Research conducted by Answers in Genesis staff scientists or sponsored by Answers in Genesis is funded solely by supporters’ donations.

Abstract

Who were the Hyksos? These enigmatic people are possibly important in biblical history, but their origin and interaction with biblical events have been questioned. Previously, they were thought to be foreign invaders who took advantage of a period of weakness to seize power in Egypt. The newly emerging paradigm is that they were insiders who staged a bloodless coup. The Hyksos ruled Egypt during the Fifteenth Dynasty and then were overthrown by the Eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian Pharaoh Ahmose. An interesting idea has been developed in recent decades that connects the Hyksos with the Bible’s Exodus account. This fascinating time in history was when much of northern (lower) Egypt was overtaken by foreigners (that many ancient sources say were Asiatic hordes from the east) known as the Hyksos, who are also confirmed by the archaeological record—perhaps the only time in the entire second millennium BC that the regional powerhouse of the time, Egypt, was dominated by a foreign power in this way. Some have recognized that the timing of this event may fit the aftermath of the biblical Exodus when Egypt was brought to its knees by the rapid succession of the ten plagues, including the death of every firstborn, the loss (exodus) of Egypt’s massive slave force, and the destruction of a large portion of their army (and most importantly their chariot cavalry) at the bottom of the Red Sea. The hypothesis espoused in this paper is that the Fourteenth Dynasty was comprised of foreigners who migrated to Egypt and, with a vulnerable Egypt following the events of the Exodus, took over the Nile Delta, which further weakened the native Thirteenth Dynasty. Then a few decades later, the Hyksos came from outside Egypt to take advantage of the unique power vacuum created by these events and easily conquered parts of Upper Egypt and even parts of Lower Egypt.

Keywords: Chronology; Hyksos; Exodus; Egypt; Israel; Levant; Amorites; Amalekites; Archaeology

The Recently Published Study at Tell el-Dabca

In July 2020, a study (Stantis et. al. 2020) was published which has questioned the historical narrative of the Hyksos peoples. Instead of invading and conquering Egypt, the new study claims that they had lived in the northern Nile Delta region for centuries, and opportunistically seized power when Egypt was involved in some type of domestic turmoil or disarray. By examining this study and using clues from the biblical text, can more light be shed on who the mysterious Hyksos were?

The July 2020 study centered around the human remains of people who had been buried in cemeteries in Tell el-Dabca, ancient Avaris (near modern-day Faqus). In order to broadly determine the ethnicity of the people who were buried there, strontium isotope (87Sr/86Sr) analysis of dental remains of 75 individuals who had been buried there was performed, although the remains are now housed in museums in Cairo, Egypt, and Vienna, Austria, not in situ. In addition to the strontium isotope analyses, archaeological excavation also took place in the area to examine building architecture, metal artifacts and pottery.

The strontium isotope (87Sr/86Sr) analysis revealed some interesting data. In the study, animal bones were used as proxy for the local biosphere. The animal samples demonstrated that the local Nile Delta region has a narrow 87Sr/86Sr range. A restricted range of local values is considered ideal for determining those who spent their childhood in the northeastern Nile Delta and those who grew up somewhere else and then moved to the region.

Lead author of the study, Dr. Chris Stantis, in an interview with Livescience, explained the thought behind the study’s methodology. “Strontium enters our bodies primarily through the food we eat. It readily replaces calcium, as it’s a similar atomic radius. This is the same way lead enters our skeletal system; although, while lead is dangerous, strontium is not” (Weisberger 2020). The study then compared ratios of strontium isotopes from the teeth of the human remains from Tell el-Dabca to environmental isotope signatures from other regions in Egypt along the Nile.

The authors of the study claimed the results were at odds with the conventional hypothesis that the Hyksos invaded Egypt in a single massive conquest. Instead, the results seem to show that they had slowly migrated in and taken over the Nile Delta region opportunistically when Egyptian power was decentralized and weak. One issue with that interpretation is that it sounds exactly like the same scenario (in the same region) postulated for the Fourteenth Dynasty’s takeover of the Nile Delta by “Asiatics.” While it is theoretically possible that both the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Dynasties came to power in the same region in exactly the same way, (gradual infiltration), other lines of evidence make this position unlikely.

According to the study, “Manetho described the Hyksos rulers as leading an invading force sweeping in from the northeast and conquering the northeastern Nile Delta during the Second Intermediate Period in a time when Egypt as a country was vulnerable . . .” (Weisberger 2020). However, Manetho described more than that—he also included the fascinating points that 1) the foreigners were able to take over Egypt without having to strike a blow and 2) that this event happened after “God smote” Egypt (Josephus 1970a, Book 1, section 14, 610–611 quoting from Manetho’s Aegyptiaca). As we will discuss later, this more accurately describes the Fourteenth Dynasty rather than the Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty.

The Details of the 2020 Study

Of the 75 dental records tested (mostly molars) 53% plotted as people growing up outside the Nile Delta region. Thirty were estimated to be females and 20 males (25 were undetermined). Although the study in question doesn’t detail how the sex determination was made, it is likely that they used iron and/or copper stable isotope analyses, which has been shown to be somewhat effective in differentiating males from females.

Based upon the archaeological layers that the remains were taken from, they were assigned dates associated with the Twelfth through Fifteenth (Hyksos) Dynasties. The isotope analysis showed that there were more immigrants during the pre-Hyksos (Twelfth through Fourteenth Dynasty) time periods although there were still some immigrations during the Hyksos time period of the Fifteenth Dynasty. The slight majority of women to men leads the authors of the paper to believe that this is more consistent with a gradual and peaceful migration, rather than an army-led invasion (Emery 2012). The authors thus conclude that the Hyksos gradually migrated into the region, and when the time was ripe, they seized power in the Delta region. But this appears to conflict with what we read from Scripture about the slavery of the Israelites in this time period. If Egypt’s northern and eastern borders were so porous that people groups could just migrate in virtually unnoticed, then why hadn’t the Israelites just “migrated” out when their plight became harsh (as mentioned in Exodus 1:11–22, 2:23–24, 5:7–18)? Thus at least for the Fifteenth Dynasty, this interpretation is at odds with the biblical text.

The Limitations of the 2020 Study

There are a few caveats about the study that need to be mentioned here. First, this is a small sample of only 75 individuals, so any findings must be considered tentative at best. The second is that, according to the study, “non-locals south of the northeastern Nile Delta would show the same strontium values as locals to the region of study; individuals from major centers such as Memphis, Thebes, and even further south into Upper Egypt and Nubia might be present in this assemblage but unidentifiable using strontium isotope analysis” (Stantis et al. 2020, 9). So even some of the “local” human remains in question could be from Nubians (present-day Sudan), which could make some immigrants appear as “locals.” The paper also states that “recent research suggests that fertilization with lime in modern agriculture affects interpretation of strontium isotopes although that is not expected to be a major issue in the fertile Nile Delta” (Stantis et. al. 2020, 6). However, there is one problem with that assumption. The Israelites living in the Nile Delta region were shepherds and herdsmen, something which the Egyptians considered an abomination (Genesis 46:33–34, 47:3).1 And manure from cattle and sheep and goats can contain significant amounts of calcium carbonate (lime) (Ogejo et al. 2010, Tanimu et al. 2013). So the absolute dismissal of any contamination here seems to be a little presumptuous.

However, the biggest shortcoming of the study is that it covers a span of over three centuries under conventional chronology—and the influx of a new population (or populations) could have easily been missed. We know there were large numbers of Semitic migrants coming into Egypt both during and after the Twelfth Dynasty. These immigrants settled in Egypt when there was the opportunity, and the very next generation would have been “native born” showing the same strontium levels. Some of these immigrants may have left with the Israelites but many others may have stayed behind. It is almost certain that many of those who stayed behind comprised a significant portion of the Fourteenth Dynasty. In fact, the paper’s mention of the immigration of more females than males does makes sense of what we would expect of the Fourteenth Dynasty. The males were already in the Nile Delta working as miners and skilled workers, and their wives, sisters and/or daughters migrated in afterwards. This also makes sense of Manetho’s statement. He was correct that an invading force swept in from the northeast and conquered the northeastern Nile Delta, that the foreigners were able to take over Egypt without having to strike a blow and that this event happened after “God smote” Egypt. What he was not correct about was that this was the Fifteenth Dynasty Hyksos, because either he conflated the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Dynasties or viewed them as a single “foreign invasion” (which they were not).

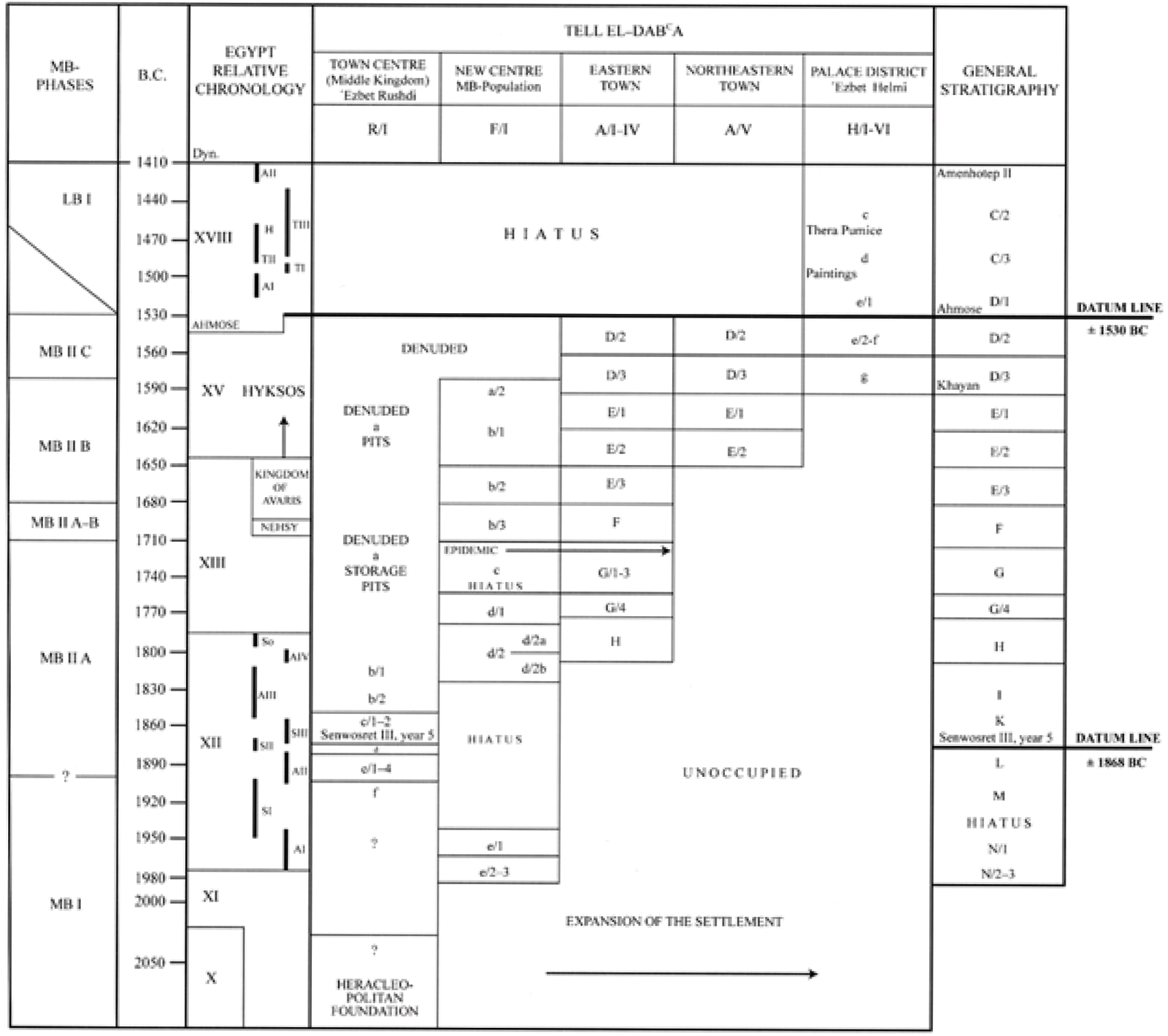

Fig. 1. The site stratigraphy system map of Tell el-Dabca. Stantis, C. et al. “Fig. 3. The site stratigraphy system,” https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0235414. CC-BY-4.0.

The Layout of Tell el-Dabca

The study also states: “All metalwork from Area A/I and A/II (see fig. 1) comes after stratum E/1-D/3 during the Hyksos time period” (Stantis et al. 2020, 3). However, these levels come from 30–60 years after the proposed Hyksos incursion, so they say nothing about the people at the site at the beginning of the Hyksos occupancy. The study says, “Area A/II is the largest cemetery of the site, as well as the largest sample in this study, and it is the most comprehensively published area of Tell el-Dabca. Occupation in Area A/II began with small scale settlement activity throughout strata H-G/1” (Stantis et al. 2020, 3). This is interpreted as Late Twelfth to Thirteenth Dynasties.

The appearance of a distinct eastern Delta material culture, interpreted as that of the Fifteenth Dynasty, was identified from stratum E/2-1 onwards, with further changes during D/2. Large temples were built in the Area during stratum F, E/3 and E/2 (interpreted as the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Dynasties) (Griffith and White 2025, fig.15). Temple III, built during stratum F and E/3 (Fourteenth Dynasty), continued in use throughout the time period. However, the “epidemic” that David Rohl connects to the tenth plague (Rohl 1995, 280–283) is at the end of stratum G (Thirteenth Dynasty) with the Hyksos not coming in until the start of E2, which the article also acknowledges witnessed the building of large temples.

Comparison of this Study to Manetho’s Account

So if the initial wave of invaders came in at the start of stratum F, this was not the Hyksos, but the Fourteenth Dynasty, 30–40 years before the first of the occupants were buried at the cemetery that provided samples for the study—plenty of time to reach a point where most of the Fourteenth Dynasty population (labeled as Nehsy/Kingdom of Avaris in the study, named after the fifth king of the Fourteenth Dynasty) at Avaris had become “Egypt-born” soon after the influx of these foreign-born invaders. This 30–40 year time period also coincides quite nicely with my estimated <35 year length for the Fourteenth Dynasty. Under this scenario, the human remains mentioned in the study do not represent one generation burying their dead and continuing on, but their extermination by the Fifteenth Dynasty Hyksos. Curiously, Manetho makes a very telling statement regarding the Hyksos invasion “Having overpowered the chiefs, they then savagely burnt the cities, razed the temples of the gods to the ground, and treated the whole native population with the utmost cruelty, massacring some, and carrying off the wives and children of others into slavery” (Manetho 1964, frag. 42, 1.75–79.2). Carefully notice the wording used: the Hyksos “killed the chiefs” (plurality of rulers which the Fourteenth Dynasty was noted for), killed many in the Nile Delta region (a non-Egyptian Fourteenth Dynasty) and carried others off into slavery.

It is likely that Manetho had earlier conflated the Hyksos with the Fourteenth Dynasty, but here his statements seem to be accurately describing the Fifteenth Dynasty Hyksos. Historians often dismiss Manetho here, but from an outside standpoint this invasion would have been one group of Asiatics killing off another such group (although it is also possible that there were some local Egyptian serfs in the delta region). At this initial point, even the Egyptian Thirteenth Dynasty would have barely noticed, why should they care if non-Egyptians killed other non-Egyptians? In fact, they may have even thought that this would make taking back the Nile Delta easier to accomplish. Of course, that attitude would change quickly once the Hyksos started marching south.

Additionally, that point only marks the beginning of the Area A/IIS cemetery and many of the remains tested may have come in the decades following that point. Testing the remains of individuals who came even one generation after the potential Hyksos invasion would show a Nile delta signature. So, this study tells us little about the makeup of the proposed gradual infiltrators (Fourteenth Dynasty) nor the potential invaders (Fifteenth Dynasty).

To establish the paper’s conclusion that the Hyksos rise to power was not the result of invasion, it would need to be determined that this was a Hyksos cemetery (vs. a burial ground of locals that had carried over from the population prior to the Exodus) or of the Fourteenth Dynasty, which controlled the area before the Hyksos, and that the remains tested were from the first generation of arrivals before many of the next generation started dying. However, neither of these factors are evident. These oversights lead to an unsupported conclusion that runs counter to the invasion model that is supported by Manetho, the Ipuwer Papyrus, and other Egyptian documents from that era.

The Late Twelfth and the Thirteenth Dynasties: Egypt in Turmoil

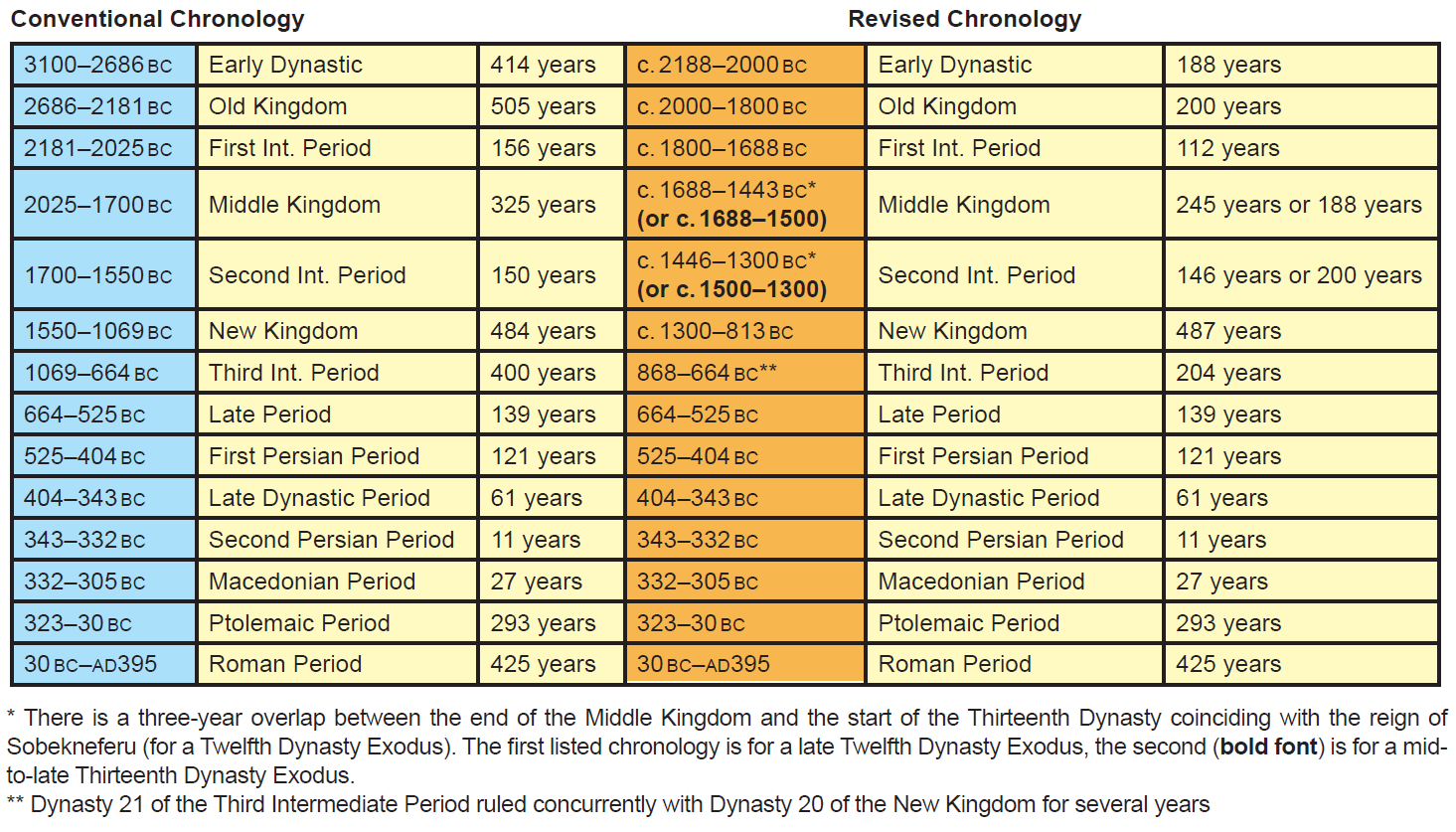

The Hyksos are conventionally dated as ruling parts of Egypt, mostly Lower (Northern) Egypt from 1650–1530 BC. However, in a Revised Egyptian Chronology2 (hereafter REC), those dates come down approximately 200 years and reflect an early post-Exodus time period. Conservative biblical archaeologists and Egyptologists place the Exodus at either 1491 BC or 1446 BC (whereas liberal biblical scholars usually place the Exodus at 1250–1220 BC, although some may propose an even later date). Many Christian scholars and others who hold to a late Exodus date, and who give some credit to an extended wandering period after the Exodus before entering Canaan, put it decades earlier because of the Merneptah Stele indicating Israel was in the land of Canaan no later than 1208 BC by standard dating yet they still retain traditional Egyptian chronology dates).3 Using a REC and the 1446 BC Exodus date, we have a possible Twelfth Dynasty, a middle and two late Thirteenth candidates for the Pharaoh of the Exodus, either Amenemhet IV, Neferhotep I, Khaneferre Sobekhotep IV, or Merneferre Ay. The former is considered the last male Pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty (it appears his sister Sobekneferu, also called Neferusobek, ascended the throne for a few years after his death); Neferhotep I had at least two sons, but named his younger brother as coregent, Sobekhotep IV and Merneferre Ay are Pharaohs of the late Thirteenth Dynasty, which is one of the most fragmented, poorly attested periods in Egyptian history.

Most late Twelfth and almost all Thirteenth Dynasty Pharaohs had short reigns, and many of those listed are completely unknown save for odd fragmentary inscriptions or mentions of coregencies and there are very few monuments dating from the period. Both Amenemhet IV (also spelled Amenemhat) and Neferhotep I’s royal mummies have never been found, do not appear to have been firstborn sons themselves, nor did their son succeed them on the throne,4 making them viable candidates for the Pharaoh of the Exodus. In the case of Sobekhotep IV, it is believed that he is buried in the Abydos-south S10 tomb, but his eldest son Amenhotep died before he did, and Merneferre Ay is the last Pharaoh of the Thirteenth Dynasty known to have objects found in Lower and Upper Egypt which indicates that Egypt was still united during his reign. His eldest son Aya appears to have predeceased him and a younger son named Merhotepre Ini II took over the throne but appears to have only ruled in Thebes. Egyptologist Chris Bennett estimates that the lower range of about 20–40 years at most may separate Year 1 of the Thirteenth Dynasty king Merhotepre Ini from Year 1 of the Theban king Nebiriau I of Dynasty 16 (Bennett 2002, 235, 239). And Porter states that perhaps the entire SIP (Second Intermediate Period) was only about 40 years (Porter 2022, 4).

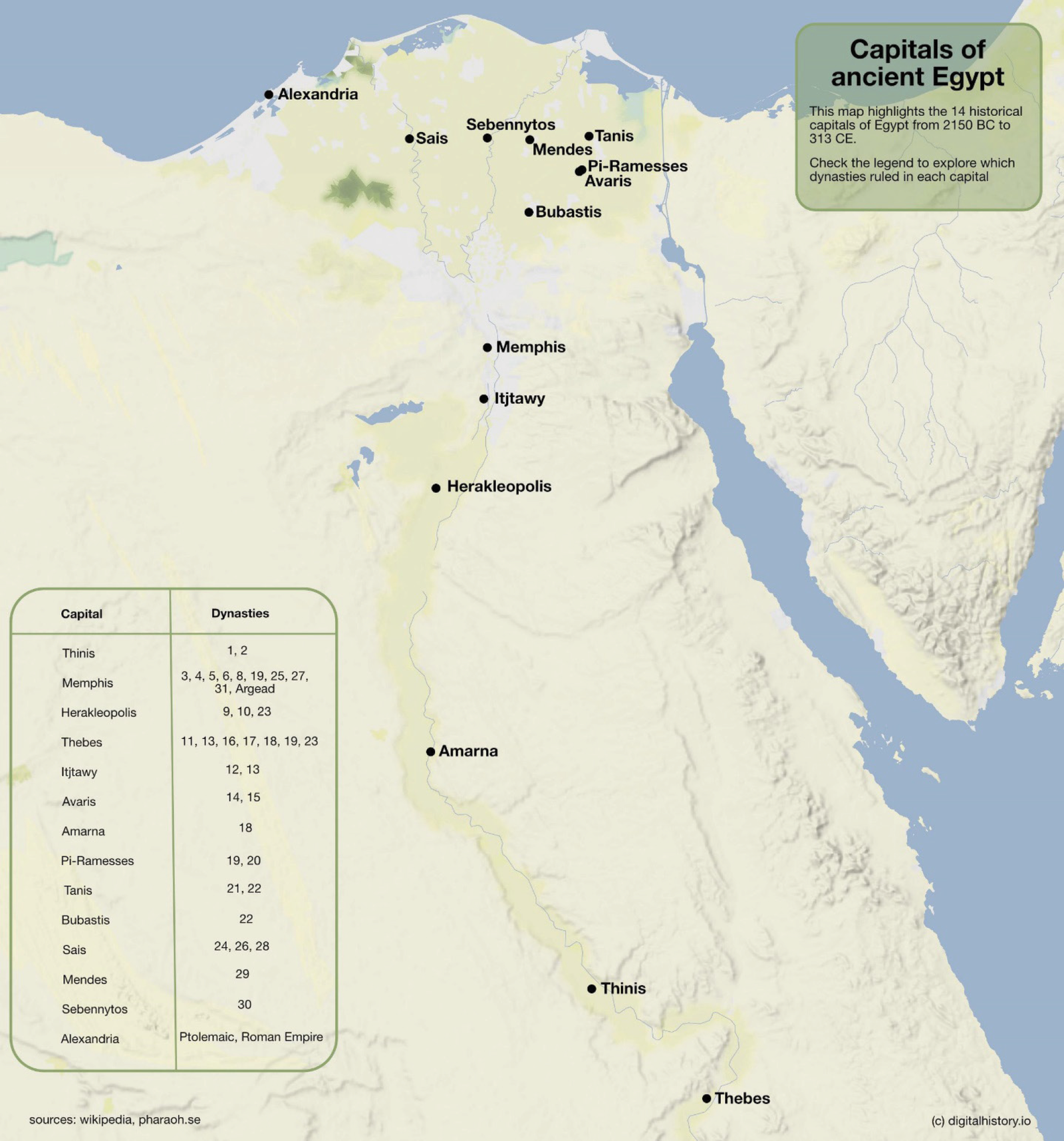

During the Twelfth Dynasty, the capital of Egypt was moved from Thebes (central Egypt) to Itjtawy (north central Egypt although the exact location is still unknown) and remained there during most of the Thirteenth Dynasty (moving back to Thebes towards the end of the Thirteenth Dynasty). Due to the fragmented nature of (at least the late) Thirteenth Dynasty’s records, it is difficult to piece together a coherent chronology of events (and ruling Pharaohs), but even secular archaeologists recognize that Egypt was in turmoil at this time. The Fourteenth Dynasty appears to have arisen and ruled concurrently with the Thirteenth Dynasty, with the Fourteenth Dynasty’s power base being situated in the Nile Delta region, with the city of Avaris as their likely capital. Avaris is often considered the same as the biblical city of Rameses, one which the Israelites built and likely where some lived (Exodus 1:11, Exodus 12:37, Numbers 33:3).5 See the list of Ancient Egyptian capitals in fig. 2.

Even at the end of the Twelfth Dynasty, secular Egyptian historical records are contradictory, with Amenemhet IV being dated by various Egyptologists as starting his reign (according to conventional chronology) in 1822 BC to as late as 1772 BC. Neferhotep I is no less contentious with various Egyptologists listing his 11 year reign (according to conventional chronology) anywhere from 1747–1736 BC down to 1721–1710 BC. During this period (late Twelfth through Fourteenth Dynasty) we have numerous short-reigning Pharaohs, including the first documented female Pharaoh, several Pharaohs who appear to not be direct descendants of the previous one, and two ruling Pharaohs from different locations in Egypt (Itjtawy, then Thebes and Avaris).

A Quick Background on Dynasties 13–17

According to secular Egyptologists, the Fourteenth Dynasty was not the Hyksos (Fifteenth Dynasty), but a local population living in the Nile Delta that revolted from under the Thirteenth Dynasty’s rule from Itjtawy (several hundred miles further southwest) and so ruled Egypt concurrently alongside the Thirteenth Dynasty. It may be this revolt (or an uprising further south from the Nubians) that prompted a move back to Thebes for the latter part of the Thirteenth Dynasty. Conventional Egyptian chronology places this Fourteenth Dynasty from either 1805–1650 BC (Ryholt 1997) or 1725–1650 BC (Ben Tor, Allen, and Allen 1999), with anywhere from 56 to 76 ruling Pharaohs (doing the math that’s a new Pharaoh every two years on average). But using a REC and placing the Exodus at the end of the Twelfth Dynasty or preferably sometime (mid to late) in the Thirteenth Dynasty makes much more sense of the new study and sheds light on this turbulent time in Egyptian history.

To put this in perspective, Dynasty 13 (Lower Egypt) ruled concurrently with Dynasty 14 (Middle to Upper Egypt) for a few decades. Then Dynasty 14 was overthrown by Dynasty 15, who also ruled concurrently with Dynasty 13, before taking over Middle Egypt and weakening 13 to the point of collapse. Dynasty 16 (Upper Egypt) then took over from Dynasty 13 but only in Upper Egypt (with Thebes as their capital). Dynasty 17 followed 16 and began to make inroads into weakening Dynasty 15, which was eventually driven out by the first Pharaoh of the New Kingdom Dynasty 18.

Can Scripture Provide Any Further Clues in Genesis and the Early Chapters of Exodus?

The term Hyksos never appears in Scripture so we cannot point to a specific people group so named. But from the account of the Exodus and subsequent passages, we can make a reasoned hypothesis. Although there is much written in Scripture about the slavery of the Israelites in Egypt, there are also a few sprinkled passages about other people besides the Israelites who were also enslaved. Just prior to the Exodus, during the seventh plague (hail) that God sent upon Egypt, we read that “whoever feared the word of the LORD among the servants of Pharaoh hurried his slaves and his livestock into the houses” (Exodus 9:20). These “servants” could have been Egyptian, or they could have been foreign vassals. When Joseph was vizier in Egypt and the famine was severe in the land, all of the Egyptian landowners ended up selling their land and themselves into the servitude of Pharaoh (Genesis 47:19–25). But Genesis 47:14–15 also mentions that people from the land of Canaan had exhausted their money for buying grain during the famine. Could it also be that they, like the Egyptians also sold their livestock and then themselves and their land in order to have food on the table? The text here is not explicit, except regarding parcels of land (and this was expressly Egyptian family property) so this can only be a tentative proposal, but it seems feasible that this was the case. Because if Canaan wasn’t in sight here, why does the text of verse 15 mention it? If Canaan is in view here (along with Egypt), what nations within Canaan would have been the most affected?

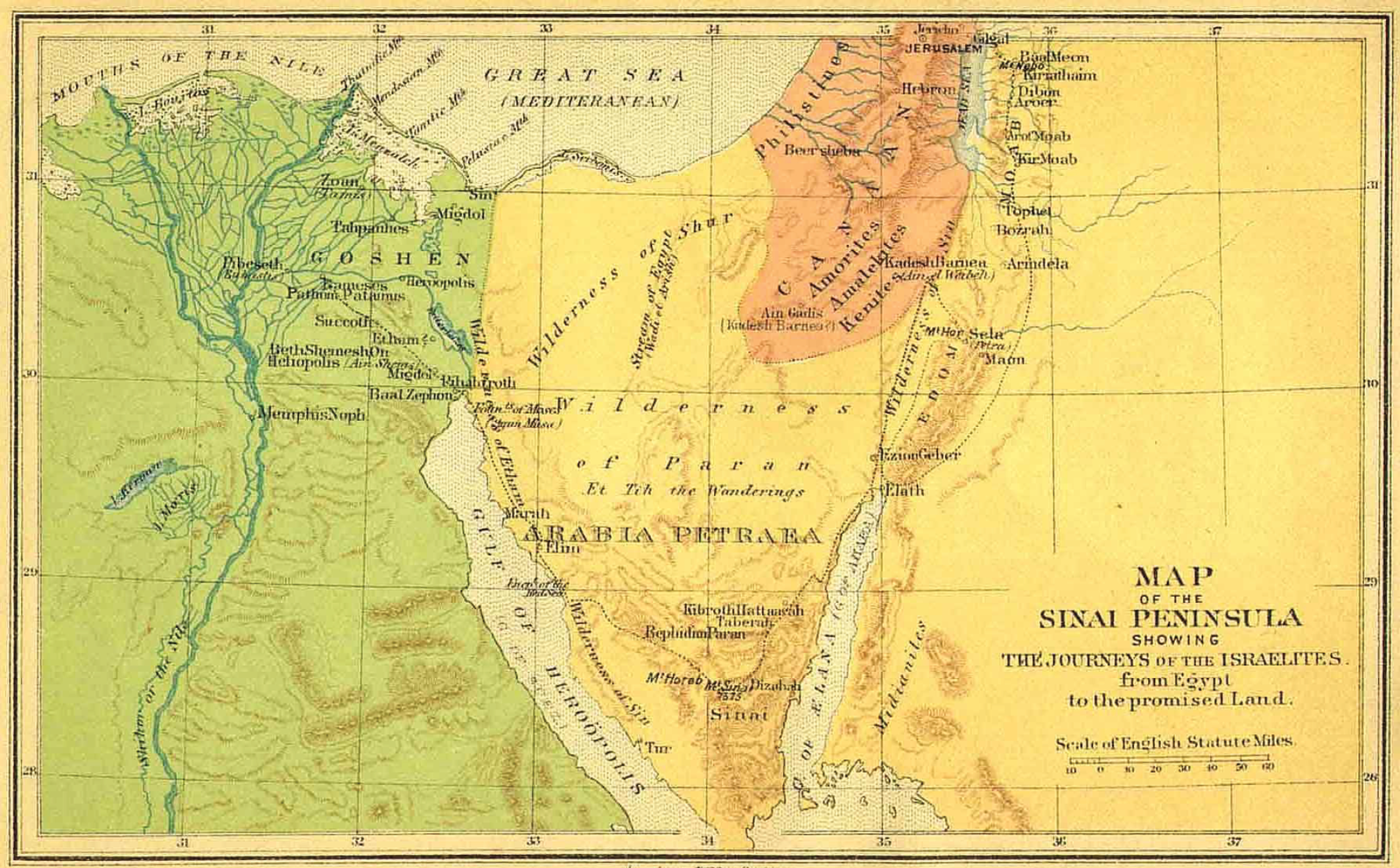

Looking over the maps below6 and the areas closest to Egypt, without year-round water sources (like the Jordan in northern and central Israel), a number of biblical names jump out as the most likely candidates to have been most affected by the famine: the Amorites, Amalekites, Philistines, Kenites, and Edomites. Prior to coming to Egypt, Jacob lived in Hebron and then Beersheba, both in southern Israel, which was also drastically affected by the severe famine.

Fig. 2. List of ancient Egyptian capitals and which corresponding dynasty they belonged to.

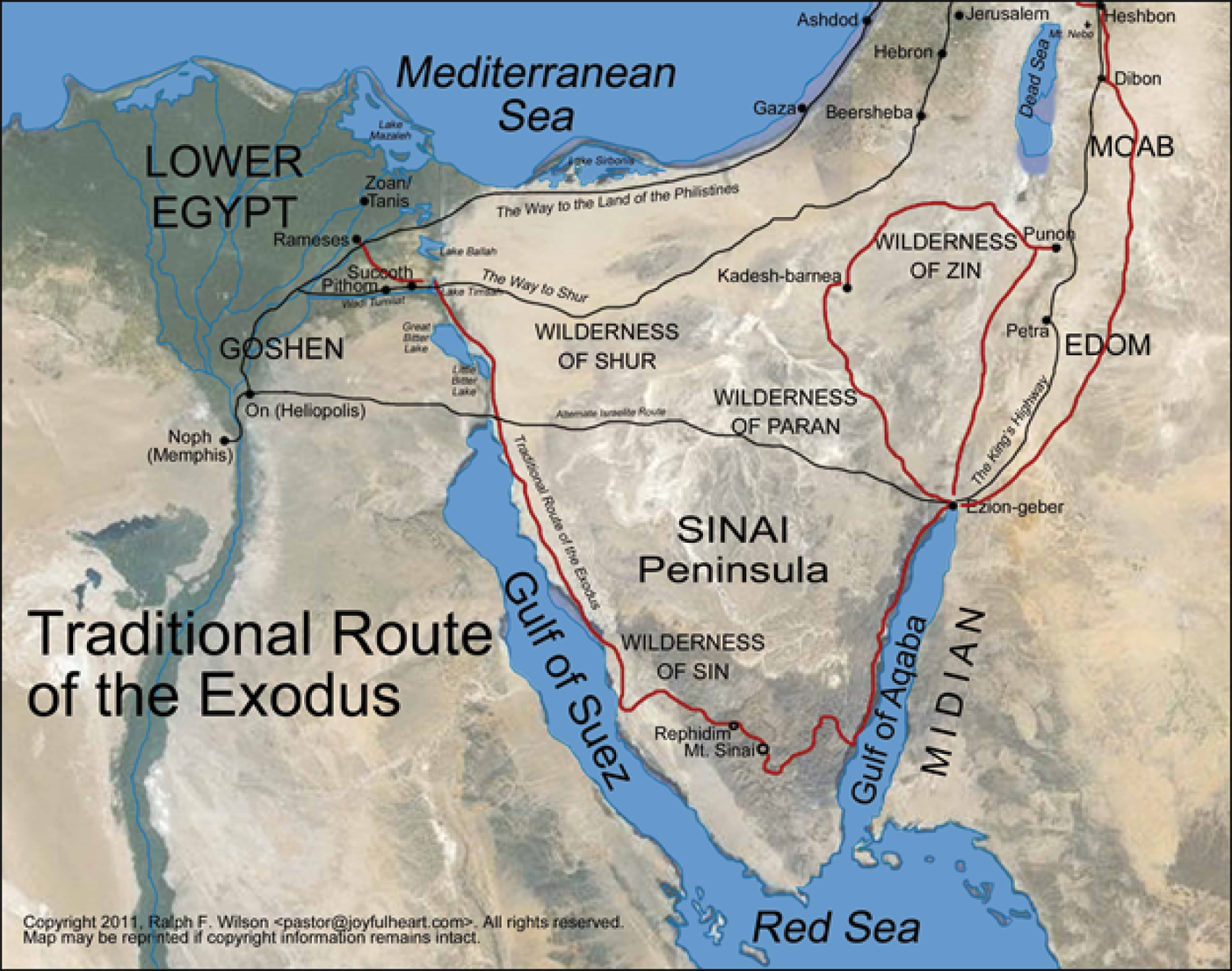

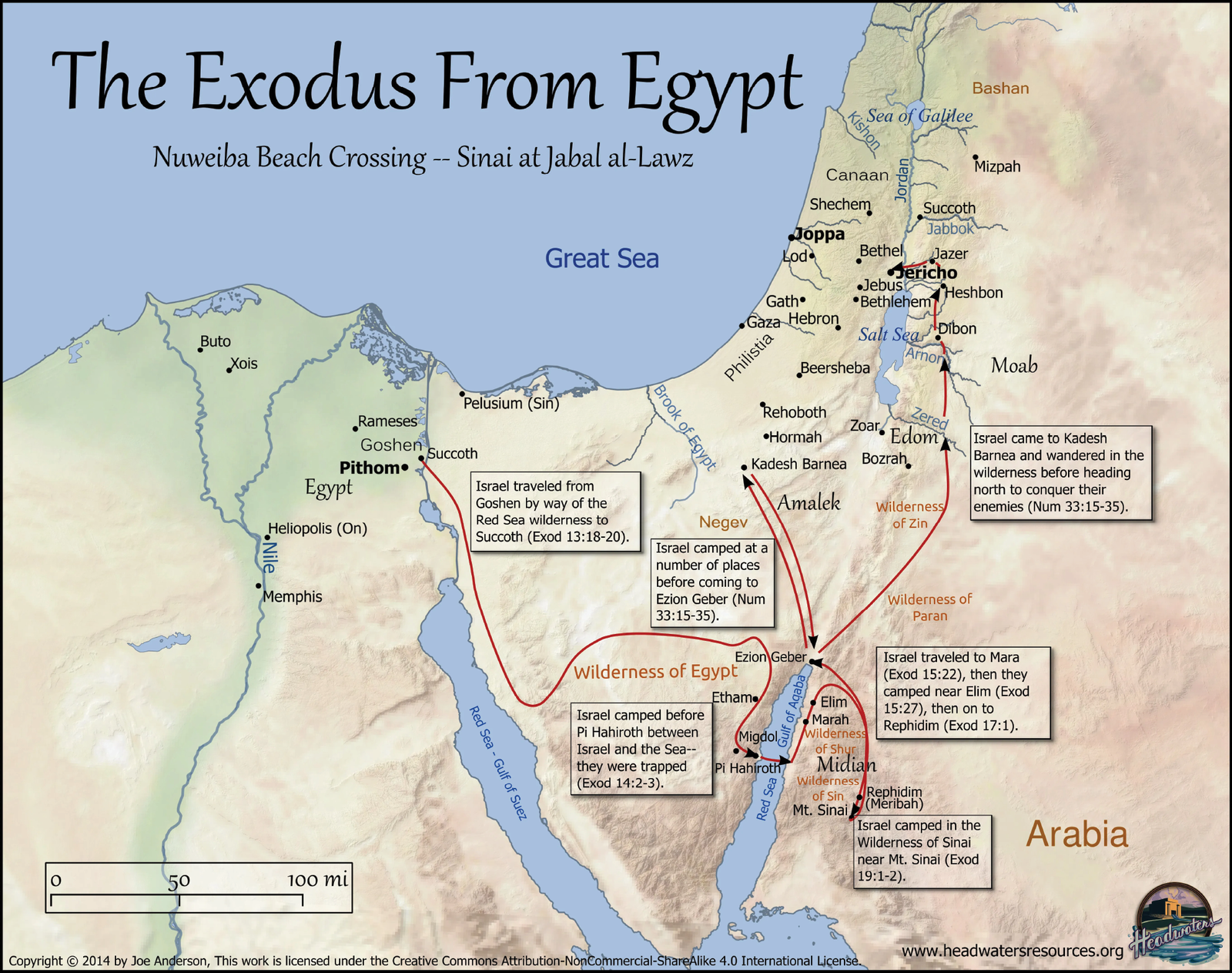

Fig. 3. Map showing neighbouring peoples. Bible maps from the American Bible Society, 1888. Map of the Sinai Peninsula Showing the Journeys of the Israelites from Egypt to the Promised Land. https://www.godweb.org/maps/109.htm. Public Domain.

Fig. 4. Moses Bible study map showing traditional Red Sea crossing. Ralph F. Wilson, pastor@joyfulheart.com. All rights reserved. https://www.jesuswalk.com/moses/maps/map-egypt-sinai-exodus-route-topo-3000x2363x300.jpg.

Fig. 5. Map showing Gulf of Aqaba crossing. Joe Anderson, “Exodus route map,” https://headwatersresources.org/exodus-route-map/. CC-BY-4.0.

If any of the Canaanite nations were postulated to have sold their livestock and themselves to Egypt in exchange for grain, the foremost among them (ranked in order) would be the Amalekites, Amorites, and Kenites. Edom was outside Canaan (so per Genesis 47:14–15 is likely excluded), and the Philistines were seagoing peoples and so would have likely just doubled down on fishing to stave off starvation, and also possibly picked up potable water on Mediterranean islands. The majority of the Kenites lived in mountainous regions (Numbers 24:21) and Moses’ father-in-law Reuel/Jethro was of Kenite as well as Midianite origin (Numbers 10:29, Judges 4:11) and had shown kindness to Israel when they came out of Egypt (1 Samuel 15:6), so we should probably exclude them. Amalek would be ranked first since they were the closest in proximity to Egypt (see fig. 3) and also Numbers 13:29, which mentions them dwelling in the Negeb (the Negev of present-day southern Israel) and also in much of the northern Sinai Peninsula as Josephus records.

Who Were the Amalekites?

Although it is often assumed that the Amalekites were descendants of Amalek, a grandson of Esau (Genesis 36:12), there are numerous passages that point to another possible option. Some Bible verses seem to indicate that there was another nation known by the same name, which was a power in the region of Canaan long before the grandson of Esau came on the scene and continued to be a power during Israel’s history. In fact, every passage that has indicators of the identity of the Amalekites can be seen as supporting the idea that this group was the original Amalekites and not one of the clans of Esau.

- They are mentioned in Genesis about 135 years before Esau’s grandson Amalek was born, and perhaps three centuries before his descendants could be expected to be a strong force. The four kings who captured Lot are said to have defeated the country of the Amalekites before Abraham’s tenth year in the land—or before Abraham was 85 years old (Genesis 14:7). Recall that Abraham was 100 when Isaac was born (Genesis 21:5), and Isaac was 60 years old when Jacob and Esau were born (25:26).

- The Amalek who was Esau’s grandson, would become one of the 14 chiefs of the Edomites (Genesis 36:15–19). However, Balaam says of Amalek that he was the first among nations (Numbers 24:20). This would be an odd designation for a people that was only one of 14 clans among Esau and who had only been around about as long as the Israelites had been, but consistent with the Amalekites being a powerful nation in the land at the time of Abraham.

- Edom and Amalek are mentioned separately in several passages of Scripture. In 1 Chronicles 18:11, King David dedicated to the LORD, together with the silver and gold that he had carried off from all the nations, from Edom, Moab, the Ammonites, the Philistines, and Amalek. The same is stated in 2 Samuel 8:11–12. Edom and Amalek are also distinguished from one another in Numbers 24:18 and 20.

- God gives opposite commands concerning the Amalekites who attacked Israel, and the people of Esau (which included the tribe of Esau’s grandson Amalek).

After the Israelites defeated the Amalekites on their way to Mount Sinai, the LORD said to Moses, “I will utterly blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven” (Exodus 17:14). And 40 years later Moses wrote, “. . . you shall blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven; you shall not forget” (Deuteronomy 25:19).

Yet when Israel was coming up from Mount Sinai and came to Edom (which had Esau’s grandson Amalek as one of its tribes) God said not to contend with the people of Esau (Deuteronomy 2:2–5). This does not sound like the Amalekites who had not been afraid to attack Israel on their way to Mount Sinai and whom God had cursed. - Amalek the grandson of Esau was one of the clans of Esau who lived “east” of the Promised Land in Seir, a land that God promised to Esau and his descendants. However, the Amalekites who featured so prominently in Israel’s history seemed to inhabit a much wider region including the east, but also the Negev of Israel, which was west of Seir and inside the land God had promised to Israel. Additionally, the Amalekites also occupied and controlled parts of Syria and Lebanon.

- The Bible makes it clear that the Negev was in Canaan and part of the Promised Land (Genesis 12:9, 13:1, 24:62; Numbers 13:17–18, 33:40; Deuteronomy 1:7, 34:1–4; Joshua 10:40, 11:15–17, 19:8; Judges 1:9). The prophet Obadiah mentions that in later times Edom’s homeland of Mt. Seir would be conquered by people of the Negev (Obadiah 1:3, 19), therefore Edom was not in the Negev.

- The Edomites feared Israel as they came up out of Egypt. In contrast, the Amalekites did not fear Israel but attacked them more than once and were cursed to extinction by God who wanted them blotted out (rather than being promised the land they lived in, as the tribes of Esau were). The Amalekites who are described as being hostile to Israel and the chiefdom tribes descended from Amalek the grandson of Esau appear to be two different peoples.7

However there are other biblical scholars and historians who believe the mention of the Amalekites in Genesis 14:7 is anachronistic and is mentioning the lands that would be later occupied by Amalek.8 They therefore believe that Amalek as mentioned in later Scripture is a people which sprung from Esau’s grandson. They also take Balaam’s statement about Amalek being the “first among nations” (Numbers 24:20) as referring to them being the first to attack Israel after the Exodus.9 And the Amalekites often united with other Semitic groups in alliances (often against Israel) which could strongly imply that they were also Semitic (see “Were the Amalekites Semitic Peoples?” section below).

It is possible that the Amalekites as well as the Amorites sold their livestock and possibly themselves to Egypt during the famine of Joseph’s time. Others, especially skilled craftsmen might have moved to Egypt to ply their trades or work in mines, masons/carpenters might have moved to Egypt to help with Pharaoh’s building projects, etc. Undoubtedly some of the people from these nations migrated into the Nile Delta region (legally and possibly illegally) while others stayed in their homeland. In fact, it seems likely that during the earlier part of the Twelfth Dynasty, the Amalekites had been at war with the Egyptians and if Pharaonic propaganda is not overstating the fact, the Amalekites had decisively lost. So the study, which argues for the gradual migration/infiltration model, would certainly be the case for the late Twelfth Dynasty and early Thirteenth Dynasty time periods. The famine of Joseph’s time made Egypt very appealing to all of Canaan which was languishing (Genesis 47:13). This would have brought an influx of migrants, as well as herdsmen, tradesmen, and craftsmen from Canaan into Egypt. However, this model would not totally fit the Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty, which is what the Stantis et al. research paper argues for.

Can Egyptian Hieroglyphic Writings and Tomb Paintings Yield Any Clues on Who the Fourteenth (Amorite) and Fifteenth Dynasties (Hyksos) Were?

Before jumping into Egyptian records of their dealings with “Asiatics,” their generic name for all foreigners (Butner 2007, 22–23) coming from the north and east, it is important to note what the Pharaoh who “did not know Joseph” said about the current political climate: “Come, let us deal shrewdly with them, lest they multiply, and, if war breaks out, they join our enemies and fight against us and escape from the land” (Exodus 1:10). The Pharaoh acknowledged that there were enemies of Egypt, and they were close enough that the Israelites might be tempted to join with them.

That is important to consider when looking over Egyptian texts from the late Tenth through to the late Thirteenth Dynasty. The first text to consider is The Instruction Addressed to King Merikare (late Tenth Dynasty Pharaoh).

But this should be said to the Bowman:

Lo, the miserable Asiatic,

He is wretched because of the place he’s in:

Short of water, bare of wood,

Its paths are many and painful because of mountains.

He does not dwell in one place,

Food propels his legs,

He fights since the time of Horus,

Not conquering nor being conquered,

He does not announce the day of combat,

Like a thief who darts about a group.

But as I live and shall be what I am,

When the Bowmen were a sealed wall,

I breached [⸢their strongholds⸣],

I made Lower Egypt attack them,

I captured their inhabitants,

I seized their cattle,

Until the Asiatics abhorred Egypt.

Do not concern yourself with him,

The Asiatic is a crocodile on its shore,

It snatches from a lonely road,

It cannot seize from a populous town (Lichtheim 1973, 103–104)

This description accurately depicts both the Amorites and Amalekites of the later Fourteenth and Fifteenth Dynasties. The Amorites lived in the mountains (Numbers 13:29; Deuteronomy 1:7, 19–20, 44; Joshua 10:6; Judges 1:35–36) and the Amalekites lived primarily in the desert (“short of water, bare of wood”) as per Numbers 13:29 and 14:25. Both groups were opportunists and in Scripture are characterized as attacking Israel (or other people groups, or even each other) when there was a moment of weakness or the nation of Israel was being punished for lapsing into idolatry.

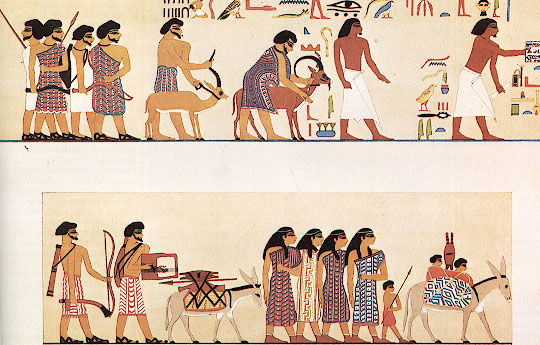

At the tomb of Khnumhotep II (an Egyptian noble who served two successive Pharaohs) at Beni Hassan dating from the reign of Pharaoh Senusret II (fourth Pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty) are several painted panels, one of which has a group of Asiatics depicted as bringing funerary tribute to Khnumhotep II. Khnumhotep II’s principal titles were Administrator of the Eastern Desert and Mayor in Menat Khufu, which is believed by some scholars to mean the desert fringes on the eastern side of the Nile Valley, stretching all the way to the Red Sea (Kamrin 2009, 22). The Asiatics in question, termed “Aamu of Shu” are then likely from the Eastern Desert, which encompasses the Sinai Peninsula and the Negev, making them likely either Amorites or Amalekites. Both inscriptions in the tomb label the members of the group “Aamu.” This term is usually translated by Egyptologists as “Asiatic” and is considered to be a Semitic loanword (Kamrin 2009, 22).

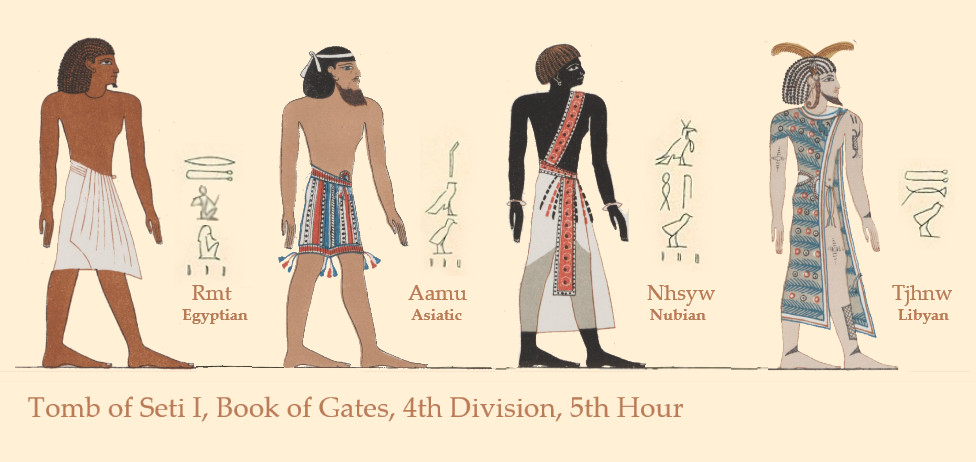

One of the often-noted characteristics of Asiatics in Egyptian art is their yellow-painted skin. Although this is recognized as a stylized technique for depicting foreigners, and not necessarily an indication that they considered their skin to be that color, it does indicate that they saw a defining characteristic associated with skin color that was meaningful to them and was a boundary marker between them and Other(s). This is made evident in the regular depiction of other groups in contrasting hues. In the famous painting of “Horus and the Four Races” from the tomb of Seti I, these standard colorations appear: Egyptians are red-brown, Nubians are black, Asiatics (Aamu) are yellow, and the Libyans are a lighter peach? (Pruitt, 2019, 113).

Fig. 6.Book of Gates—Tomb of Seti I. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Book_of_Gates,_4th_Division,_5th_Hour,_Tomb_of_Seti_I_with_Eng.png. CC BY 4.0.

Of interest to note is that the name “Amu” is specifically given to the Hyksos (as well as the more generic “Retjenu” which could include all Asiatics). Although Aamu and Amu are related linguistically, it appears that the terms describe two distinct groups of Asiatics, with the Aamu likely being Amorites.

What is clear, however, is that Asiatics, many of whom embraced traditional Amorite customs, inhabited Avaris by the late Middle Kingdom based on the chronological evidence now available. Furthermore, although not all Asiatics at Avaris need have participated in long-distance trade, there is little doubt that many did, while others engaged in a variety of local crafts brought with craftsmen from their homelands, whether for the production of ceramics, tools or weapons, and likely even elements of dress and adornment. The evidence for these crafts reveals the maintenance of important elements of Asiatic identity that, along with the burial customs attested, affiliate this population with Levantine populations who, in the absence of additional data, should be identified as Amorite. (Burke 2018)

Fig. 7. Procession panel of Khnumhotep II. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ibscha.jpg. CC BY-SA 3.0.

However, it should be noted that the Asiatics in this “procession” panel of Khnumhotep II seem to not be captives, but merely vassals paying tribute, foreign workers showing off their mining skills and wares or even foreign dignitaries paying last respects (Mourad 2014, 142–148). It may well be that prior to and up until that time (the reign of Senusret II) some peoples from the Eastern Desert, the Negev and central-to-southern Israel (Canaanite at the time) who were skilled workers (miners, builders, craftsmen) migrated into Egypt voluntarily and became working class “Asiatics” who lived in and around the Delta region. This then makes the identification of the Aamu of Shu as (most likely) Amorites, who came to Egypt as skilled laborers and possibly merchant traders. In accord with the study mentioned previously, the reason we see an influx of these “Asiatics” mostly from the Twelfth to the Fourteenth Dynasty, is that they were Amorites who worked and traded in Egypt, then immediately after the Exodus and the subsequent chaos in the region, they wrested power from the remaining weak infrastructure, took over the Nile Delta and ruled as the Fourteenth Dynasty. They were subsequently eradicated or driven out by the Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty.

Yet just one Pharaoh after the one depicted in the procession panel, during the reign of Senusret III (Twelfth Dynasty) we read the following from the stela of Sebek-khu (one of the Pharaoh’s soldiers): “His Majesty went downstream to overthrow the Bedouins of Asia. His Majesty arrived at the district named Sekmem. His Majesty was making a good start to return to the palace, (when) the Sekmem and the wretched Retjenu fell (upon him?) (while) I was serving at the rear of the army. Then the soldiers of the army went to fight with the Asiatics. I struck an Asiatic, and I had his weapons taken by two soldiers of the army without ceasing fighting; I was brave, I did not turn my back to the Asiatic. As Senwosret lives for me, I have spoken the truth!” (Price 2014).

The term Retjenu was an ancient Egyptian name for parts of the northern Negev, Canaan, and Syria. It covered the region from the area around the border of Canaan north to the Orontes River in Lebanon and Syria. Almost certainly the Amalekites were a major part of this confederation. Most scholars here think the place name Sekmem is the same as biblical Shechem in central Israel. Recalling that Jacob’s family would have either still been in Hebron, newly arrived in Egypt at this time, or else enslaved within Egypt (depending on what Dynasty—the Twelfth or Thirteenth) the Exodus is postulated to have occurred under, the people of Shechem at that time were Canaanites (Genesis 12:6). Shechem was later part of the tribal territory of Manasseh (Joshua 17:7) but was also both a city of refuge (Joshua 20:7) and a Levite city, set aside for the Kohathites (21:20–21).

Interestingly, there is no evidence either from Scripture or archaeology that the Israelites conquered Shechem by force (during the conquest of Joshua’s time) which lends credence to the Egyptian account that Senusret III destroyed the inhabitants, and 50 to 100 years later, the Israelites were able to just take over the city and surrounding area without a fight. It may also be that at this time some of the Asiatics within Egypt were either made into foreign vassal serfs or even actively enslaved, as distrust for Asiatics intensified due to border skirmishes and active revolt needed to be stamped out with military campaigns.

Could Some Amalekites Have Left Egypt During the Exodus?

Does the Bible shed any light on this? It just might! At the time of the Exodus, we read that not only Israelites, but a “mixed multitude” left Egypt along with them (Exodus 12:38). Some of these peoples must have genuinely aligned themselves with the Israelites, becoming proselytes to the God of Israel, as we see later references to “strangers” and “sojourners” as early as Sinai (Exodus 22:21). And when God commanded Israel to establish six cities of refuge once they reached the Promised Land, they were to be for both Israelites and any foreigners living among them who had accidentally killed a person (Numbers 35:10–15).

Some of this mixed multitude may have been Canaanites and almost certainly some were Amorites and Kenites. Some may have even been Egyptian, perhaps those out of favor with the ruling Pharaoh, or Egyptians who were tired of being vassals to the ruler and having no land ownership. We read in Leviticus 24:10 that there was an Israelite woman who had a son by an Egyptian father, likely testifying to some Egyptians leaving Egypt with the Israelites. And if the wife of Moses mentioned in Numbers 12:1 was not Zipporah (perhaps due to her death), which seems likely since Zipporah was a Midianite, then it would mean that some Ethiopians were in the mixed multitude that left Egypt during the Exodus.

However, some of the people who left Egypt with the Israelites probably left for less noble reasons, basically a free “get out of servitude” opportunity, and there may have been those who viewed this as a political opportunity. We know that some of these “mixed multitude” caused dissension within the camp by encouraging the Israelites to complain about their diet of manna (Numbers 11:4). And since the Amalekites were one of the closest people groups to Egypt, it seems very likely that if the Exodus took place during the end of the Twelfth or early to mid-Thirteenth Dynasty, some would have chosen to leave during the Exodus to return to their homeland, and perhaps as spies against Israel.

The Amalekites as Candidates for the Hyksos?

Seemingly out of nowhere we read in Exodus 17:8 that Amalek attacked Israel. This happened in the second month after the Israelites crossed the Red Sea, when they were camping at Rephidim. This was even before they arrived at Mount Sinai. Living in a world of instant communication as we do now, it is sometimes hard to think of a slow spread of news. But if you put yourselves into the 1400s BC, you might be tempted to ask how the Amalekites knew where the Israelites were. While true that conservative biblical scholars estimate there were close to 2 million Israelites, they deliberately avoided going by way of the coastal route which would have brought them though Amalekite territory and then into Philistia. While it is possible that some Amalekites lived in the southeastern Sinai Peninsula, they are not listed as doing so in Scripture. In fact, God stated that he did not take them through the northern Sinai Peninsula route so they wouldn’t see war and flee back to Egypt (Exodus 13:17). Of course, the Israelites were almost certainly not equipped with many weapons when they left Egypt, but after the Egyptian army drowned in the Red Sea, it is likely that the Israelites scavenged some weapons from the dead bodies washed up on shore (Exodus 14:30).10 So the up to two-month delay between the exodus and the battle at Rephidim, had enabled the Israelites to be better able to protect themselves (humanly speaking).

If some of the mixed multitude who came out of Egypt with the Israelites were Amalekites a few could have easily slipped away from the crowd when the Israelites turned south, away from the Amalekite territories (Exodus 13:17–18). But perhaps a few stuck around to serve as spies, and so were present at the Red Sea miracle, and afterwards scurried to the Amalekite towns and notified them of the events that had happened at the Red Sea. And had they slipped away immediately after crossing the Red Sea, they would have been unaware of the Israelites arming themselves with Egyptian weapons. Picture this plausible scenario, if you’re an Amalekite enslaved (or at best serving as a vassal serf) in Egypt, and you see the country rocked by plagues and an opportunity to leave comes up, why wouldn’t you take it? Then as things pan out, a large part of the Egyptian army is completely wiped out11 and you are within a day or two’s march of your homeland. Not only would you tell your people about Egypt being ripe for the taking (and maybe freeing more of your countrymen in servitude there) but you would also tell them that there’s this ragtag group of unarmed people loaded down with riches they plundered from the Egyptians (Exodus 12:36).

Several other historians have postulated that the Amalekites were the Hyksos people. Ashton and Down did so in their book Unwrapping the Pharaohs. In chapter 13 of that book, they also mention that Immanuel Velikovsky (1952 in Ages of Chaos) and Donovan Courville (1971 The Exodus Problem and its Ramifications) had previously made the same hypothesis. Going back to 1951, we see journals citing evidences of Semitic (and possibly Canaanite) names for the Hyksos rulers (Säve-Söderbergh 1951, 58). One name which appears frequently is Hur, who appears to have been an early Hyksos chancellor (Säve-Söderbergh 1951, 58). Ironically the name Hur, in addition to being an Israelite name, is also mentioned of one of the five kings of Midian (Numbers 31:8) and Midian was also occasionally aligned with Amalek in their battles against Israel (Judges 6:3, 6:33, 7:12).

Were the Amalekites Semitic Peoples?

Velikovsky found numerous Islamic sources from between the ninth and fourteenth centuries who cited more ancient traditions and authors, saying that the Amalekites were one of the most ancient Arab tribes who dominated much of Arabia. This would not necessarily contradict the biblical account as many scholars have proposed that the Amalekites were Semitic peoples, likely originally from Syria. Recall that Jacob had fled from his brother Esau to his uncle Laban in Paddan-Aram which is likely to be equated with Harran-el-`Awamid, an ancient site ten miles to the East of Damascus in Syria. Scripture repeatedly calls Laban an Aramean (or Syrian, depending on which English translation is used) in Genesis 25:20, 28:5, 31:20, 31:24 and even assigns Jacob that title in Deuteronomy 26:5. Aram was the fifth son of Shem (Genesis 10:22). Josephus mentions that “Aram had the Aramites; which the Greeks call Syrians” (Josephus 1970b, chapter 6.3, 31). If this identification is accurate, it makes sense of the fact that the Amalekites usually teamed up with other Semitic tribes to attack Canaanites or some of those Semitic tribes which had a grudge against the nation of Israel (like the Edomites, Midianites, Ammonites, etc.).

If the above identification is correct then Midian and Amalek were Semitic peoples, through Abraham’s son Midian and Shem’s son Aram, respectively (or if the Amalekites were descended from Esau). In fact, whenever the Midianites are mentioned in association with another nation, it is always a Semitic one (Moab, Amalek, and Ishmael, for example, Genesis 37:27–28). Amalek also aligned itself with the Moabites and Ammonites (Semitic peoples) in Judges 3:12–14.

The Midianites seem to be a wild card, with Moses’ wife Zipporah and his father-in-law Jethro/Reuel and brother-in-law Hobab being Midianites (who also intermarried with the Kenites (Judges 4:11)) and being sympathetic to Israel (Exodus 18:9–12; Numbers 10:29). Yet just a short time later (Numbers 22) we see that the princes of Midian conspired with Balak, king of the Moabites, to have Israel cursed. Then they, along with the Moabites, induced Israel to commit Baal worship. But we get no hint from Scripture that the Midianites were some of the mixed multitude who came out of Egypt as they, the Moabites and the Ammonites, were already living in the land of Canaan and the nation of Israel was told not to harass them (Deuteronomy 2:19) so these three peoples were not likely a large part of the mixed multitude during the Exodus.

Several times in Scripture though, the Israelites are told to remember how the Amalekites dealt with them as they came out of Egypt ((Exodus 17:14–15; Deuteronomy 25:17–19; 1 Samuel 15:2). Yet God commands the Israelites to not oppress the stranger or sojourner because they had been sojourners in Egypt (Exodus 22:21, 23:9; Deuteronomy 23:7). The Egyptians seem to be given more latitude than the Amalekites.

As a side note, we also know that the Kenites showed favor to the Israelites right after the Exodus and were later spared when King Saul fought against the Amalekites (1 Samuel 15:5–7), which showed again that the Amalekites tended to associate with Semitic peoples. And had there been a number of Kenites in the mixed multitude exodus group, that would have been all the more reason for the Kenites they met along the way (those still living in southern Canaan) to treat the group favorably (as 1 Samuel 15:6 states they did). Interestingly though, we do get a biblical clue that the Amalekites had been in Egypt and had taken Egyptian slaves.

The Amalekites Did Have Egyptian Slaves in Later History

When David was living in Philistine lands to escape the hand of King Saul, he and his retinue were sent away due to impending war and the distrust of his loyalty by the Philistine lords. He and his army returned to the city of Ziklag only to find it burned down and all the people missing, including two of David’s wives, having been taken captive by the Amalekites (1 Samuel 30:1–5). David and 600 of his men, after receiving affirmation from God that they would catch up to the Amalekite raiding party, set off in pursuit. After crossing the brook Besor, they found a sick Egyptian in a field who was a servant to an Amalekite from the raiding party (1 Samuel 30:11–14). The Egyptian after receiving a promise of safety led the Israelites to the Amalekite raiding party. Verse 16 tells us that this was no ragtag band, they had raided both Israelite and Philistine towns and had come away with a great many goods and captives. Then verse 17 tells us that after David almost completely wiped them out; 400 were still able to escape on camels. This must have originally been a sizable force, possibly several thousand men.

So was this young man an Egyptian by descent who had been in servitude his entire life? Or was he born in Egypt and a recent captive? The Hebrew text here does not necessarily indicate that the young man was born in Egypt; it is possible that he was just of Egyptian heritage and could have been the descendant of slaves from the time of the Fifteenth Dynasty. But since this Amalekite raiding party was a sizable force, it is possible (and more plausible) that they could have also raided posts on the outskirts of Egypt and had taken this young man captive as a boy. One thing is certain though, the text calls this man an Egyptian, and it uses the common term for a person from Egypt (Koehler and Baumgartner 1994, 625). But in either case, we see that at the time of Saul and David, the Amalekites had taken at least one Egyptian captive, and it is likely that this was not an isolated occurrence. Also, we need to remember that this was just a few years after King Saul had decimated the Amalekites (1 Samuel 15:7–8), pursuing and destroying them all the way to the border of Egypt. They must have had an enormous army before that time.

No wonder that the Pharaohs of the Twelfth Dynasty (and later Dynasties up to the Eighteenth) called them wretched and miserable Asiatics. The Amalekites (either alone or with their Semitic or Canaanite allies), by both biblical and Egyptian accounts (if identified with the “Amu”), were able to move and strike quickly, inflict lots of damage, take loot and captives, and then disappear into the desert. They could be struck down again and again and yet like weeds always resurfaced later, all the way to the time of King Hezekiah of Judah (1 Chronicles 4:43). They allied themselves with other Semitic groups and even the Canaanites (Numbers 14:45) when the opportunity for an easy strike on an enemy came up—and to the Egyptians, these alliances of Asiatics were all one group and one threat.

It should be also noted that many Egyptologists think that the Hyksos were likely a confederation of Asiatics comprised mostly of Amorites. While it is certainly possible that the Amorites were a part of the Asiatic confederation that harassed Egypt, and that some were workers or slaves within Egypt, since they were in the land and had several city-state kings (Joshua 5:1, 10:5) it does not seem likely that they were a major component of the mixed multitude which left at the Exodus along with Israel. In fact, it is much more likely that they stayed within Egypt and took over the Nile Delta region once the Red Sea miracle occurred. However, their strength of numbers and the prophetic pronouncement of Genesis 15:13–16 (with verse 16 implying a delayed judgment on the Amorites) could provide a clue about another Egyptian Dynasty.

A Brief Backtrack—What About the Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt?

If you recall from the earlier discussion of the Thirteenth Dynasty, it was a mess from the very beginning although it remained somewhat stable until at least midway through. The south of Egypt (Upper Egypt) was in the process of coming under Kushite Nubian control (technically Nubia was always a threat to Egypt as far back as the reign of Eleventh Dynasty Pharaoh Mentuhotep II). When Egypt went through a second period of division and weakness (mid–late Thirteenth Dynasty), Kushite Nubia was able to take over the Egyptian forts and reoccupy the territory up to the First Cataract at the island of Elephantine and Aswan.12 At the same time, the Nile Delta was revolting and coming under control of “Asiatics.” The Fourteenth Dynasty is conventionally dated usually from either 1780–1650 BC or 1725–1650 BC. The Fourteenth Dynasty rulers had mostly Canaanite names and then added -ra or -re at the end to make them seem more Egyptian, and although 50 lines are allotted on the Turin Canon list only 20 have their full names appear and just nine have any mention of the length of their reigns and/or a contemporary attestation. If the ones with full reigns and attestations are added up, you could get a minimum of 25 years to a maximum of 66 years for the entire Dynasty. And not all Egyptologists are convinced that there is a significant difference between the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Dynasties, nor that all the names listed were actually kings/pharaohs. Ben-Tor, Allen, and Allen, writing in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research conclude that Dynasty 14 and 15 were related and successive.

The numerous Asiatic rulers of the Second Intermediate Period attested by seals from the Delta or Canaan are probably now to be assigned to Dynasty 14 or 15, insofar as they were recognized as kings at all; and the dynasty itself can now be seen as the predecessor of Dynasty 15. (Ben-Tor, Allen, and Allen 1999)

From Ryholt’s work on the primary sources, particularly the Turin king list, it now seems clear that the Second Intermediate Period can be divided into three distinct but overlapping groups of kings. The first of these, comprising most of the 13th Dynasty, is a direct continuation of the 12th Dynasty, and is more properly called Late Middle Kingdom than Second Intermediate Period. The second group consists of the Asiatic rulers of Dynasty 14 and their heirs, the six Hyksos kings of Dynasty 15 . . . The third group consists of Dynasties 16 and 17. (Ben-Tor, Allen, and Allen 1999)

Also of note, the Admonitions of Ipuwer a papyrus typically dated to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty or (more probably) to the mid–late Thirteenth Dynasty describes a chaos which has overtaken Egypt. Asiatics are not simply depicted as enemies outside of Egypt. “Instead, they have come into Egypt and have taken up residence thanks to the power vacuum created by the hypothetical lack of a pharaoh. Their presence has sent the land of Egypt into a downward spiral of inversion and chaos. Their destructive role, moreover, does not stop with their presence in Egypt.” Ipuwer despairs that, “foreigners have become people everywhere.” The term “people” (rmt) was reserved solely for the description of Egyptians themselves. Thus, Ipuwer is lamenting the fact that foreigners have managed to become Egyptians.

Furthermore, the Admonitions of Ipuwer seem to localize this chaos to one region of Egypt (albeit with spillover effects for much of the nation) to the Delta, the very region that Dynasty 14 and the later Hyksos (Fifteenth Dynasty) controlled. “The bird [catchers] have drawn up in line of battle [. . . the inhabitants] of the Delta carry shields . . . Indeed, the Delta in its entirety will not be hidden, and Lower Egypt puts trust in trodden roads. What can one do? No [. . .] exist anywhere, and men say: “Perdition to the secret place! Behold, it is in the hands of those who do not know it like those who know it. The desert dwellers are skilled in the crafts of the Delta” (Mark 2016). It seems clear that a non-Egyptian power is creating chaos in the Nile Delta region possibly as early as the late Twelfth Dynasty and through the end of the Thirteenth Dynasty (Redford 1970, 8).

Mountain Men?

Recalling the earlier quote from The Instruction Addressed to King Merikare, remember that those “wretched Asiatics” were “short of water, bare of wood” because they lived in the mountains (of what is now southern Israel). They are also described as not dwelling in one place, with food being what drove them to migrate or expand their territory. Scripture tells us that the Amorites dwelt in the mountains (Numbers 13:29; Deuteronomy 1:44; Joshua 10:6), had numerous petty kings (Joshua 10:5), were often lumped together (and possibly confederates with) the Canaanites, the Girgashites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Hivites and the Jebusites (Genesis 15:21; Exodus 3:17, 13:5; Deuteronomy 7:1) and were very warlike against any other (especially Semitic) neighbors (Numbers 21:23–26).

Some conventional and biblical archaeologists believe that the Amorites were a significant portion of the Fourteenth Dynasty. Using Egyptologist Kim Ryholt’s chronology, the first ruler of the Fourteenth Dynasty was an Amorite Yakbim (“ia-ak-bi-im”) or at least had an Amorite name. Interestingly several Fourteenth Dynasty kings included the words “bounty” (Merdjefare, Nebdjefare) or “provisions” (Webenre, Nebsenre, Sekheperenre) into their throne names and this seems to indicate that food may have been a very important political factor. According to Ryholt, “Among the prenomina of the immediate successors of Nehsy, it is conspicuous that no less than three are based on the word dß, ‘provisions of food, The fact that ‘provisions of food’ had become a topic of such political importance that it formed the subject of the prenomen, the most important royal name, clearly reveals that there was a shortage of foodstuffs in this period. The archaeological record at Tell el-Dab’a supplements this picture” (Ryholt 1997, 300). Food not only seemed to propel their legs when they were living in the mountains, but also as Pharaohs of the Fourteenth Dynasty. Keeping in mind that this dynasty likely took over a weakened country due to a military but also economic collapse (the result of the ten plagues shortly beforehand), maybe it wasn’t as “good to be the king” as they would have thought.

We also know from Scripture that the Amorites were close to Egypt, living in the southern Judean mountains and that several years (39 according to Ussher) after the Israelites routed the Amalekites, the Amorites attacked them (Numbers 21:21–24). But we don’t need to rely on Ussher alone—as reliable as he might be—since Scripture spells out the numbers for us. Aaron was 123 when he died (Numbers 33:39) and Moses was 120 when he died (Deuteronomy 34:7) and since their ages were only 3 years apart (Exodus 7:7), it is clear that they died within about a year of each other in the final year of the wanderings, which included the defeat of the Amorites. After the death of Aaron, all the events after Numbers chapter 20—of Israel moving on to circle Edom before conquering the area east of the Jordan, including the Amorites under Sihon, happened in the final year of the 40 year wandering period, as is confirmed by Deuteronomy 2:14, which says they crossed over Zered 38 years after leaving Kadesh Barnea. They were nearly a year at Mount Sinai, and it was more than a year after the Exodus that they left Kadesh Barnea after the 12 spies incident. Therefore, we have two biblical witnesses indicating that the battle against the Amorites in the second month of the Exodus and the conquest of the Amorites in the final year of the 40 year wanderings were about 39 years apart.

We read of at least seven kings of the Amorites living in Canaan who Israel defeated, although a remnant of the Amorites survived until the time of Solomon (2 Chronicles 8:7–8) and were put into forced labor. I concur with the conventional identification (although not the conventional chronology) that the Amorites were likely the largest component of the Fourteenth Dynasty. Their proximity to Egypt and apparent expertise in ironwork (Deuteronomy 3:3–5, 3:11, c.f. Deuteronomy 4:46–47) likely allowed them to enter Egypt during the Eleventh or Twelfth Dynasty as skilled laborers. And their warlike nature and their propensity to share power among themselves with several kings, make them ideal candidates for the rulers of the Fourteenth Dynasty.

The Amorites were the Short-Lived Fourteenth Dynasty

But rather than the accepted conventional (and sequential) strung-out dynasty, I propose that most of these kings ruled smaller sections of the Delta concurrently. It is quite possible that there were three “capitals” of the Fourteenth Dynasty, Sais (modern-day Sa El-Hagar),13 Xois (modern-day Sakha) and Avaris (Tell el-Dabca). Concurrent petty kings was how they did it in Canaan, so why change the ruling style that worked for them now that they were in Egypt? As mentioned earlier, the entire Fourteenth Dynasty could be compressed to a minimum of just 25–35 years, and it is likely that they started up immediately after the Red Sea miracle which eliminated the immediate local ruling power—either the last male Egyptian Pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty, or one of the mid–late Thirteenth Dynasty Pharaohs. It should be noted here that when Egypt went through this period of division and weakness (during the late Twelfth through Thirteenth Dynasties), they not only had to deal with the Fourteenth Dynasty coup in the north, but also their southern border was being threatened and Kush (Nubia) was able to take over several Egyptian forts and reoccupy parts of (formerly Egyptian) territory up to the First Cataract. Interestingly enough, Rhyolt mentions that the Fourteenth Dynasty opened diplomatic relations and trade with the Nubians in Upper Egypt shortly after taking over the Nile Delta (Ryholt 1997, 300).

Let’s look back at the biblical textual clues, keeping in mind the REC timeline. The Amorites take control of the Delta region as soon as they hear of the bulk of the Egyptian army drowning in the Red Sea. If this occurred at the end of the Twelfth Dynasty then Sobekneferu, the sister of Amenemhet IV seizes the throne in Thebes due to the absence of any male heir. Keeping in mind that the Egyptians at that time (and in subsequent times when a woman ascended the throne) are highly resistant to the concept of a female Pharaoh and that many were probably still indentured serfs to the crown. It is likely then that there was little initial public outcry at the quick coup in the Delta region. Perhaps the Amorite rulers even sweetened the pot by promising that they would lower taxes and open up land ownership. They also would have had no issue with cutting back or cutting off many of the funds and commodities going to the Egyptian priestly classes.

If, as is more likely, this happened during the Thirteenth Dynasty then the likely surviving Pharaoh candidates were either newcomers to the job (if the reigning Pharaoh had just died in the Red Sea)14 or were frantically fighting a two-front war with a reduced and geographically divided infantry and few chariots. The Amorite Fourteenth Dynasty would have used the same methods discussed above, a quick and practically bloodless coup owing to the fractured state of Egypt at the time. Plus the fact that the entire army of the Delta region had been destroyed (but the Amorites would have been the ones skilled at making weapons for the army, so could have quickly become armed with swords and spears) and many of the Amorites had been living in Egypt for 100 years or more, so knew the best strongholds to occupy and fortify.

Most of the Fourteenth Dynasty rulers added the Egyptian god “Ra” to their names, which probably means that they endorsed Ra above the other gods and likely depleted or raided the temples devoted to Amun, Osiris, Set, Horus, etc. But money and power don’t mean much if you can’t keep yourself and your subjects fed. Recall that Egypt had just been devastated by ten plagues and even the Exodus Pharaoh’s advisers had told him “Do you not yet understand that Egypt is ruined?” (Exodus 10:7). And this was even before the plague of locusts who “ate all the plants in the land and all the fruit of the trees that the hail had left. Not a green thing remained, neither tree nor plant of the field, through all the land of Egypt” (Exodus 10:15).

The Amorites likely needed to set up several kings over small territories to quell outbreaks of rebellion. As mentioned earlier, the conventional chronology states that anywhere from 56 to 76 kings ruled during a period of 75–150 years (depending on the scholar). But if these kings ruled from three capitals, even taking the higher number of 76 kings and running their reigns as concurrent, that this dynasty likely only lasted about 25–35 years (c. 1446–1411 BC) before the Hyksos took over.

Does the Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty Relate to the Fourteenth Dynasty?

While the prevailing thought among some Egyptologists is that the Fifteenth Dynasty was merely a continuation of the Fourteenth, this seems unlikely for several reasons. Once the Fifteenth Dynasty took over, there was only one capital (Avaris) which meant only one king ruling. Also, the Hyksos kings did not simply add -re or -ra to their birth names, they kept those as is but adopted a praenomen (throne name) and in some cases also a Horus name. Their throne name incorporated Ra into the name (it seems that it was politically astute to do this) and gone were any references to food or provision. Now the praenomen boasted of strength and powerful intellect. Khyan’s throne name was Seuser en Ra “The one whom Ra has made strong;” Apophis or Apepi’s throne name was Neb khepesh Ra “Possessor of the strong arm of Ra” and Khamudi’s throne name was Hotep ib Ra “The satisfied one of the mind of Ra.”15 But their Horus names were usually about “pacifying” or “subduing” the “two lands,” referring to Upper and Lower Egypt. It appears that the Fourteenth Dynasty mainly fought to control what was theirs, while the Fifteenth regularly fought with the Egyptian dynasties to the south—the Thirteenth, Sixteenth, and Seventeenth Dynasties, with occasional intervals of peace. Soon after the Fifteenth Dynasty occupied the Nile Delta, they expanded to occupy Itjtawy and then Memphis, leading to the relocation of the Thirteenth Dynasty to Thebes (which the Hyksos also eventually conquered) and then its eventual downfall.

As mentioned earlier, the likeliest candidate for the Hyksos are the Amalekites. They fit the biblical text and the chronological clues given therein. They also fit the time period and biblical Egyptologists, and even some secular Egyptologist models. However, they are not related to the Fourteenth Dynasty, which was primarily Amorite (and thus of Hamitic stock), with perhaps a few other Canaanite confederates thrown in.

What Were the Amalekites Doing for Those 25–35 Years of the Fourteenth Dynasty Rule?

In short, they were licking their wounds. While the Amorites had seized control of the Delta and established the Fourteenth Dynasty, the Amalekites were recovering from the devastating loss they suffered at the hands of the Israelites (Exodus 17:13). When you consider that most of their warriors who died were also those of the most viable reproductive age, it is easy to see it would take a generation to replace the numbers that they had lost. While Israel wandered around the wilderness, and the Amorites reigned, both in Egypt and in Canaan, the Amalekites slunk back to their homes in northern Negev, Canaan, and Syria, waiting to grow powerful enough to fight again.

Once they did grow powerful enough, they noticed that the Delta region of Egypt was ripe for the taking, and that any revenge they had in mind against Israel could wait, and indeed they may have lost track of Israel as they wandered the Wilderness. By this time, Delta crops had been growing again and the land had rebounded. The Fourteenth Dynasty had been at war with the Thirteenth ruling from Itjtawy (and then later Thebes) from the beginning. The time was right to attack the weakened Fourteenth Dynasty. Keeping in mind that the Amorites had attacked other Semitic peoples in the past; the Moabites (Numbers 21:26), Israelites (Numbers 21:23), and quite possibly the Ammonites (Numbers 21:24 and Deuteronomy 3:11) it may also be likely that any Amalekites still living in Egypt had been put under hardship by the Amorite Fourteenth Dynasty. Any Semitic peoples still living in Egypt may have assisted the Amalekite Hyksos invasion from the inside.

But from an Egyptian perspective, it was just one group of Asiatics fighting with another. And in regard to the Tell el-Dabca study, recall that it only differentiated those growing up in the Delta region from those outside it. Most or all of the Fifteenth Dynasty were “outsiders,” and the influx of Amalekite conquerors was probably approximately offset by the exodus of the Amorites of Fourteenth Dynasty, (many of which had been in Egypt as skilled laborers before becoming the ruling class) who would have been considered part of the local Delta population by this time. Many of the Amorite Fourteenth Dynasty probably fled back to the hill country of their homeland. And before long the predictive prophesy of Genesis 15:16 was fulfilled, those who weren’t killed by the Amalekites’ invasion were killed just a short time later (4–14 years) when they attacked the Israelites in Numbers 21:21–35.

Interestingly enough, one could even view the Amalekite Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty wiping out the Amorite Fourteenth Dynasty as a secondary fulfilment of Genesis 15:16. God promised that Abraham’s descendants would return to Canaan, the Promised Land and implied in the same verse that judgment would come upon the Amorites at that time. “After four generations they will return here to this land; for the wickedness of the Amorite nations living here now will not be ready for punishment until then” Genesis 15:16 NLT).16 Amalek routed the Amorites in Egypt (burning their temples, enslaving them and chasing their armies out of Egypt, just as Manetho had said), while Israel wiped out or dispossessed the Amorites in Canaan: and both of these would have occurred within a few years of each other. Looking again at the timing of the Fourteenth Dynasty in a REC (c. 1446–1411 BC), any survivors would have fled Egypt in 1411 BC and returned to their ancestral homelands, just 4–5 years before the Israelites wiped out their cities on the east side of the Jordan.

My Kingdom for a Horse?

Perhaps the biggest challenge against a late Twelfth to late Thirteenth Dynasty Exodus is the passage about Pharaoh chasing the Israelites with 600 chariots after he had let them go following the tenth plague (Exodus 14:5–9), and not just 600 chariots, but 600 choice chariots plus all the other chariots of Egypt and horsemen. Many Egyptologists believe that the Egyptian rulers did not utilize chariots in battle until during and after the time of the Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty. Even some creation researchers have made this assertion (Bates 2020). When it is pointed out that chariots are mentioned in Egypt during the reign of the Pharaoh of Joseph’s time (Genesis 41:43, 46:29, 50:9), when Joseph became vizier, which was 219–224 years prior to the Exodus (using the short sojourn) 219 years (seven years of plenty plus two years of famine before Israel came in, then a 210 year sojourn in Egypt), 224 years if you go with 215 year sojourn in Egypt for Israel. This is based on the 400 years of sojourning promised for Abraham’s descendants beginning with Isaac’s birth. Isaac was 60 when he had Jacob (Genesis 25:26) and Jacob was 130 when he entered Egypt (Genesis 47:9), leaving 210 years in Egypt to get to the 400. Some have even postulated that this pushes Joseph forward to the time period of the Hyksos (Fifteenth Dynasty) stating: “So, was Joseph riding his chariot either 200 or 400 years (depending upon one’s view of how long the sojourn was) before the Hyksos arrived? Genesis 41:43 is strong evidence that the Hebrew sojourn and subsequent Exodus could not have been before the Hyksos occupation” (Bates 2020). While this might be what we hear espoused from secular Egyptologists and liberal biblical archaeologists (if they believe there ever was an Exodus) it is rather shocking to hear it from a biblical creationist.

Even placing the Exodus 224 years after the conventional dating of the Hyksos (1650 BC is the most common date given for the beginning of their dynasty) and allowing time for Joseph riding as “second ruler in the kingdom” in the chariot, Israel’s entrance into Egypt, and the Pharaoh who did not know Joseph arising in Egypt gives us an Exodus at 1426 BC (at the earliest) and 1150 BC at the latest (for a long sojourn), and this is assuming (using conventional Egyptian chronology) that Joseph arrived in Egypt just as the Hyksos took over the Nile delta. These dates are already too late (and would be later still if Joseph entered Egypt 50 years into the Hyksos dynasty) and conflict with later biblical history (the period of the Judges and the United Monarchy, for example). Ironically though, the same author seems to adhere to a 1446 BC Exodus (Bates 2014). How one can hold to the Israelites arriving in Egypt after the Hyksos came to power and still having an Exodus at 1446 BC seems to be an untenable position chronologically under conventional Egyptian chronology and the typically proposed RECs. Patrick Clarke, also writing for the same organization, places Joseph in the Eleventh Dynasty under Mentuhotep II’s reign using a REC date of 1757–1706 BC (Clark 2013). That would place the Exodus (assuming Clarke’s 250–300 year revision carried down) in the early Thirteenth Dynasty in 1446 BC.

And how ironclad is the argument that the Egyptians had no skill with chariot warfare and/or war chariots before the arrival of the Hyksos? Admittedly this is a common theme in many histories of Egypt resources, but how accurate is it? It should be noted that recent archaeological findings are providing insight that this may not be the case.

Horse and mule bones have been found in the northern Levant at Nahal Tillah, Afridar, and Arad in central/southern Israel and at Tall al-Umayri in Jordan near the northern edge of the Dead Sea that conventionally date to 3000 BC (Grigson 2012). Horse remains were found in the Sinai at Heboua (Raulwing and Clutton-Brock 2009, 42) conventionally dated to the Second Intermediate Period (1786–1552 BC).

Chariots with spoked wheels, drawn by bitted horses, were used as platforms for archery in images from Old Syrian seals dating to 1800–1600. As the draft animals for chariots, horses gained a new and important role in the Near East and Egypt. A horse with wear on its premolars, probably from a bit, was buried shortly before the destruction of the Middle Kingdom fortress at Buhen, Nubia, dated about 1675 BCE (Anthony 2013).

The lack of chariots found in Egypt before the Eighteenth Dynasty is not all that surprising since they were made mostly of wood and leather. Also consider that the few chariots which have been found were located in pristine tombs (like Tutankhamen’s) which had been sealed off from the forces of water, wind, sand, and the hands of grave robbers. According to one scholar:

The foregoing makes it clear that according to that scholar: 1) there is an intrinsic difficulty with survival of evidence of early wheeled vehicles; 2) wagons with tripartite disk wheels were in existence by 3030 BC; and 3) this technology spread far and fast. Given these three facts, the problem of proving that the highly advanced civilization of Old Kingdom Egypt did not have wheeled military vehicles a full 580 years after the invention and spread of the tripartite wheel seems to be a very much greater one than that of proving that she did. (Tatomir 2014, 327)

Biblically, the argument also makes little sense. Consider that within 40 years of the Exodus, Deuteronomy 20:1 tells us that God, speaking to the children of Israel admonishes them, “When you go out to war against your enemies, and see horses and chariots and an army larger than your own, you shall not be afraid of them, for the LORD your God is with you, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt.” It seems certain that God is forewarning them that the Canaanites already had horses and chariots and had been skilled for some time in their usage in war. Are we then supposed to seriously entertain that the petty kings of minor nations within a few days’ walking distance of Egypt had these things and the then-most powerful nation on earth did not? That simply strains credulity.

Additionally, the argument that the composite bow was not known in Egypt until the time of the Hyksos seems to be falling out of favor.

Texts of the eighteenth-century B.C. from Mari [Syria] reveal that composite bows were regular combat weapons there. In at least one case both self and composite bows are listed as part of an issue including a two-wheeled chariot. (Moorey 1986, 210)