The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

Determining when Jericho was overthrown by Joshua’s army is significant because it not only supports the date of the Exodus, but it also dates the conquest of Canaan. This date must also synchronize with the destruction of Ai and Hazor, two Canaanite cities destroyed at about the same time. Biblical archaeologists have disagreed over which Jericho wall fell for Joshua, and which was the later wall built by Hiel in the time of Ahab. In this paper it will be shown that Joshua’s wall was the one destroyed at the end of the Early Bronze IIIB period and Hiel’s wall dates to the Middle Bronze I. In addition, the great Middle Bronze II–III embankment fortification that is widely and erroneously considered to be Joshua’s wall was built sometime after Hiel’s wall. Some scholars have pointed to the wrong Jericho walls because they do not recognize divergence of the biblical and standard timelines, or they disregard factors such as culture changes before and after Joshua’s destruction. Others do not recognize the authority of the Bible, but express doubt that Joshua’s conquest of Jericho ever happened at all; their conventional dating of the event is usually the reason for this disbelief.

Introduction

Forty years after their dramatic exodus from Egypt, the Children of Israel finally crossed the Jordan River into the Promised Land of Canaan. The ancient walled city of Jericho lay immediately in their path (see fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Map of Canaan showing Jericho, Ai (et-Tell), Hazor, and el-Hammam. (A. Habermehl 2021).

The major military campaign that the Children of Israel had carried out on the east side of the Jordan River (Numbers 21:21–35) must have struck terror into the hearts of all the inhabitants of Canaan. Indeed, this is what Rahab of Jericho told the two spies sent by Joshua (Joshua 2:9–11).

The story of Jericho’s conquest in Joshua 6 is well known. According to the biblical narrative, God caused the fortification wall1 to fall flat (Joshua 6:20), allowing Joshua’s forces to mount straight up into the city from all around. They had been ordered to save Rahab, her family and their belongings, kill all other inhabitants and their animals, and then destroy the city by fire (Joshua 6:21, 24). Bible believers consider that this event actually happened. If so, the ruins of ancient Jericho, today called Tell es-Sultan by archaeologists (Kenyon 1970, 30), should contain evidence of it.

There are implications of dating Joshua’s destruction of Jericho correctly. The conquest of all of Canaan followed in the next few years, and the evidences of this should correspond in the archaeological record. The Jericho event does not stand alone.

This paper references both biblical and standard (secular) dates, with the underlying assumption that these dates did not coincide in ancient times.

About Jericho

Jericho, named after the Canaanite moon god, Yerach (Noll 2013, 337), is one of the oldest cities in the world, first settled in about 9000 B.C. secular (Kenyon 1970, 316). Today the ancient tell (mound) is about 4 ha (10 acres) in size, and 21 m (70 ft) high (Kenyon 1970, 39). Small as it was, its location was important because it had a reliable year-round spring that put out 4,000 to 5,000 liters (over 1,000 gallons) of water per minute (Nigro 2014, 3). In a desert climate, that amount of water was a significant attraction for anyone wishing to settle (Kenyon 1970, 29, 41). Jericho is the lowest town in the world, at 274 m (900 ft) below sea level, situated in the great rift of the Jordan Valley (Kenyon 1957, 23).

Many excavations at Jericho over the years since 1867 (Kenyon 1957, 19, 31–33; Nigro 2016) have left the mound with the appearance of a giant sandbox that has been totally dug up (see fig. 2). We might wonder how archaeologists today are able to determine anything from what appears to be nothing but an amorphous heap of ruin. Depending on what is considered a separate city wall, there are as many as 17 walls on top of each other during the Bronze Age, the archaeological period approximately 3300–1500 B.C. secular (Kenyon 1957, 182). The sheer number of Jericho’s walls complicates determining which wall was destroyed by the Children of Israel.

Fig. 2. View of the ancient Tell es-Sultan/Jericho. Tamar Hayardeni, (יריחו (מידע נוסף בשם הקובץ), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jericho_-_Tel_Es-Sultan1.jpg. GNU Free Documentation License.

Joshua’s Wall

The Early Bronze IIIB wall is supported in this paper as the one that fell miraculously for Joshua. It has everything going for it—except that the 2350 B.C. secular date of its destruction is nearly a thousand years earlier than the generally accepted 1400 B.C. biblical date for this event. This dating difference will be dealt with later on when we show that there is a major divergence between the biblical and secular timelines that accounts for this apparent dating anomaly.

The most important characteristic that we are looking for, that distinguishes Joshua’s wall from the others before and after it, is that its destruction had to have marked a sharp discontinuity in the culture of Jericho’s inhabitants. Before the conquest, the inhabitants of Jericho were pagan Canaanites. After Joshua’s forces burned the city and killed all its inhabitants, members of the Tribe of Benjamin would have begun to inhabit it (Benjamin was allotted territory that included Jericho [Joshua 18:11, 12]). The importance of this change in culture cannot be overestimated, as it is significant in determining which wall fell for Joshua.

Archaeologists such as Kenyon (1957, 186–188, 192) and Garstang (1948, 91) state clearly that there was a distinct difference in culture between the people who lived in Jericho before and after the destruction of this EB IIIB wall. Kenyon calls the newcomers “nomadic invaders” who must have dwelled in tents. The style of pottery changed markedly (Kenyon 1957, 189) and these invaders were clearly concerned with spiritual things (Kenyon 1957, 194). All this points to these incomers as the Children of Israel, although Kenyon did not realize it.

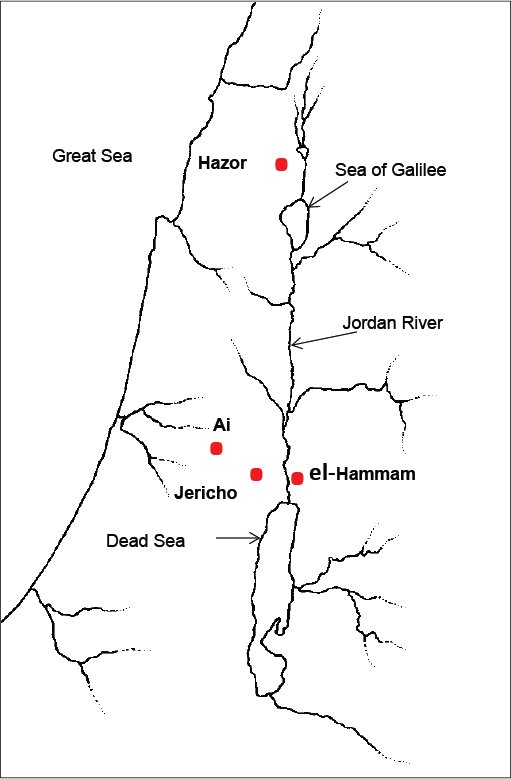

This wall around the crown of the mound had casemate construction (Chandler 2009). It was composed of parallel inner and outer walls that were cross linked to each other by short walls at right angles, giving the wall great strength. The entire wall construction was as much as 11 m (36 ft) wide (Gallo 2013). The rooms between the walls were used for storage or living space, or filled with debris. There were square towers as well as bastions (projections) spaced along the wall (see fig. 3). Archaeologists do not tell us what the original height of this double wall was; this is not surprising because the Bible says that this wall fell flat (Joshua 6:20), except for the place where Rahab’s house was located. Whether any of that piece of wall survived later wall constructions is doubtful.2

Fig. 3. Drawing of one style of bastion, although designs can vary. A bastion is a projection that extends outward from a curtain wall (defined as the wall connecting two towers) of a fortification. Pearson Scott Foresman “ Line art drawing of a bastion,” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bastion_(PSF).jpg. Public Domain.

This EB IIIB city was fiercely burned. It is the level of Jericho that various archaeologists (whether believers or not) had picked as most likely to fit the biblical story because of the extraordinary fire of its destruction. As Nigro says (2019, 103):

At the end of the urban period the flourishing city of Sultan IIIc2 (EB IIIB) was definitely destroyed by a terrible conflagration, which has been documented all over the site. The double city-walls were completely destroyed, and evidences of heavy burning were recognized along the whole fortification perimeter. Inside the fortifications all the buildings of the EB IIIB city were set on fire, and they were filled up by ashy layers with charcoals, broken and charred bricks and other carbonized material, evidence of the incredibly fierce fire which burned the whole city and its content.

Nigro (2016, 12) also says that this event

was presumably deeply impressed in the collective memory of Levantine peoples, perhaps to the point of being echoed in the Biblical narrative of Joshua.

Kenyon (1957, 189) describes this burning of the city and adds that

The disaster was indeed complete, for this was the end of Early Bronze Age Jericho.3

This dating of the fall of Jericho at the end of the Early Bronze is supported by other scholars: Courville (1971, 87), Down (2006), Osgood (1986; 2015, 41–43), and Porter (2017).

Hiel’s Wall

After the fall of Jericho, Joshua pronounced a curse on anyone who would rebuild its wall (Joshua 6:26). Although Jericho’s walls had been rebuilt repeatedly during the previous 700 years of the Early Bronze period, the wall was not rebuilt this time for hundreds of years. Presumably curses of this sort were taken seriously (Kitz 2007).

It was about 500 years after Joshua’s curse (Jones 2005, 279)4 that a wall was built by Hiel the Bethelite during the reign of Ahab (1 Kings 16:34; 16:29). We are not told why Hiel built this Jericho fortification. We do know that under Ahab, who had married the pagan Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal king of Sidon, the people of the land had wandered far from worship of God (1 Kings 16:31–33; 1 Kings 21:22). Because of the Baal worship of those times, it might not be surprising that Hiel would disregard Joshua’s long-ago curse. Whatever, Hiel showed defiance in building this wall, and as a result he paid the steep price of losing his oldest and youngest sons in construction of the foundation and gates, as Joshua had predicted (1 Kings 16:34).

We would therefore expect archaeologists to find a wall that dates at least 500 years after the conquest on the standard secular timeline.

There is such a wall. Nigro tells us that there are remains of a solid 2 m-wide mudbrick construction with buttresses and rectangular towers, built at the bottom of the tell, dated toward the end of the Middle Bronze I period (1950–1800 B.C. secular) (Nigro 2006, 25, 26, 28). Kenyon also mentions this mudbrick wall from the early Middle Bronze (1957, 214). This solid wall was completely different in design than Joshua’s casemate-construction double wall above. See fig. 4 for examples of buttresses.

Fig. 4. St. Laurence’s Church, Bradford-on-Avon, England, has two simple buttresses on each side of the entrance to support the wall. The mudbrick fortification wall of Jericho built by Hiel three thousand years ago would have had simple buttresses, perhaps similar to these. Buttresses of various styles have been used throughout history. Charles Miller, “Saxon church, Bradford on Avon,” https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Saxon_church,_Bradford_on_Avon.jpg. CC BY 2.0.

The difference of approximately 500 years between the destruction of the EB IIIB wall and the building of this MB I mudbrick wall supports the latter as Hiel’s wall. According to archaeologists, there are no other walls between the EB IIIB wall (see previous section) and the MB II─III wall (see next section), making this essentially the only candidate for Hiel’s wall.

During those 500 years, there was no occupation of the tell (mound) at first, with a gradual increase in population taking place over time (Nigro 2006, 23). This agrees with the biblical narrative, in which all the inhabitants of Jericho were killed by Joshua’s troops in the conquest. Mention of Jericho is made later in 2 Samuel 10:5 when David told his servants to stay at Jericho until their beards had grown back.Jericho would have still been an unwalled town at that time. David’s reign began in 1055 B.C., and Ahab died in 897 B.C., a difference of 158 years, which would have been the maximum possible time between this incident and the building of Hiel’s wall (for these biblical dates, see Jones 2005, 279).

We note that the Bible does not say that Hiel built a city, but only a wall. Up to the time of Hiel, although there were clearly buildings in the city of Jericho, perhaps a lot of them, the city had had no wall around it.

Hiel’s wall was superseded by the great embankment fortifications below.

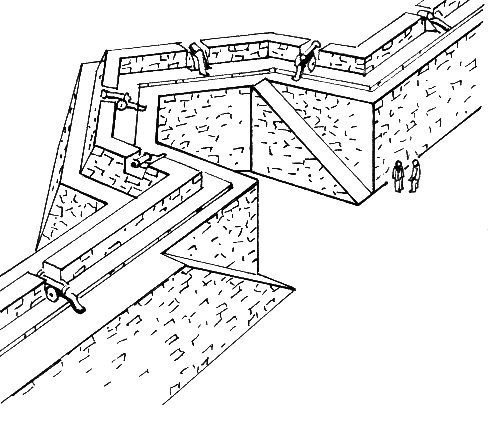

The Middle Bronze II─III Great Embankment Fortifications

Built sometime later than Hiel’s wall above, these MB II─III fortifications are described by archaeologists as having a wall around the crown of the tell and a second wall, made of stone that was topped with brick, around the foot of the tell (Kenyon 1957, 214–220). The ramparts between the two walls consisted of a plastered slanted surface called a glacis. This represented a major change in design of fortifications from the earlier walls (Kenyon 1957, 220) (see fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Cross section of the MB II–III great embankment fortification of Jericho. There would have been no houses visible on the slanted glacis between the upper and lower walls, as these buildings were all filled in by the third and final stage of the embankment (Nigro et al. 2011).

We include these fortifications here because they are claimed to be Joshua’s wall by Bryant Wood of Associates for Biblical Research (Wood 1999). ABR do not recognize divergence of the biblical and secular timelines, and therefore for Wood these fortifications come closest to the biblical date of about 1400 B.C. for Jericho’s destruction. Kenyon, however, dates the destruction of these walls at about 1550 B.C. secular (Kenyon 1978, 38), about 250 years after Hiel’s wall was built. Kennedy (2023) also indicates these fortifications as those of Joshua.

It is most likely that these fortifications were destroyed by earthquake, as Jericho is in an earthquake zone (Wetzler et al. 2015).

There is considerable special pleading inherent in the claims that this must be Joshua’s wall. For one thing, there was no change of culture before and after its destruction, as would be the case if the Canaanite inhabitants were replaced by Israelites; the same culture prevailed from about 1900 to 1200 B.C. secular (Kenyon 1957, 228). For another, it is not “a wall” as the Bible says; it is a pair of walls situated at the head and foot of the tell. Also, mudbricks were typically very large (Ripepi 2019, 215–229) and it would have been difficult for Joshua’s forces to climb up over the pile of broken pieces to scale the stone revetment. There would then have been the very steep (probably plastered) slippery rampart to climb to reach the top (Kenyon 1957, 218).

The destruction of these fortifications does not correlate with the biblical story. On examination of the nearby tombs that date to this event, Kenyon concludes it is likely that the inhabitants first suffered some kind of plague, after which the city was destroyed by fire. After the fire, this level of Jericho was abandoned for nearly two hundred years (Kenyon 1957, 255).

Garstang points out that Jericho is not mentioned in the Amarna letters (correspondence between Egyptian and Canaanite representatives), unlike many other cities in the south of Israel/Judah (Garstang 1948, 126). He takes this to mean that Jericho must have been in ruins during the approximate 30-year period of these letters, and was not a walled city with a king. He is correct on this because according to the secular timeline, the Amarna letters date a couple of hundred years after the destruction of the great fortification system (Moran 1992, xiii).

Dating the Conquest

In dating Jericho’s destruction by Joshua at 2350 B.C. secular (the end of EB III), we are also dating the conquest of the entire Promised Land. This campaign took place within the following few years of Jericho’s destruction (Jones 2005, 278). Jones calculates about six years between crossing the Jordan into Canaan and ending the war. Archaeology should support this scenario, and we see that it does.

After Jericho, the next city in Joshua’s sights was Ai (Joshua 7, 8), which was most likely the ruin called et-Tell today.5 This site is situated a short distance west of Jericho, and fits the biblical geographical indications of Genesis 12:8 and 13:3. Built on a rocky outcrop, it is 11 ha (27.5 acres) in size. The EB IIIB destruction of Jericho backs et-Tell as Ai, because et-Tell was violently destroyed at the same time (Kenyon 1970, 115; Livingstone 1967).

As the conquest continued, Hazor (also spelled Hatzor) was a major city north of the Sea of Galilee that Joshua burned on its mound (Joshua 11:13 NIV). The ruins of Hazor consist of a high mound (tell) about 12 ha (30 acres) in area at one end of a much larger low mound; the entire city eventually covered over 81 ha (200 acres). Most archaeologists have concentrated on the destruction in the thirteenth century B.C. (secular) of the larger area of the lower mound. However, it would have been the smaller high mound of Hazor that Joshua destroyed (Joshua 11:10–13), because this is where the Early Bronze remains are located. The lower part did not yet exist in Joshua’s time (Anonymous 1999). More recent work on the high mound has shown that Hazor suffered a demise at the end of the EB III (Lev, Bechar, and Boaretto 2021). The rest of the cities of Canaan were to be conquered (but not burned), and their inhabitants killed (Joshua 11:12).

Archaeologists also describe the destruction of the cities in the area east of the Jordan River as taking place at this time. Richard states that there was a post-EB III collapse east of the Jordan River, “destruction and/or abandonment of every walled site” (2014, 343). This would correlate with the campaign of the Children of Israel through the territory of Sihon king of Heshbon (Numbers 21:21–30) and Og king of Bashan (Numbers 21:33–35) before crossing the Jordan into Canaan. The large mound of el-Hammam, located directly across the Jordan River from Jericho, was also destroyed at about 2350 B.C. secular.6

After the inhabitants of the Canaanite cities were destroyed, occupation by the Israelites would have been sparse compared to that of the previous population. We would expect this because God had said that the Children of Israel were fewer than any of the seven Canaanite peoples in the land (Deuteronomy 7:1). Also 2½ tribes stayed on the eastern side of the Jordan, reducing even further the number that settled in Canaan on the west side (Numbers 32). Archaeology supports this conclusion. According to the University of Pennsylvania Museum (1999), “by 2300 BCE (secular), most of the towns in the southern Levant had been abandoned or reduced in size.”

Synchronization of the Biblical and Secular (Conventional) Dates of the Conquest

The question is how a biblical conquest date of about 1400 B.C. can be synchronized with the end of the Early Bronze IIIB, dated to about 2350 B.C. secular (there is variation on this latter date among scholars).7

Although many readers may be familiar with the dynasties of Egypt, this paper is based on the Bronze Age classification of dating because that is what archaeologists use for discussing dates of ancient Canaan. In table 1 we show how the biblical and Bronze Age dates are interconnected.8

| Bronze Age Period | Standard Date | Biblical Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joshua’s Wall destroyed | End Early Bronze IIIB | 2350 B.C. | 1410 B.C. (Conquest) |

| Hiel’s Wall built | End Middle Bronze I | 1800 B.C. | 900 B.C. |

| Great Embankment destroyed | Middle Bronze II–III | 1550 B.C. | 700 B.C. (est.) |

The importance of timeline synchronization is underscored by scholars who regularly declare that the Bible is wrong on matters such as the date of the fall of Jericho, because the secular dates of archaeologists don’t coincide with the biblical timeline. An example of this is Kenyon, daughter of a biblical scholar, who assures us that “chronology based on the Biblical record cannot be taken literally” (Kenyon 1957, 258–259). Others deny that the Jericho conquest actually happened at all. Friedman, for instance, calls the fall of Jericho an earthquake myth (Friedman 2020). The attitude of these people is that their archaeology overrides what the Bible says. Satan attacks the veracity of the Bible through timeline confusion, and He does it well. Chronology matters therefore constitute an important branch of biblical apologetics.

Conclusions

Because there was a distinct change in culture of the inhabitants of Jericho after the destruction of the EB IIIB wall, we conclude that this was the one that fell miraculously before Joshua’s forces. This dates that event to about 2350 B.C. secular, at the end of the Early Bronze period. The EB IIIB time of Joshua’s destruction is when Ai, Hazor, and cities east of the Jordan River were also destroyed, backing up this date for the destruction of Jericho and the beginning of the conquest of Canaan. Hiel’s wall was the solid mudbrick MB I wall dated to about 1800 B.C. secular. The MB II–III fortifications (destroyed in 1550 B.C. secular), widely claimed to be Joshua’s, were actually built later than Hiel’s wall. Based on the Bronze Age dating system used by archaeologists, the divergence of the biblical and secular timelines is nearly a thousand years at the time of Jericho’s destruction.

References

Anonymous. 1999. “Hatzor─The Head of All Those Kingdoms.” Israeli Missions Around the World. https://embassies.gov.il/MFA/IsraelExperience/history/Pages/Hatzor%20-%20The%20Head%20of%20all%20those%20Kingdoms.aspx.

Chandler, Luke. 2009. “Ancient Casemate Walls—An Inexpensive, Flexible Defense.” https://lukechandler.wordpress.com/2009/08/19/ancient-casemate-walls-an-inexpensive-flexible-defense/.

Collins, S. and L. Scott. 2013. Discovering the City of Sodom: The Fascinating, True Account of the Discovery of the Old Testament’s Most Infamous City. New York, New York: Howard Books.

Courville, Donovan A. 1971. The Exodus Problem and its Ramifications. Vol. 1. Loma Linda, California: Crest Challenge Books.

Down, David. 2006. “The Story of Jericho.” Journal of Creation 20, no. 1 (March): 86–92.

Friedmann, J. L. 2020. “The Fall of Jericho as Earthquake Myth.” Jewish Bible Quarterly 48, no. 3 (July–September): 171–178.

Gallo, Elisabetta. 2013. “The EB III Fortifications of Tell Es-Sultan Jericho in Area B and B-West.” Scienze dell’ Antichità 19: 2–3.

Garstang, J. and J. B. E. Garstang. 1948. The Story of Jericho. 2nd ed. London, England: Marshall, Morgan and Scott, Ltd.

Habermehl, A. 2013. “Revising the Egyptian Chronology: Joseph as Imhotep, and Amenemhat IV as Pharaoh of the Exodus.” In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Creationism. Edited by Mark Horstemeyer. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship.

Habermehl, Anne. 2017. “Sodom—Part 1.” Journal of Creation 32, no. 2 (August): 53–60.

Jones, Floyd Nolen. 2005. The Chronology of the Old Testament, 16th ed. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Kennedy, Titus. 2023. “The Bronze Age Destruction of Jericho, Archaeology, and the Book of Joshua.” Religions 14, no. 6 (June): 796–814.

Kenyon, Kathleen. 1957. Digging up Jericho. London, England: Ernest Benn Limited.

Kenyon, Kathleen. 1970. Archaeology in the Holy Land. 3rd ed. New York, New York: Praeger Publishers.

Kenyon, Kathleen M. 1978. The Bible and Recent Archaeology. Atlanta, Georgia: John Knox Press.

Kitz, Anne Marie. 2007. “Curses and Cursing in the Ancient Near East.” Religion Compass 1, no. 6 (October): 615–627.

Lev, Ron, Shlomit Bechar, and Elisabetta Boaretto. 2021. “Hazor EB III City Abandonment and IBA People Return: Radiocarbon Chronology and its Implications.” Radiocarbon 63, no. 5 (October): 1453–1469.

List of archaeological periods (Levant). 2023. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_archaeological_periods_(Levant).

Livingstone, G. Herbert. 1967. “Special Report: The Excavation of et-Tell (Ai) in 1966.” The Asbury Seminarian 21, no. 2 (April) :31–37.

Moran, William L. ed. and trans. 1992. The Amarna Letters. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Nigro, Lorenzo. 2006. “Results of the Italian-Palestinian Expedition to Tell es-Sultan: At the Dawn of Urbanization in Palestine.” In Tell-es-Sultan─Jericho: Site Management, Conservation, and Sustainable Development , Proceedings of the International Workshop Held in Ariha 7–11 February 2005. Edited by L. Nigro, and H. Taha, 1–40. Rome, Italy: “La Sapienza” Expedition to Palestine and Jordan.

Nigro, Lorenzo. 2014. “Aside the Spring: Tell Es-Sultan/Ancient Jericho: The Tale of an Early City and Water Control in Ancient Palestine.” In A History of Water: Series III, Volume 1: Water and Urbanization. Edited by T. Tvedt and T. Oestigaard, 25–51. London, United Kingdom: I. B. Tauris.

Nigro, Lorenzo. 2016. “Tell es-Sultan 2015: A Pilot Project for Archaeology in Palestine.” Near Eastern Archaeology 79, no. 1 (March): 4–17.

Nigro, Lorenzo. 2019. “Tell es-Sultan/Ancient Jericho in the Early Bronze Age II─III.” In Rome La Sapienza Studies on the Archaeology of Palestine and Transjordan. Vol. 13. Edited by L. Nigro, 79–108. Rome, Italy: Sapienza University of Rome. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342171034_Tell_es-Sultanancient_Jericho_in_the_Early_Bronze_Age_II-III.

Nigro, Lorenzo, Maura Sala, Hamdan Taha, and Yassine Jamoussi. 2011. “The Early Bronze Age Palace and Fortifications at Tell es-Sultan/Jericho.” The 6-th—7th Seasons (2010–2011). Rome, Italy: “La Sapienza” University and the Palestinian MOTA-DACH.

Noll, K. L. 2013. Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: A Textbook on History and Religion. London, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury.

Osgood, A. J. M. 1986. “The Times of the Judges—The Archaeology: (a) Exodus to Conquest.” Ex Nihilo Technical Journal 2, no. 1 (April): 56–76.

Osgood, John. 2015. Egypt, Israel and the Exodus: The Evidence is Real. Queensland, Australia: Self-published.

Porter, Robert M. 2017. “Towards an Alternative Reconciliation of the Old Testament with History and Archaeology: Exodus at End of Old Kingdom and Conquest at End of Early Bronze III, Part 1.” Chronology and Catastrophism Review 1: 49–53. https://www.academia.edu/45351887/Towards_an_Alternative_Reconciliation_of_the_Old_Testament_with_History_and_Archaeology_Exodus_at_end_of_Old_Kingdom_and_Conquest_at_end_of_Early_Bronze_III.

Regev, Johanna, Pierre de Miroschedji, Raphael Greenberg, Eliot Braun, Zvi Greenhut, and Elisabetta Boaretto. 2012. “Chronology of the Early Bronze Age in the Southern Levant: New Analysis for a High Chronology.” Radiocarbon 54, nos. 3–4: 505–524.

Richard, Suzanne. 2014. “The Southern Levant (Transjordan) During the Early Bronze Age.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant: c. 8000–332 BCE. Edited by Ann E. Killebrew, and Margreet Steiner, 330–352. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Ripepi, G. 2019. “Mudbricks and modular architecture at Tell es-Sultan from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age.” In Digging Up Jericho: Past, Present and Future. Edited by Rachael Thyrza Sparks, Bill Finlayson, Bart Wagemakers, and Josef Mario Briffa, 215–229. Oxford, England: Archaeopress. http://www.lasapienzatojericho.it/Biblioteca/Jericho/Ripepi_2020_DiggingUpJericho.pdf.

University of Pennsylvania Museum. 1999. “The First Towns: Early Bronze Age 3300–1950 BCE.” The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. https://www.penn.museum/sites/canaan/EarlyBronzeAge.html.

Wetzler, Nadav, Amir Sagy, Yael Sagy, Yoav Nahmias, and Vladimir Lyakhovsky. 2015. “Active Transform Fault Zone at the Fringe of the Dead Sea Basin.” Tectonics 34, no. 7 (July): 1475–1493.

Wood, Bryant. 1999. “The Walls of Jericho.” Creation Ex Nihilo 21, no. 2 (March): 36–40.

Wood, Bryant G. 2012. “Excavations at Kh. el-Maqatir 1995–2000, 2009–2011: A Border Fortress in the Highlands of Canaan and a Proposed New Location for the Ai of Joshua 7–8.” https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/sites/bibleinterp.arizona.edu/files/docs/excav25.pdf.