The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

Currently, there is a textual debate in creationist circles regarding whether the Masoretic Text (MT) or Septuagint (LXX) preserves the correct chronology in the genealogies of Genesis 5 and 11. Textual criticism gives us the tools to analyze all extant variants to conclude which is most likely original. Critically, the Samaritan Pentateuch gives a third textual tradition that helps reconstruct the textual history of the Genesis 5 and 11 genealogies. This paper will conclude that MT Genesis 5 and 11 is superior to LXX and SP Genesis 5 and 11 from a textual standpoint.

Keywords: text criticism; Masoretic Text; Septuagint; Samaritan Pentateuch; Genesis 5; Genesis 11

Introduction

Biblical creationists believe that God inspired Genesis as an accurate history of the world’s creation and the first ~2,300 years of world history. Much of the timeline for this period of history is based on the genealogies listed in Genesis chapters 5 and 11.

There are three main texts of Genesis that give three distinct timelines. First, the Masoretic Text (MT) has been the preferred text across many traditions. While the traditions of the Masoretes regarding the copying of the Old Testament (OT) to guarantee accuracy only began in the 500s, and the earliest complete copies come from the 900s–1000s, there is evidence that Jewish religious leaders took measures to ensure the accuracy of the text at a much earlier stage. For instance, the text of Isaiah in the Great Isaiah Scroll found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, dating ca. 125 BC (The Israel Museum, Jerusalem), is nearly identical to the MT dated approximately 1,000 years later. The MT chronology is attested in the first-century pseudepigraphal work Life of Adam and Eve, meaning that an MT-like text had to exist before that, even though there is no earlier surviving manuscript.

The Septuagint (LXX) is the Koine Greek translation of the Old Testament, earliest preserved in the codices Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus from the AD 350s. However, the LXX chronology is used by Demetrius the Chronographer in the late third century BC, whose work is only preserved in fragmentary quotes by Eusebius in the fourth-century Praeparatio evangelica remain (Charlesworth 1983, 851–852). This indicates that the LXX’s chronology diverged from the MT’s either at the time of translation or very soon after.

The Samaritan Pentateuch (SP) is a text of the Torah preserved by the Samaritans that is distinctive in several ways. It is written in the ancient Hebrew script and shows some signs of being altered to fit the theological distinctives of the Samaritans. Samaritans claim, rather, that the MT has been altered for the theological interests of the Jews and that their oldest text, the Abisha scroll, is over 3,000 years old and was written by Aaron’s great-grandson. However, even if the text began as a document penned by Abisha, the current state of the scroll shows that there was damage, repair, and wholesale replacement of parts that were lost—including the parts which would shed light on the current discussion which contained the Genesis 5 and 11 genealogies (Crown 1991). The earliest extant manuscript is believed to be Add. 1846, which dates to the early twelfth century AD (The Library at Southeastern n.d.). The SP chronology, however, is attested in the book of Jubilees, of which many fragments were found with the Dead Sea Scrolls dated ca. 100 BC (Charlesworth 1983, 43). Therefore, all three texts were extant and in use by various communities by the time of Jesus and the authoring of the New Testament in the first century AD.

After these texts diverged, their respective copyists had tendencies that caused the texts to differ at various points. One analysis of the three texts of Genesis resulted in 860 textual variants, not including orthographic elements. An examination of the types of changes and where the various texts agree or disagree with each other leads to the conclusion that the MT text type preserves the earliest text of Genesis. After it split off from the tradition that gave rise to both the SP and LXX, all versions of the text continued to be copied and continued to gain variants. The SP and LXX text types split from each other before the translation of the LXX (Steinmann 2021).

The Three Texts of Genesis 5

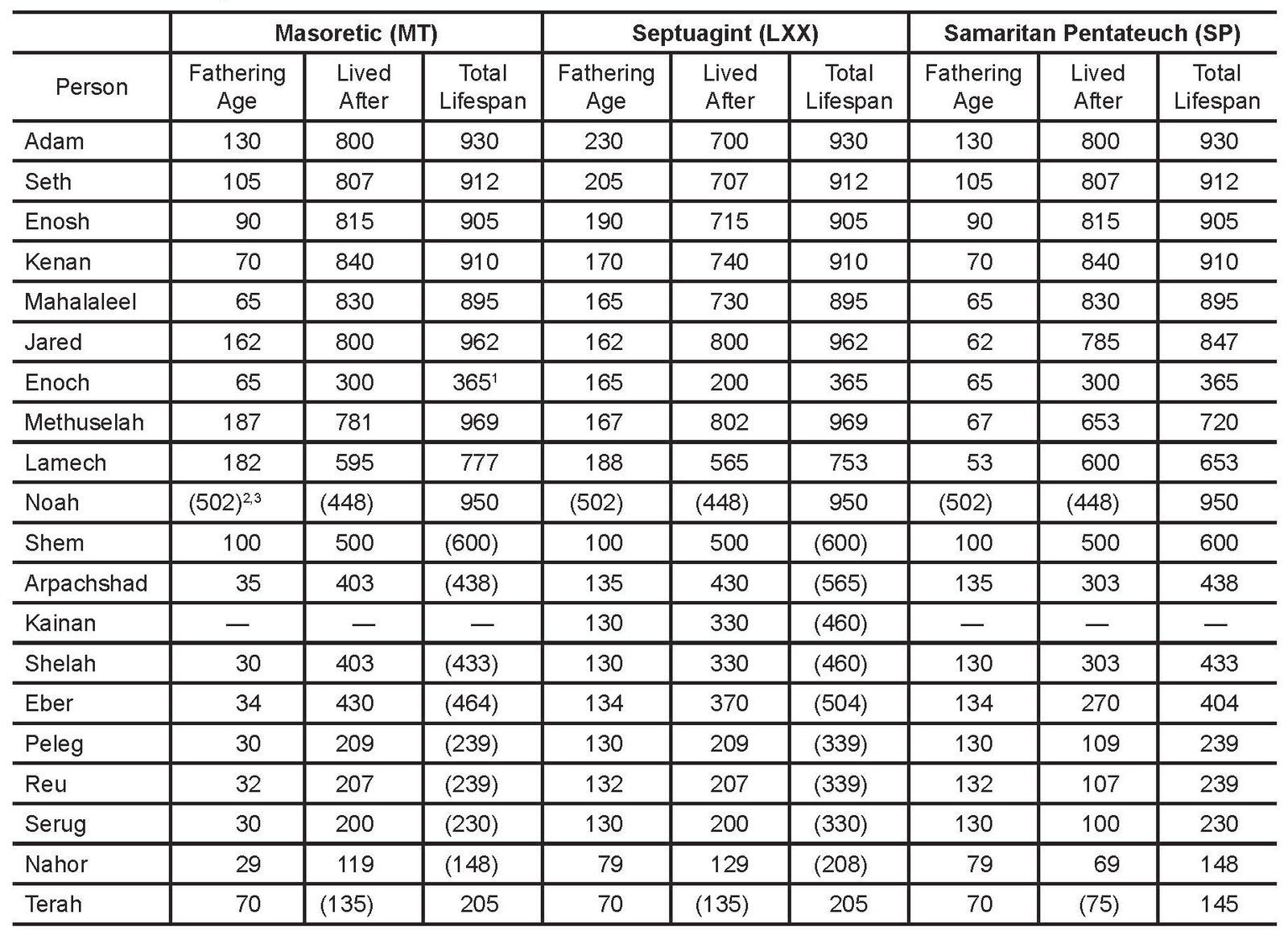

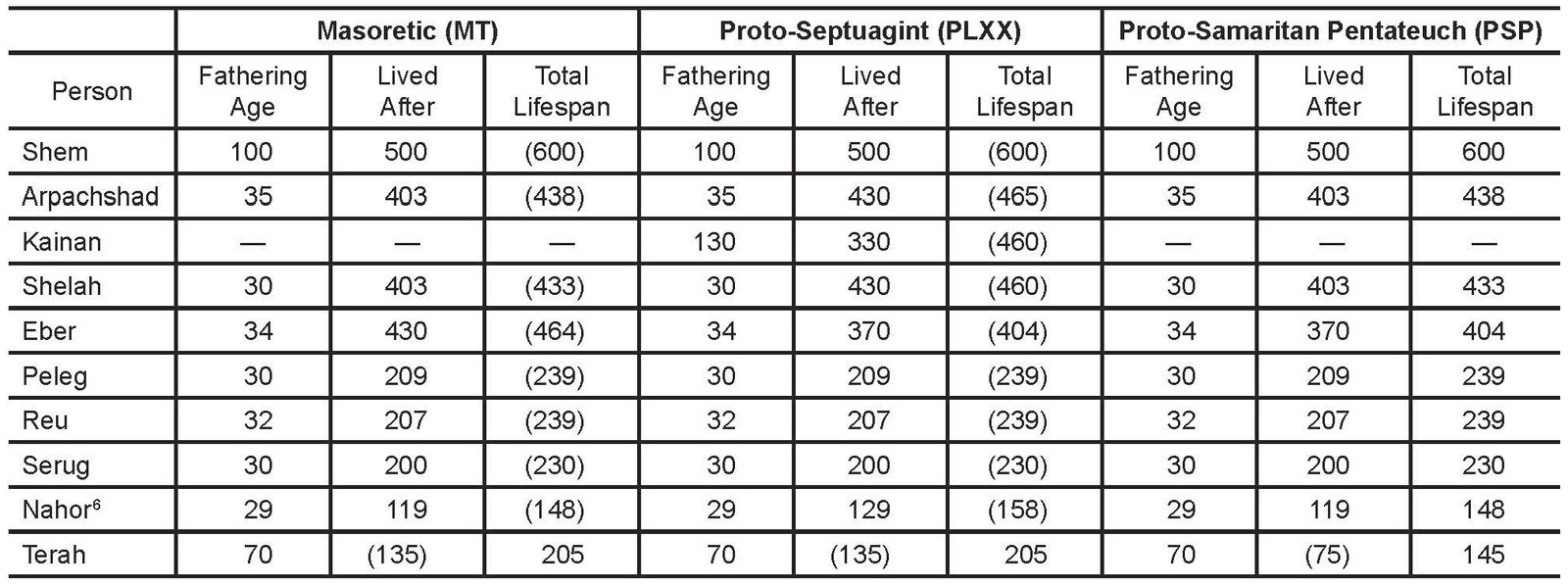

Table 1 summarizes the chronological data from Genesis 5 and 11 as preserved in the MT, LXX, and SP.

While all three texts preserve substantially different chronologies, there are enough similarities to show that they share a common source. Many of the changes that introduce differences are systematic, so they can be reversed to produce hypothetical texts that can be used for further analysis.

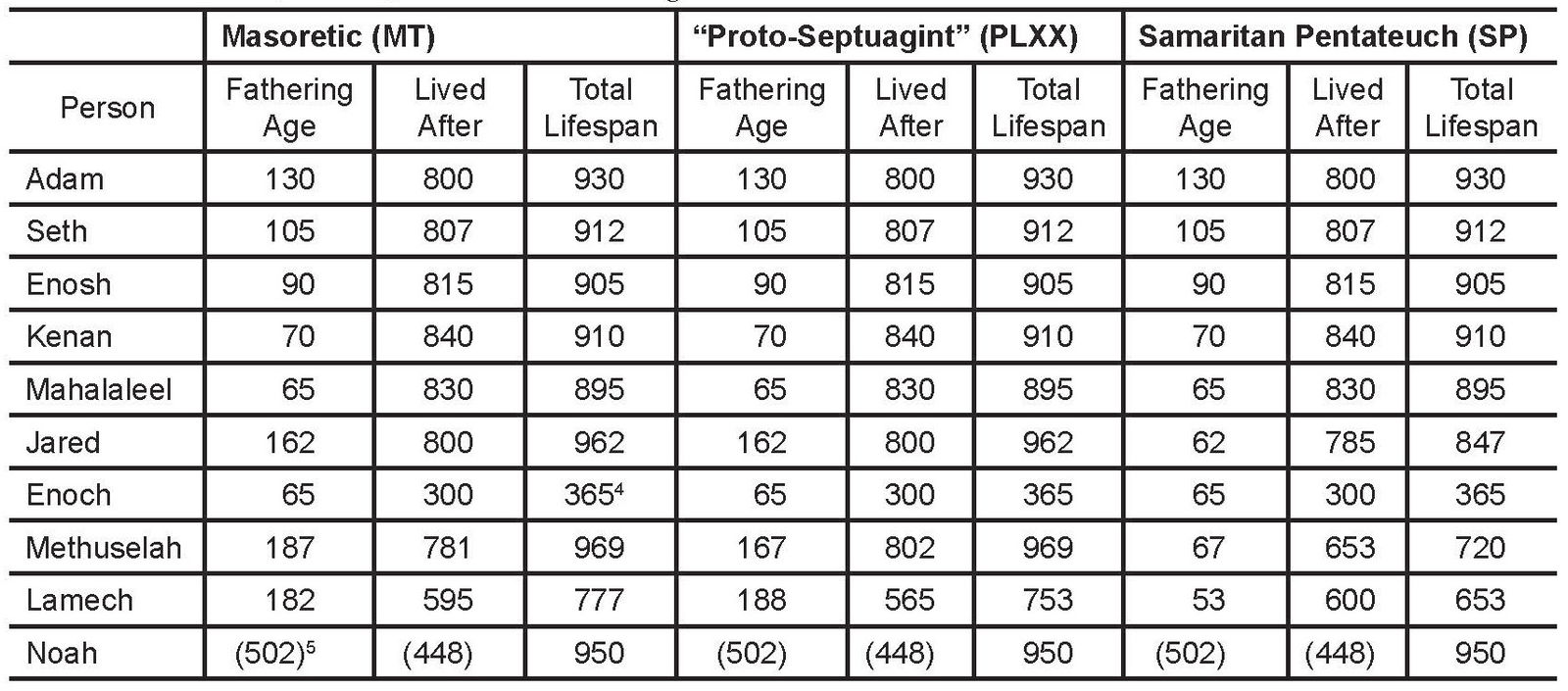

First, LXX Genesis 5 shows systematic inflation of the fathering age of many (but not all) of the patriarchs with deflation of the remaining lifespan to keep the total lifespan the same. Because this was a systematic change, the inflation and deflation may be reversed to create a hypothetical text we will term the “proto-Septuagint” (PLXX). Investigating the motive behind this systematic change is beyond the scope of this paper, which simply seeks to establish its existence. Although this hypothetical text is not preserved in any manuscript, reversing this obvious and intentional change can help us compare the three texts. Furthermore, designating this hypothetical text as the PLXX is not meant to suggest that it ever existed as a Greek text preceding the LXX—the evidence suggests that the inflation took place at or soon after the time of the translation of the LXX.

Reversing the systematic changes to LXX Genesis 5 highlights the similarity between the three texts of Genesis 5. Note that Jared’s, Methuselah’s, and Lamech’s LXX (table 2) “lived after” figures were not lessened by 100 years. This suggests that there were exceptions to the otherwise systematic changes.

One note in MT Genesis 5’s favor is that all of Noah’s ancestors die before the global flood which only the eight Ark passengers survived, with Methuselah dying the year of the Flood. In the LXX and PLXX, Methuselah lives 14 years after the Flood, while the SP obviously truncates the remaining lifespans of Jared, Methuselah, and Lamech to prevent all three living past the Flood. Unless one prefers to argue that divine inspiration cannot ensure a text that stands up to basic arithmetic, the MT must be preferred.

Smith’s Case for the 187 LXX Begetting Age for Methuselah

Smith, an ardent advocate for the primacy of the LXX text in Genesis 5 and 11, argues that the early LXX text gave Methuselah a begetting age of 187 years, rather than the extant LXX reading of 167 (Smith 2017). Incidentally, MT advocates would agree. This is because the LXX text is derived from the MT which has the original begetting age. The SP and LXX share the 67 error, indicating that the scribal error may have occurred in Hebrew before the translation of the Septuagint.

Smith’s paper gives a convincing argument for 187 being the original reading for Methuselah’s begetting age. However, explaining how this error came to be does not establish the LXX as the text that most closely matches the original, especially when another text has that same begetting age.

Lamech

The three entries for Lamech differ wildly. Because the Masoretic shows evidence elsewhere in this genealogy of being the better-preserved text, we are justified in attempting a reconstruction that assumes an MT-like original in the absence of evidence that one of the other texts preserves a superior variant. The Hebrew for 182 years is שׁתּים וּשׁמנים שׁנה ומאת, or literally “two and eighty years and one hundred.” If a copyist misread this as שׁמנת וּשׁמנים שׁנה ומאת (“eight and eighty years and one hundred”), this would explain an origin of the variant that would not have been caught by simply counting the number of characters, a Masoretic practice.

To explain the remaining lifespan, a LXX variant would similarly require changing המשׁ ותשׁעים (five and ninety) to המשׁ ושׁשׁים (five and sixty). This is not as likely a change because it would involve changing the number of characters in a Hebrew manuscript. However, if the error happened at the time of the translation, a scribe could mishear the word for 90 as the word for 60, or misread it. The change happening at the time of translation, when it would not be checked against another manuscript in the same language, is perhaps slightly more likely than the change happening after the translation into Greek, from ἑξήκοντα to ἐνενήκοντα. From there, a later copyist could simply “correct” the total lifespan, noting that a lifespan of 777 years within the Septuagint chronology would have Lamech living past the Flood.

The Samaritan Pentateuch’s figures for Lamech are hopelessly corrupted, but in an obvious recension (a version of the text that is characterized by deliberate changes) like the SP, that is to be expected, though the fact that Lamech’s total lifespan in the LXX and SP is 100 years apart is noteworthy.

The Chronology of Genesis 11

Much like in Genesis 5, there are systematic changes to the texts of Genesis 11 that can be reversed to aid in analyzing its history. Here, we will reverse the systematic inflation in both the LXX and SP timelines. It is known that these two texts inflate the chronology, rather than the MT deflating the chronology, because at an early point in the transmission of the SP, when it still had MT-like figures, a copyist with a systematizing tendency, among other things, added total lifespan figures to the Genesis 11 genealogy to make it fit the pattern of the Genesis 5 genealogy. The total lifespan figures agree with the MT overall.

It is evident that the total lifespan figures were added to the SP rather than removed from the MT because the LXX engaged in the same inflation of the fathering age as it did in Genesis 5, but without a total lifespan figure, they did not need to deflate the remaining lifespan figure. When these figures disagree with the MT, it is because of other textual errors. Table 3 reverses these changes to create the hypothetical texts “proto-Septuagint” (PLXX) and “proto-Samaritan Pentateuch” (PSP) and compares them with the MT.

The MT is more similar to the texts of the PLXX and the PSP than it is to the extant texts of the LXX and SP. This reveals the remaining differences which are more significant for reconstructing the textual history.

The text tradition for PLXX and PSP seems to have split from the MT before further splitting into the traditions that would become the PLXX and PSP. They also may have been influenced by Jubilees, which existed and was circulating at that time.

Table 3. The MT, PLXX, and PSP chronologies of Genesis 11.6

Arpachshad, Kainan, and Shelah

Kainan is so widely recognized as an addition to the original text that the burden of proof is on anyone who wishes to argue otherwise. Wenham suggests it was motivated “by the desire to produce a list of ten ancestors like that of chap. 5 as well as to stretch out the period from Shem to Abraham as much as possible” (Wenham 1987). Further evidence that Kainan was an ancient addition to the genealogy is seen in his absence in LXX 1 Chronicles 1. The most likely scenario to explain Kainan’s inclusion in Luke 3 is that Kainan was added to an early copy of Luke 3 as a copyist error and Christian scribes then introduced the error to LXX Genesis 11 (remembering that most copies of the LXX are Christian manuscripts), Jubilees, Josephus (remembering that Christian scribes left their mark in other places of importance for them), and some copies of LXX 1 Chronicles 1 (Steinmann 2017).

Arpachshad and Shelah have remaining lifespan figures of 430 and 330 years, respectively, instead of the MT’s 403 and 303 years, respectively. This is explained as a simple copyist error. In the case of Arpachshad, there was confusion between the original שׁנשׁ שׁנים (3 years) and שׁלשׁים שׁנה (30 years). Likewise in the case of Shelah, the same confusion occurred (Klein 1974).

Eber

This is the only entry in the genealogies which textual analysis suggests the MT may not preserve all the original figures. The PLXX and PSP agree against the MT which is a strong indication that these were the original numbers. However, the only number the MT does not preserve is the remaining lifespan age of Eber, which does not affect the chronology. As Klein (1974) explains, “LXX’s 370 is original, and SP is predictably 100 less. MT should be 370; its present reading results from a confusion with the age given for Eber at the birth of his first born ארבע ושלשים שנה and a subsequent metathesis: מאות שנה] שלשים שנה וארבע]” (Klein 1974).7

Discussion

The textual differences between the MT, LXX, and SP have been noted for as long as Jews and Christians have been reading the texts, and even ancient authors tried to reconstruct when and why these differences were introduced. Eusebius believed that the Masoretic ages were reduced to encourage early marriage (Smith 2017). Augustine believed the LXX ages were inflated to imply that one of their years was ten of ours, to make the long chronologies more plausible (Augustine 2009, 431–432). Today, there are a similar proliferation of explanations for why the texts differ.

It is impossible to say with absolute certainty what happened in a text’s history when no texts from that point in time are available for us to study. However, we can construct a probable history using the texts that are extant. Other reconstructions are possible; however, a reconstruction with an LXX-like progenitor is much less parsimonious than the current reconstruction with an MT-like progenitor.

Conclusion

This textual analysis provided by this paper shows that the MT is the better-preserved text and that the MT chronology was changed to create the chronologies in the LXX and SP, rather than the LXX or the SP being original. The others do have value and can be consulted when the MT by itself is unclear. However, they are secondary texts that are clearly recensions. To argue that an LXX text-type gave rise to the MT and SP text-types, one must thoroughly analyze the data and propose an alternative reconstruction with equal or greater explanatory power.

References

Augustine. 2009. The City of God. Translated by Marcus Dods. Peabody, Massachusetts, Hendrickson Publishers.

The Library at Southeastern, n. d. “Biblical Manuscripts: Samaritan Hebrew Manuscripts.” https://library.sebts.edu/c.php?g=457318&p=5847648.

Crown, Alan D. 1991. “The Abisha Scroll–3,000 Years Old?” Bible Review 7 (October 5). https://library.biblicalarchaeology.org/article/the-abisha-scroll-3000-years-old.

Charlesworth, James H. 1983. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. Vol. 2. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson.

Klein, Ralph W. 1974. “Archaic Chronologies and the Textual History of the Old Testament.” The Harvard Theological Review 67, no. 3 (July): 255–263.

Smith, Henry B. Jr. 2017 “Methuselah’s Begetting Age in Genesis 5:25 and the Primeval Chronology of the Septuagint: A Closer Look at the Textual and Historical Evidence.” Answers Research Journal 10 (August 2): 169–179. https://answersresearchjournal.org/methuselah-primeval-chronology-septuagint/.

Steinmann, Andrew E. 2017. “Challenging the Authenticity of Cainan, Son of Arpachshad.” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 60, no. 4: 697–711.

Steinmann, Andrew E. 2021. “A Comparison of the Text of Genesis in Three Traditions: Masoretic Text, Samaritan Pentateuch, Septuagint.” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 64, no. 1: 25–43.

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, n. d. “The Digital Dead Sea Scrolls.” http://dss.collections.imj.org.il/isaiah.

Wehman, Gordon. 1987. Genesis 1–15. Word Biblical Commentary. Vol. 1. Dallas, Texas: Word Incorporated.