The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

This paper evaluates Tremper Longman and John Walton’s claim that the Flood Narrative (FN) in Genesis uses hyperbolic language to portray a historical local flood as a global cataclysm. Though their broader case addresses genre, comparative analysis of ancient Near Eastern literature, and certain scientific issues, this paper focuses specifically on their arguments for hyperbole. After describing their three key arguments, I propose a linguistically informed definition and criteria for identifying and effectively interpreting hyperbole. I then apply that methodological grid built on logical, linguistic, and rhetorical criteria (that is, those involving strategies of persuasion) to test each of their three key arguments. Their first argument—concerning pervasive non-order—meets only four out of ten criteria, none of which pertain to the logical criteria. But even in those criteria that are met, contextual support is still lacking to make a hyperbolic interpretation preferable to a literal interpretation. Their second argument—concerning the Ark’s dimensions—fails to meet any of the proposed criteria. Their third argument—concerning the mechanisms and extent of the Flood—satisfies four criteria but still lacks a contextual basis for an explicitly hyperbolic reading. Given the lack of clear methodology, Longman and Walton’s interpretation is shown to be rather subjective and, perhaps more based on personal impressions than on rigorous and clear criteria. When tested against a consistent grid, their arguments for hyperbole capsize. Therefore, a more objective interpretation points away from hyperbole and toward a global, catastrophic flood.

Keywords: Flood narrative, Noah’s Ark, hyperbole, criteria, methodology, interpretation, Longman and Walton

Introduction

In his fifth book in the “Lost World” series, John Walton partnered with Tremper Longman III to write The Lost World of the Flood (Longman and Walton 2018). They proposed that the Flood Narrative (FN) is a rhetorically shaped interpretation of a historical event that uses hyperbolic language to depict a “natural cataclysm” as an event of “cosmic proportions” in order to convey a theological message of universal significance (Longman and Walton 2018, 37).1 In a more recent work, Longman argues that the hyperbolic interpretation avoids both the exegetical problems of the local flood view and “the challenge of believability” and “the absence of geological evidence” for the global flood view (Longman 2024, 187).

The goal of this paper is to evaluate Longman and Walton’s proposed rereading of the FN as presented in the The Lost World of the Flood. But since their arguments are based on a variety of propositions touching on genre studies, ancient Near Eastern comparative studies, and even geological studies, I will have to delimit my analysis of their proposal to one specific line of argumentation: the use of hyperbole in the FN. I will seek to answer the following question: Do Longman and Walton’s arguments for hyperbole in the FN stand when evaluated through an objective methodological grid for identifying and interpreting hyperbole?

To answer this question, this paper will begin by presenting Longman and Walton’s arguments for hyperbole in the FN. Next, I will present a methodology that employs logical, linguistic, and rhetorical criteria for identifying hyperbole.2 Finally, I will submit Longman and Walton’s arguments to the scrutiny of that objective methodological grid and evaluate their claims.

In the end, this paper will demonstrate that their arguments for hyperbolic interpretation of the FN are deficient and should be rejected.

Arguments for Hyperbole in the Flood Narrative

The first evidence of hyperbole in the FN listed by Longman and Walton is “the description of pervasive nonorder” in Genesis 6:5 (Longman and Walton 2018, 37). In a more recent work, Longman lists this evidence as “the extent of human wickedness” (Longman 2024, 187). For them, those who seek to maintain an overly literal understanding of the expression “every intent of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually”3 cannot satisfactorily explain the descriptions of Noah’s righteousness in Genesis 6:9 after such a universal statement of wickedness (Longman and Walton 2018, 38). So, they take the mitigated interpretation of this supposed hyperbole as simply referring to “an unprecedented level” of nonorder that precipitated God’s actions to restore order (Longman and Walton 2018, 38).

The second evidence of hyperbole in the FN is “the dimensions of the ark” given in Genesis 6:15 (Longman and Walton 2018, 38). They assert that “the dimensions themselves lead us to believe that they are hyperbolic numbers” (Longman and Walton 2018, 38).4 The basis for their conclusion is that they find it “hard to imagine ancient readers taking this description as if it referred to an actual boat,” (emphasis added) since they would have no frame of reference for such a large boat in the ancient world (Longman and Walton 2018, 38). Another difficulty with taking the ark’s dimensions literally (that is, as corresponding to the actual size of the vessel made by Noah) is that “it is hard to imagine Noah and his family accomplishing such a task” (emphasis added) of building an ark of a size comparable to modern ships without the power tools and skilled workers available today (Longman and Walton 2018, 39–40).5 Finally, they argue that in ANE flood accounts boat dimensions are typically “hyperbolic and inherently not seaworthy” (Longman and Walton 2018, 40, 75).6 They further develop this point later by citing Irving Finkel’s study which asserts that despite the shape and dimensions of Noah’s Ark being different from those of the epics of Atrahasis and Gilgamesh, the floor space of them all is only slightly different: 15,000 square cubits (Noah’s Ark) compared to 14,400 square cubits (Atrahasis and Gilgamesh) (Longman and Walton 2018, 61n1).7

Coupled with this argument concerning the size of the Ark, Longman lists “the amount of animals” Noah had to take in and care for as an indication of hyperbole (Longman 2024, 187), but he does not elaborate on this or any other of the six evidences he lists. Walton, in his NIV Application Commentary on Genesis, lists several logistic problems that he and other scholars have with understanding the Flood as an actual global event. Among these problems is that of transporting and caring for “about 42,000 animals” (Walton 2001, 323).8 In arguing against the local flood view, Longman and Walton do mention that the description of the animals that went in the Ark, including the birds, should be seen as one of the indications of the author’s intentional (hyperbolic) use of “universalistic language” to depict the Flood as a worldwide event (Longman and Walton 2018, 46–49).

The third evidence of hyperbole in the FN is the description of the Flood itself. Here Longman and Walton claim that both the mechanisms of the Flood (Genesis 7:11), which, in their view, reflect “an ancient cosmology,” and the height of the Flood waters covering “all the high mountains under all the heavens” (Genesis 7:19–20) would have been understood by the original audience as hyperbole (Longman and Walton 2018, 40–41).9 They argue that the expression “under all the heavens” (תַּחַת כָּל־הַשָּׁמָיִם) is used elsewhere in the Old Testament (OT) (for example; Genesis 41:57; Exodus 9:6; Deuteronomy 2:25) and in Ancient Near Eastern (ANE) literature in a non-absolute, regional (but hyperbolic) sense (Longman and Walton 2018, 69).10 When comparing the Flood narrative with its ANE parallels, Longman and Walton also observe that the description of the extent of the destruction of humanity and animals by the biblical text “is more explicit than the Mesopotamian versions” (Longman and Walton 2018, 70). However, they argue that the repeated use of the Hebrew word translated as “all” (כֹּל) is part of a “universalistic rhetoric” that is “in keeping with the use of hyperbole” (Longman and Walton 2018, 69–70).

For Longman and Walton, all of these evidences indicate that the author of the FN interprets the historical event he is describing as having a universal “impact and significance” (Longman and Walton 2018, 45). But that does not mean the historical event behind the FN had a universal geographical scope (Longman and Walton 2018, 45, 49). Thus, Longman maintains that the text indicates “the author felt that everything was covered . . . even the tallest mountains of the region,” so for us to appreciate the author’s intention with his literary description of the Flood “we should imagine a universal destruction” (Longman 2005, 117–118, emphasis added).

Toward a Methodology for Identifying and Interpreting Hyperbole

From the presentation above, it is possible to see that Longman and Walton present little in terms of methodological criteria to lend objectivity to their arguments. Repeated phrases like “it is hard to imagine” indicate that their conclusions are more the result of personal impressions and subjective feeling than of objective criteria. So, in order to evaluate Longman and Walton’s arguments it is necessary at first to arrive at a definition of hyperbole and to establish methodological criteria that can lend greater objectivity to one’s assertions.

Definition

Hyperbole is ubiquitous in human communication both synchronically (that is, in current usage) and diachronically (that is, across the history of literature). According to Robert Evans, hyperbole is “common to all literatures” (Evans 2014, 90; McFadden 2012, 648).11 Its use is also seemingly unrestricted by the age, time, place, culture, or level of education of its users. Yet, it remains an under-researched topic in comparison to other figures of speech (Cano Mora 2009, 25).

Claudia Claridge, in her work Hyperbole in English, sought to fill a gap in the research of this figure of speech (Claridge 2011). She starts her discussion of hyperbole by quoting Quintilian’s observation of hyperbole’s universal and instinctive presence in human communication: “[Hyperbole] is in ordinary use, too, among the uneducated and with country people, no doubt because everybody has a natural desire to exaggerate or to minimize things, and no one is satisfied with the truth. It is pardoned, however, because we do not vouch for what we say” (Claridge 2011, 5).12 But while it may be easy and intuitive to use hyperbole, defining it can be challenging.

Claridge takes up the task of definition and preliminarily defines hyperbole as an expression that “exceeds the (credible) limits of fact in the given context” (Claridge 2011, 5). She then seeks to expand that definition by considering several examples and characteristics of hyperbole and concludes that hyperbole is a figure of speech that “exceeds the limits of fact and appropriateness of expression in the given situation in light of common world knowledge and expectations about the ‘normal’ state of affairs as by seen by an ‘objective observer’ and H[earer]” (Claridge 2011, 5).

More recently, Christian Burgers and a team of scholars working on a project called Hyperbole Identification Procedure (HIP) defined hyperbole as “an expression that is more extreme than justified given its ontological referent” (Burgers et al. 2016, 166). Though shorter, this definition shares with Claridge’s both the presence of scalar features (or gradability along an axis),13 and the idea of an ontological or extra-textual referent against which the excessive statement is judged, enabling the hearer to identify and understand the hyperbole.

McCarthy and Carter add yet another element that contributes to a more complete understanding of hyperbole: the interactive nature of hyperbole that makes it non-deceptive. They argue that “listener reaction is crucial to its interpretation, and the success of hyperbole depends on the listener entering a pact of acceptance of extreme formulations, the creation of impossible worlds, and/or apparent counterfactuality” (McCarthy and Carter 2004, 149, emphasis added).Claridge concurs, when she adds that, in terms of its function, hyperbole is “not intended to deceive,” but to communicate “emotion/intensity” (Claridge 2011, 38).14 Also in alignment with McCarthy and Carter, Gaëlle Ferré affirms that, when confronted with an exaggerated version of reality, “listeners then have a choice of rejecting the shift in footing introduced by hyperbolic speech (by verbal challenge or simple return to the previous frame), or align with speakers with laughter and/or personal contribution” (Ferré 2014, 49–50). Thus, a felicitous interaction between interlocutors in a hyperbolic communication scenario involves ‘‘a kind of joint pretense in which speakers and addressees create a new layer of joint activity” (McCarthy and Carter 2004, 152, emphasis added).

In the area of biblical studies, one of the most significant recent contributions in terms of definition and application to biblical texts was Charles Cruise’s PhD dissertation (Cruise 2017).15 He sought to establish the “ground rules” for understanding and interpreting hyperbole based on a broad linguistic framework in order to “avoid accusations of bias and subjectivity” (Cruise 2017, 107).

Cruise starts with a simple definition of hyperbole: “Hyperbole is a deliberate exaggeration for the sake of effect” (Cruise 2017, 109).16 But he expands his definition by providing six defining characteristics of hyperbole: (1) nonveridicability (that is, the statement is not factually true), (2) intentionality (that is, not accidental, but purposeful), (3) subjectivity (that is, conveying the speaker’s attitude or emotion towards the subject-matter),17 (4) gradability (that is, it exaggerates along a scale that needs to be mitigated to arrive at the correct interpretation), (5) modulation (that is, it can use intensifiers or downtoners), and (6) discrepancy (that is, the speaker’s expectation or wish does not match his/her actual experience) (Cruise 2017, 111–16).

Another important work dealing with hyperbole in biblical studies is Wilfred Watson’s Classical Hebrew Poetry. Watson treats hyperbole as a synonym for exaggeration (Watson 1986, 316). His distinctive contribution is his contention that “the main function of hyperbole, in fact, is to replace over-worked adjectives (such as ‘marvellous,’ ‘enormous,’ ‘colossal’) with a word or phrase which conveys the same meaning more effectively” (Watson 1986, 319, emphasis original). In performing this function hyperbole displays the “economy of expression, which is the hallmark of good poetry” (Watson 1986, 317).

What can be gleaned from the preceding discussion is that the intuitive simplicity of hyperbole’s pragmatic usage masquerades the complex web of semantic factors involved in it. As a result, a definition of hyperbole can be either simple and incomplete or aim for completeness but be cumbersome. Therefore, embracing cumbersomeness for the sake of completeness, I synthesize the above discussion in the following working definition: hyperbole is a vivid form of expression that, in light of the world knowledge and expectations shared by the interlocutors regarding the extra-textual referent of the subject matter, is intentionally and recognizably more extreme than the situation warrants or is justified in order to convey or steer emotion and volition more effectively.

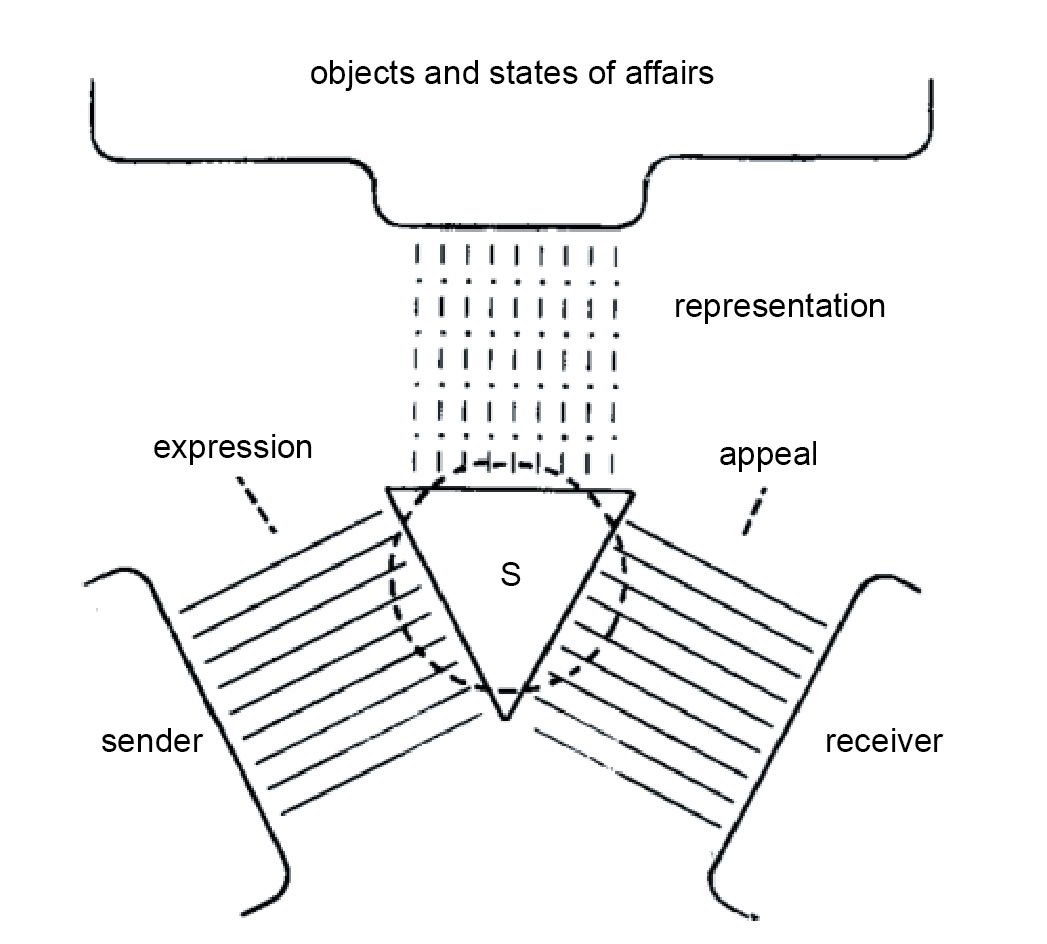

This definition aligns the Karl Bühler’s “Organon Model of Language” illustrated by fig. 1 (Bühler 2011, 35), with which he shows the three semantic functions of a complex language sign: representation, expression, and appeal (Bühler 2011).18 According to Bühler, the speaker (“sender”) expresses a representation of an extra-textual referent (“objects and states of affairs”) through a linguistic sign (“S”) in order to appeal to the hearer (“receiver”) and direct their “inner or outer behaviour” (Bühler 2011, 35).19

Fig. 1. Karl Bühler’s “Organon Model of Language.” Used with permission from John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.164.

For example, suppose my wife and I are in our living room, and she says, “It is so hot here!” This linguistic symbol states a fact about the current state of affairs, thus fulfilling the representational function of language. It also reflects my wife’s inner state of discomfort, thus fulfilling the expressive function. But she is not only stating a fact and expressing her feelings; she wants me (the receiver) to act about it, by turning on the fan or opening a window. So, the linguistic sign is also fulfilling the appellative function.

In the above working definition of hyperbole, the representational function is covered by the “extra-textual referent of the subject matter.” The expressive function is covered by the adjective “vivid” and the adverb “intentionally.” The appellative function is covered by the adverb “recognizably” as well as by the purpose to “convey or steer emotion and volition.” Besides, all this interaction is mediated through “the world knowledge and expectations shared by the interlocutors” expressed through the linguistic sign (“S”).

Identification

Having defined hyperbole, I will now proceed to present a methodology for identifying and interpreting it. Here, Cruise has made a significant contribution by gathering information from linguistics and biblical studies and synthesizing a “decision-making apparatus” for detecting hyperbole (Cruise 2017, 180). His methodology is based mainly on Robert H. Stein’s ten rules for recognizing hyperbole in Scripture (Cruise 2017, 180; Stein 2011, 177–88). By reworking those rules in combination with the six defining characteristics of hyperbole, Cruise breaks them down into three types of criteria: logical, rhetorical, and linguistic (Cruise, 2018, 92–93).20

First, Cruise lists four logical criteria that arise from the marks of nonveridicability and intentionality: (1) the statement is literally impossible; (2) the statement conflicts with what the speaker says or does elsewhere; (3) the statement conflicts with other passages of Scripture; and (4) the statement, if literally fulfilled, would not achieve the desired goal (Cruise, 2018, 92–93).

Second, Cruise lists three linguistic criteria that arise from the distinguishing marks of gradability and modulation: (5) the statement uses universal language; (6) the statement uses extreme case formulations, intensification or imaginative language; and (7) the context shows evidence of hyperbole (Cruise 2018, 93).21

Third, Cruise lists three rhetorical criteria that arise from the distinguishing marks of gradability, subjectivity, and discrepancy: (8) the context gives evidence of a rhetorical situation involving persuasion; (9) the context shows evidence of amplification; and (10) the statement may be vertically scaled (Cruise 2018, 93).

Applying this methodology can be aided by a formal classification of typical hyperbolic forms and linguistic clues. Claridge (2011, 46) seeks to described how hyperbole is realized in discourse and draws from Harry Spitzbardt (1963, 277–286) a list of categories that can help in identifying simple hyperbole:

- numerical hyperbole (1,000%)

- words of hyperbolic nature:

- nouns (ages) [for example, I learned that ages ago]

- adjectives (colossal) [for example, You made a colossal mistake]

- adverbs (astronomically) [for example, My bill was astronomically high]

- verbs (die) [for example, I would die to own one of those]

- simile and metaphor ([to run from the] cross as the devil)

- comparative and superlative degrees (in less than no time)

- emphatic genitive (the finest of fine watches)

- emphatic plural (all the perfumes of Arabia, Shakespeare)

- whole sentences (he is nothing if not deliberate)

Cruise also provides a list of hyperbolic forms used for both quantitative and qualitative hyperbole with numerous Old Testament and New Testament examples for each form. Table 1 is a summary and adaptation of those categories (Cruise 2017, 199–203).

| Quantitative Hyperbole | Qualitative Hyperbole |

|---|---|

| Lifetime: | Universal statements/generalizations |

| forever | Idealizations |

| Numerical: | Fertility |

| factor of 2 | Prowess in battle |

| factor of 7 | Righteousness/perfection |

| factor of 10 | Love |

| factor of 100/1,000/10,000 | Hate |

| Universal language: | Self-deprecation |

| all, every, none | Dead man |

| Size (extent): | Contempt/disdain/scorn |

| full of/filled | Boasting |

| infinite magnitude | Skill |

| sand | Emotions |

| dust | Impermanence |

| stones | Crying |

| water | Accusations |

| dew | Judgment |

| hairs | Mockery/ridicule |

| stars | Nakedness |

| Size (dimensions): | Other: |

| height/length/width/depth | joy/misery/threat/salvation/etc. |

| Time: | |

| night and day |

Table 1. Charles Cruise’s “The Form of Hyperbole in the OT.”

While the classifications shown in table 1 are not comprehensive, when coupled with the methodological considerations at the first part of this section, they do serve as helpful guidelines for the task of identifying and interpreting hyperbole with greater objectivity and will serve now as a tool to evaluate Longman and Walton’s claims about hyperbolic language in the FN.

Testing the Arguments for Hyperbole in the Flood Narrative

In this section, I will apply the foregoing discussion on the definition and methodology for identifying hyperbole, submitting each of Longman and Walton’s arguments presented in the first section of this paper to the three sets of criteria: logical, linguistic, and rhetorical.

Testing the Argument Concerning Pervasive Non-Order

The expression on which Longman and Walton base their first argument for hyperbole is “every intent of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually” (Genesis 6:5), coupled with the additional details about the wickedness of the Flood generation in Genesis 6:11–12 and the description of Noah’s character in Genesis 6:9.

Logical Criteria

According to the logical criteria for identifying hyperbole, Longman and Walton would have to be able to prove that (1) God’s evaluation is literally impossible, (2) that it conflicts with God’s statements about the extent of human wickedness elsewhere, (3) that God’s affirmation conflicts with other Scripture, and (4) that God’s assessment would not achieve the desired goal if literally true.

Concerning the first logical criterion, Longman and Walton’s main objection to a literal interpretation of God’s statement Genesis 6:5 is that those who take it literally cannot explain the descriptions of Noah’s righteousness in Genesis 6:9 after such a universal description of wickedness. However, this a problem only if one makes an atomistic reading of the text that does not allow for an author to make universalistic statements followed by exceptions, as if the exceptions would make the generalized statement false when taken literally. A clear example of this, given by Jesus himself (Matthew 12:5), is that the exception for priestly work on the Sabbath (Numbers 28:9–10) did not annul the universalistic prohibition of work on the Sabbath (Exodus 20:10).22

Walton, in his earlier commentary on Genesis, avoided this atomistic reading and argued against a hyperbolic understanding of Noah’s righteousness, suggesting that contextually it should be understood not in absolute terms but “in comparison with the people of his time” (Walton 2001, 311). That Noah’s righteousness and blamelessness was not absolute is clear from the episode of his drunkenness after the Flood (Genesis 9:21). But he does display a righteous conduct in the FN by believing God, obeying His commands (Genesis 6:22; 7:5), and offering sacrifice at the end of the Flood (Genesis 8:20).

Longman and Walton’s argument also ignores that the statement about Noah’s character is preceded by the affirmation that “Noah found favor in the eyes of Yahweh” (Genesis 6:8). The order of the text is important. Noah did not earn God’s favor through a righteous and blameless behavior.23 He was righteous (צַדִּיק) and blameless (תָּמִים) because he found favor in the eyes of Yahweh (Hamilton 1990, 276; Longman 2016, 116–17). This conclusion is supported by Carol Kaminski’s observation on the broader toledot structure of Genesis, where “favor” concludes the toledot of Adam and “righteousness” begins the toledot of Noah. She remarks, “it is favour that concludes the Toledot of Adam (5:1–6:8) and it is divine favour that provides a bridge between the history of humanity and the flood story. It is not insignificant that Noah’s finding favour in 6:8 precedes the statement about his righteousness in 6:9” (Kaminski 2014, 20). Thomas A. Keiser further nuances Kaminski’s argument by noting that while the insertion of toledot at 6:9 signals a structural segmentation of the narrative and indicates “a separation between the ideas of righteousness and finding favor,” the “conceptual flow of the narrative” points to a connection between the two concepts (Keiser 2019, 201).

As for the second logical criterion, no conflict with God’s affirmations about human depravity in other places can be found. In the near context, it has already been pointed out that in a proper, holistic reading of the text, stating an exception does not contradict the literal truth of a preceding universalistic statement. In a wider context, God’s evaluation in Genesis 6:5 finds resonance with His statement after the Flood that “the intent of man’s heart is evil from his youth” (Genesis 8:21). The difference between God’s statements about the level of human depravity before and after the Flood is the latter statement lacks the universalistic terms “every” (כֹּל) and “only” (רַק). This difference corroborates a literal reading of the pre-Flood description of human depravity, as the absence of the universalistic qualifiers in the post-Flood description can be explained considering the complete elimination of those that made the pre-Flood description appropriate.

Seen in this light, God’s pre-Flood evaluation is not just the likely best “description of total depravity” (O’Connor 2018, 110; Walton 2001, 207; cf. Wenham 1987, 144). It is more than that. It is a description of total depravity manifested at an “unprecedented level” (Longman and Walton 2018, 38) that warranted a universalistic statement that is best understood literally and that rightly justified a global flood.

Concerning the third logical criterion, the description of human depravity accords in essence, though not necessarily in degree, with the other Scripture, such as Genesis 8:21, Psalm 14:1–3 and Jeremiah 17:9–10 (Wenham 1987, 144). Waltke and Fredericks (2001, 118) also remark that the “vivid portrayal” of the situation described here “portends the end of history with the coming of Christ (Luke 17:26–27; 18:8; 2 Timothy 3:1–5; Revelation 20:7–10, and Jewish apocalyptic literature),”24 when again, in response to deep and widespread manifestation of human depravity, God will unleash worldwide catastrophic judgment on mankind.

Regarding the fourth logical criterion, it is appropriate to affirm that a literal understanding of the description of human depravity in Genesis 6:5 does achieve the desired goal of the passage which is to explain the God’s rationale for His decision for an all-encompassing measure to the problem He identified. Hamilton cogently argues that Genesis 6:5 shows that “The God of the OT never acts arbitrarily” and that, unlike the gods of mythological flood accounts, Yahweh decides to send the Flood based on “a clear-cut moral motivation” (Hamilton 1990, 273). Nahum M. Sarna, though not arguing for the historicity of the narrative, insightfully observes that “The fact that only Noah was saved because only he was righteous implies clearly that the rest of his generation was individually evil and that therefore, what appears to be collective retribution on the part of God is, in the final analysis, really individual” (Sarna 1966, 52, emphasis added).

Therefore, a literal understanding of God’s universalistic description of human depravity, coupled with the description of Noah’s character, does accomplish the purpose of explaining why God decided to destroy all humanity and why only Noah and his family were saved.

Linguistic Criteria

Concerning the linguistic criteria for identifying hyperbole, Longman and Walton’s argument is more at home and satisfies criteria (5) and (6) as listed in the methodological section of this paper. First, the text does use universalistic terms such as “every” (כֹּל) and “only” (רַק). Second, the description is extreme and vivid as it describes the “intent of the thoughts of [man’s] heart” (יֵצֶר מַחְשְׁבֹת לִבּוֹ). The description is complemented in Genesis 6:11–12, where universalistic and extreme language is seen again in the phrases “the earth was filled with violence” (וַתִּמָּלֵא הָאָרֶץ חָמָס) and “all flesh” (כָּל־בָּשָׂר).

However, when it comes to criterion (7), the context of the passage is appropriate for taking universalistic terms at face value, instead of evidencing hyperbole. First, in its wider context, the passage in inserted within the first division of book of Genesis (1:1–11:26), which is marked by the first five out of ten toledot subdivisions of the book.25 It is widely recognized that the first part of Genesis (1:1–11:26) deals with the so-called primeval history, which is universal in scope, while the second part of Genesis (11:27–50:26) deals with the so-called patriarchal history, which is more particular in scope, focusing on Abraham and his descendants. So, it is not surprising that a passage in the context of universalistic primeval history will appropriately employ universalistic terms to describe an event that is universal in scope.

Therefore, even though Longman and Walton’s argument satisfies some of the linguistic criteria for hyperbole, the context of the passage indicates that they do not serve as sufficient evidence to interpret the description of pervasive non-order as hyperbolic. If the simple presence of universal and extreme language were sufficient to establish a statement as hyperbolic, it would be impossible to make statements that are legitimately and literally universal (including a statement such as “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” in Romans 3:23 or that in reference to Christ “all things have been created through Him and for Him” in Colossians 1:16).

Rhetorical Criteria

According to the rhetorical criterial, in order for the description of pervasive non-order to be classified as hyperbole Longman and Walton would need to demonstrate (8) that the context gives evidence of a rhetorical situation (especially one involving persuasion/dissuasion), (9) that the context shows evidence of amplification (via intensifiers or downtoners), and (10) that the statement can be vertically scaled (that is shows gradability).

Concerning the first rhetorical criterion, it must be noted that the description of human depravity is found in the context of a divine soliloquy or monologue (Genesis 6:3–7) (O’Connor 2018, 110; Skinner 1930, 151). It is not until later that Yahweh will engage in dialogue and communicate His intention, His motive, and His instructions to Noah (Genesis 6:13–21). As discussed above, hyperbole is found in rhetorical situations in which the speaker desires to convey his emotion and volition to the hearer in order to steer the hearer’s emotion and volition. This is not the situation here. And as Roger Lapointe (1970, 180) cogently argues,

The speaker who soliloquizes talks to himself and consequently does not try to fool anyone; he may, of course, deceive himself, but this possibility does not seem to be taken into consideration by the Bible in dealing with God. Moreover, what the speaker says will always express faithfully what he thinks, since he is supposed to ‘think’ the very words of the text. In this way, the divine monologues provide for Revelation [sic] a basis of unsurpassable surety.26

As for the second rhetorical criterion, it is possible to argue that amplification is achieved in the description of pervasive non-order by means of crescendo, alliteration, and assonance.27 Crescendo is seen in the intensification from mankind’s “great evil” (רַבָּה רָעַת הָאָדָם) to “only evil” (רַק רַע). Alliteration and assonance are seen in the expression “only evil” (רַק רַע), in which two short words with the same initial and of similar sound are piled up (Leupold 1974, 1:260). However, given the lack of a context of a rhetorical situation, this intensification is best seen as reflecting the transition from the relatively restricted locus of manifestation of evil, “on the earth” (בָּאָרֶץ), to the unrestricted locus of machination of evil, “every intent of the thoughts of his heart” (וְכָל־יֵצֶר מַחְשְׁבֹת לִבּוֹ).

Regarding the third rhetorical criterion, it can be said that the statement regarding human depravity in Genesis 6:5 can be vertically scaled down. Longman and Walton do offer a proposal of a scalar mitigation of the expression by arguing that it conveys the fact that “evil had reached an unprecedented level” (Longman and Walton 2018, 38). However, the fact that the expression can be mitigated along a vertical scale does not mean it should be. As previously demonstrated, the context of the statement describes a universal situation and does not evidence a rhetorical situation that could justify that universal description should be interpreted hyperbolically.

Preliminary Conclusion

After testing Longman and Walton’s first argument, it has become evident that it can hardly be argued that the description of pervasive non-order should be interpreted hyperbolically. Out of the ten criteria to which their argument was subjected, it only satisfied four (linguistic criteria 5 and 6, and rhetorical criteria 9 and 10), none of which were logical criteria. Even those linguistic and rhetorical criteria that were satisfied do not necessitate a hyperbolical interpretation because of the lack of a context that provides evidence of hyperbole and the lack of an appropriate rhetorical situation.

Testing the Argument Concerning the Dimensions of the Ark

The gist of Longman and Walton’s second argument is that the dimensions of the ark found in Genesis 6:15 “lead us to believe that they are hyperbolic numbers” (Longman and Walton 2018, 38). However, the two questions that remain unanswered are: (1) How so? and (2) Do they?

Related to this argument is the alleged logistical problem of transporting and caring for about 42,000 animals. I will not take too long in dealing with this part of the argument in the subsections below. Suffice it to say here that this supposed problem is not derived from any datum in the biblical text, but on the assumption that “the 21,000 species of amphibian, reptile, bird, and mammal had to be represented on the ark” (Morton 1997, 241; cited in Walton 2001, 323). This assumption is based on two other unstated (and baseless) assumptions: (1) that today’s number of species in those animal classifications is the same as at the time of Flood; and (2) that the Hebrew word translated as “species” or “kind” (מִין) is equivalent to the modern taxonomical classification of species.

Concerning the first assumption, young-earth creationists do believe in variation of species within the limits of the same “created kind,” so that the number of species today is expected to be significantly larger than at the time of the Flood.28 As for the second assumption, it is necessary to exercise caution in seeking to establish an equivalence between the biblical concept of kind and modern taxonomical classification.29 However, details of the biblical text (like the ability to reproduce within a kind) and the ongoing discussion on the concept of “created kinds” (baraminology) suggest that the biblical concept of kind is flexible and can refer to a higher orders of taxonomical classification such as genus, family, or even order. If that is the case, the number of animals necessary to preserve the original created kinds of land animals and birds would be much smaller than normally assumed by the critics of the traditional interpretation of the FN.30

I will now turn my attention to the claim that the provided dimensions of Noah’s Ark suggest that they are hyperbolic numbers to subject that claim to the methodological criteria for identifying hyperbole.

Logical Criteria

According to the logical criteria for identifying hyperbole, Longman and Walton would have to demonstrate that (1) the dimensions of the Ark are literally impossible, (2) that they conflict with God’s statements elsewhere, (3) that they conflict with other Scripture, and (4) that, if literally true, the dimensions of the Ark would not achieve the desired purpose. As for the first logical criterion, Longman and Walton base their argument on two difficulties that they find “hard to imagine” being overcome: (1) the fact that there was no boat in antiquity of the size of Noah’s Ark; (2) that Noah and his family could not accomplish the task of building such a huge vessel (Longman and Walton 2018, 38–39).

The first difficulty can be characterized as an argument from silence. The affirmation that “there has never ever been a wooden boat nearly as large as the ark” (Longman and Walton 2018, 39) is––ironically ––a sweeping overstatement given the limited nature of archaeological evidence,31 especially when dealing with the difficulties of subaquatic archaeology. It is safer and more responsible to affirm that never has a wooden boat the size of the ark been recovered or described in the extant literature. Lionel Casson in his book on ancient seamanship history shows that, as early as the third millennium BC there is evidence of wooden riverboats in Egypt “running up to 150 feet in length,” which is one third the length of the Ark (Casson 1995, 17). He also describes an early second millennium BC Egyptian cargo barge measuring “well over 200 feet long and 70 feet wide,” which is roughly half the length of the Ark but proportionally almost double its width (Casson 1995, 17).

Longman and Walton’s argument assumes too much. It assumes that the development of technology is always linearly progressive, so that technology cannot be lost due to unknown circumstances and need to be recovered later from a less advanced level. This especially true in the case of major societal disruptions or collapse of civilizations. A remarkable example of this is the case of Roman concrete, which even today continues to be studied to gain insight into its chemical composition and methods for developing better concrete formulations (Elsen, Cizer, and Snellings 2013; Seymour et al. 2023). Also, if granted that there were no comparable wooden boats in antiquity, it assumes that the reason for that must be lack of technology, instead of simply lack of need or demand, or perhaps a preference for vessels that are smaller, safer, and easier to build and to maintain. Besides, the unprecedented size of the Ark can be explained in light the unprecedented purpose for its construction: to preserve life from an unprecedented cataclysmic judgment occasioned by an unprecedented level of wickedness (Leupold 1974, 1:273).

The second difficulty presented by Longman and Walton as support for their argument for hyperbole also assumes too much. It assumes, for example, that only Noah and his family were involved in the task. The text is silent about this, but Noah had relatives who were alive at least during part of the period in which he was building the Ark (like Methuselah, Lamech, and probably many brothers, cousins, and uncles), who could have helped him in this project. Also, Noah could have hired laborers for specific parts of the work. Again , there is nothing in the text about it, but also there is nothing in text against it.

Longman and Walton also suggest that Ken Ham’s project, the Ark Encounter, instead of confirming the feasibility of Noah’s Ark, actually raises questions about it. They specifically call attention to things that Noah did not have access to but were used in the building of the Ark Encounter, like “the power tools, the cranes, the steel scaffolding that keeps the boat from cracking apart, and the tens if not hundreds of skilled workers with their power tools who built this boat” (Longman and Walton 2018, 39).

In response, it must be noted that the Ark Encounter took a little over six years from contract to completion to be built (the actual construction took less than two years),32 while Noah may have taken between 55 and 75 years, considering that he received the command and instructions to build when his three sons were already married (Genesis 6:18).33 So, Noah would have at least ten times––but likely more than 30 times––as much time to build the Ark than the Ark Encounter did. Besides, Noah did not need contracts and government compliance, he did not need to build concrete structures, electrical wiring, modern bathrooms, sound effects, exhibits, and many other requirements of modern building that the Ark Encounter had to incorporate and comply with for its purposes (cf. Bielo 2018).

Another important point to consider regarding this supposed difficulty is regarding the amount of instructions God gave to Noah. Claus Westermann rightly points out that the pieces of information that are possible to glean from the text “are not sufficient to permit a detailed reconstruction” of the ark (Wenham 1987, 172; Westermann 1984, 418). The brevity of the instructions in the text, however, should not lead one to conclude that the information we are given was all that Noah received (Leupold 1974, 1:272). Brian Peterson concurs and argues that “if God gave Noah the plans (cf. Exodus 26:30), as is implied, then it is very likely that Noah’s Ark was possible. Indeed, living in the region of ancient Babylon between the Euphrates and Tigris would have made Noah privy to shipbuilding techniques” (Peterson 2022, 81).34

Finally, it must be added that in contrast with the impossible descriptions of the boat in the Epic of Atrahasis, which is round, and in the Epic of Gilgamesh, which is cubic or ziggurat-shaped, the dimensions and proportions of Noah’s Ark are logical, plausible, and actually seaworthy (Hamilton 1990, 282; Mathews 1996, 365; Waltke and Frederick 2001, 135–36). This point is agreed upon even by Longman, which is a notable inconsistency with his and Walton’s arguments (Longman 2016, 117). The realistic portrayal of Noah’s Ark in comparison to its ANE parallels is further enhanced by the fact that the boat in the Epic of Gilgamesh has four times the volume of Noah’s Ark and yet is said to have been completed in only seven days (Longman 2005, 83). But in arguing for a hyperbolic understanding of the dimensions of Noah’s Ark, Longman and Walton cite Irving Finkel’s study that points out that despite the shape and dimensions of Noah’s Ark being different from those of the epics of Atrahasis and Gilgamesh, the floor space of them all is only slightly different (Finkel 2014, 314; Longman and Walton 2018, 61n1). Suffice it to say that it is strangely convenient for their argument that they use only two dimensions in their comparison and leave out the aforementioned fact that Uta-napishti’s boat had four times the volume of Noah’s Ark.

Concerning the alignment of Longman and Walton’s argument with criteria (2) and (3), there is no basis in the immediate or wider canonical context to affirm that the description of size of the Ark conflicts with God’s statements or other statements of scripture. In fact, 1 Peter 3:20, though not a direct proof, supports taking the description in Genesis 6:15 at face value. Peter’s description of God patiently waiting “during the construction of the ark” suggests that it took a long time to build the ark (perhaps an allusion to the 120-year grace period of Genesis 6:3), thereby, aligning with a literal understanding the boat was indeed very large.

Regarding logical criterion (4), God’s desired goal was that the ark would be large and strong enough to save Noah with his family and carry a large number of animals (Genesis 6:18–20). It is not logical to affirm that if the dimensions of the Ark are literally understood, this goal would be defeated. In fact, just the opposite is the case: a literal understanding of the dimensions of the Ark perfectly aligns with the purpose for which it was designed by God (Leupold 1974, 1:273).

Linguistic Criteria

According to the linguistic criteria for identifying hyperbole, Longman and Walton would have to be able to prove that (5) the description of the dimensions of the Ark uses universal language; (6) that it employs extreme and imaginative language; and (7) that the context of the description shows evidence of hyperbole.

Regarding the first linguistic criterion, the description of the ark itself is devoid of universalistic terms that are used in other parts of the FN. To be sure, the word “all” (כֹּל) is applied to the listing of the animals Noah is supposed to transport in the ark (Genesis 6:19–20) and to the food supplies that Noah is supposed to bring to the ark (Genesis 6:21), but it is not applied to the dimensions of the Ark. Even if that would be the case, it would still not be a sufficient condition to classify the description as hyperbolic. I reaffirm: if the simple presence of universal and extreme language were sufficient to establish a statement as hyperbolic, it would be impossible to make statements that are legitimately and literally universal (for example, Matthew 28:18; Romans 3:23; Colossians 1:16).

As for the second linguist criterion, no extreme or imaginative terms are used to describe the Ark. As Burlet aptly notes, “The boat is not classified within canonical literature as being the ‘biggest,’ ‘fastest,’ ‘smallest,’ or ‘strongest’ ship ever made or even a ‘big’ ‘fast,’ ‘strong,’ or ‘small’ ship” (Burlet 2024, 156). Nor even as a “ship of Tarshish” (1 Kings 10:22; Psalm 48:7; Isaiah 2:16; 60:9; Ezekiel 27:25) or a “mighty ship” (Isaiah 33:21). The biblical description is, indeed, remarkably modest. The absence of such superlative qualifiers both in the FN and in other passages of Scripture alluding to Noah’s Ark (Matthew 24:37–39; Luke 17:26–27; Hebrews 11:7; 1 Peter 3:20) argue against taking the description of Noah’s Ark as hyperbolic.

Rhetorical Criteria

According to the rhetorical criteria for identifying hyperbole, Longman and Walton would have to demonstrate (8) that the context of the description of the dimensions of the ark evidences a rhetorical situation that is appropriate for hyperbole; (9) that the context also evidences amplification through intensifiers or downtoners; and (10) that the dimensions of the ark may be vertically scaled.

Concerning the first rhetorical criterion, it can be said that the description of Ark in found in a rhetorical situation in which God is expressing His volition to Noah and seeking to steer Noah’s volition towards obeying His command and following His instructions. Does this rhetorical situation favor seeing God’s communication as hyperbolic? In an atomistic reading of the text, perhaps. But in a contextual reading, just the opposite seems to be the case. According to McCarthy and Carter one of the characteristics of the rhetorical situations involving hyperbole that needs to be observed is “listener take-up: the listener reacts with supportive behaviour such as laughter or assenting back-channel markers and/or contributes further to the counterfactuality, impossibility, contextual disjunction, etc.” (Cruise 2017, 134; McCarthy and Carter 2004, 162–63). However, when the text describes Noah’s response to God’s instruction it says with emphatic repetition, “Thus Noah did; according to all that God had commanded him, so he did” (Genesis 6:22; cf. 7:5). If God desired to communicated hyperbolically with Noah about His evaluation, intention and instructions, He did so poorly, since the perlocutionary effect of God’s locution to Noah was that he proceeded to act exactly according to God’s instructions. According to Seneca’s classical discussion on the rhetorical purpose of hyperbole,

Whenever you lack confidence in those to whom you are giving orders, you should demand of them more than is necessary in order that they may perform all that is necessary. The set purpose of all hyperbole is to arrive at the truth by falsehood. . . . Hyperbole never expects to attain all that it ventures, but asserts the incredible in order to arrive at the credible. (Seneca 1935, 508–11 §7 .23.1–2)

God does not show “lack of confidence” in Noah. In fact, he is selected for this mission because, having been enabled by God’s grace, Noah has shown himself to be trustworthy in his walk with Him.

As for the second rhetorical criterion, the description of the dimensions of the ark shows no distinguishing marks of amplification, such as incrementation, comparison, inference, or accumulation.35

Regarding the third rhetorical criterion, Longman and Walton do not offer a proposal of mitigation of the dimensions of the Ark in order to give a realistic view of its size. They do suggest that the concept of “academic arithmetic” could be at play here as it was practiced in the ancient world. By academic arithmetic, they mean that the dimensions could be idealized and “not relative to the actual size,” thus defying proposals of mitigation (Longman and Walton 2018, 75–76).

There have been suggestions of mitigation of the dimensions of the Ark by dividing them by some factor. For example, Raphael Patai, who holds that the measurements of the Ark are “a fanciful exaggeration,” suggests that a late author taking as reference ships available at his time “multiplied the measurements of the ships he saw by a round number, such as seven, or ten; then, ignoring the units under ten, he arrived at the arbitrary sizes of 300, 50, and 30 cubits for the length, breadth, and height of Noah’s Ark” (Patai 1998, 5, emphasis added). Umberto Cassuto sees the numbers as part of the “poetic and exalted character” of the narrative and notes that “the number 300 is one of the round figures in the sexagesimal system,” that the number 50 is “half of one hundred, one of the basic numbers of the decimal system,” and that the number 30 is “half of sixty, the fundamental number of the sexagesimal system” (Cassuto 1964, 62–63). Likewise, Carol Hill suggests that “it may be that the dimensions of the Ark were never converted from a sexagesimal system into a decimal-based numbering system. If one arbitrarily divides the ark dimensions by either ten or six, one comes up with a size more compatible with boats known to have existed in Jemdet Nasr time” (Hill 2001, emphasis added).36

What is striking and highly problematic about the above proposals is their patent arbitrariness. Why divide by seven, by ten, or by six? Why mix the sexagesimal and decimal systems? Why should units under ten be ignored? Critiquing Patai’s proposal in a way that can be applied to the others as well, Burlet correctly points out his failure to explain “why a scribe would have selected those figures, in particular, from among any other number, such as three, five, twelve, or forty (why not!) which are also known to contain symbolic meanings” (Burlet 2022, 117). In sum, Longman and Walton do not propose a mitigation of the dimensions of the Ark and the proposals offered by Patai, Cassuto, and Hill are all patently arbitrary.

Preliminary Conclusion

After testing Longman and Walton’s second argument, it has become evident that the case for hyperbolic interpretation for the dimensions of Noah’s Ark is even weaker than their first argument as it fails to satisfy any of the logical, linguistic, and rhetorical criteria. I concur with Burlet when he concludes that “the book of Genesis shows acute moderation and refrains from exaggeration in its depiction(s) of the design and dimensions of Noah’s Ark” (Burlet 2024, 160).

Testing the Argument Concerning the Mechanisms and Extent of the Flood

To recall the gist of Longman and Walton’s third argument, they claim that both the mechanisms of the Flood (Genesis 7:11), which, in their view, reflect “an ancient cosmology,” and the height of the Flood waters covering “all the high mountains under all the heavens” (Genesis 7:19–20) would have been understood by the original audience as hyperbole (Longman and Walton 2018, 40–41). They also claim that the repeated use of the Hebrew word translated as “all” (כֹּל) is part of a “universalistic rhetoric” that is “in keeping with the use of hyperbole” (Longman and Walton 2018, 69–70).

Logical Criteria

According to the logical criteria, Longman and Walton would need to be able to prove that (1) the mechanisms and extent of the Flood are literally impossible, (2) that they conflict with God’s statements elsewhere, (3) that they conflict with other Scripture, and (4) that, if literally true, the mechanisms and extent of the Flood would not achieve the desired purpose.

As for the first logical criterion, Walton, in his commentary on Genesis, raises the issue and cites scholars who see a problem with the Flood waters reaching up to 17,000 ft to cover Mount Ararat (Walton 2001, 322, 324, 326).37 The principal challenges leveled against the traditional view are: (1) explaining where the water came from; (2) explaining where the water went at the end of the Flood; (3) explaining how people and animals could breathe at such elevation; (4) explaining how the dove could fly down and back up 17,000 ft.

The main problem with the above objections is that it they engage in circular reasoning, because they unwittingly assume that the Flood was not global in order to point to a problem with the global flood view. How so? The objections point to the current height of Mount Ararat (and other much higher mountains today) to argue that there was not enough water to cover all the high mountains of the pre-Flood world. In doing so, they assume that there was not significant change in the earth’s topography between the pre-Flood era and today (Waltke and Fredricks 2001, 133n34), which is tantamount to assuming that the Flood was not global.

However, if the Flood was global and catastrophic as Genesis describes it, then we should expect that it would have greatly altered the earth’s topography and we should not assume that it would have to cover today’s Mount Ararat, Mount Everest, or any of today’s mountain ranges for that matter. Instead, it is more logical to think that a flood of such catastrophic proportions would have massively contributed to the formation of today’s mountain ranges through its processes (seismic disturbances, volcanic activity, and sedimentary depositions). Besides, we should not lose sight of the fact that the Flood is described in the biblical narrative as a divinely wrought supernatural event and that objections to its feasibility and alternative explanations often betray naturalistic presuppositions.

Regarding the second and third logic criteria, it is not possible to point out any contradiction with anything in the near context of the book or in the wider context of Scripture that would justify taking the mechanisms and extent of the Flood as hyperbolic. In fact, later authors of Scripture understood the Flood as a worldwide historical judgment and used it as a paradigm for prophesying the coming of a worldwide eschatological judgment (Matthew 24:37–39 [“all”]; Luke 17:26–27 [“all”]; 1 Peter 3:20–21 [“few, that is eight persons”]; 2 Peter 2:5 [“world” and “Noah . . . with seven others”]; 3:6–7 [“world”]) (von Rad 1973, 129–130). In those passages, Jesus and Peter confirm the universality of the Flood and appropriately use it as the grounds for their confidence in a coming global judgment.

Another passage with possible implications for understanding the mechanisms and extent of the Flood is Psalm 104:5–9, which describes the water of the deep covering the earth and “standing above the mountains,” then being rebuked and contained to established boundaries through seismic processes, so that “they will not return to cover the earth.”38 To be sure, it is widely recognized that the majority of commentators interpret Psalm 104:5–9 as referring exclusively to the third day of the Creation Week (Barrick 2018, 95; Seely 1999).39 However, William Barrick, demonstrates that the “structural, grammar, and vocabulary” of Psalm 104:5–9 have “greater affinity to Genesis 7 than to Genesis 1” (Barrick 2018, 101).40 He points to notable exceptions such as Charles Spurgeon, James M. Boice, and J. A. Alexander, who saw the connection to the Flood (Barrick 2018, 98–99).41 Others like J. J. Stewart Perowne (1989, 2:239), often cited by Spurgeon, and a growing number of newer commentators including Geoffrey Grogan (2008, 174), Willem A. VanGemeren (2008, 765), John Goldingay (2008, 185n32), Daniel Estes (2019, 274),42 and Christopher Ash (2024, 53) recognize features in the passage that make it possible to see a reference to both events, especially in light of Psalm 104:9. Noel Weeks concedes this point by observing that “Psalm 104 may be about creation, but it was written post-Flood, and that shapes its language” (Weeks 2006, 290).

Concerning the fourth logical criterion, if one considers the purpose of the Flood as an event, it does not seem logical to think that a literal understanding of the mechanisms and extent of the Flood would not fulfill God’s stated purpose to destroy all life on the earth and the surface of the earth itself.43 Later, under the appropriate section, I will also consider the rhetorical and theological purposes of the FN as a literary piece.

Linguistic Criteria

According to the logical criteria, Longman and Walton would need to demonstrate that (5) the description of the mechanisms and extent of the Flood employ universal language, (6) that it uses extreme or imaginative language, and (7) that the context shows evidence of hyperbole.

Concerning the rhetorical criteria (5) and (6), the description of the extent of the Flood does employ universal and extreme language. The word “all” (כֹּל), which occurs 70× in the FN, often modifies nouns that describe the Flood’s reach and impact for example, all the mountains, all animals, and all mankind).44 It could also be argued that the description of the mechanisms of the Flood is universalistic since it employs a merism (that is, “the fountains of the great deep” [תְּהוֹם] vs “the floodgates of the sky” [הַשָּׁמַיִם]): using two extreme opposites to express the idea of totality (Genesis 7:11). However, as demonstrated previously in the discussion of their first argument, when it comes to criterion (7), both the wider and immediate contexts of the passage are appropriate for taking universalistic terms at face value, instead of evidencing hyperbole.

Kenneth Mathews, who briefly entertains the possibility of hyperbole, sees in the insistence on the use of universalistic qualifiers not as evidence for hyperbole, but for a literal understanding of the extent of the Flood. He argues,

An alternative understanding is that the comprehensive language of the text is hyperbolic or a phenomenological description (from Noah’s limited viewpoint), thus permitting a regional flood (see 7:17–20 discussion). And “earth” can be rightly rendered “land,” again allowing a limited venue. This kind of inclusive language for local events is attested elsewhere in Genesis (e.g., 41:54–57), but the insistence of the narrative on the encompassing character of the flood favors the literal understanding of the universal view. (Mathews 1996 , 365)45

It must be noted that the extent of the Flood is not described only with universalistic terms, but also with additional details that indicate that the universal and extreme terms should be taken at face value. For example, the expression “all the high mountains under all the heavens were covered” is supplemented by the information that “the water prevailed fifteen cubits higher, and the mountains were covered” (Genesis 7:19–20) (Waltke and Fredricks 2001, 140). Also, Genesis 8:3–5 says that 75 days after the Ark rested on the mountains of Ararat “the tops of the mountains appeared.” In his commentary on this passage, Walton recognized that the clarity of the details of Genesis 8:3–5 makes it difficult to argue against a global flood. Yet, as his remarks below show, he remained unconvinced:

If it were not for 8:3–5, an interpreter can easily claim that the face value of the text does not demand a geographically global flood. All of the other statements are compatible with a flood of the known populated world. Given the apparent clarity of 8:3-5, however, it is difficult to see how the Flood could be less than global if the waters reached a height of 17,000 feet. So how do we reconcile the apparent clarity of the text with the extremely difficult logistics? (Walton 2001, 326)

Another universalistic linguistic detail concerning which Longman and Walton take issue with the literal understanding of the extent of the impact of the Flood is the statement that “only Noah remained, and those that were with him in the ark” (Genesis 7:23). They argue that “if the text wanted to single out Noah (and those with him) as alone surviving” the Flood, it would have used the Hebrew particle רַק instead of אַךְ (Longman and Walton 2018, 70–71). hey assert that the regular functions of אַךְ are either asseverative (for example, “surely”) or adversative (for example, “yet”), instead of limiting/restrictive (for example, “only”), so the text is “vague about the human survivors” (Longman and Walton 2018, 71).

Such an assertion flies in the face of some of the most important studies on the similarities and differences between רַק and אַךְ in the last decades. For example, Stephen Levinsohn made a comprehensive study analyzing the meaning of these two particles in different positions in the clause. He concluded that, while both particles are limiters, רַק has an added countering function that אַךְ lacks (Levinsohn 2011). To be sure, אַךְ can be used in contexts where countering is present (such as Genesis 7:23), but when it does so it “does not emphasize the contrast,” but “limits or minimizes the contrast, often with the effect of strengthening another assumption” (Levinsohn 2011, 83, emphasis original).46 Additionally, van der Merwe, Naudé, and Kroeze (2017, 388–390 §40.8) classify the limitation function of אַךְ as “very frequent” and the equivalent to Longman and Walton’s asseverative function of אַךְ as “seldom” or “rare.” Van der Merwe, Naudé, and Kroeze classify both רַק and אַךְ as restrictive focus particles without substantial differences between the two (van der Merwe, Naudé, and Kroeze 2017, 388 §40.8, 445 §40.41).

It is important to observe that, despite the fact that van der Merwe, Naudé, and Kroeze have incorporated Levinsohn’s study in the second edition of their grammar, they still maintain, contra Levinsohn, that the two particles are near synonyms (van der Merwe, Naudé, and Kroeze 2017, 38n25; Levinsohn 2011, 105).47 Nevertheless, the fact remains that their classification of רַק and אַךְ as restrictive-focus particles agrees with Levinsohn’s classification of both of them as limiters. Though I favor Levinsohn’s analysis of these two particles, the main point of the foregoing discussion is that Longman and Walton’s point on the distinction of רַק and אַךְ rests on tenuous grammatical grounds and is––ironically!––highly overstated exactly on the point in which they are widely recognized as being similar (that is, in that they share the semantic value of restriction/limitation).

In this context, especially considering its position at the end of a sequence כֹּל (“all”), אַךְ is best understood as having its regular restrictive function in which Noah, his family, and the animals in the Ark are defined as an exceptive subgroup in relation to the previously defined larger group of people and animals destroyed in the waters of the Flood (Bandstra 2008, 423). Concerning Genesis 7:23, where אַךְ is used in a countering context, Levinsohn adds that “the effect of using אַךְ, rather than רַק, is to limit the survivors to just Noah and those with him in the ark, thus strengthening the assertion that every (other) living thing was ‘blotted out from the earth’” (Levinsohn 2011, 89).

Rhetorical Criteria

According to the logical criteria, Longman and Walton would need to demonstrate that (8) the context of the description of the mechanisms and extent of the Flood gives evidence of a rhetorical situation, (9) that the context of the description of the mechanisms and extent of the Flood shows evidence of amplification, and (10) that the description of the mechanisms and extent of the Flood can be vertically scaled.

As for the first rhetorical criterion, if one considers the rhetorical or theological purpose of the FN, instead of the purpose of the Flood event (discussed above), the message and significance of the Flood is more clearly expressed by a literal understanding than by a hyperbolical understanding. In this respect, Jean Francesco Gomes rightly questions,

If I understand them correctly, Walton and Longman argue that through a rhetorically global narrative of the flood, biblical authors aimed to convince their neighbors that God is not a local deity but a sovereign God who has control over the whole earth. I wonder whether that was a convincing argument at the time. What is the point of using an exaggeration to convince someone of the true God? Why would anyone believe that YHWH was a global deity if the evidence pointed in the local direction? (Gomes 2020, 367, emphasis added)

I would contend that, instead of helping, hyperbole defeats the rhetorical or theological purpose that Longman and Walton assign to the FN. Hardly anyone would be led to believe that Yahweh was the legitimate global deity on the basis of rhetoric that is not grounded on historical fact.

Concerning the second rhetorical criterion, it is possible to see some elements of amplification in the description of the mechanisms and extent of the Flood. One of the literary strategies of amplification employed in the FN is repetition with incremental addition of details, forming a kind of ascending terrace structure. This strategy is used before the waters of the Flood come and function to slow down the narrative and increase tension (Genesis 7:6–16). It is also used to describe the rise of the Flood waters in mounting waves of intensity, thus creating “a tumultuous scene of waters overtaking the earth” (Genesis 7:17–20) (O’Connor 2018, 125, 127; Waltke and Fredericks 2001, 140; Wenham 1987, 183).48 While this evidence of amplification could be seen as one possible indication of hyperbole, it is not out of step with a literal understanding of the extent and impact of the Flood. In fact, the literary artistry displayed in the composition is very appropriate to describe the climax of the global flood with the fulfillment of the purpose for which God sent it. The use of such rhetorical devices coupled with historical factuality would be a more powerful conveyor of the theological message of the Flood, than rhetoric in conflict with historical factuality.

Regarding the third rhetorical criterion, while the description of the mechanisms of the Flood is not stated in a way that can be vertically scaled, the description of the extent of the Flood’s reach and its impact can potentially be mitigated. The repeated occurrences of “all” could be scaled down to “many.” The expression “under all the heavens” could be downgraded to “in the entire region.” The word “earth” could be mitigated to mean “land” or “the known world.”

However, the problem of explaining how to scale down the information that the water rose 15 cubits higher than the mountains combined with the information from Genesis 8:5 that 75 days after the Flood mechanisms stopped and their tops appeared would remain unsolved. Besides, since both the wider and immediate contexts of the passage are appropriate for taking universalistic terms at face value and a literal understanding better fulfills the rhetorical and theological purpose of the FN, the main question is not whether the descriptions can be mitigated, but if they should be. To the latter question, the context and purpose of the FN indicate that the answer is no.

Preliminary Conclusion

After testing Longman and Walton’s third argument, it has become evident that the case for hyperbolic interpretation of the mechanisms and extent of the Flood is not as strong as it may initially appear. To be sure, their claims satisfy two of the linguistic criteria (universal and extreme language) and two of the rhetorical criteria (amplification and gradability). But on both counts, they fail to demonstrate (1) how the context justifies not taking the evidences of universal language and extreme language at face value, and (2) how rhetorical/theological purpose is better served by the hyperbolic rather than the literal interpretation. Finally, as with all previous arguments, this one also fails to satisfy any of the logical criteria.

Conclusion

This paper has demonstrated that the hyperbolic interpretation of the FN proposed by Longman and Walton is deficient. It lacks a clear, linguistically robust, and objective methodology guiding the construction of their arguments, indicating that their conclusions are more based on personal impressions or imagination and subjective feeling than on objective criteria. And when such a methodology is provided it lacks conformity with logical, linguistic, rhetorical criteria for identifying hyperbolic expressions. Therefore, Longman and Walton’s exaggerated claims should be considerably mitigated and their hyperbolic view of FN as a whole and resulting denial of global, catastrophic flood of Noah’s day should be rejected.

References

Abraham, Werner. 2011. “Traces of Bühler’s Semiotic Legacy in Modern Linguistics.” In Theory of Language: The Representational Function of Language by Karl Bühler. Translated by Donald F. Goodwin and Achim Eschbach, xiii–xlviii. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing.

Ark Encounter. “Noah’s Ark vs. the Ark Encounter: What’s the Difference.” https://arkencounter.com/blog/2019/03/28/noahs-ark-vs-ark-encounter-whats-the-difference/.

Ash, Christopher. 2024. The Psalms: A Christ-Centered Commentary. Volume 4: Psalms 101–150. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway.

Bandstra, Barry. 2008. Genesis 1–11: A Handbook on the Hebrew Text. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press.

Bar-Efrat, Shimon. 1997. Narrative Art in the Bible. Journal for the Study for the Old Testament Supplement Series 70. Edited by David J. A. Clines and Philip R. Davies. Sheffield, United Kingdom: Sheffield Academic Press.

Barker, David G. 1986. “The Waters of the Earth: An Exegetical Study of Psalm 104:1–9.” Grace Theological Journal 7, no. 1 (Spring): 57–80.

Barker, Kenneth L. 1995. “Praise.” In Cracking Old Testament Codes: A Guide to Interpreting the Literary Genres of the Old Testament. Edited by D. Brent Sandy, and Ronald L. Giese, Jr. 217–232. Nashville, Tennessee: B&H.

Barrick, William D. 2018.“Exegetical Analysis of Psalm 104:8 and Its Possible Implications for Interpreting the Geological Record.” In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism. Edited by John H. Whitmore: 95–102. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship.

Bielo, James S. 2018. Ark Encounter: The Making of a Creationist Theme Park. New York, New York: New York University Press.

Bühler, Karl. 2011. Theory of Language. The Representational Function of Language. Translated by Donald F. Goodwin and Achim Eschbach. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing.

Bullinger E. W. 1968. Figures of Speech Used in the Bible: Explained and Illustrated. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic.

Burgers, Christian, Britta C. Brugman, Kiki Y. Renardel de Lavalette, and Gerard J. Steen. 2016. “HIP: A Method for Linguistic Hyperbole Identification in Discourse.” Metaphor and Symbol 31, no. 3 (June 27):163–78.

Burlet. Dustin G. 2024. “Antiquity and Arithmetic: Hyperbole and a Rhetorical-Critical Reading of Noah’s Ark.” Canon and Culture 18, no. 2 (October): 131–71.

Burlet. Dustin G. 2022. Judgment and Salvation: A Rhetorical-Critical Reading of Noah’s Flood in Genesis. Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications.

Cano Mora, Laura. 2009. “All or Nothing: A Semantic Analysis of Hyperbole.” Revista de Lingüística y Lenguas Aplicadas 4, no. 1 (October): 25–35.

Casson, Lionel. 1995. Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cassuto, Umberto. 1964. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Part One: From Adam to Noah. Translated by Israel Abrahams. Jerusalem, Israel: Magnes Press.

Claridge, Claudia. 2011. Hyperbole in English: A Corpus-Based Study of Exaggeration. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Clines, David J. A. ed. 1993–2011. The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew. Vols. I–VIII. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press.

Cruise, Charles E. 2018.“A Methodology for Detecting and Mitigating Hyperbole in Matthew 5:38–42.” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 61, no. 1 (March): 83–103.

Cruise, Charles E. 2017. “Writing on the Edge: Paul’s Use of Hyperbole in Galatians.” PhD diss. Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, Deerfield, Illinois.

Cserhati, Matthew. 2020. “Do Snakes and Lizards Form Separate Apobaramins?” Journal of Creation 34, no. 1 (April): 96–101.

Cserhati, Matthew. 2023.“Molecular Baraminology of Marine and Freshwater Fish.” In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Creationism. Edited by John H. Whitmore: 181–205. Cedarville, Ohio: Cedarville University.

Elsen, Jan, Özlem Cizer, and Ruben Snellings. 2013. “Lessons from a Lost Technology: The Secrets of Roman Concrete.” American Mineralogist 98, no. 11–12 (January): 1917–1918.

Estes, Daniel J. 2019. Psalms 73–150: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture. New American Commentary 13. Nashville, Tennessee: B&H.

Evans, Robert O. 2014. “Hyperbole.” In The Princeton Handbook of Poetic Terms. Edited by Alex Preminger, O. B. Hardison Jr., and Frank J. Warnke. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Ferré, Gaëlle. 2014. “Multimodal Hyperbole.” Multimodal Communication 3, no. 1 (January): 25–50.

Finkel, Irving. 2014. The Ark Before Noah. New York, New York: Nan A. Talese.

Gesenius, Wilhelm. 1910. Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar. Edited by E. Kautzsch. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Goldingay, John. 2008. Psalms. Volume 3: 90–150. Baker Commentary on the Old Testament Wisdom and Psalms. Grand Rapids,, Michigan: Baker Academic.

Gomes, Jean Francesco A. L. 2020. “Review of The Lost World of the Flood: Mythology, Theology, and the Deluge Debate.” Calvin Theological Journal 55, no. 2: 365–367.

Grogan, Geoffrey W. 2008. Psalms. Two Horizons Old Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans.

Ham, Ken, and Bodie Hodge. 2016. A Flood of Evidence: 40 Reasons Why Noah and the Ark Still Matter. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Hamilton, Victor P. 1990. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1–17. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans.

Hardy, H. H. II, and Matthew McAffee. 2024. Going Deeper with Biblical Hebrew: An Intermediate Study of the Grammar and Syntax of the Old Testament. Brentwood, Tennessee: B&H Academic.

Hill, Carol. 2001. “A Time and a Place for Noah.” Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 53, no. 1 (March): 24–40. https://www.asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/2001/PSCF3-01Hill.html.

Kaminski, Carol M. 2014. Was Noah Good? Finding Favour in the Flood Narrative. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 563. New York, New York: Bloomsbury.

Keil, Carl F., and Franz Delitzsch. 1996. Commentary on the Old Testament in Ten Volumes: The Pentateuch. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson.

Keiser, Thomas A. 2019. “Divine Sovereignty vs. Human Responsibility: Nuancing Kaminski’s Was Noah Good?”. Westminster Theological Journal 81, no. 2 (Fall): 195–204.

Klein, William W. Craig L. Blomberg, and Robert L. Hubbard, Jr. 2017. Introduction to Biblical Interpretation. 3rd ed. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

Koehler, Ludwig, and Walter Baumgartner, eds. 1994–2000. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. 5 vols. Revised by Walter Baumgartner and Johann Jakob Stamm. Translated and edited by M. E. J. Richardson. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill.

Lapointe, Roger. 1970. “Divine Monologue as a Channel of Revelation.” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 32, no. 2 (April): 161–181.

Leupold, H. C. 1974. Exposition of Genesis. Vols. 1 and 2. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker.

Levinsohn, Stephen H. 2011. “רַק and אַךְ: Limiting and Countering.” Hebrew Studies 52: 83–105.

Lightner, Jean, Tom Hennigan, and Georgia Purdom. 2011. “Determining the Ark Kinds.” Answers Research Journal 4 (November 16), 195–201. https://answersresearchjournal.org/determining-the-ark-kinds/.

Long, V. Philips. 1994. The Art of Biblical History. Foundations of Contemporary Interpretation. Vol. 5. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

Longman, Tremper, III. 2016. Genesis. Story of God Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

Longman, Tremper, III. 2005. How to Read Genesis. Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP.

Longman, Tremper, III. 2024. The Old Testament as Literature: Foundations for Christian Interpretation. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic.

Longman, Tremper, III, and John H. Walton. 2018. The Lost World of the Flood: Mythology, Theology, and the Deluge Debate. Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP.

Marsh, Frank Lewis. 1941. Fundamental Biology. Lincoln, Nebraska: self-published.

Mathews, Kenneth A. 1996. Genesis 1–11:26. New American Commentary 1A. Nashville, Tennessee: B&H.

Mathews, Kenneth A. 2023. Genesis 1–11:26. Christian Standard Commentary. Brentwood, Tennessee: Holman Reference.

McCarthy, M., and R. Carter. 2004. “‘There’s Millions of Them’: Hyperbole in Everyday Conversation.” Journal of Pragmatics 36, no. 2 (February): 149–184.

McFadden, K. 2012. “Hyperbole.” In The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. Edited by Roland Greene. 4th ed. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Morton, Glenn R. 1997. “The Mediterranean Flood.” Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 49, no. 4 (December):238–251.