The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

This is a critique of the application of ideational cognitive archaeology to determining the location of Noah’s Ark. The weakness of the argument is that the author posits, without proof, that the round circle in the Egyptian akhet is Noah’s Ark, and the two peaks on each side are the mountains where Noah’s Ark landed. He then looks at what he claims is this akhet motif in various pagan cultures in the Near East to show that Noah’s Ark most likely landed at Tendurek (site of the Durupinar formation), Turkey. This line of reasoning has led to a flawed conclusion, as Noah’s Ark cannot have landed on a volcano.

Keywords: ideational cognitive archaeology, akhet, Cosmic Mountain, Earth’s Navel, Noah’s Ark, Mount Ararat, Tendurek Mountains, Mount Cudi, Sahand, Sabalan

This paper (Powell 2022) on locating Noah’s Ark using the novel concept of “ideational cognitive archaeology” (I had to look that up) is based on the author’s initial stated assumption that the landing place of Noah’s Ark = Cosmic Mountain = Earth’s Navel (I had to look up those latter two as well; obviously my scientific training did not include a wide enough range of vocabulary). A second assumption he makes is that the solar disk, shown as a round circle in the Egyptian akhet (or ajet), represents Noah’s Ark in this symbol (see fig. 1). Using these assumptions, the author takes a lengthy tour through various ancient pagan cultures, solving what he calls their visual riddles, to determine that they all support Noah’s Ark landing on a twin-peaked mountain. He then says, “The footprint of the historic Genesis Flood is therefore ubiquitous in ancient religious systems.”

Fig 1. The Egyptian akhet, the solar disk resting on the twin-peaked mountain. Luna92. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Akhet.jpg. CC BY-SA 3.0. Abstract

We might wonder on what basis the author makes his assumptions about the Ark. In Egypt, where the twin-peaked icon with the solar disk riding on it is well known, this symbol represents the horizon where the sun rises and sets. An internet search on “akhet” will provide any number of repetitions of this definition.1 The author then looks through the iconography of other ancient cultures to see versions of this symbol. Who are we to go to these ancient peoples and tell them that their symbol does not mean what they say it means? That we know better than they do? While it is true that Noah’s Ark did land in an area of mountains (the Bible says so), why should this pagan icon showing two mountain peaks represent the Ark’s landing place? Why should the solar disk represent the Ark, and not the sun? We may also wonder why the Egyptians used two of this akhet as amulets wrapped in a mummy (see Saleem et al. 2023).

There is, moreover, a risk to hanging a conclusion on unproven assumptions like this. Those assumptions may or may not be valid; and if not, the conclusion can be invalid as well. We need to test Powell’s assumptions by going right to his conclusion at the end of the paper, where he starts to write in clear language, and see where exactly he believes Noah’s Ark settled. Although he offers five possible locations for the Ark, he is certain that the one that meets his specifications best is the Durupinar boat-shaped geological formation at the twin-peaked Mount Tendurek near Mount Ararat in Turkey. . (For information on these sites, see Habermehl 2008; Karaca Dag 2022; Sahand 2022; Sabalan 2022.)

The subject of looking for Noah’s Ark is one that has been on my plate for a long time, starting back in the 1970s. From many years of reading and research, I have reached some conclusions of my own, but they are based on scientific facts, not assumptions. For instance, I am certain that the Durupinar object is not Noah’s Ark. For one thing, Mount Tendurek is a shield volcano that rose after the Flood during the Ice Age, far too late to have been there for the Ark to land on (Habermehl 2008; Mount Tendurek 2022). Creationists have written some good scientific material refuting this location, notably Snelling (1992). Powell says that he knows about the Snelling article, but he is not deterred. His ideational cognitive archaeology arguments override science, we are required to believe. And if we would just do more archaeological research on this site, we would find that the Ark really is there. And if by chance the Durupinar formation itself is not the Ark, there is another possibility nearby. We must admire his unshakable belief, even as we conclude that his arguments are fatally flawed.

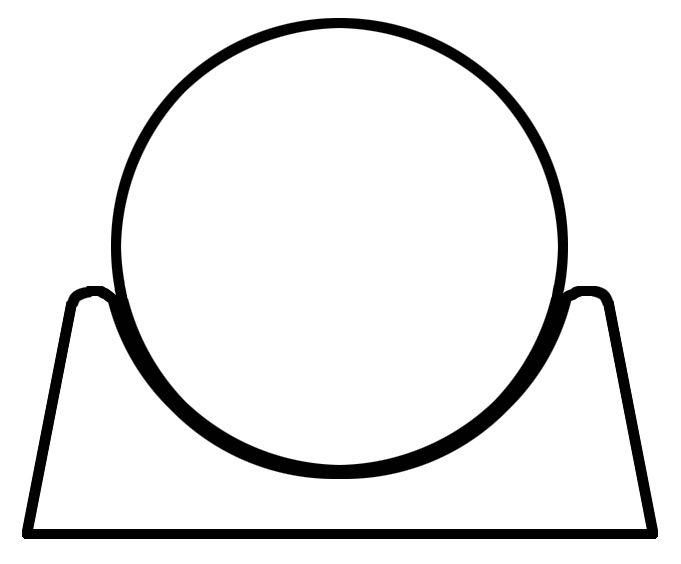

Of the other sites that he lists, but rejects, all are also volcanoes except one. As creationist geologists know, all volcanoes on land rose after the global Flood, and sit on top of Flood deposits. A great deal of effort could be saved if this were understood by the Ark hunters of this world [for example, see Habermehl (2014) re Mount Ararat]. This leaves Cudi Dagh (Mount Judi) as the only possibility out of his list, as it is not a volcano, but instead rose from buckling of the earth’s crust (Ziegler 2001, 457). It is not actually a two-peaked mountain, but is a fairly long mountain ridge that stretches northeast from north of Cizre all the way to the city of Sirnak (see fig. 2). As such, I question whether Mount Cudi should be on Powell’s list at all.2, 3 Also I would comment that Powell does not offer his reasons for choosing his possible Ark locations, as there are many mountains in that part of the world, and using his criteria, the number of possible places for the Ark is large.4 In any case, the Ark cannot be found by simply claiming that a certain location appears to fit his postulated non-scientific criteria.

Fig 2. The Mount Cudi range viewed from Sirnak, Turkey, at the northeast end looking southwest. It is not known where Noah’s Ark landed along this range, but historical indications are that its remains were seen closer to Cizre, at the other end of the range. (Photo: Timo Roller 2013.)

Powell casts his net too wide in looking for icons to back up his theory. For instance, he points to the two pillars, named Jachan and Boaz, that were set on each side of the entrance to Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 7:21); his theory holds that these pillars supposedly represent the two-horned mountain of the Ark’s landing as well. This seems very unlikely because when God gave instructions for building the temple (1 Chronicles 28:19), there would be no reason to include any symbolism with respect to the Ark. Also, the two central pillars in the circles of Gobekli Tepe are claimed by Powell to represent the two-horned mountain. These pillars are not side by side, but face each other, and are oriented so that the sun would not rise and set between them (see The Tepe Telegrams).5 By including the two pillars of Solomon’s temple and the central pillars of the Gobekli Tepe circles in the arguments of his paper, Powell stretches his concept beyond believability.

There are some other questions. Some of the figures in Powell’s paper (figs. 5, 6, 11) contain multiple symbols of a horned mountain. This seems odd because there was only one Ark and it landed in only one place. Also, the Babylonian Map of the World, a sixth-century BC tablet, is claimed by Powell, via various extended assumptions, to show where the Ark landed. Admittedly, I find this difficult to see.

The only mention of an ark anywhere in the pagan literature cited by Powell is in the Sumerian flood account. But this ark lands on “Mount Nimush,” and there is no mention of a two-horned mountain.

Because of my own work on chronology, I mention that the author seems a bit shaky on the connections between secular and biblical dates. He says that a Petrie date of 3500 BC for the pottery of fig. 3 in his paper is shortly after the Flood (if we bring that date forward a bit). That date is a secular archaeological date, and is about 400 years after the Flood based on the MT timeline. Also, he says that the secular date of about 10,000 BC for Gobekli Tepe is “unreliable,” but what does that mean? It is true that GT is a post-Flood settlement, as he says, because that secular date puts it at the end of the Ice Age, well before Abraham. For a comparison of the biblical versus secular timelines see Habermehl (2018), where the secular timeline versus the biblical timeline is shown for both the MT (Masoretic) and LXX (Septuagint).

There are quite a few assumptions made throughout this paper (in addition to the ones that I initially pointed out) in order to make his arguments appear to hang together. Also, words like “probably” and “perhaps” and “may be” and other expressions of uncertainty are sprinkled throughout. I quickly scanned the paper and came up with at least 40 occurrences of these in the main paper, and another 40 in the appendices. This is a lot of uncertainty.

One other thing: Satan must surely have a vested interest in preventing the Ark from being found, because provably finding the Ark would be a huge biblical apologetic. How better to achieve Satan’s ends than by having people look for the Ark everywhere except where it really is? This is especially apparent in how the Ark “moved” from Mount Cudi to Mount Ararat about 700 years ago in popular belief, and how the Durupinar site has picked up its fans, notably followers of the late Ron Wyatt.

Final Comments

It is not for me to say whether the overall concept of ideational cognitive archaeology has validity in the general area of archaeology. But I do not see that this new idea has any usefulness in searching for the Ark. Indeed, what it has really added here is fog. As Powell applies it, requiring acceptance of his initial assumptions (without proof) that the Cosmic Mountain and Navel of the Earth are to be equated with the landing place of the Ark, and that the sun represents the Ark, it is not valid. We already know that the Ark landed somewhere in the mountains of Ararat (Urartu) (Genesis 8:4), and we know that those mountains were formed by land buckling from colliding plates (Ziegler 2001). Powell adds nothing to that.

On paper, theories like this may look good. On paper, we may think that we have found a solution to a problem. But in reality, it is like the square root of minus one, which doesn’t really exist except on paper. Claiming that the Ark must be at Durupinar, based on assumptions, and ignoring science, will find a theoretical Ark location on paper, but will not produce a real Ark.

References

Habermehl, Anne. 2008. “A Review of the Search for Noah’s Ark.” In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Creationism. Edited by Andrew A. Snelling, 485–501. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship.

Habermehl, Anne. 2014. “The Role of Science in Determining the Resting Place of the Ark.” In The Proceedings of the International Noah and Judi Mountain Symposium. Edited by H. Gundogar, O. A. Yildirim, and M. A. Az, 443–460. Sirnak, Turkey: University of Sirnak.

Habermehl, Anne. 2018. “A Creationist View of Göbekli Tepe: Timeline and Other Considerations.” In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism. Edited by John H. Whitmore, 7–13. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship.

Karaca Dağ. 2022. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karaca_Da%C4%9F.

Mount Tendurek. 2022. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Tend%C3%BCrek.

Powell, James. 2022. “Decoding a World Navel ‘Visual Language’ Through Ideational Cognitive Archaeology.” Answers Research Journal 15 (October 12): 301–337. https://answersresearchjournal.org/noahs-flood/solar-koine/.

Sahand. 2022. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sahand.

Sabalan. 2022. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sabalan.

Saleem, Sahar N., Sabdah Abd el-Razek Seddik, and Mahmoud el-Halwagy. 2023. “Scanning and Three-Dimensional Printing Using Computed Tomography of the ‘Golden Boy’ Mummy.” Frontiers in Medicine 9 (January 24). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.1028377/full.

Snelling, Andrew. 1992. “Special Report: Amazing ‘Ark’ Exposé.” Creation Ex Nihilo 14, no. 4 (September): 26–38.

Snelling, Andrew A. 2017. “Is Noah’s Ark on Mount Ararat?” Answers 17, no. 3 (May 1): 54–62. https://answersingenesis.org/noahs-ark/noahs-ark-found/noahs-ark-mount-ararat/.

The Tepe Telegrams. n.d. “News and Notes from the Gobekli Tepe Research Staff.” https://tepetelegrams.wordpress.com/the-research-project/.

Ziegler, Martin A. 200l. “Late Permian to Holocene Paleofacies Evolution of the Arabian Plate and its Hydrocarbon Occurrences.” GeoArabia 6, no. 3 (July 1): 445–504.