The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

Osgood recently published a critique of Habermehl’s (2011) paper proposing the location of Babel was in the Khabur Triangle of Upper Mesopotamia. The authors point out weak arguments by both Osgood and Habermehl and suggest that the Prepottery Neolithic culture would be a more probable site for Babel.

Keywords: Shinar, Tower of Babel, Prepottery Neolithic

Osgood’s recent critique (2024) of Habermehl’s paper on the location of Babel (2011) judges Habermehl rather harshly but falls short of being a strong critique of her position, despite the need for one. We begin from a position quite close to Osgood’s, supporting a chronology based on the Masoretic Text, yet we find that his arguments against Habermehl’s Upper Mesopotamian Babel are largely lacking in substance. We also argue for a geographical position closer to Habermehl’s, that the site of Babel was in the region of ancient Subartu on the upper Tigris River Valley (Griffith and White 2021).

The Ancient Persian Gulf Shoreline

Habermehl sets chronological limits on the duration from the Flood to the founding of Babel and Egypt based on erroneous geological arguments. This was a bad argument on her part that needs refutation. While Osgood dismisses Habermehl’s claimed Persian Gulf shoreline between Hit and Samarra in Iraq, he offers no evidence that her very specific claim was mistaken. Such evidence is readily at hand, however (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The southern rim of the Tharthar Depression in Red. Google Earth modified by author. Fair Use.

The “ancient shoreline” she found described on old maps North of Babylon is the rim of the Tharthar Depression, just South of Lake Tharthar (33°40’56.26”N, 43°11’58.81”E). This “shoreline” faces North, not South, and it was formed by the dissolution of gypsum bedrock by rainwater over centuries. The raised southern rim is easily visible in satellite images and matches the “shoreline” shown on her old map. Sissakian (2011) found that the depression is not shown on maps from the 1600s, and concluded that it formed since the Holocene, possibly as recently as the seventeenth century of the current era. Thus, it was never an ocean shoreline at all and is irrelevant to the chronology and possible locations of Babel.

Despite making an erroneous geological argument against a Lower Mesopotamian Babel based on a nonexistent ancient shoreline, Habermehl’s other arguments are considerably stronger.

Shinar = Senaar = Sumer?

After citing other theories, Habermehl offered an original etymology for the name “Shinar” which seems quite reasonable:

This author considers that what makes the most sense would appear to be the suggestion that “Shinar” is simply a Semitic language form of “two rivers” (in Hebrew, “shene nahar”) (for example, Rollin 1836, p. 284; Smith 1948, p. 622). Shinar, then, would be “land of two rivers,” a name closely related in meaning to the Greek, “Mesopotamia.” (Habermehl 2011, 26)

Strongly disagreeing, Osgood offers his own original etymology for Shinar as being superior:

Shinar was given to us by Moses, the Egyptian-trained author/editor of the Torah. It comes not from Aramaic but from the Hebrew transliteration of the Egyptian word for Sumer = Senaar (in English). (Osgood 2024, 215)

Osgood claims that Shinar was a cognate of the original name, Sumer. That supposition was popularized by Assyriologists in the nineteenth century (Sayce 1895, 67–68), though without any real evidence other than the similarity of the first and last consonants. Osgood adds the original claim that Moses transliterated the Egyptian word “Senaar” into Hebrew and that the Egyptian word Senaar meant Sumer, concluding that Shinar had to have been in Sumeria (2024, 215–216).

Yet, in his very confident assertion, Osgood provides nary a whit of evidence for either side of his two-step etymological transformation. A reference to any Egyptian inscription indicating that “Senaar” was understood to be in Asia rather than a province on the Blue Nile would have been precisely the sort of evidence that would support his argument.

Potts cites Zadok as claiming that Shinar was derived from an Amorite word quite similar to Habermehl’s proposal:

It has recently been shown, however, that Shinar is derived not from Sumer but from Shanhara, the name given to Babylonia during the Kassite period (c. 1400–1155 BC) by the population living west of the Euphrates (Zadok 1984:244). (Potts 1997, 43)

Given that the Amorite population living to the West of Euphrates in the Kassite period spoke a Semitic language, Habermehl’s Hebrew etymology for Shinar appears to be better supported than Osgood’s. Yet, if we are brutally honest, scholars must admit that we don’t have a series of inscriptions over many centuries showing the transformation of the word Shinar from a source in either Sumerian or Semitic languages. Going back to the Hellenistic Era, scholars have a very long history of inventing etymologies without evidence, and that is why etymology should be given the lowest weight compared to other kinds of evidence.

The Wiseman hypothesis, which holds that Genesis 10:1–11:9 was originally written by Shem (Taylor 1994), casts Osgood’s claimed Egyptian source for the word Shinar further into doubt. If Shem was the author of the Genesis 10 tablet, there is no reason to believe that his knowledge of the word Shinar was first transmitted from Lower Mesopotamia to Egypt via the invasion by the Pathrusim by sea before finally being translated into Hebrew by Moses. If Shem was the author of Genesis 10, it would be more likely that he simply handed down the tablets or scrolls to Abraham who passed them down to Jacob, who brought them to Egypt, whence they later came into the possession of Moses.

There are several sites with names similar to Shinar found between Çinar, Turkiye on the Upper Tigris River, the Sinjar Mountains in the Khabur Triangle of Syria and Iraq, and Daniel’s reference to Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon as being in Shinar (Daniel 1:2). Rather than insisting that only one of these localities was the real Shinar and inventing a supportive etymology, it might be more realistic to recognize that Shinar had a meaning similar to Mesopotamia, which included the entire region between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers from the Taurus Mountains to the Persian Gulf. Therefore, we might find relics of the name Shinar anywhere in that watershed. Just because a locality bore a name similar to the Hebrew “Shinar” doesn’t necessarily mean that the locality was the original site of Babel; and the original site of Babel may have later lost the name, Shinar. A broad case considering all of the available evidence should be made.

Osgood follows Rohl’s identification of Eridu as the site of Babel (Osgood 2015, 48) and Woolley’s identification of Ur III as Abraham’s Ur of the Chaldees (2024, 216). Both sites are located southwest of the Euphrates River, and therefore neither site is between the rivers, nor on the opposite side of the Euphrates from Canaan (Joshua 24:14).

Disregarding Archaeological Evidence

Both Habermehl’s paper and Osgood’s critique ignore the archaeological existence of the Prepottery Neolithic A and B sites located in the upper Tigris and Euphrates watersheds. As the oldest civilization yet found that constructed buildings, the Prepottery Neolithic is the most obvious place to look for the first four cities built by Nimrod after the Flood (Genesis 10:8–12). Osgood assumes that Warka was Nimrod’s Erech, despite the occurrence of at least one other ancient city that was a cognate of Erech, namely Khurkh, or Kiriki, on the upper Tigris River (Griffith and White 2021). Likewise, Osgood declares Woolley’s Lower Mesopotamian Ur to have been Abraham’s Ur of the Chaldees, without considering more recent scholarship such as that of Cyrus Gordon who found that Ur Kassidim was referenced in the Ebla tablets as being near Haran. Gordon identified it as the ancient city of Urfa, which happens to be only ten miles from the more recently discovered site of Gobekli Tepe (Gordon 1977).

By accepting the short Masoretic Text chronology of Genesis, placing Babel in Lower Mesopotamia, and identifying the Dispersion with the Uruk Culture (Osgood 2015, 48–49) Osgood creates a chronological problem for himself. The Genesis narrative places the dispersion at either the birth of Peleg (Genesis 10:25) or two generations later after Joktan’s 13 sons had reached maturity (Genesis 10:26–30). Thus the MT chronology places the Dispersion only 101 to 180 years after the Flood. Archaeologically, Osgood must compress the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Prepottery Neolithic, Hassunah, Samarra, Halaf, Ubaid, and Uruk cultures into no more than 180 years between the Flood and the Dispersion. Habermehl’s hypothesis places Babel in the Halaf culture which was two steps closer in time to the Flood than Osgood’s Uruk period Babel.

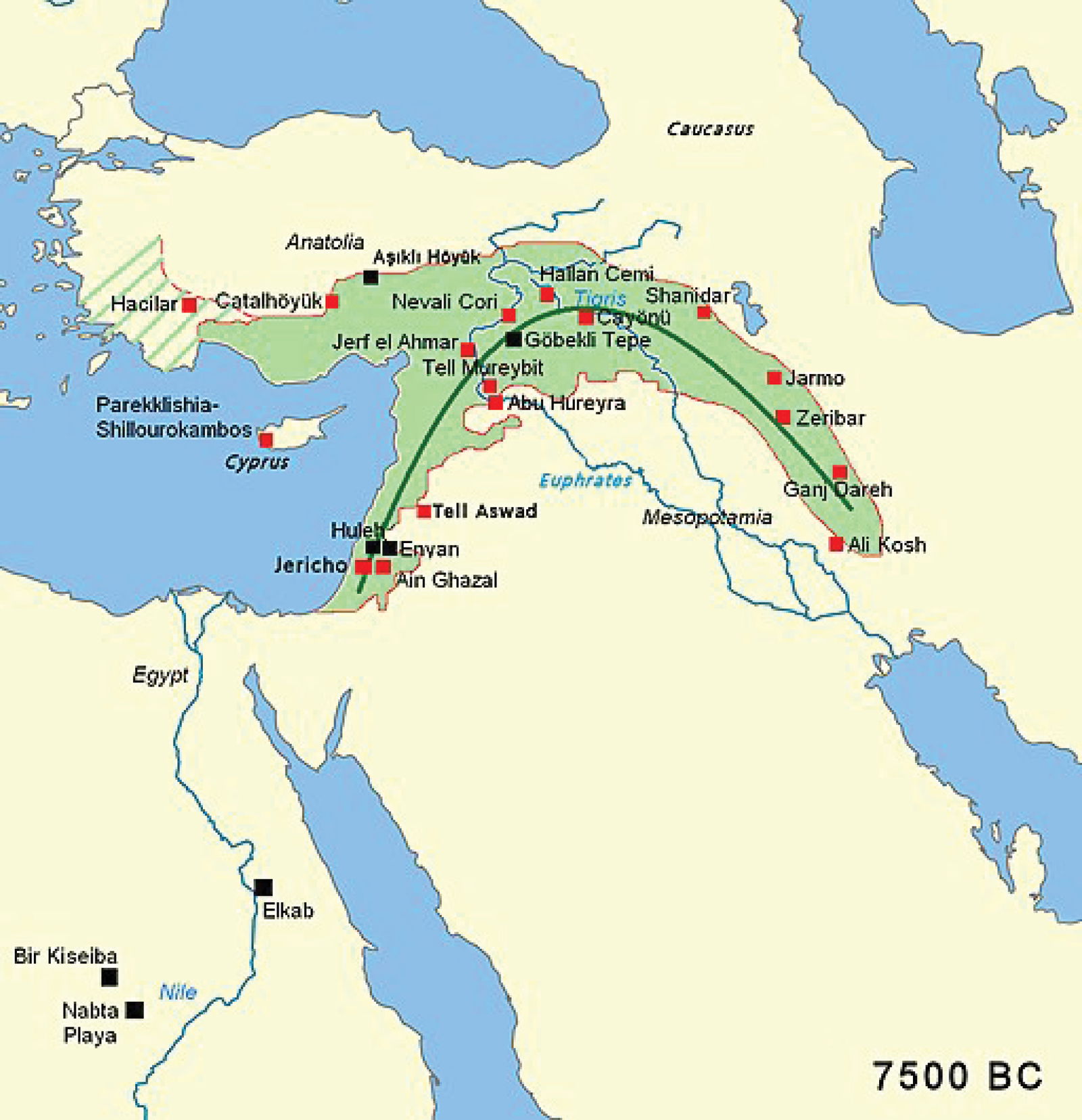

We have argued that the Paleolithic and Mesolithic cultures were hunting and exploration campsites that were contemporary with the Prepottery Neolithic. Recognizing the Prepottery Neolithic as the culture of Babel in Upper Mesopotamia would relieve the need to chronologically compress multiple sequential cultures into such a short period. However, the Prepottery Neolithic culture has no known sites in Lower Mesopotamia (fig. 2). This argues against Osgood’s Lower Mesopotamian Babel position.

Fig. 2. Map of the distribution of Prepottery Neolithic sites. Bjoertvedt, “Fertile crescent Neolithic B circa 7500 BC; black squares indicate pre-agricultural sites,” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fertile_crescent_Neolithic_B_circa_7500_BC.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Conclusion

Osgood concludes:

In short, despite her bold assertions, Habermehl (2011) has not established the case, and has certainly not “proved” that Shinar lies other than in southern Iraq. (Osgood 2024, 216)

While Osgood’s assertion that Babel was located in Lower Mesopotamia may someday be proven correct, he also has failed to prove his case. At least it can be said that Habermehl cites evidence for her claims.

References

Gordon, Cyrus H. 1977. “Where is Abraham’s Ur?” Biblical Archaeology Review 3, no. 2 (June): 10–14.

Griffith, Kenneth, and Darrell K. White. 2021. “An Upper Mesopotamian Location for Babel.” Journal of Creation 35, no. 2 (August): 69–79.

Habermehl, Anne. 2011. “Where in the World is the Tower of Babel?” Answers Research Journal 4 (March 23): 25–53. https://answersresearchjournal.org/where-is-the-tower-of-babel/.

Osgood, A. John M. 2015. Over the Face of All the Earth. Queensland, Australia: Self published.

Osgood, A. John M. 2024. “Where in the World Is the Tower of Babel? Comments.” Answers Research Journal 17 (March 13): 215–216. https://answersresearchjournal.org/tower-of-babel/where-is-the-tower-of-babel-comments/ .

Potts, Daniel T. 1997. Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations. London, United Kingdom: The Athlone Press.

Sissakian, Varoujan K. 2011. “Genesis and Age Estimation of the Tharthar Depression, Central West Iraq.” Iraqi Bulletin of Geology and Mining 7, no. 3: 47–62.

Sayce, Archibald Henry. 1895. Patriarchal Palestine. London, United Kingdom: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Taylor, Charles V. 1994. “Who Wrote Genesis? Are the Toledoth Colophons?“Creation Ex Nihilo Technical Journal 8, no. 2 (August): 204–211.

Editor’s Note

John Osgood responds:

I am not the least bit interested in answering this reply, which is so full of misunderstandings archaeologically, and interestingly of misreading what I wrote. My personal opinion is that these authors will keep this argument going ad infinitum if given the opportunity, and add confusion to confusion. While they show a significant amount of research in some areas, what comes through is great ignorance of the actual archaeology.

At no stage did I infer that Babel was at Eridu, I don’t know where they got that from. These people have added no further enlightenment on this subject and will leave the average reader in total confusion on the subject. I will leave my answer to Habermehl to stand as is and let the readers decide for themselves. But what is clear is that these authors have no better answer to Sumer and Babel than Habermehl.