The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

Grand Canyon of Arizona is the best-known example of hydraulic erosion on planet earth. No other canyon has been so carefully scrutinized by geologists. Therefore, Grand Canyon is the most important landscape on planet earth to be explained by competing creationist and evolutionist paradigms. Four hypotheses have been proposed for the erosion of Grand Canyon: (1) drainage spillover, (2) antecedent river, (3) stream piracy, and (4) flood drainage. The first geologist ever to explore Grand Canyon, John Newberry, recognized in 1858 that it was carved through a highland arch that separated topographic basins. Newberry proposed drainage spillover of the elevated terrain by what has later been called ancient “Hopi Lake” (aka “Lake Bidahochi”). We trace the history of “spillover” and “breached dam” hypotheses from Newberry’s first discovery, but we focus on the last 50 years through both creationist and evolutionist thinking. Fifty years ago, when uniformitarian doctrine was stifling imaginative thinking about Grand Canyon erosion, Hopi Lake was “the lake that gets no respect,” and spillover was “the forgotten transverse drainage hypothesis.” Also, 50 years ago, three creationists (Henry M. Morris, Jr., Clifford Burdick, and Bernard Northrup) affirmed the creationist consensus that Grand Canyon was eroded by catastrophic spillover of a post- Flood lake. That recent erosion formed a young Colorado River. In 1988 Steve Austin and Ed Holroyd were working on the configuration of lakes east and north of Kaibab Upwarp. Bob Scarborough had surveyed lake sediments to understand better the western boundary of ancient Hopi Lake. Also, in 1988, Norm Meek had “rediscovered” Afton Canyon of the Mojave Desert in California that had been carved by spillover of ancient Lake Manix producing a one-tenth scale analog to Grand Canyon. By 1988, pieces of the larger spillover puzzle were being assembled. By the year 2000, Bob Scarborough, Norm Meek, Ron Dorn, Jon Spencer, Philip Pearthree, John Douglass, Kyle House and Todd Dallegge were developing these ideas within the evolutionist community. Also, by 2000, Andrew Snelling and Tom Vail were communicating these ideas within the creationist community. By 2012, the spillover explanation was called “a favored concept for two decades.” Responding to spillover’s popularity, a self-appointed panel of experts challenged the notion. “Afton Canyon Controversy” focused on a different model for Lake Manix with headward erosion of Afton Canyon. Fact rechecking by U.S. Geological Survey silenced critics in the “Afton Canyon Controversy” by 2014. The “Crooked Ridge Miocene River” called for a much different basin configuration without Hopi Lake against the Kaibab Upwarp. Spillover critics that promoted the “Crooked Ridge Miocene River” experienced an almost simultaneous “spirit of repentance” killing quickly the “Crooked Ridge River” in 2016. Since then, Lake Manix and Hopi Lake have been restored, silently, as viable spillover candidates. Why no fanfare? These lakes continue to receive distressing abuse from “the establishment,” verifying they are the lakes that get no respect. This spillover story shows how pervasive and deep-seated evolutionary assumptions are within the “Grand Debate.” Today, more than 20 earth scientists (most with Ph.D. degrees) have constructively affirmed spillover theory, at the same time, maintaining an attitude of respect, not contempt, toward the ancient lake in northeastern Arizona. Geologists have been searching for the “Miocene River” for 150 years. If it is found, it would be the primary alternate to the spillover hypothesis. We should remember an important fact—creationist and evolutionist thinking about spillover continues to make a significant contribution to our understanding of erosion of Grand Canyon.

Keywords: Colorado River, Grand Canyon, erosion, Kaibab Upwarp, East Kaibab monocline, transverse drainage, spillover model, overtopping, ponding and overflow, breached dam hypothesis, Hopi Lake, Lake Bidahochi, Crooked Ridge, Bidahochi Formation, Mount St. Helens, tufa, Lake Manix, Afton Canyon, Pliocene lake sedimentation, Miocene river sediments, tuff ring, maar, scoria cone, paleontology, tectonics, isostacy, framework of Scripture, geologic time

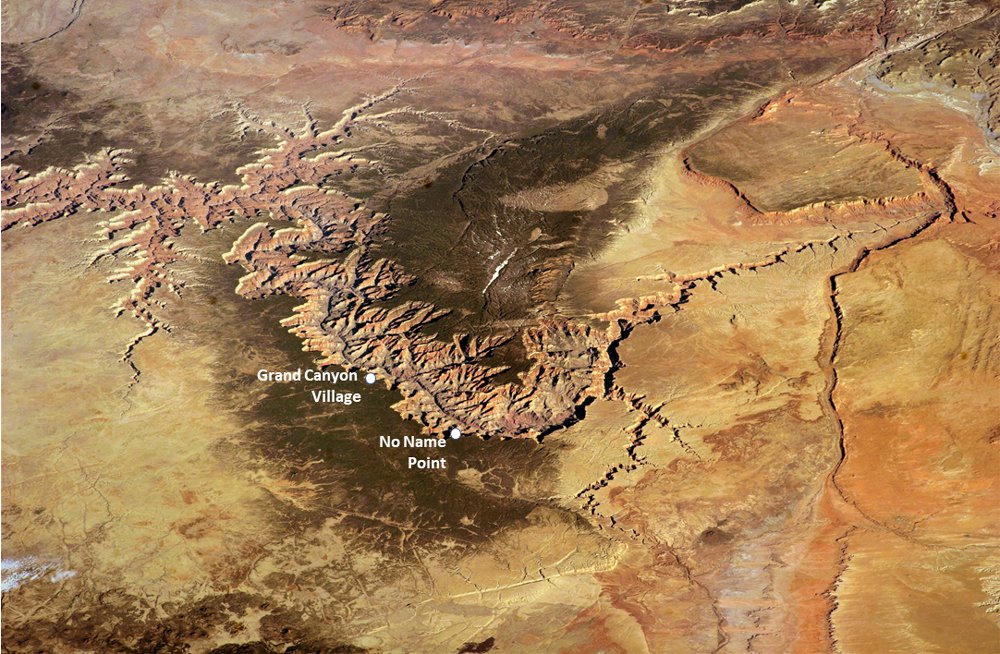

Fig. 1. Grand Canyon is positioned across the elevated Kaibab Upwarp in northern Arizona. No Name Point is ideally located at 7,100 ft elevation for discussion of erosion of Grand Canyon. Colorado River within the Canyon is at elevation of 2,545 ft. Oblique aerial view is toward the northwest along the axis of the East Kaibab Monocline. Upper Colorado River enters from upper right and flows into Grand Canyon at Kaibab Upwarp (higher elevation forested area in center) and exits photo on the upper left. No Name Point is 13 mi east of Grand Canyon Village. Width of this view is 100 mi. International Space Station photo ISS039-E-5258 acquired on March 25, 2014.

The morning of Sunday, April 10, 1988 began like most early spring days at the iconic landscape in extreme eastern Grand Canyon National Park. The location is at the Canyon’s rim in a place so obscure that National Park rangers refer to it simply as “No Name Point.” Although one never finds No Name Point located on maps, it does have a guard rail at the Grand Canyon rim. As the sun rose that morning and its rays grazed the extreme southeastern rim, the colors of the eastern Canyon wall began to gleam. The browns and grays of early morning soon became reddish, yellowish, and greenish hues as cliffs above the Colorado River reflected the increasing intensity of the sun. The normal chatter of ravens and squirrels began among the pine and juniper forest at the Canyon rim, but this Sunday morning was going to be something new and unusual. No Name Point was going to inspire a memorable discussion on the erosion of Grand Canyon (fig. 1).

Church on the Canyon’s Rim?

Fig. 2. People begin assembling at the lecture location called No Name Point on the rim of Grand Canyon. Here the third bus has just arrived. People interested in Grand Canyon erosion are getting seated. About 140 attended that lecture on Sunday morning April 10, 1988. Photo by John D. Morris.

Just after 9 a.m. on Sunday, April 10, 1988, a few cars appeared at the obscure gravel and pavement turnout adjacent to the Canyon rim. People stepped out of cars and began walking by trail northward through the forest to a railing at the Canyon rim. No Name Point began to bustle with activity. Then, a most unusual event occurred. Two large buses and more cars dispatched passengers as a hundred people assembled at the rail fence. Then, a third bus arrived! It may have been the largest assembly of Christians yet on the Canyon’s rim (fig. 2). People standing there began to marvel at the spectacle visible from that Canyon rim overlook at elevation of 7,100 ft. As the crowd squeezed together behind the railing at the Canyon rim, some sat on folding chairs, but most sat on the flat limestone surface. Then, Tom Manning, the event host, with a loud voice announced the remote assembly was to open in a prayer of thanksgiving. Almost spontaneously after the prayer, the crowd erupted in song with the words, “When through the woods and forest glades I wander . . . When I look down from lofty mountain grandeur . . . ” These words are the second verse from the well-known Christian hymn titled “How Great Thou Art.” It was apparent to all that this Sunday morning at No Name Point was to be a worship and teaching event at the rim of Grand Canyon! The park ranger couldn’t remember any assembly like that at No Name Point.1

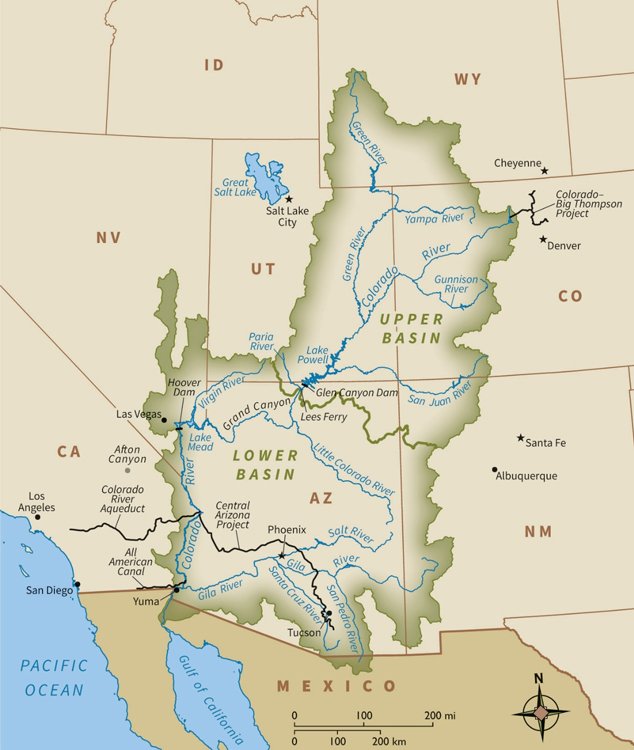

Fig. 3. Colorado River drainage basin extends into parts of seven states and Mexico. The drainage basin is divided into “lower basin” and “upper basin,” with the boundary being drawn by the Bureau of Reclamation at Lees Ferry on the river northeast of Grand Canyon. Blue lines show major rivers, and black lines depict canals and pipes which the Bureau of Reclamation uses to transport water for nearby urban areas. Copyright International Mapping Associates, used by permission.

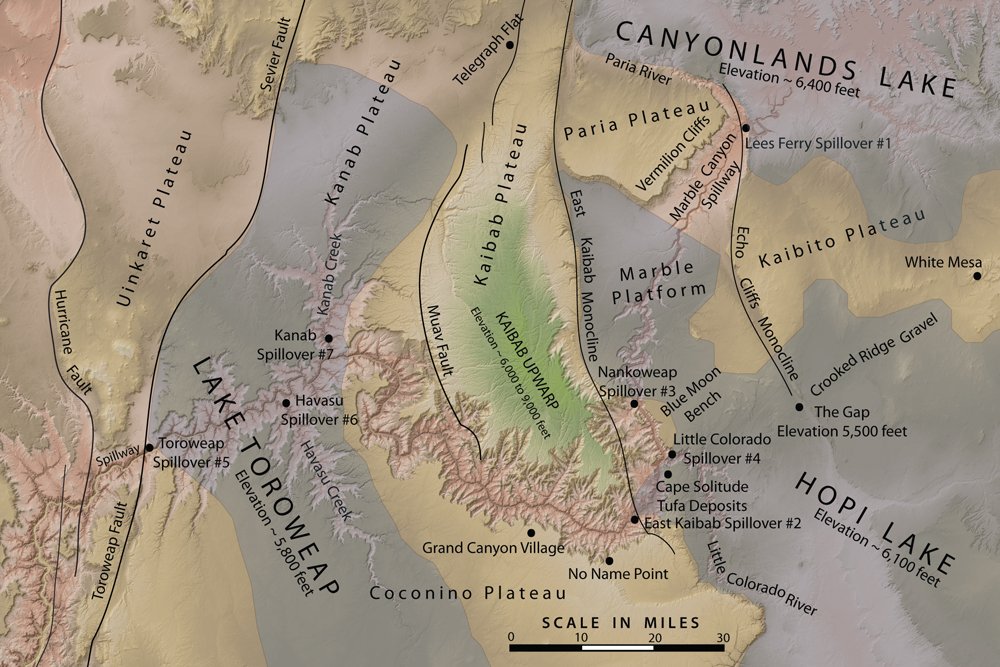

After some formalities at the Canyon rim, a Scripture from the Book of Job was read (“He cuts out rivers amongst the rocks . . .”) and a geologist, Dr. Steve Austin stood up and delivered a morning “message” titled “Erosion of Grand Canyon.” That teaching about Canyon erosion was unusual because it deviated from the expected explanation that the Park rangers give that the Colorado River eroded Grand Canyon very slowly over tens of millions of years. Instead, Dr. Austin reported evidence that Grand Canyon was eroded in just a few weeks just thousands of years ago by catastrophic drainage of lakes. The regional drainage of the entire Colorado River is conveniently divided into upper and lower basins (fig. 3). Austin explained that a computer plot of elevation data shows that an enormous lake or series of lakes bigger than one of the Great Lakes could be contained within the present topographic region extending from the lower to the upper Colorado River basins. The series of lakes could form east and north of Grand Canyon if the eastern Grand Canyon was plugged by an enormous dam. The location of ancient lakes affected the entire Colorado River drainage basin (fig. 4). Austin pointed to lime sediment layers east of Grand Canyon visible at distance from No Name Point as evidence that at least one ancient lake once sat above 6,000 ft elevation over Cape Solitude east of Grand Canyon (fig. 4). That lake was named Hopi Lake. Then, he described the topographic similarity of Grand Canyon to the spillway of a breached landscape at Mount St. Helens that was eroded in a single day on March 19, 1982.

Fig. 4. Eastern Grand Canyon location map shows the places and features used in discussions of the breached dam (spillover) hypothesis for erosion of Grand Canyon. Map includes Austin’s and Holroyd’s proposed locations of three ancient lakes and their seven spillover points. Shaded relief base map is from US Geological Survey 10m DEM processed using ESRI software.

That teaching about rapid erosion from spillover was well received by the crowd and a lively discussion about canyon erosion followed as the people dispersed that Sunday morning over 30 years ago. That teaching event on the rim of eastern Grand Canyon in April 1988 was an early statement of what has been called the breached dam hypothesis for the erosion of Grand Canyon.2

Are Spilling Lakes All It Takes?

How geologists started thinking about erosion of Grand Canyon is also an interesting story worth remembering. John Newberry in April 1858 was the first geologist to explore, interpret and report upon erosion in Grand Canyon (Newberry 1861; Newberry 1862).3 He recognized that strata were continuous through basins and arches, but strata continuity was broken by water erosion. But, what style of water erosion? Newberry wrote: “Doubtless in earlier times it [Colorado River] filled these basins to the brim. . . . its accumulated waters, pouring over the lowest points in the barriers which opposed their progress towards the sea, have cut them down from summit to base, forming that remarkable series of the deep and narrow canyons through which its turbid waters now flow. . . .” (Newberry, 1861, 19, 20). Newberry observed lake clay deposits (now called Bidahochi Formation) along the Little Colorado River, and he proposed lake overflow of the topographic surface of Arizona was the cause of Grand Canyon’s unique style of erosion. Notice that Newberry’s explanation was that the geologic structure (strata of uplifted plateaus, faults and folds) formed before the Colorado River eroded the surface. The river was the latest addition to the landscape, therefore, a “young river.” It was an extraordinary achievement. The first geologist ever to explore Grand Canyon, John Newberry, recognized in 1858 that it was carved by drainage spillover of what has later been called ancient “Hopi Lake.”

Observations in 1869 and 1871 on two river expeditions encouraged John Wesley Powell to think differently. Powell believed the Colorado River was older than those geologic uplifts and topographic barriers (Powell 1875). The issue was not what he could see, but what he could imagine. He supposed those uplifts were raised across the ancestral river’s path; therefore, he imagined the “old river” was antecedent to the geologic structure. Two other geologists Charles Walcott (Walcott 1890) and William Morris Davis (Davis 1901) added to Powell by suggesting that the “old river” exhumed older strata that once overlay the rim of Grand Canyon. They suggested the “old river” was superimposed as it was let down through strata and structure that have been removed, thus, explaining why there is a lack of evidence for the hypothesis! Again, prominent in geologists’ minds was what was not seen, and their presuppositional agenda as they interpret the river.

Seventy years after Newberry’s spillover explanation, geologists in the early 1930s were carefully studying the lower Colorado River corridor for a site to build Hoover Dam and Lake Mead. One of these was Eliot Blackwelder, chairman of the Geology Department at Stanford University (Blackwelder 1934). Another was Chester Longwell, professor of geology at Yale University (Longwell 1928). Both Blackwelder and Longwell were proficient at distinguishing river gravels and river sand from lake-deposited clay and limestone. Focus of study was the area directly west of Grand Canyon, the region around today’s Lake Mead (fig. 3). That is the area described by Newberry. Blackwelder and Longwell identified Pleistocene river sediment sitting directly on top of thick Pliocene green clay, limestone and gypsum salts (what was called Bouse Formation). Blackwelder recognized a straightforward explanation, and he knew that Newberry had already understood the issue 70 years earlier.4 Like Newberry, Blackwelder suggested the Southwest was once a series of closed drainage basins with big lakes.5 He imagined, “a chain of lakes strung upon a river” (Blackwelder 1934, 562). He supposed highlands with basins between that filled forming lakes that eventually overtopped barriers spilling as rivers and eroding bedrock canyons into the adjacent basins. He visualized a “young river” where a lake overflowed Kaibab Upwarp.

One of Blackwelder’s perceptive insights was that a spillover explanation ought to apply to landscapes outside the Colorado River drainage. Elmer Ellsworth, Blackwelder’s graduate student, described the noteworthy example in 1932 at Afton Canyon on the Mojave River in Southern California. Like Grand Canyon, Afton Canyon was understood to have been eroded across a mountain by catastrophic drainage of a big lake (Blackwelder and Ellsworth 1936). By 1936 the mudstone and sandstone strata of the Bidahochi Formation were formally recognized by geologist Howel Williams to be a deposit from an ancient lake in eastern Arizona. Williams (1936) proposed ancient “Hopi Lake” (aka “Lake Bidahochi”), a 12,000-square-mile-area lake that occupied the basin on the east side of the Kaibab and Coconino plateaus at elevation above 6,000 ft. Scientists at that time began to use the technical term “transverse drainage” to describe rivers with canyons that cut across mountains. Things looked promising for the spillover explanation of Grand Canyon.

However, the second half of the twentieth century was the time that geologists embraced uniformitarian doctrine to such an extent that theories of landscape evolution were championed. That thinking expressed itself in the former century’s “old river” Grand Canyon erosion narrative that still pervades our culture. According to the narrative, rivers evolve landscapes through tens of millions of years of erosion from lowlands to highlands. That process is called “headward erosion,” or, more correctly “drainage-head erosion” (Hilgendorf et al. 2020). Canyons are part of landscapes that evolve slowly from the bottom up (“headward”). The process of “stream capture” is supposed to involve a precocious gully that eroded headward from the west to the east across Kaibab Upwarp diverting the upper drainage basin toward the Pacific Ocean. Those earliest explanations of Newberry, Blackwelder, and Williams understood erosion to occur over high-country barriers, then extending into lowlands. Spillover was erosion from the top down, backwards from the uniformitarian doctrine. As the last half of the twentieth century unfolded, spillover was lost from memory. According to Dr. Norman Meek the twentieth century was the time when “ponding and overflow became the forgotten transverse drainage hypothesis” (Meek 2002).

Fifty years ago, three creationists explored Grand Canyon erosion ideas, affirming what had become a long-established creationist consensus.6 Dr. Clifford Burdick, geologist from Tucson, supposed late Flood uplift and ponding of water behind the Kaibab Upwarp with the unnamed lake on the east side breaching in the post-Flood period to erode the Canyon.7 Dr. Henry M. Morris, Jr., who affirmed Byron Nelson’s (1931) timing of post-Flood erosion, spoke favorably of Burdick’s detailed explanation of rapid post-Flood drainage of a big lake (Whitcomb and Morris 1961).8 Dr. Bernard Northrup, seminary professor in Old Testament from San Francisco, favored post-Flood elevation of the Kaibab Upwarp, followed by basin filling forming enormous “Lake Kaiparowitz” that was quickly breached forming Ice Age meltwater floods.9 Dr. Austin recalls, “In 1968 I spoke privately about Grand Canyon with Henry Morris when he was speaking at University of Washington in Seattle. Also, in 1968, Ed Nafziger, a Seattle science teacher and veteran Grand Canyon hiker, introduced me to Cliff Burdick and Bernie Northrup. Burdick, Northrup and I did field work together in summer of 1968. These men not only transferred to me a passion for exploring Grand Canyon, but an understanding of spillover as a powerful erosive agent that could carve solid rock layers in the years after Noah’s Flood.” I am humbled to recall these discussions about Grand Canyon erosion. I reflect on the possibility that, at that time, we may have been the only people on planet earth that were talking about spillover.”

A Memorable Lunch Discussion

Eighteen years after Austin’s field work with Burdick and Northrup, three scientists remembered those erosion ideas. It was a lunch meeting in the cafeteria at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh in August 1986. The three scientists were Dr. Steve Austin, professor of geology at Institute for Creation Research Graduate School, Mr. David McQueen, also professor of geology at Institute for Creation Research, and Dr. Edmond Holroyd, physicist with the US Bureau of Reclamation in Denver. The Pittsburgh lunch discussion in 1986 among the three scientists concerned the erosion of the Colorado Plateau including Grand Canyon. Figs. 3 and 4 are maps showing the locations and features that were points for discussion.

McQueen recalls that Pittsburgh meeting, “Dr. Austin talked about his observations that the silt deposits near Hopi Buttes, Arizona indicate that a very large and high elevation ancient lake existed behind the Kaibab Upwarp in northeastern Arizona that others had called Hopi Lake. He suggested also that sediment deposits on the extreme eastern rim of Grand Canyon could be evidence of that big lake extending westward from New Mexico through Hopi Buttes a distance of 200 miles to the Kaibab Upwarp.” At that meeting in Pittsburgh, Austin described a “campfire discussion” on closed-basin spillover in April 1985 with geology graduate students while camped at Horseshoe Mesa in eastern Grand Canyon. Two of those geology graduate students wrote term papers on Grand Canyon erosion. John Whitmore’s term paper affirmed evidence for Hopi Lake and the proposition that the lake spilled over the Kaibab Upwarp (Whitmore 1985). Austin had just given a paper at the Pittsburgh meeting on the similarities between Grand Canyon and the newest landscape at Mount St. Helens that was breached by an overtopping mudflow on March 19, 1982 (Austin 1986). At that same Pittsburgh lunch discussion in August 1986, Holroyd explained how, from his Colorado home in Montrose, he frequently conducted field study of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River. That canyon, he noted, is very similar to Grand Canyon. Holroyd also related that through his government-office computer he had access to a US government digital elevation model (DEM) and that he could plot the lake shoreline that could be contained by the present topography if Grand Canyon was blocked by a gigantic dam. McQueen recalls, “Dr. Holroyd was most interested in how the series of lakes drained, and how drainage could shape landforms upstream of Grand Canyon, especially cliffs on the Colorado Plateau that seemed to lack significant sandstone blocks on the margin with the valley.” Together, these three scientists (Austin, McQueen, and Holroyd) agreed to study these landforms of the Southwest more carefully.

Mapping a “Big Series of Lakes” on the Colorado Plateau

Late in 1986 Ed Holroyd conducted a survey of the digital elevation model (DEM) data available through the Bureau of Reclamation. These elevation data were originally derived from 1 × 2° topographic maps at scale one-inch equals six miles (scale 1:250,000) and typically 200 ft contour interval. The horizontal geographic resolution (30 arc seconds) was adequate for the regional analysis that was to be performed, but the elevation resolution (± 200 ft from contour maps) was of marginal acceptance for the tasks the computer was being asked to perform. Compare that original data set available to Ed in 1986 to modern data sets. Today’s state-of-the-art elevation databases (modern DEM’s) typically contain laser-aircraft measurements (called LiDAR) of the earth’s solid surface elevation, even through dense forest cover, to horizontal and vertical accuracy of plus-or-minus 1 m (3 ft).

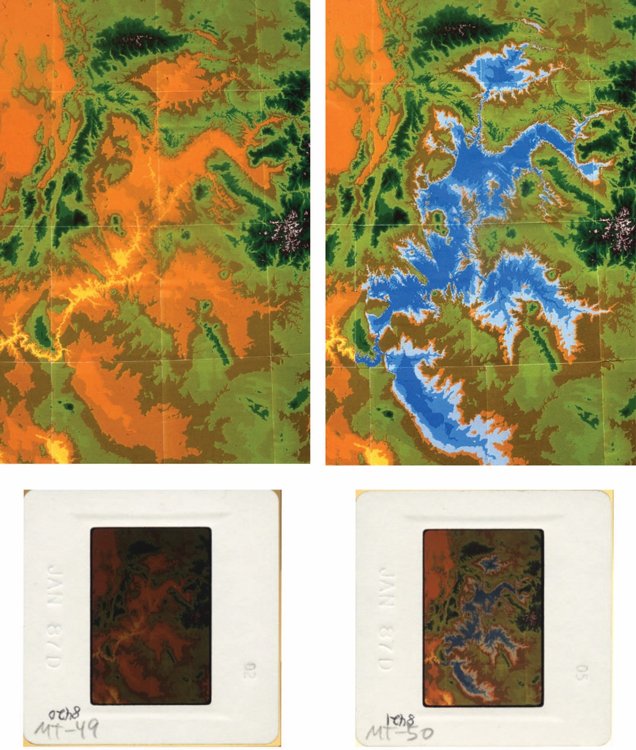

Fig. 5. Edmond Holroyd’s copy slides of the two original paper elevation maps of the Colorado River drainage basin. Left shows the computer-generated image “without lakes,” and right shows the image “with lakes.” Below both digital images are the scanner copy of the cardboard Kodak mounts with enclosed processed Ektachrome film.

In 1986 Ed Holroyd understood the Bureau of Reclamation elevation data to be satisfactory for the regional analysis he intended to perform. Next, he used a scientific programming language called FORTRAN to plot elevations as colors on a geographic grid.10 He produced two plots, one a regional elevation chart “without lakes” (fig. 5, left), and the other a regional elevation chart “with lakes” (fig. 5, right). The “with lakes” version has a “nominated surface elevation” of 1,700 m inserted into the computer code with lake depths shown in shades of blue. Holroyd could have inserted “nominated surface elevation” of 1,800 m, but the lake would spill out of its basin. He could have chosen 1,600 m, but the lake would only partly fill the basin. Holroyd was also acutely aware of the ± 200 ft topographic error in the data sets.

How fig. 5 was produced is an extraordinary achievement considering the computer technology available in 1986. Paper output from a color printer was limited to geographic extents of 2 × 2 degrees of latitude/longitude because of the original data sets. So, the 2 × 2 color prints were “tiles” used to assemble a regional mosaic. As one might expect using 1986 technology, “tiles” were pages from the color printer that were cut by hand and taped together into a regional mosaic. Holroyd says, “In 1986 this tile assembly process might be styled as an innovative solution. Today, as we recall it, we laugh and dismiss it as archaic.”

So, with limited technology, Holroyd constructed two charts. The two color-paper, hand-taped mosaics were formed, one chart “without lakes” and one “with lakes.” Original Ektachrome 35 mm slide-film photographs of each mosaic (fig. 5, bottom) each display Kodak’s date stamp “JAN87D” embossed into the paper frame. The slide photographs also bear pencil notations “MT-49 and “MT-50,” the slide sequence numbers for Holroyd’s “Missing Talus” oral presentation at the 1990 International Conference on Creationism (Holroyd 1990b). These two Ektachrome slides (fig. 5, bottom) are the January 1987 originals from which are made the transformations by today’s digital-scanning technology (fig. 5, top). Notice that traces are visible of the 2 × 2 degree tile grid from which they were prepared.

Office Politics

How did Holroyd interface with the Bureau of Reclamation office about his work associated with the DEM? Holroyd says: “In early 1987 I asked a supervisor about the possibility of eventually publishing an article presenting the ancient lakes of the Colorado Plateau as glacial, like Ice Age Lake Bonneville in Utah. I showed the supervisor the color 8 × 10 in prints of the big series of lakes. He responded by strongly threatening with the loss of my job because of unauthorized use of government computer and property. However, it was an extension of my regular DEM work and amounted to only a few extra lines of FORTRAN coding. In fear, I burned the original paper mosaics and the color prints. I only retained the original 35 mm Ektachrome slides. These I eventually used in my two oral presentations at the International Conference on Creationism in 1990. With regard to the DEM work, I had to go into hiding, and I needed to keep quiet about what I had found. I felt like I was carrying the Precious Child in flight to Egypt to avoid murderous King Herod! Yet, to have my findings distributed, I authorized Steve to make use of my lakes outline without mentioning my name as the source.” Austin says, “Both Dave and I recognized the serious problem that Ed was enduring. We honored him by avoiding his name in any description of the DEM work. A coping strategy I had learned, when one encounters a difficult problem, is to tell oneself that the problem could be worse. One day in early 1987, as Dave and I joked, we recalled Ed’s problem. One of us imagined what could happen if Sierra Club got wind of what Ed was doing. We jested about a newspaper headline: Bureau of Reclamation Scientist Designs 3,000-Foot-High Dam for New Lake in Grand Canyon.” Yes, that would be a much bigger problem!

In his note in the June 1987 issue of Creation Research Society Quarterly, Holroyd wrote, “One could also imagine a series of lakes if the Colorado River was plugged by high ground between the Kaibab and Coconino Plateaus at about the Grand Canyon Visitor Center. A lake surface at about the 1,700 m (5,600 ft) level could be supported by the present regional topography without the water spilling out over another divide to the north. The resulting series of lakes along the Colorado, Little Colorado, Green, and San Juan Rivers would resemble several of the Great Lakes in size. (Some believe that the sudden release of such a great quantity of water through a fault-generated crack between the north and south rims of the Grand Canyon near the Visitor Center is responsible for the bulk of the carving of the Grand Canyon.)” (Holroyd 1987). Notice that in this June 1987 publication Holroyd was speaking with round numbers and trying to encourage other workers to investigate lakes of the Colorado River drainage basin. Holroyd said nothing about having already plotted the lakes on his computer.

How Does One Describe Lake Elevation?

The U.S. government DEM (digital elevation model) used by Holroyd in 1986 has elevations in meters derived from topographic maps with typically 200 ft contour interval at 1:250,000 scale (1 in equals about 6 mi). The analysis of Holroyd with “nominated surface elevation” of the lake shore plotted at elevation 1,700 m (5,577 ft). But how much higher could the lake fill before overtopping the modern terrain? That question was directing Ed, Steve, and Dave to imagine the lake’s elevation relative to another hypothetical level called a “pour point.” The DEM, because of the ± 200 ft errors, could not supply the terrain pour point answer. We needed much better data than the 1986 DEM. Analysis of the detailed 1:24,000 scale topographic maps of Telegraph Flat area east of Kanab, Utah showed that the water could rise today to about 5,616 ft (about 1,712 m) before it would spill to the southwest through the modern drainage gap in Moenkopi Formation mudstone that is 20 mi east of Kanab, Utah (location in fig. 4).11 The elevation of the Telegraph Flat pour point is not known exactly. Recent ASTER satellite elevation data indicate the 1:24,000 scale USGS contour map is poorly drawn near the potential “pour point” and contains error of 10 ft or more. The recent ASTER data indicate the pour point is actually closer to 5,626 ft.

Another, very intuitive way to refer to the lake’s elevation would be simply by the height of the feasible dam consistent with the overall modern topography. The height of the feasible dam should be just above the terrain pour point. Teachers know that talking about terrain this way connects with students.

So, there are three ways to express the lake’s elevation: (1) nominated elevation, (2) pour point elevation, and (3) height of the feasible dam. Austin, Holroyd, and McQueen believe the best way to communicate this elevation is by speaking about the height of the dam. That elevation should be expressed as a round number. Therefore, the elevation of the dam should be rounded to the next 100 ft above 5,616 ft (the underestimate of the pour point elevation). The question can be stated, “What is the elevation rounded to the nearest 100 ft of the dam that could contain the maximum amount of water above present Grand Canyon?” Austin and Holroyd calculated the answer to that question in March 1987 in order to write the caption to a bulletin-board map. The answer is 5,700 ft (the rounded elevation of the dam that would form the largest hypothetical lake). Notice, there is only one right answer to the question as it was stated. That one correct answer is 5,700 ft. Rounding upward is good engineering practice because the crest of the dam needs to be higher than the lake it is designed to contain. Also, rounding upward was beneficial for office politics reasons because it further distanced the map from Holroyd’s metric computer plot.

The Bulletin-Board Map

Ed Holroyd recalls how the map was transferred: “I sent a non-colored version of the extents of the lakes to Steve Austin in San Diego in January 1987. Back then we did not have screen-sharing or screen-printing technology, so it was impossible to share directly my computer screen in Colorado with scientists in San Diego. So, I did it the old-fashioned way by exchanging photography through the US Postal Service.”

Fig. 6. The bulletin-board map that was posted in 1987 for graduate students and faculty. The caption attached to that map read, “A computer was asked to draw the shoreline of the lake which would form behind the Kaibab Upwarp if the Grand Canyon were blocked at the 5,700-foot elevation.” The data was rendered on Ed Holroyd’s computer (fig. 5, right) and the map was drafted by Steve Austin from the Ektachrome transparency (fig. 5, lower right). The map with caption was first published in March 1989 by Austin, and two different renderings were published by Holroyd in 1990 and 1994.

Austin was interested in Holroyd’s progress in terrain analysis. Austin remembers, “After Holroyd had completed the DEM analysis, he loaned me a black-and-white photographic print of the series of hypothetical lakes on the Colorado Plateau. The print was about 8 in wide with washed out details from Ed’s much larger, color rendition. In January 1987 I traced the print photo onto clear acetate and added several familiar geographic features and the state boundaries. I had trouble tracing through washed out detail. Over the tracing I wrote ‘Lake Kaibab’ intending it to depict a series of lakes east and north of the Kaibab Plateau. I promptly returned the print photo to Holroyd by the Postal Service requesting the higher resolution color version. I retained the acetate tracing of Holroyd’s print photo in my archive.” Holroyd provided the 35 mm color film through the Postal Service in February 1987.12 In March 1987, Austin more accurately replotted the shoreline film onto the distribution of familiar topographic features producing for the first time, on a sheet of paper in prepublication form,13 a user-friendly and thought-provoking lake map (fig. 6). Of course, such a sketch map requires a caption with words describing what the map is attempting to depict. Both Austin and Holroyd composed the caption during a phone conversation in March 1987. Dr. Holroyd remembers he and Austin agreed that the map’s caption would read, “A computer was asked to draw the shoreline of the lake which would form behind the Kaibab Upwarp if the Grand Canyon were blocked at the 5,700 ft elevation.”14 Together in early 1987, Holroyd and Austin composed those words including the elevation 5,700 ft.

Because of his association with the government database, and because of the office problem with the boss at Bureau of Reclamation in Denver, Holroyd asked that the map (fig. 6) not be published immediately. However, he agreed that Austin and McQueen could talk about the work generally (without mentioning Holroyd as the data source) and post Austin’s sketch map with caption in a non-public venue. Early in 1987 the map with caption was posted on the bulletin board of the Institute for Creation Research Graduate School, in Santee, California.15 Dave McQueen recalls, “I’ve never seen a bulletin board that compares. It was not attached to the wall but was freestanding in the front of the Geology classroom. As you walked up to it, you recognized it to be a hinged, flip display with several 30 × 40 in boards forming a ‘book’ of geologic maps. The huge vertical format caught everyone’s attention. It was the 1987 analog of today’s social media; whatever was posted became a topic of conversation. On page 3 of the book of maps was the computer-fit series of lakes on the Colorado Plateau.” That bulletin-board posting focused attention on the question, “How were the ancient lakes configured?” The bulletin-board map suggested the series of lakes could extend into four states (Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado) being as big or bigger than Lake Superior!

In June of 1987 Holroyd published his short note on “Missing Talus” to stimulate new research (Holroyd 1987, 15, 16). Gravity causes accumulation of boulders at the bases of slopes below cliffs that form steeply inclined rock piles called talus. If slopes backwear slowly during millions of years, the base of associated slopes should have substantial talus. Holroyd says: “I pointed to shale slopes with sandstone capping strata at Mesa Verde, Grand Junction, Book Cliffs and Monument Valley. Sandstone blocks should litter the shale valley floors. Where did those blocks go? One possibility is that a lake shore was up against the slope with wave action abrading the boulders. Another possibility is that catastrophic drainage of lakes could have swept sandstone blocks from those valleys. In my 1987 paper I stated in words that one could imagine “a big series of lakes” on the Colorado Plateau. What I didn’t say was that I had already plotted the possible lake shoreline on my computer! By publishing this mid-1987 note in Creation Research Society Quarterly, I notified the creation community of what I discovered in late 1986 by this Colorado Plateau terrain analysis. Thereafter, anyone could reproduce the lake simulations.”

Early in 1988, Ed Holroyd was transferred to a different working group within Bureau of Reclamation. Specified in Ed’s new job description was doing remote sensing and mapping research. Also, in early 1988, Ed transferred the DEM computer code to his home computer taking the work away from government computers. Talk about the “big series of lakes” and “blocked at the 5,700 ft elevation” changed in the spring of 1988. Holroyd had made his home-office computer render DEM and satellite imaging software, now making new home-office plots clearly in the public domain. So, Austin requested to publish the “blocked at 5,700 ft elevation” map (letter to Holroyd, January 23, 1989) and Holroyd (letter to Austin, February 2, 1989) gave permission. Finally, after being posted on the bulletin board for two years, the “blocked at 5,700 ft elevation” map was distributed by publication in March 1989.

Tectonic Tilting of Kaibab Upwarp

Also, in the summer of 1987, graduate school classes continued in San Diego with faculty and students expressing their opinions on the bulletin board map. Austin suggested that the actual ancient configuration of post-Flood lakes was somewhat different than suggested by the map. According to Austin, important topographic change occurred by tectonics and isostacy after drainage of the lakes. Understanding the tectonic change since the lakes existed, allows us to visualize more accurately the original lake basins and their bedrock dams.

As one stands on the South Rim at Grand Canyon Village and looks north and northwest, the strata of the Kaibab and Kanab plateaus on the far side of the Colorado River appear to be perfectly flat and level with the horizon. That is the iconic image that we all have of Grand Canyon. However, that impression of strata flatness is an illusion created by our viewing angle. If one pays attention to the Kaibab Formation at the Canyon rim and follows it northward through the Kanab and Kaibab plateaus, that formation decreases over a thousand feet of elevation before reaching the Utah border! Therefore, the Kaibab Formation is really inclined, dipping northward at over 50 ft per mile (over 10 m per km) through a distance of 40 mi. All of the plateaus in Arizona north of the Colorado River have substantial northward inclination (up on the south sides, down on the north sides). Austin considers Kaibab Upwarp and most of the monocline structure of Kaibab Plateau formed before Canyon erosion. That early formed structure confined Hopi Lake topographically. However, Austin suggested that a major part of the tilting of the Kaibab Plateau occurred after spillover erosion of Grand Canyon. Therefore, Austin suggested that more than 1,000 ft of present elevation needs to be removed from the south end of Kaibab Plateau to approximate the configuration of the East Kaibab Spillover when the structure was breached. Also, Austin proposed that more than 1,000 ft of elevation needs to be added to the north end of Kaibab Plateau near Telegraph Flat at the time of spillover. As early as 1987 Austin postulated rotational plateau tilting (up on the south, down on the north) was likely associated with the oblique strike-slip shear that continued after monocline flexure. That was Austin’s “tectonic tilting hypothesis” for Kaibab Upwarp formulated in late 1987. Geologists, lately, are still discussing the tectonic process, especially the “Pliocene and Pleistocene uplift” of the southern margin of the Colorado Plateau.

In addition to tectonic uplift of the south end of the Kaibab Plateau, one needs to imagine likely hundreds of feet of isostatic uplift because of the removed weight of sediment within the eroded canyon and plateau. Isostatic uplift also likely occurred by the removal of the weight of upstream lakes. Austin comments: “A noteworthy cluster of recent earthquakes occurs under the Kaibab Upwarp. Continued faulting appears to have uplifted the southern Kaibab Plateau many hundreds of feet after the Kaibab dam was breached. Some elegant structural geologic models have been developed to explain the recent northward tilting of the Kaibab Plateau that allows us to visualize the original configuration of the Kaibab dam.”

There’s Power in the Flood!

Among the participants in the April 10, 1988 rim lecture at Grand Canyon was Paul MacKinney. Paul was a concrete engineer from Illinois with a special interest in Grand Canyon erosion. As early as 1985 Paul was calling attention to spillway erosion, especially the process of cavitation, whereby fluid vacuum bubbles form in high-velocity floods. Paul pointed out how shallow, high-velocity flow creates very low-pressure fluid around channel obstructions, creating vapor bubbles within the fluid. Those bubbles are vitally important because they implode inflicting explosive forces on rock spillways. The process of cavitation can produce greatly accelerating bedrock erosion on a colossal scale. As a real-world example of cavitation erosion, Paul pointed out the catastrophic failure of the concrete-and-steel-reinforced left spillway tunnel at Glen Canyon Dam (location in fig. 3). In June 1983, during an emergency water release, discharge of 93,000 cubic feet per second was sustained through the left tunnel. During that emergency release, earthquakes were felt within the dam, and the “rooster tail sweep” exiting the tunnel turned distinctly red! After shut-down of the spillway tunnel, engineers found at an elbow within the tunnel a new 63,000-cubic-feet-volume hole penetrating concrete, steel and bedrock. Paul believed the enormous erosion in the left spillway tunnel could have happened because of cavitation within seconds.

Paul wanted to stimulate technical study of cavitation so he encouraged his creationist friends Cliff Paiva and Ed Holroyd. Cliff Paiva completed his master’s thesis on cavitation in 1988 (Pavia 1988). As a physicist with Bureau of Reclamation in Denver, Holroyd closely followed the government’s study of cavitation after the 1983 Glenn Canyon Dam cavitation event (Falvey 1990). Holroyd wrote computer programs to simulate cavitation erosion on scales never observed by humans (Holroyd 1990a). Just below No Name Point in Grand Canyon is Papago Creek. Holroyd wrote computer simulations of spillover erosion down Papago Creek through a channel 1,000 ft wide with initial flow speed of 10 m per second (Holroyd 1990b). Catastrophic bedrock erosion occurred in the simulation. After 1985, popular breached-dam lectures on Grand Canyon erosion often described how cavitation can erode spillways catastrophically. After one lecture on the Canyon Rim, an attendee was humming a familiar Christian hymn, then he sang the concluding words: “There’s Power, Power, wonder-working Power, in the overflowing flood of the dam!”

Holroyd’s Backyard

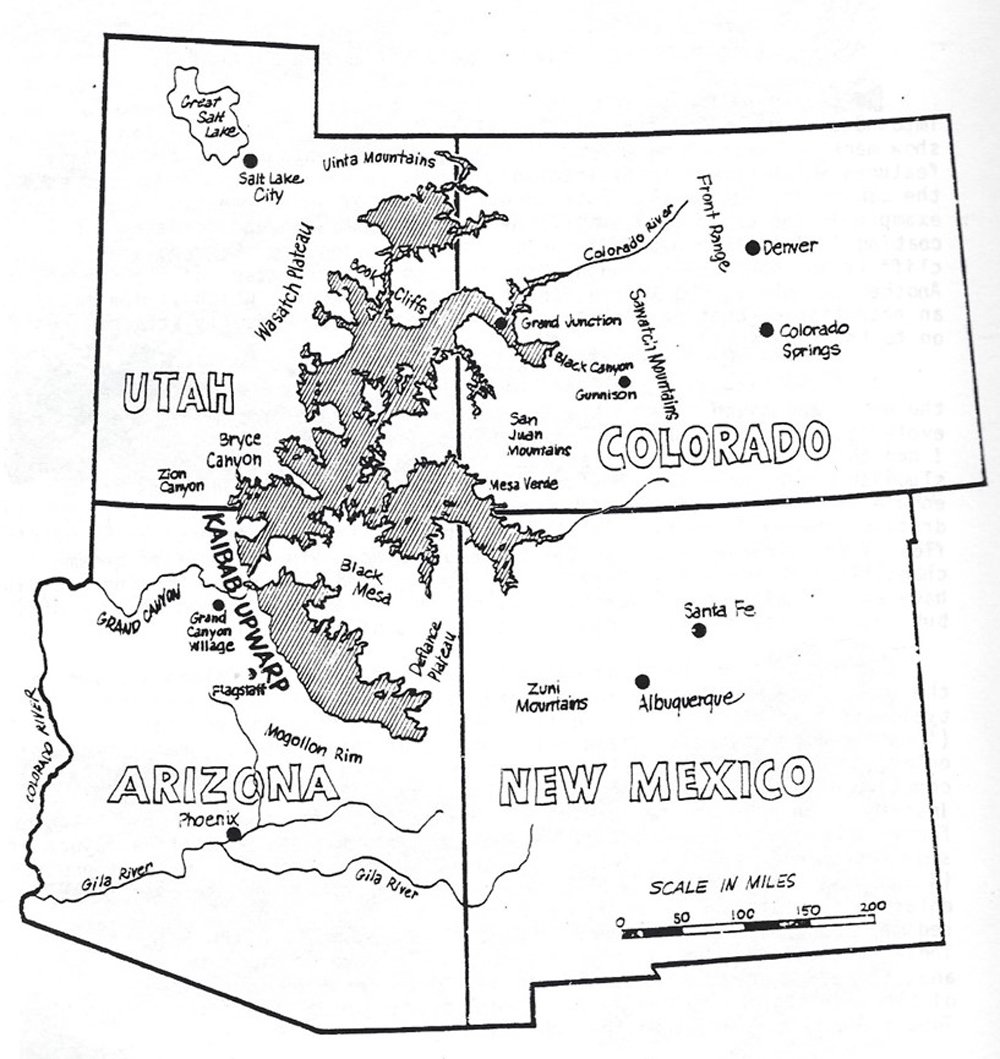

Fig. 7. The amazing course of the Gunnison River in southwestern Colorado. Foreground width is 18mi. View is here toward the southeast. Ed Holroyd noted that Black Canyon of the Gunnison (right-middle of this view) is positioned through elevated terrain that is aligned parallel to the axis of arched strata between two faults. Ed also noted a topographic low at “Cimarron Spillover” that appears to support his “crack-and-capture hypothesis.” Ed Holroyd’s home in Montrose, Colorado is just off the lower right corner of this view. (Landsat 8 photo acquired September 24, 2013.)

Dr. Ed Holroyd lived in Montrose, Colorado, from 1983 to 1988, adjacent to what is now the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park. That region, which displays the amazing course of the Gunnison River in southwestern Colorado, is displayed in fig. 7. The Gunnison River drainage begins in the topographic saddle in the upper right corner of fig. 7 between the West Elk Mountains (upper left of figure) and the San Juan Mountains (off the upper right corner of fig. 7). Then, between the Red Rocks and Cimarron faults, the Gunnison drainage turns abruptly northwestward (right side fig. 7) and enters the extraordinary gorge of Black Canyon. Then, after departing Black Canyon, the Gunnison drainage turns northward (foreground of fig. 7). Finally, the Gunnison River turns westward again, exiting in the front left corner of fig. 7. Holroyd says: “I sought to understand how Gunnison River was established across this fascinating landscape. I enrolled in the college course Geology of Southwestern Colorado offered by what was then Western State College, Gunnison. From that class and working with hand analyses of geological and topographic maps of the Black Canyon region, I sought to understand the geologic history of the canyon and its region. I read carefully the explanation published by USGS geologist Wallace R. Hansen (Hansen 1965). I even discussed the landscape with Wally Hansen in 1986. Both the college course and the USGS geologist promoted the headward erosion and antecedent “old river” hypothesis to explain how the Gunnison River eroded upstream along the same course from the ancestral Gunnison River. I recognized that explanation is the same as the classic twentieth century story for Grand Canyon!” So, fig. 7 shows the magnitude of this river course location problem.

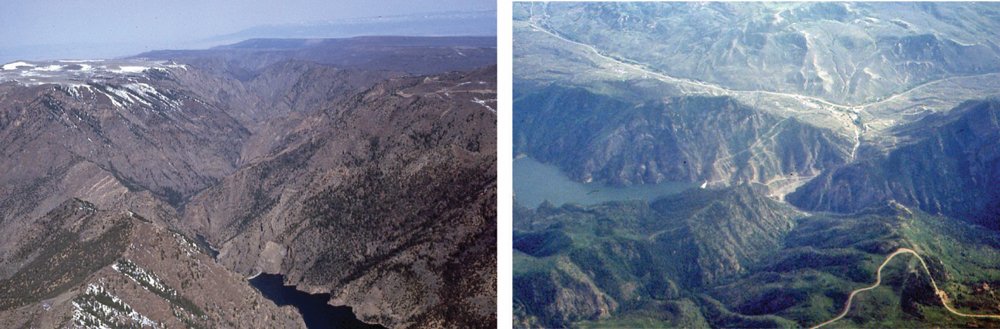

Fig. 8. Oblique aerial photos above “Cimarron Spillover” on the Gunnison River. Left image is looking northwest above the spillover where Gunnison River enters from the bottom right, turns abruptly to the northwest and enters upper Black Canyon. Right image is looking southwest above the village of Cimarron and the spillover where the Gunnison River should have continued westward into the soft shale in the lowland (upper right), but instead turns into upper Black Canyon (lower right). Ektachrome slide photos by Edmond Holroyd. Left image is from overflight on 29 March 1986, and right image is overflight on 23 June 1987.

One detail of the Gunnison landscape fascinated Holroyd. That is the turning point, where between the Red Rocks and Cimarron faults, the Gunnison River enters Black Canyon. There appears to be a low point in the terrain as shown in fig. 8. Holroyd comments on fig. 8: “I was impressed by oblique views in overflight. Gunnison River should have maintained its westerly course out of the high country into the incredibly soft Mancos Shale at the village of Cimarron. That should have occurred if the classic ancestral river story is correct. I noticed in overflight that the strata at the entry of Black Canyon form a broad arch structure with the river and canyon parallel at the top of the arch between the two faults. What I saw convinced me that overtopping occurred at what we can call Cimarron Spillover. These observations led me to propose cracks in the bedrock. An arch structure is where one would expect tensional cracks that open upward, and, because of overtopping, could direct erosion into high country.” That was the genesis of what Holroyd calls his “crack-and-capture hypothesis.”

Lees Ferry Spillover

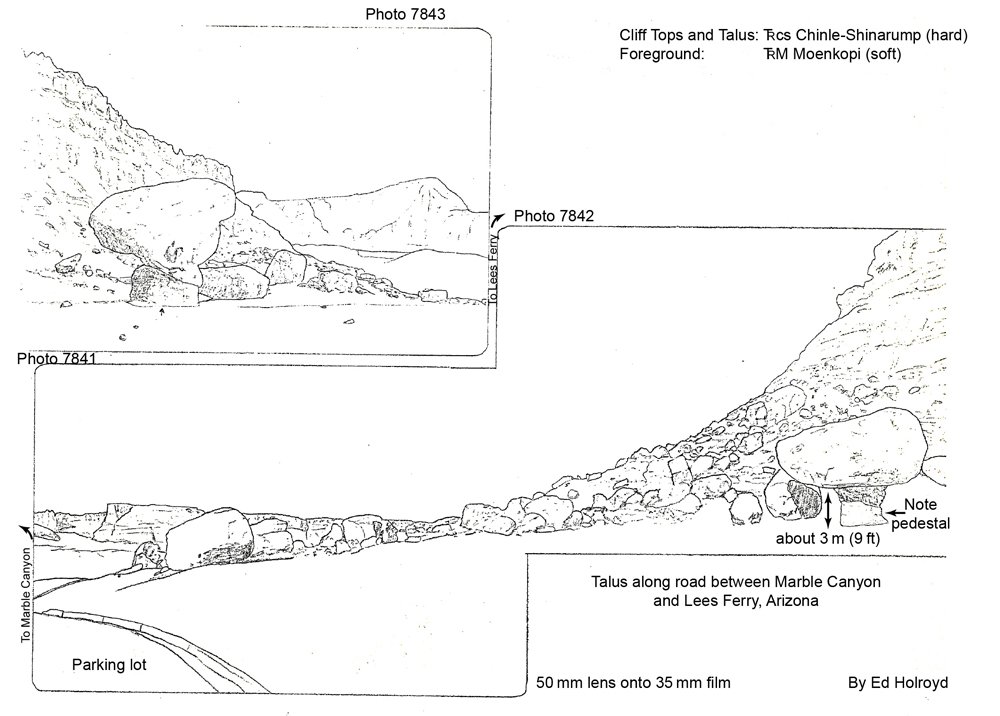

Fig. 9. Ed Holroyd sketched the talus slope at the base of the cliff at the pullover parking area between Marble Canyon and Lees Ferry. Hard and grey Shinarump talus boulders are a remarkably thin deposit lying on the soft and red Moenkopi Shale. Holroyd recognized in July 1987 that paucity of talus at Lees Ferry argues this cliff did not backwear through millions of years, but that the slope was recently swept by a catastrophic spillway flood. The two sketches were drawn from Ektachrome film by Holroyd in fall of 1987.

During July 1987, Holroyd drove from his home next to the Cimarron Spillover in southwestern Colorado to Marble Canyon, Arizona, just northeast of Grand Canyon. His paper “Missing Talus” had just been published and observations of Gunnison landscapes were on his mind. Holroyd was impressed with the central location of Lees Ferry between the upper and lower Colorado River basins (location in fig. 3). At Lees Ferry, Arizona in July 1987 he inspected Moenkopi Shale slopes below classic Shinarump Conglomerate cliffs. In fall 1987 Holroyd drew two sketches from slides of cliffs at Lees Ferry without significant talus (fig. 9). Here is how Ed explained that cliff in a phone conversation with Steve Austin: “The phone conversation was in December 1987. I explained to Steve my computer DEM plot of Prospect Lake that had formed within Grand Canyon by the lava dam at Vulcans Throne. Prospect Lake as I plotted it on present topography reached to Lees Ferry. My original thought before my July 1987 field trip was that the lake’s shoreline stood at the base of the cliff above Lees Ferry. Then, I saw the missing talus confirmation in July 1987 during my field work. Steve suggested on the phone a bigger lake upstream that spilled over and swept talus away. So, I was ready to describe the spillover point at Lees Ferry in a research proposal that I wrote in January 1988.”

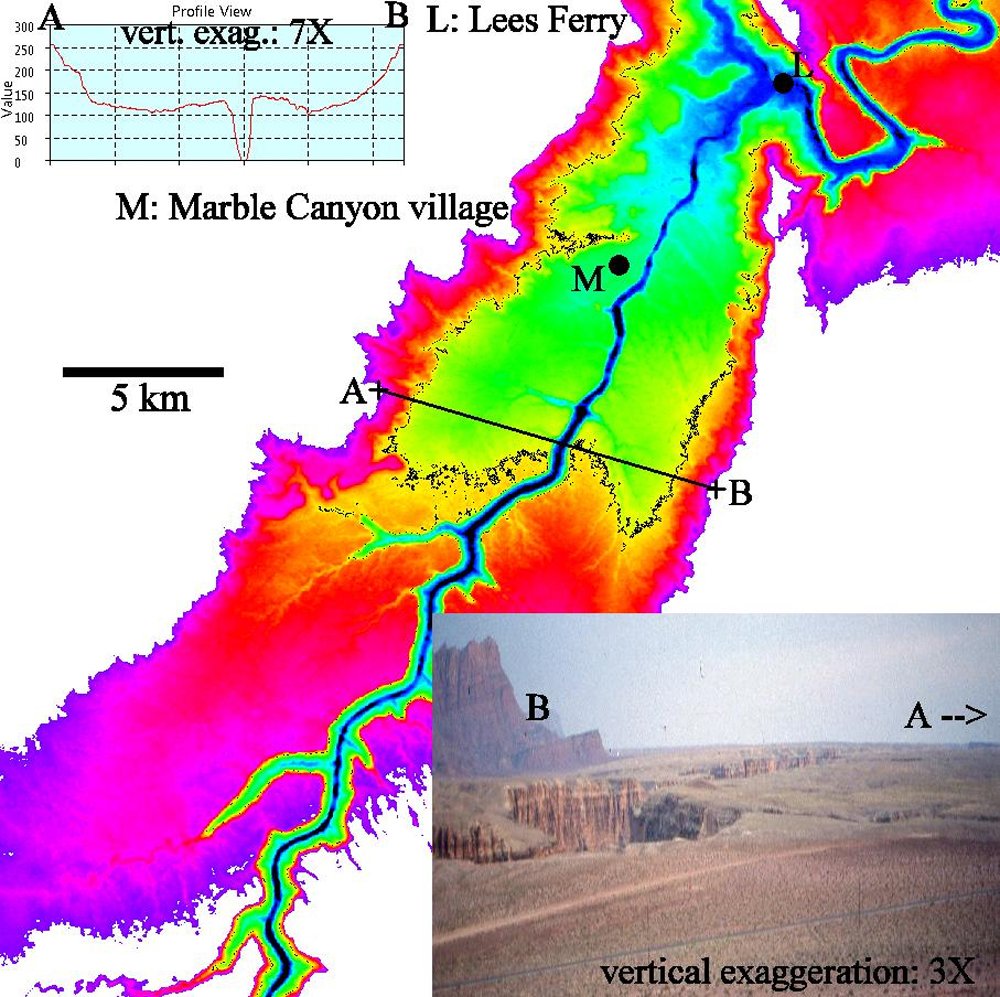

Fig. 10. Observations of Marble Canyon spillway allowed Ed Holroyd to understand a “crack-and-capture hypothesis” for catastrophic drainage of a big Utah lake. Note that the axis of the channel marks the crest of the arch structure. Inset Ektachrome photo was acquired by Holroyd on the talus-strewn slope above Marble Canyon village during field work on July 14, 1987.

Fig. 10 shows the spillway at Marble Canyon and Holroyd’s new understanding of its configuration. Austin describes how Holroyd explained it: “In a December 1987 phone conversation, Ed was excited about his ‘crack-and-capture hypothesis.’ The Colorado River channel at Marble Canyon that Ed observed in July 1987 was oriented down the axis of an uplifted arch structure just like the channel at the upstream end of Black Canyon of the Gunnison River that he observed in 1985 and 1986. I told Ed that I liked the way he was thinking about spillover at Lees Ferry into Marble Canyon and mentioned that a geology graduate student might want to do a research thesis on such a topic. I encouraged Ed to submit a written proposal so that a student can easily explore the idea. I requested that the proposal contain a clear and positive hypothesis that a student might test.”

The three-page proposal was titled, “Some Research Opportunities at Marble Canyon for Creationists (written January 1988 from observations in July 1987)” which Austin received with Holroyd’s cover letter dated January 24, 1988.16 Holroyd’s thesis proposal includes, “. . . the existence of Lake Bidahochi means that there were similar ‘Great Lakes’ throughout the entire Four Corners region and into Wyoming . . . . When one stands on the hillside north of the Marble Canyon Lodge and looks southwest over the valley containing the Colorado River, the doming of the strata is obvious. The Colorado River has chosen a bed in the crest of an anticline. Rivers naturally chose lower rather than higher ground for their beds. This means that the top of the anticline developed a crack which captured the Colorado River . . . . the channel was dug by the process of cavitation resulting from the catastrophic release of water from a large lake upstream through that crack . . . . Perhaps the catastrophic release of three Great Lakes-worth of water carved the Grand Canyon in a few weeks by means of cavitation process rather than in millions of years.” Holroyd’s perspective of Marble Canyon drainage spillway after the December 1987 phone conversation might be best portrayed by an oblique view above Lees Ferry Spillover (fig. 11).

Fig. 11. Oblique aerial view of Marble Canyon Spillway from just above Lees Ferry Spillover. The view is toward the southwest. Field work in July 1987 allowed Ed Holroyd to propose that Lees Ferry Spillover was the overflow location of a dam of the “big Utah lake.” Later, Brown (1989) also favored Lees Ferry being a drainage spillway. Image rendered by Ed Holroyd using Google Earth software.

Where Are the Lake Deposits?

If an enormous lake breached a natural topographic dam through the east side of the Kaibab Upwarp, one would expect to find evidence in sediment diagnostic of such a lake. Quiet lake water traps wind-blown silt and clay, and the dissolved minerals in the water could precipitate calcium carbonate particles to form a type of limestone called tufa. Austin recalls, “The quiet water of a lake could allow accumulation of clay and calcium carbonate particles just east of Grand Canyon. If such sediment layers exist, it would be like court-room reports of a smoking gun at the scene of a crime.” Austin further describes his thinking, “In 1987 we were suggesting that late-Flood and post-Flood uplift of the Colorado Plateau trapped water in the saucer-shaped depression on top of the Colorado Plateau. It would be a lake formed after the Global Flood of Noah’s day but just as the Ice Age began. Kaibab Upwarp is the key topographic barrier to retain a lake in northeastern Arizona as the lake map attempts to depict. If the early post-Flood Hopi Lake existed just above 6,000 ft elevation in Arizona, then its presence would likely obligate a huge lake or lakes in Utah and Colorado.”

For several years Austin had been searching for silt and limestone deposits that might be critical evidence that Hopi Lake stood just above 6,000 ft elevation on the east side of Kaibab Upwarp. Austin studied calcium carbonate deposits in the Cape Solitude area on Navajo lands just east of Grand Canyon and other deposits adjacent to Blue Moon Bench (see fig. 4). These deposits resemble the shoreline lake limestone called tufa. Robert Scarborough, a geologist who conducted graduate research on the Hopi Buttes silt, agreed with Austin. Scarborough had also been looking for ancient lake sediment east of Grand Canyon. Together, in 1988, they affirmed privately that ancient Hopi Lake was impounded just east of the Kaibab Upwarp, and that spillover of that lake likely eroded Grand Canyon.17

Spillway at Mount St. Helens

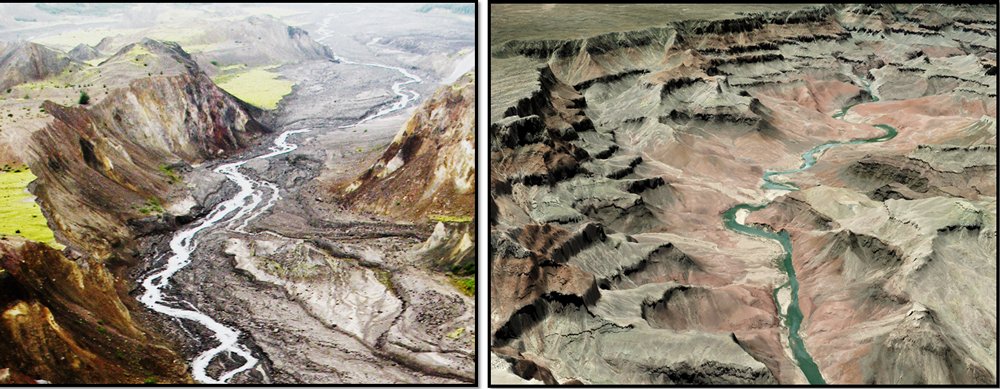

What would the spillway look like if lakes catastrophically drained by spillover through the highlands of northern Arizona? That was a vital question that geologists were asking 30 years ago. Austin recalls, “The largest landslide deposit in human history has a volume of two-thirds cubic mile and occupies an area of 23 mi2 on the north side of Mount St. Helens. That historic-record debris deposit formed as the volcano exploded on the morning of May 18, 1980. Since then, Mount St. Helens volcano has provided a laboratory for the study of catastrophic erosion. I started doing field work on spillover erosion at Mount St. Helens in 1983. I described in public lectures and in publications how the mudflow on March 19, 1982 breached the landslide debris north of the volcano, especially an elevated landslide debris dam. The breach was not straight through the debris dam but has a curving-to-the-right path. In significant ways the spillway of the breached dam at the volcano resembles the spillway below No Name Point in eastern Grand Canyon.” Austin pointed out in publications similarities as early as 198418 and later published in peer-reviewed geology publication a description of the “Little Grand Canyon” in association with the breached landslide debris dam (Austin 2009). When observed just downstream of their points of spillover (see fig. 12), both landscapes are characterized by U-shaped canyon cross-sections, modern meandering channels, amphitheater-headed alcoves, steep cliffs and elevated upland flats. The unbranched mud spillway just downstream of the breached explosion pit at Mount St. Helens is very similar to the unbranched eastern Grand Canyon through the Kaibab Upwarp.

Fig. 12. Spillways at Mount St. Helens (left) and Grand Canyon (right). Both images are views from above their spillover points looking downstream. Mount St. Helens spillway (left) is on the North Fork of the Toutle River and is eroded by spillover 180 ft deep through unstratified May 18, 1980 debris avalanche deposit by mudflow of March 19, 1982. Grand Canyon spillway (right) is just downstream of the breach in the margin of Hopi Lake and is 4,500 ft deep eroded by water through distinctly stratified sandstone, shale and limestone to form the present channel of the Colorado River. These landscapes, just downstream of their points of spillover, are characterized by U-shaped canyon cross-sections, modern meandering channels, amphitheater-headed alcoves, very steep cliffs, and elevated upland flats. Grand Canyon spillway (right) has No Name Point in upper center. Grand Canyon spillway is 25 times deeper than the Mount St. Helens spillway. Photos copyright Steven A. Austin 2019.

As early as 1984 Austin was pointing out that there is much more to the correspondence between Mount St. Helens and Grand Canyon than just the unbranched spillways of these breached dams. As early as 1984, Austin called attention to three erosional areas at Mount St. Helens: (1) the breached dam and its prominent unbranched spillway, (2) the downcut landscape above the breached dam with its distinctive rill-and-gully topography, and (3) the drainage-dissected landscape with prominent tributary canyons downstream of the spillway. Upstream of the breached topography at Mount St. Helens is the large basin with 700 m long steam-explosion pit where mud pooled temporarily behind the barrier. After breaching, that upper basin has been downcut a depth of 100 ft (30 m) displaying new channels with fluting and rill-and-gully erosion. Those oversteepened channels and heightened topography in the upper basin at Mount St. Helens resemble some of the “canyonland topography” in Marble Canyon and Glen Canyon areas on the upper Colorado River. Also, downstream of the unbranched spillway at Mount St. Helens is the region where multiple side canyons enter the North Fork of the new upper Toutle River (Austin 2009). These downstream tributary drainages also appear to be related to the main mudflow breaching event in March 1982. In the upper left corner of fig. 12 (left), a large side canyon joins the channel just below the spillway (Scheele 2010).19 These big side canyons at Mount St. Helens are similar to Kanab Creek and Havasu Creek (see fig. 4) in the central Grand Canyon.20 Thus, some unanticipated similarities relate historic spillover erosion at Mount St. Helens to Grand Canyon. That would be expected if spillover is a good working hypothesis.

The Forgotten “Grand Canyon” of the Mojave Desert

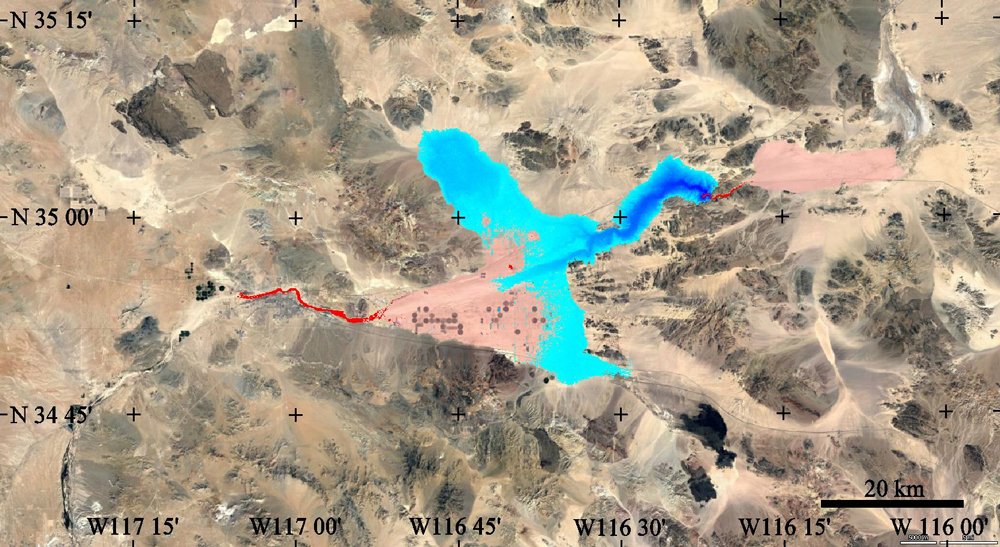

An awkward moment occurred in the summer of 1930 at Stanford University in California. Dr. Eliot Blackwelder, chairman of the Geology Department, was opening graduate school, but where was that new geology student named Elmer Ellsworth? When 23-years-old Ellsworth showed up late to school, he appeared to have an adequate geologic excuse. As he crossed the country in his Model A Ford from Wisconsin, he detoured to Grand Canyon. His mule train caused him to be delayed within Grand Canyon! (Ellsworth 1999).21 Ellsworth’s uneasy start at Stanford was soon forgotten when he explained to his new professor how his graduate work at University of Wisconsin had revealed sedimentary evidence of an Ice Age lake in central Wisconsin. That’s when Eliot Blackwelder recognized he had, contrary to first impression, a promising student that could do his Ph.D. dissertation study on an ancient Ice Age lake in Mojave Desert of Southern California. As Blackwelder described his spillover hypothesis for the entire Colorado River drainage basin, his new student recognized that the hypothesis could be tested at ancient Lake Manix and Afton Canyon on the Mojave River (Afton Canyon located in fig.3, with Lake Manix reconstructed in fig. 13). Lake Manix had three prominent basins: (1) Coyote Basin on the northwest, (2) Troy Basin on the south, and (3) Afton Basin on the northeast.22 Over the next two years Ellsworth carefully mapped the Ice Age lake’s sediments, interpreted the lake’s history, and turned in his Ph.D. dissertation, on time (Ellsworth 1932). Elmer Ellsworth made his professor proud! In 1936 the student and his professor coauthored a short description of their discovery in a peer-reviewed geology journal (Blackwelder and Ellsworth 1936).

Fig. 13. Mojave River drainage east of the city of Barstow, in San Bernardino County, California. Ice Age Lake Manix (elevation 543m) breached its dam at Afton Canyon, eroded its spillway, and deposited outwash eastward (downstream) in Soda Lake basin. Shades of blue depict ancient Lake Manix. Deepest eastern arm of Lake Manix is Afton Basin where deepest erosion is evident. Red depicts Mojave River bedrock canyons, with short red segment directly east of deep Afton Basin being the famous Afton Canyon spillway. Semi-transparent pink shades depict braided delta deposits. (Map drawn by Ed Holroyd from DEM onto satellite image base with the specified elevation and spillover of Lake Manix.

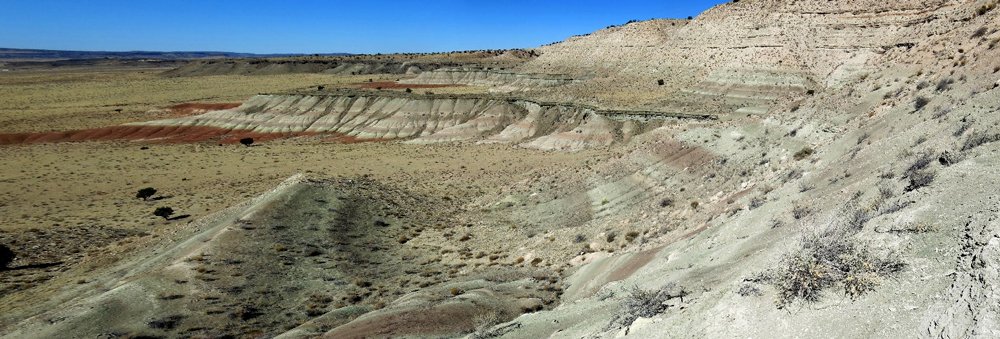

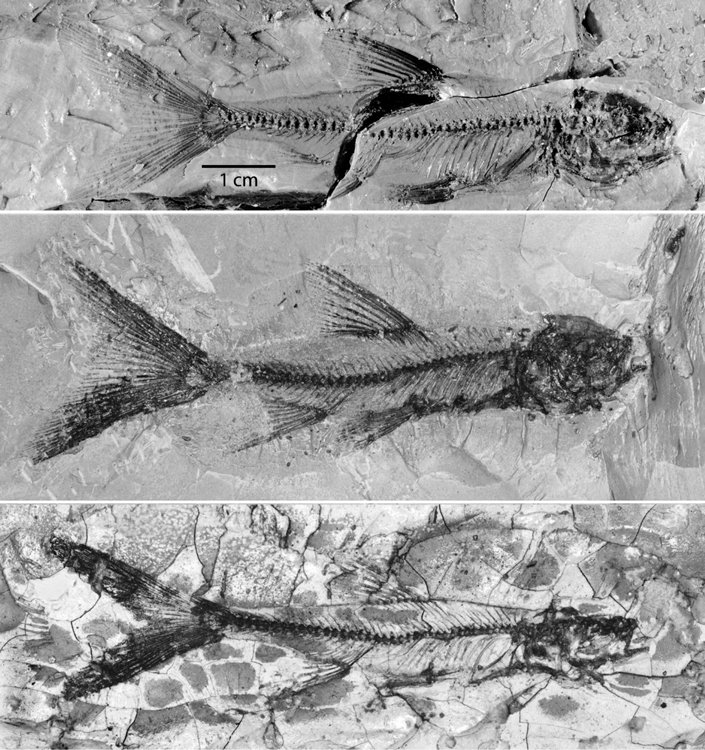

In the 1930s elevation control and topographic contour were much less accurate than today’s data sets. So, in retelling the Lake Manix story, we use here newer and improved topographic control. Ellsworth believed that the lake shore was at elevation 1,781 ft (543 m). The surface area of Ice Age Lake Manix was almost 90 square miles, and the lake volume was about three-quarters cubic mile. Ellsworth used shoreline and lake-bed evidence to understand that the lake drained catastrophically by spillover. Greatly enlarged by flood erosion, Afton Canyon is now 440 ft deeper providing a new channel for Mojave River eastward through a mountain into Soda Lake basin. The uppermost one mile of the four-mile-long spillway (fig. 14) is eroded about 440 ft deep through bedrock within Afton Canyon. A major part of that deepening, according to Ellsworth, occurred because of spillover. The lower half of Afton Canyon (fig. 15) when viewed toward the east is less imposing. The arm of Lake Manix immediately adjacent to the breached dam is called Afton Basin, and it contains alluvial deposits, especially conglomerates, now deeply channeled (figs. 16 and 17). Erosional landforms within Afton Basin have been referred to as “canyonland topography” (Meek 2019)23 that resembles, both in appearance and variety, landforms upstream of Grand Canyon on the Colorado River. Afton Basin, remarkably, lacks fine-grained lake deposits.24 Those Afton Basin erosional landforms resemble those in the upper Colorado River drainage basin, but are roughly at one-tenth scale. By 1936 it seemed like spillover was a good working hypothesis that could stand on its own!

Fig. 14. Afton Canyon looking westward into the topographic basin of ancient Lake Manix. Eliot Blackwelder and Elmer Ellsworth in 1936 understood Afton Canyon to be the spillway from catastrophic drainage of Lake Manix. Here the spillway was eroded through bedrock to a final depth of 440ft. That makes Afton Canyon a one-tenth scale example relevant to the Grand Canyon debate. Union Pacific Railroad tracks are on the north side of the canyon. Photo by QT Luong, terragalleria.com, copyright 2019. Used by permission.

Fig. 15. Downstream end of Afton Canyon looking east. Catastrophic drainage of Lake Manix downcut the extreme east end of Afton Canyon, with the canyon dying out abruptly into the next downstream basin. In the canyon’s place downstream is an enormous outwash plain of flood debris entering Soda Lake basin near Baker, California. Photo by QT Luong, terragalleria. com, copyright 2019. Used by permission.

Fig. 16. View of Afton Basin from above the spillover point of Afton Canyon looking upstream (west) into the dissected bed of ancient Lake Manix. Several geologists have used the term “canyonland topography” to describe the unique assortment of flood erosion landforms in the old bed of Lake Manix. Drainage of Lake Manix occurred through the spillway in foreground. Photo by QT Luong, terragalleria.com, copyright 2018. Used by permission.

Fig. 17. Erosion in Afton Basin, just upstream of the breached dam at Afton Canyon. This “canyonland topography” was eroded in conglomerate of the bed of the Lake Manix during and after the flood’s drainage. Stream channel in front left is about 8 ft wide. Photo by QT Luong, terragalleria.com, copyright 2019. Used by permission.

The 1930s were not the best time to publish the lake overflow explanation for erosion of Afton Canyon. Ellsworth could not be employed by academic institutions because of the Great Depression, and, so, he went to work for the petroleum industry. Then, World War II came and Ellsworth joined the Air Force. Blackwelder had other projects with students demanding attention at Stanford. He personally was dealing with health issues, and other geologists seemed preoccupied in telling elaborate stories about headward erosion of Grand Canyon. For the next 50 years little was said about Mojave River spillover. It was virtually ignored. Then, in the late 1980s a geology graduate student named Norman Meek at University of California Los Angeles revisited the evidence for Lake Manix. Meek said he was “shocked” to discover that spillover had been so well stated by Blackwelder and Ellsworth 50 years before, and he said he was greatly concerned as to why it had been virtually “forgotten.” Meek started publishing on Lake Manix and Afton Canyon (Meek 1989). He became a crusader for spillover. Three lines of evidence from Lake Manix promoted spillover: (1) the abrupt disappearance of the lake from its highstand elevation, (2) the Afton Canyon spillway and its upstream dissected “canyonland,” and (3) the thick and coarse buried flood sediment layer encountered in water wells downstream of Afton Canyon. In 1990 Meek completed his doctoral thesis on Lake Manix (Meek 1990).25

The Afton Canyon Controversy

One might suppose that the rediscovery of the spillover hypothesis for Afton Canyon would now be received eagerly by the geology establishment. After all, the establishment should be seeking to assemble pieces of a great puzzle to solve important problems like erosion of Grand Canyon. Add to that, two doctoral dissertations supported the hypothesis. Instead, rebuttal papers were written to dispute spillover in the Mojave River drainage basin (Enzel, Wells and Lancaster 2003; Wells and Enzel 1994; Wells et al. 2003). Three authors argued that the bedrock obstruction at Afton Canyon was eroded much more slowly from the east by an upstream migrating gully, not very much by an overtopping lake from the west (Enzel, Wells, and Lancaster 2003). The lake, according to spillover critics dried up slowly, leaving behind a progressive series of lower shorelines as Lake Manix finally disappeared. However, critics did not give specific locations of those recessional shorelines. Somebody asked the question: could they be arguing just from elevation measurement errors?

As the twenty-first century began, Lake Manix’s history became embroiled in heated discussions which could be called the “Afton Canyon Controversy.” An initial report by U.S. Geological Survey attempted to avoid the strong disagreements (Reheis and Redwine 2008). U.S. Geological Survey became available to conduct extremely detailed remapping in Afton Basin, the eastern bed of the big lake (Reheis et al. 2014). USGS used differential corrected GPS and LiDAR to measure shoreline elevations with errors less than one meter. After remapping by USGS, Lake Manix’s history was “. . . punctuated by tectonic movements and a catastrophic flood that reconfigured the lake basin” (Reheis et al. 2014, 1). USGS had independently confirmed the Blackwelder, Ellsworth and Meek version of spillover! Critics appeared to be rebuffed. Then, the critics received criticism. Afton Canyon spillover critics are described as having a flawed method of educating geologists. This rebuttal unveils “a pedagogically engrained bias,” and reveals, “. . . the continued omission of spillover as a possible transverse drainage hypothesis hints at a larger problem related to selective textbook content and a constrained paradigm that does not inform adequately about fundamental river development mechanisms” (Hilgendorf et al. 2020). That’s fancy academic language describing educational bias. Is “Afton Canyon Controversy” an episode to inform us about bias one encounters in the much larger “Grand Debate” concerning erosion of Grand Canyon?

Take a Look at My Backyard!

Four geologists open their 2009 geomorphology research paper with the thought-provoking sentence, “The study of how rivers cross obstructing mountains, once popular in the early twentieth century, has seen a dramatic resurgence in the last decade” (Douglass et al. 2009). Researchers had worked out a technical “checklist” or “logic tree” for understanding rivers that cross mountains (Larson et al. 2017).26 Once the options and methodology were stated technically, many of these scientists deliberately attempted to generate their own applications of “spillover” to landscapes where they were living. An earth scientist speaks about his or her “backyard” with enthusiasm and passion, often speaking with authority, even with a hint of pride. This emphasis on the geology of where the earth scientist lives has been called the “backyard effect.”

It is easy to see the “backyard effect” in our story of Grand Canyon erosion. Remember that Ed Holroyd was living in Montrose, Colorado when he became fascinated by the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River. Then, he applied his thinking from the Gunnison River to the Grand Canyon spillover erosion problem. Another noteworthy “backyard” example is Dr. Norman Meek. He rediscovered catastrophic drainage of ancient Lake Manix explains erosion of Afton Canyon running through mountains along Mojave River (just northeast of his home in San Bernardino, California) (Meek 1989). Similarly, cooperation among eight researchers (Larson et al. 2014)27 promoted understanding that lake overflow of Pemberton Basin established the modern course of the Salt and Verde rivers (north and east of their homes in Phoenix, Arizona). Of those eight Arizona researchers, only Phillip Larson was not living in Arizona at the time of publication. Larson had moved from the desert landscape of Phoenix back to his original home in the glacial landscape of Minnesota, where he found long-appreciated evidence of “spillover in glacial/proglacial environments” (Hilgendorf et al. 2020, 9–12). Many other earth scientist examples of the “backyard effect” could be cited.

Reviving the “Grand Debate”

The forgotten transverse drainage hypothesis was proving itself, especially by the backyard effect, in technical thought and literature to have explanatory power! Then, an interesting chain of events happened. Lake spillover thinking transferred (would “overflowed” be a better word?) from technical science journals to Internet news releases, and finally, to television documentaries. A 2012 Internet news release described Grand Canyon erosion with the lake-carved-the-Canyon theory as, “A favored concept for two decades” (Oskin 2012). The 2008 National Geographic made-for-TV documentary “Grand Canyon Spill-Over Theory” features Dr. John Douglass and his stream table experiment at scale 1:60,000 that modeled Grand Canyon’s overspilling lake.28 A second stream table experiment of lake spillover by Douglass appears in the History Channel made-for-TV documentary “How the Earth Was Made—Grand Canyon” (2009, season 2, episode 1).29 Detailed parameters of the spillover of Hopi Lake are proposed in two papers published by Douglass (Douglass 2011; Meek and Douglass 2001). These discussions of spillover hypothesis feature Hopi Lake (aka “Lake Bidahochi”) as the primary cause of the erosion that made Grand Canyon. As noted by geologists Jon Spencer and Philip Pearthree, spillover discussions come naturally because geologic features in the Grand Canyon region seem compatible, whereas the alternate hypothesis of headward erosion and stream capture remain difficult to visualize (Spencer and Pearthree 2001).

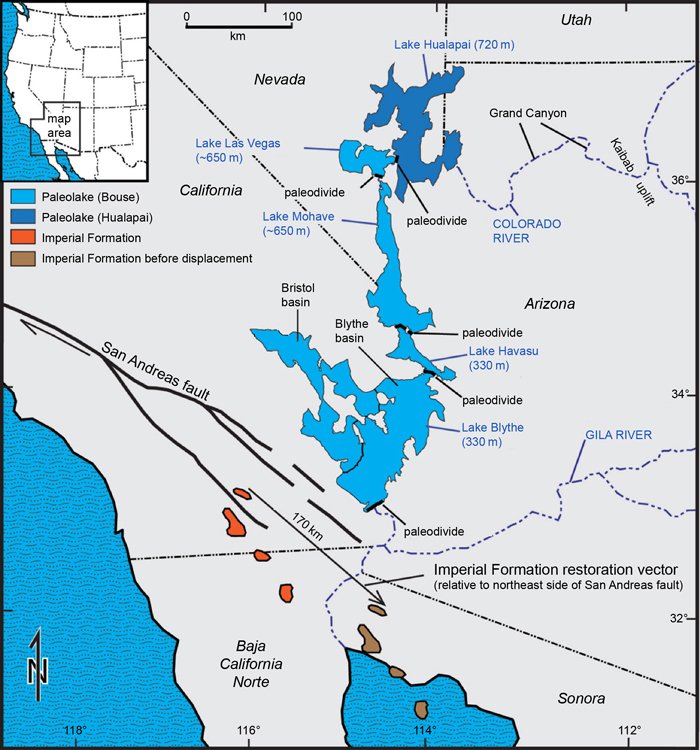

Fig. 18. Lake system downstream of Grand Canyon indicated by tufa deposits of the Bouse Formation according to the fill-and-spill hypothesis of Jon Spencer and his coworkers. Also shown are the marine delta deposits of the Imperial Formation associated with abrupt appearance of the Lower Colorado River according to Rebecca Dorsey and her coworkers. Basins with paleodivides were likely breached from north to south by progressive filling and spill of lakes that established the channel of the Lower Colorado River. Therefore, the lakes did not all appear at the same time. Map is a modified version published by Jon Spencer (Arizona Geology Magazine, December 2011).

Dr. Jon Spencer and his coworkers feature catastrophic lake spillover prominently in explanation of the Lower Colorado River (Spencer et al. 2013). They propose that downstream of Grand Canyon was an almost continuous chain of five or six basins with five lakes—Lake Hualapai, Lake Las Vegas, Lake Mohave, Lake Havasu, and Lake Blythe (fig. 18). These Lower Colorado basins with lakes were supposed to have filled behind and spilled over natural bedrock dams. Freshwater lake evidence is noted from tufa layers in the Pliocene Bouse Formation along the descending stairway of basins and lakes that later formed the path for the Lower Colorado River (Spencer et al. 2013).30 Lake sediment and fossils in the Blythe Basin just north of Yuma, Arizona indicates the abrupt Pliocene entry of the Colorado River (Bright et al. 2016). The entry of the Colorado River near the town of Blythe is marked by the appearance of green claystone. Discovery of multiple spillover events on the Lower Colorado River lead, by association, to consideration of the same process upstream of Grand Canyon (e.g., Bidahochi Basin) (House 2008, House, Pearthree and Perkins 2008).31

A final puzzle piece that remains to be integrated within the Grand Canyon spillover story is the ancient marine delta of the Colorado River. Dr. Rebecca Dorsey, geologist at University of Oregon, and her coworkers favor catastrophic spillover, pointing out that the Colorado River sediment appears very abruptly and recently within the marine mudstone of the Imperial Formation (Pliocene) in Southern California (Dorsey et al 2018). Here green claystone also marks the rapid influx of river water.

A Very Polite Description of the Last Thirty Years

Let’s go back to the year 1988 and remember three important events that prepared the way for spillover discussions during the last 30 years. First, creationists in 1988 were exploring configuration of ancient Colorado Plateau lakes and their possible points of spillover. Austin was working on the “tectonic tilting hypothesis” for the configuration of Kaibab Upwarp at the time of overflow of Hopi Lake. Holroyd surveyed the upper Colorado River drainage basin and located “Cimarron Spillover” and “Lees Ferry Spillover.” Second, the mud deposits of the Bidahochi Formation were being appreciated with the overall basin geometry of the Colorado Plateau as evidence of a very big lake east of Grand Canyon. Bob Scarborough in 1988 had composed his manuscript “Cenozoic Erosion and Sedimentation in Arizona” that was ready for timely publication in 1989 (Scarborough 1989). Third, also in 1988, Afton Canyon on the Mojave River in Southern California was “rediscovered” as a landscape model for spillover. Meek was ready to publish his 1989 paper detailing the breaching process and the implication that it has wide application to landscapes.32 In 1988 the spillover hypothesis was beginning as a small trickle of water but was soon to become a torrent!

How has thinking about erosion of Grand Canyon progressed during the last 30 years, since that lecture on the Canyon rim in 1988, since better appreciation of Arizona’s lake mud deposits in 1988, and since the rediscovery of Afton Canyon spillway in 1988? Grand Canyon ranger and geologist Wayne Ranney writes, “So the twentieth century closed without a widely accepted theory on Grand Canyon’s origin” (Ranney 2012, 97). That’s Ranney’s very polite way of saying the ancestral Colorado River did not carve Grand Canyon over tens of millions of years (the former century’s National Park consensus ranger explanation). Ranney is also affirming, very politely, that a replacement theory among geologists has not been generally accepted. In less complementary words, one could say that chaos prevails in geologists’ thinking about erosion of Grand Canyon! As the twenty-first century began, Ranney adds, “. . . spillover theory was nudged to the forefront of ideas regarding the origin of the Colorado River” (Ranney 2012, 103).

Progress in Creationist Modeling

So, these “fill and spill” ideas have proven beneficial and timely for geology. During the last thirty years creationists have continued to develop the idea of a breached dam at the eastern Grand Canyon. Austin published in 1994 a map of lakes and description of the Bidahochi Formation with a defense of the breached dam hypothesis for erosion of Grand Canyon (Austin 1994). The global flood made strata of Grand Canyon, the retreat of flood waters beveled the plateau surface, and the structural dam breached in the post-Flood period. Austin favored the initial breach of Kaibab Upwarp at the northwestern margin of Hopi Lake. Also, Austin (2009) published a description in conventional geology literature of the catastrophically eroded landscape on the north slope of Mount St. Helens with a geologic map showing the breached dam and “Little Grand Canyon.” That’s where he described major side canyons associated with the main breach. The comparison of Mount St. Helens to Grand Canyon continues to be significant (see fig. 12).33 Austin carried on study of breached dams, especially the Santa Cruz River breached dam and giant drained lake in southern Argentina (Austin and Strelin 2011).34 That Argentina breached dam is just upstream of “Camp Darwin” where young Charles Darwin wrote in April 1834 his journal explaining why he was adopting Charles Lyell’s ideas of slow river canyon erosion.

Dr. Holroyd after 1988 went on to publish his thinking about the ancient big lakes on the Colorado Plateau and how they affected landforms. Many cliffs on the Colorado Plateau studied by Holroyd failed to confirm uniformitarian ideas about boulder aging leading to the term “missing talus” (Holroyd 1987; 1990b). Holroyd states: “Many of us have indelible images in our minds of the red mudstone Moenkopi Formation slopes at Lees Ferry with missing talus. Many of us believe Lees Ferry is an ancient spillway for catastrophic drainage of a big lake.” Slope analysis of the Colorado Plateau performed by Holroyd (1994) seems to locate possible shorelines that could have been steepened by wave erosion or spring sapping at the edge of lakes. Although computer technology has much improved in the last 30 years, Holroyd’s work shows very early sophistication.

In 1989 Dr. Walter Brown further developed the breached dam hypothesis proposing that a big lake in Utah (he called “Grand Lake”) was the essential trigger agent in eroding Grand Canyon (Brown 2008).35 Brown’s view is that Grand Lake first overtopped its southern barrier (Lees Ferry at Marble Canyon) at elevation of 5,700 ft. Brown supposed that the big Utah lake drained southward into Hopi Lake causing uplift on the Kaibab Upwarp and breaching of Hopi Lake through southern Kaibab Upwarp. In following years creationists reviewed various breach dam proposals and their evidences (Oard 1993; Williams, Meyers and Wolfrom 1992).