The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

Metaphysical development in Hebrew biblical texts is especially elucidated through a series of word studies with a shifting emphasis that each cross-pollinates the others. Life is “whole being with movement”. Holy is ontologically “separate”. Clean is ontologically “appropriate for cult”. Righteousness is “appropriate in covenant”. Uncleanness and sin remove the appropriateness for cult and covenant, thus removing Israelites and Tabernacle from being holy. Purification sacrifice recovers for holy and clean, and for humans also provides forgiveness. Note: To view Hebrew characters, please refer to the PDF version.

Keywords: Life, Soul, Death, Sheol, Holy, Common, Clean, Unclean, Righteousness, Unrighteousness, Sacrifice, Purification, Atonement, Forgiveness

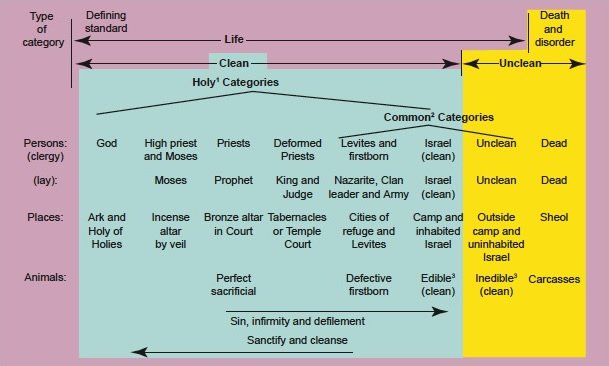

Metaphysical development in Hebrew biblical texts is especially elucidated through a series of word studies with a shifting emphasis that each cross-pollinates the others. Life is “whole being with movement”. Holy is ontologically “separate”. Clean is ontologically “appropriate for cult”. Righteousness is “appropriate in covenant”. Uncleanness and sin remove the appropriateness for cult and covenant, thus removing Israelites and Tabernacle from being holy. Purification sacrifice recovers for holy and clean, and for humans also provides forgiveness. The textual development to illustrate and warrant these concepts on the subsequent pages is summarized by the author together in a chart (fig. 1) that crystallizes the essence of each word in their relationship to others.

If a person is interested in understanding the Old Testament meaning of these terms, then these word studies are critical to appreciate the ancient Near Eastern nuance of each idea and to understand many biblical texts. Such an informed perspective is essential for a proper framing of an interpretation of passages that include these words (life, holy, clean, righteousness, and sacrifice). Likewise, in developing a broad theology or metaphysic of the Old Testament, these word studies are essential for its framing and content. These contents and framework of an Old Testament metaphysic is especially what this paper is setting out to show. The big picture showing overlapping relationships of these concepts is presented in Fig. 1 but also developed textually over the pages that follow.

Life and Death

The Hebrew concept of life is showcased in word studies of hyh and npš. The Hebrew concept of death is seen in word studies of mwt and š’ol. Life is the opposite of death but occasionally some are restored to life from the dead (1 Kings 17:22; 2 Kings 13:21). Furthermore, the boundary between these concepts overlaps as is especially evident when someone is ill or oppressed and laments in the psalms, indicating dying but not disposed of yet.

Contemporary concepts of life and death have a great deal of overlap with these biblical ones but they do not divide the lines in the same place. For example, a contemporary biological definition of life would be the congruence of several of the following attributes: motility, metabolism, growth, irritability, dynamic equilibrium, self-replication, and mutability. This concept of life includes plants, animals, humans, and microbial organisms. Whereas, the Hebrew concept of life excludes plants as nonliving structure at the climax of the form of Creation (Genesis 1:11–12; days 1–3 of Creation develop the form of the Creation parallel to Creation days 4–6 which develop the contents of Creation). Plants are never said to be alive in biblical Hebrew or in second Temple1 Jewish literature (Jewish documents from fifth century BC through second century AD). The microbial is not discussed with regard to life in the Bible or in second Temple Jewish literature, though both bodies of literature mention mildew and leaven as growing like plants in ways that the Hebrew does not describe as life (for example, Exodus 12; Leviticus 13:39; 25:5; Matthew 13:33).

Furthermore, contemporary concepts of death, such as the 1981 President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical Behavioral Research (1981) framed a focus on death with scientific precision as the irreversible cessation of: (1) circulatory and respiratory functions, and (2) all functions of the entire brain, including brain stem. Such a definition of death also excludes plants and the microbial. This definition would include the lack of biological functioning which the Hebrew concept of death also describes. However, the Hebrew concept of death based on this word study includes a continued cognitive functioning of life beyond the grave and a personification of death reaching into the troubles of this life to draw the vulnerable into the death experience. So the definitions and the lines are different from the biblical concepts of life and death and those of our contemporary context.

Fig. 1. Life, clean and holy, and Old Testament view. Notes:

1 Holy is any separate category set off from those to the right that do not measure up to its level of being.

2 Common is all those categories to the right that do not measure up to the separated holy category, within the range of common categories.

3 Land animals are greater than animals of sea and air within this category.

The primary word for life in Hebrew is hyh and its cognates. The word occurs 764 times in the Old Testament. About 70% of the instances refer to human life, 17% refer to animals and 11% refer to God as living, npš is a strong secondary word for life at least 43% of its uses (295 times) clearly indicating life. Both words are strongly connected to the experience of life rather than an abstract principle of life (Knibb 1998; Schmick 1980). Both words contribute to a meaning of wholistic living, moving, accomplishing and being blessed.

God is the living God,2 which is synonymous to identifying that God is a soul npš.3 Both words combine to communicate that God is vibrant, active and acts in the midst of human situations. God is the source of life originally (Genesis 1:29–30; 2:7). Special emphasis on the living (hyh) quality of God is developed within the former prophets of Samuel and Kings, and the latter prophets of Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Perhaps, the precarious situations (and the obvious need to trust God) highlight God as alive to meet the need and redeem Israel from whatever the risk. However, God is developed as alive from 19 Old Testament books, so that it is a broadly developed conception as well. God lives forever (Daniel 12:7, olam) which serves as a contextual model informing the only clear passage in the Old Testament where humans awake in personal resurrection to live forever (Daniel 12:2, olam). Additionally, Hosea 6:2 fostered a sentiment among Pharisaic second Temple Judaism that began to see this biblical text describe the general resurrection and even a Messianic resurrection on the third day.4 Jesus and Paul5 might be informed by such a view in predicting and recording as predicted that Jesus will resurrect on the third day (Matthew 12:40; 16:21; 17:9, 12, 22–23; 20:18–19, 27:63; Mark 8:31; 9:12, 31: Luke 9:22, 44; 17:25; 18:32; 24:7; John 2:19; 1 Chronicles 15:4). This concept of everlasting life develops further (discussed under š’ol below) as continued movement and blessing beyond the grave under Pharisaic and sectarian second Temple Judaism.6 Jesus in the gospel of John draws such everlasting life back into this life so that the two expressions of life (earthly and everlasting life) are coterminous for the believer now in Christ (John 3:16, 36; 11:25; and possibly 4:14 and 6:40).

Ezekiel develops that the four “living” creatures which look like animals in the immediate presence of God are “alive” (Ezekiel 1:5, 13–22; 3:13; 10:1–22; 11:22; similar imagery continues in Revelation 4:6–9; 5:6; 6:1, 6; 7:11; 14:3; 15:7; 19:4). By their description these “living” creatures are likely cherubim, the security and worship leaders for Yahweh’s heavenly throne room. Their movement may be quickly back and forth but in these texts it is always in close proximity to the divine presence.

There is no description of vegetation being alive; plants are treated as less than the level of life. Neither are plants said to die but they can be cut down or dry (for example, Isaiah 37:24; Jonah 4:7). The only instance that connects a plant with life is the tree of life which as an actual object is not described as alive but is involved by God to “bestow life contributing to wholeness” (Genesis 2:9; 3:22, 24). The second Temple Jewish apocalypse The Life of Adam and Eve conjectures that God placed the cherubim to protect humans from the tree of life (in Genesis 3:22–24 so that they would not be fixed in our corrupted condition without any hope of change.7 Contrary to this, the tree of life develops into a metaphor for extending vitality and benefit (Proverbs 3:18; 11:30; 13:12; 15:4), and eventually appears again in the final form of the Kingdom (Revelation 2:7; 22:2, 14). However, ultimately it is God who gives, sustains, or does not preserve life (Job 33:4; 36:6; Psalms 27:1; 36:9; 64:1; Jeremiah 2:13; 17:13).

The word for life (hyh) indicates movement and activity in a few instances where inanimate objects are described. For example, “living” (hyh) water is that which is flowing, even very gently so as to fulfill the criteria for ritually purifying washing or mikvot (Genesis 26:19; Leviticus 14:6, 52; 15:13; Numbers 19:17; Song of Solomon 4:15; Zechariah 14:8). Leviticus 14:6 connects the hyh “movement” of water with that of animals, a “living” bird is killed over “living” water and then another “living” bird is sprinkled with the dead bird’s blood and then released in an open field in the process of cleansing a leper (Leviticus 14:6–7, 50–53). Eventually, in Kingdom “living” water will flow from Jerusalem (Zechariah 14:8; Revelation 7:17; 21:6). This benefit of living water is something Jesus promises as internal for believers, resulting in everlasting life (John 4:10, 14).

Animals are alive and are often referred to as “lives”8 and “souls” or “persons” npš.9 Often these terms combine together to emphasize the vibrant moving characteristic of the animals and translated in the Septuagint with the parallel phrase “living souls” (ψυχων ζωσων; Genesis 1:21–24; 9:10, 12, 15). That is, animals do not have a soul or life, they are wholistically souls and lives.10 These living souls are described as fish, animals of the field, domesticated animals, rodents, and insects. For example, they are called “lives” (hyh) of the field as wild animals (Exodus 23:11, 29; Leviticus 17:13; 25:7; 26:6, 22; Job 5:22–23). The concept of animal life is broadly developed from 16 different books of the Old Testament.

Extending the animal imagery, 1 Samuel 2:15 identifies that uncooked raw meat, neither grilled nor boiled, is “living” or “whole” (hyh) even though it has just been killed and the fat portions have not been cut off it yet, to be offered in sacrifice to God. So “life” in this instance is an appropriate designation of an animal carcass before it is prepared for eating and sacrifice. Likewise, in the midst of human domination of animals (for obtaining food) there is a restriction (Genesis 9:4). Living flesh ’d btr bnpšw) and blood (dm), which emblems this condition of life, are both excluded from human diet. This restriction excludes from human diet meat that is still alive, such as swallowing goldfish and first kill celebrations where the animal begins to be devoured while still alive. Letting 1 Samuel 2:15 inform this Genesis 9:4 statement of life would likely identify whole sushi and similar raw uncooked meat as “alive” (npš) and thus inappropriate for one’s diet on the basis of the Noahic Covenant as well. The Septuagint of 1 Samuel 2:15 omits the last words of the verse likely because ζϖη doesn’t include dead uncooked meat within its semantic field. However, such a whole corpse view would be further supported by the instances that npš as a normal word for “life” instead refers to human corpses (Leviticus 19:28; 21:1, 11; 22:4; Numbers 5:2, 6; 6:6, 11; 9:6–10; 19:11, 13; Haggai 2:13).

Extending the imagery in a different direction, Genesis 6:17–19 identifies that all flesh (both human and animal) is alive. With Adam and Eve given the task of subduing to rule the world. Adam expresses hope by identifying that Eve is the “mother of all living” (Genesis 3:20). Likely, such a reference indicates Eve as a progenitor of the human race and the queen over all life.

Humans are alive (hyh, Genesis 2:7; 3:17; 7:11; 9:28; 11:11–26; Exodus 1:14). Human life is also indicated by 68% of the instances of npš11 (Brown Driver, and Briggs 1953, p. 659; Wolff 1974, pp. 24–25). These holistic uses include npš as “life” or “person” in 29% of the instances.12 Additionally, the word npš stands as a pronoun 25% of the times it is used.13 It is an unfortunate philosophical perversion that takes “soul” (npš) as an immaterial aspect of humanity because there is a strong emphasis on npš being holistic such that npš can even be put in irons (Psalm 105:18). As such, it is far better to take npš as a “living thing” rather than a quality possessed.

The concept of life is opposite of death (mwt)14 and often in near contexts with close development of death 13% of the instances of hyh.15 For instance, to “crush life” brings one close to death (Psalms 88:3; 143:3; Lamentations 3:53). Additionally, when npš is “cut off” or “required” by God then it means someone is killed (Genesis 9:5; 37:21; Exodus 12:15, 19; 21:23; Leviticus 7:20, 21; 24:17–18).

Eventually all humans will die and go to experience š’ol. However, the psalmist in difficult times encourages prayer for living forever in the sense that we do not wish to see š’ol prematurely (Psalms 49:9 and 89:48). That is, in the Old Testament context of suffering, life is fleeting and it wastes away (Job 7:7, 16). In such suffering, no one can ever be sure of life (Job 24:22).

Another 11% of the instances of hyh emphasize by their contexts that “life” is a continuing to live.16 By extension, one form of continuing a father’s life is through procreation (Genesis 19:32–34; 30:19).

Life (hyh) is an intrinsic and experiential good (Schmick 1980, 1:279). “All that a man has he will give for his life” (Job 2:4), and “a living dog is better than a dead lion” (Ecclesiastes 9:4). This is the land of the living (Isaiah 53:8; Jeremiah 11:19; Ezekiel 26:20; 32:24–32). Such living are in a position to praise the Lord, a condition functionally reserved in the Old Testament for those alive (Isaiah 38:19). With the development of resurrection teaching, second Temple Jewish and the New Testament include those in heaven with everlasting life as also participating in worship (Revelation 4:10–11; 5:8–13).17

By extension, life (hyh) is a blessing Schmick 1980, 1:280). Moses sets out the possibility of curse and blessing within the Mosaic Covenant, and then urges Israel to choose “life”, which God gives generously to those who obey Him (Deuteronomy 30:15–20; 32:47). Such a meaning includes more than movement but extends to a sense of wholeness (Brensinger 1997, 2:109). Psalm 119 celebrates the blessed life provided through the Law of which the pious Israelite keeps (Psalms 119:17, 77, 116, 144, 175). On a more horizontal framework, wisdom literature offers a way of life that reaps the blessing of life sown (Proverbs 2:19; 5:6; 6:23; 10:17; 15:24). Such a condition of life as blessing also entails “recovery from illness” or “being revived” (Joshua 5:8; 2 Kings 20:7; and not healed 8:10) (Brensinger 1997, 2:109). Similarly, hyh is used of “bringing the dead back to life” (1 Kings 17:22; 2 Kings 13:21). On a national scale Israel as a nation is brought back to life for a time of national restoration and kingdom (Isaiah 26:19; Ezekiel 37:1–14; Hosea 14:7). In a milder form hyh means “rejuvenate” and “sustain” with food and drink (Judges 15:19; 1 Kings 18:5). The concept of life (hyh) as preservation, reviving and continued blessing is prayed for in extenuating circumstances (Psalms 4:2; 22:26; 69:32; 71:20; 80:18; 85:6; 138:7; 143:11).

Among the prophets, obedience to the Mosaic Covenant fosters life and rebellion threatens such life. Within the Mosaic Covenant, sin negates righteousness and puts life at risk (Ezekiel 18:20; 33:12–13). Whereas, the righteous will live (Ezekiel 3:21; 18:9, 17, 19). Likewise, using a metaphor of a register of citizens, Isaiah identifies that those listed among the “living” (that is those faithfully trusting Yahweh and obedient to the Mosaic Covenant) will be called holy (Isaiah 4:3). Furthermore, the truly repentant from his sins will also live (Ezekiel 33:15–16). Therefore, all humans should repent of their sins to live (Ezekiel 18:32; 33:11; Amos 5:4–6).

Two late passages develop hyh with regard to a “restore to wholeness” meaning for inanimate objects (1 Chronicles 11:8 a city and Nehemiah 4:2 a wall). “Here, hyh again denotes a qualitative sense of wholeness; that which was broken is put back together” (Brensinger 1997, 2:112).

Various words are used to describe the concept of “death” but the concept is dominated by (mwt). “Death” (mwt) is opposed to life, not moving, not able to accomplish things and cursed. Life and death are ultimate opposites (Deuteronomy 30:19; 2 Samuel 15:21; Proverbs 18:21; Jeremiah 21:8). One hundred percent of the 920 times mwt is used in the Old Testament it means death as the loss of life of a person (npš) as evidenced by physical death. Usually this death is of a human but occasionally an animal is also described to die (Genesis 33:13; Exodus 9:7; 21:34–35; 1 Samuel 24:14; 2 Samuel 9:8; 16:9; Ecclesiastes 9:4; Isaiah 50:2). Occasionally, human death and animal death are described in the same passage in the same manner, as in the Flood (every living [hyh] thing [npš] with the spirit [ruh] of life [hyh] died [mwt], Genesis 7:21–23. Notice that humans and animals such as cattle, lizards, and insects have spirit (ruh) which leaves their body when they died (Ecclesiastes 3:19–20). Solomon grieves that human and animal death is the same in that: human and animal bodies return to dust, and the spirit or breath (ruh) leaves the body. Who knows which direction human or animal spirit goes, because one can’t see ruh though you can see the animating effect in a life (Ecclesiastes 3:19–20, similar to: we can’t see wind but we can see its effect).

Death is often described as violent: destroyed by wind storm (Job 1:19), by punishment (Genesis 9:6; Deuteronomy 19:12), by war (Isaiah 22:2; Jeremiah 11:22), and by starvation (Jeremiah 38:9).

Oftentimes, things are not themselves dead but cause death (mwt and š’ol in parallel), like wars, cords and snares (2 Samuel 22:5–6; Psalms 18:5; 116:3; Proverbs 13:14; 14:27; 21:6).

Death is also seen as a curse. One of the most devastating features of futility is that of death. It is both ironic and part of the ancient Near East chaos view that souls (npš) die (for example, Merrill 1997, 2:887; Oldenburg 1969, pp. 69–77). God warned Adam that in the day that he would eat from the forbidden fruit that he would surely die (mwt, Genesis 2:17). God’s oracle of judgment spoke of Adam eventually dying and returning to dust (Genesis 3:19).18 So perhaps the sure death is a condemnation of judgment that could be said to be a walking death which eventually results in full death. Likewise, God announced a curse to Abimelech in a dream by telling him that he is a dead man for marrying a married woman (Genesis 20:3). Abimelech was only able to recover himself by returning Sarah to Abraham. This is echoed in the Mosaic Covenant, Yahweh set out covenant curse as death for Israelites who do not obey the Mosaic Covenant (Deuteronomy 30:19).

The concept of death as curse sets up a Two-Ways framework. For example, the Rabbinics understand the Fall through a Two-Ways framework, as evident in Song of Songs Rabbah 1.9.2 claim, “God set before him two ways, the way of life and the way of death, and he chose the way of death and rejected the way of life.” The Mosaic Covenant sets before Israel the two ways of life and death, conditional upon their obedience to the Mosaic Covenant (Deuteronomy 30:15–16).19 As such, death (mwt) is the just condemnation for the wicked (Deuteronomy 19:6; 21:22; Jeremiah 21:8; 26:11, 16). Such a Two-Ways framework also is observable within wisdom literature’s description for how creation works with the natural consequence of death for those who follow the foolish way (Proverbs 8:36; 14:12; 16:25).

Death is thus a mysterious and fearful experience which at best is euphemistically called sleep (Psalm 13:3). Impending death provokes terror, panic, bitterness, and regret (1 Samuel 5:11; 15:32; Psalm 55:4; Ecclesiastes 3:19; 7:26). Death entails going down into a cave or pit that has multiple chambers (Psalm 22:15; Proverbs 5:5; 7:27). Such a death experience includes returning to dust, perhaps in the decaying process of creation constituents, perhaps in that this cavernous environment as dusty (Psalm 22:15; Ecclesiastes 3:20).

In the Old Testament, the afterlife is described as in š’ol. The concept of š’ol emerges from the Pentateuch as a grave or a cavernous pit to swallow Korah in judgment (Genesis 37:35; 42:38; 44;29, 31; Numbers 16:30, 33). In the Old Testament š’ol broadly becomes a synonym for death20 (cf. Galenieks 2005) and grave.21 By extension, the concept of š’ol becomes the lowest pit of the earth and a hidden area, though not hidden from God (cf. Galenieks 2005).22 In the more developed theology of David, Solomon and the later prophets, š’ol takes on qualities of a cognitive realm of the dead (Proverbs 7:27; 9:18; Isaiah 14:9, 11, 15). In this environment, all the dead are lying in š’ol on their grave shelves or beds though they can be aroused (Isaiah 14:9; Ezekiel 23:21–30). As such, the realm of the dead; weakens, shames and silences proud rebels (Psalm 31:17; Isaiah 5:14; 14:10; Ezekiel 31:15–17; 32:21).

Death (mwt) and š’ol are personified and encroach into the land of the living when a life is at risk. While mwt is not in the Old Testament as an expression of the god Môtu of Ugaritic texts (Oldenburg 1969, pp. 69–77), death is personified as a strong enemy for humankind (Song of Solomon 8:6). mwt is able to kill (Jeremiah 18:21, literally “be slain by death” (Merrill 1997, 2:887)). In rebellion, Israel made a covenant with personified death and š’ol but God will rescue them from judgment by a tested stone laid in Zion (Isaiah 28:15, 18). The personification of death extends to a family of diseases like leprosy which devour the skin and the body (Numbers 12:12; Job 18:13). Death (mwt) can climb through windows to pursue the living and can overwhelm its victims like waves (2 Samuel 22:5; Jeremiah 9:21). Likewise, this effect of š’ol reaches into this life at precarious times and draws its victims down into its dark domains (Leviticus 26:16; Job 17:14; Psalms 9:15; 23:4; 30:3; 31:9; 32:3–4; 42:4; 88:3; 102:3–7; 103:4; Isaiah 10:18; Jeremiah 19:9). As fever wastes the person (npš), he loses vigor and yearns intensely. The eye pictures this wasting away in crying about impending death (Psalms 6:7; 40:12). In such a condition, flesh and bones lack sound health (Psalms 32:3–4; 38:3–7; 102:3–7). The person (npš) is poured out in lament (Job 30:16; Psalm 42:4). The person (npš) draws near to š’ol as death approaches (Job 33:22; Psalm 30:3). In the Old Testament, death and š’ol can be thwarted but usually such salvation is accomplished by rescuing those at risk ahead of time so that their plight does not culminate (Joshua 5:8; 13:14; 2 Kings 1:2; 8: 8–14; 20:7; Ruth 4:15; Psalm 78:50; Isaiah 38:9, 21). Eventually God will ransom Israel from the power of death (mwt) and š’ol so that they will be a regathered people in Kingdom (Hosea 13:14).

The concept of resurrection in the Old Testament is marginal at best (Brueggeman 1997, pp. 483–484; Kennard 2008, pp. 333–335; von Rad 1962–1965, 1:470–471; 2:350; Wright 2003, pp. 85–128). For example, the Pentateuch occasionally states that the heroes of the faith are gathered to their forefathers. However, when there is no family tomb, such a reference is a very ambiguous comfort (for example, Numbers 20:24, 26). In a vague event, the witch of Endor conjured up Samuel bodily from the grave (1 Samuel 28:14–20). While he vanished when the conjuring was over, he must have been available from š’ol to temporarily bodily resurrect. Additionally, Ezekiel’s vision of the valley of dry bones is better seen as a metaphor describing Israel’s national resurrection and reunion, rather than a personal resurrection of individuals (Ezekiel 37) (Zimmerli 1983, pp. 256–257). Perhaps the only clear mention of personal resurrection in the Old Testament is that of Daniel 12:2–3 where the dead will awake from their sleep among the dust to either everlasting life or everlasting contempt (Baldwin 1978, pp. 204–206; Wright 2003, pp. 108–110).

This sort of resurrection hope is much more common in second Temple Judaism within the wake of developing Pharisaic theology.23 That is, the faithful in the Mosaic Covenant when they die continue to be blessed in the afterlife with bodily resurrection unto Paradise. In fact, Psalms of Solomon 14.3 utilizes Leviticus 18:5 to show that the Law dependent life continues into everlasting life; “the righteous ones of the Lord will live by it [the Law] forever” and again, “Love is keeping her commandments, Observance of her laws is the guarantee of immortality.”24 Furthermore, with reference to tortured and martyred Jews, 2 Maccabees identifies the Mosaic Covenant as God’s covenant of or toward everlasting life.25 This identifies that for 2 Maccabees unlike Psalms of Solomon, resurrection begins with everlasting life (Arenhoevel 1967, p. 159, no. 13) and is a life not yet attained (cf. Dunn 1998, pp. 152–153). Testament of Asher 5.2 joins 2 Maccabees in identifying that “everlasting life waits for death”.26 Within this framework, some Qumran manuscripts also speak of an afterlife as everlasting life,27 and possibly others even intimate bodily resurrection for the faithful.28

Second Temple texts extend the Deuteronomic blessing/curse of this life to a post-mortem judgment and afterlife, where the righteous are blessed in the afterlife with Deuteronomic blessing including salvation of everlasting life.29 While this afterlife is an extension of salvation beyond the grave that the Torah and Covenant Renewal Psalms never developed, such a resurrection idea was seen by second Temple Jews as having basis in biblical and extra-biblical psalms.30 Angels accompany God to gather the elect into Kingdom and gather the unrighteous for damnation.31 The sound of a trumpet or šophar horn will signal their gathering (Joel 2:1; Zephaniah 1:16; Zechariah 9:14; 1 Chronicles 15:52; 1 Thessalonians 4:16)32 much like it has called Jews to gather for Sabbath or other sacred occasions (Numbers 10:10; Joshua 6:5; 1 Kings 1:34; Psalm 81:3; Isaiah 27:13; Jeremiah 4:5).33 This gathering is presented in similar language as the Jews being gathered from dispersion (Isaiah 27:12–13).34 This visual and audible coming indicates that redemption is near. Thus Jewish parables commonly emphasize wisdom for being alert unto Kingdom.35 The righteous are then gathered into a Messianic banquet as a metaphor for Kingdom (Isaiah 25:6–9; Luke 14:15; 22:16–18; Revelation 19:9).36 Kingdom is described as the best of all eras. For example, in Kingdom, animals will be at peace with humans and the animals prey in a condition that returns to a peaceful pre-Fall Eden environment (Isaiah 11:6–9).

Holy and Common

Holy (qdš) is an ontological metaphysical category that means separate (Gammie 1989, pp. 9–11; Kornfield 2003, 12:522; Naudé 1997, 3:877; Neusner and Chilton 1993, pp. 205–230, especially 205, 208, 211; McComiskey 1980, 2:786; Wilson 1994).37 The system of the holy develops categories always applicable to the cult (Neusner 1980, p. 17). In Akkadian, qadāšu and qadištu are synonyms to clean or pure, while qadsutu means holy as set apart to god (Kornfield 2003, 12:524–525; Naudé 1997, 3:878; McComiskey 1980, 2:787). In Ugaritic, qdš means holy ontologically within the categories pertaining to god, such as shrine, priest, and cult prostitute (Naudé 1997, 3:878; McComiskey 1980, 2:787; Kornfield 2003, 12:524–525). Even the biblical concept retains qdš as including Canaanite temple prostitutes as holy or set apart for their pagan worship (Genesis 38:21–22; Deuteronomy 23:17). So qdš is not about morality but an ontological category of being identified in relationship to God as separate or sacred.

The antonym to holy is common (hl), Leviticus 10:10, 1 Samuel 21:4–5; Ezekiel 22:26; 44:23) (Dommershausen 1980, 4:410–417; O’Kennedy 1997, 2:146–147; Wiseman 1980, 1:289–290). At times common can be identified with unclean as a synonym (Leviticus 10:10; Ezekiel 22:26; 44:23). However, ?? ??? / hl? does not mean unclean because at times only clean objects are contemplated and the holy clean object is designated as distinct from the common clean object. The term common (hl) usually occurs in comparisons designating what is not as set apart as that which is holy (qdš). For example, in Ezekiel’s Temple a five foot wall is to be built around the Temple court marking off that holy area around the Temple from the common area further out (Ezekiel 42:20). Likewise, within the clean land a special area is ultimately set apart for the priests to dwell in as holy for their dwellings and a smaller portion is for common use near their dwellings (Ezekiel 48:11–12, 14–15). These are all the instances where hl is used in the biblical text, which illustrates that qdš does not really mean separate from a lesser level (as Rudolf Ott’s numinous developed [Otto 1950] probably more reflective of a Kantian noumena metaphysical idea and followed by Mircea Eilade’s sociological dualism informed by broad international religious practice) (Eliade 1961); qdš means separate to its ontological level of being. These levels of being are separated to God as part of the chain of being in their appropriate closeness to God.

Holy (qdš) means separate as in a level of being. The supreme example of holiness of being is that Yahweh is Himself holy and thus defines the standard of what holiness means, separate to His category of Being (Leviticus 11:44; 19:2; Numbers 20:12–13; 27:14; Isaiah 5:16; 6:3; 57:15). qdš is even used as a synonym for the divine name (Isaiah 40:25). As “Holy One of Israel”, God demonstrates Himself in judgment (Isaiah 1:4; 5:16, 24; 30:11; 31:1; 37:23; 47:4) and salvation (Isaiah 10:20; 12:6; 17:7; 29:19; 30:15; 40:25; 41:14, 16, 20; 43:3, 14–15; 45:11; 48:17; 49:7; 54:5; 57:15; 60:9, 14). All that is Yahweh is holy: He has a holy arm (Psalm 98:1; Isaiah 52:10), a holy word (Psalm 105:42), and a holy Spirit (Psalm 51:11; Isaiah 63:10). All that holy Yahweh touches is holy: the holy city (Isaiah 52:1), the holy mountain (Exodus 19:33; Isaiah 57:13), holy day (Isaiah 58:13), holy people Israel (Isaiah 11:9; 62:12; Ezekiel 28:22, 25), holy house (Isaiah 63:15; 64:11)38 with holy courts (Isaiah 62:9; Ezekiel 42:20).

A very significant passage to define Yahweh as holy is Isaiah chapter six. Here Yahweh’s holiness is in close connection to His Kingship. In contrast to the temporality and frailties of human rulers dying, Yahweh transcends far above them in His reign on the heavenly throne (Isaiah 6:1–2). The vision is so lofty that Isaiah does not describe Yahweh Himself but rather focuses on His regal glory with His holiness. Such regal glory is the majesty and splendor attendant upon the manifestation of God. The seraphim39 (literally “glowing ones”) accentuate Yahweh’s separateness by calling out in a tripling of “holy” which should be understood as a Hebraic metaphor for the supremacy of holiness; “Holy, holy, holy is Yahweh of hosts” (Isaiah 6:2–6).40 This later term for Yahweh, “sebaoth” indicates that He is the “General of His armies”. In such a reign and executor of His warfare, He is supremely holy. Furthermore, the seraphim picture Yahweh’s holiness, by covering their feet and faces with their wings. After seeing the vision, Isaiah’s first utterance emphatically declares Yahweh to be the King (Isaiah 6:5) as he recoils in terror confessing his uncleanness and sin. Such fear and reverence is the proper response when confronted with the holiness of Yahweh (Isaiah 6:2–3, 5; 8:13). Yet it shows that while holiness is not essentially purity or morality, it can raise ritually appropriate issues like uncleanness, and the related issue of Isaiah’s sin. This paper develops these issues embedded in Isaiah’s confession under the relationship between: holy, clean and righteousness. Isaiah is ultimately aware of his own sin and the sin o Israel, and the gulf of their uncleanness which these cause between them and Yahweh. Yahweh’s holiness extends to Isaiah graciously a glowing coal carried by a glowing one (seraph) for the purpose of cleansing and forgiveness much like the Akkadian lip purification ritual accomplished (Hurowitz 1989, pp. 39–89, especially the sources mentioned in note 26 on p. 49). With such cleansing and forgiveness obtained through an alternative to sacrifice, Isaiah no longer has terror before Yahweh. What is left is the fear of Yahweh that results in obedience without a fear of others (Isaiah 6:7–8; 8:12–13; 29:23). When Yahweh called for His messenger, Isaiah quickly responded. The message he was to declare as the messenger of the King was to harden Israel’s heart, drawing the contrast further between Yahweh and His people. The end result of this activity would speed Yahweh’s judging holiness to destroy rebellious Israel.

When Holy Yahweh established a relationship with Israel, then the relationship and Yahweh’s personal holy presence demands Israel to be holy as well; “You shall be holy for I Yahweh your God am holy” (Leviticus 19:2; 11:44–45). Yahweh’s holiness separates Israel to be metaphysically separate: “Thus you are to be holy to Me, for I Yahweh am holy; and have set you apart from the peoples to be Mine” (Leviticus 20:26). To enter into Yahweh’s presence and to continue in Yahweh’s presence as a relationship involving His benefits requires Israel to be holy (Exodus 19:10, 14; Numbers 11:18; Joshua 3:5; 1 Samuel 16:5; Joel 2:16). While holiness essentially is occupying a metaphysical separate level it shows itself by doing separate deeds, because each metaphysical level is separate for a purpose which reflects its level. To Israel, Yahweh commands, “You shall consecrate yourselves therefore and be holy for I am Yahweh your God and you shall keep My statutes and practice them; I am Yahweh Who sanctifies you” (Leviticus 20:7–8). Obedience to a morality does not render Israel holy but because they are separated by God to a relationship with Him, the implication for Israel is that they should obey His standards. The context develops which specifics identify Israel as set apart to Yahweh, such as faith (Deuteronomy 32:51), or not profaning Yahweh’s name (Leviticus 22:32), or being ready to be involved in Yahweh’s sacrifices (1 Samuel 16:5). Israel’s obedience in Mosaic Covenant is with regard to holiness and the whole of the Mosaic Covenant command system (such as the Decalogue) is dependent upon and contained within holiness (Leviticus 19:2–37) (Milgrom 2001, pp. 1602–1603).41 Furthermore, each respective group in relationship with Yahweh reflects appropriate standards which Yahweh tailors for them. For example, the Levites set themselves apart for their duties (1 Chronicles 15:12; 2 Chronicles 30:17; 31:18).

Holiness does not mean moral purity. For example, the garments that Aaron wore set him apart as the high priest, and yet garments have no intrinsic moral value; thus amoral holiness (Exodus 28:3). Yahweh is the One Who set Israel apart by His choice; not their works or lifestyle; holiness beneath morality (Exodus 31:13). An Israelite’s separation could be defiled by a man dying close to him evidencing no immorality on his part, though he must start his separation again; amoral reduction of holiness to common (Numbers 6:11). The concept of morality is easily read into a passage like 2 Samuel 11:4, but it should be understood to say Bathsheba had to wait for a time to be legally pure from the “uncleanness” of the sex act. The issue was not her recovery from the sin of adultery, for which the punishment was death. In this context, the word had not yet come concerning David’s forgiveness. Therefore, Bathsheba is immoral and becoming holy through the cleansing process. Additionally, idolatry is immoral yet the people are set apart for a sacred assembly for Baal; immoral holiness (2 Kings 10:20). As an adjective, qdš refers to temple prostitutes separated to their pagan shrines for licentious Canaanite worship; immoral holiness (Genesis 38:21–22; Deuteronomy 23:17) (Kornfield 2003, 12:524–525; Naudé 1997, 3:878; McComiskey 1980, 2:787). Furthermore, the enemies of Judah were set apart by God for destruction and captivity; holy common immoral nations (Jeremiah 6:4; 22:7; 51:27–28). Objects and times in themselves have no moral state which further helps to clarify that holy (qdš) does not mean morality. For example, Exodus 28:38 says that the holy things separated by Israel have iniquity transferred to them by the sin of Israel but that a small gold plate on the priest’s turban takes the iniquity away (Exodus 28:36). Thus the idea of holy (qdš) does not include moral purity because these amoral objects cannot be in iniquity and morally pure at the same time and in the same manner.

Likewise, time can be set apart as holy; amoral holiness. In the creation God set the Sabbath apart as holy in that He stopped His creative work for that day (Genesis 2:3; Exodus 20:11; 31:17) and then called Israel to likewise consider and treat the Sabbath as holy by stopping from work (Exodus 20:8–11; 31:13–17). Childs, connects Sabbath with the Tabernacle in the book of Exodus;

The first account of the tabernacle closes with the Sabbath command (31:12ff.); the second account of its building begins with the Sabbath command (35:1ff.). . . The connection between the Sabbath and the tabernacle is therefore an important one (Childs 1974, p. 541; Gammie 1989, p. 20).

This relationship is reflected within the holiness code, “You shall keep My Sabbaths and revere My sanctuary; I am Yahweh” (Leviticus 19:30).

Often holiness is described as being set apart for a purpose. For example, Jeremiah was chosen to be separate as a prophet of Yahweh (Jeremiah 1:5). Eleazar was chosen to be separate to keep the Ark (1 Samuel 7:1). The priests and Levites are chosen to be separate and then their duties are described (Exodus 19:22; 28:41; Leviticus 6:18, 27; 8:30; 21:8, 15, 23; Numbers 6:11; 1 Chronicles 18:14; 2 Chronicles 5:11; 26:1; 29:5, 34: 30:15, 24; 35:6; 44:19). Likewise food was set apart for the purpose of the priests and Levites to eat (Nehemiah 12:47). Leviticus 27:14–19, 22 identify vows setting apart a field or a house in corban for a purpose. This instruction on vows rendering things holy includes a clause by which the giver may redeem them for one-fifth of the market price. In such a situation the amoral becomes holy and then common without reference to morality or cleanness, so that purposefully holy is separate from each of these. Furthermore, Deuteronomy 22:9 urges the farmer to only sow one kind of seed in a field lest he must separate the produce of the field; the issue is practicality rather than morality.

These separate categories of holiness have gradation to them. This gradation is evident as Moses functioning as high priest consecrates the priests (Exodus 29; Leviticus 8) and as pattern for the prophets and judges to follow (Deuteronomy 18:15–18). Additionally, the gradation is evident by the High Priest having stricter obligation regarding cleanness than other priests (Leviticus 21:1–15). Also deformed priests still have rights to eat food for priests as holy which others can’t have, though in their deformed condition they are prevented from priestly service as common (Leviticus 21:16–24). Likewise, the first born are separate as God’s possession (Exodus 13:2; Leviticus 27:26; Numbers 3:13; 8:17; Deuteronomy 15:19) but the Levites substitute for the first born as a separate group for tabernacle service (Numbers 8:14–19). The priests and Levites have a greater access to the tabernacle and a great danger so they must receive danger pay (a tithe) for taking greater risk to keep Israel from being judged (Numbers 17:12–18:32). The people tithe to priests and Levites; Levites tithe to priests but priests do not tithe to anyone higher, indicating categories of separateness.

Philip Jenson proposed a grading of holiness to reflect a gradation from: very holy to very unclean (Jenson 1992, pp. 36–37). For example, his category of very holy includes: the holy of holies, high priest, sacrificial animals offered and not eaten and the Day of Atonement. However clear his system happens to be, His categories don’t quite fit the biblical textual description. For example, this category of the very holy is broader than he describes it and the use of very holy describes a comparison with others things in the context, much like the word for holy (qdš) alone functions. The Holy of Holies is definitely very holy (Exodus 26:33–34; 1 Kings 6:16; 7:50; 8:6; 1 Chronicles 6:49 [39]; 2 Chronicles 3:8, 10) but so are the incense altar, all tabernacle furniture, place for priests to eat sacrifice portions, everything designated Corban, and the Kingdom Temple site and Levite’s promised land (Exodus 30:10; 40:10; Leviticus 24:9; 27:28; Numbers 4:19; Ezekiel 43:12; 45:3; 48:12). The very holy includes Moses, Aaron and his sons and Aaron’s garments (Exodus 30:29; 1 Chronicles 23:13). The category of very holy includes all priestly daily activity: including specifically the daily offerings (burnt, guilt, grain, incense) some of which are eaten by the priests but not by the people (Exodus 29:37; 30:36; Leviticus 6:17 [10], 29 [22]; 25 [18]; 7:1, 6; 10:12, 17; 14:13; Numbers 4:4; 18:9; Nehemiah 7:65). So Jenson’s categories are too conceptually rigid and don’t reflect the use of the Hebrew words. Additionally, the previous paragraph developed additional levels of holy (such as deformed priests) which Jenson’s scheme does not take into account. Furthermore, Jenson conceived of holy and clean as merely separate levels of the same thing, which the word studies here show otherwise.

A superior gradation scheme was presented before him by Gordon Wenham that reflects that holiness and clean are related but not exactly the same kind of gradations (Milgrom 1991a, p. 732; Wenham 1979, p. 177; 1982, p. 123).42 This discussion in the present chapter follows Wenham’s categorization of the gradations in holy and clean as we attempt to reflect more accurately the Hebrew and the biblical text. On the chart on page one the concept of holy (qdš) is a category of comparison which marks any separate column to the left apart from any of the columns to the right. As such, some columns are listed as both holy and as common. For example, Levites are common compared to priests but holy compared to Israel. On the chart, the columns described as common have biblical texts using hl to indicate them. Likewise, each column described as holy is also indicated biblically by qdš.

Separateness (qdš) of gradation also has to do in categories we are in the West do not normally consider religious but they are identified as holy in the ancient Near East. For example, David and his warriors are separate for military purposes (1 Samuel 21:5; Isaiah 13:3; Jeremiah 6:4; 22:7; 51:27–28; Joel 3:9; Micah 3:5). This reminds us that in the ancient Near East war is a holy activity engaged in for God.

While holiness is a category of being, holiness is also something dynamic (Milgrom 2001, pp. 1397, 1602–1604). In such a dynamic condition, holiness is something that Israel must attain (Leviticus 19:2; 21:8 Septuagint 22:32), and priests must sustain (Leviticus 21:15; 22:16). Israel is to obtain holiness after the pattern that Yahweh is holy, so Israel is to live a distinctive life reflecting Yahweh’s commands (Leviticus 19:2; 21:8 Septuagint 22:32).43 Likewise, Sipra Emor 1.13 interprets Leviticus 21:8 as Israel is responsible for keeping the priests holy in regard to a forbidden marriage (Milgrom 2001, pp. 1808–1809). Furthermore, God continues to retain the priests in their respective holiness if they refrain from diminishing their holiness by acts of desecration (Leviticus 19:2–4, 9–18, 34; 20:8; 22:18, 32) (Milgrom 2001, pp. 1820–1821).

The extremes of holiness can be said to be contagious in the reverse of defilement from that which is unclean (Exodus 30:29; Leviticus 6:11). Menahem Haran describes persons and objects as included within this contagious holiness.

Any person or object coming into contact with the altar (Exodus 29:37) or any of the articles of the tabernacle furniture (30:29) becomes “holy”, that is, contracts holiness and, like the tabernacle appurtenances themselves, becomes consecrated. . . But contagious holiness . . . cannot be removed from a person or object. . . Complete avoidance of all contact with this holiness is an absolute necessity, for anyone who contacts it is liable to meet immediate death at the hands of heaven. Indeed, the Kohathites are explicitly warned not to touch the furniture lest they die (Numbers 4:15). An object that has contracted holiness must be treated in exactly the same way as the tabernacle furniture and all steps should be taken to prevent it affecting other objects. The censors belonging to Korah and his company which had come into contact with the altar became holy like the altar itself and henceforth their holiness could not be removed (Haran 1978, p. 176).

However, Jacob Milgrom more accurately acknowledges this contagious holiness only with regard to things, it does not induce persons into a higher category of holiness (Milgrom 2001, pp. 1820–1821). As such, an Israelite is not rendered especially holy by eating food for priests, instead such a sin puts the nation at risk under judgment from God (Leviticus 22:14–16). Additionally, Joab and Adonijah were not rendered more holy by grabbing a horn of the altar but rather they were even killed by sword as a judgment from Yahweh and Solomon for their continuing treasonous activity (1 Kings 1:50–52; 2:23–25, 28–33). However, the tabernacle furniture has been anointed with holy oil (Exodus 29:36; 30: 22–29; 40:9–11; Leviticus 8:10–11; Numbers 7:1, 10) and Aaron and his sons were likewise anointed (Exodus 28:41; 30:30; 40:13–15; Leviticus 7:36). Thus activity around the especially holy could be only performed by priests who were likewise holy. For example, when Korah’s censers were beaten into sheets for plating the outer altar it was Eleazar, son of Aaron who did this with other priests but not the Levites nor common Israelites (Numbers 17:2–5). Likewise, the priests had to cover and prepare the tabernacle furniture and then the Kohathites were allowed to carry them but not look at them (Numbers 4:5–20).

Second Temple Judaism saw God’s commitment to Israel as a real presence in the holy land and thus grounded their everlasting existence in the land on this divine commitment to His holy people.44 Recognition and alignment with the appropriate degree of holiness is how the Jew should respond under God’s rule.45 Yahweh both grounds Israel’s holy condition in the everlasting Kingdom and cultivates their morality for He will lead His holy people in righteousness.46

Clean and Unclean

Clean (thr) is a measure of what is cultic appropriate in light of one’s relationship with Yahweh, in contrast to unclean (tm’) which is inappropriate for the cult (Leviticus 10:10; 11:47; 14:57; 20:25; Numbers 5:28; Deuteronomy 12:15, 22; 15:22; Job 14:45; Ecclesiastes 9:2; Ezekiel 22:26; 44:23). Clean (thr) occurs 212 times in the Old Testament with a concentration in Leviticus and Numbers (93 times for 44%), Exodus 33 times for 16%), and Ezekiel (31 times for 14%) (Neusner 1973, p. 26).47 Unclean (tm’) occurs 283 times in the Old Testament with a concentration in Leviticus and Numbers (182 times for 65%), and Ezekiel (44 times for 16%). Jacob Neusner develops that they have to do with an ontological ritual purity (Neusner 1973, p. 1).48 As such, clean is that part of the Hebraic worldview that has to do with one’s relationship to metaphysical purity for cultic purposes. However, in later prophets this ontological condition shows that it is significantly affected by morality in Covenant as well. That is, sometimes unclean is sin and oftentimes it is not but uncleanness always keeps something or someone from being connected in a cultic relationship with Yahweh. Furthermore, while rebellious sin causes such uncleanness, not all uncleanness is caused by sin. So captivities and dispersions are caused by rebellion drawing Israel into unrecoverable uncleanness.

Throughout the ancient Near East there are cognates and synonyms that identify observable and regionally clean or cultic appropriateness (Averbeck 1997, 2:339; Yamauchi 1980, 1:343; Ringgren 1986, 5:288–290). While the Egyptian idea may be rooted in washing for ceremonial purposes; the Mesopotamian, Ugarit, and Hittite idea is more related to unmixed purity and brilliance. In observational use, the Hebrew thr describes a pavement made of sapphire as “clear and gleanin” as the sky (Exodus 24:10). Likewise thr describes the gold as “pure” for building the tabernacle, tabernacle furniture, and Temple (Exodus 25:11–39; 28:14–36; 30:3, 35; 31:8; 37:2–24; 39: 15–37; Leviticus 24:4–7; 1 Chronicles 28:17; 2 Chronicles 3:4; 9:17; Job 28:19).49 This use of thr indicates that the word conveys a metaphysically real quality of cultic appropriateness. Likewise, the incense burned there must be pure (thr, Exodus 30:35; 37:29). In fact, Malachi 3:3 uses the piel of thr twice for purifying precious metals and then metaphorically for purifying the Levites, so that they might function appropriately in the cult.

Jacob Neusner develops that clean (thr) and unclean (tm’) are neither hygienic nor with regard to dirtiness.

Purity and impurity—THR and TM’—are not hygienic categories and do not refer to observable cleanness or dirtiness. The words refer to a status in respect to contact with a source of impurity and the completion of acts of purification from that impurity. If you touch a reptile, you may not be dirty, but you are unclean. If you undergo a ritual immersion, you may not be free of dirt, but you are clean. A corpse can make you unclean, though it may not make you dirty. A rite of purification involving sprinkling of water mixed with ashes of a red heifer probably will not remove a great deal of dirt, but it will remove impurity (Neusner 1973, p. 1).

Some animals are appropriate for sacrifice and thus they are identified as “clean” (thr, Genesis 8:20; 7:2, 8). The remains of the sacrifice ashes should be disposed of in a ritually clean place outside of the camp (Leviticus 4:12; 6:11; 10:14). Yahweh provided instruction for Aaron and the priests to be thoroughly versed in what is holy and common, and what is clean and unclean so that they might not die as they approach Yahweh in the tabernacle (Leviticus 10:6, 9–11). The priests are to extend this instruction on to the rest of Israel so that the people would have full obedience to the Law. In the ancient Near East meat was not normally part of their diet but as part of a sacrifice, ritually clean (thr) meat cut from a sacrifice that had not touched unclean (tm’) objects are available for clean (thr) Israelites to eat (Leviticus 5:2; 7:19, 21).

Moses and Aaron were to instruct Israel concerning which animals were appropriate for them to eat, presumably during festivals (Leviticus 11 proximity to sacrifices, Leviticus 1–10 and specific instruction given to Aaron as proxy-priest Leviticus 10:8; 11:1; 13:1; 15:1), since a later discussion in Deuteronomy 12:15–22 for secular slaughter of meat permits unclean humans to partake of clean meat in contexts removed from the tabernacle. However, during the festivals Israel’s meat is likely not all offered in sacrifice since the list includes fish, which is never included as sacrifice. In Leviticus 11 and more briefly in Deuteronomy 14 the emphasis shifts from that which is clean (thr as in sacrifice) to that which is unclean (tm’), so that Israel does not defile themselves but remain consecrated (thr) for purposes of the festival in their appropriate category of holiness (Leviticus 11:44–47; 20:25–26). Since Israel surrounding the Tabernacle during the exodus is akin to when they will be on pilgrimage and campaign, the purpose of this discussion is to preserve Israel as holy and clean so that they may participate within the festival and battle camp.50

Leviticus describes all animals within four categories (while Deuteronomy strikes the last category) that encompass all animal kind: beasts, water creatures, birds, and crawling things (like rodents, lizards, and insects). Among the clean beasts are ruminants with cloven hooves. The clean water creatures have fins and scales. The winged creatures simply list 20 or 21 forbidden unclean birds. Deuteronomy forbids flying insects but Leviticus permits hopping insects like locust but forbids all swarming creatures. The fact that specific animals are chosen to be included and others excluded indicates thr functions on a metaphysical level of being (Neusner 1994, pp. 56–59; Neusner and Chilton 1993, pp. 205–230). Neusner summarizes the ontological status of uncleanness.

What this means is that uncleanness comes about through natural processes; its sources are unaffected by human will and not subject to culpability; uncleanness is not the result of voluntary action, therefore considerations of responsibility and blame do not enter, and moral judgments are not to be drawn because they are irrelevant. Uncleanness is an ontological taxon, not a moral one; it indicates what one may or may not do, where one may or may not go (Neusner 1994, p. 54).

That is, uncleanness prevents appropriate participation at the Temple and in the festivals, which cleanness permits.

A variety of theories try to make sense of the kosher lists: (1) the hygienic view that at least goes back to Maimonides in banning things that hold risks of parasites if inappropriately cooked but there is no hint of this explanation in the context (Albright 1968, pp. 175–181).51 However, many appropriate animals if not prepared correctly could affect a person so the list of exclusions is not driven by that motivation. Additionally, there is no hygienic reason for including within the kosher list God’s permission for resident aliens eating road kill banned from Jewish diet (Deuteronomy 14:21). Furthermore, illness is not treated pragmatically in Judaism, but rather such disease is seen as either inevitable or as a result of disobedience (Leviticus 26:25; Numbers 11:33; 12:10). (2) Cult-polemic theories (which go back to Origen) propose to forbid those animals sacrificed in pagan rituals which might represent deities.52 However, most of the animals sacrificed in Israel were offered in Canaanite and Egyptian rituals as well, some of which are similar to pagan deities. Furthermore, this view can’t explain the exclusion of camel, donkey, rabbit, and horse (Milgrom 1991a, p. 718). (3) In contrast, E. B. Firmage, and W. J. Houston, and M. Harris float the reverse, identifying the clean with similarity to context sacrifices or food eaten or local ecology (Firmage 1990, pp. 177–208; Harris 1977, 1985; Houston 1993, pp. 124–180).53 However, in the context the pig and dog were both eaten by a few and sacrificed to underworld deities, so both views (2) and (3) fail to account for these pagan inclusions, though of these two views view (3) is closer to the biblical list (Houston 2003, pp. 328, 330; Milgrom 1991a, pp. 650–652). Furthermore, ecological constraints have been shown to not produce cultural forms (Keesing and Strathern 1998, pp. 125–127). (4) Moral theories go back to Philo who proposed to imitate contemplation (illustrated by cud chewing ruminants), eschew violence of predatory animals, and restrain luxury (illustrated by the pig excluded as repulsive among most of the ancient New Eastern context).54 Whatever value such moral theories propose they do not explain much of the list. (5) A related view (proposed by the Epistle of Barnabus and resurrected by Jacob Milgrom) attempts to respect life by the severe limitation on the species permitted but he has not adequately replied to the criticism that there is no restriction on the quantity of meat eaten, as well as not giving specific guidance on why these animals were permitted.55 (6) M. Douglas modified this view to teach justice by protecting the weak swarming things, but there is no sufficient rationale for why the weak birds are permitted and the hopping insects too (Douglas 1993, pp. 3–23; 1999, pp. 152–175). (7) She also leads the proposal for these patterns reflecting deep mental structuralism56 but the view did not provide a consistent explanation for the anomalies so she has modified the view to reflect (8) covenant versus creation but this model breaks down because the “swarmers” are to be avoided even though they are the best evidence for the principle of fertility (Douglas 1999, p. 134–175). (9) These last several character options are similar to another, that of completeness: fish with fins, birds with wings.57 However, this view is arbitrary with no rationale for why these descriptions constitute completeness, and again the pig and many of the birds are complete on such a description but are still viewed as unclean. (10) The Leviticus Rabbah 12.5.9 proposed that the animals were an apocalyptic polemic against nations around Israel (Neusner 1991, pp. 81–84),58 and Clement of Alexandria argues that it is a polemic against unclean Judaism in favor of the church.59 However, these views completely ignore two facts: (a) many of these nations and Christianity did not exist in the time of the biblical revelation of these lists and (b) the resilience of kosher practice informing Jewish lifestyle shows that the primary Jewish interpretation applied the passage to diet not international or spiritual polemic (Daniel 1:8–16; Acts 10:10–16; 11:2–3).60 Since all these models are at odds with either themselves, or the biblical evidence, or the facts from the ancient Near Eastern culture, (11) I am left with the rationale for the clean animals being God’s fiat for the purpose of preserving Israel as holy and clean (Leviticus 11:44–47). That is, Israel must be preserved as separate and appropriate for the functioning of their cultic relationship with Yahweh. This rationale was proposed early by Rabbinic theology and continues by Jacob Milgrom (Milgrom 1991a, pp. 686–688).61 While I acknowledge that the closest pattern is the majority ancient Near Eastern diet (view 3b), there are unique features here with no explained reason, so the Israelite should just trust God by faith and obey the list He declares. Furthermore, sacrificial clean meat can even become unclean by delaying in eating it (Leviticus 7:18; 19:7 and probably Ezekiel 4:14; is this a factor of view 1 or just view 11 again?). If an Israelite is in doubt about whether an animal is clean or unclean, the priest is to decide its status based on this revelation statement indicating that God’s fiat takes primary direction (view 11; Leviticus 27:11–12, 26–27; Numbers 18:15). Expanding this process, Pharisaic and the Rabbinic theology expanded this kosher pattern beyond the presented lists to retain ritual cleanness during everyday life (Acts 11:2–3).62

An additional feature to notice is that the animals created on day six that are not to be eaten are merely “unclean”, whereas, the animals created on day five not to be eaten are lower than unclean, they are “detestable” (Leviticus 11:4–43). Thus an ontological creation hierarchy (or chain of being elevating land animals over those of air and water) is retained among the kosher lists that might have been set up in the Creation account (elevating animals of day six creation over those animals created on day five).

Being “unclean” essentially means being in a metaphysical condition of inappropriateness for cult participation. Such uncleanness is not sin for the condition may be caused naturally without doing any inappropriate deed. For example, a human with scale disease or leprosy, or a mildew on a garment or house is not caused by deeds (Leviticus 13:3–14:57). Such a condition simply presents itself and needs to be noticed and appropriately acted upon or it excludes people from cultic participation. In this, the priest tries to determine the nature of the metaphysical condition. If the priest appraises a person as unclean then the unclean person is isolated outside the exodus camp with a weekly reappraisal until the healing begins. If a priest appraises an object as unclean then it is thoroughly scoured to cleanse it. If a priest considers a person or object as perpetually unclean then that person must dwell perpetually outside the camp (Leviticus 13:3, 45–46; 14:8–11; Numbers 5:2–4)63 and perpetually unclean objects must be destroyed as inappropriate. Such severity about living outside the camp reflects that the exodus camp is as though Israel is perpetually on pilgrimage, being in close proximity to the tabernacle and the functioning cult. While all Jewish teaching excluded such unclean from the Temple and cult, once Israelites spread out throughout the land, the leper could live within the lands since they were later permitted to attend synagogue (for example, 2 Chronicles 23:19) (Yadin 1977–1983, 1:277–343).64 However, lepers were a social and religious pariah, needing to avoid social settings and to call out “unclean, unclean” so that other Israelites would not touch them inadvertently and become themselves unclean (Leviticus 5:3; 13:11, 33, 45–46; Numbers 5:2–4; 1 Samuel 20:26).65 Additionally, the leper was to have torn clothes and disheveled hair, which are the signs of mourning a death (Leviticus 10:6; 13:45–46).66 In this case, the leper is mourning his own death because such illnesses draw the victim into the shadow land between life and death. A further example is Miriam who in her leprosy is compared to a still birth half decomposed and she in her cleansing is treated for impurity as having been in contact with a corpse (Numbers 12:12) (Frymer-Kensky 1983, pp. 399–414, especially p. 400).

Uncleanness is a communicable disease which is transferred by touch and close proximity. For example, contact with the blood of birth or menstruation or with bodily discharges renders one ontologically unclean (Leviticus 12:2; 15:2–33; Deuteronomy 23:10; Ezekiel 22:10; Luke 2:22–23). In such a condition, Jesus and Mary were cleansed from their uncleanness according to the Law, and obviously neither had sinned in the birthing process to become unclean (Luke 2:22–23).

Humans and animals that even ignorantly touch or eat an unclean thing become unclean and continue to communicate uncleanness by touch to other things (Leviticus 5:2–3; 7:19–21; 11:4–8, 24, 39, 44, 47; 15:4–12, 19–27; 17:15; 18:19; 20:25; 22:4–8; Numbers 19:11, 16, 22: Haggai 2:12–13).67 In fact, on rare occasions like the death of a human within a tent, everyone who enters the tent and all open vessels in the tent are rendered unclean as by an airborne contaminant (Numbers 19:14–15).68 Such transferability of uncleanness renders the derived unclean object unclean by proximity by often not as unclean as the source. For example, sometimes the source is permanent in uncleanness like the dead or a kind of animal. Other times, the remedy of an unclean source may be just more severe (like washings, seven days and two sacrifices) than the remedy of derived uncleanness (washing and one day, Leviticus 15:4–27). However, various instances of derived uncleanness from the same source are equally unclean with the same remedy. Whereas, there are different levels of derived uncleanness as evident by touching a dead body requires seven days to remedy and touching an unclean thing requires one day to remedy (Numbers 19:11–12; Leviticus 15:4–27).69 However, there are some things (like clay pots and stoves) that have an especially porous quality with regard to uncleanness and can never be purified so they must be destroyed to remove their uncleanness (Leviticus 11:33–35; 15:12). In contrast, there are some things (like water and seed) that have an especially resistant quality with regard to uncleanness, such that even a dead body touching them does not render them unclean (Leviticus 11:36–37).

The rabbis present uncleanness as communicable through a spiritual process akin to demonization for those pagans who have such within their worldviews but for a Jewish audience with a fuller biblical worldview, the communicability of uncleanness is merely grounded in the declaration of God. For example, Rabban Yohanan to the pagans says, “a man who is defiled by contact with a corpse—he, too, is possessed by a spirit, the spirit of uncleanness.”70 However, his Jewish disciples recognized that this was a simplistic answer so they asked him again to explain communicable uncleanness. To the Jewishly informed Rabban Yohanan indicated that defilement and cleansing were ultimately grounded in God.

By your lives, I swear: the corpse does not have the power by itself to defile, nor does the mixture of ash and water have the power by itself to cleanse. The truth is that purifying power of the Red Cow is a decree of the Holy One. The Holy One said: “I have set it down as a statue, I have it as a decree. You are not permitted to transgress my decree. ‘This is the statue of the Torah (Numbers 19:1).’”71

So once again, within a Jewish worldview, the concepts of clean and unclean are held in metaphysical place by God’s power and fiat.

Uncleanness also affects the Temple and cult as an airborne contaminant. Jacob Milgrom led a reappraisal of the effect of the concept of ontological uncleanness through his metaphor of the picture of Dorian Gray. The Oscar Wilde novel The Picture of Dorian Gray portrays an individual adventurer who did not age or suffer the consequences of his adventures, for they all were marked upon his picture until the two met in his self destruction (Wilde 1890). One may say of the priestly picture of Dorian Gray, uncleanness may not leave its mark on the face of the unclean but it is certain to mark the face of the sanctuary; and unless it is quickly expunged, God’s presence will depart.72

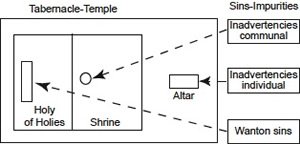

For Israel to ignore this warning and to become unclean defiles the tabernacle putting themselves at risk to be cut off in covenant curse (Leviticus 15:31; Numbers 19:13).73 This defilement of tabernacle penetrates to defile the holy place and altar as well (Leviticus 16:16, 18; Numbers 19:20). For example, high-handed unrepentant sin, such as refusing to purify oneself after touching a dead body defiles both tabernacle and the holy place (Numbers 19:13, 20). Some might think that the tabernacle and the holy place are interchangeable on the basis of Numbers 19:13, 20 but they are better to be seen as different aspects of the tabernacle as is apparent in Leviticus 16:16–20 where the effect of uncleanness is developed again and the holy place, the tent of meeting and the altar are all distinguished. In recognizing this, Jacob Milgrom presents uncleanness defiling the tabernacle in three stages (Milgrom 1990, pp. 445–446). (1) The individual’s inadvertent misdemeanor or severe physical impurity defiles the courtyard altar, which is cleansed by daubing its horns with the blood of the purification offering (Leviticus 4:25, 30; 99:9). (2) The inadvertent misdemeanor of the High Priest or the entire community pollutes the Shrine, which is purged by the high Priest placing the purification offering blood on the inner altar and before the veil that divides the Holy place from the Holy of Holies (Leviticus 4:5–7, 16–18). (3) High handed, unrepentant sin not only pollutes the outer altar and penetrates into the Holy place, but also pierces the veil to the Holy of Holies and the holy ark, the throne of God on earth (Leviticus 16:16; Numbers 19:20; Isaiah 37:16). Since the high handed, rebellious sinner is barred from bringing a purification offering (Numbers 15:27–31), the uncleanness wrought by his offense must await the cleansing of the sanctuary on the Day of Atonement, which consists of two steps; the cleansing of the tent, and the cleansing of the outer altar, and the people the atonement (Leviticus 16: 16–19, 30). Thus all that is most holy is cleansed on the Day of Atonement with purification offering blood. Thus, the graduated cleansings of the sanctuary lead to the conclusion that the severity of sin and uncleanness varies in direct relation to depth of its penetration into the sanctuary as shown in Milgrom’s diagram (Milgrom 1990, p. 50; 1991a, p. 258) shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Diagram of sanctuary contamination.

Milgrom summarizes this Sanctuary contamination through three laws. (1) “Sancta contamination varies directly with the charge (holiness) of the sanctuary, the charge of the impurity, and inversely with the distance between them” (Milgrom 1992, pp. 137–146, especially p. 142). This law is an application by Milgrom of Mesopotamian contamination of the cult through airborne impurity. However, Yahweh’s cult is extremely holy, so it is highly sensitive to contamination in the camp (Deuteronomy 23:15). Thus there are repeated warnings to not pollute the sanctuary, which would bring destruction from Yahweh (Leviticus 12:4; 15:31; 20:1–4; Numbers 19:13, 20). By observation and comparison, Milgrom proposes a second law: (2) “Impurity displaces an equal amount of sanctuary holiness” (Milgrom 1992, pp. 142–143). Holiness is being treated as an ontological thing which can be displaced. God will tolerate inadvertent wrongs which contaminate the outside altar and shrine for they can be purged through purification offerings (Leviticus 4:1–35). However, there is no sacrifice for defiant and rebellious acts, so the nation must purify the sanctuary of these on the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16 especially verses 10, 16, 20–22; Numbers 15:30). To not comply with such purgation forces God’s departure from the contaminated Temple as a result of Israel’s sin (

(3) Thus, the pre- and post-ablution periods offer a new criterion for comparing the realms of the sacred and the common, to wit: (a) The sacred is of greater sensitivity to contamination than the common by one degree, and (b) each purification stage reduces contagion to both the sacred and the common by one degree. There are three possibilities to contaminate an object: from afar, by direct contact, or at home. Specifically, a severely impure person contaminates a common object by direct contact and a sacred object from afar. After the ablution, he is no longer contagious to the common object but can contaminate a sacred object by direct contact (but no from afar). Finally, after the last stage of purification he is no longer contagious even to sancta (Milgrom 1986a; 1986b pp. 115–120; 1992).

Such a summary for how uncleanness contaminates and is purified is warranted by the biblical examples, Josephus and tannaitic sources (Leviticus 11–16).74 The purgation will be developed at greater depth under the section concerning sacrifice.

Furthermore, any form of uncleanness defiles the land. For example, a dead body hanging overnight defiles the land which Yahweh gives Israel as an inheritance (Deuteronomy 21:23). Likewise, by not killing murderers by capital punishment, the land is defiled and threatens Yahweh’s continuing dwelling with Israel (Numbers 35:34). Furthermore, for Israel to flagrantly defile themselves by sensuality and pagan worship defiles the land and places Israel at risk of Yahweh’s covenant curse in the same manner as He cursed the people of the land of their idolatry (Leviticus 18:24–30).

The means of purification involves washing in specially prepared water and fulfilling the time of uncleanness. The water to remove impurity is prepared by mixing the ashes of the red heifer burnt offering, cedar wood, hyssop, and scarlet material together in the water (Numbers 19:1–10). Those involved in preparing this water for cleansing become clean, namely the priest who sacrifices this offering and the man who gathers the ashes (Numbers 19:7, 10). These unclean utilize the water for cleansing to wash themselves and their clothes and are unclean until evening. Anyone who touches or is inside a tent with a dead body is required to purify himself by washing in the water for cleansing on the third and seventh days and is unclean until the seventh day (Numbers 19:11–13, 18–19).75 Such purifying means are also involved in cleansing the spoil from battle with the Midianites (Numbers 31:23–24). The one who sprinkles the water for cleansing shall be unclean till evening and then he too must wash himself and clothes in the water for cleansing (Numbers 19: 21–22). The one who refuses to cleanse himself through the water of cleansing defiles the tabernacle and is destined to cut off.

Sacrifice is only to utilize clean offerings and sites. For example, Noah sacrificed only clean animals (Genesis 8:20). Furthermore, the purification offering is a clean sacrifice with the ashes poured out outside the camp in a clean place (Leviticus 4:12; 6:11). There is no alternative altar for cleansing than the tabernacle, or Israel is under threat of being cut off (Joshua 22: 16–20). Doing any ritual as a priest or eating a sacrifice or touching a holy gift in an unclean ontological condition or place threatens the cult with uncleanness thus rendering one guilty to be cut off from the people (Leviticus 7:19–21; 10:9–10, 14; Numbers 18:11, 13; Deuteronomy 26:14). Such recognition raises the need for an alternative date for celebrating Passover by the momentarily unclean person who misses the normal Passover date (Number 9:6–10). However, if someone was clean and skipped Passover then they are without excuse and shall be cut off (Numbers 9:13–14). On the other hand, when the ignorant ate Passover in an unclean condition, merciful Yahweh atoned for them in response to Hezekiah’s revival and prayer on their behalf (2 Chronicles 30:17–19). However, it is far better to operate as Zerubabel’s revival by first cleansing all the people so that they could participate in passover Ezra 2:20–21.

On an individual level, the recovery process for the individual takes time, washing, and sacrifice to recover the unclean to clean status. For example, if the scale disease or mildew begins to heal then there is an elaborate process of cleansing showing ultimately that God superintends the healing process which reelevates the unclean to the metaphysical clean status. The process includes offering two clean birds, one to die and the other to go free. The unclean one is sprinkled with the blood of the slain bird which elevates him to a level of cleanness, while not wholly clean. The unclean are to wash their clothes, themselves, and shave their hair, which renders the person clean to enter the camp but not his tent (Leviticus 14:8). Two male lambs (or pigeons for the poor) with the respective grain offerings are offered on the eighth day as a guilt offering and a purification offering, and then the healed leper is further clean (Leviticus 14:9). Following this process, the priest announces the person or object as further clean, putting blood on the earlobe and anointing the healed with oil (Leviticus 14:20). This process is progressively cleansing with clean operating on different levels of cleanliness. This process is not magical as evidence by the absence of any incantation, which are so common in magic scrolls. Furthermore, God can cleanse a person with scale disease, like Naaman any way He desires, including seven dips in the Jordan River (2 Kings 5:14). However, the elaborate rituals of appraisal and cleansing accentuate the distinctively separate metaphysical levels of clean from unclean.

Within the Mosaic Covenant, Yahweh demands that Israel be kept clean and holy (Leviticus 11:44–45). Only clean people can participate in cultic functions (Leviticus 7:19–20; 1 Samuel 20:26; Ezra 6:20; and an exception in 2 Chronicles 30:17–19 which has God supernaturally cleanse Israel also supports the rule). If Israel does not deal with their uncleanness, then it becomes a sin. For Israel to ignore this mandate and to become unclean defiles the Tabernacle and puts Israel at risk to be cut off in covenant curse (Leviticus 15:31; Numbers 19:13). This defilement of Tabernacle from Israel’s uncleanness includes the Holy Place and altar as well (Leviticus 16:16, 18; Numbers 19:20). Ultimately, sins defile Yahweh’s holy name and bring covenant curse as was previously developed (Deuteronomy 28:15–29:29; Ezekiel 43:7–8). For example, the high-handed unrepentant sin, such as refusing to purify oneself after touching a dead body defiles both Tabernacle and Holy Place (Numbers 19:13, 20). Furthermore, one of the sins for which Israel is condemned to the Babylonian captivity is the sin of the priest’s failure to teach the people and to practice the difference between clean and unclean (Ezekiel 22:26; Haggai 2:11–14).

Whatever standard God sets metaphysically for clean becomes what is appropriate. The ontologically unclean cannot be rendered clean by human means (Job 14:4). No attempt at viewing or externally fulfilling purifying rituals can render the metaphysically unclean into clean status (Proverbs 30:12; Isaiah 66:17).

Verbally, words that are refined and helpful are “pure” (thr, Psalm 12:6; Proverbs 15:26). Obedience to such “pure” (thr) teaching preserves a person from sin allowing them to continue to be ontologically clean (Psalm 12:6–7). Whereas, lying words are (tm’) but can be forgiven through Yahweh’s refining process (Isaiah 6:5). However, if a life habituates in sin, no amount of claiming such an ontologically clean status can remove a person’s sins (Proverbs 20:9).