The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

For a hundred years, the conventionally accepted Egyptian chronology, which is without certainty beyond 690 B.C., has been used as the ‘gold standard’ for the chronology of the ancient world and has been the instrument for severe skepticism of the biblical history. Biblical archaeologists nonetheless have attempted in vain to use assumed correlations with it to ‘prove or correlate the Bible.’ The result has been vague and unconvincing, yet it holds these people in its grip like a magnet. The only period of Egyptian history that fits the account of Israel’s sojourn is the Middle Kingdom, and the only collapse of Egypt that fits the collapse during the Exodus—as portrayed in the Bible—is the Second Intermediate Period, which began in the early XIIIth Dynasty. However, the details of the XIIIth Dynasty have eluded authors without any certain consensus. This discussion presents a new arrangement, a different model of the XIIIth Dynasty for discussion. This model brings a new order into that early period prior to Egypt’s collapse and also suggests possible candidates for Pharaoh at the time of the Exodus.

Keywords: Byblos kings, contemporary reigns, dominant kings, subsidiary kings, Turin Canon

Introduction

The abstract will undoubtedly upset some conventionalist chronologers, and, before I address the subject of the XIIIth Dynasty, which I will argue is relevant to the Exodus, I will address those sentiments. The reader, however, needs to understand that the purpose of this article is not for academic niceties but to affirm that the Bible’s record is accurate and that its message is the only message that can bring hope to the world. This is its sole purpose.

If the Bible’s history is not true and accurate, then neither is its message which is based on promises and covenants given at particular points in history. In any legality—and promises and covenants are legal entities—several things are absolutely required: a date (that is, a point verifiable in history), witnesses, and statements to whom the parties in those legalities pertain. This is the reason the Bible alone among the great religious books demands chronological statements and genealogies, often emphasizing them.

However, over the last century, great confusion has attended the attempt to correlate the Bible’s record against archaeological findings dated to the conventional Egyptian chronology. As a result, some very prominent “biblical archaeologists” (I will not, for their sake, name them), even some who have come from Christian families, have turned from their faith. They do so because their assumed secular chronology, the history which they have come to believe, does not correlate with the claims of the Bible. Others have taken the course of minimizing the biblical record to fit with their theories or have turned to other genealogies, such as those of the Septuagint (of which there are at least three versions) or the Samaritan text. Others have turned to outright hostility against the claims of the Bible and insisted that it is based on myth. Still, others have desperately clung to vague correlations in order to hold to their faith.

Similarly, several Jewish archaeologists have accepted this elongated secular chronology and the claims of a later composition of the Torah documents. They have disregarded or minimized the historical realities and the Exodus claims that underly their own relationship with their God who made His covenants with them. An example of such a minimization was published in an earlier edition of Answers magazine by a biblical archaeologist who claimed that Israel’s invasion of the Holy Land left no footprint (Smith 2014, 80–84). Why? Because he is influenced heavily by much of the accepted secular chronology which simply does not match. So, apparently, a new civilization that almost completely wiped out a former civilization left no trace! Finding archaeological and historical evidence of such a civilizational overthrow anywhere else in the world would not be a problem; but, when it comes to Israel and the Bible, apparently no such evidence exists. Really?

Let me be very clear—The major reason for these reactions is the sequentially-interpreted Egyptian chronology with its assumed older B.C. dates which has become the dominant chronology of the ancient world by consensus and the enforced gold standard by which all others must therefore give way. I will maintain that unless one begins with the claimed absolutes of the Bible’s chronology as the starting point, an adequate correlation is doomed to failure.

Is this accepted Egyptian chronology a satisfactory yardstick? Consider a quote by Leo Depuydt (1993, 269):

With 690 BC, the explorers of Egyptian chronology have reached the edge of familiar territory on their journey into the past and are overlooking a vast unmapped area into which it is possible to make expeditions, but of which no precise measurements can be obtained.

690 B.C. is the date of the accession of Kushite Taharqa of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. This event is verifiable because Taharqa finds mention in the Bible (2 Kings 19:9) within the account of Sennacherib’s aborted second attack on Judah in 689 B.C. (Shea 1985, 401–418). This is the last verified date into the past between the biblical chronology and the currently held Egyptian record. Beyond this, significant doubts and debates exist. So much for “proven” Egyptian history. As a result, the present author does not accept any date attributed by the presently accepted chronology before 690 B.C.; I consider that they must all be taken as suspect.

But some will claim that their dates can be guaranteed astronomically. However, in 701 B.C., Hezekiah witnessed a 10° backshift of the sundial’s shadow. Such a phenomenon demands a slight shift in the earth’s axis. This would invalidate all B.C. astronomically determined dates before 701 B.C. which are calculated without this factor being taken into account. I therefore do not accept dates calculated without this factor, and I am unaware of any that have taken that into account.

Why Is the XIIIth Dynasty Important?

To be clear, the Biblical record of the collapse of Egypt and the Exodus is profound: It was not a sideshow. God said of the judgment on Pharaoh, “For this cause have I raised you up, for to show in you my power, and that my name may be declared throughout all the earth” (Exodus 9:16; emphasis added). So why are the Biblical archaeologists having so much problem finding the Exodus? The reason is that they are looking in the wrong place as a result of adherence to a false timeline.

So where should one look? A good start may be made by drawing a line of the biblical chronology (absolute exactness is not necessary) from the Flood to the established Hellenistic period. And then, against it and at the same length, draw a linear arrangement of the total archaeological horizons from the Holy Land. A combination of Jericho and Hazor gives most of the spread needed. This simple exercise then places the Exodus close to the beginning of the Middle Bronze of Palestine (end of Early Bronze III of Palestine). Why do we not see this simple exercise in publications by “biblical archaeologists”?

The reader may notice that I do not mention the B.C. dates which are often used, and this is because primarily using these blurs the discussion by bringing into it the presenters’ own B.C. date bias. Most of these dates have not been established except in the assumed sequential interpretation, which is the inherent problem. The presentation should first be in date-neutral archaeological horizons with archaeological synchronisms. Let us then look at the Egyptian Dynastic arrangement (even with its problems) and why I equate this identification to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty and early Thirteenth Dynasty, which belong to the Early Middle Bronze of Egypt.

Now the Bible’s record demands that at the Exodus Egypt had been substantially destroyed—socially, economically, and militarily! Therefore, only a period that fits that description can qualify if one is to be faithful to the record.

Five Suggested Periods for the Exodus

Scholars suggest five different periods for the Exodus. The periods that have been considered most are the following:

- The “First Intermediate Period”

- The beginning of the Second Intermediate Period

- Sometime during the Second Intermediate Period

- The Eighteenth Dynasty, most particularly Amenhotep II

- During the Nineteenth Dynasty: the Ramesside Period

Let us examine these.

-

The First Intermediate Period is entirely based on the interpretation of the sequential chronology. I have never seen any concrete evidence that gives credence to a 200-year gap between the Old Kingdom and the beginning of the Middle Kingdom. Rather, this period can adequately be explained by separate and parallel rules in the various cities of Thinis, Heracleopolis, Thebes, and Memphis. In other words, a fragmented but still intact series of administrations exists. There is no convincing positive evidence of the Exodus conditions during this period.

-

The Second Intermediate Period is better known to us and does witness a collapse or fragmentation of administrations. It also witnesses an invasion. Although modern scholars are doing their best to soften such a conclusion, on the testimony of both Manetho and Eighteenth-Dynasty Hatshepsut, there was an invasion of ‘Asiatics’ into Egypt. As Manetho (as quoted by Josephus 1974, 162–63,1 C. Ap. 1.14; cf. Rohl 1995, 280–281) says: “And unexpectedly, from the regions of the East, invaders of obscure race marched in confidence of victory against our land. By main force they easily seized it without striking a blow; and having overpowered the rulers of the land, they then burned our cities ruthlessly.” Manetho continues the description, but modern scholarship has more recently downgraded his claims; but even if exaggeration is present, something of drastic nature remained in the consciousness of the native Egyptians, and such was again emphasized later by Eighteenth-Dynasty Hatshepsut. She claimed ‘Aamu’ were in the land (Rohl 2007, 94). The term has been usually translated as ‘Asiatic;’ but there is reason to believe that it is an Egyptian derivative for Amalek, Egypt’s nearest eastern desert neighbor and the significant enemy of Israel during the time of the Judges (here held to be Middle Bronze of Palestine). Furthermore, there is no mention in the Bible of native Egyptian armies affecting the land of Israel during the times of the judges.

There is also a testimony (much argued over) to the breakdown of social conditions throughout the land during this period—The Ipuwer Papyrus. Additionally, recent excavations at Tell el-Dabʽa, ancient Avaris and Pi-Rameses, have shown the following progression: An initial early group of resident ‘Asiatics,’ then a gap at the appropriate period, followed by a second group of ‘Asiatics.’ This period witnesses all the necessary conditions.

-

Some would place the Hyksos Period of the Second Intermediate Period as the time of the sojourn (this equates to the second group of Asiatics at Tell el-Dabʽa). This was the position of the Jewish historian Josephus (1974, 162–164, C. Ap. 1.14). The major problem with this identification is that those ‘Asiatics’ were more often than not in control of a large portion of the land, and that does not match the biblical testimony.

-

The Eighteenth Dynasty—most particularly Amenhotep II (A II). This identification surprises me and is wholly based on acceptance of the secular chronology. There is no evidence of the type of collapse mentioned in the Bible, nor of military collapse, and A II is followed by a series of powerful and dominant kings of the same dynasty. To accept this identification, one has to diminish the Bible record.

-

The Nineteenth Dynasty—most particularly the Ramses II time period.

Again, this is heavily based on the association of the name Rameses, and most who hold this position seem to either not know or ignore Courville’s identification of Ramesside names during the Twelfth Dynasty, or they claim that these are misplaced Twentieth-Dynasty kings. Moreover, while there was a fragmentation after Ramses II, all the dynasties that ruled had reasonably strong armies, and evidence of significant social breakdown is lacking.

This period also is associated with another mythical period. The so-called collapse of the Bronze Age, which is coordinated with the mythical dark age of Greece, is an entirely modern construct based on a belief in the sequential arrangement of the Egyptian chronology. This has grossly distorted ancient historical records, pushing contemporary kingdoms apart by up to 400 years and bringing total confusion into otherwise contemporary kingdoms. This distortion is most evident with the Hittites and the Kassites, but it has also distorted the Assyrian record without justification.

Of the above, only the beginning of the Second Intermediate Period satisfies the conditions and also fits the archaeological horizon previously identified with our suggested time-line graph. This period began with the end of the Twelfth Dynasty and the rise of the less understood early Thirteenth Dynasty, when a collapse of Egyptian rule becomes evident. Manetho (as quoted by Josephus 1974, 162–163, C. Ap. 1.14; cf. Rohl 1995, 280–281) says of this time that “a blast of God smote us,” which was followed soon after by “invaders of an obscure race” who “overpowered the rulers of the land” (note the plural “rulers”) and caused an oppressive period. The latter has somewhat been watered down by some later authors, but it is of some interest that one of these early rulers had a scarab which Petrie (1917, xxi, plate 15.1) reads as, “Prince of the desert Ontha, the terror.”

For the sake of clarity, let me state that I place the Exodus at this collapse and date it to the biblically derived date of 1,446/7 B.C., derived as a result of the statement in 1 Kings 6:1, which is here placed at 967 B.C. I am not here going into a tedious, prolonged discussion as to why I start with this date, and the majority of variations only add up to a few years’ difference anyway.

I also accept the sojourn of Israel in Egypt as 215 years. I reject the claimed 430-year interpretation, which I believe comes from a misunderstanding or misreading of Paul’s statement in Galatians 3:17.2 The Apostle clearly indicates that the 430 years is from the promise to Abraham (Genesis 12:7) until the giving of the Law at Sinai (the year of the Exodus), the actual sojourn being half of this.

Let me quickly give some of my starting premises. I identify the beginning of the famine in year 25 of Sesostris (Senusret) 1 as the famine of Joseph, witnessed by two officials Mentuhotep and Ameny. Jacob’s entry into Egypt took place in 1662 B.C., in the twenty-sixth year. Sesostris (Senusret) III was the “king that knew not Joseph” (Exodus 1:8). On the termination of the Twelfth Dynasty, with the Thirteenth now in place, the situation was now that “the king of Egypt died” (Exodus 2:23) and a different administration was in place. The threat to Moses was now gone. I also claim that the major connection of the Hyksos is, in fact, the desert tribe of Amalek, which has been cited by several authors previously.

Having stated where I stand, it is not my intention to spend time explaining these dates, which I have elsewhere explained in detail (Osgood 2020).

The Thirteenth (XIIIth) Dynasty

The interpretations of the history of Egypt’s XIIIth Dynasty have been legion, with little final agreement on the overall history despite the excellent recent work by Kim Ryholt (1997, 2004, 135–155). This dynasty is relevant to biblical correlation for the time of the Exodus and certainly presents a challenge to any interpretation, let alone a biblical one.

The details of the XIIIth Dynasty are found in the much-mutilated Turin canon (which will be much mentioned), in the damaged and apparently not very chronological Karnak List, and possibly one of its kings is mentioned in the much-neglected Hellenised Sothis list. Egyptian priest Manetho in his now poorly recorded History of Egypt (Aegyptiaca) gives no detailed information of the kings of this period. The arrangement of the XIIIth Dynasty in the Turin Canon is sequential and has for the most part been interpreted in that sequential order. The Turin Canon has at least 80 kings enumerated. It is because of the sequential interpretation of this papyrus that this reconsideration is being presented.

Elsewhere, I have pointed to the fact that Manetho and possibly all his sources, which would have included the forerunners of the Turin Canon, the Abydos and Sakkara lists, are arranged, as was the fashion of many of the ancient lists, by listing often contemporary dynasties in sequential form (Osgood 2020, 247–250). The lists of kings are also often arranged geographically in the Egyptian lists. Therefore, the linear added time in no way represents the time periods covered. This point is also made by Olga Tufnell (1984, 155):

There is one point about the composition of the Turin Canon—indeed all ancient king-lists—which needs emphasizing since it plays a significant role in the present chapter. Dynasties or other groupings of kings are usually listed as if in a single chronological sequence so that exterior controls are required in order to define contemporary, competing or overlapping dynasties. Precisely this situation is evident in the Turin Canon in both the First and Second Intermediate Periods.

Tufnell (1984, 156) adds concerning the XIIIth-Dynasty Turin kings:

Faced with scores of ephemeral kings about whom little may have been known in Empire times, the compiler of the Turin Canon simply gave their names as tradition had handed them down. If the author himself had any specific sequence in mind, this escapes us completely; it may have been geographical rather than chronological.

With the XIIIth Dynasty, I have pointed out that a case can be made that the early XIIIth Dynasty as presented in the Turin Canon may well represent several contemporary dynasties arranged sequentially (Osgood 2020, 269–271). And, I have suggested at least three contemporary lines of kings, with at times one pharaoh dominant at any moment, usually controlling the town of It-tawy (the major capital of the Twelfth Dynasty). This arrangement is a possible explanation of Egyptian kings’ names, wide apart in the Canon, being found together in contemporary sources.

Contemporary Sources

Following are some contemporary and related sources suggesting contemporaneous Egyptian reigns. After reviewing these, I will put forward the three lists extrapolated from the Turin Canon. Reference to those lists is relevant.

Two significantly strong sources

The first of the contemporary sources comes from the commercially relevant Phoenician city of Byblos, which was over many centuries in communication with Egypt (perhaps as a vassal in some cases). The relevant details concern several generations of Byblos kings who clearly were in communication with Egyptian Pharaohs (see table 1).

Table 1. Byblos kings and the Egyptian rulers they were in communication with by Dynasty.

| Byblos Kings | Egyptian Pharaohs | Dynasty |

|---|---|---|

| Abi-shemu | Amenemhet III | Twelfth |

| Yapi-shemu-api (son of Abi-shemu) | Amenemhet IV (AIV) | Twelfth |

| Yakin-el | Sehetepibre III (T 6:12) | Thirteenth |

| Yantin-ˊammu (son of Yakin-el) | Neferhotep I (T 6:25)3 | Thirteenth |

On the latest revised Turin Canon list, Sehetepibre (Sewesekhtawy) and Khasekhemre Neferhotep I are 15 kings apart on the list but only one generation apart in the Byblos list. And, they appear not very long after the demise of the Twelfth Dynasty, represented by its last male king Amenemhet IV (A IV). In the three lists (see further), these will be seen to be close in suggested time but on two different lists.

The second strong source is that of Vizier Ankhu. Ankhu was vizier under Userkare Khendjer (Turin 6:20) and Sekhemre-Khutowe Amenemhet Sobekhotep I4 (T 6:5), which demands a close relationship in time, even though these two rulers are far-separated in the Turin Canon (see table 2). Ankhu is believed to be the son of a vizier named Zamonth who served under Amenemhet III (T 5:25). Ankhu is also believed to have served under three more kings: (1) Smenkhkare Imyremeshaw (T 6:21), (2) Sehetepkare Intef (T 6:22), and (3) Seth Meribre (T 6:23). He also appears to be associated with the name of Amenemhet III in Papyrus Brooklyn 35. This association of Ankhu demands a very early reign of Userkare Khendjer—very soon after the fall of the recognized Twelfth-Dynasty kings—and suggests that several of the kings before him may well have been before or parallel to the termination of the Twelfth Dynasty (see table 2).

Table 2. Egyptian pharaohs and their viziers. Highlighting emphasizes the gap in the Turin Canon between Sekhemre- Khutowe Sobekhotep I and Khendjer.

| Egyptian Pharaoh | Vizier | Turin List |

|---|---|---|

| Amenemhet III | Zamonth/Ankhu | T 5:25 |

| Sekhemre-Khutowe Sobekhotep I | Ankhu | T 6:5 |

| Khendjer | Ankhu | T 6:20 |

| Imyremeshaw | Ankhu | T 6:21 |

| Sehetepkare | Ankhu | T 6:22 |

| Seth Meribre | Ankhu | T 6:23 |

Note that the literature concerning Ankhu often uses the name ‘Sobekhotep II’ as one of the Pharaohs under whom Ankhu served. However, this king has been identified with two different kings: Sekhemre Khutowe Amenemhet Sobekhotep I5 (T 6:5) and Khaankhre Sobekhotep II6 (T 6:15). Either way, the argument still holds, but it is even stronger with the first, which seems on the whole to be the king indicated. The next earliest king that Ankhu is recorded as serving under is Khendjer (T 6:20).

Two less certain sources

The third source is less certain than the other two. Held at the Louvre (AF8969) is a headless, seated statue of Khaankhre Sobekhotep I7 (T 6:15) (Davies 1981, 22). Its sides are decorated with an effaced prenomen which is either Khaneferre (T 6:27) or Khahotepre (T 7:1); it is most likely the latter for reasons of filiation (there is a degree of ambiguity in Davies’ discussion, however, which could possibly remove this from consideration). These kings in the Turin Canon are at least 11 or 12 names apart; but this statue suggests Khaankhre may also have taken the name Khahotepre (or less likely Khaneferre), making these two kings one and the same.

Moreover, Julien Siesse and Simon Connor (2015, 227–247) have argued on stylistic grounds that Khaankhre reigned after Sobekhotep IV (Khaneferre). This would add to the possibility that Khaankhre (T 6:15) and Khahotepre (T 7:1) were one and the same—the former being a Pharaoh identified by Courville (1971, 122) (from the name in the Sothis List) as the Pharaoh of the Exodus.

There are several other artifactual evidences suggesting such contemporaneity.

A fourth source is the Nile flood levels. At Semna and Kumma, near the second cataract in southern Egypt are several Nile flood levels, almost all related to the Twelfth and early Thirteenth Dynasty. The flood levels are associated with different rulers (Yvanez 2010):

- 16 for Amenemhet III,

- 3 for Amenemhet IV, and

- 1 for Sobekneferu.

Then:

- 3 for Sekhemre Khutowe Amenemhet Sobekhotep 1 (T 6:5) of the Thirteenth Dynasty,

- 1 for Sekhemre Amenemhet Sonbef (T 6:6) of the Thirteenth Dynasty, and

- 1 for Sedjefakare Kay Amenemhet (T 6:18) of the Thirteenth Dynasty.

The fourth and fifth kings in the above list are frequently related by authors, with filiation, to the last kings of the Twelfth Dynasty (though the exact filiation is subject to debate). The sixth king, however, Sedjefakare is 12 kings later on in the Turin Canon, and, as such, a sequential interpretation places him strangely out of place. I would suggest, however, that this king is to be found early on a second, contemporary list and is another king related to the last kings of the Twelfth Dynasty, but one who ruled in a different city. As such, I suggest that the fourth, fifth, and sixth in the above list all have common filiation; and all ruled early, possibly around the time of the end of the Twelfth Dynasty or contemporary with its end. The common name Amenemhet to all three would lend some credibility to this. A close time relationship would also be consistent with the early scarab types as listed by Tufnell (1984, 159).8

Different Authors’ Placement of the “Collapse”

Fifth, another source/evidence that indicates contemporaneous reigns of Egyptian kings within the Turin canon is the collapse of Egypt. The collapse of Egypt at the beginning of the Second Intermediate Period, here related to the moment of the Exodus, is identified in three sites in the Turin Canon by different authors (somewhat in accordance with their interpretation of that event; that is, collapse by some, Exodus to others). Such disagreement would give the idea that they “can’t all be right,” but I am going to suggest here that when an arrangement of three parallel lines is appreciated, “they are, in fact, all correct!”

Let me explain the three views:

- Albright (1945, 15) and Säve-Söderbergh (1951, 53–71) took the view that the collapse occurred after the reign of Sobekhotep III (T 6:24) through to Khaneferre (T 6:27). In my list, I have added Khahotepre Sobekhotep V (sometimes VI), who is next on the Canon (T 7:1), as a result of his scarab found at Jericho.

- Courville (1971, 1:118–129) points out the name ‘Koncharis’ (interpreted as Kha-ankh-re) in the Sothis List, listed between the last Twelfth-Dynasty kings (Ramesside names) and the first Hyksos king, and suggests that this king was the one ruling at that period.

Now the Sothis list, which is a list presented to us in the ninth century A.D. by George Syncellus, has understandably come under severe criticism. It is a Hellenized list of 86 kings of Egypt, some of which are difficult to identify. The Book of Sothis has generally been disregarded by conventionalists. However, the Sothis list clearly has been made from previous sources which come eventually from Egypt. The first 46 kings are in chronological order (but not necessarily historically complete). Now this has been questioned because, as Courville (1971, 118–122) points out, at the place we would expect the Twelfth Dynasty, there is a list of Ramesside names. Conventionalists have assumed that these are a misplaced list of Twentieth-Dynasty Ramessides. The problem, however, is that those simply do not match. Therefore, Courville (1971, 118–122) understandably has insisted that these are alternate names of the Twelfth-Dynasty kings, and such would fit with the placement of these in the list. After all, with Courville’s (1971, chapter 11) claim that Israel’s sojourn occurred during the Twelfth Dynasty, along with the need to build ‘Rameses’ a treasure city for Pharaoh during that sojourn, such would be a perfectly reasonable match. But conventionalists have met the claim generally with silence. This hypothesis also negates the claims by some conventionalists that the name ‘Ramses’ was later retro-placed into the Bible, a claim that is pure supposition.

Following these Ramesside names is a list of known names of Hyksos rulers and sandwiched alone between the two groups is the name ‘Koncharis,’ the only king named between the two lists. The question then is why has this king, who to the conventionalists is obscure, been singled out for the end of the Twelfth Dynasty and before the Hyksos kings? That question has no right to be dismissed out of hand, as has generally been the case. Such a question becomes more pertinent when we discover that Koncharis (“K-oncha-ris” [Hellenized]; “Kha-ankh-re” [Egyptian]) is the first king since the great unifier Mentuhotep II (Eleventh Dynasty) to claim the Horus name Sema Tawy—‘uniter of the two lands.’

- Rohl (1995, 284) has suggested a third placement for Egypt’s collapse under Pharaoh Dudimose (of which there are two—T 7:12 and T 7:13). This suggestion is argued due to the correspondence of Dudimose to the Timaus/Tutimaos mentioned in Manetho as the Pharaoh in whose day “the blast of God” hit the Egyptians (as quoted by Josephus 1974, 162–163, C. Ap. 1.14; see Rohl 1995, 278–284). The Dudimoses are, however, quite late in the list, definitely later than the previous two suggestions.

When the 3 lists are placed side by side (see table 3), the candidates, contemporary on the lists, for the pharaoh of this moment are the following: Khaankhre Sobekhotep II, Khahotepre Sobekhotep V (or VI), and Djedhotepre Dudimose II (all highlighted in table 3). And, we have already pointed out the possibility that Khaankhre and Khahotepre may have been one and the same person ruling in the north (Memphis and It-Towe); while Dudimose can only be relegated to the south (Thebes). Following are the three lists that I have extrapolated from the Turin Canon (see table 3).

Table 3. Proposed contemporary lists 1–3. The numbers under “Turin List” represent column and number, as designated by modern interpreters. Some variation does still exist. Potential candidates for the ruler during Egypt’s collapse at the beginning of the Second Intermediate Period are highlighted. Kings without numbers are rulers judged to be named in the lacunas of the damaged Canon—still under debate. All rulers after Dudimose II are believed to be vassals under the Hyksos.

| Ruler | Length of Reign | Turin List | |

|---|---|---|---|

| List 1 | Sekhemre Khutowe Sobekhotep I | 3 years (?) | T 6:5 |

| Sekhemre Amenemhet Sonbef | 5 years (?) | T 6:6 | |

| Nerikare (?) | 1 year (?) | T 6:7 | |

| Sekhemre Amenemhet V | 3–4 years | ||

| Ameny Qemu | T 6:13 (?) | ||

| Hotepibre Qemu Siharnedjheritef | T 6:8 | ||

| Iufni | T 6:9 | ||

| Seankhibre Ameny-Intef Amenemhet VI | T 6:10 | ||

| Semenkare Nebnuni | 2 years (?) | T 6:11 | |

| Sehetepibre Sewesekhtawy | T 6:12 | ||

| Sewadjkare I | T 6:13 | ||

| Nedjemibre | T 6:14 | ||

| Khaankhre Sobekhotep II | 3 years | T 6:15 | |

| List 2 | Renseneb | 4 months | T 6:16 |

| Awibre Hor | [. . . and] 7 days9 | T 6:17 | |

| Sekhemrekhutawy Khabau | 3 years | ||

| Djedkhepereu | 2 years | ||

| Sedjefakare Kay Amenemhet VII | 6–7 years (?) or 3 years (?) | T 6:18 | |

| Khutawyre Wegaf | T 6:19 | ||

| Userkare Khendjer | 4 years, 3 months | T 6:20 | |

| Smenkhkare Imyremeshaw | 10 years | T 6:21 | |

| Sehetepkare Intef | T 6:22 | ||

| Seth Meribre | T 6:23 | ||

| Sekhemre Sewadjtawy Sobekhotep III | 4 years, 2 months | T 6:24 | |

| Khasekhemre Neferhotep I | 11 years, 1 month | T 6:25 | |

| Menwadjre Sihathor | 3 months | T 6:26 | |

| Khaneferre Sobekhotep IV | 10–11 years | T 6:27 | |

| Merhotepre Sobekhotep V | 3 years (?) | ||

| Khahotepre Sobekhotep VI | 4 years, 8 months, 29 days | T 7:1 | |

| List 3 | Wahibre Ibiau | 10 years, 8 months | T 7:2 |

| Merneferre Ay | 23 years, 8 months, 18 days | T 7:3 | |

| Merhotepre Ini | 2 years, 2 months, 9 days | T 7:4 | |

| Sankhenre Sewadjtu | 3 years, 2 months | T 7:5 | |

| Mersekhemre Ined | 3 years, 1 month | T 7:6 | |

| Swadjkare-Hori | 5 years, 8 months | T 7:7 | |

| Merkawre Sobekhotep VII | 2 years, 6 months | T 7:8 | |

| Merankhre Mentuhotep V | T 7:9 | ||

| Djedankhre Mentuemsaf | T 7:10 | ||

| Seneferibre Senwosret IV | T 7:11 | ||

| Djedneferre Dudimose I | T 7:12 | ||

| Djedhotepre Dudimose II | T 7:13 |

There is reason to see the rulers in the above lists as being in three consecutive contemporary groups (that is, not only vertical but also three sequential horizontal groups in time).

- One group would be an early group that may have ruled during the terminal phase of the Twelfth Dynasty, beginning during the reign of Amenemhet III. Several of these rulers would be related to those last kings who may have had more descendants from secondary wives or concubines than we are aware. It has been noted a number of times by authors that there is clearly some filiation between the Twelfth and the Thirteenth Dynasties.

- A second group of rulers is midway through the list and contains kings known to have built pyramids. Therefore, they would follow soon after the pyramid built by Amenemhet III.

- Then a final group of reasonably strong kings exists who would have preceded the collapse (or Exodus).

Group 1: Kings Who Ruled during the Terminal Phase of the Twelfth Dynasty: Sub-Administrations

List 1

On List 1 (see table 3), we have 4 kings that appear to have filiation with Amenemhet III and IV10 (see table 4). These kings may well have been in sub-administrations at the terminal portion of the Twelfth Dynasty, concurrent with A III and A IV.

Table 4. Four kings who may have a filiation with Amenemhet III and IV from List 1 (see table 3).

| Ruler | Length of Reign |

|---|---|

| Sekemre Khutowe Amenemhet- Sobekhotep I | ≤ 3 years |

| Sekhemre Amenemhet Sonbef | 5 years (?) |

| Nikare (?) | 1 year (?) |

| Sekhemre Amenemhet V | 3–4 years |

List 2

Several kings on List 2 (see table 3) may be attributed to this period (the terminal phase of the Twelfth Dynasty); but because the mainstream belief is that of a completely consecutive list, most authors place them in a different period. The following is a brief discussion of these kings (see table 5).

Table 5. Kings from list 2 (see table 3) who may belong to the terminal phase of the Twelfth Dynasty.

| Ruler | Length of Reign |

|---|---|

| Renseneb | 4 months |

| Awibre Hor | [. . . and] 7 days11 |

| Sekhemrekhutawy Khabau | 3 years (?) |

| Djedkhepereu | 2 years (?) |

| Sedjefakare Kay Amenemhet VII | 6–7 years (?) or 3 years (?) |

Renseneb (Amenemhet) is the first king from list 2 who can be identified as ruling during the terminal phase of the Twelfth Dynasty. (His name suggests a descendant of an Amenemhet, who here could still well be A III or IV.) He reigned four months.

Another ruler who can be placed at this time is Awibre Hor (T 6:17). He appears to be the father of two more kings, and his burial was in a shaft in the NE corner of the pyramid of A III, as was one of his daughters. His canopic vessels were sealed with the name Amenemhet (III). John Rose (1985, 60–67) associates this name with both the Twelfth Dynasty and the Thirteenth. Rose suggests that Awibre Hor’s burial at Dahshur, which is associated with the pyramid of A III, may indicate that he is a brother or son of A III (dying early) and may be represented by the name Ameres in Manetho’s list of Twelfth-Dynasty kings. Awibre is only known to have reigned for “[. . . and] 7 days” from the latest reading of the Turin Canon (Ryholt 2004, 135–155).

Other rulers of this period are Sekhemrekhutawy Khabau, son of Awibre Hor. He reigned three years (?). Djedkhepereu, brother of Khabau, reigned two years (?). He is followed by Sedjefakare Kay Amenemhet VII (mentioned above and possibly also contemporary) who reigned 6–7 years (?) or three years (?) (uncertainty exists).

Each of these kings may also have served in a sub-administration during the terminal phase of the Twelfth Dynasty, and their short reigns may be indicative of short appointments rather than turbulence. One of the reasons for saying this is that two kings later is Khendjer, who is known to be contemporary with vizier Ankhu, suggesting that Khendjer followed at Memphis very soon after the termination of the Twelfth-Dynasty kings, if not straight after. The kings before also show some evidence of ruling earlier at Memphis.

At this spot in the Canon, we have information that gives clues to the ongoing chronology; that is, Vizier Ankhu served under Khendjer and several of the following kings, and some evidence would suggest that Ankhu’s daughter Senebhenas was consort to Wepwawethotep. Wepwawethotep was most likely the mayor of the Fifteenth Upper Egyptian nome (Grajetzki 2016, 111) and a relative of Queen Aya; so that Aya was also a close relative of Ankhu’s family and queen to Sekhemre Khutowe Sobekhotep 1 (T 6:5).12 However, Aya’s exact time of reign is not known but appears to have been contemporary with Ankhu’s daughter. Ankhu himself is believed to be the son of Vizier Zamonth who served under Amenemhet III (T 5:25).

List 3

The idea that the pharaohs in list 3 (see table 3) followed sequentially has blinded the possibility that the first two pharaohs of this list could have been early. Instead, they are assumed to be at the end of the independent reigns of the Thirteenth-Dynasty kings. However, since Wahibre Ibiau reigned 10 years and 8 months, and his successor Merneferre Ay reigned 23 years, 8 months, and 18 days, it appears this was a moderately stable period for this line in Thebes, who overall are associated with the south and Thebes.

A scarab of Wahibre Ibiau was found at Byblos. Using scarabs, some have argued that he was the last Thirteenth-Dynasty pharaoh cited there. But that claim assumes that the sequential arrangement of the king list at that point is proven; it is not, and that is the very point of contention. Single scarabs without significant other details of context and synchronisms give little certainty in deciding issues of sequence, as proposed. Therefore, one has to conclude that it neither affirms nor denies the suggested arrangement here put forward; whereas the other Thirteenth-Dynasty kings’ names found at Byblos have synchronistic associations.

Moreover, Merneferre appears to have built a pyramid, and therefore would partly fit with the next group of pyramid builders. This may suggest that Merneferre could have begun reigning concurrently with the Twelfth Dynasty. Later, he could have taken rule as one of the first sole rulers of the Thirteenth Dynasty after the collapse of the Twelfth (he is believed to have ruled the whole land for at least part of his reign). This is an idea that should be seriously considered. Further discussion of this time in the south will be re-addressed further on.

Group 2: The Pyramid Builders—Middle of the Lists

List 1

Ameny Qemau, who appears as fifth on the revised list but was originally at 6:13 as Swadjkare Ameny Qemau,13 built a pyramid at Dahshur. The burial chambers had similarities to that of A III. Recently, a second pyramid of Ameny Qemau was excavated in Dahshur close to Sneferu’s Bent Pyramid (Phillips 2017, 7–8). While there is debate, Ryholt (1997, 214, §3.3.2) believes that the name Ameny Qemau is a filiative nomen which means “Qemaw,” “Son of King Ameny.” He identifies Qemau’s father as Sekhemre Amenemhet V (the previous king) and argues that the next three kings are Qemau’s sons, reigning after him. The early place of Ameny Qemau and the relation of his son Hotepibre Qemau Siharnedjheritef with the Ebla king Immeya suggests the possibility that Ameny Qemau could be an earlier king than Amenemhet V.

Because Hotepibre Qemau Siharnedjheritef’s name has been found at Ebla as a contemporary with Immeya, he would then also be contemporary with or just slightly before the Byblos king Yakin-el, who himself was contemporary with Sehetepibre (T 6:12 on the first list; see table 3). After Siharnedjheritef, Iufni, his brother, reigned. Finally, Seankhibre Ameny-Intef Amenemhet VI reigned. So, the category of pyramid builders embraces a family dynasty of three generations, each having short reigns.

List 2

In the middle of List 2 (see table 3), two kings appear who are said to have built pyramids. As such, I would suggest they are close in time to Ameny Qemau. The first of these kings is Userkare Khendjer (T 6:20), who built at Sakkara. Khendjer, as mentioned previously, had a vizier Ankhu, who was also known to be vizier to Sekhemre Khutowe Sobekhotep I (T:6:5), and some speculate other XIIIth-Dynasty kings.

Khendjer’s reign is not certain, but a minimum reign is given as three or four years, three months, and five days on two control notes on stone blocks of his unfinished pyramid (Ryholt 1997, 193).14 He probably reigned at Memphis. Although his reign was short, he clearly was around long enough and important enough to be able to build a pyramid. The reason for the short reigns of so many Thirteenth-Dynasty kings has not been adequately explained, but several reasons have been suggested. The claim that the shorter reigns occurred just because it was a disturbed period, while easily suggested, is, in fact, speculative.

The second king in the middle of List 2 (see table 3) who built a temple is Smenkhkare Imyremeshaw (T 6:21). This latter king is known from two giant statues which were probably originally in the temple at Memphis (where he most probably ruled). Imyremeshaw is believed to have built a pyramid at Memphis, which is speculated to be the unfinished pyramid next to Khendjer in Sakkara, so identified by Albright (1945, 15).

List 3

In List 3 (see table 3), we return to Merneferre who with his long reign may well have been contemporary in the latter part of his reign with several of the other XIIIth-Dynasty pyramid builders mentioned above, or perhaps just before them. He also is said to have built a pyramid. We will later readdress this king.

Although these middle-of-the-lists kings who built pyramids are mostly seen to have short reigns, their ability to build their own pyramids would be logical if they were born during the end of the Twelfth Dynasty and were in some relationship to the last kings of that dynasty.

Group 3: Reasonably Strong Kings Preceding the Collapse

As discussed earlier, there is reason to believe that the collapse (as some see it) or the Exodus (as others see it) can be identified in three sites in the Turin Canon, a reason why I have suggested three contemporary lines of kings, and that the three sites are not contradictory but complimentary.

Let us then examine these in more detail.

List 1

Here, I point to Courville’s (1971, 1:118–129) pick where he cites the name ‘Koncharis’ from the Sothis List: a list that is usually spurned by most Egyptologists. However, he points out some significant features: (a) This list seems to refer to dominant pharaohs, leaving out non-dominant names. (b) It gives a series of names where the Twelfth Dynasty is mentioned giving alternate Ramesside names to the kings of that dynasty (these names were used hundreds of years before the Nineteenth-Dynasty Rameses). (c) One name Koncharis is placed before the clear names of the Hyksos kings, which Courville understandably then suggests is the pharaoh before and during the Exodus.

Courville (1971, 1:127) reasonably equates the Hellenised Koncharis to the Egyptian pharaoh Kha-ankh-re.15 Now, not a lot is known of this pharaoh, but Davies (1981, 22) has documented a statue of that king, as previously mentioned: a headless black granite statue. On the front of the statue is a prenomen and nomen, but beneath the feet, a prenomen is effaced which could be Khaneferre or Khahotepre (the latter is more likely on grounds of filiation). Davies’ discussion, however, has some ambiguity, as already stated. Moreover, as earlier stated, Siesse and Connor (2015) have argued on stylistic grounds that Khaankhre’s statue indicates a reign after Khaneferre, which again would suggest that Khaankhre also took the name of Khahotepre (or the reverse) after annexing another administration as the dominant pharaoh.

In the original presentation of the Turin Canon by Ibscher-Farina (as presented by Albright [1945, 14]), Khaankhre is presented as “Sebek-ḥatpe son of Mant-ḥatpe,” or, as it would later be written, “Sobekhotep son of Montuhotep.”16 Gardiner (1961, 440) presents him as “Rē’?-Sebek[ḥot]pe (I?), son of Nen(?).” But these additions do not appear in later presentations.

If List 2 (see table 3) is parallel, Sekhemre Sewadjtawy Sobekhotep III17 is significant as a close contemporary. Khaankhre18 and Neferhotep I19 are the only other names in the Turin Canon of this period stating parentage, which may add a suggestion of contemporaneity, as we also find in the seals of that period. All this raises the question of the filiation between Sobekhotep II (here Khaankhre) and Sobekhotep III. Sobekhotep III may be a brother or very possibly a father of Sobekhotep II. If so, an added drama is brought into the last days of the independent XIIIth dynasty; for it appears that the throne could have been usurped from Sobekhotep III by Neferhotep I. Was it then usurped back after the reign of Khaneferre20 by Sobekhotep21—also Khaankhre!—before the collapse (Exodus)? Of course, this remains speculation.

Both Khahotepre and Khaankhre had the birth name “Sebek hotep.” The only other known name of Khahotepre is the throne name “Kha-hotep re.” Apparently, Khahotepre has no known Horus name, and few artifacts are known: several scarabs, one from Abydos, one from the early part of Middle Bronze Jericho; a small statuette; and an unpublished stele found in Abydos which is now in the Grand Egyptian Museum. Did Kha-ankhre therefore also take the name Kha-hotepre? One of his variant birth names is Sobek Ra hotep.

But Kha-ankhre also has a Golden Horus name—Kau netjeru (“the sustenance of the gods”), a Nebty name—Djed kau (“stable of appearance”), and most significantly a Horus name—Sema-tawy (“the one who has united the two lands”)—the same name as the great unifier of the Eleventh Dynasty Mentuhotep II. And, Kha-ankhre appears to be the first king to use that name since Mentuhotep II some 250 years before, which lends credibility to the suggestion that he took action to be in control of Egypt overall.

Kha-ankhre also has a red granite altar found at Thebes which dates to the same period as a red granite, sixty-ton, stolen sarcophagus found at Abydos Mountain. Although the sarcophagus belongs to a “Sobekhotep,” it was not being used by its original owner. It is currently believed that the sarcophagus and an associated tomb belong to Khaneferre Sobekhotep IV, the other sarcophagus to Neferhotep I. Presently, this is totally speculative, but it is a reasonable suggestion. However, the sarcophagus and tomb could also rather involve Khaankhre (Sobekhotep II) and Sobekhotep III. Experts hope further findings will clarify the situation.

Khaankhre’s name alone in the appropriate place befitting the Exodus in the Sothis List, his Horus name, Khahotepre’s scarab at Jericho, and Khaankhre’s name appearing in the Turin Canon close to the time of Egypt’s collapse on the parallel re-aligned lists all lend some weight to the above suggestions. Although it may be only circumstantial, the names Khahotepre and Khaankhre, despite being wide apart in Turin, are listed together sequentially on the Karnak List (46 and 47—otherwise alternate 41 and 40). Both then were significant to Karnak. Again, of interest, Siesse and Connor (2015, 227–47) have placed these two kings together.

List 2

Albright (1940, 26; 1945, 15) and Säve-Söderbergh (1951, 53–71) identified the collapse of Egypt soon after the reign of the kings from Sobekhotep III through to Khaneferre Sobekhotep IV (T 6:24–T 6:27 on List 2; see table 3). As previously mentioned, I have suggested Khahotepre22 followed because of his scarab in Jericho.

Ryholt (1997, 73, 232–233) has placed Merhotepre Sobekhotep (therefore V) just before Khahotepre Sobekhotep (therefore VI). It is of interest that in the genealogy of El Kab officials of that period (viz. Renseneb and Sobeknakht II) and in the Karnak Judicial Stele, a ‘Merhotepre’ occurs very soon in time after kings Khasekhemre Neferhotep I (T 6:25) and Khaneferre Sobekhotep IV (T 6:27). Davies (2010, 223–240) has suggested Merhotepre Ini (T 7:4) based on a purely sequential interpretation.

From the genealogy of the Judicial Stela from Karnak (Cairo Museum JE 52453) and the genealogy in the tomb of Sobeknakht II (Davies 2010), Aya, governor of El Kab, is placed in the second generation from Sobekhotep IV23 and in the first year of Merhotepre. Then, in the second generation after Aya, we meet Sobeknakht I, who was appointed in the first year of the Sixteenth-Dynasty king Nebiryrau Sewadjenre I, a possible 23 years into that dynasty.

With many Egyptologists, this particular place in the Turin Canon (List 2) has been a favorite place of contention for Egypt’s collapse (most do not relate it to the Exodus). The correlation with the Byblos kings (with Neferhotep I) has strengthened that conviction for many. If List 2 were contemporary with List 1 (see table 3), a further correlation then would be evident, as one king on each of these lists can be correlated with these Byblos kings—Sehetepibre III (List 1; T 6:12) and Neferhotep I (List 2; T 6:25) (see table 1).

List 3

List 3 (see table 3) ends with a further identification of an Egyptian ruler who reigned during the collapse. Most recently, but not alone, David Rohl (1995, 280–81) has suggested Dudimose, who he correlates with Manetho’s Tutimaios. However, there are two Dudimoses and some differences of opinion as to their order. The order here given is Djedneferre Dudimose I (T 7:12) and then Djedhotepre Dudimose II (T 7:13). They are at the end of this suggested third list, are recognized as kings in the south, and are the last kings before the Hyksos.

The immediate reaction to these different placements of Egypt’s collapse is to believe that one may be correct while the others are incorrect. But, taking into account the known ancient way of placing contemporary dynasties in sequential order, I would suggest that each of these identifications have merit and that all these kings can be placed at the time of the collapse (Exodus).

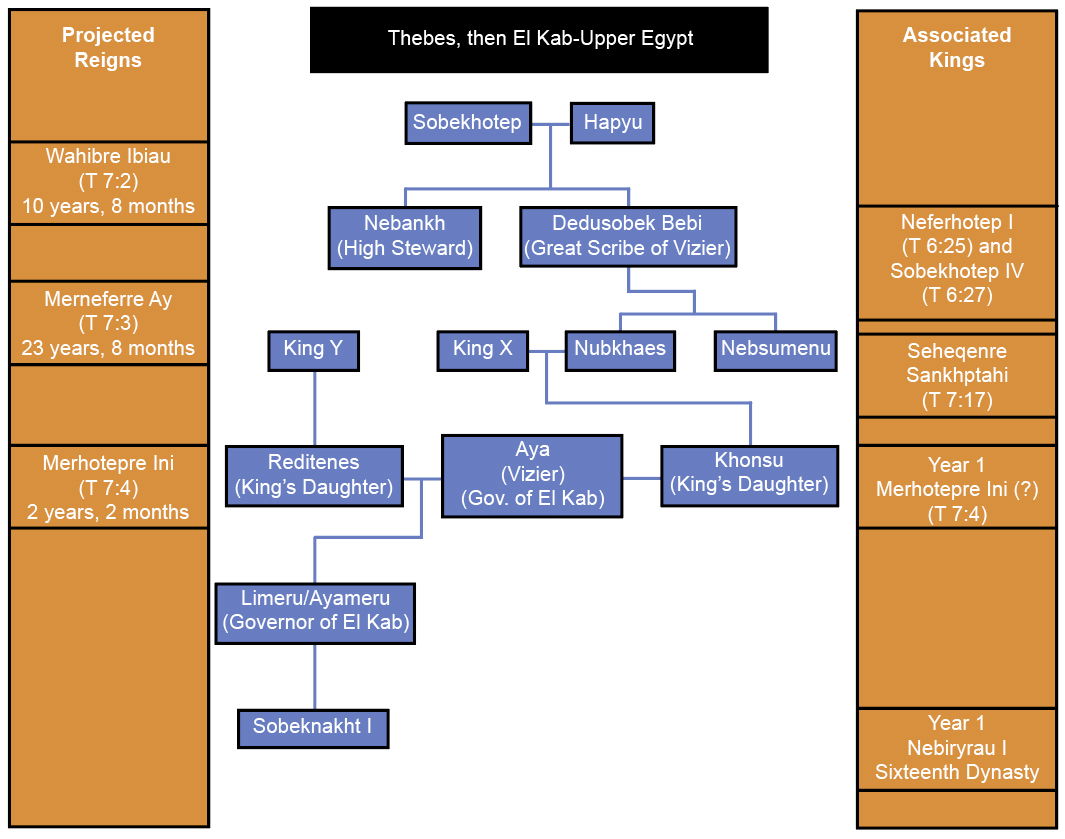

It is more difficult to argue for the contemporaneity of List 3. Instructive in regards to List 3 are the details of a Theban family presented by Wolfram Grajetzki (2016). Here, we have two brothers Nebankh and Dedusobek, sons of a certain Sobekhotep and wife Hapyu, who served under Neferhotep I (T 6:25) and Sobekhotep IV (T 6:27). Nebankh served as a royal sealer/high steward, and Dedusobek served as a great scribe of the Vizier. These brothers were contemporary with Senebi, treasurer of Neferhotep I and Sobekhotep IV. Follow then their children, most particularly Nebsumenu (scribe of the king’s document) who appears to be contemporary with Thirteenth-Dynasty king Seheqenre Sankhptahi (T 7:17).24 (See fig. 1.)

Fig. 1. Family tree of Sobekhotep and Hapyu shown with contemporary Egyptian rulers.

These known relationships produce significant challenges to the purely sequential interpretation! Nebankh and Dedusobek are clearly in service under Neferhotep I and then his brother Sobekhotep IV (List 2). But, in the next generation, we find Dedusobek’s son Nebsumenu. Nebsumenu’s Stela is associated with King Seheqenre Sankhptahi several kings down the list (possibly T 7:17, but Ryholt [1997, 72n214, 73 table 17] places him at 8:25). He, therefore, would be closely associated in time with Merhotepre Sobekhotep V (reign length—three years) and Khahotepre Sobekhotep VI (T 7:1; reign length—four years, eight months). This is the place of the collapse on the reckoning of Albright (1940, 26; 1945, 15) and Säve-Söderbergh (1951, 53–71). Seheqenre Sankhptahi is believed by Ryholt (1997, 79, 405, 454) to have ruled at Memphis (as possibly indicated by the name), but if so would most likely at that moment have been the last native king to rule in that city before takeover by the Hyksos.

One generation later, we find Governor Aya married to Nebsumenu’s niece Khonsu (styled “king’s daughter”) as well as Reditenes (daughter of an unknown king). He is installed as governor in the first year of Merhotepre. This could be Merhotepre Sobekhotep V, but considering the chronological position, this is unlikely. This leaves Merhotepre Ini (List 3; T 7:4), who reigned for only two years, two months, and nine days following Merneferre Ay (T 7:3).

Ryholt (1997, 192) has speculatively suggested that Merhotepre Ini was the son of Merneferre Ay and that Reditenes was Merhotepre’s sister. Her marriage to Governor (vizier) Aya gave Merhotepre further political influence. Now Merneferre Ay (T 7:3) reigned for 23 years before Merhotepre Ini (T 7:4), and, as such, his reign would have significantly overlapped both Sobekhotep IV (T 6:27) and much of the reign of Neferhotep I (T 6:25).

Before Merneferre (T 7:3) was Wahibre Ibiau (T 7:2), who reigned for 10 years and eight months. Such a reign length would put Ibiau back close to Khendjer (T 6:20) in List 2, who we have already established reigned very soon after the collapse of Dynasty 12. I have projected the possible tie of these reigns on the left of the diagram above (see fig. 1). All these facts give us reason to claim that the three suggested lists (see table 3) were largely contemporary and that the last kings of each list were close to the collapse of Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period—here claimed to be the time of the Exodus.

Sobeknakht I (Governor) was appointed during year 1 of Nebiryrau I, the sixth king of the Sixteenth Dynasty. The Sixteenth Dynasty appears to have run for around 22 years under the previous rulers and is likely to have been concurrent with the El Kab governor Limeru (Ayameru). Based on the chronological suggestions in this discussion, the Sixteenth Dynasty started in Thebes as the Thirteenth Dynasty at Thebes faded. This would suggest that the kings listed after Merhotepre Ini (T 7:4) were very ephemeral, unless the actual cities of their rule are not fully known, and the two dynasties ran briefly parallel.

Lacking in much of the discussion of this period is the fact that an ‘Asiatic’ population was present in the eastern Delta region (Goshen) at this period (as found at Tell el-Dabʽa) which was followed by a settlement hiatus before a new group of ‘Asiatics,’ the ‘Avaris’ Kingdom appears. The first group of Asiatics is likely the Israelites, and the hiatus indicates the Exodus, which would be followed by the influx that would herald the Fourteenth and Hyksos Sixteenth Dynasties. However, as most authors do not equate this period with the Exodus, such discussion does not eventuate. But this would rule out an immediate concurrence of the contemporary Thirteenth-Dynasty rulers and the Hyksos (unless we consider the Turin kings after T 7:13 as also being included in the Thirteenth Dynasty, but this is not settled). The influx of the Hyksos would follow soon after.

Table 6 illustrates the Theban Sixteenth Dynasty.

Table 6. Theban Sixteenth-Dynasty rulers and their reign lengths. Data from Ryholt (1997, 202).

| Theban Ruler | Reign Length |

|---|---|

| Unknown (lost in lacuna in Turin Canon) | 1 year |

| Sekhemre Sementawy Djehuty | 3 years |

| Sekhemre Seusertawy Sobekhotep VIII | 16 years |

| Sekhemre Seankhtawy Neferhotep III | 1 year |

| Seankhenre Mentuhotepi | 1 year |

| Sewadjenre Nebiryrau I | 26 years |

| Neferkare Nebiryrau II | 1/4 year (?) |

| Semenre | 1 year (?) |

| Seuserenre Bebiankh | 12 years |

| Sekhemre Shedwaset | 1/4 year (?) |

| Unknown (Five kings lost in lacuna in Turin Canon) | 6 years (?) |

The kings from T 7:5 to T 7:13 have generally been considered Thirteenth-Dynasty kings. King T 7:13 has been transcribed “Mose” by Gardiner (1961, 441) and “Dudimose” by Rohl (1995, 280). Archaeologists Kim Ryholt (1997, 201, 2.7.3.4), Darrell Baker (2008), Aldan Dodson and Dyan Hilton (2004, 100–101) ascribe the last two of these, viz. Djedneferre Dudimose I and Djedhotepre Dudimose II, to the Sixteenth Dynasty; in which case, they should be placed at the beginning of the above list. However, von Beckerath (1999), Thomas Schneider (2006, 180), and Detlef Franke (1994, 77–78) assign them to the end of the Thirteenth (this may not be as contradictory as first suggested).

Kim Ryholt (1997, 402) believes that the last Dudimose (that is, Djedhotepre Dudimose II) had to negotiate with the invading Hyksos: a point I myself have suggested, which indicates that he was a subsidiary king in the south at the time of the Exodus and not the dominant biblical pharaoh. David Rohl (1995, 280–281), taking a different angle, has argued that he may be the pharaoh of the Exodus but does not differentiate between Dudimose Djedneferre and Djedhotepre.

The overall idea that comes through with all these variant opinions is that the Dudimose kings had to be before the Sixteenth-Dynasty kings listed above, wherever they had their rule and despite the differences, and that they fit with a period close to Egypt’s collapse: here held to be the Exodus. This then demands the exit of Israel at this point of collapse and the invasion of the Hyksos soon after (the “obscure race” of Manetho [Josephus 1974, 162–163, C. Ap. 1.14; see Rohl 1995, 280–81]).

Clay sealings found at Edfu of both Thirteenth Dynasty Sobekhotep IV and Hyksos king Khyan have resulted in some claiming contemporaneity of these two kings; but, with the nature of accumulation of clay sealing, such is not guaranteed. Both Robert Porter (2013, 75–80) and Alexander Ilin-Tomich (2014, 149–152; 2016, 7) have argued that such a conclusion is not justified. Nevertheless, it is certain that these two kings—the Thirteenth-Dynasty king and then the following Hyksos king—were not far apart in time. Such a succession fits perfectly with the Exodus being allocated in this position.

In a previous discussion (Osgood 2020, 286, 191), I placed Mayebre Sheshi, the Hyksos king, as the overlord of Eglon King of Moab (Judges 3:12–30) at the time of the MB IIB Palace at Jericho, where his scarab was found and scarabs of Egyptian officials were present. This event is datable to circa. 1300 B.C. Mayebre Sheshi here appears and may also be related to Nehesy Aasehre of the early Fourteenth Dynasty.

On the basis of scarab types found in Palestine and which were arranged by Tufnell (1984, 172), I have placed Seuserenre Khyan before Meruserre Yakubher; both prior to Sheshi; and after 1400 B.C. after the settlement of Israel in the Holy Land. This places Khyan apart from, and a short time after Sobekhotep IV. The latter can, based on these previous arguments, be dated to circa. 1450 B.C., immediately before the Exodus. Against the Bible’s record, Khyan may be considered a candidate for Agag I in the later days of Moses who was mentioned just before Israel’s invasion (Numbers 24:7), despite the lack of name correspondence.

A door jamb found by Bietak (1996, 113) in a Hyksos horizon at Tell el-Dabʽa has the name of a Hyksos king Sakir-Har (Aasehre). He has been suggested to have reigned before Khyan and after Salitis; although, his exact time of reign is still not settled. So, a sequence of Salitis–Sakir-Har–Khyan is at present held. And, as the reader may infer from the above discussion, I have then suggested that next in order is Meruserre Yakubher and then Sheshi, who I have dated around the years 1300 B.C., with Nehesy of the Fourteenth Dynasty at Avaris or Xois as Sheshi’s possible son. This then allows that soon after the earlier mentioned hiatus at Tell el-Dabʽa—which I have suggested signals the departure of the Israelites—Egypt was invaded; and these five abovementioned kings (Salitis, Sakir-Har, Khyan, Muruserre Yakubher, and Sheshi) occupied the time period in Egypt of 1446–1300 B.C.25

Just before the conquest of Israel in 1406 BC, Balaam spoke of a powerful king Agag I who would be superseded in power by a later King of Israel (Numbers 24:7). He called Amalek, the “first of the nations.” The Hebrew word translated “first” means “head” of the nations (Numbers 24:20). Within the context, this title demands that Amalek was now in charge of the devastated Egypt as a powerful king. For this reason, I have suggested that this individual may be Khyan and that 1406 B.C was during his reign.

Conclusion

A case has been presented that the Thirteenth (XIIIth) Dynasty, as reflected mainly in the Turin Canon, allows the contemporaneity of several lines of kings. These first began as subsidiary administrations during the time of Amenemhet III of the Twelfth Dynasty. Afterward, these administrations would develop into contemporary lines of kings who would rule for a period close to 30 years after the collapse of the Twelfth Dynasty and until a period of a collapse of Egypt’s general integrity: a moment corresponding to a hiatus in the occupation of Pi-Rameses/Avaris and matching the moment of Israel’s departure from Egypt—the Exodus.

After invasions from the east, this collapse soon led to the establishment of Asiatic/Hyksos dynasties reigning in Lower Egypt and a Theban (Egyptian) Sixteenth Dynasty in Upper Egypt, the latter of which may or may not have been concurrent with a terminal phase of the Thirteenth Dynasty. These conclusions rule out any certain Hyksos reign beginning before Israel’s departure after Level G1 at Tell el-Dabʽa and imply that the beginning of their reigns started with Level F of Tell A of Tell el-Dabʽa.

The archaeological horizon in Egypt is MB IIA, but this author does not make an exact correlation of this horizon with the contemporary period in Palestine, nor, in fact, of the general Levant. Ethnic culture also must be a factor in the interpretation of archaeological horizon alignment here.26

References

Albright, William F. 1940. “New Light on the History of Western Asia in the Second Millennium B.C. (Continued).” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 78 (April): 23–31.

Albright, William F. 1945. “An Indirect Synchronism between Egypt and Mesopotamia, cir. 1730 B. C.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 99 (October): 9–18.

Baker, Darrell D. 2008. The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Vol. 1. Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300–1069 BC). London, United Kingdom: Stacey International.

Bietak, Manfred. 1996. Avaris: The Capital of the Hyksos. Recent Excavations at Tell el-Dabʽa. Raymond and Beverly Sackler Foundation Distinguished Lecture in Egyptology 1. London, United Kingdom: British Museum Press.

Courville, Donovan A. 1971. The Exodus Problem and Its Ramifications: A Critical Examination of the Chronological Relationships between Israel and the Contemporary Peoples of Antiquity. Vols. 1 and 2. Loma Linda, California: Challenge Books.

Davies, W. Vivian. 1981. A Royal Statue Reattributed. British Museum Occasional Paper, no. 28. London, United Kingdom: British Museum, Department of Egyptian Antiquities.

Davies, William Vivian. 2010. “Renseneb and Sobeknakht of Elkab: The Genealogical Data.” In The Second Intermediate Period (Thirteenth–Seventeenth Dynasties): Current Research, Future Prospects. Edited by Marcel Marée, 223–240. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta. Vol. 192. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters Publishers.

Depuydt, Leo. 1993. “The Date of Piye’s Egyptian Campaign and the Chronology of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 79, no. 1 (October): 269–274.

Dodson, Aidan, and Dyan Hilton. 2004. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London, United Kingdom: Thames and Hudson.

Franke, Detlef. 1994. Das Heiligtum des Heqaib auf Elephantine: Geschichte eines Provinzheiligtums im Mittleren Reich. Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altägyptens 9. Heidelberg, Germany: Heidelberger Orientverlag.

Gardiner, Sir Alan. 1961. Egypt of the Pharaohs: An Introduction. London, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Grajetzki, Wolfram. 2016. “A Thirteenth Dynasty Family.” Ancient Egypt 17, no. 2 (October/November): 38–43.

Ilin-Tomich, Alexander. 2014. “The Theban Kingdom of Dynasty 16: Its Rise, Administration and Politics.” Journal of Egyptian History 7, no. 2 (November): 143–193.

Ilin-Tomich, Alexander. 2016. “The Second Intermediate Period.” In UCLA Encylopedia of Egyptology. Edited by Willeke Wendrich, Jacco Dieleman, Elizabeth Frood, Wolfram Grajetzki, and John Baines. Los Angeles, California: University of California.

Josephus, Flavius. 1974. The Works of Flavius Josephus. Translated by William Whiston. Vol. 4. Antiquities of the Jews: Books XVIII–XX; Flavius Josephus Against Apion; Concerning Hades; Appendix; Index. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.

Osgood, John, 2020. They Speak with One Voice: A Correlation of the Bible Record with Archaeology. Bunjurgen, Queensland, Australia: Self-published.

Petrie, Sir William Matthew Flinders. 1917. Scarabs and Cylinders with Names: Illustrated by the Egyptian Collection in University College, London. Warminster, Wiltshire, England: Aris and Phillips Ltd.

Phillips, J. Peter. 2017. “From the Editor.” Ancient Egypt Magazine 17, no. 6 (June/July).

Porter, Robert M. 2013. “The Second Intermediate Period According to Edfu.” Göttinger Miszellen 239:75–79.

Rohl, David M. 1995. A Test of Time. Vol. 1. The Bible—From Myth to History. London, United Kingdom: Arrow Books.

Rohl, David M. 2007. A Test of Time. Vol. 3. The Lords of Avaris: Uncovering the Legendary Origins of Western Civilisation. London, United Kingdom: Century Publications.

Rose, John. 1985. The Sons of Re: Cartouches of the Kings of Egypt. Cheshire, England: JR-T.

Ryholt, Kim. 1997. The Political Situation in Egypt During the Second Intermediate Period: C. 1800–1550 B.C. Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications 20. Charlottenlund, Denmark: Museum Tusculanum Press.

Ryholt, Kim. 2004. “The Turin King-List.” Ägypten und Levante/Egypt and the Levant 14: 135–155.

Säve-Söderbergh, T. 1951. “The Hyksos Rule in Egypt.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 37 (December): 53–71.

Schneider, Thomas. 2006. “Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period.” In Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton, 168–196. Handbook of Oriental Studies, sec. 1. Vol. 83. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Shea, William H. 1985. “Sennacherib’s Second Palestinian Campaign.” Journal of Biblical Literature 104, no. 3 (September): 401–418.

Siesse, Julien, and Simon Connor. 2015. “Nouvelle Datation Pour le Roi Sobekhotep Khâânkhrê.” Revue d’Égyptologie 66: 227–247.

Smith, Henry B. Jr. 2014. “Archaeology’s Lost Conquest.” Answers Magazine, 9, no. 3 (July–September): 80–84.

Tufnell, Olga. 1984. Studies on Scarab Seals. Vol. 2. Scarab Seals and Their Contribution to History in the Early Second Millennium B. C. Wiltshire, England: Aris and Phillips Ltd.

von Beckerath, Jürgen. 1999. Handbuch der Ägyptischen Königsnamen. 2nd ed. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien 49. Mainz, Germany: Verlag Philipp Von Zabern.

Yvanez, Elsa. 2010. Rock Inscriptions from Semna and Kumma: Epigraphic Study. Khartoum, Sudan: SFDAS.