The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

This paper first addresses three methods of aligning the Egyptian and biblical timelines, with comments on why the Courville system is untenable. Second, it discusses how the Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties of Egypt could have reigned simultaneously. Third, it shows that radiocarbon dating does not support Porter’s claim that the Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties could not have reigned concurrently. Finally, Bayesian mathematics should not be used in radiocarbon dating, as it produces biased conclusions.

Keywords: Egyptian chronology, biblical chronology, synchronizing timelines, radiocarbon dating, Sixth Dynasty, Twelfth Dynasty, Bayesian mathematics

Introduction

In this further discussion on the placement of the Exodus in Egyptian history, I will first address the methodologies used by Porter (2022a, b), Osgood (2022) and myself in aligning the biblical and Egyptian timelines. Then I will question Osgood’s belief in the chronologist, Courville. After that, I will show how the Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties could have ruled at the same time, as Osgood and I believe. Finally, I will examine Porter’s claim that radiocarbon dating supports his contention that the Sixth Dynasty could not have run concurrently with the Twelfth; and will show that he is incorrect.

The Methodology of Shortening the Egyptian Timeline

Both Porter (2022a, b) and Osgood (2022) have chosen to align the timelines by taking a certain number of years out of the Egyptian timeline to shorten it. They have used different ways of calculating this, and I showed in my first comments article how they each did it (Habermehl 2022). The weakness of their respective methods is that they have essentially decided how and where to remove these years in order to attempt to make biblical alignments that work.

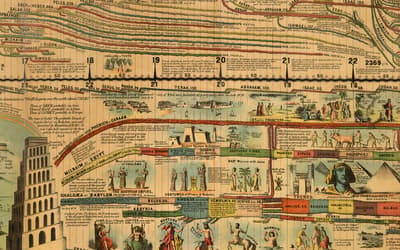

I suggest here that we should work on this subject from the opposite direction. First we should determine what biblical people and events correlate to what points in the Egyptian timeline. From those synchronizations the differences between the two timelines will then shake out. In my published chronological work I have set up Bible/Egyptian correlations including the following: Abraham = Beginning of First Dynasty; Joseph = Imhotep of Third Dynasty1; Exodus = End of concurrent Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties, with Pharaoh of Exodus = Amenemhat IV; Shishak = Amenhotep II (son of Thutmose III). Extensive arguments and evidences for these correlations are laid out in my published (Habermehl 2013, 2018a, 2023). Porter and Osgood do not agree with all of these correlations because they have used a different methodology and arguments.

The Courville Chronology

In 1970 Donovan Courville published an extensive two-volume work on the Exodus (Courville 1971). He espoused a system of rearranging the Egyptian Dynasties drastically based on claiming that various famines mentioned throughout Egyptian history had to have occurred at the same time. I have a problem with this because Courville’s unproven claim about the famines is shaky ground for reordering the dynasties. Also his method takes too many years out of the third millennium B.C. (Egyptian timeline), as I pointed out in my previous reply (Habermehl 2022). Osgood, however, chooses to subscribe to the Courville scheme.

Rather than go into detail here on the problems with Courville’s system, I recommend that readers see this online article by Vern Crisler, especially with respect to the end of the First and Second Dynasties (Crisler 2013). As Crisler says, “Courville’s original model of a first dynasty/third dynasty overlap is unworkable, given all the available evidence.” I consider that Crisler’s arguments on Courville are compelling.

How Could the Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties Have Reigned Concurrently?

This is a legitimate question to ask, because when we think of a pharaoh we think of a king who ruled over all of Egypt. Historians today interpret all known Egyptian information from the point of view of most dynasties laid out end to end (with some exceptions).

Porter claimed in his reply (Porter 2022b) that it was not possible for the Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties to have reigned at the same time. Osgood (2022) and I maintain that this is indeed possible; and that secular historians are incorrect in running these two dynasties consecutively. Historians also run the First Intermediate Period immediately after the Sixth Dynasty, and the Second Intermediate Period after the Twelfth Dynasty. However, Osgood and I are saying that there was only one Intermediate Period that followed the Sixth/Twelfth Dynasty period.

If two pharaohs were ruling at once, it would be most likely that the one would be more powerful than the other. In this case, the Twelfth-Dynasty pharaoh would have been the more powerful, because he ruled the Delta, where the Children of Israel were. Because of the political balance of the day, it would have been advantageous for the greater Twelfth-Dynasty pharaoh in Lower (north) Egypt to let Upper (south) Egypt appear to be a separate entity with its own Sixth-Dynasty pharaoh. This situation follows from the ancient concept of the two Egypts, north and south, a dichotomy that has been around from the beginning of Egyptian history to this very day. As an aside, Upper and Lower Egypt could have had pottery that differed in style (as noted by Porter) because of the distinctive cultural differences between the two parts of Egypt.

The two concurrently ruling pharaohs did not appear to live far apart. The Sixth Dynasty ruled from Memphis, about 15 miles south of modern Cairo. The Twelfth Dynasty ruled from its new city of Itjtawy (nobody knows for sure where this city is to this day, but historians believe it is in the Faiyum region) (Shaw 2003, 146). If so, the two pharaohs ruled from capitals approximately east-west of each other. Presumably this allowed the greater pharaoh to keep an eye on what the lesser pharaoh was up to!

With two dynasties ruling concurrently, it would have been made quite clear by the greater pharaoh what powers the lesser pharaoh had and did not have. All the pharaohs of both dynasties appeared to have had the right to build their pyramids in the Saqqara area (Edwards 1988, 176–177; 202–223), which would not have been far from the capital of either dynasty.

The historical sources constantly mention that the power of the pharaohs declined during the early Sixth Dynasty, while nobles became more powerful (Shaw 2003,106–107). It is likely that the Sixth-Dynasty pharaohs had less power than before because the Twelfth-Dynasty pharaohs were now ruling over them. Clearly we have to rearrange our ideas about the power balance with the Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties ruling at the same time.

The current secular timeline that runs these two dynasties and the two following intermediate periods in consecutive order complicates matters for determining the dating of the Exodus. It means that there are two secular dates for the Exodus, one about 2200 B.C. (Sixth Dynasty) and one about 1800 B.C. (Twelfth Dynasty) on the secular timeline (Habermehl 2013). Also those who have difficulty believing that the Ipuwer Papyrus refers to the Exodus stumble over the fact that some scholars date the original Papyrus to the end of the Sixth Dynasty, and some to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty (Habermehl 2018b). This disagreement among the scholars in itself inadvertently supports the concurrent Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties, and the Exodus at the end of both.

Radiocarbon Dating: What Does It Prove?

Porter (2022b) points to radiocarbon dating of samples from the Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties to support his claim that these dynasties could not have reigned concurrently. We need to scrutinize these radiocarbon dating results to see whether they actually offer proof of his assertion.

An examination of the S1 chart in the supplementary material of the Ramsey et al. (2010) paper referenced by Porter shows a lot of discrepancies in the sample dates of the various kings. For example, a sample in the chart from Khafra (Fourth Dynasty) is a real outlier—only 107 years! Obviously something is wrong there, as the authors indicate by showing it on a red bar. Djoser of the Third Dynasty has dates that vary widely (the last three are from the same sample): 2421, 3313, 4081, 4172, 4115. But the Third Dynasty reigned well before the Sixth, and two of Djoser’s dates are a lot younger than the Pepy I date of the Sixth Dynasty. So much for confidence in these radiocarbon dates.

Furthermore there is only one Dynasty Six sample listed (Pepy I, 3,979 yrs). Can we expect that only one radiocarbon date will give us any confidence in a chart full of discrepancies? From the point of view of testing procedures, we need an adequate number of samples to get results that mean anything, and we need results that are consistent.

But that is not all. These test results have all been subjected to manipulation by something called Bayesian mathematics. Gelman et al. (2013) offer a useful definition: “Bayesian statistics is a theory in the field of statistics based on the Bayesian interpretation of probability where probability expresses a degree of belief in an event. The degree of belief may be based on prior knowledge about the event, such as the results of previous experiments, or on personal beliefs about the event.” (Italics added.)

A subsection of Bayesian statistics called “OxCal” has been developed by Ramsey (2009) for applications like this in archaeology. Archaeologists have taken to the OxCal algorithm with enthusiasm, as is shown in the Ramsey et al. (2010) paper referenced above.

What this all means (unbelievably!) is that the prior belief that the Sixth Dynasty belonged to the Old Kingdom, and was older than the Twelfth Dynasty (Middle Kingdom), was fed into the radiocarbon dating calculations.

We might wonder what would happen if we had enough good Sixth-Dynasty radiocarbon dating samples, and then applied the Bayesian OxCal technique to them based on the prior belief that the Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties ran concurrently. We might get very satisfactory results from the point of view of running the two dynasties concurrently. Do I hear objections? I should hope so. Mathematical manipulation is not an honest way to prove a point.

In any case, we cannot say that current radiocarbon dating supports the classical beliefs about the Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties; and most certainly it does not prove that these two dynasties did not run concurrently.

Since this thread is about the place of the Exodus in Egyptian history, this might be a good time to remind readers that with the Sixth and Twelfth Dynasties running concurrently instead of consecutively, the Exodus occurred at the end of both. As noted earlier, this gives us two dates for the Exodus on the standard timeline used by archaeologists.

Indeed, I have wondered whether we would ever have picked out the anomaly of these two dynasties incorrectly placed end to end in the standard Egyptian timeline if the Exodus had not occurred. We might have wondered why Egypt collapsed twice in the same way only a few hundred years apart. But because of the biblical narrative we know that it is the catastrophe caused by the ten plagues preceding the Exodus that explains both of those collapses.

References

Bates, Gary, Robert Carter, Gavin Cox, and Keaton Halley. 2020. Tour Egypt. Powder Springs, Georgia: Creation Book Publishers.

Courville, Donovan A. 1971. The Exodus Problem and Its Ramifications: A Critical Examination of the Chronological Relationships Between Israel and the Contemporary Peoples of Antiquity. 2 Vols. Loma Linda, California: Challenge Books.

Crisler, Vern. 2013. “Egyptian Chronology and the Bible: The Pre-Patriarchal Era.” https://vernerable.files.wordpress.com/2008/10/egyptianchronology1.pdf.

Edwards, I. E. S. 1988. The Pyramids of Egypt. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books.

El-Aref, Nevine. 2013. “Old Kingdom Leather Fragments Reveal How Ancient Egyptians Built Their Chariots.” https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/9/40/69897/Heritage/Ancient-Egypt/Old-Kingdom-leather-fragments-reveal-how-ancient-E.aspx.

Gelman, Andrew, John B. Carlin, Hal S. Stern, David B. Dunson, Aki Vehtari, and Donald B. Rubin. 2013. Bayesian Data Analysis. 3rd ed. London, England: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

Habermehl, Anne. 2013. “Revising the Egyptian Chronology: Joseph as Imhotep, and Amenemhat IV as Pharaoh of the Exodus.” In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Creationism. Edited by Mark Horstemeyer. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship,

Habermehl 2018a. “Chronology and the Gezer Connection—Solomon, Thutmose III, Shishak and Hatshepsut.” Journal of Creation 32, no. 2 (August): 83–90.

Habermehl, Anne. 2018b. “The Ipuwer Papyrus and the Exodus.” In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism. Edited by John H. Whitmore, 1–6. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship.

Habermehl, Anne. 2022. “The Place of the Exodus in Egyptian History: Comments.” Answers Research Journal 15 (May 25): 121–123. https://answersresearchjournal.org/ancient-egypt/place-of-exodus-egyptian-history-comments-habermehl/.

Habermehl, Anne. 2023. “Synchronization of the Biblical and Egyptian Timelines.” Answers Research Journal 16 (November 18): 561–576. https://answersresearchjournal.org/ancient-egypt/synchronization-biblical-and-egyptian-timelines/.

Osgood, A. John M. 2022. “The Place of the Exodus in Egyptian History: Comments.” Answers Research Journal 15 (March 2): 21–23. https://answersresearchjournal.org/ancient-egypt/place-of-exodus-egyptian-history-comments/.

Porter, Robert M. 2022a. “The Place of the Exodus in Egyptian History.” Answers Research Journal 15 (February 16): 1–9. https://answersresearchjournal.org/ancient-egypt/place-of-exodus-egyptian-history/.

Porter, Robert M. 2022b. “The Place of the Exodus in Egyptian History: Reply # 1.” Answers Research Journal 15 (May 25): 125–127. https://answersresearchjournal.org/ancient-egypt/place-of-exodus-egyptian-history-reply-porter/.

Ramsey, Christopher Bronk. 2009. “Bayesian Analysis of Radiocarbon Dates.” Radiocarbon 51, no. 1 (18 July): 337–360.

Ramsey, Christopher Bronk, Michael W. Dee, Joanne M. Rowland, Thomas F. G. Higham, Stephen A. Harris, Fiona Brock, Anita Quiles, Eva M. Wild, Ezra S. Marcus, and Andrew J. Shortland. 2010. “Radiocarbon-Based Chronology for Dynastic Egypt.” Science 328, no. 5985 (18 June): 1554–1557.

Shaw, Ian. 2003. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.