The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

Archaeology has not yet uncovered a large number of artifacts to directly support Jesus’s resurrection. However, though few, the sites and artifacts uncovered by archaeology are rich in meaning and significance. This paper will discuss seven archaeological discoveries and sites related to the resurrection of Jesus Christ: (1) the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, (2) the Garden Tomb, (3) the rolling-stone tombs of the first century AD, (4) the remains of Jehohanan son of HGQWL, (5) the Alexamenos graffito, (6) the Megiddo Mosaic Inscription, and (7) the Nazareth Inscription. Taken together, these archaeological finds (minus the Garden Tomb) are indirect evidences which build a cumulative case supporting the biblical account of Jesus’s resurrection.

Keywords: Akeptous Inscription, Alexamenos graffito, Archaeology, Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Constantine, Crucifixion, Eusebius, First-Temple tombs, Garden Tomb, Greek island of Kos, Jehohanan son of HGQWL, Jerome, Jerusalem, Jesus’s resurrection, Joseph of Arimathea, Josephus, Kathleen Kenyon, Megiddo Mosaic Inscription, Muristan, Nazareth Inscription, Rolling-stone tombs, Second-Temple tombs, St. Étienne Tomb Complexes, Tertullian

Introduction

The resurrection of Jesus is one of the core foundations of the Christian faith. Indeed, Paul says that “if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14, ESV).1 Archaeology confirms several details given in Scripture concerning the resurrection and, therefore, demonstrates the accuracy, defensibility, and historicity of the biblical account.

This paper will discuss seven archaeological discoveries and sites related to the resurrection of Jesus Christ: (1) the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, (2) the Garden Tomb, (3) the rolling-stone tombs of the first century AD, (4) the remains of Jehoḥanan son of ḤGQWL , (5) the Alexamenos graffito, (6) the Megiddo Mosaic Inscription, and (7) the Nazareth Inscription.

All of these discoveries and sites (minus the Garden Tomb) provide indirect evidence for the plausibility of the resurrection account. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre (1) and the Nazareth Inscription (7) are more directly related to the resurrection than the others; while, items (3), (4), (5), and (6) are more indirectly related. Although indirect, taken together, these seven particulars provide a strong cumulative case for Jesus’s resurrection.

Biblical Details of the Resurrection of Jesus

Before looking at the two purported sites of Christ’s death, burial, and resurrection, the details given in Scripture concerning these events will be briefly stated. These details will be discussed in more detail throughout the following sections.

- Jesus was crucified in a place called Golgotha in Aramaic, meaning “Place of a Skull” (Matthew 27:33; Mark 15:22; Luke 23:33; John 19:17).

- Jesus’s crucifixion took place outside of the city gates (Hebrews 13:12).

- Jesus was scorned by those who passed by while He hanged from the Cross (Matthew 27:39; Mark 15:29).

- Jesus was crucified near the city (John 19:20).

- A garden existed in the place where Jesus was crucified (John 19:41).2

- Jesus’s tomb was located “close at hand” (ESV) or “nearby” (NASB95, NIV, NET, HCSB)3 inside this same garden (John 19:41).

- Jesus was buried in the tomb of a rich man named Joseph of Arimathea (Matthew 27:57–60).

- Jesus was buried in a new tomb (Matthew 27:60; Luke 23:53; John 19:41).

- Jesus was buried in a tomb where no one else had ever been laid (Luke 23:53; John 19:41).4

- Jesus’s tomb was hewn out of rock or stone (Matthew 27:60; Mark 15:46; Luke 23:53).

- A “great stone” (ESV) was rolled across the entrance of Jesus’s tomb to seal it (Matthew 27:60; Mark 15:46, 16:4).

- Jesus’s sepulcher-sealing stone was rolled away by an angel who then sat on it (Matthew 28:2; Mark 16:4; Luke 24:2; John 20:1).5

- Mary Magdalene went into Jesus’s tomb after he had risen and “saw two angels in white, sitting where the body of Jesus had lain, one at the head and one at the feet” (John 20:11–12).

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre

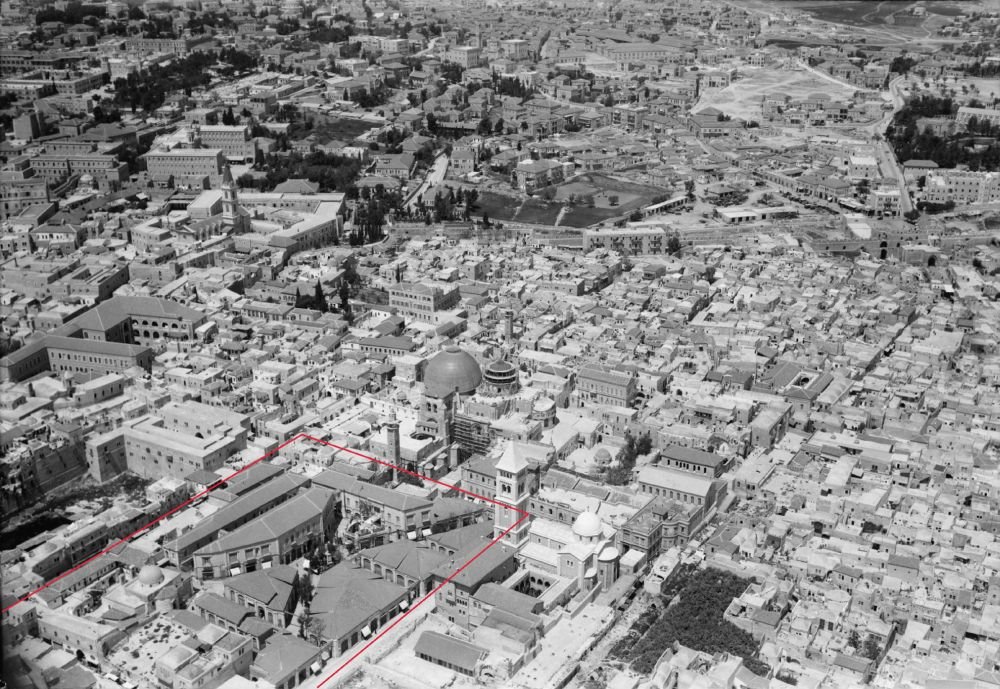

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is traditionally recognized as the site of Jesus’s death, burial, and resurrection (see figs. 1–3). It is located west, northwest of the Temple Mount (see figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 1. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—courtyard and main entrance on southern side. Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/larrywkoester/36622595883/in/album-72157689253203885/, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 2. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—above courtyard and main entrance. Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/larrywkoester/37292411861/in/album-72157689253203885/, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 3. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—looking west to east. Photo taken by Noam Chen for the Israeli Ministry of Tourism, https://www.flickr.com/photos/israelphotogallery/14645657726/, CC BY-ND 2.0.

Fig. 4. Aerial view of the Temple Mount from the Mount of Olives. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is circled in red. Godot13, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Temple_Mount_(Aerial_view,_2007)_07.jpg, artwork added by Matt Dawson, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Fig. 5. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre—as seen from the Mount of Olives with the Dome of the Rock in the middle distance. Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/larrywkoester/36606164233/in/album-72157689253203885/, CC BY 2.0.

Background

Ousterhout (1989, 66) describes the significance of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre:

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem was one of the most important buildings of the Middle Ages, marking the traditional sites of Christ’s Crucifixion, Entombment and Resurrection . . . Its position was regarded as the center of the world, as the events it commemorated were central to Christian thought. It was the object of countless pilgrimages and the ultimate inspiration for the Crusades.

Eusebius (ca. AD 260–339) records that Constantine, who reigned from AD 305–337, “judged it incumbent on him to render the blessed locality of our Saviour’s Resurrection an object of attraction and veneration to all. He issued immediate injunctions, therefore, for the erection in that spot of a house of prayer: and this he did, not on the mere natural impulse of his own mind, but being moved in spirit by the Saviour himself” (1890, 527).6 Eusebius (527)7 describes how “impious men,” had previously brought in much dirt to cover the entire spot of the tomb and crucifixion, paved the top with stone, and then built “a gloomy shrine of lifeless idols to the impure spirit whom they call Venus, and [offered] detestable oblations therein on profane and accursed altars.” Though Eusebius does not specify these “impious men,” Jerome (ca. AD 346–420) identifies Emperor Hadrian:

From the time of Hadrian to the reign of Constantine—a period of about one hundred and eighty years—the spot which had witnessed the resurrection was occupied by a figure of Jupiter; while on the rock where the cross had stood, a marble statue of Venus was set up by the heathen and became an object of worship. The original persecutors, indeed, supposed that by polluting our holy places they would deprive us of our faith in the passion and in the resurrection.8 (1893, 120)9

Since Hadrian died in AD 138, the latest that the pagan temple could have been erected is roughly one hundred years after the death of Christ (ca. AD 30– 33).

Constantine ordered that the pagan shrine erected by Emperor Hadrian over the tomb of Christ be destroyed (as recorded by both Jerome and Eusebius). When he did this, he was surprised to find that the tomb was miraculously still intact underneath the mound: “As soon as the original surface of the ground, beneath the covering of earth, appeared, immediately, and contrary to all expectation, the venerable and hollowed monument of our Saviour’s resurrection was discovered” (Eusebius 1890, 527).10 Thus, in AD 330, Constantine and his mother Empress Helena built a “house of prayer worthy of the worship of God” (528),11 which was to be more beautiful than all the other churches of the world to commemorate the place of Jesus’s tomb and resurrection. Constantine built a mausoleum (called the Anastasis, the Greek word for resurrection) to commemorate the tomb of Christ and the Martyrium Church (Martyrium is the Greek word from which the English word martyr is derived) to commemorate Golgotha.12 An outdoor courtyard separated these two structures. Archaeology has uncovered some of the remains of the “Constantinian complex,” thus validating the writings of Jerome and Eusebius (Ousterhout 1989, 2003).

Also, in 2015, “the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) was invited by His Beatitude, Patriarch of Jerusalem Theophilos III, to implement an ‘Integrated Diagnostic Research Project and Strategic Planning for Materials, Interventions Conservation and Rehabilitation of the Holy Aedicule of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem’” (Moropoulou et al. 2018, 81–82). The Aedicule/ Edicule is a small structure within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre which was built around the remains of the burial tomb of Jesus and serves as a shrine to commemorate and protect this holy site (see figs. 6–10). This restoration was completed in March 2017 (82). During the rehabilitation and restoration, “Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) was employed for the archaeometric analysis of mortars selected from different areas of high historical and architectural interest, aiming to shed light on the construction phases of the Holy Aedicule” (82). On top of burial rock inside the Edicule that is purported to be the bedrock upon which Christ was laid, are several layers. First (from top to bottom), is an amber-hued marble plate, then a layer of filling material, then a grey marble plate, then a layer of bedding mortar, then the burial bedrock (83). One mortar sample was taken from the bedding mortar between the burial bedrock and the grey marble plate. This sample dated to AD 345 (± 230) (89, table 5). This date provides additional confirmation to the testimony of Eusebius and Jerome that Constantine built a holy structure to commemorate the tomb of Jesus: “The mean, centered OSL dating estimation of the fragmented grey marble plate’s bedding mortar to middle 4th c. CE (345 CE) indicates that the rock burial surface, on which the body of Jesus Christ is believed to have been laid, was encased in marble early on, at least on the top, already from the Constantinean era” (88).

Fig. 6. Edicule—left side. Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/126110866@N08/39322732861, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 7. Edicule—aerial. Photo by Mordagan for the Israeli Ministry of Tourism, https://www.flickr.com/photos/israelphotogallery/14511647940/in/photolist-o7kZmy-LcWJ4-LcGzb-M9Phq-2iCFBUULcFR5-LcE9o-LcSpM-M9W4M-cKnR1w-VgAzzBLdioM-ooJb1b-LcRme-M9W2B-LcEMc-VgBs6B-csnVf-WrzZn3-2bcNfPN-Wix3fX-VUUiHq-Wvdifr-LcH4c-WrzH8j-LczZf-LcQpK-VdTcz9-LcMQD-8bkYqh-LcxCw-Wrxtuw-LcqHu-LcKL4-WvhQSX-LcwVG-LcujS-eUhbKXTzRGos-VgCVe2-LcGgx-LcFvx-piJ8sB-VPkbLG-LcK7PVgFmZ6-Ldht4-VyX9jv-QTHCK8-VgB7Lz, CC BY-ND 2.0

Fig. 8. Edicule—front. Seetheholyland.net, https://www.seetheholyland.net/church-of-the-holy-sepulchre/, © Seetheholyland.net.

Fig. 9. Edicule—front entrance. Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/larrywkoester/36582297784/in/album-72157689253203885/, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 10. Edicule—upper front entrance under dome. Bahnfrend, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aedicule,_2019_(02).jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0.

In AD 614, “the Persians destroyed parts of the [Constantinian] complex” with fire (Moropoulou et al. 2018, 80). Later, some reconstruction and repairs took place under Patriarch Modestos (80). However, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre would later suffer great damage under Calif al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah in AD 1009:

Matters went from bad to worse with the accession of Calif al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (ruling 996–1021),who exhibited a clearly hostile attitude toward the Christians. He ordered random arrests, executions, and the destruction of churches as early as 1001. In 1004 he decreed that the Christians could no longer celebrate Epiphany or Easter. Finally, on 18 October 1009, al-Hakim ordered the destruction of the Holy Sepulchre and dependent buildings, apparently outraged by what he regarded as the fraud practiced by the monks in the “miraculous” Descent of the Holy Fire, celebrated annually at the church during the Easter Vigil. According to the chronicler Yahia, only those things that were too difficult to demolish were spared. Processions were prohibited, and a few years later all of the convents and churches in Palestine were said to have been destroyed or confiscated. (Ousterhout 1989, 69)

Thirty-three years later in 1042, Constantine IX Monomachus became emperor of Byzantium and rebuilt the church (Ousterhout 1989, 70). In 1099, the Crusaders captured Jerusalem and the church. The Crusaders expanded the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and dedicated it in 1149. Most of what is standing today is from the time of the Crusaders (68).13

Archaeological Features

Bahat (1986, 26) explains that the Armenian, Greek, and Latin religious communities have been responsible for the care and restoration of the church since 1960. Furthermore, “in connection with the restoration, they have undertaken extensive archaeological work in an effort to establish the history of the building and of the site on which it rests. Thirteen trenches were excavated primarily to check the stability of Crusader structures, but these trenches also constituted archaeological excavations” (26). Bahat (26) tells that “Father Corbo has been intimately involved in this archaeological work for more than 20 years, and no one is better able to report on the results than he.” Although Corbo wrote his volumes in Italian, Bahat relays Father Corbo’s findings.

A Limestone Quarry

The area on which the Church of the Holy Sepulchre rests is a quarry of high-quality meleke limestone dating from the ninth to eighth centuries BC (Broshi and Barkay 1985, 118). The Israelites would have used this quarry in building projects during the late Judean monarchy. The dating of the quarry is secure since the fill above the quarry is filled with pottery shards and ostraca dating from the eighth to the sixth century BC (Iron Age II) (112). This limestone quarry extends beyond the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to the surrounding areas: “Traces of the quarry have been found not only in the church area, but also in excavations conducted nearby in the 1960s and 1970s—by Kathleen Kenyon, in the Muristan enclave of the Christian Quarter, and by Ute Lux, in the nearby Church of the Redeemer” (Bahat 1986, 30). Price (1997, 314) explains how the quarry was eventually rejected, turned into a refuse dump, and then later used as a burial site by the first century BC: “Excavations intended to expose more of this rock have revealed that it was a rejected portion of a pre-Exilic white stone quarry, as evidenced by Iron Age II pottery at the site . . . . By the first century BC this rejected quarry had gone from being a refuse dump to a burial site.”

A Garden and Cemetery

Archaeology has confirmed that the site of the Holy Sepulchre was transformed into a garden at the beginning of the first century BC. Bahat (1986, 30) states,

According to Father Corbo, this quarry continued to be used until the first century B.C. At that time, the quarry was filled, and a layer of reddish-brown soil mixed with stone flakes from the ancient quarry was spread over it. The quarry became a garden or orchard, where cereals, fig trees, carob trees and olive trees grew. As evidence of the garden, Father Corbo relies on the fact that above the quarry he found the layer of arable soil.

Another important archaeological fact concerning the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is that during the first century BC, the quarry not only became a garden, but it also became a “large burial ground” (Bahat 1986, 32). Jesus’s purported tomb within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is an arcosolium, “a shallow, rock-hewn coffin cut lengthwise in the side of a burial cave,” with an arched ceiling above the recess (31) (see fig. 11). A quadrosolia (see fig. 12) occurs when “the niche is rectangular, with a straight top” (Kloner 1999, 24). Although Jesus’s tomb itself was destroyed and cut down to the bedrock by the command of Calif al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah in 1009, remnants of the tomb remain within the Edicule. Bahat (1986, 31–32) notes that the tomb attributed to Jesus is “composed of an antechamber and a rock-cut arcosolium. Unfortunately, centuries of pilgrims have completely deformed this tomb by pecking and chipping away bits of rock as souvenirs for their reliquaries. Today the tomb is completely covered with later masonry, but enough is known to date it as an arcosolium from about the turn of the era.” Jesus’s tomb being an arcosolium matches the details given in Scripture:

Fig. 11. Arcosolium—Southeast Monastery, Deir Sem’an, Syria. Arcosolia came in a variety of styles. One style (as seen in this image) was formed by cutting a cavity into the rock beneath the arch. A large stone (or several stones) would then be placed over this opening to seal the tomb. Other arcosolia had a flat burial shelf carved out under the arch to allow for an ossurary to be placed upon the flat surface later. Frank Kidner, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Southeast_Monastery,_Deir_Sem%27an_(%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%B1_%D8%B3%D9%85%D8%B9%D8%A7%D9%86),_Syria_-_Arcosolium_tomb_east_of_south_building_-_Dumbarton_Oaks_-_PHBZ024_2016_2094.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Fig. 12. Quadrosolia—Capodimonte Catacombs. Quadrosolia are best seen on the left-hand side of image. A combination of an arcosolium and quadrasolia are seen on the right. Historic Mysteries, https://www.flickr.com/photos/comandosupremo/31082061184/in/photolist-PmBFUC-4as4dm-4anZqF-4anMCD-4anMcB-4anZez-4arNxJ-4arCyq-4anzHV-9rP4tW-24m8Uir-24m8U5F-24m8TKT-22YQfTZ-2a2UoR5-4as2Rm-4anKYp-22YQfE2-4arCWY-4arJ2y-24m8Usp-6eNtUA-24m8VTv-aB2uCV-4arBEj-4arGNb-wyASNZ-Gdhwmf-4arLC3-4anzgP-4arBWY-oq5LYq-Rs1sTt-jt2D1a-24m8Vpp-24m8UnK-F4AbHj-4anH4K-4arAmh-4anL7V-4anHJz-4arV6J-6eJjU4-4ao4fD-GdhwJu-4arKjb-4anzrT-4ao17Z-4arCL3-24m8VDx, CC BY-SA 2.0.

These types of tombs were reserved for those of wealth and high rank. This seems to be the type of tomb in which Jesus was laid because Jesus’ tomb was said to be a wealthy man’s tomb (Matthew 27:57–60; cf. Isaiah 53:9), the body could be seen by the disciples when it was laid out (possible only with a bench-cut tomb—John 20:5, 11), and the angels were seen sitting where both Jesus’ head and feet had been (John 20:12). . . . the so-called Tomb of Jesus at the traditional site, though deformed by centuries of devoted pilgrims, is clearly composed of an antechamber and a rock-cut arcosolium. (Price 1997, 314)

Corbo (1992, 1071) agrees with Price that only an arcosolium could allow for two angels to sit where Jesus’s head and feet had been (John 20:12). This would not have been possible with quadrosolia or kokhim (discussed in the following paragraph).

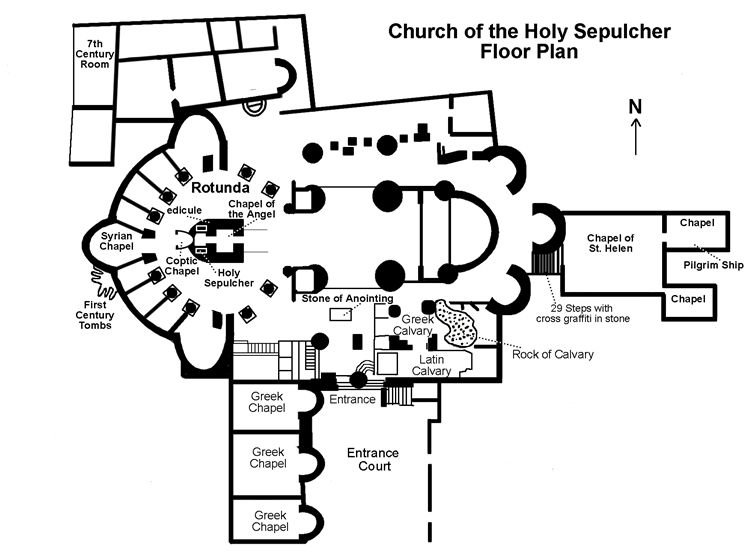

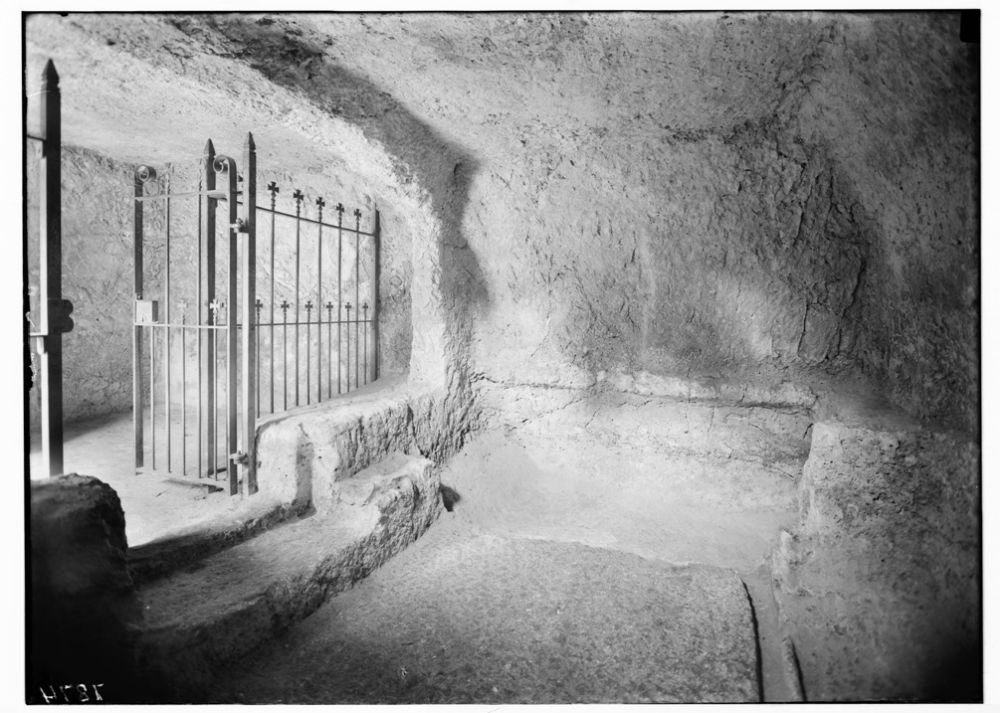

In addition to Jesus’s tomb, other tombs are also present inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Two kokhim (see figs. 13–14), “long, narrow recesses in a burial cave where either a coffin or the body of the deceased could be laid” (Bahat 1986, 32), are located beneath the rotunda, west of the Edicule (see fig. 15). Bahat (30) notes that at least two other kokhim have been found at the site. Several other tombs would have undoubtedly existed that have not survived to the present day.

Fig. 13. Second Temple kokhim tombs—Mt. Scopus. Derek Winterburn, https://www.flickr.com/photos/dnwinterburn/8620360222/, CC BY-ND 2.0.

Fig. 14. Kokhim—Tombs of the Kings, Paphos, Cyprus. Some of the tombs at the Tombs of the Kings date to the early fourth century BC. martin_vmorris, https://www.flickr.com/photos/martin55/37140482214/in/photolist-bnk844-7stHPJ-CNaVda-cwWVwm-CpgLAR-7stnA1-5t8kBJ-8hzgy1-5t8jsJ-5t8wts-5t47iK-5amgNb-5t8WYh-277cwns-9rXRoo-PisFzH-gqK2Qr-DjmdX5-bJjFCr-FC52yM-FHVSED-mEXaQ8-PqnTWu-5atGcH-4L7K98-DmENat-5axUGu-7stFtf-Cp9Jzb-nsRAPP-DeozNz-FzKD5h-Dc6ods-DjmsKq-5amkdw-CNaJ8p-DmEKvv-CpgNCg-7spnQe-hTdG8G-gqJq9j-YzYFpC-YzYGP1-YzYJhS-ZBTxsU-ZBTAcG-DmEAJ2-Dc6BWj-PisHAr-gqJTy6, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Fig. 15. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—2 kokhim west of the edicule. Derek Winterburn, https://www.flickr.com/photos/dnwinterburn/8671192499/in/album-72157629056988243/, CC BY-ND 2.0.

The archaeological evidence that the quarry became a garden and cemetery during the first century BC is significant because John 19:41–42 states that “in the place where [Jesus] was crucified there was a garden, and in the garden a new tomb in which no one had yet been laid. So because of the Jewish day of Preparation, since the tomb was close at hand, they laid Jesus there.” These verses teach (1) that Jesus’s tomb was in a garden (see also John 20:15), (2) that the tomb was close to the place of the crucifixion, and (3) that the tomb was a new tomb.14

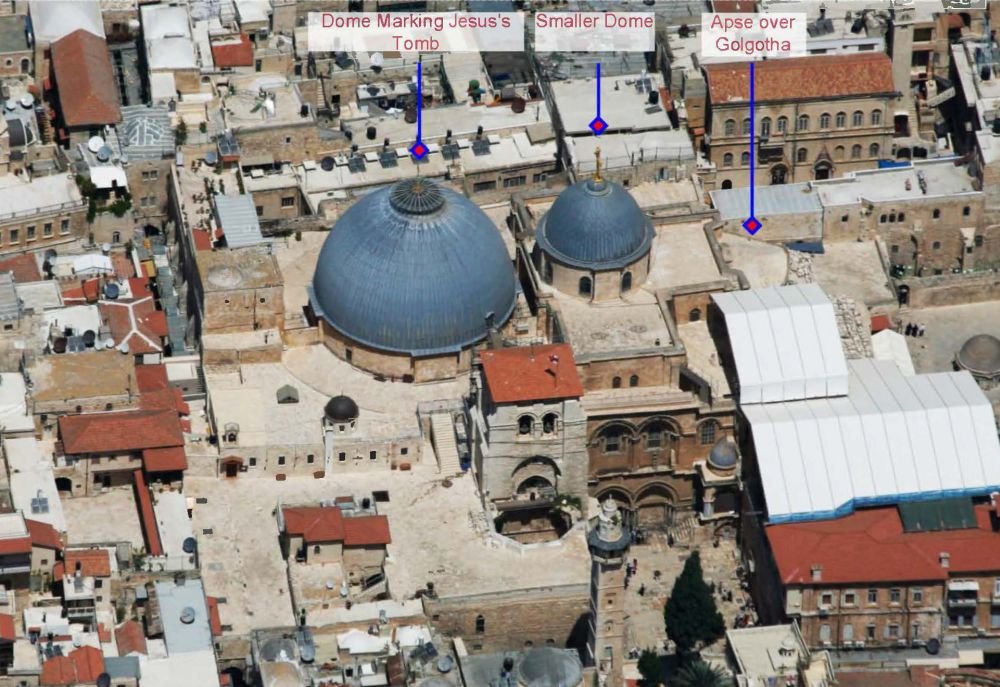

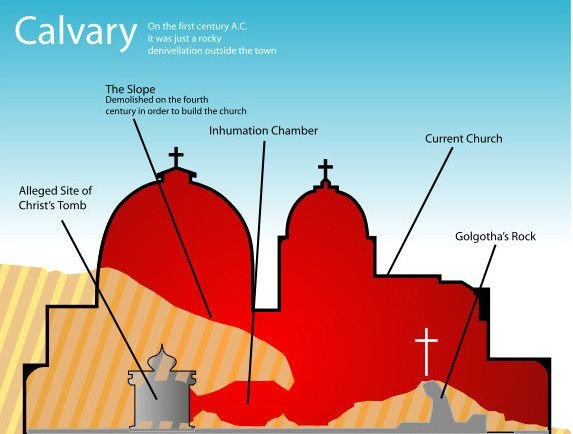

Upon entering the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, immediately to the right, is a narrow staircase that leads visitors to the purported site of Jesus’s crucifixion (see fig. 16). Here, encased in a protective glass, is a stone venerated as the stone upon which the Cross of Christ was erected (see figs. 17–20). Kramer (2020, 108–114) contends, however, that “the far older tradition” marks Golgotha’s location under the smaller apse of the Holy Sepulchre. In addition to referencing ancient texts, Kramer (2020, 114) visually demonstrates that when the current Church of the Holy Sepulchre is transposed over the previous Martyrium Church built by Constantine, the smaller apse of the Holy Sepulchre and the apse of Constantine’s original church sit perfectly one-on-top-of-the-other and mark the same spot, “identifying and commemorating it as Golgotha” (see figs. 21 and 22).15

Fig. 16. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—steps leading to Calvary. As visitors climb the steps, they are said to be ascending the “hill of Calvary” or Golgotha. Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/larrywkoester/36582566554/in/photolist-XVZxBM-Mp16Ah-boA1Mx-2j44ZMe-E6qhUM-hsSHPG-gLFrzw-hsThr4-hsUAsT-6anm6Z-6anm72-6awCPN-hsS5hD-hsPHJt-MP2fW-hsRTRt-bbSfq2-bbScTP-bbSdAX-bbSeLP-bbSecv-hsLLmY-hsMUi9-hsN1HU-hsMqCX-hsQm4U-hsPLZg-7wMaKZ-hsQzDC-M9VSB-L2SHJ-xcQgZR-x7oFM8-28i68oF-hsPfte-hsLZmf-hsNwtU-M9W8F-hsLd8F-hsMxhD-XJFdw7, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 17. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—Greek Orthodox and Latin Calvary. The Greek Orthodox Chapel of the Crucifixion is on the left, and the Latin altar in the Catholic Chapel of the Nailing of the Cross is on the right. The section on the left belongs to the Greek Orthodox Church and is therefore called the Greek Orthodox Calvary; while, the section on the right belongs to the Catholic Church and is named the Latin Calvary. Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/larrywkoester/37262939522/in/album-72157689253203885/, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 18. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—Greek Orthodox Calvary. The “Rock of Calvary” is clearly seen in the image. Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/larrywkoester/37036387080/in/album-72157689253203885/, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 19. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—Greek Orthodox Calvary (close). Seetheholyland.net, https://www.flickr.com/photos/seetheholyland/4286448005/, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Fig. 20. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—Rock of Calvary. Beneath the Greek altar is a silver disc that marks the place where the Cross was supposedly erected. A hole in the disc allows visitors to touch the limestone rock. Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/larrywkoester/37292413011/in/album-72157689253203885/, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 21. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—above courtyard and main entrance (with identifiers). Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/larrywkoester/37292411861/in/album-72157689253203885/, text and artwork added by Matt Dawson, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 22. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—aerial of three apses (with identifiers). אילן ארד , https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Church_of_the_Holy_Sepulchre_-_Ilan_Arad.jpg, text and artwork added by Matt Dawson, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Outside the Walls of Jerusalem

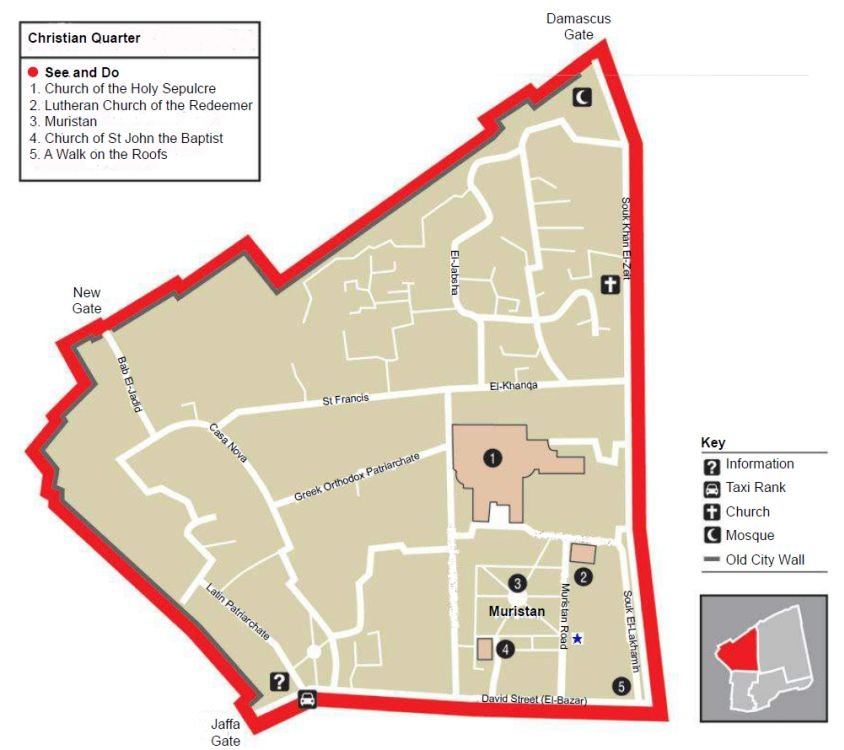

The Bible clearly states that Jesus Christ was crucified and buried outside of the walls of Jerusalem (John 19:20; Hebrews 13:11–12). An early argument against the validity of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was that it was inside the modern city walls of Jerusalem. Kenyon (1974, 227) resolves this objection: “The answer, of course, is that the walls of the present Old City are not those of the time of the Gospels.” Kathleen Kenyon performed several archaeological digs in Jerusalem between 1961–1967. One of Kenyon’s excavations took place in the area of Muristan, “immediately to the south of the Holy Sepulchre,” at a location called Site C (227) (see figs. 23 and 24). At Site C, beneath the Byzantine levels, Kenyon (228) discovered a major fill comprised of alternating layers of late-seventh-century BC and first-century AD material: “It was clearly a single fill derived from two different sources.” However, some pottery belonging to the second century AD was also discovered. Therefore, Kenyon (230) dated the fill to the time of the “Hadrianic reconstruction of Jerusalem, for it is, of course, dated by the latest material in it.” Below the main heterogenous fill, is a layer that is dated to the seventh century BC, with a quarry beneath that (230). Weighing all the data, Kenyon (230–231) concludes:

One can say with some confidence that quarrying would not have taken place within the closely builtup confines of an oriental city in the first millennium BC, though it has been shown above that it could take place under the authority of an autocrat like Herod the Great in circumstances in which he was trying to bring Jerusalem into the Romano-Hellenistic world that he admired. I feel that one can say with confidence that this seventh-century BC quarry indicates that the area of our Site C was outside seventh-century BC Jerusalem. The fact that nothing intervened between the seventh-century BC surface and the second-century A.D. fill creates a strong suspicion that throughout this time the area of Site C remained outside the occupied area, and therefore presumably outside the walls.

Fig. 23. Jerusalem Old City—Christian Quarter. Muristan is almost due south of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The blue star was added to show a rough approximation of Kathleen Kenyon’s Site C. David Bjorgen, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jerusalem_Christian_Quarter.jpg, artwork added by Matt Dawson, CC BY-SA 1.0.

Fig. 24. Aerial photo of the Old City taken in 1931. Muristan is in red. This photo was taken in 1931 before Kenyon’s archaeological digs between 1961–1967. Library of Congress, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Air_views_of_Palestine._Jerusalem_from_the_air_(The_Old_City)._Jerusalem._Church_of_the_Holy_Sepulchre._Showing_Church_of_the_Redeemer_and_the_Muristan_LOC_matpc.22147.jpg, markup added by Matt Dawson, public domain.

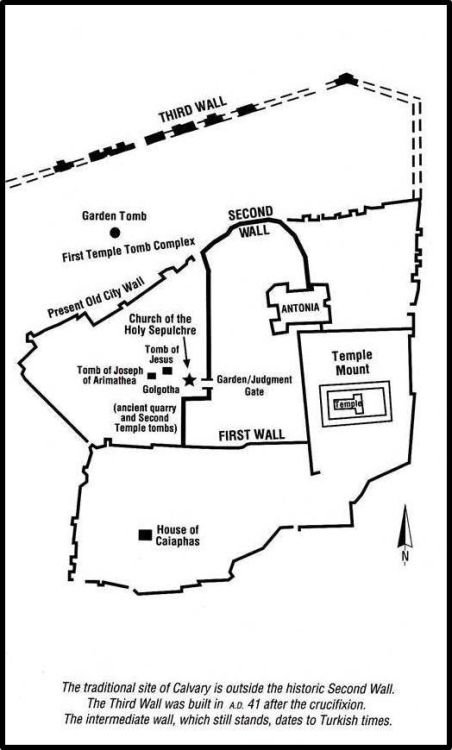

Josephus (1987, 703)16 states that “the city of Jerusalem was fortified with three walls, on such parts as were not encompassed with unpassable valleys; for in such places it had but one wall.” These walls must have been on the north side of Jerusalem because the Kidron and Hinnom valleys enclose the other sides (Kenyon 1974, 231). The third wall was begun by Herod Agrippa I who ruled from AD 41 to 44, but he stopped after only laying the foundation because he feared Claudius Caesar would “suspect that so strong a wall was built in order to make some innovation in public affairs,” or to revolt (Josephus 1987, 704).17 Therefore, the third wall did not exist when Christ was crucified. And since the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is located outside of both the first and second walls, it satisfies the biblical criteria that Christ was crucified and buried outside of the walls (John 19:20; Hebrews 13:11–12) (see fig. 25).

Fig. 25. The Walls of Jerusalem. Image taken from Price (1997, 312). Photo courtesy of Dr. J. Randall Price and Harvest House Publishers.

In the previous two sections, it was shown that the location upon which the Holy Sepulchre is built was transformed into a cemetery by the first century BC. Mare (1974, 37) explains that the “tombs [within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre] also argue for the area at that time being outside the city walls—certainly a cemetery would not be located within the city walls.” It is well known within the archaeology of Israel that when a Jewish city like Jerusalem expands, all known cemeteries and tombs are cleared for kosher reasons. Therefore, tombs that are excavated in Jerusalem after the city expanded are found empty.

Beside a Main Road

Foreman (2016, 505) explicates that “Matthew 27:39 and Mark 15:29 relate Jesus was scorned by those who ‘passed by’ when they saw him hanging on the cross. This implies Jesus was crucified near a road, in a visible location.” Hebrews 13:12 suggests the crucifixion took place near the city gate (506). This biblical description of Jesus being crucified by a main road is corroborated by the practice of crucifixion in antiquity. Quintilian (ca. AD 35–90s) made the following statement in Declamationes: “Whenever we crucify the guilty, the most crowded roads are chosen, where the most people can see and be moved by this fear. For penalties relate not so much to retribution as to their exemplary effect” (274; quoted in Hengel 1977, 50n14).

Bahat (1986, 38) points out that “the Gospels [also] tell us that Jesus was buried ‘near the city’ (John 19:20); the site we are considering was then just outside the city, the city wall being only about 500 feet to the south and 350 feet to the east.” The Holy Sepulchre’s close proximity to the major walls of the city strengthens the probability that it was close to a major road, for major roads (both internal and external) would enter and exit the city through gates in the walls. Simon of Cyrene was forced to carry Jesus’s cross as he was “coming in from the country” (Mark 15:21; Luke 23:25).

As stated earlier, Josephus (1987, 704)18 records that three northern walls surrounded Jerusalem. Although no archaeological remains of the second wall have been discovered (Serr and Vieweger 2016), Josephus (1987, 704)19 describes it: “The second wall took its beginning from that gate which they called ‘Gennath,’ which belonged to the first wall; it only encompassed the northern quarter of the city, and reached as far as the tower Antonia.” Between 1975 and 1978, Avigad (1980, 68–69) discovered what he believes is the Gennath Gate, thus the juncture of the first and second walls. If Avigad’s identification is correct, then “the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was just outside of the gate in Jesus’ day . . . Interestingly, ‘Gennath’ means garden and accords well with John’s detail that there was a garden in the place where Jesus was crucified (John 19:41)” (Foreman 2016, 515; Ritmeyer and Ritmeyer 2015, 37).

Concluding Remarks

Although it cannot be proven beyond doubt from archaeology, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre appears to be the authentic site of the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. First, tradition supports its authenticity. Bahat (1986, 37) shows why tradition is unusually compelling in this particular case:

As we have seen, the site was a turn-of-the-era cemetery. The cemetery, including Jesus’ tomb, had itself been buried for nearly 300 years. The fact that it had indeed been a cemetery, and that this memory of Jesus’ tomb survived despite Hadrian’s burial of it with his enclosure fill, speaks to the authenticity of the site. Moreover, the fact that the Christian community in Jerusalem was never dispersed during this period, and that its succession of bishops was never interrupted supports the accuracy of the preserved memory that Jesus had been crucified and buried here.

Second, Hadrian intentionally targeted and desecrated the most holy sites of the Jews and Christians in reaction to the Bar Kokhba revolt (AD 132–35):

When the Emperor Hadrian had defeated the Jews after the Bar Kokhba revolt (AD 132–135) and banished them from Jerusalem, in his attempt to replace Judaism and Christianity he built a temple to Venus over the site where the Church of the Holy Sepulchre now stands, a temple to Jupiter over where the Temple once stood, and a shrine to the god Adonis at the location of the Church of the Nativity [location of Jesus’ birth]. This was a standard practice to emphasize the triumph of one religion over another in the ancient world (a practice that has continued in Islam through the centuries). (Holden and Geisler 2013, 316–17)

If the Church of the Holy Sepulchre were not specially revered by the early Christians and Jews, then it would not have merited such a unique attack by Emperor Hadrian. Hadrian not only built a temple over the sites of the death, burial, and resurrection of Christ, but he also made this pagan temple the center of his new city Colonia Aelia Capitolina (Corbo 1992, 1072; Kramer 2020, 103–119). Also, Constantine later destroyed this pagan temple to Venus specifically because it was esteemed by all to stand upon the authentic location of the tomb of Jesus. It must be noted that he gave the orders to destroy the shrine before he had any confirmation that the tomb even existed. It was only the continuous tradition of the Jews and early Christians (who had not seen the tomb for hundreds of years due to the pagan shrine, as noted above) by which Constantine could act. After unearthing the tomb, he then gave instructions to build the most beautiful church in the world to commemorate the holy site. Constantine would not have taken such drastic measures if he were not convinced of the tomb’s authenticity.

Third, the fact that the location of the Holy Sepulchre was used as a limestone quarry until the beginning of the first century BC is strong evidence that it was outside of the city walls. The evidence of the location becoming a large cemetery at the beginning of the first century BC also demonstrates that it was outside of the city walls, just as Scripture states.

Fourth, the location of the Holy Sepulchre was not only a Second-Temple cemetery, but it was also a garden, was right outside the city walls by the Gennath Gate (meaning “garden”), and was by a main road—a must of ancient sites of crucifixion. All these archaeological details perfectly satisfy the biblical criteria for the location of the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus.

Considering all of the evidence, Kramer (2020, 111) makes the following conclusion concerning the Church of the Holy Sepulchre:

The authenticity of Golgotha and Jesus’ tomb . . . can be verified by layers of archaeological remains, one thing on top of another, and through credible historical sources that describe what happened there. Both the archaeological evidence and the historical evidence originate from multiple periods, covering the span of time from the original sacred events in the first century AD to the present.

The evidence available to us to authenticate these two sacred sites is overwhelming. We can be sure that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, standing today in the Old City of Jerusalem, marks the place where Jesus died and where He rose again.

Significance

As Habermas cogently argues, Christianity, which was centered and birthed in Jerusalem, could not have survived if Jesus had not risen from the dead. Because Christianity was birthed in Jerusalem, early skeptics and converts could go personally to the tomb to verify or disprove the resurrection. According to the facts presented above, the location of the Holy Sepulchre is where these early Christians would have come. The empty tomb was undoubtedly essential in the rapid explosion of Christianity in the first century. An empty tomb cannot be ignored or lightly dismissed by the skeptics. Habermas (1976) exhaustively refutes all the secular explanations for the empty tomb in his groundbreaking and still-foundational PhD dissertation, “The Resurrection of Jesus: A Rational Inquiry.”20 Gromacki (2002, 70–74) also gives an excellent overview and refutation of the common excuses used by skeptics to explain away the empty tomb. The location of the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus now commemorated by Church of the Holy Sepulchre was so specially revered by Christians and so sacrilegiously desecrated by the godless because Jesus rose from the dead and left an empty tomb behind at this site (see figs. 26 and 27 for a cross-section and floor plan of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre).

Fig. 26. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—cross-section. This figure positions Golgotha as it is currently located within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, rather than according to the older tradition that would place Golgotha directly beneath the smaller apse. However, this image is still useful for visualizing other details. Also, Golgotha’s Rock in this image would only need to be moved slightly to the right to visually represent the older tradition. Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/larrywkoester/37262985992/in/album-72157689253203885/, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 27. Church of the Holy Sepulchre—simplified floor plan. Larry Koester, https://www.flickr.com/photos/larrywkoester/36622544413/in/album-72157689253203885/, CC BY 2.0.

The Garden Tomb

The only competitor to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is the Garden Tomb (figs. 28–33). The Garden Tomb was identified by General Charles George Gordon, “the military hero of his day,” as the tomb of Jesus in 1883. Gordon also made much of the famed “Skull Hill” to persuade people of the authenticity of the Garden Tomb (see figs. 34 and 35). Because it is purported to be the tomb of Christ, the Garden Tomb “is one of Jerusalem’s best-known sites” (Barkay 1986, 42), receiving roughly 460,000 visitors in 2019 (Calvert 2019).

Fig. 28. Garden Tomb—street sign. Photo taken by Noam Chen for the Israeli Ministry of Tourism, https://www.flickr.com/photos/99743724@N08/14648312141, CC BY-ND 2.0.

Fig. 29. Garden Tomb—entrance to complex. State of Israel, https://www.flickr.com/photos/86083886@N02/34199137312/in/album-72157683232452995/, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 30. Garden Tomb—garden. The Garden Tomb is out of sight on the left, down the stairs. State of Israel, https://www.flickr.com/photos/86083886@N02/34199144122/in/album-72157683232452995/, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 31. Garden Tomb—entrance with small window on right (far). Gary Todd, https://www.flickr.com/photos/101561334@N08/43300924231, CC0 1.0, public domain.

Fig. 32. Garden Tomb—entrance (near). SeetheHolyland.net, https://www.flickr.com/photos/seetheholyland/4163586777/in/album-72157622949194634/, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Fig. 33. Garden Tomb—Resurrection monument. atora999, public domain.

Fig. 34. Garden Tomb complex—Skull Hill. Gary Todd, https://www.flickr.com/photos/101561334@N08/42582652524/in/album-72157698086750964/, CC0 1.0, public domain.

Fig. 35. Garden Tomb complex—Skull Hill. Derek Winterburn, https://www.flickr.com/photos/dnwinterburn/8699190421/in/album-72157629056988243/, CC BY-ND 2.0.

The St. Étienne Tomb Complexes

Barkay strongly insists that the Garden tomb is an Iron Age tomb, “the time of the kings of Judah (eighth and seventh century BC).” One reason is that “the Garden Tomb was probably part of the same cemetery as the St. Étienne (St. Stephen) tomb complexes. It lies only a few feet from Cave Complex Number 1 at St. Étienne and is hewn into the very same cliff” (Barkay 1986, 50). Barkay and Kloner (1986) have written in detail as to why they identify the St. Étienne tomb complexes as belonging to the First Temple period. One eighth/seventh-century feature of these caves is the following:

Inside the doorway to the entrance chamber is a step that forms an additional threshold. In this rock-hewn step there are carved two three-quarter-circle sockets; these sockets originally held the hinges of a double door that controlled access to the burial cave. Steps like this one, with similar sockets, are known from various Iron Age II (eighth to seventh century BC) structures. (27)

Some other eighth and seventh century features of the burial caves at the St. Étienne tomb complexes are (1) decorative, rectangular stone recesses carved into the walls which mimicked cedar-paneling decoration; (2) decorative cornices decorating the top of the walls; (3) the “carefully dressed, smooth surfaces” on the walls which lack the evidence of tooling, chiseling, and claws used in preparing the walls of Second Temple period tombs; (4) multiple rooms or burial chambers leading off a central entrance chamber; (5) burial benches on the three walls of the burial chamber (excluding the wall with the entrance thereby forming a u-shape) to lay the deceased instead of the Second Temple kokhim and arcosolia; (6) headrests to hold the deceased heads are carved into the burial benches; and (7) repositories cut beneath one of the side burial benches of each burial chamber where “the bones and burial gifts of the earlier generation were simply scooped up from the burial benches and placed in the repository under the bench” (Barkay and Kloner 1986, 27–38).

The Garden Tomb Characteristics

Now that the details of the St. Étienne tomb complexes have been discussed, a closer examination of the Garden Tomb itself will be undertaken. Barkay (1986, 51–52) gives the following argument against dating the Garden Tomb to the time of Christ:

Not a single tomb from Second Temple times has been found in this area. Just as we now know much more about Iron Age tombs, we also know more about tombs from the Second Temple period. Jesus lived in the late Second Temple period; the Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 A.D. A great number of burial caves from the Second Temple period have been discovered in other areas of Jerusalem, but not one in the area surrounding the Garden Tomb. By the Second Temple period, Jerusalemites had located their cemeteries further north. The southernmost burial cave of the Second Temple period is the luxurious “Tombs of the Kings,” about 1,970 feet (600 m) north of the Garden Tomb.

Also, the “basic arrangement of the rooms or chambers” of the Garden Tomb does not correlate well with tombs of the Second Temple period. Two-chamber burial tombs of the Second Temple period normally have “the inner chamber [cut] behind the entrance chamber, further under the rock,” but “the Garden Tomb cave consists of two adjoining chambers, one beside the other” (Barkay 1986, 52) (see fig. 36). As already stated, Second-Temple burial caves typically utilize kokhim or arcosolia, but the Garden Tomb features the prominent burial benches of the First Temple period (53) (see figs. 37–39). Second Temple burial rooms would have a square “pit” or sunken floor dug into the center of the room with benches carved around the perimeter of the pit on all sides except the entrance side. The pit “allowed ancient workmen to stand erect in the low-ceilinged cave” (Kloner 1999, 24). Bodies would presumably be laid on the bench while they were prepared for burial. After preparation, they would be placed into one of the kokhim dug into the perimeter walls (Price and House 2017, 260). The Garden Tomb does not have this structural design either (Barkay 1986, 53–55). Lastly, Barkay (53–55) points to the lack of markings on the walls of the Garden Tomb, the same markings that were missing in the Iron-Age St. Étienne tomb complexes:

Fig. 36. Garden Tomb—schematic placed at the Garden Tomb in 2007. James Emery, https://www.flickr.com/photos/emeryjl/498291604/in/album-72157600258422892/, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 37. Garden Tomb—Interior. Deror_avi, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24799708, CC BY-SA 2.5.

Fig. 38. Garden Tomb—burial chamber. Derek Winterburn, https://www.flickr.com/photos/dnwinterburn/8699194539/in/album-72157629056988243/, CC BY-ND 2.0.

Fig. 39. Garden Tomb—Interior of burial chamber. Photo of the interior of the Garden Tomb taken between 1934 and 1939 showing the “weeping chamber” and stairs leading into the burial chamber. Public domain.

Another telltale sign of Second Temple tombs is evidence of the use of a so-called comb chisel, which had a toothed edge. This kind of chisel left marks that look like small parallel lines, called combing, on the rock surfaces. The Garden Tomb cave, however, contains no sign of comb chiseling. Thus, dating this cave to the Hasmonean or Herodian period (first century BC-first century AD) seems completely out of the question.

Concluding Remarks

As demonstrated above, the Garden Tomb is a First-Temple period, Iron-Age tomb. Therefore, the Garden Tomb cannot be the authentic tomb of Christ because John 19:41 explicitly states that Jesus was buried in “a new tomb in which no one had yet been laid.” This description obviously would not be true of a tomb that had been in use since the eighth to seventh century BC. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is a much better candidate for Jesus’s tomb.

A Rolling Stone

The Bible states in all of the gospels except John that the stone sealing Jesus’s tomb was “rolled” (Matthew 27:60, 28:2; Mark 16:2–4; Luke 24:2). John does not say that the stone was rolled, but merely that it was “removed” or “taken away” (John 20:1). Archaeology reveals that “in Jesus’ time, round blocking stones were extremely rare and appeared only in the tombs of the wealthiest Jews” (Kloner 1999, 28). Most stones that were used to seal tombs were square:

It is true that the massive blocking stones (in Hebrew, golalim; singular, golel or golal) used to protect the entrances to tombs in Jesus’ day came in two shapes: round and square. But more than 98 percent of the Jewish tombs from this period, called the Second Temple period (c. first century B.C.E. to 70 C.E.), were closed with square blocking stones. Of the more than 900 burial caves from the Second Temple period found in and around Jerusalem,21 only four are known to have used round (disk-shaped) blocking stones. (23; emphasis added)

Price describes these square sealing stones as being “shaped something like a bolt with one end designed to provide a close fit for the small opening forming the doorway of the tomb. The larger remainder of the stone had a flange so it would rest against the outside surface of the tomb” (Price and House 2017, 259–260).

The Bible states that Jesus was buried in the personal tomb of Joseph of Arimathea (Matthew 27:57–61). Joseph’s role in Christ’s burial is also mentioned in Mark 15:42–47, Luke 23:50–56, and John 19:38–42. The fact that tombs with round sealing stones were extremely rare and could only be afforded by the richest of society perfectly matches the description of Joseph of Arimathea in the Scriptures:

The Gospels portray him as a “rich man” (Matt 27:57), a “prominent member” of the Sanhedrin (Mark 15:43), and a man with significant status to be granted a private audience with Pontius Pilate and then given special permission to bury the body of a condemned criminal (not a relation) whose high-profile case had been controversial (John 19:38) . . . . This description of an elite in Jerusalem society argues for someone whose family tomb could have fit the category of a rolling-stone tomb. (Price and House 2017, 260– 261; see figs. 40 and 41 for examples of tombs with round sealing stones)

Fig. 40. Second-Temple period tomb in Jerusalem purported to be Herod’s family tomb. Derek Winterburn, https://www.flickr.com/photos/dnwinterburn/9037162286/in/album-72157629056988243/, CC BY-ND 2.0.

Fig. 41. Authentic Jewish tomb dating from the first century AD. The kincaidibles, https://www.flickr.com/photos/kincaidibles/49409697753/in/photolist-2ihd4LD-2ihd4XR-2ihaBJz-9QPbib-2ihe5fi-2ihe1Kc-2ihd1XCW61rLT-2ihcYrv-2ihe75f-5HMRtL-9rXVj8-9dsPvLh2K2zj-7kDMf3-by9S1i-6jM6iS, CC BY 2.0.

The Bible also describes Joseph’s tomb as being “cut out of the rock” (Matthew 27:60; Luke 22:53). Rock-cut tombs being exclusively for the wealthy is also confirmed by archaeology: “For the poorer lower class a cave was utilized for burial because a rock-cut tomb was too expensive. Joseph of Arimathea was able to afford the most expensive of tombs, the kind used by the upper class and nobility” (Price and House 2017, 261).

Due to the rarity of rolling-stone tombs in Jesus’s time, it is argued that Jesus’s tomb must have had a square sealing stone (Kloner 1999; Sauter 2020). Another argument is that the Gospels’ statements concerning the blocking stone of Jesus’s tomb being rolled are irrelevant because even square sealing stones were rolled when they were moved (Sauter 2020; von Wahlde 2015). However, this argument ignores details in the biblical text. Mark 16:3 reveals the discussion Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome were having while they were on their way to Jesus’s tomb: “And they were saying to one another, ‘Who will roll away the stone for us from the entrance of the tomb?’” These three women were not interested in moving Jesus’s sepulcher sealing stone to another location. They were only interested in gaining entrance into the tomb so that they “might go and anoint him” (Mark 16:1). By the time the closefitting “stopper” of the cork-shaped square sealing stone was dislodged enough from the entrance to roll it, the women would most likely have been able to enter the tomb to anoint Jesus’s body. Therefore, von Wahlde’s (2015, 74) following statement is irrelevant: “It may very well be that people rolled the ‘corkshaped’ stones away from the tomb. Once you see the size of a ‘stopper’ stone, it is easy to see that, however one gets the stone out of the doorway, chances are you are going to roll it the rest of the way.” Likewise, Sauter’s (2020) argument is also irrelevant: “Although they certainly would not have rolled as easily as round (disk-shaped) stones, cork-shaped stones still could have been rolled.” Proving that square blocking stones “could have been rolled” is not enough to satisfy all the details given in the biblical account.22

The significance of this section is that it confirms key biblical details of the resurrection account in Scripture. The Gospels state that Jesus was buried and resurrected within a tomb hewn out of rock or stone (Matthew 27:60; Mark 15:46; Luke 23:53). The Scriptures state that the “great stone” that was rolled across the entrance of Jesus’s tomb to seal it (Matthew 27:60; Mark 15:46, 16:4) was later rolled away by an angel at the time of the resurrection (Matthew 28:2; Mark 16:4; Luke 24:2; John 20:1). These details are prominent in the resurrection account. However, archaeology reveals that rock-hewn, rolling-stone tombs in early-first-century Jerusalem could only be afforded by the most affluent of society. It is the rich man named Joseph of Arimathea (Matthew 27:57–60; Isaiah 53:9) who allows for these details of Jesus’s resurrection to be a historical reality. In other words, Scripture gives details about the tomb of Jesus from which He resurrected. It also states that He was buried in the personal tomb of a rich and affluent member of society. Archaeology reveals that the details in the Gospels perfectly describe the kind of tomb in which the most-wealthy of first-century Jerusalem would have been buried.

Jehoḥanan son of ḤGQWL

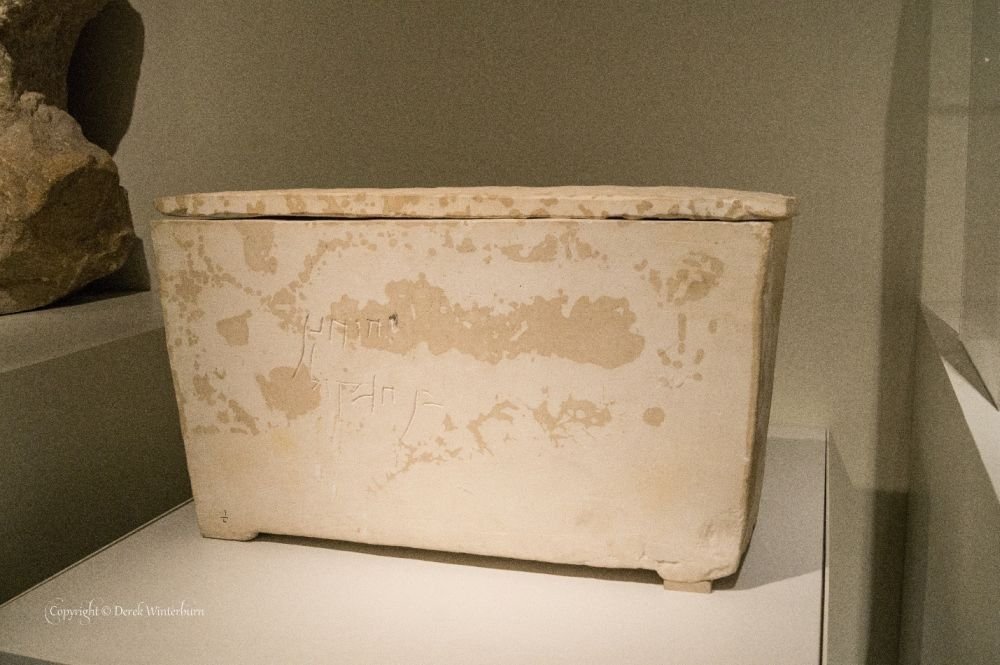

In 1968, Tzaferis (1970, 18) excavated four Jewish tombs in and around Giv’at ha-Mivtar, a suburb of Jerusalem. The pottery in the tombs dates them between “the Late Hellenistic period (end of second century BC) and the destruction of the Second Temple (A.D. 70)” (20). Tomb I had twelve burial kokhim or loculi (Latin) and eight ossuaries (18, 28). Ossuary No. 4 is of particular interest (see fig. 42). Tzaferis gives the following description of this ossuary: “0.57 × 0.34 m. Undecorated; flat lid; on one long side are two Aramaic inscriptions: (a) Yhwḥnn ; (b) Yhwḥnn bn ḥgqwl . Contained the bones of an adult male and a child” (28).23 Joseph Naveh, who was tasked with “the deciphering of the inscriptions and their publication,” translates these two descriptions as “Jehoḥanan ,” and “Jehoḥanan son of ḤGQWL ” (respectively). Naveh found no satisfactory translation for ḤGQWL , but he does speculate it may be a corrupted form of Ezekiel (1970, 33–37).

Fig. 42. Ossuary of Jehoḥanan . Derek Winterburn, https://www.flickr.com/photos/dnwinterburn/8566636212/in/album-72157629056988243/, CC BY-ND 2.0.

Tzaferis (1970, 31) explains why the skeleton of Jehoḥanan son of ḤGQWL in Ossuary No. 4 is so unique:

Ossuary No. 4 (tomb I) is a most interesting case: the lowest parts of the calf bones (tibiae and fibulae) of one individual had been broken24 and the heel bones (calcanei) pierced by an iron nail. This is undoubtedly a case of crucifixion . . . . Mass crucifixions in Judea are mentioned under Alexander Janneus, during the revolt against the census of A.D. 7, and again during the Jewish revolt which brought about the final destruction of the Second Temple in A.D. 70. Individuals were also crucified occasionally by the Roman procurators.

Since the pottery and ossuaries found in tomb I exclude the period of Alexander Janneus for this crucifixion, and since the general situation during the revolt of A.D. 70 excludes the possibility of burial in tomb I, it would seem that the present instance was either of a rebel put to death at the time of the census revolt in A.D. 7 or the victim of some occasional crucifixion. It is possible, therefore, to place this crucifixion between the start of the first century A.D. and somewhere just before the outbreak of the first Jewish revolt.

Yet another striking piece of evidence is provided by finds in the same tomb. The Aramaic inscription found on ossuary No. 1 mentions a certain Simon, who is called ‘builder of the Temple’ . . . . The Temple mentioned here is certainly the Temple built by Herod and his successors, and it is clear that this Simon died sometime after the building of the Temple had commenced, i.e. after 20 B.C. The building of the Temple was not finished until a short time before its destruction in A.D. 70, and it is within this period that the death of Simon must be dated.

Professor Nico Haas of the department of anatomy at Hebrew University of Jerusalem Hadassah Medical School was the medical expert who examined the bones (Haas 1970, 38–59). Jehoḥanan son of ḤGQWL was 24 to 28 years old (42). A large iron nail still remained in the right calcaneum (heel bone) of the victim (see fig. 43). Apparently, the nail was too difficult to remove without severely damaging the body, so the victim was buried with the nail still in his heel. Beneath the head of the nail, was a “relatively large (1.5– 2 cm) wooden plaque,” which was probably used to help keep the heel pinned to the cross, preventing the nail from pulling through the foot (55–56). The wood of the plaque was determined to be olive wood; while, the wood on the tip of the nail was not able to be identified with certainty (Zias and Sekeles 1985, 24).25 The tip of the nail was bent over, apparently from hitting a knot. Haas believed that the iron nail pierced both heel bones, but this was later shown to be incorrect:

Fig. 43. Calcaneus (heel bone) of Jehoḥanan . Derek Winterburn, https://www.flickr.com/photos/dnwinterburn/8565537673/in/album-72157633021056870/, CC BY-ND 2.0.

Haas’s assertion that a wooden plaque and the right and left heel bones were penetrated by a single nail was in our opinion anatomically incorrect and based on the misidentification of a left calcaneum. Furthermore, since the total length of the nail from head to tip was 11.5 cm. [4.5 inches] and not 17–18 cm. as Haas assumed, there simply was not enough room for both heel bones and a 2 cm. wooden plaque to have been pierced by the nail and affixed to the vertical shaft of the cross. (23)

From the skeletal remains, the position of the crucified man can be assumed: “Regarding the positioning of the lower limbs and their relation to the upright, the evidence suggests that the most logical reconstruction would have the condemned straddling the upright with each foot nailed laterally to the cross” (Zias and Sekeles 1985, 26). This position of the man straddling the cross with a nail going through the heels and into the sides of the upright matches the depiction of crucifixion shown in the third-century AD Alexamenos graffito.

Although it was common practice to leave crucified victims on the cross post-mortem for days to be eaten by birds and beasts or to merely throw their bodies into large pits unburied,26 Jehoḥanan son of ḤGQWL proves that there were exceptions and that crucified victims did sometimes receive burials. Josephus (1987, 679)27 also testifies to crucified victims being buried: “The Jews used to take so much care of the burial of men, that they took down those that were condemned and crucified, and buried them before the going down of the sun.” Evans (2005, 234–39) shows that Jews prioritized burial for two reasons: (1) out of respect and honor for the dead and (2) “to avoid defilement of the land of Israel,” as required by the Mosaic Law (Deuteronomy 21:22–23; see also Ezekiel 39:14, 16). Evans (233) argues that it is highly unlikely that Jesus was not buried: Only in times of rebellion—when Roman authorities did not honour Jewish sensitivities—were bodies not taken down from crosses or gibbets and given proper burial. It is highly improbable, therefore, that the bodies of Jesus and the other two men crucified with him would have been left unburied overnight, on the eve of a major Jewish holiday, just outside the walls of Jerusalem.

The famous Roman Digesta is another ancient source that confirms that even those who received capital punishment were to be permitted proper burials: “The bodies of executed persons are to be granted to any who seek them for burial” (Watson 1998, 4:377).28 The Digesta gives further details concerning the bodies of those who suffered capital punishment:

The bodies of those who suffer capital punishment are not to be refused to their relatives; and the deified Augustus writes in the tenth book of his Vita Sua that he also had observed this [custom]. Today, however, the bodies of those who are executed are not buried otherwise than if this had been sought and granted. But sometimes it is not allowed, particularly [with the bodies] of those condemned for treason. The bodies of those condemned to be burned can also be sought so that the bones and ashes can be collected and handed over for burial.29 (Watson 1998, 4:377; brackets in original)

As the Digesta states, treason would be one of the occasions upon which the dead would be refused burial (see Evans above). Jesus was not considered by the Romans to be guilty of treason. Pilate and Herod found no fault in Jesus (Matthew 27:23–24; Mark 15:14; Luke 23:4, 14–16, 22; John 18:38). Also, the Digesta specifies that permission was sometimes necessary to bury the dead. The gospels document that Joseph of Arimathea requested and received permission from Pilate to bury Jesus (Matthew 27:57–58; Mark 15:42–45; Luke 23:50–53; John 19:38).

Especially noteworthy is that the edict above (Dig. 48.24.1) specifically names Emperor Augustus (reigned 27 BC–AD 14) as allowing criminals who received capital punishment to be buried. Augustus was the Roman Emperor before the death of Jesus took place (Tiberius was the emperor when Jesus was crucified). Because the edict was in place from the time of Augustus until it was included in Emperor Justinian I’s Digest in the 6th century AD and beyond, it would have been in place during the time of Jesus’s death also.

The discovery of the ossuary and skeleton of Jehoḥanan son of ḤGQWL is greatly significant because it proves conclusively that victims of crucifixion were sometimes buried. In the case of Jehoḥanan son of ḤGQWL , he received a privileged burial: “ossuaries were an expensive luxury, and . . . not every Jewish family could afford them” (Tzaferis 1970, 30). Also significant is that Jehoḥanan son of ḤGQWL was crucified during the same timespan as Jesus. This archaeological discovery provides plausibility for the biblical description of Christ’s resurrection. The biblical description of the resurrection obviously could not be accurate if Jesus were never buried. If Jesus were left on the cross for days after His death to be eaten by wild animals, or, if He were thrown into a large pit with other common criminals, then the biblical account of the resurrection would immediately be false. The account of Jesus’s resurrection in Scripture necessitates that He first received a proper burial. The historical and archaeological evidence demonstrates that Jesus would have been allowed to be buried. Therefore, the argument that the account of Jesus’s resurrection in the gospels must be untrue because victims of crucifixion would have been denied burial is factually inaccurate.

The Alexamenos Graffito

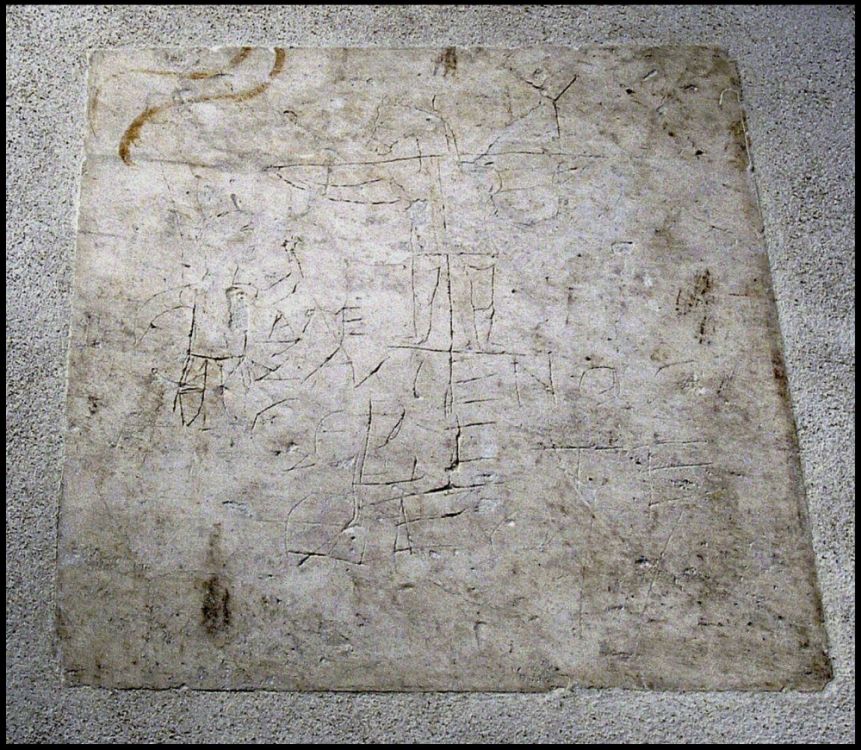

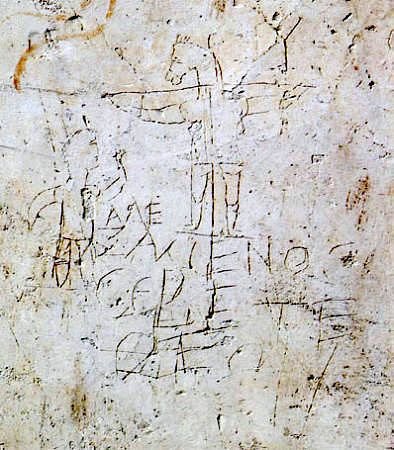

In 1857, some graffiti was found on Palatine Hill in Rome. This graffiti has come to be known as “The Alexamenos Graffito.” Hare (1882, 208) gives a description of this archaeological find:

Beyond this a number of chambers have been discovered under the steep bank of the Palatine, and retain a quantity of graffitæ scratched upon their walls. The most interesting of these, found in the fourth chamber, has been removed to the museum of the Collegio Romano. It is generally believed to have been executed during the reign of Septimius Severus [reigned 193–211], and to have been done in an idle moment by one of the soldiers occupying these rooms, supposed to have been used as guard-chambers under that emperor. If so, it is perhaps the earliest existing pictorial allusion to the manner of our Saviour’s death. It is a caricature evidently executed in ridicule of a Christian fellow-soldier. The figure on the cross has an ass’s head, and by the worshipping figure is inscribed in Greek characters, Alexamenos worships his God. These chambers acquire a great additional interest from the belief which many entertain that they are those once occupied by the Prætorian Guard, in which St Paul was confined.30

As Hare describes, the image is of a person named Alexamenos standing before a cross with one arm raised (apparently in an act of worship or prayer). On the cross, is a figure being crucified with a human’s body and a donkey’s head (see figs. 44 and 45).

Fig. 44. Alexamenos Graffito. The Alexamenos Graffito is in the Palatine Antiquarium Museum in Rome. This image is in the public domain.

Fig. 45. The Alexamenos Graffito. This image is in the public domain.

The early Latin apologist Tertullian (ca. AD 196–c. 212) writes about how pagans mocked the Christians’ God: “For, like some others, you are under the delusion that our god is an ass’s head” (Tertullian 1885b, 30).31 A certain Jew in Tertullian’s time even carried around a caricature to mock Christians: “But lately a new edition of our god has been given to the world in that great city: it originated with a certain vile man who was wont to hire himself out to cheat the wild beasts [fought beasts for money, which resulted in his skin being flayed], and who exhibited a picture with this inscription: The God of the Christians, born of an ass. He had the ears of an ass, was hoofed in one foot, carried a book [most likely the Scriptures], and wore a toga” (31).32

Holden and Geisler (2013, 309) point out the significance of Alexamenos graffito:

This graffito is an important attestation to the fact that early Christians worshipped Jesus as God, were the targets of slander and ridicule, and used the crucifix in their worship, at least by the third century. This latter, crucial aspect supports the Gospel statements describing crucifixion as the manner by which Christ died, a method of capital punishment that has been previously disputed.

What especially is pertinent to this paper is the fact that archaeology confirms Jesus was worshipped as God at least as early as the third century. This deification of Jesus indirectly provides support for the resurrection. If Jesus had not risen from the grave, He would not have been worshipped as God. Jesus explicitly and repeatedly predicted that He would rise from the dead (e.g., Matthew 12:40, 16:21, 20:18–19, 24:6–7; Mark 10:32–34; Luke 18:31–33; John 2:19). Jesus so clearly taught that he would be raised from the dead on the third day that the chief priests and Pharisees went to Pilate and said

“Sir, we remember how that impostor said, while he was still alive, ‘After three days I will rise.’ Therefore order the tomb to be made secure until the third day, lest his disciples go and steal him away and tell the people, ‘He has risen from the dead,’ and the last fraud will be worse than the first.” Pilate said to them, “You have a guard of soldiers. Go, make it as secure as you can.” So they went and made the tomb secure by sealing the stone and setting a guard. (Matthew 27:62)

Therefore, if Jesus had not risen from the dead, then He would have been seen as a powerless liar and fraud. Paul also states that if Christ were not risen from the dead, then the faith of Christians “is in vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14). The mockery of the Alexamenos graffito manifests the attitude Christians would have had toward Christ if the resurrection had not happened: “For outsiders Jesus has definitely been a failure as God’s representative and as messianic king. A messianic king on the cross who has failed, a healer who cannot save himself, a confidant of God whom God abandons, a divine man who does not embody strength and life is a laughable figure” (Luz 2005, 537). The beauty of the Alexamenos graffito is that a crude sketch on a wall intended to mock Christ and Christians has actually been used by God to bring glory and validity to Himself and His Son.

The Megiddo Mosaic Inscription

Like the Alexamenos graffito, the Megiddo Inscription provides indirect archaeological evidence for the resurrection of Christ (see figs. 46–48). Tepper and Segni (2006, 5) provide the contextual background for this find:

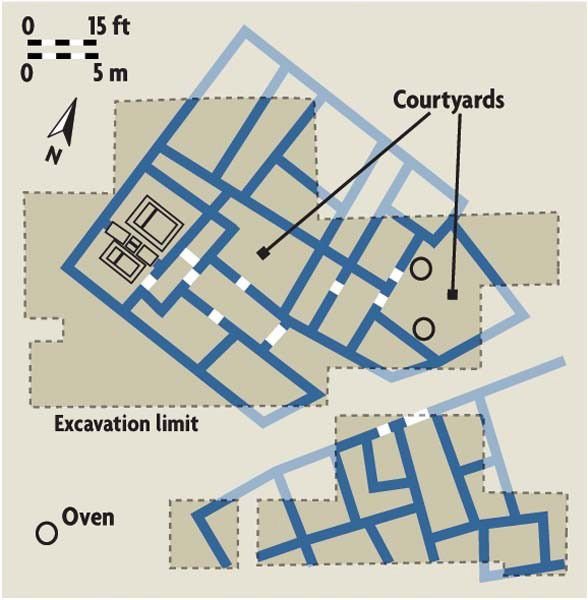

From 2003 to 2005 extensive archaeological salvage excavations were conducted inside the Megiddo Prison compound. The excavations, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), were carried out for the purpose of development, at the request and with the funding of the Israel Defense Forces and later the Israel Prison Service. An area of 3000 sq m (three dunams) was excavated inside the ancient Jewish village of Kefar ‘Othnay; its remains are dated by the various finds from the Early Roman to the late Byzantine periods. They demonstrate daily life in the rural settlement that developed and expanded alongside the Roman army camp.

A large residential building, dating to the third century CE, was exposed during the excavation of the settlement. Finds from this building indicate that it was used by soldiers of the Roman army and that one of its wings functioned as a prayer hall for a local Christian community. This discovery is of great importance as it dates to the period prior to the recognition of Christianity as an official religion.

Fig. 46. Megiddo prison from the top of Tel Megiddo. Golf Bravo, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zomet_megido1.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 47. Map of Megiddo complex. The Prayer Hall is the room containing the rectangles (the larger rectangles are the mosaic panels, and the two smaller rectangles in the center are thought to be the remains of the Eucharist table) in the southwest corner of the top structural complex. Image source is (Tzaferis 2007). Photo courtesy of Biblical Archaeology Society.

Fig. 48. The “Christian Prayer Hall” of the Megiddo Complex. The northern panel (the largest panel on the left) contains the Gaianus Inscription. The southern panel (the second-largest panel on the far right) contains the Women Inscription on the eastern side (top) and the Akeptous/Megiddo Inscription on the western side (bottom). The two fish facing opposite directions in the center of the northern panel is “a distinct Christian symbol for Christ.” The inscription along the northern edge of the panel honors Gaianus, the centurion who paid for the mosaics: “Gaianus, also called Porphyrius, centurion, our brother, has made the pavement at his own expense as an act of liberality. Brutius has carried out the work.” The Women Inscription of the southern panel “asks for remembrance of ‘Primilla and Cyriaca and Dorothea, and moreover also Chreste.’” Nothing more is known of these four women (Tzaferis 2007). Photo Niki Davidov, Courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Tepper and Segni therefore called this wing of the residential building a “Christian prayer hall” (5).

The “Christian prayer hall” was 5 × 10 m (16.4 × 32.8 ft) (Tepper and Segni 2006, 24). This hall has a podium in the center of the room with four separate panels of mosaics surrounding it (25). On top of the mosaics, pottery shards from the third century were discovered, thus dating the mosaics (26–27). Twenty-eight coins from the second to third century AD were also found in the prayer hall (28). The inscriptions on the mosaics also help confirm a date (34).

The southern panel mosaic is the one that contains the Megiddo Inscription/Akeptous Inscription (Tepper and Segni 2006, 31).33 The southern panel is described as thus:

The southern panel (1.78 × 2.96 m) [5.8 × 9.7 ft] is delimited by a black frame and guilloche pattern in tones ranging from red to white. In the middle of the panel is a carpet of rosettes forming a repeating pattern of intertwined circles. This panel bears two inward-facing inscriptions (the Akeptous Inscription and the Women Inscription . . .). They are flanked by pairs of arches made of black tessserae. (31)

The Akeptous Inscription reads as follows: “The god-loving Akeptous has offered the table to God Jesus Christ as a memorial” (Tepper and Segni 2006, 36). The phrase “God Jesus Christ” is over-lined (instead of underlined) for extra emphasis (Holden and Geisler 2013, 308; Tepper and Segni 2006, 36). Tzaferis (2007) gives further explication: “The name for Jesus Christ is abbreviated using only the first and last letters and is delineated as a sacred name by a line placed above it, a practice that was typical of a later period; this is the earliest known example of it.” Scholars agree that “the table donated by Akeptous most likely served for the celebration of the Eucharist.” It may have also served for ceremonial meals or agape meals (Tepper and Segni 2006, 40). The Megiddo Mosaic dates to the third century AD, making it a candidate for the oldest church yet to be discovered in the Holy Land (Holden and Geisler 2013, 308).

Tepper and Segni (2006, 54) explain the significance of the Megiddo Inscription:

The discovery of the Christian prayer hall at Kefar ‘Othnay constitutes archaeological evidence of considerable importance, attesting to a Christian presence in the Land of Israel prior to the reign of Constantine, in a period that until recently has been explored mainly through literary sources. Additionally, the study of the building confirms the existence in the third century CE of a Christian community of pagan rather than Jewish origin.

Just as with the Alexamenos graffito, the Megiddo Mosaic shows that Jesus was being worshipped as God by at least the third century AD. Again, Jesus would not have been worshipped as God if He were still dead and decaying in Jerusalem. Therefore, the Megiddo Inscription is another indirect archaeological evidence for the resurrection.

The Nazareth Inscription

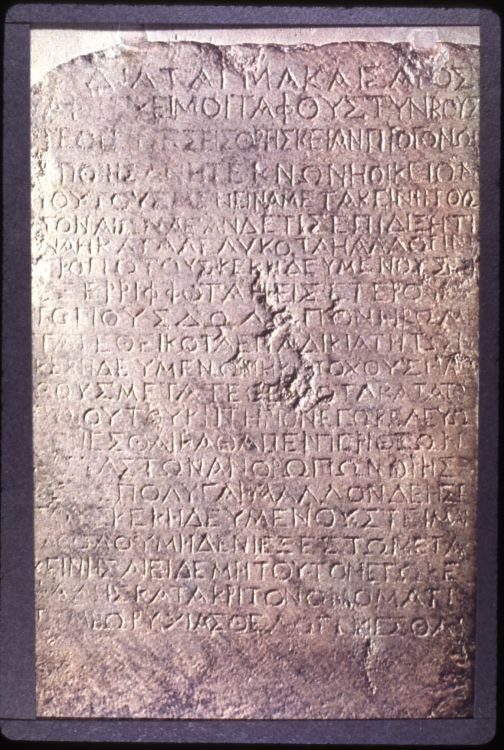

The Nazareth Inscription is one of the most important archaeological finds to support the resurrection of Jesus (see fig. 49). Although its purported connection to Jesus has come under attack in recent literature (Harper et al. 2020, 1–7), its significance cannot be dismissed.

Fig. 49. Nazareth Inscription. The Nazareth Inscription is currently held at the Louvre in Paris. Everett Ferguson, https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/ferguson_photos/2466/, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Background

The Nazareth Inscription contains 22 lines of Greek text and is “preserved on a plain marble slab measuring about 60 cm [23.62 in] high by 37.5 cm [14.76 in] wide” (Metzger 1980, 75). The Nazareth Inscription was purchased by Froehner, a private collector of ancient inscriptions and manuscripts, in 1878 (Billington 2020). Metzger (1980, 75–76) cautions readers not to assume too much of the Nazareth Inscription’s history:

Nothing is recorded of its previous history except a brief note in Froehner’s handwritten inventory: “Dalle de Marbre envoyée de Nazareth en 1878.” One should observe that the note does not say “discovered at Nazareth”, but “sent from Nazareth.” Whether the marble slab had been erected originally at Nazareth, or had been brought there from some other locality, either in antiquity or in modern times, is quite unknown. In the 1870’s Nazareth (like Jerusalem) was a natural market for dealers in antiquities.34

For more than 50 years, from 1878 to 1930, the Inscription “remained unknown to the scholarly world” (Billington 2020). Froehner’s collection was purchased in 1925 by the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris (Metzger 1980, 75). Here, it was “rediscovered and read by M. Rostovtzeff. Rostovtzeff told his friend, the French scholar M. Franz Cumont about this Inscription” (Billington 2020). Five years later in 1930, Cumont (1930, 241–266) brought the Nazareth Inscription to the attention of scholars when he published an article on the artifact.

Translation and Interpretation

Metzger, being one of the world’s premier authorities on the Greek language of antiquity, is more than qualified to give the interpretation of the Inscription. F. F. Bruce is another world-renown scholar of the Greek language. Clyde E. Billington (amongst others) has also translated the Nazareth Inscription and challenges some of the translational decisions of Metzger and Bruce. Since the following discussion will focus on the translations of these three scholars, a table has been created showing Metzger’s, Bruce’s, and Billington’s translations side-by-side (see table 1).

| Bruce Metzger37 | Clyde Billington38 | F. F. Bruce39 |

|---|---|---|

| EDICT OF CAESAR | Decree of Caesar | |

| It is my pleasure that | It is my decision [concerning] | It is my pleasure that |

| graves and tombs—whoever has | graves and tombs—whoever has | sepulchres and tombs, which have |

| made them as a pious | made them for the religious | been erected as solemn |

| service for ancestors or children | observances of parents, or children, | memorials of ancestors or children or |

| or members of their house— | or household members— | relatives, |

| that these remain unmolested | that these remain undisturbed | shall remain undisturbed |

| in perpetuity. But if any person lay | forever. But if anyone legally | in perpetuity. If it be shown |

| information that another either has | charges that another person has | that anyone has either |

| destroyed them, or has in any other | destroyed, or has in any manner | destroyed them or otherwise |

| way cast out the bodies which have | extracted those who have | thrown out the bodies which have |

| been buried there, or | been buried, or | been buried there or |

| with malicious deception has | has moved with wicked intent those | removed them with malicious intent |

| transferred them to other | who have been buried to other | to another place, thus committing a |

| places, to the dishonor of those | places, committing a crime against | crime against those |

| buried there, or has removed | them, or has moved | buried there, or removed |

| the headstones or other stones, | sepulcher-sealing stones, | the headstones or other stones, |

| in such a case I command that a | against such a person I order that a | I command that against such person |

| trial be instituted, | judicial tribunal be created, | the same sentence be passed in |

| protecting the pious services of | just as [is done] concerning | respect of solemn memorials of men |

| mortals, just as if they were | the gods in human religious | as is laid down |

| concerned with the gods. | observances, | in respect of the gods. |

| For beyond all else it shall be | even more so will it be | Much rather must one |

| obligatory to honor those who have | obligatory to treat with honor those | pay respect to those who |

| been buried. | who have been entombed. | are buried. |

| Let no one | You are absolutely not to allow | Let no one |

| remove them | anyone to move [those who have | disturb them |

| for any reason. | been entombed]. | on any account. |

| If anyone does so, however, it is my | But if [someone does], I wish that | Otherwise it is my will |

| will that he shall suffer capital | [violator] to suffer capital | that capital sentence be passed upon |

| punishment on the charge of tomb- | punishment under the title of tomb- | such person for the crime of tomb- |

| robbery. | breaker. | spoliation. |

First, Metzger and Bruce both attest that the Inscription was based upon a Latin original due to several instances in the Greek that seem to mirror common Latin phraseology (Bruce 1962, 319; Metzger 1980, 80). Metzger does not directly translate the first line of the Nazareth Inscription,35 which Billington (2020) translates as “EDICT OF CAESAR” and Bruce (1962, 319) translates as “Decree of Caesar.” Billington (2020) argues that this opening title “is almost certainly a rump or abridged version of an imperial rescript. A rescript was a letter of response sent by the emperor to an imperial official who had earlier written a letter to him about some problem.” Billington (2020) explains that “it was fairly common for imperial rescripts to be treated as legal edicts.” Of course, the “problem” that Billington believes was the subject of the rescript was the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Though Metzger (1980, 90) does not necessarily agree that the title is a rescript, he does assert that one can say with assurance that “the ordinance was promulgated after a particularly serious violation of sepulture.”