events, the method is subject to certain limitations. One must be careful not to generalize beyond the actual coincidences of dates and places into speculations regarding details that might be nothing more than artifacts of the method. Griffith and White seem to take liberties of assigning significance to near misses to make conclusions such as two divisions of the earth and two dispersions of the peoples.

The example that Tweedy gives of the two dates for the division of the earth is not a case of generalization as he claims. The two divisions seven years apart are explicitly stated in the Book of Jubilees (Charles 1913, Jubilees 8:8–11). The durations to the two events seven years apart are found to agree with the Book of Jubilees, despite coming from different sources, different cultures, and in different units: days and years.

Complications Around the Date of the Dispersion

Speaking of our citation of two durations from China and Peru that seem to place the founding of their nations five years earlier than our triangulated Dispersion date of 2192/2191 B.C., Tweedy (2024) writes:

The authors claim that the division plan was activated twice.

The authors do not claim that the division plan was activated twice. We mentioned the possibility that the Chinese may have organized as a tribe prior to the Dispersion, an idea that is consistent with the comment about Arphaxad and Peleg in the Book of Sothis. We noted two aberrant durations that are close but not precise, both pointing to 2197 rather than 2191 B.C. The fact that we reported these data points without correcting them to match our other results shows that we did not cherry-pick the data. The discrepancy could be the result of two or more possible causes.

First, the durations could be inaccurate or rounded to the nearest ten years. Both the Indian and Peruvian durations are 150 years before or after an event, leaving the possibility of ± 5 years for rounding to the nearest decade. Two thousand, one hundred and ninety-seven minus 5 is 2192 B.C., which is our triangulated date for the Dispersion. The five year divergence in the Chinese date could be due to cumulative error in the chronology of Liu Xin, which we used.

However, neither the Peruvian nor the Chinese durations require an earlier dispersion. The Peruvians dated Noah commanding the people in Armenia to disperse 150 years after the Flood. Later in the text it dates the rule of Manco Opiru to 340 years after the Flood. Therefore the Peruvians must have departed after Noah preached to them, and after the Dispersion, arriving in Peru less than two centuries later, while Noah was still alive, as the text explicitly states. The passage from the Book of Sothis implies that Arphaxad and Peleg had both been ruling their tribes for some time when the Dispersion occurred. Therefore it is not unreasonable to conclude that the Chinese may have recognized Yu as their tribal leader while still at Babel five years before the Dispersion.

Two Divisions or One Seven Year Division Process

Tweedy also criticizes our interpretation of the Book of Jubilees that the division process began seven years prior to the final division in the year Peleg was born, 2247 B.C. The scriptural comment on the birth of Peleg does not exclude the possibility that the division was the result of a multi-year process, it merely informs us the process was completed in the year of Peleg’s birth. Joshua’s conquest and division of the land also appear to have been a seven-year process. Comparing Genesis 10:24 to Joshua 14:5 the Hebrew words are nearly identical both for the land, “ha eras,” and the action of dividing it, “nip̄·lə·ḡāh” meaning “was divided” versus “way·yaḥ·lə·qū” meaning “and they divided.”

Ancient Sources on the Division of the Earth

The ancient Jewish tradition known as the Book of Jubilees gives more detail, informing us there were two divisions, about seven years apart. (Charles 1913, 8:8–11):

And in the sixth year thereof, she bore him a son, and he called his name Peleg; for in the days when he was born the children of Noah began to divide the earth amongst themselves: for this reason he called his name Peleg.

And they divided (it) secretly amongst themselves, and told it to Noah. And it came to pass in the beginning of the thirty-third jubilee that they divided the earth into three parts, for Shem and Ham and Japheth, according to the inheritance of each, in the first year in the first week, when one of us who had been sent, was with them.

And he called his sons, and they drew nigh to him, they and their children, and he divided the earth into the lots, which his three sons were to take in possession, and they reached forth their hands, and took the writing out of the bosom of Noah, their father.

Note that Jubilees says Noah divided the world into three portions for his three sons. However, the patriarchal tradition was that the firstborn son would receive a double portion (Deuteronomy 21:15–17). Therefore, the earth would be divided into the number of sons plus one. If he followed that tradition, Noah would have divided the world into four portions or quarters, and his firstborn son would inherit two of them. That could still be viewed as three portions, though one of the three was the double-portion.

A Sumerian tablet with a fragment of the Legend of Etana also tells us that the achievement that the eight “Great Anunnaki” gods were remembered for was the division of the earth into four quarters or “the four regions” prior to the appointment of the first king, which would place it in the century prior to Nimrod’s first kingdom (Pritchard 1969, 115). Some have recognized the Annunaki as deification of the eight passengers of the Ark (Powell 2022, 469).

The Great Anunnaki [who decree the fate],

[Sat] exchanging their counsels [about the land].

They who created the four regions [...],

The command of the Igigi and all the people [neglected].

The [...] had not set up [a king].

In those days, [no tiara had been tied on, nor crown],

And [no] scepter had been [inlaid] with lapis.

The regions had not been created altogether. (Pritchard 1969, 115)

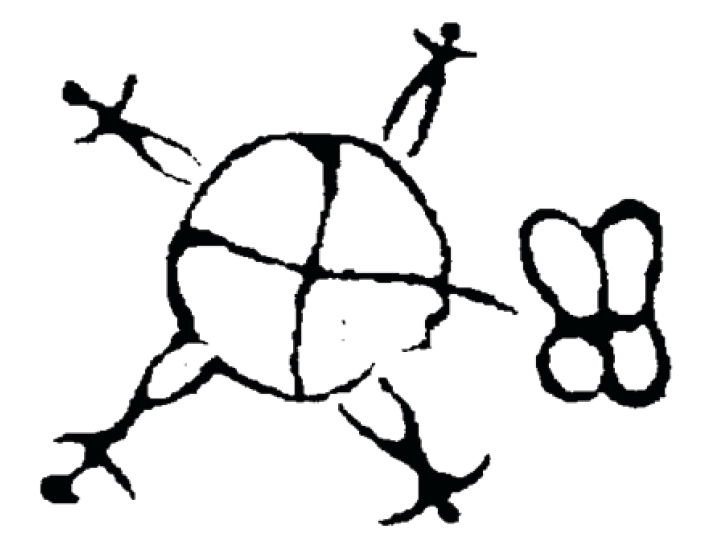

An Armenian petroglyph graphically depicts the four quarters of the earth (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Armenian four quarters petroglyph (Herouni 2004).

Turning now to Plato’s account of Atlantis we find general agreement of the division of the earth by lots, without mentioning Noah by name.

In the days of old the gods had the whole earth distributed among them by allotment. There was no quarreling; for you cannot rightly suppose that the gods did not know what was proper for each of them to have, or, knowing this, that they would seek to procure for themselves by contention that which more properly belonged to others. They all of them by just apportionment obtained what they wanted, and peopled their own districts; . . . Now different gods had their allotments in different places which they set in order. (Plato, 330 B.C.)

Plato goes on to inform us that the lot of the island of Atlantis fell to Poseidon:

I have before remarked in speaking of the allotments of the gods, that they distributed the whole earth into portions differing in extent, and made for themselves temples and instituted sacrifices. And Poseidon, receiving for his lot the island of Atlantis, begat children by a mortal woman, and settled them in a part of the island, which I will describe. (Plato, 330 B.C.)

The Hindus are a fifth witness to the division of the earth among the children of Noah. Hamilton summarizes the Bhagavatamrita, “the Hindus suppose that their ancestors were settling at Mugadha, where they had an undisputed rule for a hundred and fifty years; or from the division of the world, to the usurpation of Pradyato.” (Hamilton 1820, vol. 1, 124)

Did Noah Map the World?

The similarity of the passages raises the legitimate question of how Noah could have divided the earth among his sons without a map.

Charles Hapgood devoted an entire book to showing that the early Portuguese and Chinese maps showed evidence of having been made prior to the Ice Age by a culture that possessed advanced spherical trigonometry (Hapgood 1966).

Given the century between the Flood and the birth of Peleg, there are two distinct possibilities. Noah and his sons may have explored the earth, including the Americas, well enough to make a very rough map. From the time that Columbus discovered the Caribbean in 1492 until the Spanish had roughly mapped the West Coast of South America on the Waldseemüller Map in 1507 was less than 20 years, and their ships were under 18 m in length. The Sumerian King List states that Mes-kia-gasher, whom Rohl identified as Cush (1998), and whom we identify as the first king of Babel, “Mes-kia-gasher went . . . into the [Western] Sea and came forth . . . toward the [Sunrise] Mountains” (Pritchard 1969, 266). Taken at face value, that sounds like Cush circumnavigated the world.

The fact that the Book of Jubilees does not demonstrate knowledge of the Americas does not prove that Noah did not have knowledge of the Americas. Three other ancient sources indicate that the Americas, known to them as the “outer continent” were indeed known to the Egyptians, Babylonians, and even the Greeks, and that the “gods” had divided the world into portions by drawing lots.

The first map is called the T-O map used by the ancient Greeks. This one is turned sideways, as they normally depicted East at the top (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Greek T-O map based on Hecataeus. User: Bibi Saint-Pol, “Hecataeus of Miletus’ Map,” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hecataeus_world_map-en.svg. Public Domain.

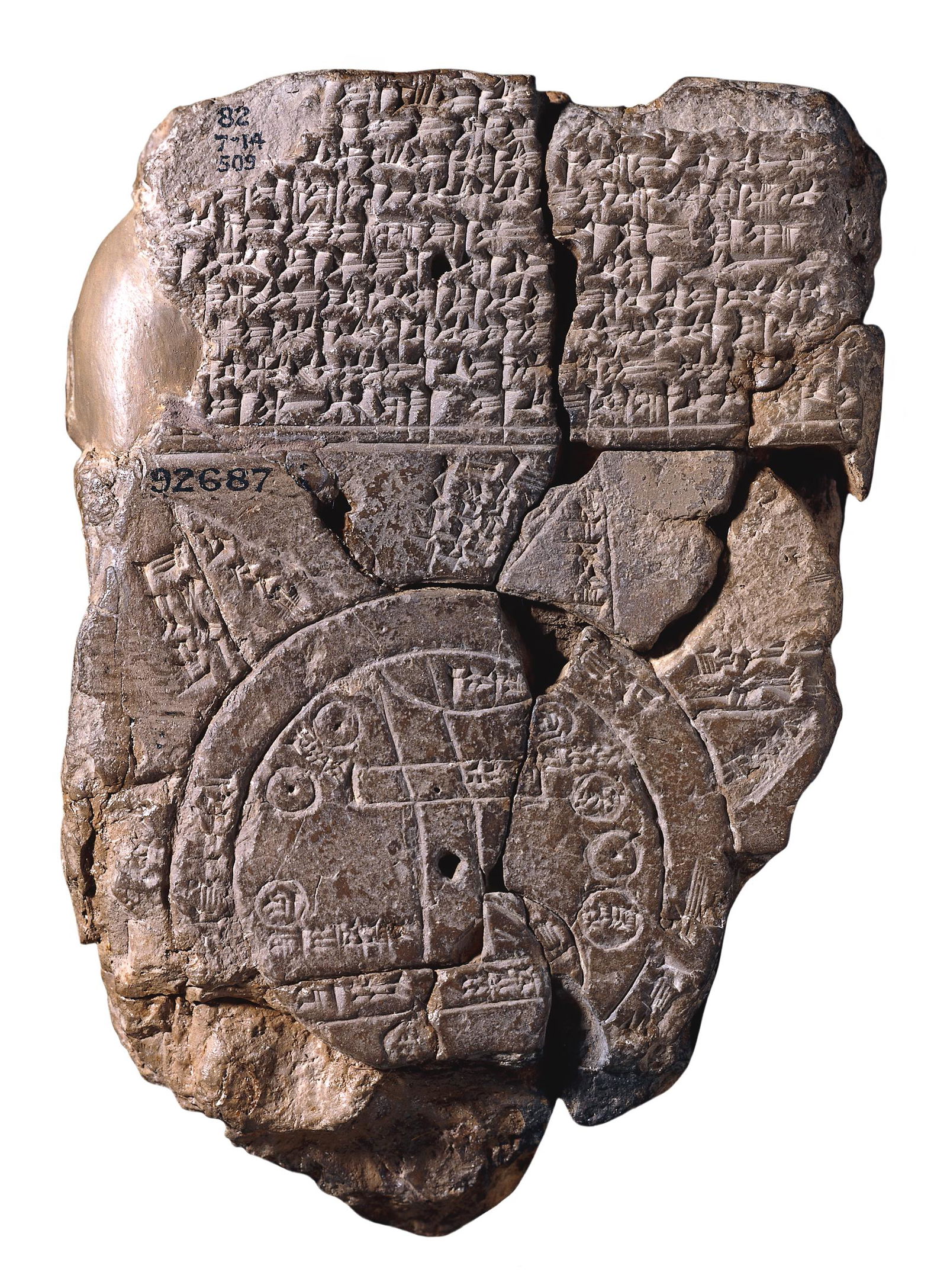

The Babylonian world map shown in fig. 3 is a precursor of the later T-O maps of the Greek Classical Age. It contains more information than the Greek T-O maps. It depicts Asia, Europe, Africa and the Mediterranean in the central disk, with the world ocean around it. It also shows the mountains of the outer continent with labels at the outer edge.

Fig. 3. Babylonian World Map, Sixth Century B.C. “Map showing Assyria, Babylonia and Armenia.” British Museum, Object Number: 92687. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baylonianmaps.JPG. Public Domain.

Proclus was the head of the Platonic school in Athens in the fourth century A.D. He wrote that Marcellus had written about the Atlantic island (Atlantis) before Plato did.

Proclus (1820, 148) quotes Marcellus as follows:

That such and so great an island formerly existed, is recorded by some of the historians who have treated of the concerns of the outward sea. For they say, that in their times there were seven islands situated in that sea, which were sacred to Prosperpine (Persephone), and three others of an immense magnitude, one of which was consecrated to Pluto, another to Ammon, and the one which was situated between them to Poseidon; the size of this last island was no less than a thousand stadia.

The inhabitants of this island preserved a tradition, handed down from their ancestors, concerning the existence of the Atlantic island, of prodigious magnitude, which had really existed in those seas, and which during a long period of time, governed all the islands in the Atlantic Ocean. Such is the statement of Marcellus in his “Ethiopian History.”

This description is remarkable because it indicates that the Greeks at some point had learned from the Phoenicians about the three “outer” continents of Antarctica and the two Americas. These are the “three others of an immense magnitude.” The one consecrated to Amun was probably Antarctica, and the other consecrated to Pluto, or Hades, was probably North America. We can identify the middle island which was dedicated to Poseidon as Atlantis, or South America. It was the inhabitants of the middle island (South America), according to Marcellus, who maintained the tradition of the rule of Atlantis over the other islands. The seven smaller islands probably refer to the isles of the Bahama Bank, Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and Antigua.

Noah and his sons had the experience of building a 157-meter-long vessel, so no one can claim that Noah did not know how to build a ship. If it had been important to the patriarchs to map the world, they had the knowledge, experience, and time to do so.

Tweedy (2024) misses the point that both the Peruvians and the Indians preserved their own traditions that they were either given or taken to their lands less than four centuries after the Flood. The Quito Manuscript says the Peruvians came by boat, not by the Bering Strait. This is their testimony about themselves, and most American Indian tribes, with the exception of the Delaware, say they came to their land by sea on boats or rafts.

Quoting Montesinos using machine translation to English (Hyland 2007, 120):

This is related to the poems and ancient songs of the Indians, and it is in accordance with what many authors say, that at one hundred and fifty years after the flood, there were so many people who grew and multiplied in those lands of Armenia, that Patriarch Noah seeing so much number of people, moved by the urgent need and the divine plan that the men of God had to invade the world, He ordered his children and grandchildren to go with their families to look for lands to settle; and there is no shortage of those who say that the Patriarch himself Noah went to show and distribute the lands, and he gave them away to the whole world. And so this time the first ones left Armenia, settlers and many others on other occasions, some by land along the aforementioned route, and others by sea, as Çedreno and Philon in his Antiquities, according to which it will not be difficult to believe that Noah was in Pirú.

The Peruvian account also confirms quite closely the Masoretic Chronology of the Flood:

After Ophir settled America, he instructed his children and grandchildren in the fear of God and observance of natural law. They lived in it for many years, communicating from parents to children regarding the Creator of all things, for the benefits reziuidos, especially by that of the flood, of which he delivered from the proxinitors of him. They lasted in this property for many years; and according to the count from the cited manuscript, there would be five hundred, counting those of the flood, although according to the opinion of the aumautas and historians Peruvians, it was the second sun after the Creation of the world; that calculating time by common years, well be two thousand years, given that [f.7v / f.79v] was the last of the second sun. And why would these two suns not have been fulfilled when The flood happened, because three hundred and forty years were missing for its fulfillment, according to our most common story, it comes, in opinion of these amautas, to be this age or time of the said three hundred and forty years. (Hyland 2010, 115–116)

Three hundred and forty years short of two “suns” or two thousand years after Creation, comes to the year A.M. 1660, or 2344 B.C. using Ussher’s date for Creation. This differs from the MT date for the six hundredth year of Noah by only four years, suggesting it was rounded to the nearest ten. Thus the Peruvian origin story agrees with the MT within the rounding error. The LXX places the Flood more than 2,000 years after Creation, thus contradicting the Peruvian account.

Given the apparent rounding of the Flood date to the nearest ten, it is not unreasonable to surmise that the 150 years after the Flood was rounded to either the nearest ten, if not the nearest 50. Thus the Peruvian duration agrees with the 2192/2191 B.C. triangulated date for the Dispersion within its error range.

New Babylon versus Old Babylon

Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon is claimed by archaeologists to have been founded in the Akkadian Era (Beaulieu 2017, 50). All parties to this debate agree that Sargon of Akkad lived at least five centuries after the Dispersion. This creates a problem for biblical interpretation. The archaeological evidence could be wrong or misinterpreted, and perhaps Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon was the original. The question is whether the biblical text requires that interpretation. Two later texts of Scripture appears to refer to Jerusalem as Babylon (1 Peter 5:15; Revelation 14:8), suggesting that Babylon as a symbol of spiritual rebellion against God could be applied to different physical locations by the inspired authors.

Amongst creationists, the site currently in vogue for the original Babel is Eridu, first theorized by Rohl (2002) and now promoted by Associates for Biblical Research (Walton 2008; Petrovich 2024) as well as Osgood (2024). Habermehl promotes Tel Brak (2011). The authors have identified the Tigris River Valley near Diyarbakir as the most likely site based on several lines of evidence (Griffith and White 2021a). All of these positions agree that Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon was not the original Babylon.

Tweedy (2024) raises two good questions. The first is geographical, and the second concerns the chain of transmission of the data from the original Babel to Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon. Whether it moved from the north or from the south to the present location, all of these positions agree that Babylon was moved.

Tweedy (2024) quotes the Weidner Chronicle (ABC 19) as saying that Sargon dug earth from the pit of the Esagilia and built a new Babylon opposite Akkad, and argues that this referred to the traditional site of Babylon whose temple-ziggurat complex was called the Esagila (Tweedy 2024). However, the other text speaking of this event, ABC 20, The Chronicle of Early Kings, specifies that Sargon’s digging of the earth from the pit of Babylon occurred during his campaign to Subartu (Livius n.d.). The location of Subartu is reasonably well known to have been in Upper Mesopotamia, not the region of Sumeria (McMahon 2013, 486–501). Tweedy’s argument that Sargon may have created a copy of Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon fails to reconcile all of the sources.

The question is how the priests of Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon could claim a continuous chain of transmission back to the original Babylon, or if they claimed that at all. The fact that Sargon brought sacred earth from the pit of Babylon to build his new shrine strongly suggests he also brought along the priests of that cult. However, there was a second possible route of transmission when the Amorite Kassites also known as Chaldeans conquered Akkad and renamed it Babylon. Whether the Kassites took their name from Abram’s nephew Chesed, or from Arphaxad himself, either way, their conquest of Akkad probably brought a new priesthood with their own historical traditions. Whether the data of Berossus came from the Kassites or from the original priesthood of Sargon’s Akkad, we don’t have enough information at this point to know. The important point is that their historical tradition counted 720,000 days back to the founding of the Tower of Babel, regardless of its location.

Tweedy’s (2024) observation that the 2233 B.C. date for the founding of Babylon in Berossus is only about two centuries lower than the orthodox chronology’s date for Sargon of Akkad is well taken. However, the preponderance of the evidence that other nations date their founding to shortly after 2191 B.C. or later strongly suggests that the date for the First Dynasty of Berossus was just before the Dispersion, not five centuries later.

Supporting this is a new duration we recently received from Nick Liguori, that the Mongolians date the first Khan of the Mongols to 3,250 years before Genghis Khan, whose reign began in A.D. 1206 (Liguori 2024). That places the founding ancestor of the Mongols circa 2045 B.C., less than 150 years after our triangulated date for the Dispersion.

The Chinese Traditions

Griffith and White explicitly acknowledge this by including not only the Shūjīng in their study but also by accepting many other ancient documents at face value.

We don’t necessarily accept all ancient documents at face value. We subject them to our own narrowly defined form of textual criticism (Griffith and White 2022) and recognize that many factors may add to or corrupt the original information.

The Chinese firmly believe that Yáo, Shun, and Yǔ (if they existed) ruled in China, not Mesopotamia. The discussion above regarding succession places all three rulers in China, not Mesopotamia.

Many aboriginal flood legends transfer the location of the Ark landing site to the nearest and highest mountain of the region in which they lived. This phenomenon is found from ancient Assyria to the Americas. The later Chinese might naturally assume that Emperor Yáo fought the flood in China because they experienced the floods of the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers.

Another bit of evidence is that Wu (1982, 66–67, 467) claims that the astronomical data given in the Shūjīng are accurate enough to document c. 2200 B.C. as when the observations were made, which means they could have been made when Shun or Yǔ was emperor.

Having tested the data ourselves (Griffith and White 2023b), we beg to differ with Wu (table 1). The four constellations do not point to a specific year, because they differ by several centuries. Averaging the years they were in those positions gives the 2357 B.C. date claimed by Legge. However, half of them point to an older date, not a more recent one. This could be an artifact of Yao being familiar with the equinoctal positions of the constellations from an earlier period.

Table 1. Yâo’s culminating stars.

| Point | Chinese Star Name | Modern Star Name | Range (B.C.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vernal Equinox | Hsing in Niâo | α Hydrae | 2275–2203 |

| Summer Solstice | Hwo | β and δ Scorpio | 2635–2491 |

| Autumn Equinox | Hsü | β Aquarii | 1987–177 |

| Winter Solstice | Mâo | Pleiades | 2419–2275 |

| Average Year | 2257 |

Tweedy (2024) brings up some good points showing that the Chinese have muddled together traditions about Adam and Noah. A similar problem is seen with the ancient Greeks who could date four floods:

The Flood of Deucalion I—2386–2316 B.C.

The Flood of Ogyges circa—1706 B.C.

The Flood of Deucalion II—circa 1526 B.C.

The Flood of Dardanus—circa 1451 B.C.

The Greek legends attribute elements of Noah’s Flood narrative to all four of their ancient floods. However, the dates distinguish them as different events, three of which were post-flood. It is unsurprising to see the same kind of muddling of Flood narratives with the Adam and Eve narrative in Chinese history.

The Miao Date for Meeting the Chinese

Tweedy (2024, 661) writes: “The tradition states that the Miao first had contact with the Chinese eight generations after Noah and the Flood.”

Genesis 10, which is generally believed to list the tribes just before or after the Dispersion, counts down to sons of Joktan in the sixth generation, not counting Noah. Given the 36-year average for firstborn generations found in the MT for Genesis 11, the eighth generation could have been expected to have been born about 70 years after the Dispersion.

China and the countries of Southeast Asia cover an enormous territory, 50% larger than the continental United States. When it was first settled, two tribes could have wandered in that region for many generations before encountering each other. The Miao story of encountering a hostile Chinese tribe eight generations after the Flood is consistent with the Masoretic Text and the CFAH chronology, which places the Dispersion in the sixth generation after the Flood.

Conclusions

While Tweedy (2024) has pointed out some valid weaknesses with the identification of the Chinese Yáo flood narrative as Noah’s Flood, as well as a five-year discrepancy in the Chinese and Peruvian dates for their migrations, the beauty of the triangulation method is that merely disqualifying one of the source durations is insufficient to disprove the date. To do that one must eliminate all but one of the source durations pointing to that date. Our triangulations to 2233 B.C. for the founding of Babel, and 2192/2191 B.C. for the Dispersion are both supported by multiple durations from different sources in different cultures. Merely plucking out one of them does not collapse our Jenga tower.

We are grateful that Mr. Tweedy was interested enough to study our position and submit his critique. He raised good points and asked excellent questions, and his tone is a great example of how this kind of debate should be done. We look forward to his participation in future discussions.

References

Beaulieu, Paul-Alain. 2017. A History of Babylon, 2200 BC–AD 75. New York, New York: Wiley Press.

Charles, R. H.. 1913. “The Book of Jubilees.” In The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press.

Griffith, Ken, and Darrell K. White. 2021. “An Upper Mesopotamian Location for Babel.” Journal of Creation 35, no. 2 (August): 69–79.

Griffith, Kenneth C., and Darrell K. White. 2022a. “Chronological Framework of Ancient History. 1: Problem, Data, and Methodology.” Answers Research Journal 15 (November 16): 377–390. https://answersresearchjournal.org/ancient-egypt/chronological-framework-ancient-history-1/.

Griffith, Kenneth C., and Darrell K. White. 2022b. “Chronological Framework of Ancient History. 2: Founding of the Nations.” Answers Research Journal 15 (December 14): 405–426. https://answersresearchjournal.org/tower-of-babel/chronological-framework-ancient-history-2/.

Griffith, Kenneth C., and Darrell K. White. 2023a. “Chronological Framework of Ancient History. 3: Anchor Points of Ancient History.” Answers Research Journal 16 (March 22): 131–154. https://answersresearchjournal.org/ancient-egypt/chronological-framework-ancient-history-3/.

Griffith, Kenneth C., and Darrell K. White. 2023b. “Chronological Framework of Ancient History. 4: Dating Creation and the Deluge.” Answers Research Journal 16 (September 20): 475–489. https://answersresearchjournal.org/noahs-flood/chronological-framework-ancient-history-4/.

Griffith, Kenneth C., and Darrell K. White. 2023c. “Chronological Framework of Ancient History. 5: The Babylonian Dynasties of Berossus.” Answers Research Journal 16 (December 20): 635–670. https://answersresearchjournal.org/archaeology/chronological-framework-ancient-history-5/.

Habermehl, Anne. 2011. “Where in the World Is the Tower of Babel?” Answers Research Journal 4 (March 23): 25–53. https://answersresearchjournal.org/where-is-the-tower-of-babel/.

Hamilton, Alexander. 1820. A Key to the Chronology of the Hindus: A Series of Letters in Which an Attempt is Made to Understand the Progress of Christianity in Hindostand by Proving that the Protracted Numbers of All Oriental Nations Agree with the Hebrew Text of the Bible. Vol. 1. Cambridge, United Kingdom: J. Smith, Printer to the University.

Hapgood, Charles H. 1966. Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings: Evidence of Advanced Civilization in the Ice Age. Kempton, Illinois: Adventures Unlimited Press.

Herouni, Paris M. 2004. Armenians and Old Armenia. Yerevan, Armenia: Tigran Metz.

Hyland, Sabine. 2007. The Quito Manuscript: An Inca History Preserved by Fernando de Montesinos. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

Hyland, Sabine. 2010. The Quito Manuscript: An Inca History Preserved by Fernando de Montesinos. Vol. 88. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

Jones, Floyd Nolen. 2019 (1993). Chronology of the Old Testament: A Return to Basics. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Liguori, Nick. 2024. Echoes of Ararat. Vol. 2. Green Forest, Arkansas: New Leaf Publishing.

Livius. n.d. “Chronicle of Early Kings.” https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/abc-20-chronicle-of-early-kings/.

Manetho of Sennebytus. 1964. Manetho. Translated by W. G. Waddell. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

McMahon, Augusta. 2013. “North Mesopotamia in the Third Millennium BC”. In The Sumerian World. Edited by Harriet Crawford, 461. New York, New York: Routledge.

Osgood, A. John M. 2024. “Where in the World is the Tower of Babel—Comments” Answers Research Journal 17 (March 13): 215–216. https://answersresearchjournal.org/tower-of-babel/where-is-the-tower-of-babel-comments/.

Petrovich, Douglas N. 2024. Identifying the Tower of Babel. Nashville, Tennessee: Compass Films. https://www.academia.edu/video/1MaxQ1.

Plato. 360 B.C. Critias. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. https://classics.mit.edu/Plato/critias.html

Powell, James. 2022. “Decoding a World Navel “Visual Language” Through Ideational Cognitive Archaeology.” Answers Research Journal 15 (October 12): 301–337. https://answersresearchjournal.org/noahs-flood/solar-koine/.

Pritchard, James B., ed. 1969. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Proclus. 1820. The Commentaries of Proclus on the Timaeus of Plato in Five Books. Translated by Thomas Taylor. London, United Kingdom: Thomas Taylor.

Rohl, David. 1998. Legend: The Genesis of Civilisation. London, United Kingdom: Butler and Tanner.

Rohl, David. 2002. The Lost Testament: From Eden to Exile The Five-Thousand-Year History Of The People Of The Bible. London, United Kingdom: Greenleaf Press.

Tweedy, Eric. 2024. “Chronological Framework of Ancient History: Parts 1–5. Comments” Answers Research Journal 17: 647–667. https://answersresearchjournal.org/chronology/cfah-1-5-comments-tweedy/

Ussher, James. 2003. Annals of the World. Translated by Larry Pierce. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Walton, John H. 2008. “Is There Archaeological Evidence for the Tower of Babel?” Associates for Biblical Research, 10 May. https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/patriarchal-era/2695-is-there-archaeological-evidence-for-the-tower-of-babel