The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

The authors demonstrate a plausible revision of the first seven centuries and 14 dynasties of Egyptian history from the Dispersion to the Exodus using all available historical sources, which will be seen to resolve several problems with reconciling Egyptian history with the Masoretic Text of Scripture for the Sojourn in Egypt.

Keywords: Egyptian Chronology, Sojourn in Egypt, Ussher Chronology, CFAH, Chronological Framework of Ancient History

Introduction

This paper is the sixth in the Chronological Framework of Ancient History (CFAH) series and the first of a two-part paper presenting an alternative chronology for the seven centuries of Egyptian history from the Dispersion in 2191 BC until the Exodus in 1491 BC.

Through this series of 20 papers the authors have been developing a comprehensive revisionist Chronological Framework of Ancient History (CFAH) by filtering the durations between events recorded by ancient chroniclers and their copyists through the critical method explained in the first paper, Griffith and White (2022a). The ancient chroniclers claimed access to accurate information about the past from temple and state records. The focus of the CFAH series is to build a historical model based on the classical chroniclers that is integrated with Scripture. We accept the chroniclers’ durations to events when we find that two or three witnesses agree.

We confirmed in papers Griffith and White (2022b; 2023a; 2023b) that eight ancient cultures agreed closely on the dates of Babel, the Dispersion, or the founding date of their nations (Griffith and White 2022b; 2023a, b). We saw in Griffith and White (2023c) that some official chroniclers such as Berossus used sophisticated methods such as a checksum to preserve the data in their chronology.

It is important to note at the outset that historical arguments are usually inductive rather than deductive (Lisle 2009, 107). Due to the lack of comprehensive information, the best that any scholar can present is a possible or reasonably probable chronology of the ancient world.

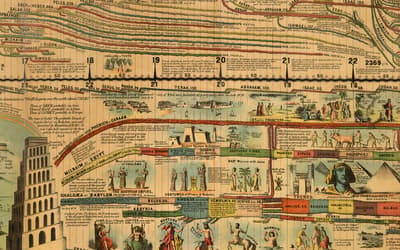

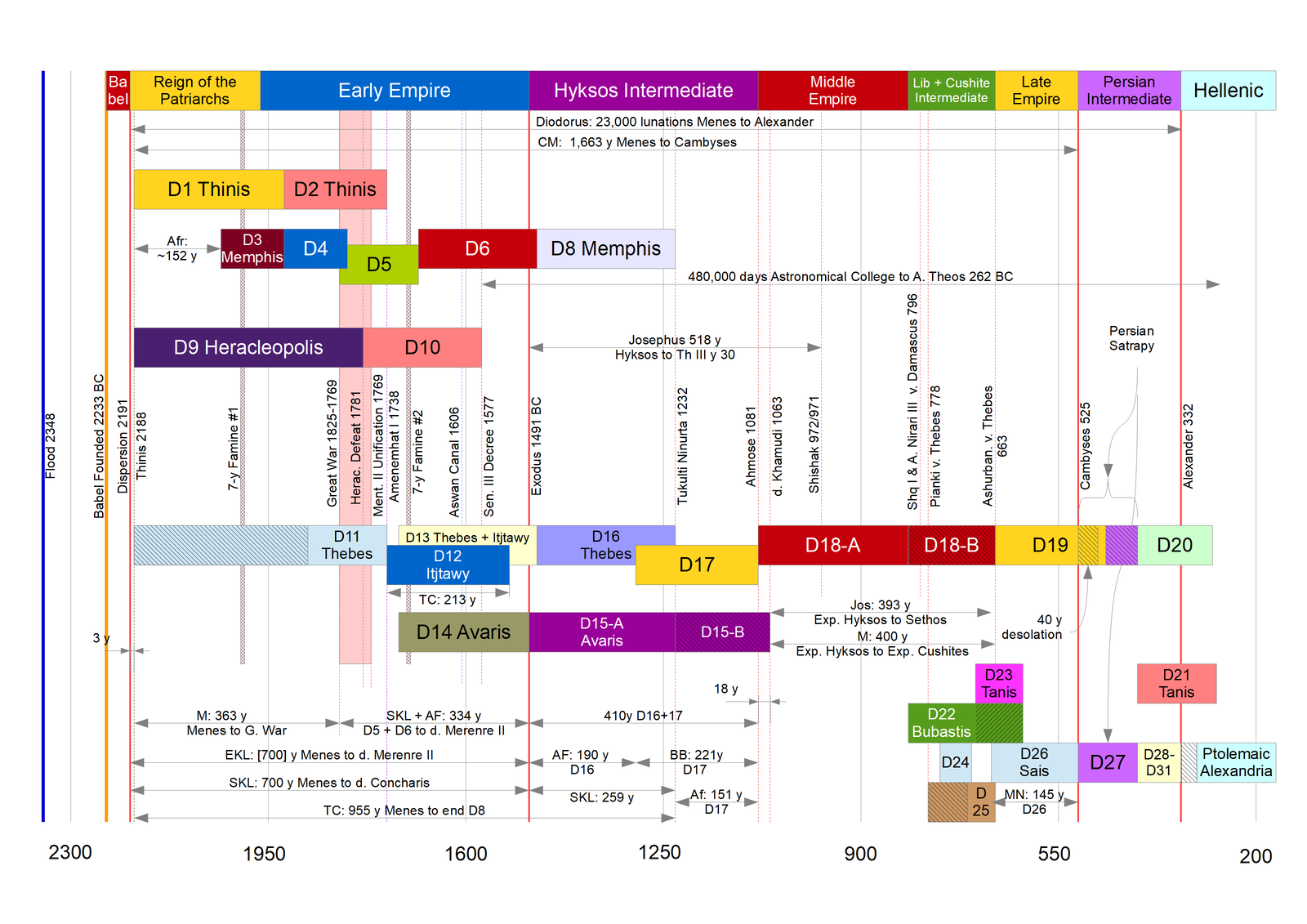

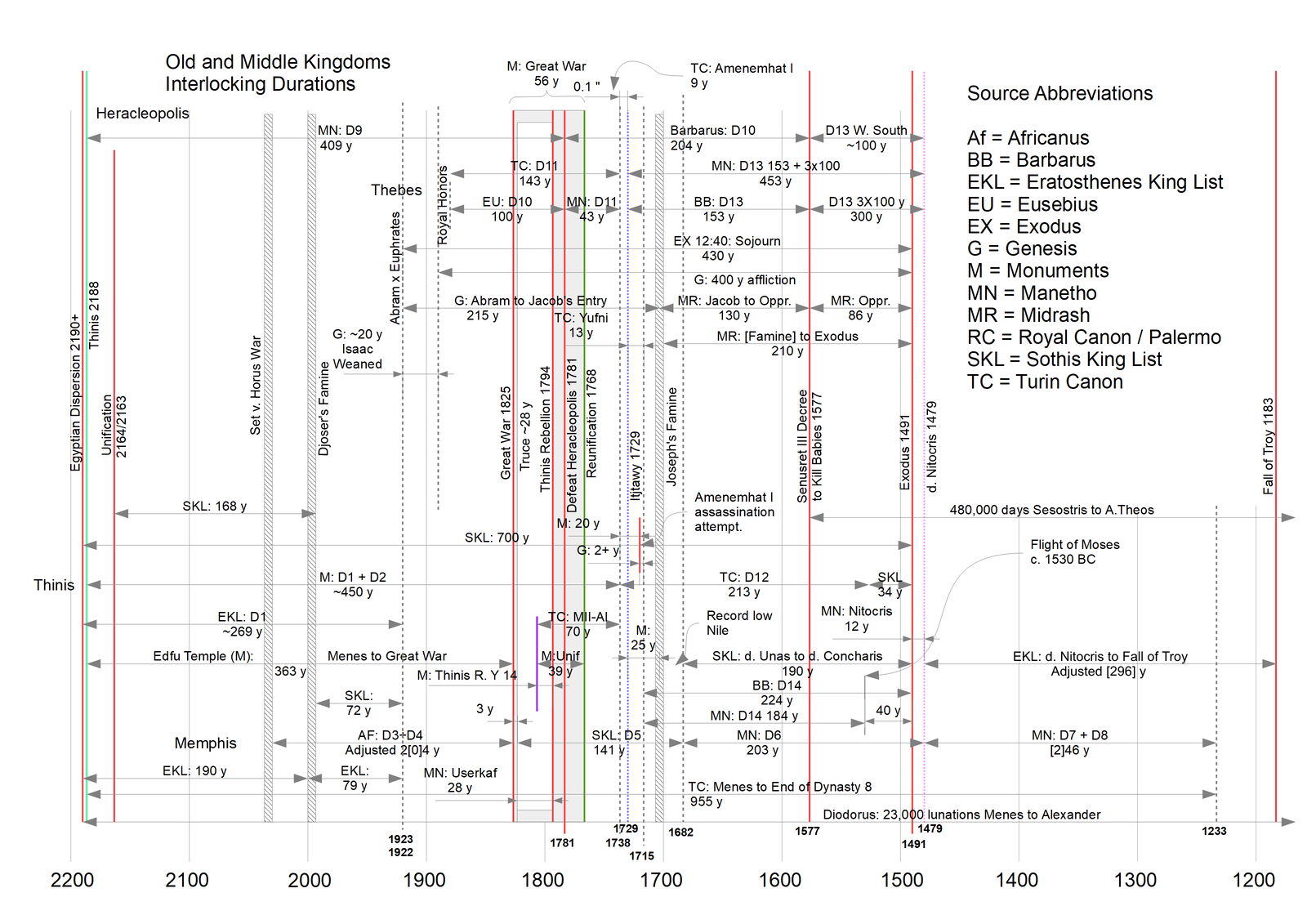

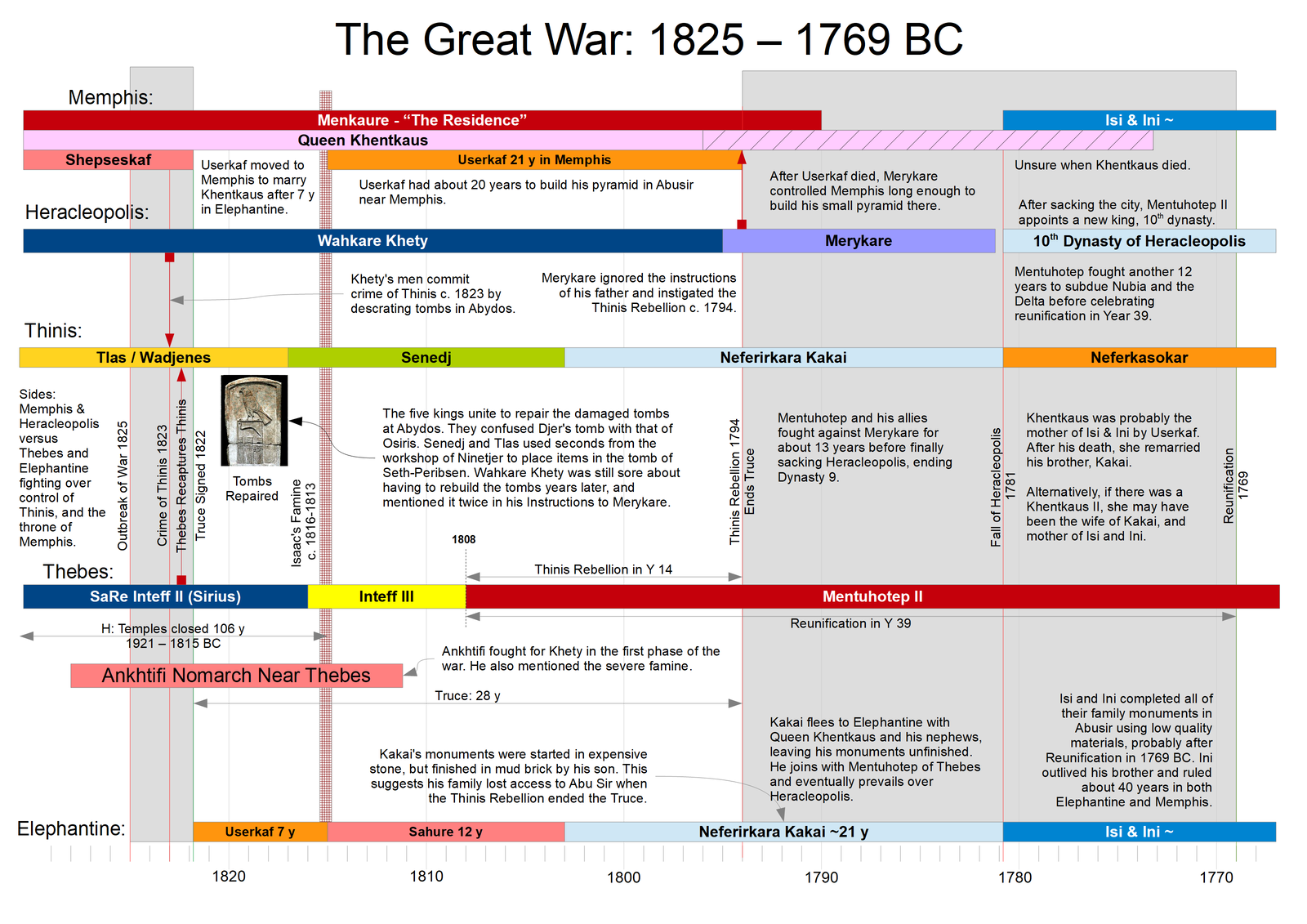

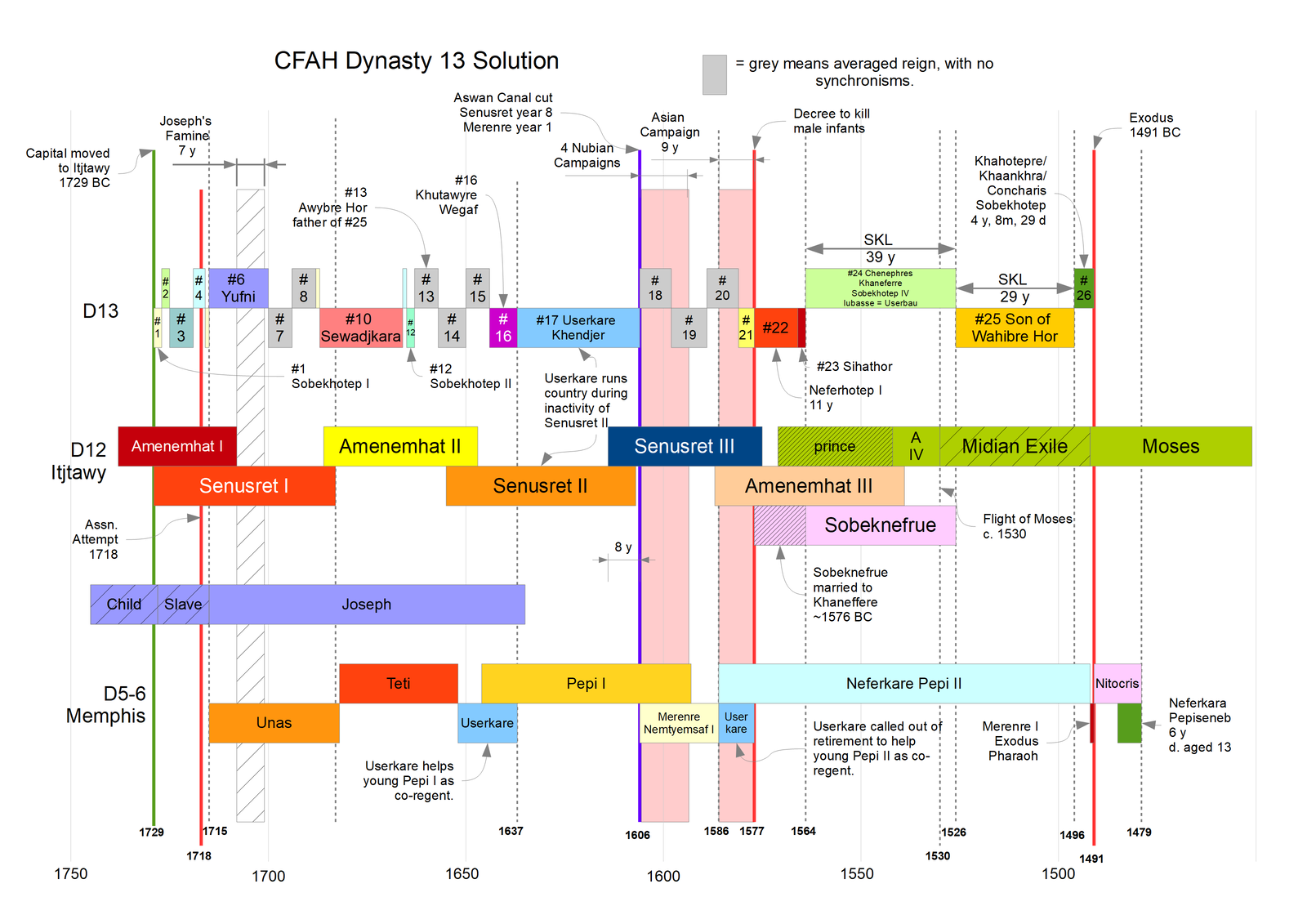

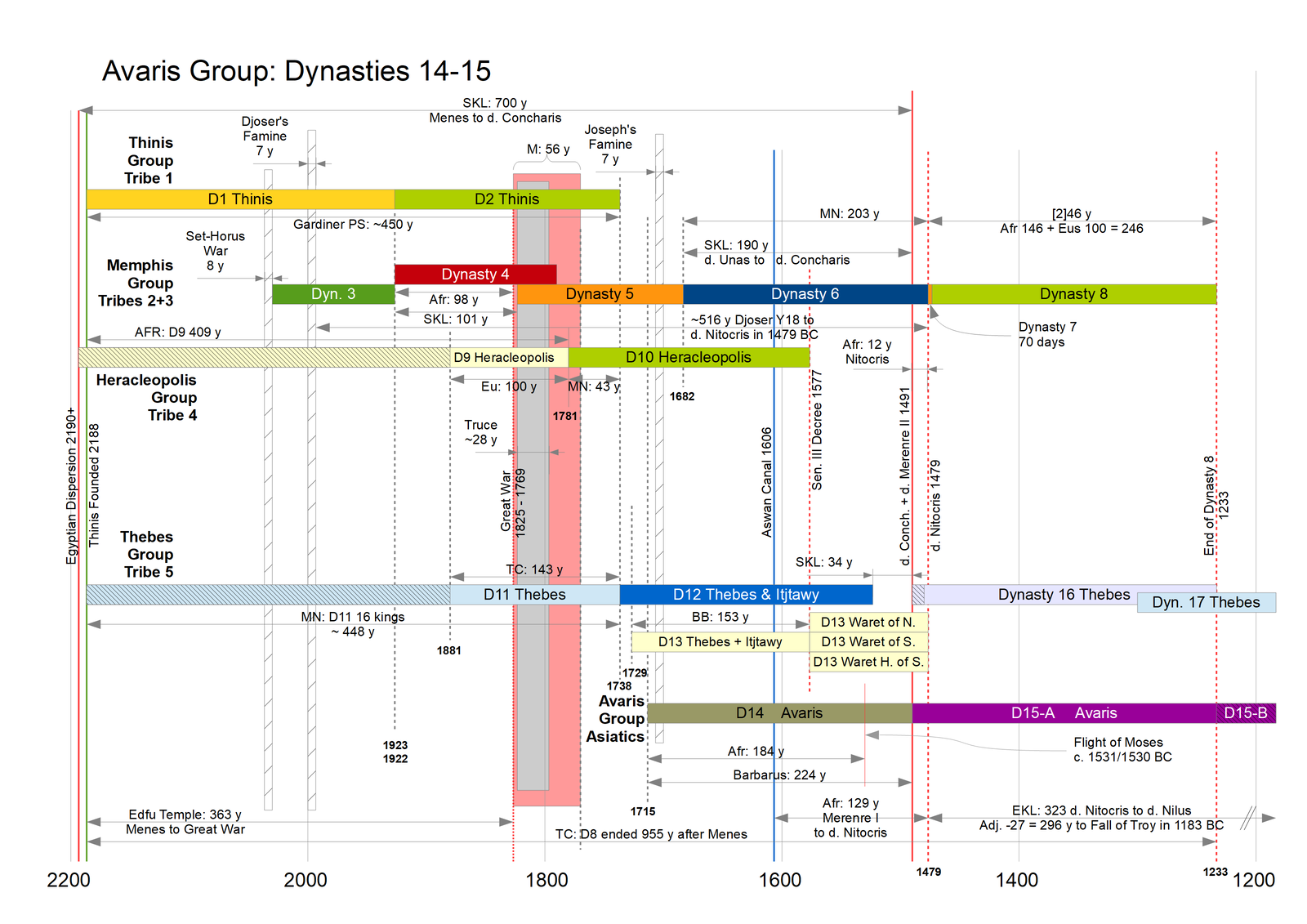

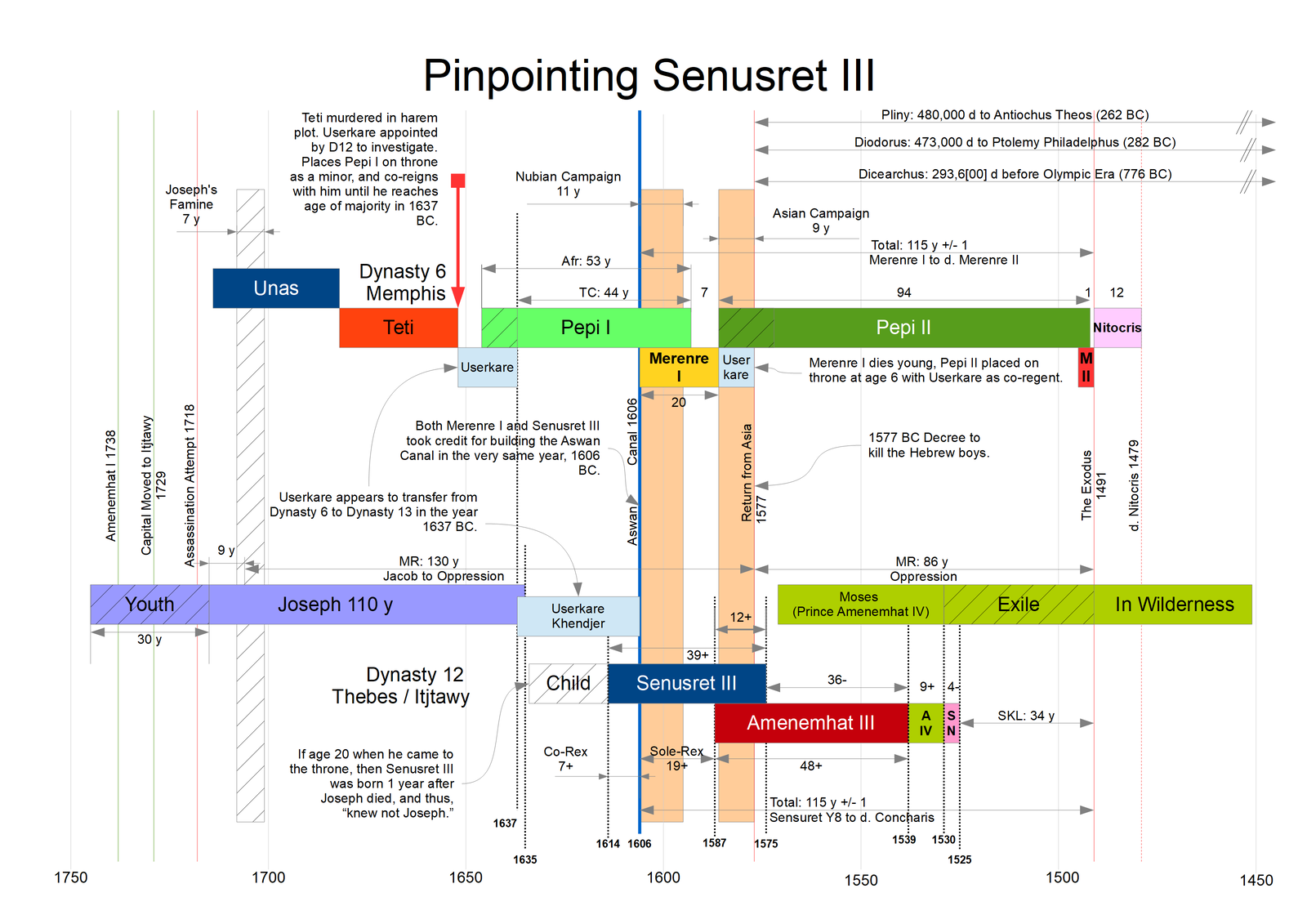

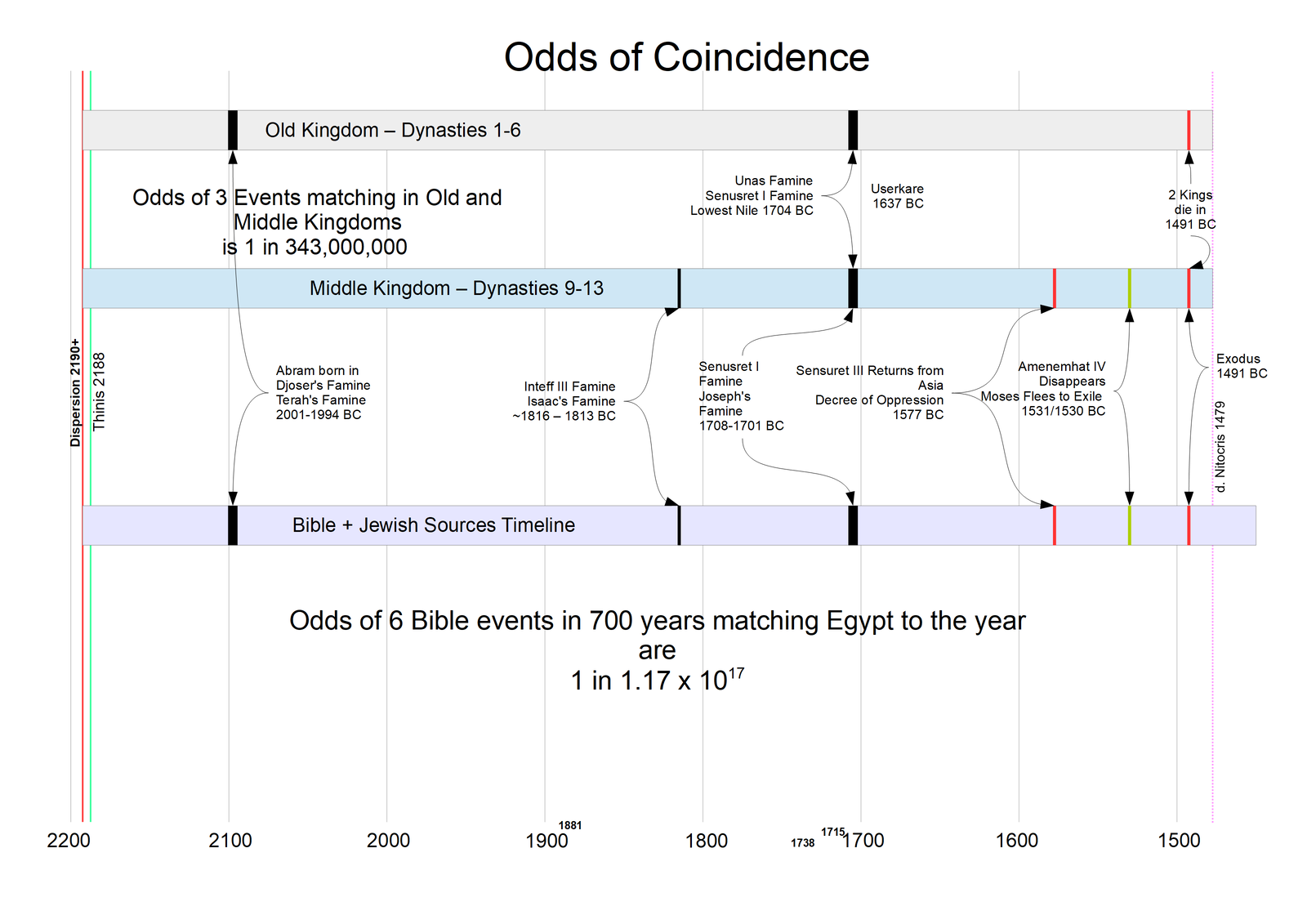

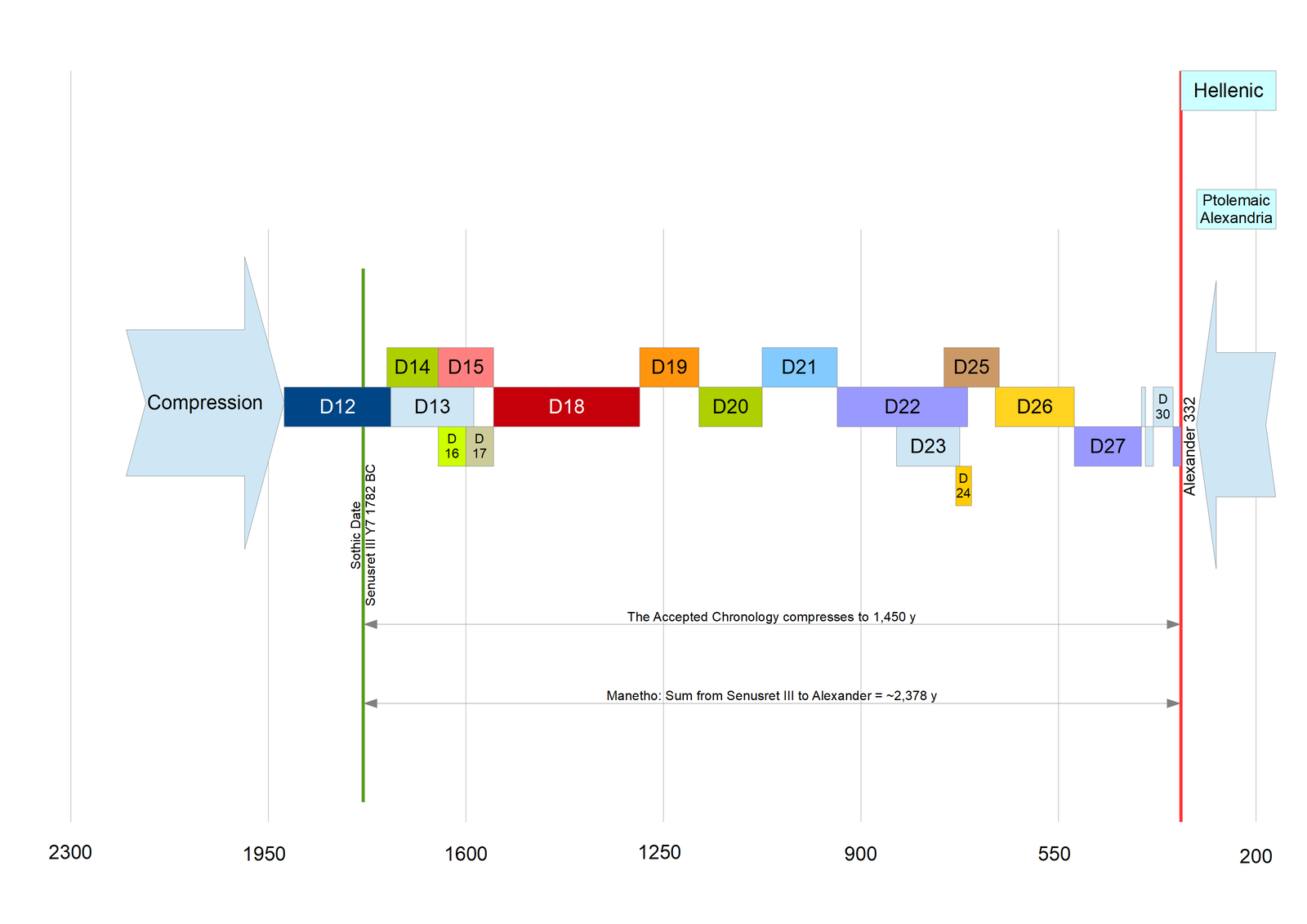

Fig. 1 shows an overview of the entire CFAH model for Egyptian history, which will be argued in papers #6 through #12. For the first seven centuries of Egyptian history, our model extends that of Courville (1971) with a few differences.

Fig. 1. CFAH Egyptian chronology.

The scope of this paper is to pinpoint the placements of Dynasties #1 through #14, which fit in the nine and a half centuries between the Dispersion in 2191 BC, and the end of Dynasty 8 circa 1233 BC. It would take a 400 page book to fully develop the thesis of this paper. As we must reduce the paper to a readable length, we will have to summarize our arguments and research here.

Using All Available Historical Sources

The data for this paper is composed of durations for dynasties and events in Egypt from The Turin Canon (TC), Manetho, the Sothis King List (SKL), the Eratosthenes King List (EKL), the Old Egyptian Chronicle, Josephus, Artapanus, the Book of Jubilees, and the Midrash, as well as monumental inscriptions and papyri.

There are six extant redactions of Manetho’s Aegyptiaca by Africanus, Eusebius, the Armenian text of Eusebius, Josephus, Theophilus, and Barbarus. When citing any of those six sources, we are referring to Manetho. Appendix 1 defends the use of these sources and presents a working hypothesis of the method Manetho used to compose his lists, which was that he listed city dynasties by groups in the order in which they came to power.

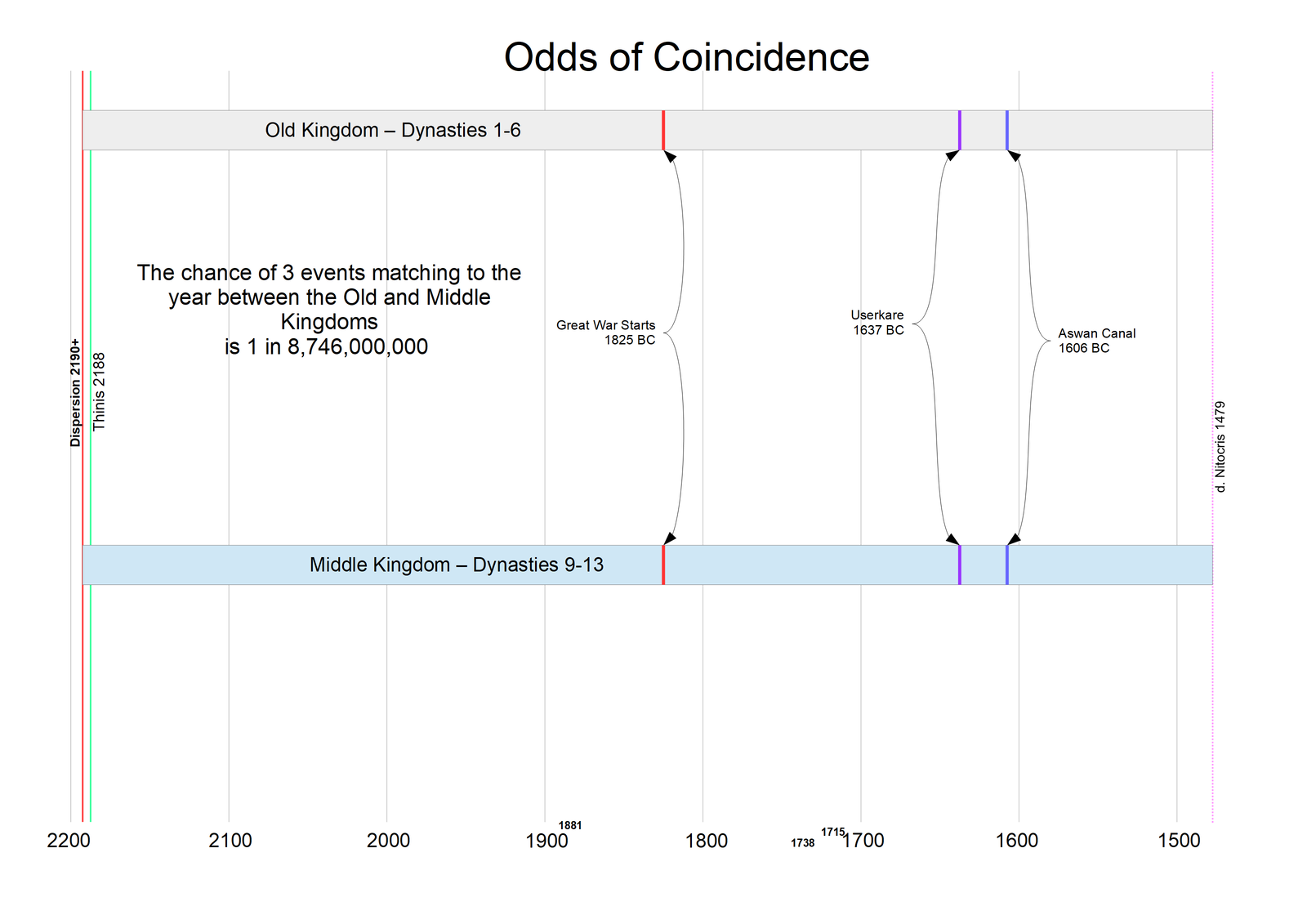

Arguments for the CFAH Model of Egyptian History

We offer the following arguments that Manetho’s original work was understood by the initiated priesthood to represent overlapping dynasties reigning in different cities at the same time but was deliberately misrepresented to the uninitiated Greeks as a single chronological series from Menes to Alexander. First, the widespread and normal means of administering nations in the Bronze Age was the Great King and Vassal King covenant, which would naturally produce parallel dynasties as seen in the Sumerian King List. Second, the durations of the dynasties from the priestly sources can be shown to fit together and interlock so that the parallel dynasties fit together sensibly and harmonize the majority of the data. Third, the resulting synchronisms between Egyptian dynasties are surprisingly accurate. Fourth, we find several precise synchronisms with Scripture that support our placement of the dynasties as plausible. Fifth, the synchronisms that arise from this placement expand our knowledge of Egyptian history, and the probability of such synchronisms resulting from chance is infinitesimally small.

Argument 1. Great Kings with Vassals Were the Default Polity

During most periods of Egyptian history, one city was dominant over the others, thus creating a “great king” and vassal king arrangement governed by a suzerain treaty (Coogan 2009, 100) which was common in the Near East down to the end of the Middle Ages.

Therefore, when we look at the ANE society of polities, we notice the co-existence of city-states, whose purpose was to operate as a divine manor, and national states, whose purpose was to function as a reflection of divine king-ship. This yields a two-tier system in which it is understood that the gods decree their favour on a great king who, in turn, is acknowledged as the ruler of an hegemonic national state, the legitimate suzerain of vassal lesser kings, enjoying certain privileges and system-wide responsibilities. (Freire 2015, 9)

We find several confirmations of this claim from different periods of Egyptian history. First, Artapanus wrote that at the time Moses was born:

[King Palmanothes] begat a daughter Merris, whom he betrothed to a certain Chenephres, king of the regions above Memphis (for there were at that time many kings in Egypt); and she being barren took a supposititious child from one of the Jews, and called him Mouses (Moses) . . . (Eusebius 2002, Pr.Ev.9.27, emphasis added)

Second, we learn that eight centuries later, when Piankhi conquered Lower Egypt, he found twenty kings reigning in various cities there, whose names and cities he recorded on the Piankhi Stela (Ben Tor 2010, 91–107).

Third, King Intef III, though being the King of Thebes, left an inscription calling himself, “Confidant of the King,” which Hayes (1971, 475) interpreted as meaning the King of Heracleopolis, though we will argue he was referring to “The Residence,” meaning the King of Memphis Dynasty 4.

We consider these examples sufficient to demonstrate that multiple kings were ruling simultaneously in Egypt over the major cities during at least parts of the early, middle, and late periods of Egyptian history. The major exception to this rule was the Eighteenth Dynasty for reasons that will be discussed in the future paper CFAH-8. As might be expected, the periods of multiple reigning city dynasties sometimes led to or resulted from instability and civil war.

Egyptologists recognize that several petty kings ruled in various cities in Upper Egypt during the Predynastic time period they refer to as “Dynasty 0” or the Protodynastic Period (Wilkinson 1999, 1–27). These included the kings named Iry-Hor, Scorpion I and II, and several others. However, Egyptologists tend to assume that after Narmer unified Egypt by conquest, there was only one king ruling all of Egypt at any given time for most of the following three millennia, excepting the three “intermediate periods” (Spalinger 2001, 265). However, given that Egypt spanned 1,300 km from Abu Simbel to the Mediterranean Sea, that would be like assuming that the territory from Jerusalem to Susa in Iran only had one king for most of antiquity. Given that the universal governance model in the Ancient Near East could be described as feudalism, it would make far more sense to assume that there were typically petty kings ruling local cities as vassals of a Great King, except where proven otherwise.

The key to deciphering ancient Egyptian chronology is the recognition of the biblical Mizraim as Menes, the founder of Egypt shortly after the Biblical Dispersion (Genesis 10:13–14; 50:11). It appears that Egypt’s oldest cities were founded shortly after the Dispersion from Babel (Griffith and White 2022b, Anchor Point 3) by five or seven of the sons (and grandsons) of Mizraim, depending on the source. Each son formed a tribe or city-state; and each city-state had its own series of kings, later recorded as dynasties. The forced unification of those founding tribes by Narmer is considered to be the dawn of Egyptian dynastic history (Wilkinson 1999, 28–59).

The fact that Manetho lists dynasties by city is prima facie evidence of such a feudalistic arrangement. Memphis was the administrative seat of the Egyptian state for the majority of its history. Yet, Manetho grouped and ordered his dynasties by their home cities.

Syncellus summarized his copy of Manetho saying, “Thereafter Manetho tells also of five Egyptian tribes which formed thirty dynasties . . .” (Manetho 1964, 11, 211). From at least the time of Eusebius, if not earlier, Christian and Jewish historians viewed Menes in the Egyptian king lists to be the same person as Mizraim. However, Egyptologists under Darwinist influence began to reject this idea in the nineteenth century. Eusebius, who had access to a complete copy of Manetho’s Aegyptiaca summarized:

Egypt is called Mestraim by the Hebrews; and Mestraim lived <not> long after the Flood. For after the Flood, Cham (or Ham), son of Noah, begat Aegyptus or Mestraim, who was the first to set out to establish himself in Egypt, at the time when the tribes began to disperse this way and that. . . . Mestraim was indeed the founder of the Egyptian race; and from him the First Egyptian Dynasty must be held to spring.” (Manetho 1964, 7,9)

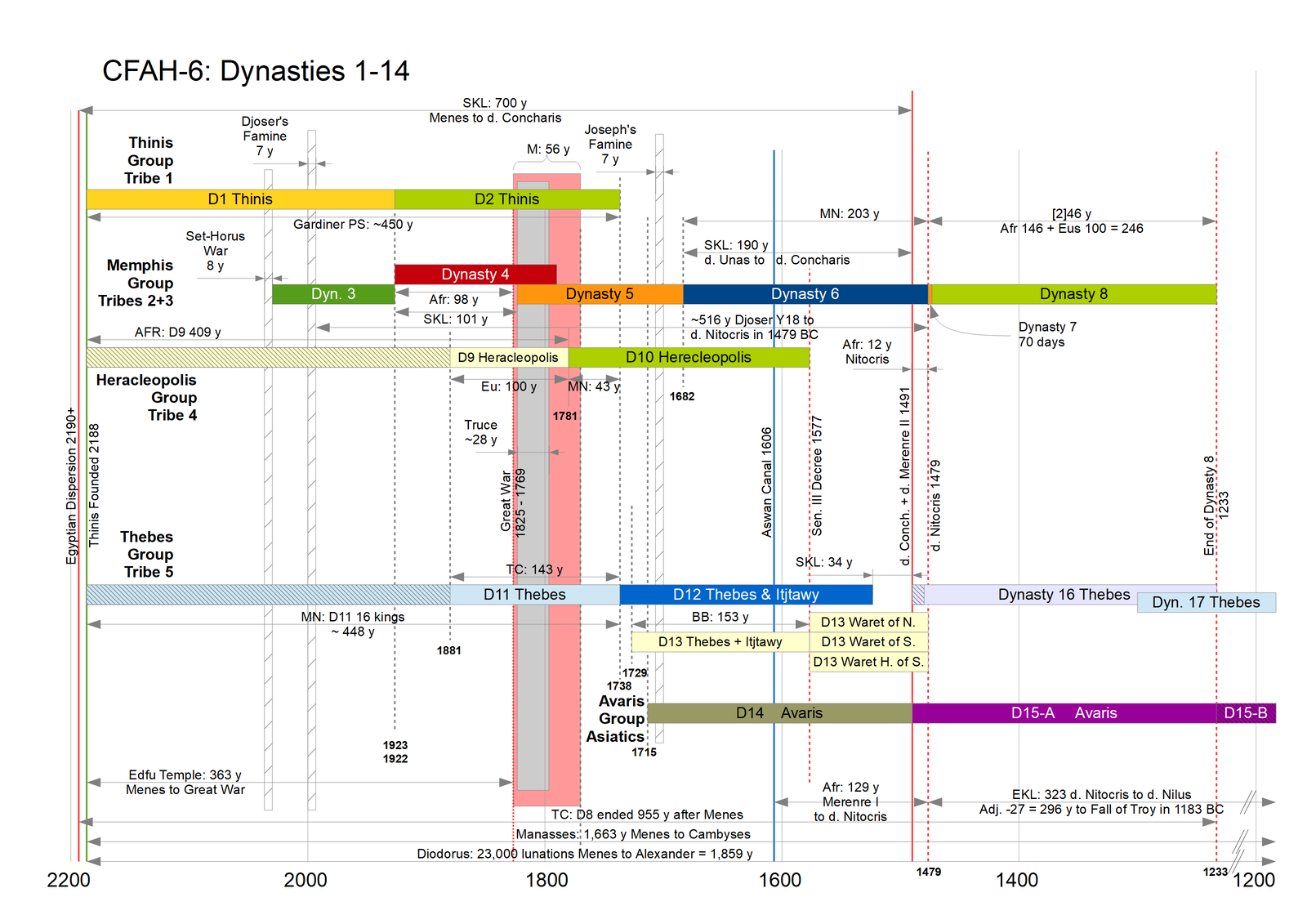

Having made a case for a Great King and Vassal arrangement in ancient Egypt, the next argument will show how the city dynasties fit together like a puzzle (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. CFAH solution for Dynasties 1–14.

Argument 2. The Durations Form an Interlocking Matrix

The durations between events in early Egyptian history provided by ancient and classical sources fit together to form an interlocking matrix (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Matrix of interlocking durations between Old and Middle Kingdom Dynasties.

Table 1 lists anchor points determined in the first five papers in addition to new ones that will be determined below. Table 2 lists dynastic durations from the main sources of Manetho and Monuments such as the Palermo Stone. Additional durations to relevant events are listed in table 3.

Table 1. Anchor Points for early Egyptian history.

| Anchor Points for Early Egyptian HistorySorted by Date | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Anchor Point # | Year BC | Event | Paper # |

| 2 | 2192/2191 | The Dispersion. The Egyptian monarchy was founded in the year of the Dispersion, probably before they migrated from Babel. | CFAH-2 |

| 3 | 2189/2188 | Egyptian state was founded with the first cities, Thinis, Nekheb, etc. | CFAH-2 |

| 22 | 2164/2163 | War of Unification, Memphis founded. | CFAH-3 |

| 21 | 2036/2035 | Start of the reign of Semiramis I | CFAH-3 |

| 50 | 2029–1922 | Dynasty 3 of Memphis, ends with death of Sneferu | CFAH-6 |

| 49 | 2001–1994 | Djoser’s Seven Year Famine | CFAH-6 |

| 20 | 1825–1769 | Great War lasted 56 years. | CFAH-3,CFAH-6 |

| 55 | 1881 | Royal Honors given to Heracleopolis and Thebes by D4 | CFAH-6 |

| 56 | 1808 | Accession of Mentuhotep II | CFAH-6 |

| 54 | 1781 | Fall of Heracleopolis to Thebes, End Dynasty 9 | CFAH-6 |

| 53 | 1738 | Accession of Amenemhat I | CFAH-6 |

| 57 | 1729 | Founding of Itjtawy, Start of Dynasty 13 | CFAH-6 |

| 60 | 1718 | Failed Assassination Attempt on Amenemhat I | CFAH-6 |

| 61 | 1716/1715 | Joseph Promoted from Prison | CFAH-6 |

| 58 | 1708–1701 | Joseph’s Famine, Senusret I Famine, Unas Famine | CFAH-6 |

| 17 | 1679 | Approximate year of death of Joseph’s pharaoh, Moeris | CFAH-3 |

| 59 | 1606 | Digging of Aswan Canal for the First Time | CFAH-6 |

| 18 | 1577/1576 | Senusret III returned from war in Asia, founded an astronomical college, and reorganized the government. | CFAH-3 |

| 52 | 1526/1525 | Death of R. Iubass, Sobekneferu, end of Dynasty 12 | CFAH-6 |

| 16 | 1497–1479 | Approximate reign of Nitocris aka Netjerkare Siptah | CFAH-3 |

| 51 | 1491 | Death of Concharis, Khaankhra Sobekhotep | CFAH-6 |

| 14 | 1233/1232 | End of Dynasty 8 of Memphis | CFAH-3 |

| 12 | 1184/1183 | Fall of Troy, Death of Nilus. | CFAH-3 |

| Key: = new Anchor Points in this paper, CFAH-6 | |||

Table 2. Dynastic durations from extant sources.

| Dynastic Durations From Extant Sources | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynasty | Africanus | Eusebius | Eusebius (Armenian) | Barbarus | Turin Canon | Palermo Stone | ||||

| Stated | Sum | Stated | Sum | Stated | Sum | |||||

| 1 | 253 | 263 | 252 | 258 | 270 | 228 | 253 | lacuna | ||

| 2 | 302 | 302 | 297 | 297 | 297 | 297 | 302 | partial | ||

| 1+2 | 555 | 549 | 1+2 = ~450(Gardiner 1964, 68) | |||||||

| 3 | 214 | 214 | 198 | n/a | 197 | n/a | 214 | |||

| 1+2+3 | 769 | 747 | ||||||||

| 4 | 277 | 284 | 448 | 448 | 277 | |||||

| 1–4 | 1046 | 1195 | ||||||||

| 5 | 248 | 218 | n/a | 258 | ||||||

| 6 | 203 | 197 | 203 | 203 | N/A | 203 | N/A | N/A | ||

| 1–6 | 1497 | 1498 | n/a | N/A | ||||||

| 7 | 70 d | 75 d | 75 y | N/A | N/A | |||||

| 8 | 146 | 100 | 100 | 140 | 187? | N/A | ||||

| 1–8 | 1639 | 1598 | 955 | N/A | ||||||

| 9 | 409 | 100 | 100 | 409 | N/A | |||||

| 10 | 185 | 185 | 185 | 204 | N/A | |||||

| 11 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 60 | 143 | N/A | ||||

| 1–11 | 2300 y, 70 d | 2300 y, 79 d | 2300 | |||||||

| 12 | 160 | 245 | N/A | 153 | 213 y, 1 m, 17d | |||||

| N/A | ||||||||||

| 13 | 453 | 453 | 453 | 184 | N/A | |||||

| 14 | 184 | 184 | 484 | 224 | N/A | |||||

|

Color Key blue = precise chronological duration green = checksum, not a chronological value red = probable copying error |

||||||||||

Table 3. Durations from other sources.

| Durations from Other Sources | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration(years) | Event 1 | Event 2 | Source | Comment |

| 700 | Dispersion 1491 | D. Concharis | Sothis King List | |

| 34 | Deaths of Chenephres and Sobekneferu | D. Concharis | Sothis King List | Sum of reigns of kings #24 and #25 |

| 130 | Jacob’s entry to Egypt | Decree of Oppression | Midrash (Ginzberg) | |

| 86 | Decree of Oppression | Exodus | Midrash (Ginzberg) | |

| 210 | Jacob | Exodus | Midrash (Ginzberg) | May count from the end of the Famine. |

| 56 | Start of War over Thinis | Mentuhotep Unification Stela y 39 | (Hayes 1971, 475, 479) | Found in the tomb of a participant, the war over Thinis lasted 56 years. |

| 51 | Accession of Mentuhotep II | D. Mentuhotep II | Turin Canon | |

| 19 | D. Mentuhotep II | Accession of Amenemhat I | Turin Canon (Lundström 2020) | |

| 190 | D. Unas | D. Concharis | Sothis King List (Manetho 1964, 235–249) | Sum of Kings #18–#25 |

| 79 | Djoser Sole-Reign | D. Sneferu | Turin Canon (Lundström 2020) | Sum of Kings 4.5–4.9 |

| 79 | Start of Famine | End D3 | EKL (Manetho 1964, 213–225) | Momcheiri the Memphite = D3 |

| 72 | End of Famine | End D3 | SKL (Manetho 1964, 235–249) | Kings #5 and #6 |

| 98 | Start D4 | End D4 | Manetho Africanus (Manetho 1964, 41–43) | Last 3 kings of Dynasty 3 |

| 101 | Start D4 | End D4 | SKL | Kings #7–#9 |

| 141 | Start D5 | D. Unas | SKL | Sum of Kings #14–#17 |

| 156 | Amenemhat II | D. Rameses Iubass | SKL | Amenemhat II to death of Khaneferre Sobekhotep |

| 14 | Mentuhotep II accession | Thinis rebellion | Monument (Hayes 1971, 467) | Thinis rebellion began in year 14 of Mentuhotep II |

| 39 | Menuthotep II accession | Reunification | Monument (Hayes 1971, 479) | Reunification celebrated in year 39 of Menuthotep II |

Given that the lengths of dynasties are relative, we must rely upon the anchor points determined in Papers #2, #3, and #5 of this series (Griffith and White 2022b; 2023a, c) as key synchronisms to serve as the framework into which the dynasties fit. All of the dates in table 1 will be shown to fit with the lengths of the dynasties and durations preserved from classical sources summarized in tables 2 and 3. Table 4 lists the first set of 23 kings from the SKL with our identifications, and table 5 lists the entire EKL with identifications. The estimated dynasty dates that arise from our solution are found in table 6.

Table 4. Sothis King List with CFAH identifications.

| Sothis King List, Kings #1-#32 with Identifications | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Name | Years | List Comment | CFAH ID | Dynasty |

| 1 | Mestraim | 35 | Menes | Menes | 1 |

| 2 | Kourodes | 63 | Athothis / Narmer | 1 | |

| 3 | Aristarchus | 34 | Kenkenes/Ka Sekhen | 1 | |

| 4 | Spanius | 36 | Djet or Den | 1 | |

| 5 | two | Two kings unrecorded 72 y | Semerkhet | 1 | |

| 6 | kings | 72 | Qaa | 1 | |

| 7 | Osiropus | 23 | Khufu or Djedefre | 4 | |

| 8 | Sesonchosis | 49 | Khafre | 4 | |

| 9 | Amenemes | 29 | Menkaure | 4 | |

| 10 | Amasis | 2 | ? | 4 | |

| 11 | Acesephthres | 13 | Binothres ? | 4 | |

| 12 | Anchoreus | 9 | Shepseskaf ? | 4 | |

| 13 | Armiyses | 4 | Thampthis ? | 4 | |

| 14 | Chamois | 12 | Userkaf | 5 | |

| 15 | Miamus | 14 | Sahure | 5 | |

| 16 | Amesesis | 65 | Composite | 5 | |

| 17 | Uses | 50 | Unas | 5 | |

| 18 | Rameses | 29 | Senusret I 1 | 12 | |

| 19 | Rames(s) omenes | 15 | Amenemhat II 2 | 12 | |

| 20 | Usimares | 31 | Userkare Khendjer | 13 | |

| 21 | Ramesseseos | 23 | Senusret III | 12 | |

| 22 | Ramessameno | 19 | Amenemhat III | 12 | |

| 23 | Ramesse Iubasse | 39 | Userbau Khaneferre Sobekhotep III | 13 | |

| 24 | Ramesse | 29 | Son of Uaphres | Son of Awibre Hor | 13 |

| 25 | Concharis | 5 | Fifth year 700 years from Menes 3 | Khaankhra Sobekhotep IV | 13 |

| 26 | Silites | 19 | First of six kings of seventeenth [sic] dynasty of Manetho 4 | Saul of Rehoboth | 15 |

| 27 | Bnon | 44 | Baal Hanaan | 15 | |

| 28 | Apachnas | 36 | 15 | ||

| 29 | Apophis | 61 | 15 | ||

| 30 | Sethos | 50 | 15 | ||

| 31 | Certos | 29/44 | Josephus 29, Manetho 44 | 15 | |

| 32 | Aseth | 20 | Added 5 intercalary days | 15 | |

| Total | 959 | ||||

|

1 Name appears downshifted using regnal length of Amenemhat II 2 Name appears downshifted using active reign of Senusret II 3 Khahotepre in the Turin Canon 4 He seems to mean the Fifteenth Dynasty as listed in Canonical Manetho = Dynasty 4 Overlapping sons of Khufu, Khafre, Menkaure = Dynasty 13 Kings |

|||||

Table 5. Eratosthenes King List (EKL) with CFAH identifications.

| Eratosthenes King List with Identifications | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Name | Years | List Comment | CFAH ID | Dynasty |

| 1 | Menes | 2 | Of Thebes, name means “everlasting” | Iry-Hor/Hor-Aha?/Mizraim | 1 |

| 2 | Athothes I | 59 | “Born of Hermes” | Narmer/Hor-Aha? | 1 |

| 3 | Athothes II | 32 | Ka Sekhen/Kenkenes | 1 | |

| 4 | Miabaes | 9 | “Bull Lover” | Den? | 1 |

| 5 | Pemphos | 18 | Semphos, Semempses | Semerkhet | 1 |

| 6 | Momcheiri | 79 | of Memphis, “Leader of men” | Memphite composite D3 | 3 |

| 7 | Stoichos | 6 | “Unfeeling Aries” | Khufu? or Kawab? | 4 |

| 8 | Gosormies | 30 | “all-demanding” | Djedefre? | 4 |

| 9 | Mares | 26 | “Gift of the sun” | Mentuhotep I | 11 |

| 10 | Anoyphis | 20 | “revelling” | Inteff I | 11 |

| 11 | Sirius | 18 | “Unharmed by evil eye” | Sa-Ra Inteff II | 11 |

| 12 | Chnubos | 22 | “Golden son” | Nakht neb tep-nefer Inteff III | 11 |

| 13 | Rayosis | 13 | “The arch-masterful” hry, “ master,” and the rest of the name *wose{r), “ powerful “ | Neb hapet Ra Mentuhotep II | 11 |

| 14 | Biyres | 10 | Sehotep Ib-Ra Amenemhat I | 12 | |

| 15 | Saophis | 29 | “Money getter or trafficker” | Senusret I * | 12 |

| 16 | Saophis II | 27 | Senusret II * | 12 | |

| 17 | Moscheres/Mencheres | 31 | “Gift of the Sun” | Userkare Khendjer | 13 |

| 18 | Mosthes | 33 | Netjeri Mesut Senusret III | 12 | |

| 19 | Pammes | 5 | “leader-like” | Aa Bau Amenemhat III | 12 |

| 20 | Apappus | 100 | “The very great” | Pepi II | 6 |

| 21 | Echeskosokaras | 1 | Merenre Nemtyemsaf II | 6 | |

| 22 | Nitocris | 6 | A queen “Athena the Victorious” | Netjerikare Siptah | 6 |

| 23 | Myrtaeus | 22 | “Gift of Ammon” | 16 | |

| 24 | Uosimares | 12 | “Mighty is the sun” | 16 | |

| 25 | Sethinilus | 8 | “Having increased his power” | 16 | |

| 26 | Semphrucrates | 8 | “Heracles Harpocrates” | 16 | |

| 27 | Chuther | 7 | “bull-lord” | 16 | |

| 28 | Meures (Mieires) | 12 | “Loving the iris of the eye” | 16 | |

| 29 | Chomaephtha (Tomaephtha) | 11 | “World, loving Hephaestos” | 16 | |

| 30 | Soicunius | 60 | hochotyrannos | 16 | |

| 31 | Peteathyres | 16 | 16 | ||

| 32 | Stammenemes | 26 | 16 | ||

| 33 | Stammenemes | 23 | 16 | ||

| 34 | Sistosichermes | 55 | “Valiant Hermes or Heracles” | 16 | |

| 35 | Mares | 43 | 16 | ||

| 36 | Siphthas | 5 | “Son of Hephaestus” | 16 | |

| 37 | Phruoro or Nilus | 5 or 19 | “The Nile” | 16 | |

| 38 | Amuthartaeus | 63 | 16 | ||

| Total | |||||

Table 6. CFAH estimated dynasty dates.

| CFAH Estimated Dynasty Dates | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynasty | Start BC | End BC | Comment |

| 1 | 2191 / 2188 | 1924 | Two start dates. Dispersion 2191 or Thinis 2188. |

| 2 | 1924 | ~1738 | Ends about the time Amenemhat I usurped the throne. |

| 3 | 2029 | 1922 | Synchronized by Djoser’s famine and the famine of Uenephes/Djet |

| 4 | 1922 | 1825 | Menkaure lived ~33 years into the Great War, thus D4 technically overlapped with D5. |

| 5 | 1822 | 1682 | D5 appears to have begun with the Truce less than a year after the Crime of Thinis. |

| 6 | 1682 | 1479 | Nitocris died ~1479 |

| 7 | 1479 | 1479 | 70 days |

| 8 | 1479 | 1232 | Ends same year as SKL King #32 |

| 9 | 2190/1881 | 1781 | D9 ended with Fall of Heracleopolis to Thebes |

| 10 | 1781 | 1577 | D10 ended when Senusret III re-organized Egypt |

| 11 | 1881 | 1738 | D11 ended when Amenemhat I usurped the throne. |

| 12 | 1738 | 1526 | Death of Sobeknefrue ended D12 |

| 13 | 1729 | 1577/1491 | 153 years until Senusret III forked it into 4 branches in 1577, 82 more years until it ended with the Exodus. Manetho total of 497 y |

| 14 | 1715 | 1491 | From Joseph’s appointment until Exodus, 224 y. |

Now we will look at Manetho’s city dynasty groups in the order in which he listed them.

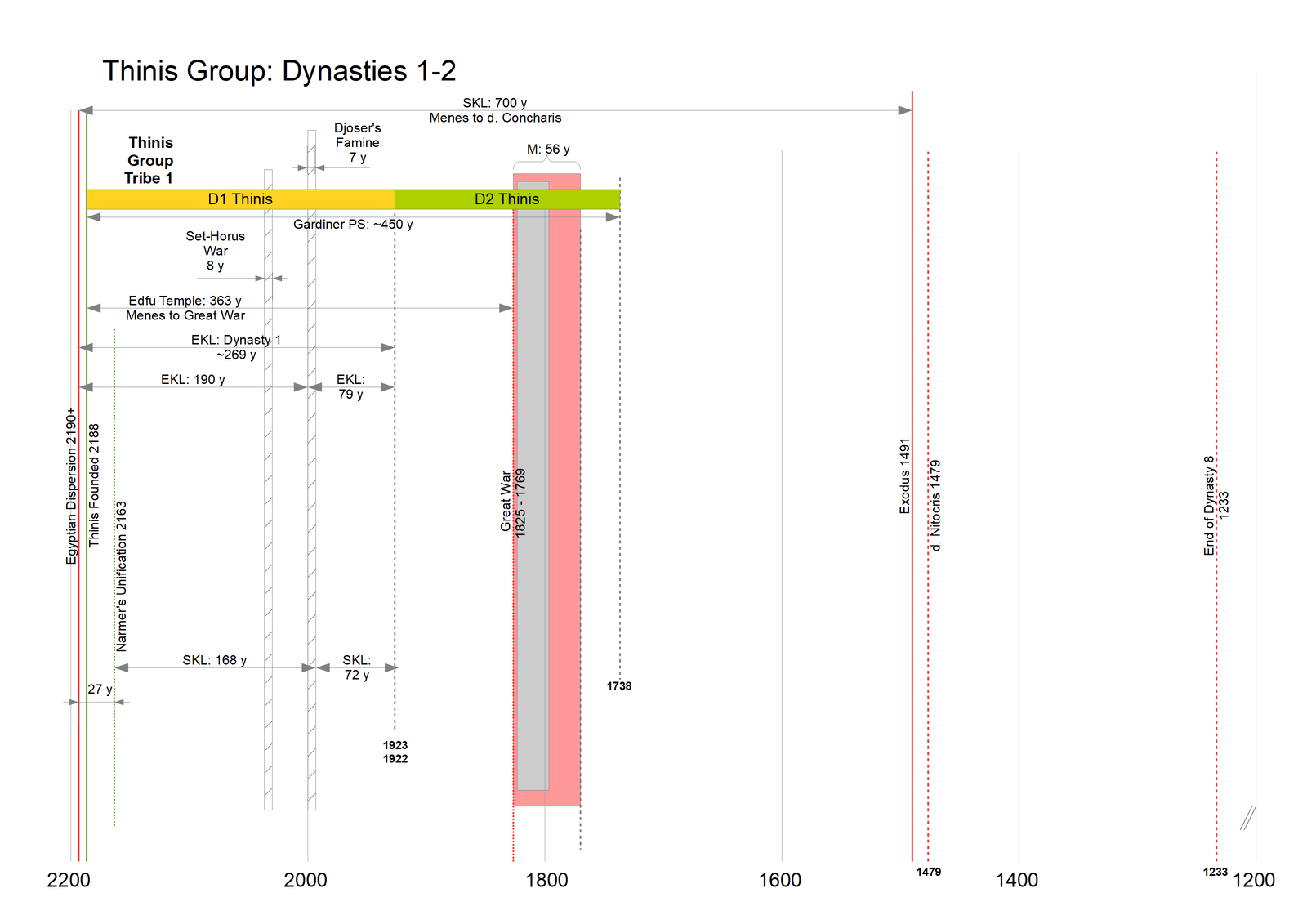

Thinis Group: Dynasties 1–2

Dynasties 1 and 2 were Kings of Thinis near Abydos where the earliest rulers of Egypt are buried (Wilkinson 1999, 3). Africanus and Eusebius give sums for Dynasty 1 that range from 254 to 270 years. Weigall estimated 264 years from the Royal Annals (1925, 9), as do we. Using our Anchor Point #2 for the founding of Thinis in 2188 BC places the transition to Dynasty 2 circa 1924 BC (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Thinis group—Dynasties 1–2.

Gardiner estimated that Dynasties 1 and 2 took up about 450 years on the Palermo Stone (1964, 67). Subtracting Weigall’s estimate for Dynasty 1, we get an approximate duration of 186 years for Dynasty 2. This suggests that the values of 297 to 302 years found in Africanus and Eusebius for Dynasty 2 include about 114 years of coreigns. Using the estimate of 186 years, Dynasty 2 would have begun around 1924 and ended within five years of 1738 BC.

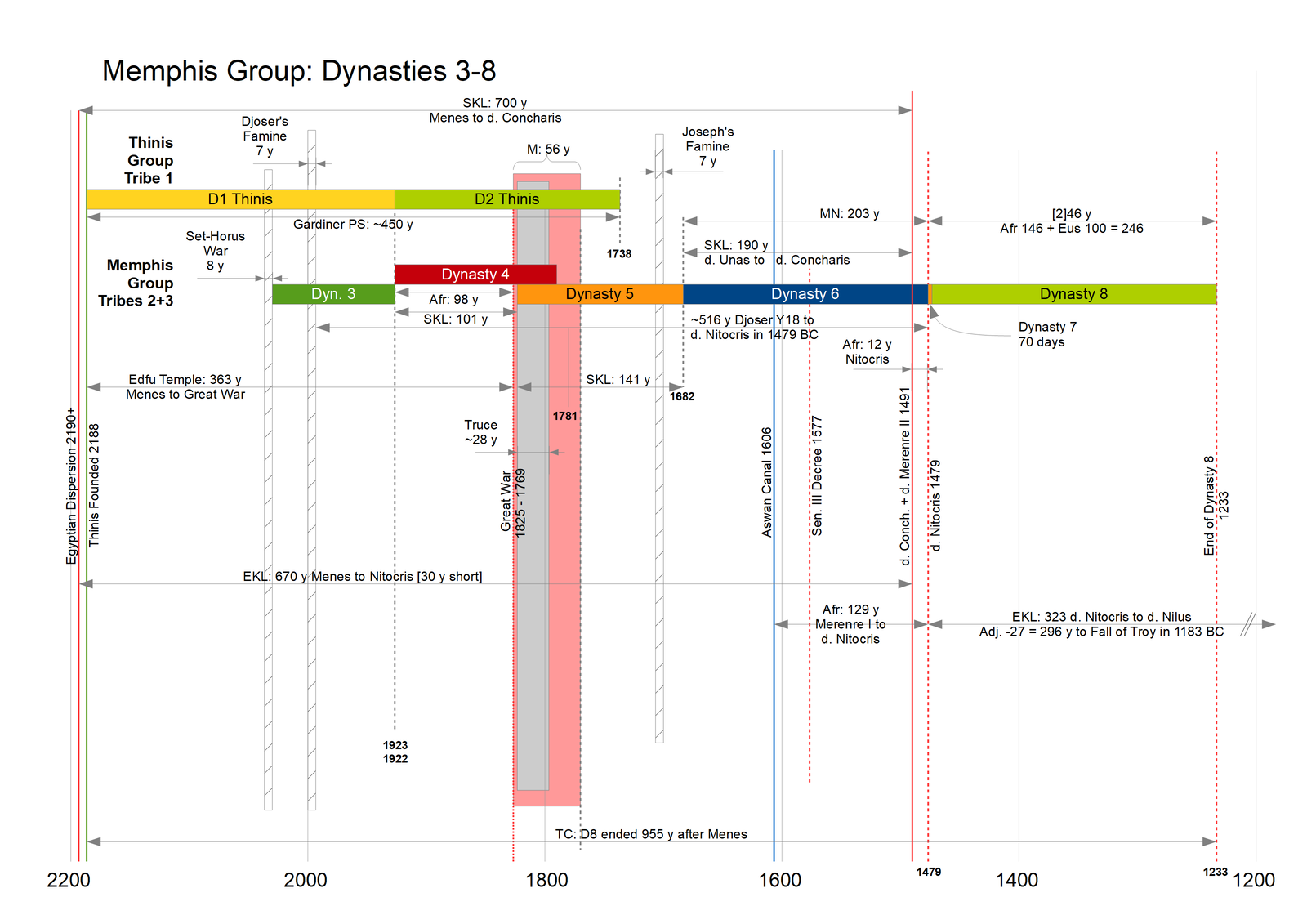

Memphis Group: Dynasties 3–8

After completing the Thinis Group we suggest that Manetho went back in time to the founding of the Third Dynasty in Memphis, which was contemporary with Uenephes (Djet) and Merneith of Dynasty 1 in Thinis, as will be shown.

Dynasties 3 to 8 present a continuous chronological sequence in the city of Memphis, except for a short period during the Great War when Dynasty 5 ruled from Elephantine as a rival faction to “The Residence” of Dynasty 4 in Memphis (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Memphis group–Dynasties 3–8.

Key Synchronisms for Dynasties 3–8

In order to accurately place the dynasties of the Memphis Group we need to establish some key synchronisms.

A. Djoser’s Famine culminated with the death of Uenephes: 2001–1994 BC

Courville argued that Kenkenes, or Ka Sekhen, of Dynasty 1 was the same person as Khasekhemwy who founded Dynasty 3 in Memphis at the culmination of an eight year rebellion by the followers of Set (Courville 1971, vol. 1, 177). It appears to us that Khasekhemwy and his son Djoser were vassals of Djet (Uenephes) and Merneith of Dynasty 1 reigning from Thinis. Articles with the name of Seth-Peribsen were found in the tomb of Merneith (Petrie 1900, plate IV.7; Wilkinson 1999, 90) as well as the tomb K1 of an official who served under Djoser (Garstang and Sethe 1903, plate X.8; Simpson 2003, 386–391), which may place them as contemporaries. However, there are known cases of items from later dynasties that were placed in the tombs of Dynasty 1 rulers when repairs were made in the Middle Kingdom (Dodson 2016, 17).

Counting down from the Unification of Egypt in the twentieth year of Menes in 2164/2163 BC (Griffith and White 2023a, Anchor Point #22) using the chronologically accurate SKL to the death of Uenephes or Djet we get:

2164/2163 BC War of Unification and Founding of Memphis; minus,

35 year reign of Menes from Memphis (SKL); minus,

63 year reign of Kuorodes (Narmer); minus,

34 year reign of Aristarchus (Djer); minus,

36 year reign of “Spanios” (Djet); gives:

1996 BC ± 2 year error for death of Djet / Uenephes / Merneith

The same famine appears to be mentioned in the Jewish tradition of Terah at the time of Abraham’s birth, which the Book of Jubilees places 530 years and the Seder Olam 500 years before the Exodus. The Famine Stela at Sahel Island records the Ptolemaic Era tradition of a seven year famine ending in the eighteenth year of Djoser (Simpson 2003, 386–391). We tentatively identify the eighteenth year of Djoser as the final year of Uenephes and Merneith of Dynasty 1, pinpointing that year as 1994 BC.

A rough confirmation of this date from the other direction can be estimated by adding the dynastic durations from the death of Nitocris in 1479 BC back to the reign of Djoser in Dynasty 3.

1479 BC death of Nitocris (CFAH-3, AP #16); plus,

203 year duration of Dynasty 6 (Manetho 1964, 53–57); plus

141 year duration of Dynasty 5 from SKL kings #14–#17 (Manetho 1964, 237); plus,

101 year duration of Dynasty 4 from SKL kings #7–#9 (Manetho 1964, 235); plus,

60 years from d. Djoser to d. Sneferu in Turin Canon (Lundstrom 2020); plus,

29 year reign of Djoser (Manetho 1964, 41); minus,

18 years to end of famine; gives:

1995 BC ± 2.5 year error end of Djoser’s Famine

Merneith is also linked to the Step Pyramid by her own tomb.

The design of the tomb (S3038) at Saqqara . . . is very remarkable for within the superstructure of a familiar mastaba format there was found hidden what is in effect a buried miniature stepped pyramid. This was entirely unexpected when it was discovered, though it is known now not to be unique; Queen [M]erneith’s tomb has the same feature though, in her case, what is clearly a more primitive form. (Rice 2004, 175)

Given that Djoser and Merneith are linked by the items bearing the name of Seth-Peribsen, both are claimed to have built the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, a model of which was found in Merneith’s tomb, and the seven-year famine ended about the same time for both, we consider this a triangulated synchronism, new Anchor Point #49, Djoser’s Famine 2001—1994 BC (fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Synchronisms between Thinis and Memphis groups.

Djoser’s reign is recorded as 29 years in Africanus, but 19 years in the Turin Canon. Likewise, the preceding king, Necherophes or Nebka, is given 19 years in the Turin Canon but 28 years by Africanus. Interpreting these differences as a 9.5 year coregency, where Africanus counted the coregency for both kings rounding up, but the Turin Canon omitted it for both kings and rounded down, this places the death of Nebka/Necherophes shortly before 2001 BC, and the start of his reign in 2029 BC, thus giving us a date for the start of Dynasty 3.

Africanus gives a total of 214 years for Dynasty 3, which includes Dynasty 4 and the ten year coregency between Nebka and Djoser. Subtracting the 98 years of the D4 kings included in Africanus D3, and the 10 years of coreign, gives 106 years for the true chronological duration of Dynasty 3, from 2029 to 1923/1922 BC. Accepting this anchor point it becomes apparent that the 79 years of “Momchieri the Memphite” in the EKL, and the 72 years of “two unnamed kings” in the SKL, both counted back from the year 1923/1922 BC to the start or end of the seven year famine. The Egyptian chroniclers appear to have used 1923/1922 BC for the end of Dynasty 3, forming new Anchor Point #50, Dynasty 3 2029–1922 BC (fig. 5).

This confirmation also supports Courville’s hypothesis that Ka Sekhen, or Ka Nekhen, was Kenkenes (whom we identify as Djer) of Dynasty 1, who moved to Memphis and changed his title, starting Dynasty 3 as Khasekhemwy (Courville 1971, 166–168). We will add to Courville’s hypothesis the supposition that Ka’s name was abbreviated as Nebka meaning “Lord Ka” in the Turin Canon (Lundström 2020) and as Necherophes the founder of Manetho’s Dynasty 3 (Manetho 1964, 41). The idea that Ka Sekhen acted as a vassal of Djet or Merneith is seen by the recently discovered Sinai inscription where his earlier title, Djer, is backed by the serekh of his predecessor, Neithhotep (Tallet and Laisney 2012, 387–388), suggesting that he ruled at the behest of Egypt’s woman-king. In Djer’s tomb were found items with the serekhs of Neithhotep and of Merneith (Porter and Moss 1937).

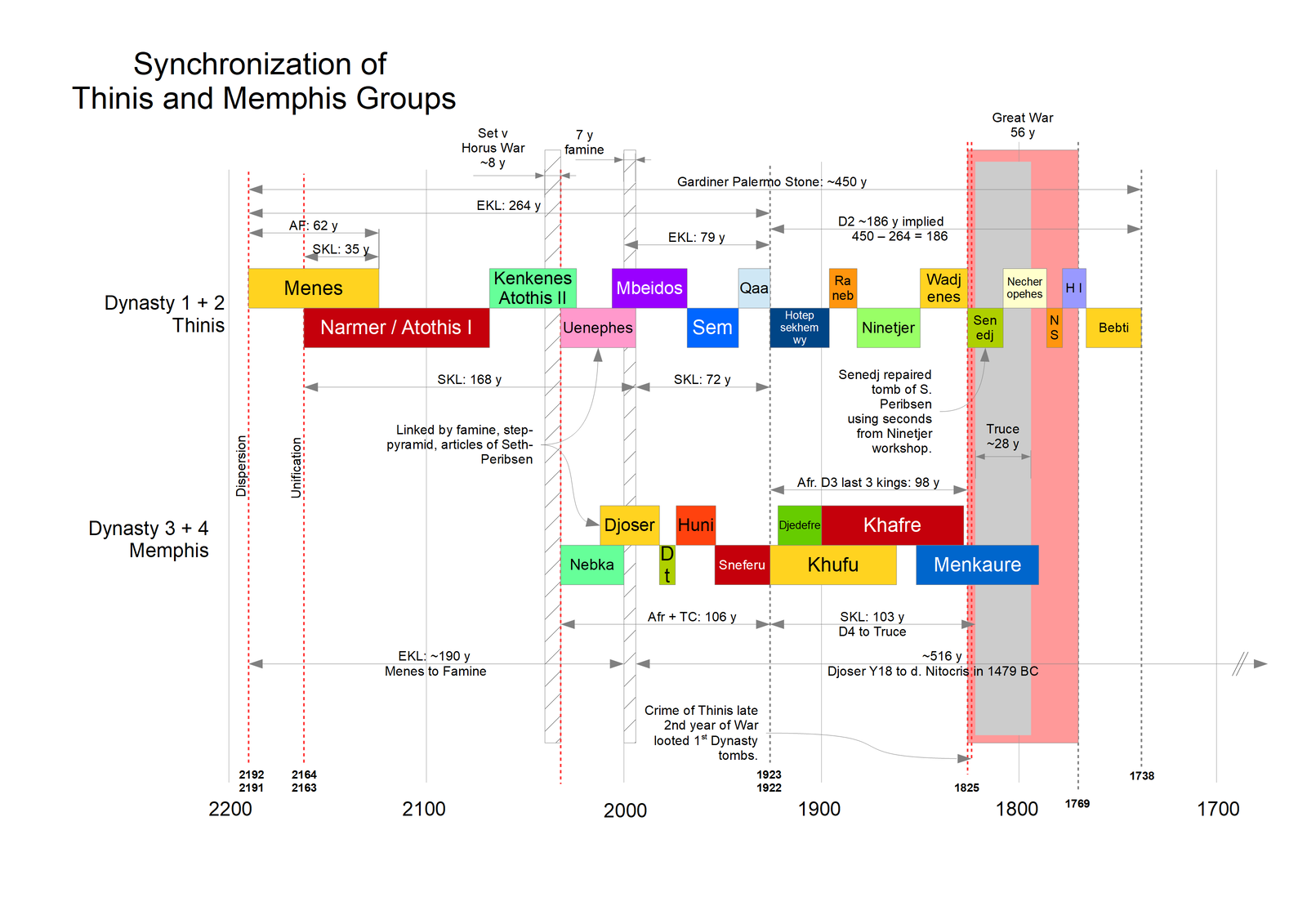

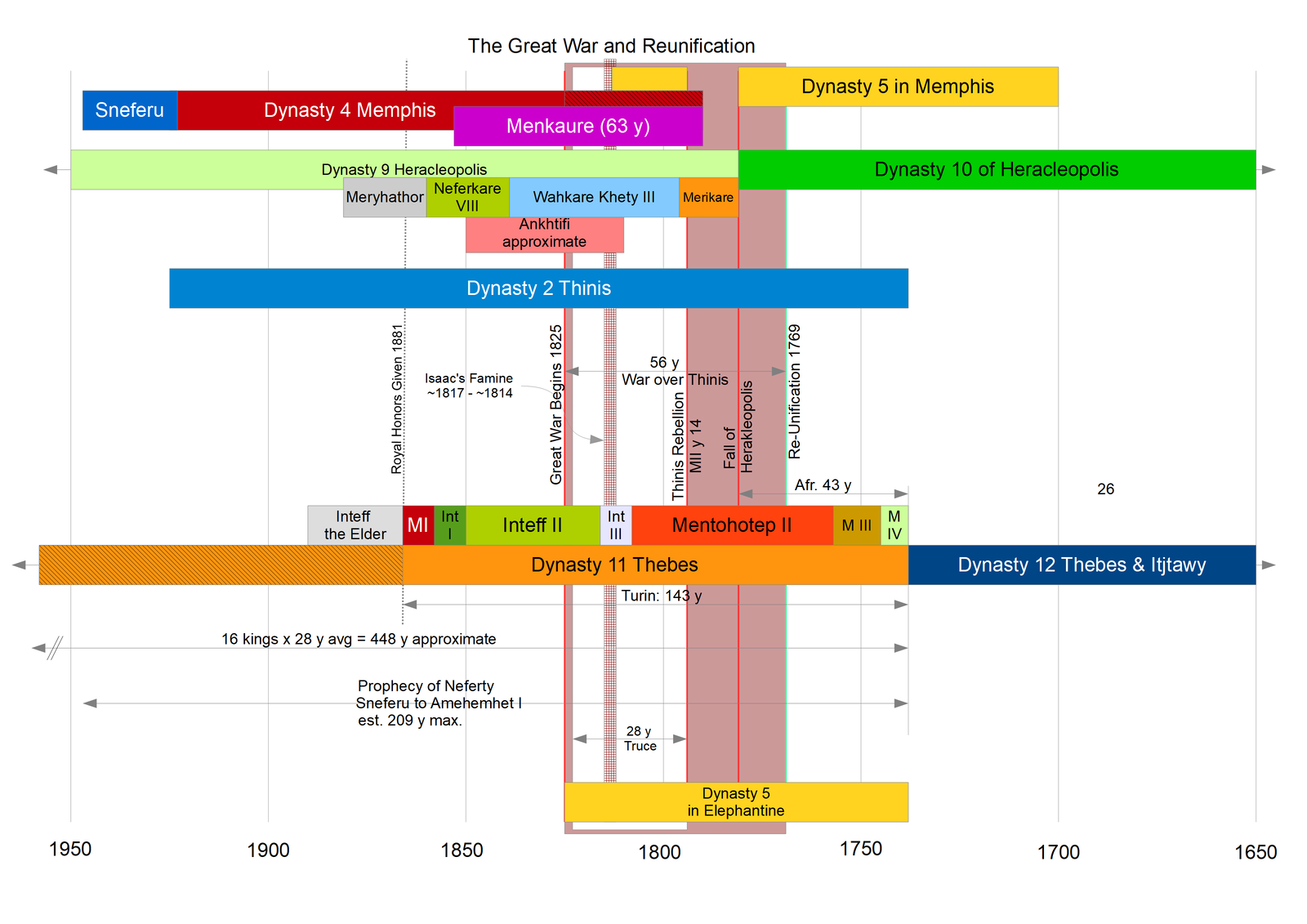

B. The Great War links Dynasties 2, 4, 5, 9, 10, and 11: 1825–1769 BC

Anchor Point #20, The Great War, starting in 1825 BC (Griffith and White 2023a), was the point where the chroniclers marked the transition from Dynasty 4 to Dynasty 5 (fig. 7). The Turin Canon gives Menkaure 28 years, while Africanus gives him 26 years as the last king of Dynasty 3, but Africanus also gives Menkaure 63 years (total reign) in Dynasty 4. Recognizing both the 26 and 28 year reigns as culminating in 1825, with a variation of two years in the start of his reign, possibly due to a coreign with Khafre, and subtracting the longer one (28 years) from his total reign of 63 years suggests that Menkaure lived 35 years into the Great War, thus dying about 1790 BC. When we look at Dynasties 9, 10, and 11 we will see they are synchronized to the Great War by an inscription in a Dendera tomb saying that the war over Thinis had lasted 56 years (Hayes 1971, 475), and a stele from year 39 of Menuthotep II celebrating reunification at the end of the war (Hayes 1971, 479).

Fig. 7. Detail view of the Great War.

A more detailed look at the Great War suggests that two years after the outbreak of the war the forces of one of the local chiefs under King Wahkare Khety of Heracleopolis, fighting on behalf of “the Residence” in Memphis, went off mission and pillaged the First Dynasty tombs of Djer and Seth-Peribsen at Abydos (Hayes 1971, 475). This was referred to as the Crime of Thinis, which outraged Egyptian society. In response, King Inteff II of Dynasty 11 of Thebes retook Thinis and then negotiated a Truce (Hayes 1971, 467) which began in the third year of the Great War, 1822 BC.

The Truce enabled two important things to occur. First, based on the Middle Kingdom repairs found in them, the kings of all five city dynasties appear to us to have collaborated to repair the damaged tombs (Bestock 2008, 42–59; Dodson 2016, 17), leading to articles from Dynasty 2 being placed in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen (Wilkinson 1999, 85), and a priest of Dynasty 4 recorded in his tomb that he had served the mortuary cults of both Seth-Peribsen and Senedj (Edwards 1971, 20). Khety of Dynasty 9 mentioned the repairs to what his men had destroyed in his Instructions to Merykare (Simpson 2003, 163).

Second, Userkaf probably used the 28 year truce to ingratiate himself with Menkaure and is thought by some to have married Khentkaus I, the supposed daughter of Menkaure and widow of Shepseskaf (Rice 1999, 96). Some Egyptologists have argued that by marrying, Userkaf and Khentkaus united the two rival branches of the royal family (Verner 1994, 119). The Truce and the marriage, which appears to have occurred in the seventh year of the Truce, enabled Userkaf to build his pyramid outside of Memphis, despite the fact that Egypt was not yet reunified. However, this alienated Heracleopolis which had fought for The Residence against Userkaf in the first phase of the war, and for their loyalty they now saw their former opponent raised to the throne.

The 28 year reign of Userkaf recorded by Manetho appears to date from the start of the Truce, and his death coincides with the Thinis Rebellion, which may have taken his life. The Truce lasted 28 years until the fourteenth year of Mentuhotep II, when Merykare of Heracleopolis stirred up a rebellion in Thinis which restarted the war (Hayes 1971, 467, 479). Heracleopolis fell to Thebes 43 years prior to the reign of Amenemhat I (Manetho 1964, 63), which was the twenty-seventh year of Mentuhotep II. The Great War continued another 12 years after the Fall of Heracleopolis as Mentuhotep subdued Cush in the South and the Eastern Delta in the North, finally celebrating Reunification in his thirty-ninth year with a commemorative stele (Hayes 1971, 479).

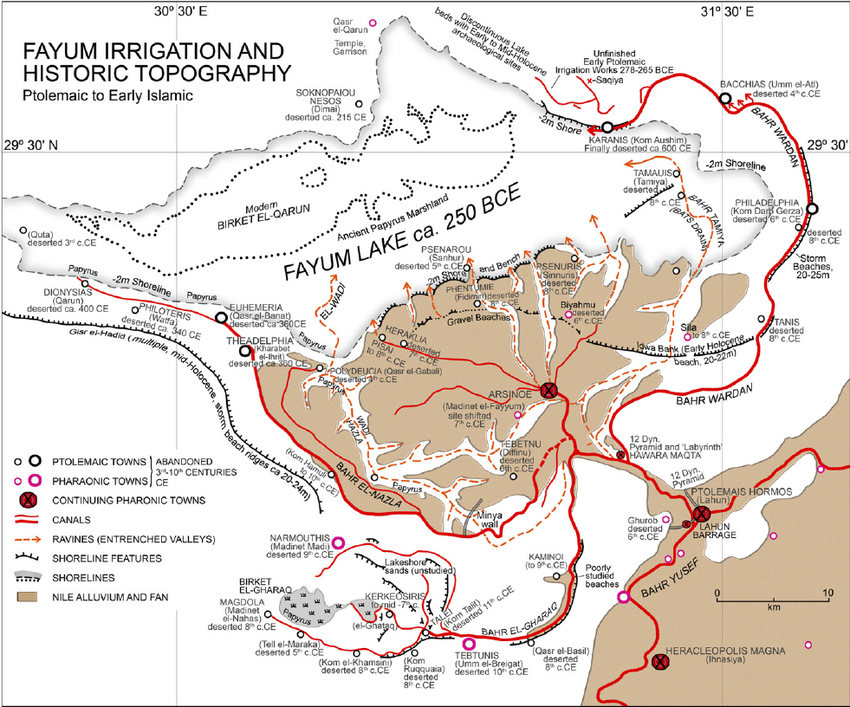

C. The Aswan Canal

An official of Merenre I of Dynasty 6 recorded that he and his men cut the Aswan Canal in what Hayes estimates was the first year of that king (Hayes 1971, 506). Senusret III also took credit for cutting the Aswan Canal in his eighth year (Hayes 1971, 507), which Hayes assumed was several centuries later. Counting back from the death of Nitocris we can estimate the date that Merenre I cut the Aswan Canal. This date will prove to be an important synchronism with Dynasty 12.

1479 BC death of Nitocris; plus,

12 year reign of Nitocris; plus,

1 year reign of Merenre II; plus,

94 year reign of Pepi II; plus,

20 year reign of Merenre I; gives:

1606 BC ±2 years error for Year 1 of Merenre I, Aswan Canal

D. The Death of Merenre II is Synchronized with the Death of Concharis of D13

Merenre II was the penultimate ruler of Dynasty 6 according to Manetho, who called him “Menthesuphis” (1964, 55). His widow, Nitocris is given a reign of 12 years by Africanus. Using Anchor Point #16 for her death, Merenre II died 12 years earlier in 1491 BC.

The Sothis King List gives 700 years from the Dispersion (Anchor Point #2) to the death of King #25, Concharis, whom Courville identified as Khaankhra Sobekhotep of Dynasty 13. The discovery of a dual-titled statue suggests that Khaankhra also used the title Khahotepra (Davies 1981, 22–23) at some point in his career, which is found as King #25 of Dynasty 13 in the Turin Canon (Lundstrom 2020) and given a reign of 4 years, 8 months, 29 days. The SKL rounds that up to 5 years for Concharis.

2191 BC Dispersion (CFAH-2, AP #2); minus,

700 years to d. Concharis; gives:

1491 BC ±6 months for death of Concharis

1479 BC death of Nitocris (CFAH-3, AP #20); plus,

12-year reign of Nitocris (Manetho 1964, 55); gives:

1491 BC ±6 months for death of Merenre II

1491 BC is the date of the Exodus in the Ussher-Jones chronology (Jones 2019, 24). During the combined events of the ten plagues and the drowning of the army in the Red Sea, somewhere between one-sixth and one-third of all Egyptian men must have died. The deaths of Concharis and Merenre II form new Anchor Point #51 in 1491 BC.

E. Dynasty 8 ended in 1233 BC, 955 years after Menes, as per the Turin Canon

In a previous paper, we noted that Dynasty 8 ended 955 years after Menes, spanning from 2188 BC to 1233 BC (Griffith and White 2023a, Anchor Point #14). This duration in the Turin Canon appears to be a true chronological duration rather than a sum of Dynasties 1–8, parts of which reigned in parallel. The first portion of the Sothis King List, Kings #1–#32 also ends in the year 1233 BC, suggesting it was chronologically significant for some reason. That was about the year that Tukulti Ninurta I conquered Babylon (Griffith and White 2023a, Anchor Point #15), which was ruled by the Semitic Amorites and Kassite tribes who were closely related to the Amalekite Hyksos who ruled Egypt at that time.

Egyptologists identify 17 kings in Dynasty 8 from the Abydos Canon (Beckerath 1999, 66–71), though we recognize two of them, Netjerkare Siptah and Neferkare Pepi Seneb as the final kings of Dynasty 6.

For Dynasty 8, Africanus gives 146 years, while Eusebius gives 100 years. Hypothesizing that these were two subdivisions of an actual period of 246 years in the original copy of Manetho, Dynasty 8 is seen to end 246 years after Nitocris died in 1479 BC. Dividing the 246 years by 15 kings gives an average reign of 16.4 years, which is on the low side, but still reasonable.

There is a total of 181 years found in column 5.14 of the Turin Canon, which is assumed by Ryholt to represent the sum of Dynasties 6 to 8 (Ryholt 2000, 94 ff, 91). However, that period is too short to contain Dynasty 6, which can be shown from Africanus, the EKL, and SKL to have lasted 203 years. It appears to us the 181 years must refer to some subset of the 246 years from the death of Nitocris to the end of Dynasty 8.

Assembling these durations and anchor points produces the estimated dates for Dynasties 3–8 found in fig. 5 and table 4, where Dynasty 3 began with Nebka in Memphis in 2029 BC, and Dynasty 8 ended circa 1233 BC.

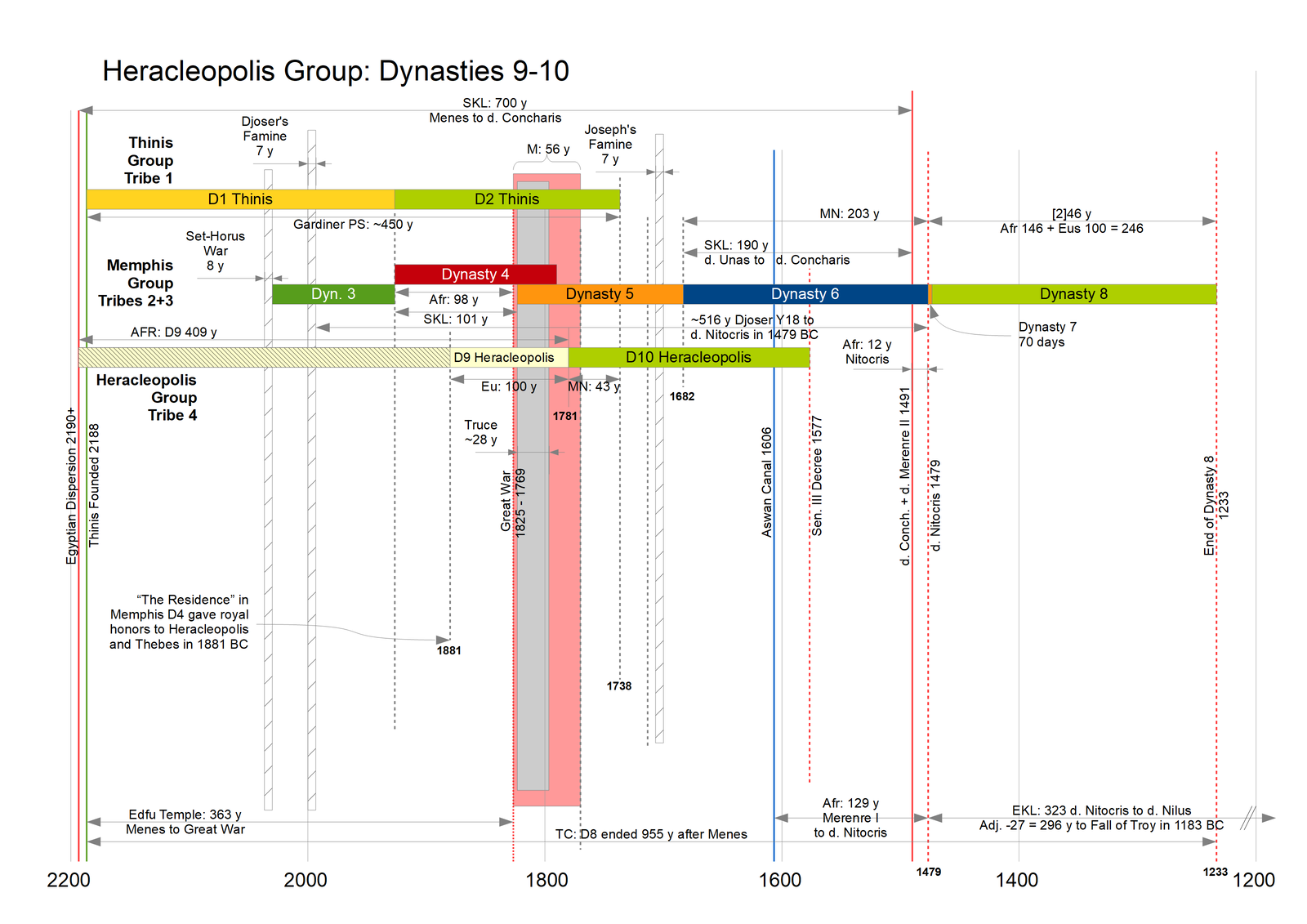

Heracleopolis Group: Dynasties 9–10

After Dynasty 8, Manetho jumps back to the beginning of Egyptian history with Dynasty 9 in Heracleopolis (fig. 8). Manetho gives 409 years for Dynasty 9, while Eusebius records 100 years for the same. Both durations can be seen to be chronologically true but are speaking of different periods.

Fig. 8. Heracleopolis group—Dynasties 9–10.

In our earlier papers we identified the year 2192/2191 BC as the date of the Dispersion (Griffith and White 2022b; 2023a). Several of the Egyptian records seem to use a start date about six months later in 2090 BC.

Counting 409 years from the Egyptian date of the Dispersion in 2190 BC gives 1781 BC for the end of Dynasty 9. If we mark the end of Dynasty 9 as the Fall of Heracleopolis to Thebes, as the evidence will suggest, then Dynasty 10 ended either 185 (Manetho 1964, 63) or 204 years (Schoene 1875, vol. 2, 214) later, giving the years 1596 and 1577 BC. In our calculations for the Thebes group, we will confirm these dates by counting back from the death of Concharis, and also provide a hypothesis for the two end dates for Dynasty 10.

Mainstream Egyptologists place Wahkare Khety and Merykare as the last two known kings of Dynasty 10 (Hayes 1971, 996), though some make Wahkare Khety the founder of Dynasty 9 (Beckerath 1999, 74). However, we place Khety and Merykare at the end of Dynasty 9 for reasons that will become clear below. The death of Merykare is recognized to have been a few months before the fall of Heracleopolis to Mentuhotep II (Hayes 1971, 467), which we argue ended Dynasty 9, not 10.

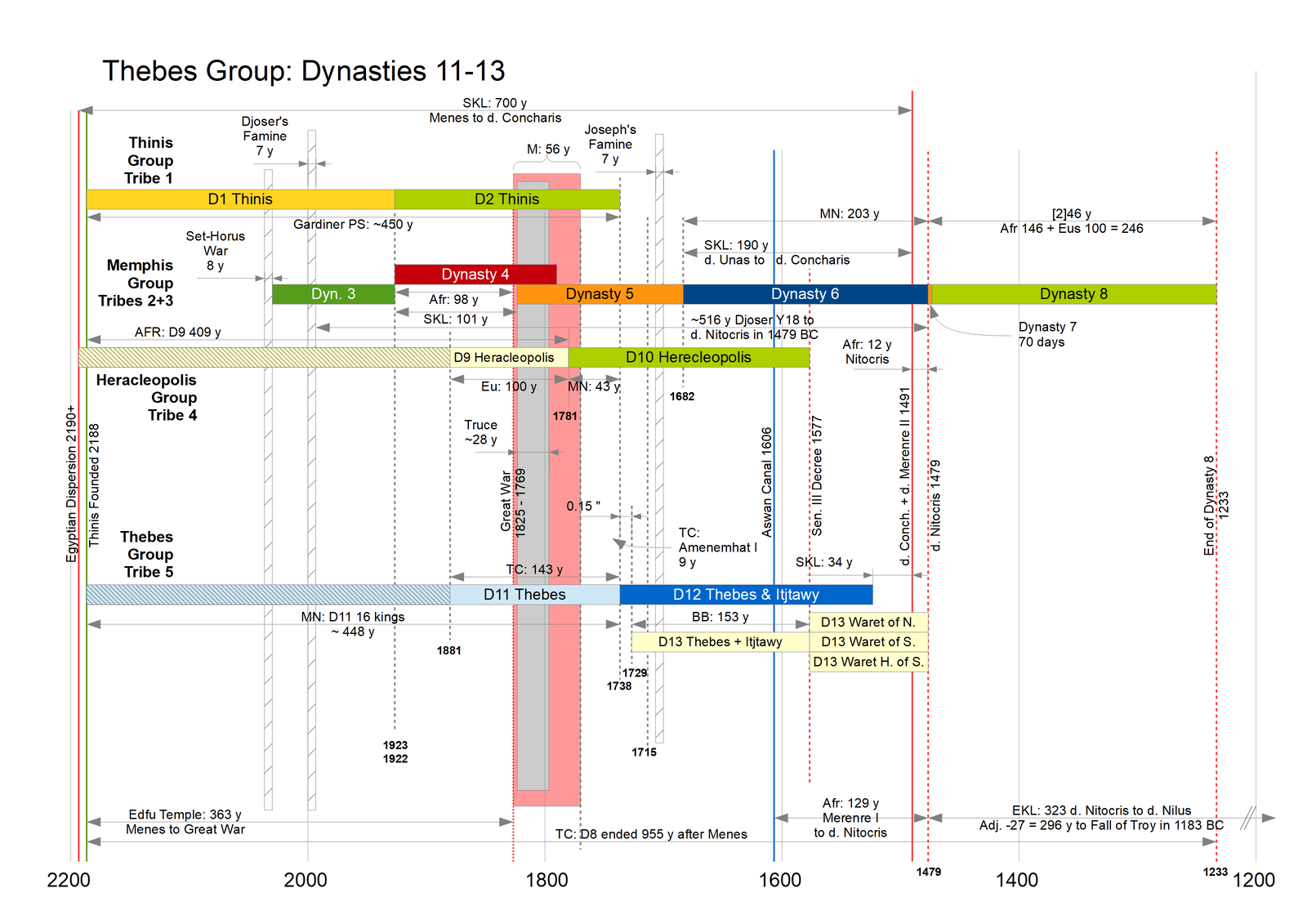

Thebes/Itjtawy Group: Dynasties 11–13

We suggest that with Dynasty 11 in Thebes Manetho went back to the beginning of Egyptian history (fig. 9). According to Diodorus, some of the priests of Egypt said that Thebes was founded by Egypt’s first god-king, Osiris, while others said it was founded eight generations later (Diodorus 1935, Book I.15.1–2). The Eratosthenes King List counts the kings over Thebes and begins with Dynasty 1 followed by Dynasty 3 before listing the kings of Dynasty 11. Therefore the Theban priests appear to have counted their history back to the founding of Thinis by Menes in order to reach the dawn of Egyptian history.

Fig. 9. Thebes group—Dynasties 11–13.

Dynasty 11 of Thebes—From the Dispersion to Dynasty 12

The full duration back to the start of 11 was not preserved by Manetho’s redactors. Instead, we are given 16 kings who reigned 43 years by Africanus and Eusebius (Manetho 1964, 63), 60 years by Barbarus (Schoene 1875, vol. 2, 214), and six kings who reigned 143 years in the TC (Lundström 2020). If we multiply 16 kings by the 28 year average reign for that period in the SKL, we arrive at an estimate of 448 years for the full length of Dynasty 11. Somewhat confirming this rough estimate, the EKL lists 404 years of kings prior to Biyres, whom we identify as Amenemhat I of Dynasty 12. However, the EKL omits three or four decades of Dynasty 11 in order to make up for listing both Amenemhat III (#19) as “Pammes” and Pepi II (#20) as “Apappus,” though their reigns overlapped by several decades.

While the 43 and 143 year durations may appear to be the result of dropping the “100” rho symbol from the Greek by a copyist, we see another solution. As can be calculated from the Turin Canon, the 43 years counted from the defeat of Heracleopolis by Mentuhotep II down to the accession of Amenemhat I of Dynasty 12. Adding the 100 years of Dynasty 9 preserved by Eusebius to the 43 years for Dynasty 11 gives the same duration of 143 years, suggesting an event that initiated the royal kingships of both Heracleopolis and Thebes in the same year. The 143 years in the Turin Canon counted from the year that the Residence in Memphis gave royal honors to the governors of both Heracleopolis and Thebes, allowing them to use the cartouches of kings.

Thus Manetho recorded durations for both Dynasties 9 and 11 back to the dawn of Egyptian history. However, it appears neither city was ruled by a true native king until 1881 BC. The monarchies in both cities were probably established by “The Residence” in Memphis, possibly in relation to the worship of “Re.” Within a few decades that would prove to have been a bad idea, as it resulted in civil war.

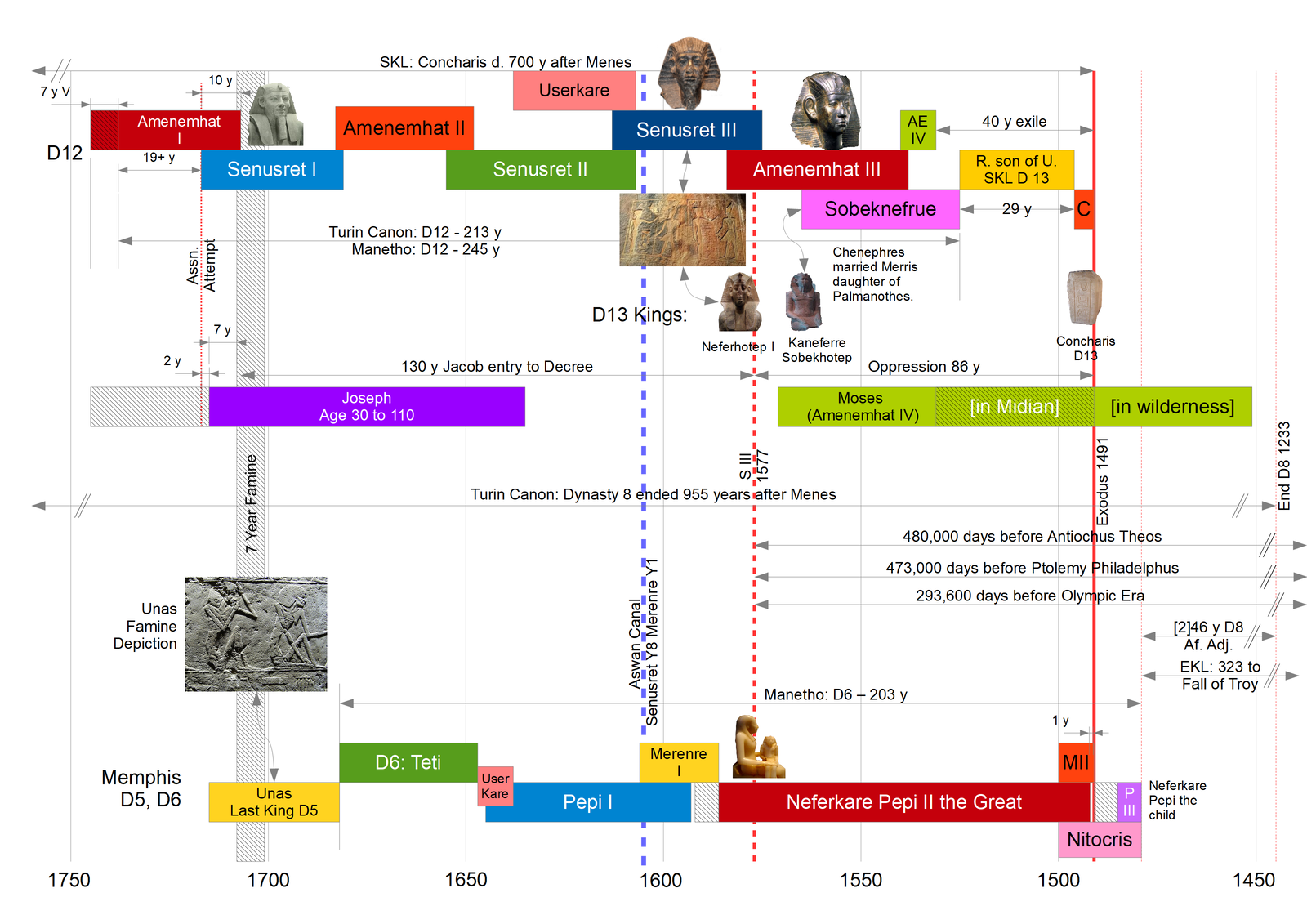

Dynasty 12

In order to pinpoint the dates of Dynasty 11, we will count forward and back from the Dispersion and from known dates in Dynasties 12 and 13. Starting with the death of Concharis in 1491 BC the SKL gives 34 years from the death of Ramesse Iubasse to the death of Concharis. Artapanus recorded that Palmanothes gave his daughter Merris in marriage to King Chenephres of Upper Egypt and that Merris was the adopted mother of Moses (Eusebius 2002, XXVII). Recognizing Palmanothes as Aa Bau Amenemhat III, Merris as Merit Ra Sobekneferu, and Chenephres as Khaneferre Sobekhotep, we have a synchronism tying Sobekneferu, the last ruler of Dynasty 12, to Khaneferre Sobekhotep of Dynasty 13. In the SKL, we recognize Ramesses Iubasse to be the Golden Horus name, “User Bau” of the same king, Khaneferre Sobekhotep, transliterated into “Iubasse.” Given that married couples often die within a short time of each other, we can use the death of Ramesses Iubasse as an approximation for the death of Sobekneferu, and thus the end of Dynasty 12, in 1525 BC, plus or minus a couple of years. Counting from the Dispersion:

2190 BC Egyptian date for Dispersion; minus,

409 years of Dynasty 9; gives:

1781 BC ±1 years, Fall of Heracleopolis, end of Dynasty 9; minus,

43 years dominance of Dynasty 11; gives:

1738 BC ±1.5 years, End of Dynasty 11, start of Dynasty 12; minus,

213 years of Dynasty 12 (Turin Canon); gives:

1525 BC ±2 years, end of Dynasty 12; minus,

34 years of Kings #24 and #25 of SKL; gives:

1491 BC ±2.5 years, Death of Concharis; plus,

700 years of SKL back to Menes; gives:

2191 BC ±3 years, Egyptian Dispersion Date

As the durations agree within their error ranges, both forward and back, we have a triangulation forming new Anchor Point #52, the End of Dynasty 12 in 1526/1525 BC.

We can confirm this estimate for the end of Dynasty 12 by comparing the three external durations we found in Griffith and White (2023a), Anchor Point #18 for 1577 BC, the year Senusret III returned from his nine year Asian campaign and established an astronomical college on the Euphrates (Diodorus 1935, Book I.56.2; Book I.31.9). To do that we will estimate the duration from the death of Senusret III to the death of Sobekneferu and see if the numbers work.

Senusret III, whose highest attested year is 39 (Baker 2008, 400), is believed to have had a 20-year coreign with his son Amenemhat III because of a dual-dated papyrus (Baker 2008, 27). We will argue for a shorter coregency below, but for the purpose of this estimate, we will use the widely accepted 20 years. The highest attested year for Amenemhat III is 46–48 (Baker 2008, 29), which also shows evidence for a short coreign with Amenemhat IV of 2 to 4 years. The Turin Canon, which doesn’t normally count coreigns, gives 9 years 4 months to Amenemhat IV, and 3 years 11 months to Sobekneferu. Assuming the 9+ years for Amenemhat IV does not include the coreign, we make the following calculation:

1525 BC ±2 years approximate death of Sobekneferu; plus,

4 years reign of Sobekneferu rounded up; plus,

9 years of Amenemhat IV, rounded down; plus,

48 years ±2 years total reign of Amenemhat III; minus,

20 years coreign of Senusret III with his son; gives:

1566 BC ±9.5 years error approximate death of Senusret III

Senusret III campaigned in Nubia from years 8 to 19 (Baker 2008, 400), sometime after which he campaigned in Asia for 9 years (Diodorus 1935, Book I.55.10).

39 year reign of Senusret III; minus, 19 years to end of Nubian Campaign; minus, 9 year Asian Campaign; gives: 11 years before his death as earliest end for Asian campaign; plus, 1566 BC approximate death of Senusret III; gives: 1577 BC as the earliest date he could have returned from Asia

Thus for this estimate, the earliest year he could have returned from his Asian campaign to reorganize Egypt would have been 1577 BC, and the latest 1567 BC. Our externally triangulated date for the founding of the Astronomical College, 1577 BC, falls within that range, showing that our method is reasonably accurate. We will fine-tune our estimate for the dates that Senusret III reigned in the Egyptian Synchronisms section, below.

The Turin Canon records the duration of Dynasty 12 as 213 years, 1 month, and 17 days. Counting back 213 years before 1525 BC gives 1738 BC for the accession of Amenemhat I, new Anchor Point #53. Counting back 43 years to the Fall of Heracleopolis gives 1781 BC, which matches our countdown from the Egyptian Dispersion to the end of Dynasty 9. Thus we have a triangulation for the Fall of Heracleopolis and the end of Dynasty 9 in the year 1781 BC, new Anchor Point #54. Counting back another 100 years to 1881 BC gives us the year that royal honors were given to the rulers of Heracleopolis and Thebes, new Anchor Point #55. The Turin Canon counts Dynasty 11 from that year, as does the 100 year duration of Dynasty 9 in Eusebius.

The Turin Canon also gives reigns for Mentuhotep II (51 years), Mentuhotep III (12 years), and a lacuna of 7 years for Mentuhotep IV. Adding these to the year 1738 when Amenemhat I usurped the throne of Thebes, the reign of Mentuhotep II began in 1808 BC, new Anchor Point #56.

Two events of the Great War are dated to the reign of Mentuhotep II. The Thinis Rebellion occurred in year 14, and the celebration of Reunification occurred in year 39 (Hayes 1971, 467, 479). Using 1808 BC for his reign places the Thinis Rebellion in 1794 BC, and Reunification in 1769 BC.

A tomb biography in Dendera stated that the war over Thinis lasted 56 years (Hayes 1971, 475). Adding 56 to the year of Reunification gives 1825 BC, which matches the date for the start of the Great War that we had calculated from the 363 year Edfu Temple duration (Fairman 1935). A second way to confirm this is to add the 28 year reign of Userkaf (Manetho 1964, 51) to the year of the Thinis Rebellion, which gives 1822 BC, the same year that the SKL begins Dynasty 5, and corresponding to the third year of the Great War when the Truce was made. Adding three years of the war before the Truce to 1822 gives 1825 again for the start of the Great War. Thus we have a triple triangulation that ties together Dynasties 2, 4, 5, 9, 10, and 11, confirming that Anchor Point #20 for the Great War was correct and giving us an end date for the Great War, which modifies Anchor Point #20, the Great War from 1825 to 1769 BC.

Looking again at Dynasty 10, using the longer 204 year duration of Barbarus from the Fall of Heracleopolis comes to 1577 BC, which matches our triangulated date for the year that Senusret III returned from Asia and reorganized Egypt. This suggests that Senusret III ended Dynasty 10 upon his return from Asia, probably replacing it with the Dynasty 13 “Waret of the South.”

Dynasty 13: 1729–1577–1479 BC

The Turin Canon introduces Dynasty 13 with an odd phrase:

Kings who [are] after the children of Dual King Sehotepibra, alive, sound, and healthy. (Lundström 2020, Turin Canon, 7.4)

No other dynasty in the Turin Canon is introduced in this manner. “Sehotep Ibre” was the throne name of Amenemhat I, founder of Dynasty 12. At first glance, it appears to mean the kings of the dynasty that came after the Twelfth Dynasty. But wouldn’t that be the dynasty that came after Sobekneferu, the last ruler of Dynasty 12? Why list these kings as those who followed after the children of Amenemhat I, the founder of Dynasty 12?

The SKL places kings #23, #24, and #25 after Amenemhat III, though all three are recognizable from the middle of Dynasty 13. The SKL also places King #20, Usimares, recognizable as Userkare Khendjer, between Senusret II and Senusret III. It appears that Dynasty 13 had a significant overlap with Dynasties 6 and 12 (figs. 10 and 11).

Fig. 10. Synchronisms between Memphis and Thebes groups.

Fig. 11. Dynasty 13 simple solution.

In the Egyptian language of the Twelfth Dynasty period, to “follow after” a king meant to serve in his administration. According to Grajetski the autobiography of Ankhu the “Keeper of the Fields” stated that “he served as a temple scribe for Khakaure (Senusret III), and that he followed the ‘king’s son’ Amenemhat III when he was still young.” (Grajetski 2006, 66) The introductory phrase in the Turin Canon, “kings who [follow] after” could very well have meant “kings who [served] the children of [Amenemhat I].”

Amenemhat I is believed to have been the vizier of Mentuhotep IV who usurped the throne and later created a new capital, Itjtawy somewhere in the north (Baker 2008, 20–21). The Prophecy of Neferti was a propaganda tale that has a prophecy given to Nebka that Egypt would fragment into pieces, but a king “Ameny” from Elephantine would reunite Egypt (Simpson 2003, 214–220). While Mentuhotep II had reunited Egypt in his thirty-ninth year, the city dynasties had begun to go their own ways again after his death. The vision of Amenemhat I was apparently to create a federal government of Egypt where the Great King ruled over the city dynasties. The problem was that his viziers were not kings and were outranked by the kings of the city dynasties, who had their own viziers. The match between Dynasties 12 and 13 gives the appearance that Amenemhat created the Dynasty 13 “King” as a cabinet position to serve as something like a vice-president, with sufficient rank that the kings of Memphis, Thebes, Heracleopolis, and Avaris, would be compelled to obey them. Both the kings of Dynasties 12 and 13 had their own viziers (Grajetzki 2009, pl. 3 [bp]; Papyrus Boulaq 18), so the Dynasty 13 position was not the vizier for Dynasty 12.

Dynasty 13 had nearly 60 kings who, even using Manetho’s 453 year duration for the dynasty, would have ruled an average of less than eight years each. Egyptologists compress Dynasty 13 down to 154 years (Ryholt 1997, 197), shortening the average reign to less than three years. It seems unlikely that a dynasty whose kings ruled an average of less than three years each could have been stable. However, Callender (2003, 159) cites Stephen Quirke as having suggested that the short reigns of Dynasty 13 are best explained by a system where men of the noble houses rotated into the position for short terms. If Dynasty 13 was created as a cabinet position of Dynasty 12, then rotating nobles through terms in that office would have been stable because the longer reigning kings of Dynasty 12 provided oversight and continuity.

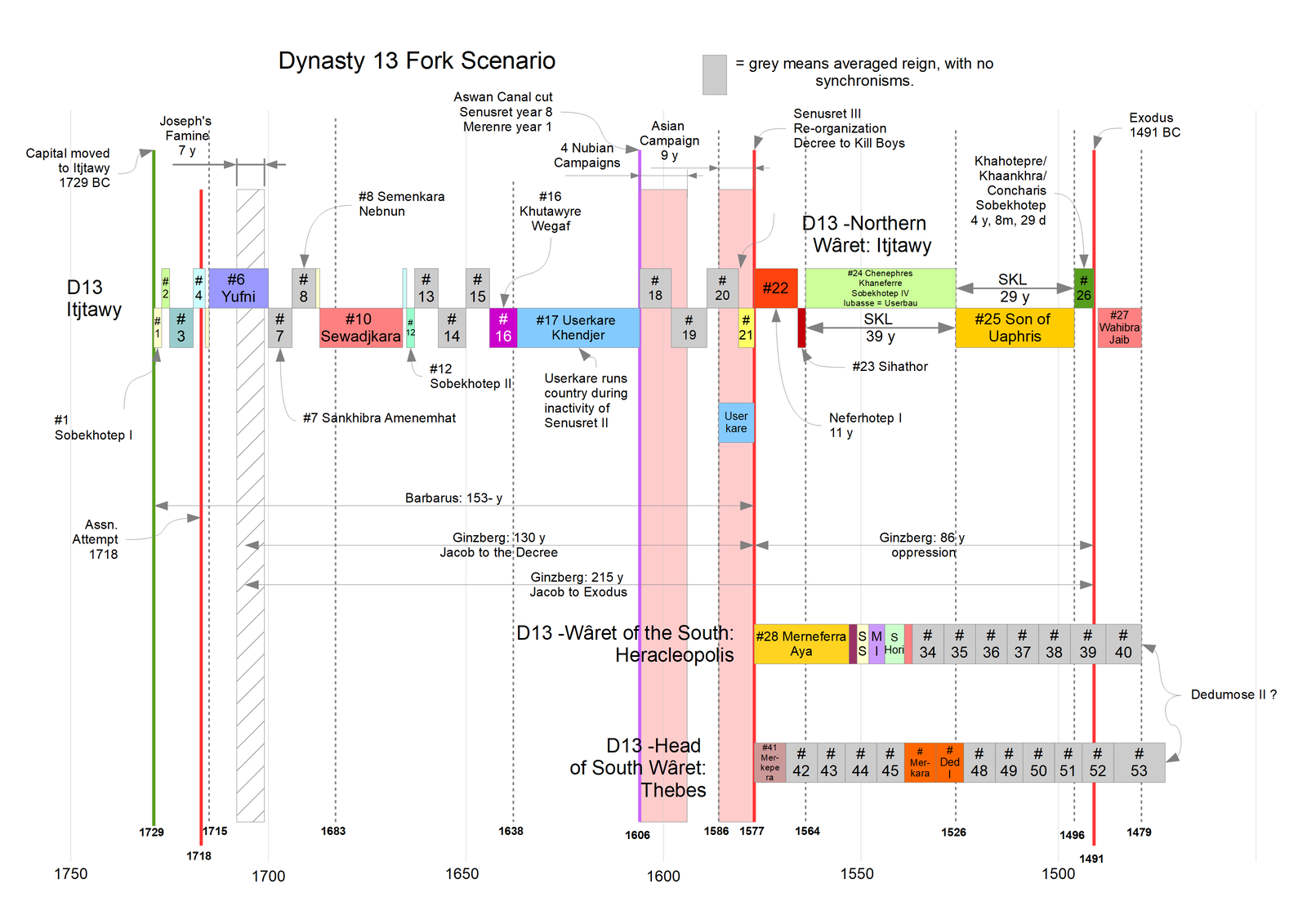

Osgood (2020, 268) proposed that Dynasty 13 began in parallel to Dynasty 12 but was later forked into three branches in different parts of Egypt at the same time. Our hypothesis is similar (fig. 12). Barbarus, whose dynastic numbers differed from Manetho’s, recorded 153 years for Dynasty 12, by which he appears to have meant Manetho’s Dynasty 13. 153 years is also quite close to Ryholt’s estimate for the length of Dynasty 13 (Ryholt 1997, 197).

Fig. 12. Dynasty 13 forked solution.

Manetho (1964, 73) gives 453 years for the total number of years for Dynasty 13. If we subtract the 153 years from that total, the remainder is 300 years. Senusret III reorganized Egypt into three administrative divisions called “warets:” The Waret of the North, The Waret of the South, and Waret of the Head of the South, each containing 12 nomes (Callender 2002, 164). These were probably located respectively in Itjtawy, Heracleopolis, and Thebes. If he did this when he reorganized Egypt in the year 1577 as we propose, then it was 98 years from his reorganization until the death of Nitocris in 1479 BC. Three branches reigning 98 years comes to 294 years, six years short of 300. Perhaps Salitis of the Hyksos killed off Nitocris and two of the branches in 1479 BC but allowed one of the branches held by Dedimose aka “Tutimaeus” (Manetho 1964, 79) to reign six more years until they could complete their takeover and reorganization of Egypt under Amalekite administration.

Counting the 153 years prior to the 1577 reorganization, Dynasty 13 would theoretically begin in 1730/1729 BC. Amenemhat I was given a reign of nine years in the Turin Canon, though his highest attested date was 30 years (Baker 2008, 22). Manetho places Amenemhat I between Dynasty 11 and 12 and gives him a reign of 16 years. He is believed to have been the vizier of Mentuhotep IV of Dynasty 11, who reigned seven years (Turin Canon). Counting seven years before the 1738 BC start of Dynasty 12, gives 1745 BC for the start of the reign of Mentuhotep IV and his vizier Amenemhat. Sixteen years from 1745 also comes to 1729 BC, thus forming a triple triangulation for 1729 BC as the year Amenemhat I moved the capital to Itjtawy and founded Dynasty 13 to serve in his cabinet. This triangulation forms new Anchor Point #57, the Founding of Itjtawy and Dynasty 13 in 1729 BC.

1525 BC death of Rameses-Iubasse & Sobekneferu; plus,

213 years of Dynasty 12 (Turin Canon); gives:

1738 BC accession of Amenemhat I; minus;

9 year TC reign of Amenemhat I; gives:

1729 BC founding of Dynasty 13, relocation of capital to Itjtawy; minus,

153 years of the main line of Dynasty 13; gives:

1576 BC ±1.5 years for Senusret III reorganization of Egypt

The reigns of the first four kings of Dynasty 13 are preserved in the Turin Canon (Lundström 2020, Turin Canon, 7.4–8.29), and total about 13 years, though an additional king with a short reign may be missing (Lundström 2020, Turin Canon, 7.6). The fifth king is Iufni (7.9), whom Courville proposed was a possible misreading of Yusef (1977), that is, Joseph. 13+ years after 1729 comes to the year 1716/1715. This falls within one year of the 1715 date for Joseph’s promotion to “a father to Pharaoh” (Genesis 45:8) in the Ussher-Jones Chronology (Ussher 2003, §132).

The reason that Barbarus records the 153 year duration may be that by splitting Dynasty 13 into the three “warets” in 1577, Senusret III effectively demoted the Dynasty 13 Kings, reducing their authority to little more than arch-nomarchs with 12 nomes each. The main run of Dynasty 13 with the full power of the Egyptian state would thus have lasted only 153 years.

Ankhu and Neferhotep connected to Senusret III and Amenemhat III

The perplexing problem of the life of Ankhu provides strong evidence that Dynasty 13 was contemporary with Dynasty 12. Quoting Grajetzki (2006, 55, 66 emphasis added):

The ‘overseer of the fields’. Ankhu, who started his career under Senusret III and seems to have lived into the Thirteenth Dynasty, will be discussed later . . .

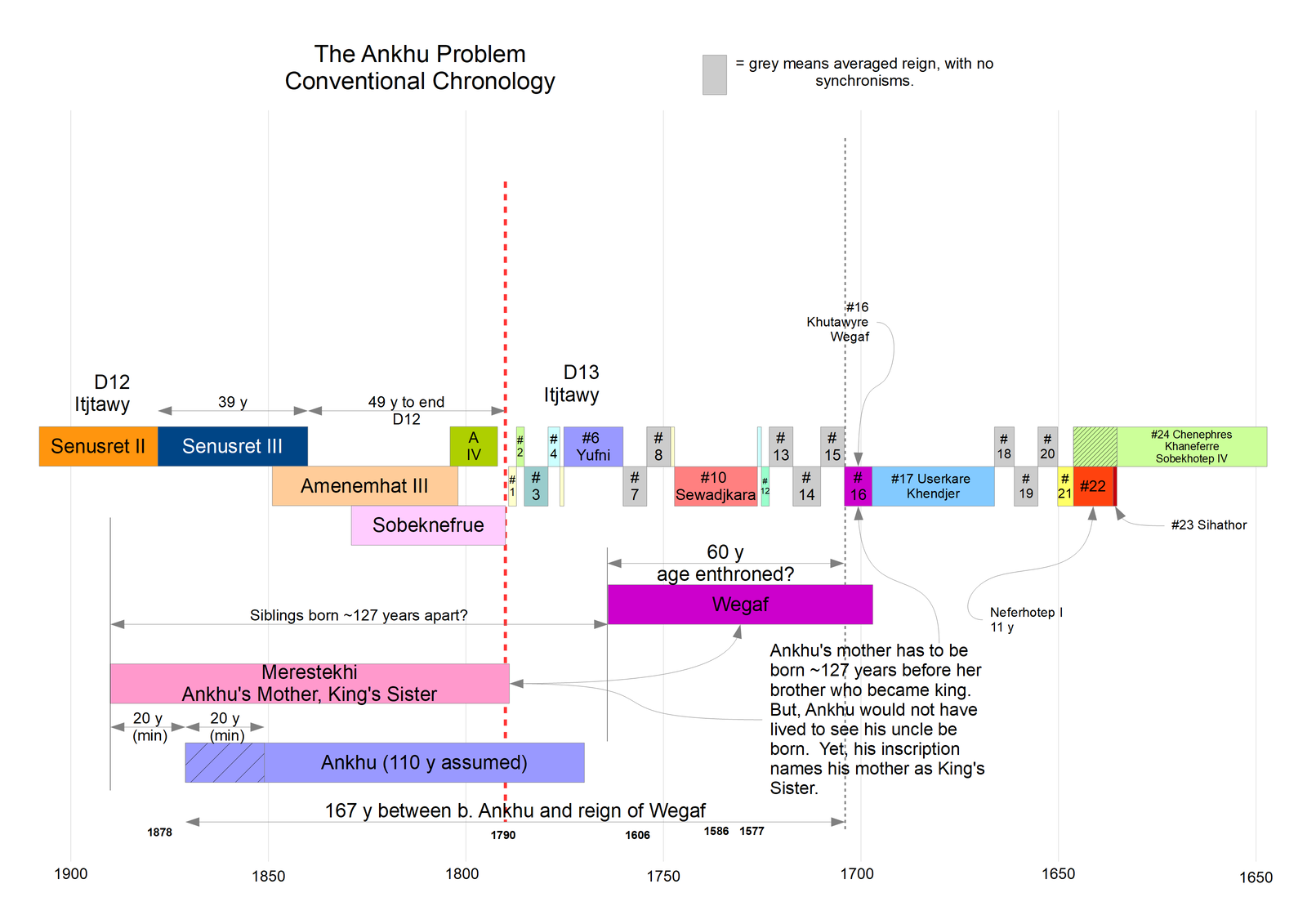

The name of the first ruler of the Thirteenth Dynasty is, then, still disputed, but it seems likely that it was a certain Khutawyre Wegaf. . . . Another group of sources perhaps related to the family of [Wegaf] are monuments of the ‘royal sealer’ and ‘overseer of fields’, Ankhu. Ankhu states in a tomb inscription that he served as temple scribe for Khakaure (Senusret III) and that he followed the ‘king’s son’, Amenemhat III, while he was still young. This must have happened during the long coregency of the two kings. The inscription dates Ankhu securely to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty. In the same inscription Ankhu is called ‘born of the king’s sister Merestekhi’. On other monuments relating to Ankhu the woman does not have this title. She seems to have been appointed at one point in her life to ‘king’s sister’, obviously when her brother, who was one of the first kings of the Thirteenth Dynasty—perhaps Wegaf himself, became king.

Based on the conventional chronology (fig. 13), Grajetzki’s dilemma is that it seems impossible that the mother of a man, Ankhu, who was an adult in reign of Senusret III could have been the sister of the King Wegaf in Dynasty 13 who reigned, at the very earliest, 89 years after the birth of his nephew. This is also the driving consideration of Ryholt’s and Grajetzki’s attempts to place Wegaf as the first king of Dynasty 13. If Wegaf could be placed as King #1 of Dynasty 13, the chronology could conceivably work, though Wegaf would still have been born 40 years after his sister, Akhu’s mother. To leave Wegaf in position #16 where the Turin Canon places him adds more than 80 years to the approximately 69 years from Anku’s birth to the end of Dynasty 12. In other words, Akhu’s mother became “king’s sister” of King Wegaf 167 years after she bore her son. That stretch defies every chronology.

Fig. 13. The Ankhu problem in conventional chronology.

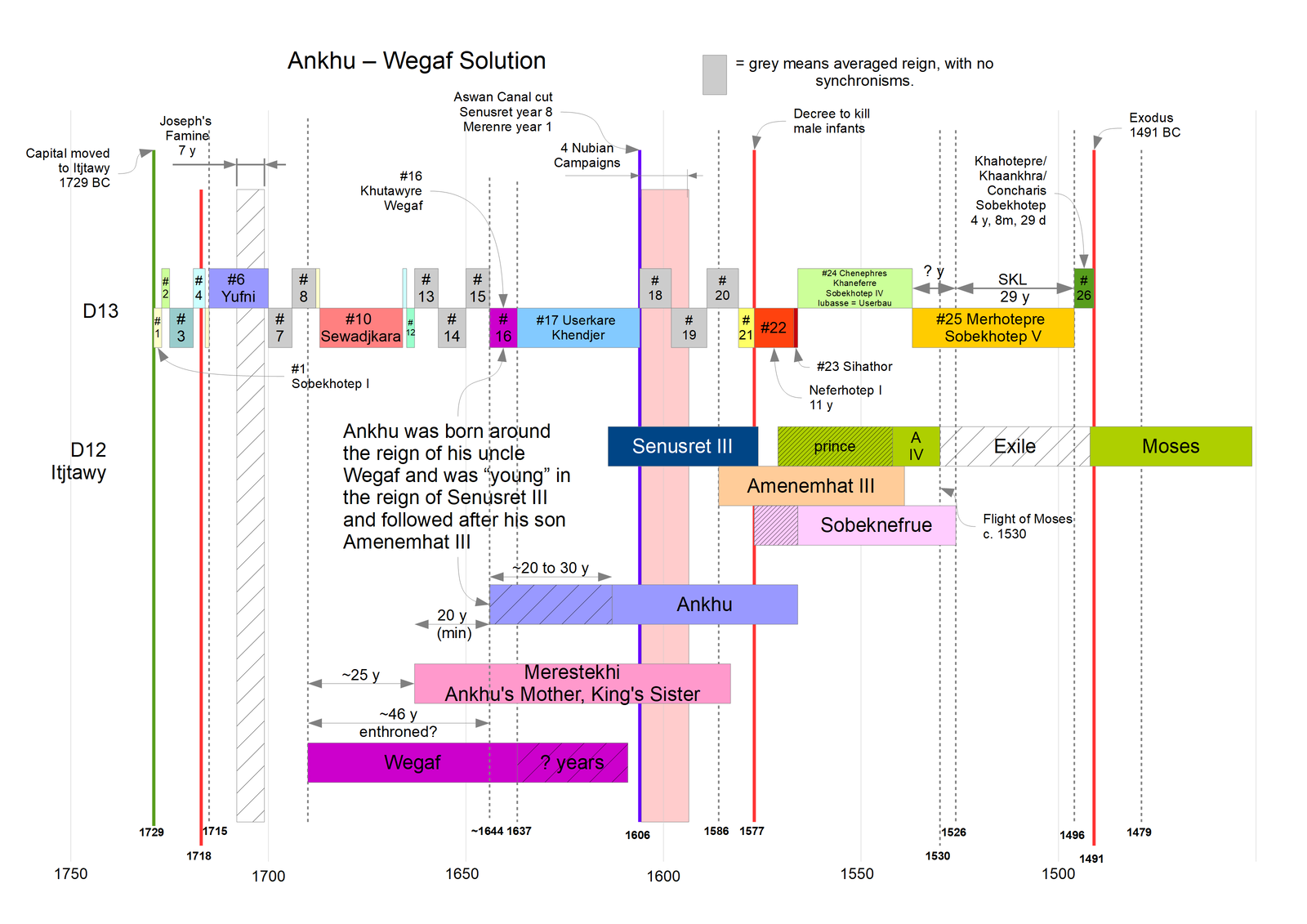

However, by placing Dynasties 12 and 13 as contemporaries, Wegaf served as the Dynasty 13 king in the cabinet of Dynasty 12 somewhere between kings #1 and #16 prior to the reign of Senusret III. While Ryholt suggests that Wegaf should be considered the first king of that dynasty, he also admitted that it appears that the prenomons of #1 and #16 were switched (Ryholt 1997, 316ff). Kitchen conclusively demonstrated that Wegaf must have been King #16, not King #1 (Kitchen 1967, 45, note 2). For Ankhu to be “young” in the reign of Senusret III, he was probably under 30 years of age, which places his birth no earlier than 1644 BC. His mother was probably the sister of one of the Dynasty 13 kings, #13 to #16. As it happens, the only other possible location for Wegaf in the Turin Canon is #16. Our alignment of Dynasties 12 and 13 neatly solves the Ankhu problem, confirming that Dynasties 12 and 13 were contemporary (fig. 14).

Fig. 14. The Ankhu solution in CFAH.

Avaris Group: Dynasties 14 and 15

Next Manetho lists kings of Dynasty 14 in Xois, by which he is currently believed to have meant Avaris (Ryholt 1997). Xois was spelled Sais, while the Saite or Sethroite Nome was the location of Avaris (Manetho 1964, 81, note 3). A copyist may easily have confused one for the other. Given that Dynasties 14 and 15 were both seated consecutively in Avaris, they form a group in Manetho’s dynastic order (fig. 15).

Fig. 15. Avaris group—Dynasties 14–15.

Dynasty 14–c. 1715–1491 BC

The Turin Canon lists 57 kings of Dynasty 14 (Lundström 2020, Turin Canon, 9.1–10.21) most of whose seals have been excavated and cataloged. The first 30 names are in good condition and it begins with Nehesy, a name that means the Cushite. In addition to those, the seals of another 12 kings suspected to be Fourteenth Dynasty have also been found, though their placement is debated. The additional Dynasty 14 rulers with uncertain placement include Yaqub Har and Yakbim, both Semitic names.

Africanus and Eusebius give 184 and Barbarus 224 years for Dynasty 14 (Manetho 1964, 75; Schoene 1875, vol. 2, 214). We see a tight fit for the 224 years from Barbarus. Two hundred and twenty-four years before the Exodus in 1491 BC was 1715 BC, the year that Joseph AKA “Yufni” was promoted to the right hand of the king. It is logical that upon receiving the prophecy of the coming famine, Senusret I may have taken steps to reorganize Egypt, placing a petty king over the land of Goshen to rule the Asiatics there and make sure they were putting away food during the years of plenty. When Jacob came to Egypt nine years later, Pharaoh Senusret I may have made him the petty king of the Delta with his seat in Avaris (Genesis 47:1–11).

One of the early kings associated with Dynasty 14 was “Yaqub Har” whose throne name was “Mer-User-Re” (Baker 2008, 503). In Hebrew Yaqub Har could mean Jacob of the Mountain or Jacob the Great. Jacob’s second name was Isra-el, meaning “God contends.” The throne name “Mer-User-Re” while having a similar sound, User-[theophoric] versus Isra-[theophoric], has a different meaning in Middle Egyptian: “Loves the Soul of Re” or “Loves the Soul of the Creator God.” While that might be a name that could fit Jacob, the only firm evidence that Yaqub Har might have been Jacob was that they had the same given name, they appear to have lived around the same time, and they both held authority over the same location, Avaris the seat of Goshen, later called the Sethroite Nome.

In Hebrew, the word Jacobite, meaning a person of Jacob’s tribe, would be written Ya’aqobi, and the plural as Ya’aqobim. Another early king of Dynasty 14 was named “Ia-ak-bi-im” or Yakbim (Ben Tor 2010, 99ff), which looks quite close to the Hebrew for “Jacobites.” This could possibly be a reference to Joseph’s brothers ruling the province of Goshen from Avaris after the death of Jacob.

It is possible that the Turin Canon begins its list of Dynasty 14 kings with the 1577 BC Decree of Senusret III. The listed kings whose reigns are preserved had an average reign of about a year and a half, with some only reigning a few months. It seems likely that Senusret III and Amenemhat III rotated trusted men through this position in a similar way to Dynasty 13. In the 86 years from the Decree to the Exodus, the 57 listed kings would have had an average reign of 18 months, which closely agrees with the recorded reigns in the Turin Canon.

By appointing the petty kings of Dynasty 14, the Pharaoh would have kept control over the Israelites, especially after they were enslaved by the decree of Senusret III in 1577. The kings of Dynasty 14 during the years of the Oppression would have been Quislings. Thus Dynasty 14 could reasonably have continued until the year of the Exodus, at which point Avaris was evacuated by the departing Israelites.

Interestingly, the 184 year duration from Africanus is exactly 40 years less than the 224 duration from Barbarus. What happened 40 years before the Exodus that might have affected Pharaoh’s administration of Avaris? Moses killed an Egyptian official and fled into exile. It is possible that the “Hebrew Quisling” administration of Avaris was ended by Pepi II in 1530 and replaced with officials from other parts of Egypt or Nubia until the Exodus in 1491 BC.

Dynasty 15—Invasion of the Amalekites

The Fifteenth Dynasty consisted of Shepherd Kings. There were six foreign kings from Phoenicia, who seized Memphis : in the Sethroite nome they founded a town, from which as a base they subdued Egypt. (Manetho 1964, 91)

The Hyksos, whom Manetho called the “Shepherd Kings” are believed to have based their operations in Avaris, which was located in the “Sethroite Nome.” Josephus quotes another passage of Manetho in more detail:

In the Saite [Sethroite] nome [Salitis] found a city very favourably situated on the east of the Bubastite branch of the Nile, and called Auaris after an ancient religious tradition. This place he rebuilt and fortified with massive walls, planting there a garrison of as many as 240,000 heavy-armed men to guard his frontier. (Manetho 1964, 81–83)

The Ipuwer Papyrus is a Nineteenth Dynasty papyrus whose origin is believed to date no earlier than the Twelfth Dynasty (Quirke 2014, 167). Several historians have pointed out that it appears to describe the plagues upon Egypt that occurred during the Exodus (Velikovsky 2009, 52–58; Stewart 2003, 252–270). The primary argument against this interpretation is that the text describes the invasion of Asiatics rather than their departure (Enmarch 2011, 174). However, the Amalekites encountered by the Israelites after crossing the Red Sea were said by Jewish tradition to have conquered Egypt and taken the lists of Israelite slaves from the Egyptian records (Ginzberg 2001, vol. 3, 27). The Egyptians viewed the Abrahamic tribes as shepherds (Genesis 46:32–34), therefore in the Exodus year from their viewpoint the Israelites were one group of shepherds who departed Egypt, and were replaced by another tribe of shepherds, the Amalekites, who swept in as quoted by Josephus above.

Josephus quoted Manetho as saying that Salitis, the first Hyksos king, found Avaris as an existing city and rebuilt it (Manetho 1964, 81). Thus the primary objection against the Ipuwer Papyrus describing the Exodus is overcome by the fact that the Egyptian data shows the Amalekite Hyksos conquered Egypt shortly after the Israelites had departed.

To the Egyptian mind, the Hyksos were Abrahamic tribes. Thus, the Edomites and Amalekites were enemy Hyskos. But the Israelites were also viewed as being Hyksos, at least by the later Egyptians of the Ptolemaic Era who wrote these histories. This accounts for the evidence that the Hyksos had peacefully integrated in the Delta for about two centuries (Bietak 2006, 285; Mourad 2015, 130) prior to the start of Dynasty 15. The period of peaceful integration would have been the sojourn of the Israelites in Egypt for the 215 years prior to the Exodus.

The Pentateuch claims that Moses composed it during the Wilderness Wandering of Israel (Exodus 17:14; Deuteronomy 31:24), which would have ended 40 years after the Exodus, in 1451 BC. During that period the Israelites were encamped adjacent to the territory of Edom (Numbers 20). Two of the final three kings of the Edomites listed in Genesis 36:37–39 appear to match the first two of the Amalekite Hyksos kings of Dynasty 15 (Manetho 1964, 91). (Table 7) Amalek was a subtribe of Edom (Genesis 36:12). If Dynasty 15 conquered Egypt in 1491/1490, then Salitis and Bnon would have been known to Moses during the 40 years in the wilderness, especially considering that the Hyksos still claimed Edom as their homeland. The Hyksos kings in Egypt continued to use the Egyptian title, heqau khasut, “Ruler of Foreign Lands, ” (Bourriau 2002, 174–175) implying they also continued to rule their home territory, which was the foreign land referred to in the title.

Table 7. Hyksos kings named in Genesis.

| Hyksos Kings of Genesis 36 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynasty 15 Name | Genesis 36 Name | Source | Comment |

| Salitis | Saul of Rehoboth | Genesis 36:37 | Conquered Egypt |

| Bnon | Baal Hanaan | Genesis 36:38 | |

The Amalekite Dynasty 15 continued through the entire Second Intermediate Period (or Hyksos Intermediate Period) which we view as the biblical era of the Judges. Thus fixing the end date for that Dynasty is beyond the scope of this paper and will be handled in the next paper of the CFAH series.

Summary of the Interlocking Durations Argument

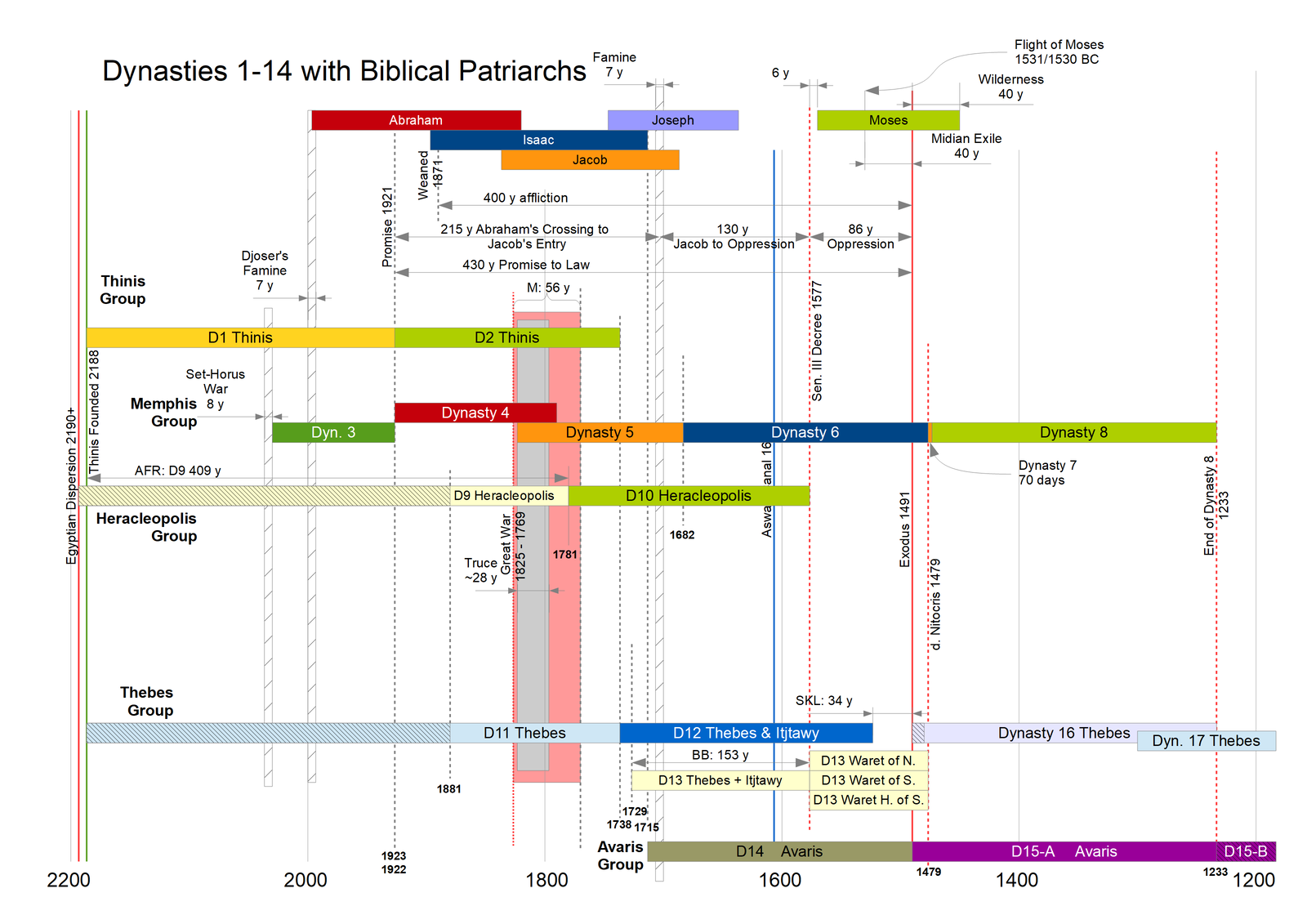

In review, the durations from the chroniclers for Dynasties 2, 9–12, and 4–5 dovetail precisely with the Great War, and also agree within three years for the date of the Dispersion. It also appears that Dynasty 2 was replaced about the same time that Amenemhat I established Dynasty 12, and about 160 years later Dynasty 10 may have been replaced by the Dynasty 13 “Waret of the South” when Senusret III reorganized the government of Egypt. Fig. 3 charts the interlocking durations cited above. In the diction of accountants, “the numbers foot.” The multiple interlocking synchronisms also create redundancy which allows event dates to be derived by several different paths. Merely plucking out one duration by disqualifying it is insufficient to disprove the entire matrix. Fig. 16 shows the Egyptian dynasties alongside the biblical patriarchs.

Fig. 16. Dynasties 1–14 with the patriarchs.

Argument 3. Synchronisms Between Egyptian Dynasties

If, as we and others have proposed, the Old and Middle Kingdoms were contemporary rather than sequential, then many synchronisms should be found between the dynasties so categorized. Fourteen such synchronisms follow.

The Dispersion—Anchor Point #2

Dynasties 1 and 9 are shown to count their origin back to either the Dispersion circa 2191 BC or the founding of Thinis 3 years later in 2188 BC. The “16 kings” of Dynasty 11, the earlier of whom were just governors, multiplied by the 28-year average reign from the SKL, go back 448 years before 1738 to about 2189 BC, thus falling within a few years of the Thinis founding date. In addition to those three cities, Courville argued that Memphis was founded only 28 years after the Dispersion after the War of Unification by Menes (Courville 1971, 181–182).

Famine of Djoser and Uenephes

As argued above, the first seven year famine synchronizes the famines of Dynasties 1 and 3 with the famine of Terah from Jewish tradition (Charles 1913, 11.13), during which Abraham was born. In the previous paper, CFAH #5 (Griffith and White 2023c), we found durations that triangulated the reign of Ninyas or Gilgamesh from 2006 to 1968 BC, as well as showing that he had a 12 year coreign with his mother, Ishtar/Semiramis I, who died in 1994 BC (Anchor Point #47). The Epic of Gilgamesh says that Ishtar sent a seven-year famine; and Gilgamesh’s famine can be seen to have ended in 1994 BC; therefore, it appears to be the same seven-year famine as that of Djoser. Djoser’s famine is seen to be a major synchronism that unites the chronologies of Sumer, Thinis, Memphis, and Abraham.

The Great War: 1825–1769 BC

The Great War synchronizes Dynasties 2, 4, 5, 9, 10, and 11 (fig. 17). Khety three times mentions “the Residence” [of Dynasty 4 in Memphis] as a higher authority in his Instructions to [his son] Merykare (Simpson 2003, 158, 159, 162).

Fig. 17. Bigger picture of the Great War.

Fall of Heracleopolis

While a dated monument for the Fall of Heracleopolis has not been found, it had to have occurred between the Thinis Rebellion and Reunification, which occurred in the fourteenth and thirty-ninth years of Mentuhotep II. We can triangulate the fall of Heracleopolis from five durations. Dynasty 9 lasted 409 years from the Dispersion, which Egyptian sources appear to have counted as 2190 BC.

2190 BC Dispersion; minus,

409 years of Dynasty 9; gives:

1781 BC ±6 months, Fall of Heracleopolis

Using the data in the Turin Canon, the twenty-seventh year of Mentuhotep, 1781 BC, was 43 years before the end of Dynasty 11. That year falls in the range between years 14 and 39, and therefore was most likely the year Heracleopolis was sacked. This date also triangulates with Eusebius’s 100 year duration for Dynasty 9.

Neferirkare Kakai Found in Both Dynasty 2 and Dynasty 5 Simultaneously

The third king of Dynasty 5 was named Neferirkare Kakai. He is found in both Dynasty 2 and Dynasty 5 under the Greek transliteration of his name, Nephercheres (Manetho 1964, 37, 51). In the CFAH model, both “Nephercheres” reigned at the same time, because they were one person holding office in two cities: Thinis and Elephantine. We hypothesize that his older brother, Userkaf, after marrying Khentkaus and moving to Memphis, installed his triplet brothers, Sahure as king of Elephantine, and Neferirkare in Thinis. When Sahure unexpectedly died, Userkaf installed Neferirkare in Elephantine as well. Thus Neferirkare is listed as Nephercheres in both Dynasties 2 and 5.

Unas Famine matches Senusret I Famine

Unas, the last king of Dynasty 5 depicted starving Asiatics on his pyramid causeway (Baker 2008, 483). Given the 203 year duration of Dynasty 6 prior to the death of Nitocris in 1479 BC, the 33 year reign of Unas would have been from 1715 to 1682 BC, entirely overlapping with Joseph’s Famine, which was 1708 to 1701 BC in the Jones chronology (Jones 2019, 56A). A multiyear famine was recorded in the reign of Senusret I (Stewart 2003, 130–131). The Nile Famine Tablet of an official named Mentuhotep, U.C. 14333, mentions an extreme low flood of the Nile in year 25 of an unnamed king. Rudd (2019) cites Simpson (2001) to the effect that several scholars place it in the reign of Senusret I, while Goedicke (1962, 25) who translated the tablet, assigned it to Dynasty 11.

The sources seem to use two different start dates for the reign of Senusret I, with the Turin Canon starting his reign after 9 years of the reign of Amenemhat I, which would be 1729 BC, the same year the capital was moved to Itjtawy, suggesting Senusret I may have served as a king of Upper Egypt starting the year that his father had moved the capital to the North. He would not have been elevated to coregent as the Great King of Dynasty 12 until after the assassination attempt in the twentieth year of Amenemhat, 11 years later (Stewart 2003, 77–78). The record low Nile 25 years after 1729 BC comes to 1704 BC, the midpoint of Joseph’s Famine in the Ussher-Jones Chronology, thus forming another triangulation and Anchor Point #58—Joseph’s Famine from 1708 to 1701 BC.

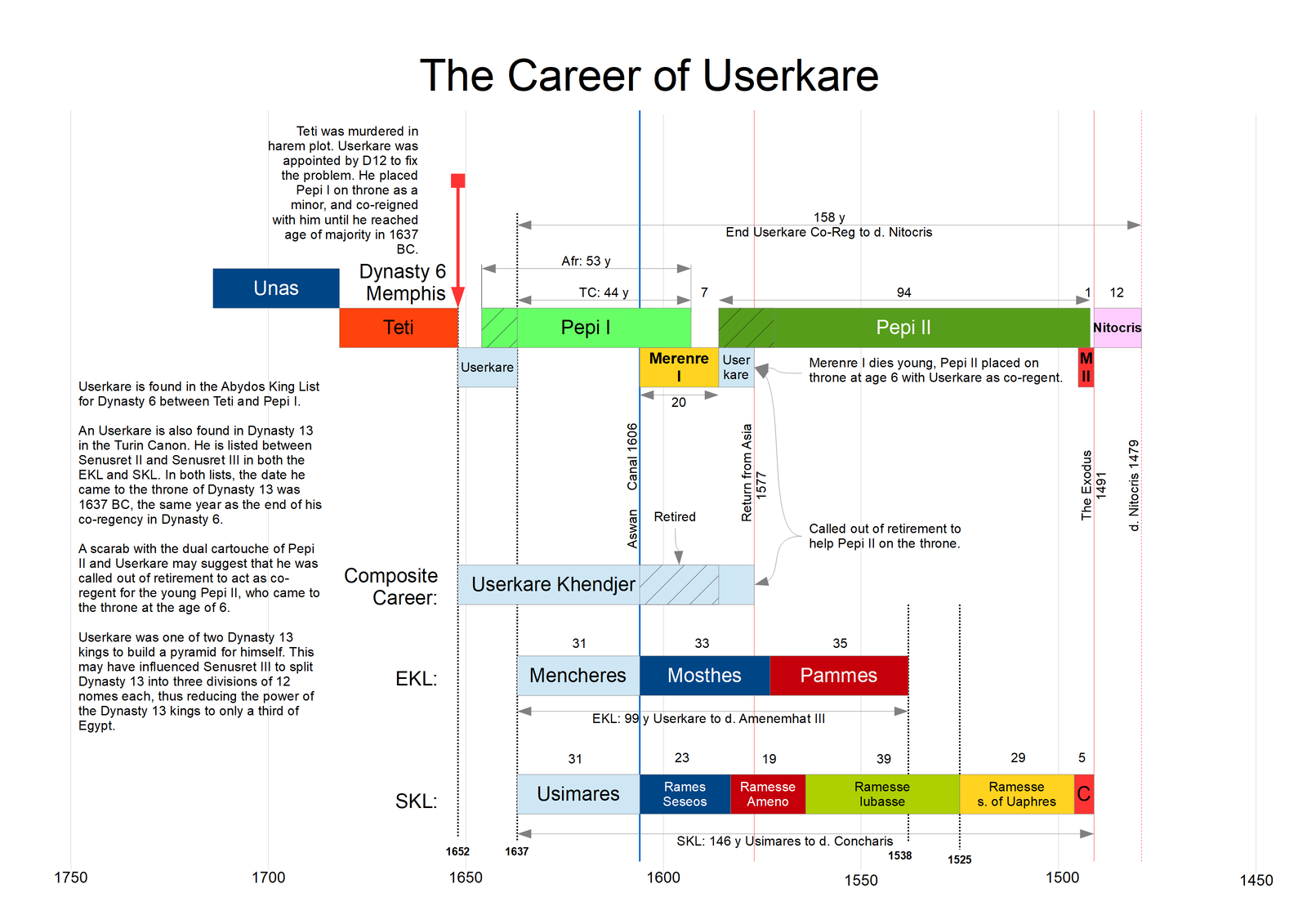

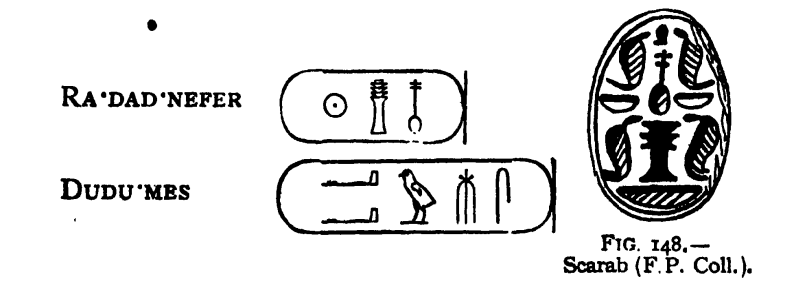

Userkare goes from D6 to D12/13 and back to D6

Another important king of Dynasty 13 was Userkare Khendjer, who is listed in both the SKL and EKL as reigning 31 years between Senusret II and Senusret III (Manetho 1964, 219, 237) (fig. 18). Another Userkare is known from the Abydos King List as king #35 listed between Teti and Pepi I (Lundström 2020, abydos-canon). When placing the dynasties as the durations and synchronisms here suggest, it becomes apparent that Userkare served as a regent for Pepi I in Dynasty 6 after the murder of Teti (Grimal 1992, 81) until the he was promoted by Senusret II of Dynasty 12 to the Dynasty 13 cabinet position as Userkare Khendjer. Manetho gives Pepi a reign of 53 years, while the Turin Canon gives him a reign of only 44 years. Interpreting the difference as a nine year coregency under Userkare when Pepi I was a minor, we can calculate the date the coregency ended.

Fig. 18. The career of Userkare.

Counting back from the death of Nitocris in 1479 BC:

1479 BC death of Nitocris; plus,

12 years Nitocris; plus,

1 year Merenre II; plus,

94 years Pepi II; plus,

7 year sole reign of Merenre I; plus,

44 year reign of Pepi I; gives:

1637 BC ±2 years, start of Pepi I sole reign, end of Userkare coregency

Counting back from the death of Chenephres (Ramesses Iubasse) in the SKL from 1525 BC:

1525 BC death of Rameses Iubasse (Khaneferre Sobekhotep); plus,

39 year reign Rameses Iubasse; plus,

19 year reign Ramesse-Ameno (Amenemhat III); plus,

23 year reign Rames-Seseos (Senusret III); gives:

1606 BC ±1.5 year error, approximate end of Usimare’s reign (Userkare); plus,

31 year reign of Usimares; gives:

1637 BC ±2 year error, approx. start of Userkare’s reign in D13

A reasonable interpretation is that Userkare appears in Dynasty 6 between Teti and Pepi I as the coregent for Pepi as a minor, until the year 1638/1637 when Pepi I reached the age of 20. Userkare was then promoted to the Dynasty 13 position, where he served Senusret II for 31 years, including the coregency with Senusret III, ending just before the first Nubian campaign in 1606. Userkare even built a pyramid for himself, one of only two Dynasty 13 kings known to have done so. Userkare’s pride may have influenced the young Senusret III to plan to reduce the power of the Dynasty 13 position, which he did in the year 1577 BC when he broke the dynasty into the three Warets, thus reducing Dynasty 13 kingship to control of only one-third of Egypt.

A scarab was found with the double cartouche of Dynasty 13 king Userkare side by side with the cartouche for Neferkare Pepi II (Hayes 1953, 342–343). Pepi II came to the throne as a child, not unlike his grandfather, Pepi I. This scarab suggests that Userkare may have been called out of retirement to help young Pepi II on the throne just as he had helped his grandfather. In all three of his positions he appears to have served as a coregent for a young king, suggesting that Dynasty 12 used him for that purpose. Given that the biblical patriarchs were still living to more than 130 years of age during the sojourn (Exodus 6:18, 20), a 75 year career for Userkaf from 1652 to 1577 was feasible.

The Aswan Canal of Senusret III and Merenre I

In order to more efficiently transport men, weapons, and supplies upstream of Aswan into Nubia, both Merenre I and Senusret III recorded cutting a canal at the First Cataract in Aswan. Hayes comments (1971, 506–507, emphasis added):