The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

The Rwandan genocide of April–July 1994 shows how a single group of people living next door to each other, speaking one language and sharing the same culture, even often intermarrying, were artificially divided into two races by colonial rulers infused with Darwinism. The race judged superior was the Tutsi race, and that judged inferior was the Hutu race. In the end, in one of the worst genocides of the last century, over 800,000 Rwandans were murdered, mostly the Tutsi murdered by the Hutus.

This is one more example of the harm that results from rejecting the biblical teaching that all humans are descendants of Adam and Eve, and replacing this belief with Darwinism. But “Creationism would only be challenged in the second half of the 19th century after the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species” (André 2018, 278). In the century since Darwin, war has led to the murder of close to an estimated one billion innocent people (Courtois et al. 1999).

Keywords: social Darwinism; Rwanda genocide; Hutus, Tutsi; Darwin; genocide; racism; Africa; Adam and Eve; Germany; colonialism; Belgium

Introduction

The two largest ethnic groups in Rwanda are the Hutu and Tutsi. The Hutu make up 85% of the population and the Tutsi a mere 14%. Most of the remaining 1% of the population are Twa (also known as Batwa, the pygmy hunters). Rwanda, a stunningly beautiful country, is located in the eastern part of central Africa (fig. 1). It is about the size of Maryland with a total population of almost ten million for both Rwanda and Burundi, making them the most densely populated nations in Africa.

Fig. 1. The location of the tiny country of Rwanda in south central Africa. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rwanda_in_Africa_%28relief%29_%28special_marker%29_%28-mini_map%29.svg.

Rwanda was first colonized by Germany in 1894 and, after Germany lost World War 1 in 1918, Rwanda came under Belgian rule until the country became independent in 1962. The first colonizers

brought with them their obsession with the classification of human kind according to their race and origin. This Western Pseudo-Science was influenced by the work of Charles Darwin and his theory of evolution. Western settlers [from Europe] saw themselves as culturally superior to the savages they had discovered and were eager to document these three new found races [the Hutu, the Tutsi, and the Twa]. (Millar 2014, 1)

The division, which resulted from the artificial racialization of Hutu and Tutsi in both Rwanda and Burundi, was one legacy of colonization that has produced some of the worst bloody violence existing anywhere in the world. It was only under colonial rule “that the people of Rwanda have classified themselves upon such rigid racial lines. . . . The West has played a leading role in contributing to the prevalence of racism in Rwanda in the last century” (Millar 2014, 1). Colonial rule also converted minor tribal differences into racial categories (Hinton 2003, 5). Before this racialization the various tribal groups largely lived in harmony with each other. They shared the same Bantu language, lived side by side without any Hutuland or Tutsiland, and even often intermarried (Prunier 1995, 5).

Professor Prunier detailed how the German and Belgian intellectuals created the white superior race myth based on Darwinism, and in doing so they did not realize that this new social structure would ultimately lead to so much bloodshed. The hierarchy placed the Tutsi at the top. When the white colonizers were in Rwanda, the Tutsis, as the so-called superior race, had ultimate control over what the Belgian’s saw as a civilizing mission. The social structure put into place in Rwanda cannot be understood outside the context of the West. As powerful as the Tutsi were, or thought they were, after independence the Tutsi remained at the top of the hierarchy supported by the West and Darwinism (Jean 2006, 4) (Prunier 1995).

Supporting this conclusion, some leaders accepted the belief that the Tutsi migrated south from the horn of Africa. As foreigners, they “were somehow a ‘superior race’, and the Rwandans were fundamentally unequal. Some people were born to rule and to exploit, while others were born to obey and serve” (Melvern 2019, 11–12). As Melvern has documented, the idea that Hutu and Tutsi were distinct races “originated with the English . . . [after] 1859, the year that Darwin published On the Origin of Species” (Melvern 2019, 11–12). The German administration during their rule before 1918, were also infused with Darwinism which they used to further divide the people into two main racial groups.

Germany became one of the first nations to be converted to Darwinism and soon spread this worldview to their colonies. As early as 1871 Professor William Preyer wrote to Darwin explaining that “there is no University in Germany where your theory is so openly confessed and publicly taught by so many professors. Häckel, Gegenbaur, Dohrn, Strasburger, W. Müller, myself: we are true Darwinians, in our lectures and writings” (Preyer 1871).

From academia Darwinism rapidly spread throughout Germany and then to their African colonies. After 1918, when the Germans lost the war, they were forced to give up their colonies. The Belgians took over Rwanda and also used not only Darwinism, but other factors, even the long debunked phrenology belief, to infuse racism into Rwanda, which eventually lead to the Rwandan genocide (André 2018). Although this review focused on the importance of Darwinism, as is common in genocide killings, several factors were involved.

Other Important Steps Leading to the Genocide

The Belgian colonizers viewed the Hutu as ignorant, vile, slaves by nature, and lacking ambition. Hutu features were considered ugly and indicative of the inferior Negro. A 1925 colonial report describes the Hutu “race” as “generally short and thick-set with a big head, a jovial expression, a wide nose, and enormous lips” (Twagilimana 2003, 45). The Twa were labeled as being the most primitive of the three racial groups. They were described as “small, chunky, muscular, and very hairy; particularly on the chest. With a monkey-like flat face and a huge nose, he is quite similar to the apes whom he chases in the forest” (Rapport annuel du Territoire de Nyanza 1925, 45 quoted in Twagilimana 2003, 34). The Hutu were further described as “extroverts who like to laugh and lead a simple life” like the apes they resemble.

In contrast to the “intrinsically inferior” Hutu and Twa, the Tutsi received much praise from their Belgian colonizers. During this period of social Darwinism, Belgian colonizers judged the Tutsi as the most evolved ethnic group in appearance and intelligence as well as more closely related to the Europeans than the Hutu, and therefore superior to the Hutu. In fact, the “Europeans were quite smitten with the Tutsi, whom they saw as definitely too fine to be ‘negroes’. Since they were [believed to be] not only physically different from the Hutu but also socially superior, the racially-obsessed, nineteenth-century Europeans started building a variety of hazardous hypotheses on their ‘possible’, ‘probable’ or, as they soon became, ‘indubitable’ origins” (Prunier 1995, 6–7).

The colonial minister in Rwanda was quoted in 1925 as saying that the Tutsi, also called the Batutsi, were of good racial stock that had none of the undesirable traits

of the Negro, apart from his color. He is very tall, 1.8 m at least, [even] . . . 1.9 m or more. He is very thin, a characteristic which tends to be even more noticeable as he gets older. His features are very fine: highbrow, thin nose and fine lips framing beautiful shining teeth. Batutsi women are usually lighter skinned than their husbands, very slender and pretty in their youth, although they tend to thicken with age . . . Gifted with . . . intelligence, the Tutsi displays a refinement of feelings which is rare among primitive people. He is a natural born leader, capable of extreme self-control and calculated goodwill. (Rapport sur de l’administration belge du Ruanda-Urundi 1925, quoted in Twagilimana 2003, 34)

In short, the Belgians believed that Tutsi were supposedly superior to the Hutu primarily because they judged them to look more like the Belgians. Largely on this basis, the Tutsi were chosen by the Belgians to rule over the Hutu (Sinema 2015, 55).

In 1933, the racialization of Rwanda took one very important step in leading to the genocide: the formal establishment of three races from what was formerly one people group. The Belgian administration organized a census utilizing teams of Belgian bureaucrats to classify the entire population either as Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa. Every Rwandan was classified by measuring such traits as their height, the length of their noses, and even the shape of their eyes. This is an example of the “almost obsessive preoccupation with ‘race’ in the late nineteenth-century anthropological thinking, this peculiarity soon led to much theorizing . . . and at times plain fantasising” (Prunier 1995, 5).

The major problem, by far, with the Belgian bureaucrats’ classification, as was also true in Nazi Germany, was for

many Rwandans it was not possible to determine ethnicity on the basis of physical appearance. Rwandans in the South were generally of mixed origin and most Rwandans of mixed origin were classified as Hutu. Yet many people looked typically Tutsi—tall and thin. In the north mixed marriages were rare. Some people were given a Tutsi card because they had more money or possessed the required number of cows (Melvern 2019, 14).

In spite of this problem, when the slaughter began, the “Belgians portrayed the violence as a problem of race between the Hutu and the Tutsi” (Melvern 2019, 17). From April to July 1994, the Hutu massacred over 800,000 Tutsi and their Hutu sympathizers. After reviewing all of the common explanations for the genocide, including economic, political, and social, Prunier concluded that a major factor was the Darwinian worldview due to the Belgian control of Rwanda which divided the native people into groups based on their perception of race.

Belgian Distinctions Ingrained in Hutu Beliefs

The Belgian race distinctions, which were emphasized by the Belgians for decades, in time became firmly ingrained in the Hutu belief system. These beliefs later morphed into jealousy toward the Tutsi and then transformed into rage in 1994. Although other factors were involved in the genocide, this review focuses on the major importance of Darwinian teaching that the Belgian government implanted in the population. One example is the Hutu elite used the idea that another Tutsi invasion of their country might occur as a proactive justification for ethnic cleansing. The ethnic mythology made genocide a fathomable solution. The history of the conflict that caused what amounted to a civil war is, for good reason, often compared to the Nazi Holocaust (Hinton 2003).

History of the Racialization

In Rwanda, the Hutu and the Tutsi were originally social constructs that largely reflected class and community position. The wealthier individuals who owned more cattle were called Tutsi, while those in subservient position or of poorer economic status were defined as Hutu. Minor genetic differences were due to the fact that the Tutsi arrived in this region of Africa later. Nonetheless, in pre-colonial society, the Hutu and Tutsi terms were fluid and, depending on the person’s lot in life, one could gain or lose either status.

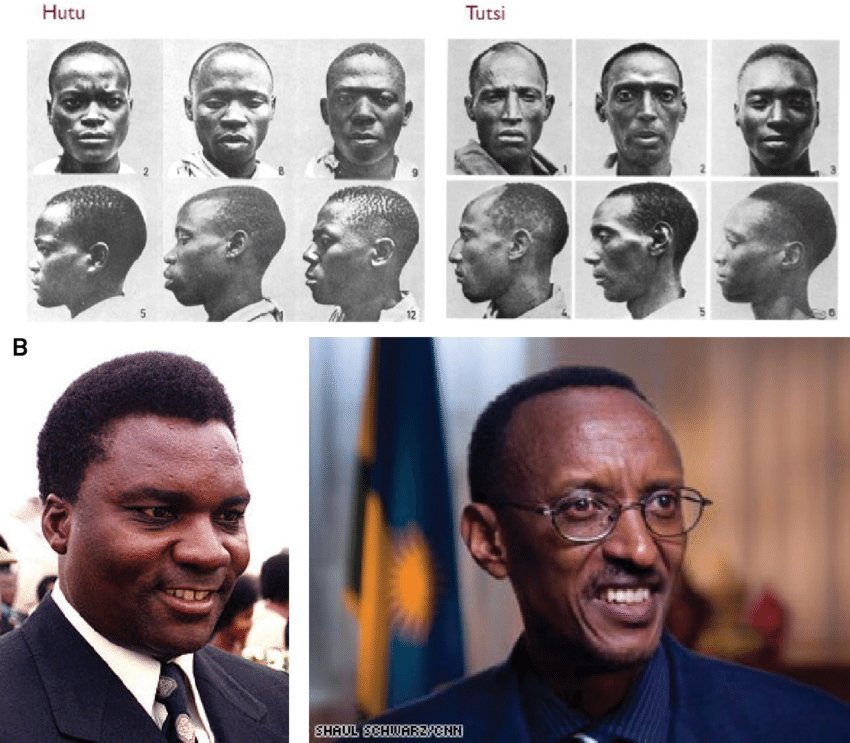

When the Belgian authorities arrived, however, these positions calcified and the complicated nuances of the earlier era were ignored, allowing the pseudoscientific notions of race to take a firm hold on the Rwandan people. The Belgians instituted a permanent, de jure (by right), bifurcation of the groups as racial divisions (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. A chart prepared to identify the Hutu from the Tutsi which reflects the stereotype created by the Westerners. This chart reminds one of the stereotypes used by the Nazis to demean Jews during WWII. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324972132_Phrenology_and_the_Rwandan_Genocide/figures?lo=1.

The fact that “it is frequently difficult to distinguish between Hutu and Tutsi,” required exaggeration of features and looking beyond actual physical differences (Hinton 2003, 212). The question asked was “How could it [the genocide] happen that people, who had shared the history of the same state, and who could be distinguished neither by culture nor language, could behave in such a way?” (Melvern 2019, 21). British philosopher Lord Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) observed that racism created by the colonists in Africa “was the most horrible and systematic extermination of a ‘people’ since the Nazi’s extermination of the Jews” (Melvern 2019, 21). The

most infamous instance of this lethal process of manufacturing difference occurred in Nazi Germany. Drawing on everything from archaeological evidence to theories of race, the Nazis divided the population into a hierarchy of biosocial types with the Aryan race at the peak. Jews, in contrast, were placed at the bottom of the hierarchy and viewed as a dangerous source of contamination. (Hinton 2003, 212)

Likewise, the same lethal process of manufacturing races between people groups occurred in Rwanda. Because in the early decades of Belgian rule, the Europeans favored the Tutsi, most educational opportunities, administrative positions, and economic benefits went to them. This guaranteed resentment on the part of the Hutus.

As the Nazis spoke of Jews as vermin, alien bodies, eternal blood-suckers, parasites, a disease, a plague that threatened to destroy the German state, so also the Hutu spoke of the Tutsi in similar terms, reducing them to sub-humans, including cockroaches and snakes, which made their elimination appear to be critical for the survival of the Hutu (Hinton 2003, 285).

In Kangura, issue 40, the editorial title said it all: “A cockroach cannot bring forth a butterfly.” The editorial argued that the Tutsi, like a cockroach, use the cover of darkness to infiltrate; “the Tutsi camouflages himself to commit crimes.”

This was not just one member of the group. All Tutsi men, women and children were no longer citizens of a nation but cockroaches. In the same way, all Tutsis were gradually associated with being spies of the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF)–Inyenzi–qualifying them as enemies to be killed . . . The killing of more than one million people was . . . carefully planned and executed. The dehumanization was an essential part of it. (Ndahiro 2014)

Although the Rwandan people did not have a specific term for race, when asked about differences between Hutu and Tutsi, most commonly the “respondents cited a physical characteristic such as height or skin color,” the same criteria used to define a race in the West (Straus 2006, 129–130).

The “Christian” Race Theory

Many people in Rwanda, although a Christian nation, rejected the core of Christianity, that all humans are one race, all descendants of the first couple. An early influential European, the English explorer and officer in the British Indian Army, John Hanning Speke (1827–1864) even propounded the Hamitic hypothesis in 1863, in which he proposed that the lighter skinned Tutsi ethnic group were descendants of the biblical figure Ham (Maitland 2010). They had more Hamitic features than the Bantu Hutu over whom they ruled.

Unfortunately, some Christians also accepted the now thoroughly disproved Hamitic race theory and ignored the clear biblical teaching on race (Burrell 2021, 12–14). Speke developed a racial theory to explain the difference between the Hutu and Tutsi and postulated the idea that the Tutsi were a “conquering superior race” based on the Hamitic theory. Speke derived his racist views from a faulty biblical interpretation of the Genesis 9 story of Noah and his son Ham. Ham saw his father drunk and, as a result, God cursed him. Consequently, Ham and his progeny, the Hamites, were cursed with dark skin (Sinema 2015, 55–56). Noah’s other two sons’ progeny, however, the theory teaches, were to father the Aryan and Semite races.

Summary

The “Belgians created a race distinction between two peoples where none had previously existed. Speke’s race theory in action forty years later led to a manufactured race struggle” (Sinema 2015, 73). The end result of replacing the biblical teaching on race with the Darwinian view was a genocide that cost 800,000 lives. How two races were created from one people group that shared the same culture, language, and often intermarried, is a lesson on how an idea can become a divisive legality, at least in the minds of the population. Nonetheless, the existing culture set the stage for the racism that resulted in the Rwanda genocide:

European rule did not invent the terms Hutu and Tutsi, but the colonial intervention changed what the categories meant and how they mattered . . . In the Rwandan Tutsis, the European explorers and missionaries believed that they had found a “superior” “race” of “natural-born rulers.” Europeans wrote that the Tutsi had . . . come to dominate the more lowly Hutus, which the Europeans considered an inferior “race” of Bantu “negroids.” This conception of Rwandan society reflected the anthropological ideas of the day, in particular the so-called “Hamitic Hypothesis,” which saw civilization in Africa as the product of “Caucasoid” (white-like) Hamitic peoples. (Straus 2006, 20)

In the end, race was one of the most important factors in the Rwandan genocide. This is illustrated by the fact that “Rwandan’s national identity cards listed whether each cardholder was a Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa,” solidifying a racial identity in the minds of each card carrier, who were mostly adults (Straus 2006, 225). Also critical was the following: the idea that the Tutsi were racially superior and the Hutu were racially “inferior . . . became an accepted ‘scientific’ truth during colonial times” (Prunier 1995, 11).

References

André, Charles. 2018. “Phrenology and the Rwandan Genocide.” Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 76, no. 4 (April): 277–282.

Burrell, Kevin. 2021. “Slavery, the Hebrew Bible and the Development of Racial Theories in the Nineteenth Century.” Religions (Special Issue: The Hebrew Bible, Race, and Racism) 12, no. 9 (September): 742.

Courtois, Stephane, Nicolas Werth, Jean-Louis Panne, Andrzej Paczkowski, Karel Bartosek, and Jean-Louis Margolin. 1999. The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. See also List of Wars by Death Toll; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_wars_by_death_toll.

Hinton, Aexander Laban. 2003. Why Did They Kill? Cambodia in the Shadow of Genocide, 2, 5, 22, 23–24, 26, 29, 178, 212, 282, 283, and 285. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Jean, Moise. 2006. “The Rwandan Genocide: The True Motivations for Mass Killings.” Atlanta, Georgia: Emory University. http://history.emory.edu/home/documents/endeavors/volume1/Moises.pdf.

Maitland, Alexander. 2010. Speke: And the Discovery of the Source of the Nile. London, England: Faber and Faber.

Melvern, Linda. 2019. A People Betrayed: The Role of the West in Rwanda’s Genocide. New York, New York: Zed Books.

Millar, Henry. 2014. “Racism in Rwanda.” https://cers.leeds.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/97/2015/01/Racism-in-Rwanda.pdf.

Ministère des Colonies. 1921–1961. Rapport sur de l’administration belge du Ruanda-Urundi, 1925. Bruxelles, Belgium.

Ministère des Colonies. 1925. Rapport annuel du Territoire de Nyanza. Bruxelles, Belgium.

Ndahiro, Kennedy. 2014. “Dehumanization: How Tutsis Were Reduced to Cockroaches, Snakes to be Killed.” The New Times. March 13. https://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/73836.

Preyer, William. 1871. “Letter no. 772.1.” In Darwin Correspondence Project. Letter to Charles Darwin, dated April 27, 1871. https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/DCP-LETT-7721.xml.

Prunier, Gérard. 1995. The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide. New York, New York: Columbia University Press.

Sinema, Kyrsten. 2015. Who Must Die in Rwanda’s Genocide?: The State of Exception Realized. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Straus, Scott. 2006. The Order of Genocide: Race, Power, and War in Rwanda. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Twagilimana, Aimable. 2003. The Debris of Ham: Ethnicity, Regionalism, and the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America.