The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

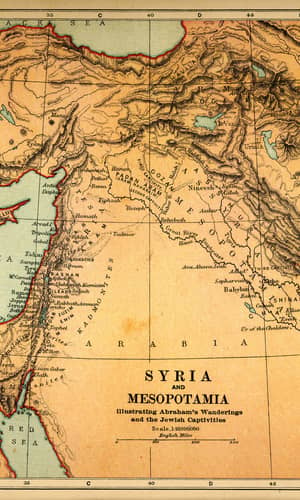

Mesopotamia, the land that is today part of Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, is home to one of the oldest civilizations to have ever been discovered. It is here that the civilizations of Sumer, Babylon, and Assyria existed. This land is noteworthy in the Bible because it was here that the exiles were taken captive after the destruction of Jerusalem. It was also here that Abraham had lived before he set out to the Promised Land. For many years, Abraham was believed to have lived at the same time as Hammurabi, king of Babylon. Later scholars would date Abraham to the period shortly before the reign of Hammurabi. However, the result of recent research is that the chronology of the ancient world is being redated. Hammurabi now appears to be a near contemporary of Moses instead of Abraham. In Egyptian chronological studies, the patriarchs are dated earlier than ever before. In spite of this, there has been little research conducted on the relationship between Abraham and Mesopotamia in this new chronological revolution. This article will look at the current trends in chronological studies and how they relate to the life of Abraham. It will come to the conclusion that Abraham lived much earlier in Mesopotamian history than what most have realized.

Keywords: Abraham, Mesopotamia, Ebla, Ancient Chronology, Sodom and Gomorrah

Introduction

Mesopotamia was one of the earliest regions to be inhabited after the great Flood, and it was here that Abraham lived his early life. In addition to this, it was from the region of Mesopotamia and other eastern nations that a coalition of kings fought against Sodom and Gomorrah and kidnapped Lot, Abraham’s nephew. Although not nearly as popular in the account of the patriarchs as Egypt, Mesopotamia is an important topic for any who undertake research into the historical background of the book of Genesis. This paper will examine the chronological data known from early Mesopotamia and will attempt to find the historical background of Abraham and the events during his life. This current study will not look at the pre-Abrahamic period as this would go beyond the scope of this article. Instead, by placing Abraham into Mesopotamian history it will allow creationists to have an anchor point to study the rich pre-Abrahamic period and have a better understanding of the development of civilization after the Tower of Babel.

Ancient Mesopotamian Chronology

Placing Abraham into the Mesopotamian account has had an interesting history. Before this topic is examined let us briefly look at the chronological history of Mesopotamia as it is understood today by scholars.

Table 1 presents the traditional chronology of early Mesopotamia from the Hassunah period to the end of the First Dynasty of Babylon when Hammurabi lived. One should notice that some of these dynasties overlap considerably. A Bible-believing Christian will, of course, reject the dating of the oldest periods but, as mentioned in the introduction, this paper will not discuss these older periods as it will be shown below that they will have no effect on how we date Abraham. Our focus (as it will be understood shortly) will be on the Early Dynastic Period and afterwards.

| Traditional Chronology of Early Mesopotamia | |

|---|---|

| Hassunah period | 5800–5500 BC |

| Halaf period | 5500–4500 BC |

| Ubaid period | 5300–3750 BC |

| Warka (Uruk) period | 3750–3150 BC |

| Protoliterate (Jamdat Nasr) period | 3150–2900 BC |

| Early Dynastic I | 2900–2750 BC |

| Early Dynastic II | 2750–2600 BC |

| Early Dynastic IIIA | 2600–2500 BC |

| Early Dynastic IIIB | 2500–2334 BC |

| Dynasty of Akkad (Sargon the Great) | 2334–2154 BC |

| Dynasty of Gutium | 2217–2120 BC |

| Reign of Utu-khegal | 2120–2112 BC |

| Ur III Dynasty | 2112–2004 BC |

| Dynasty of Isin | 2017–1787 BC |

| Dynasty of Larsa | 2025–1763 BC |

| First Dynasty of Babylon (Hammurabi) | 1894–1595 BC |

History of Dating Abraham in the Mesopotamian Account

During the 19th and early 20th centuries Abraham was considered to be a contemporary or near-contemporary of Hammurabi, the great king of the First Dynasty of Babylon. William Petrie, in his book Egypt and Israel (Petrie 1911, p. 17), was making this connection as he placed Hammurabi around 2100 BC. Henry Sayce, around the turn of the century, was dating Hammurabi to 2356–2301 (Sayce 1894, p. 120) and Leonard King, in his A History of Babylon, was dating Hammurabi to 2123–2081 (King 1915, p. 319). In fact, dating Hammurabi in the range of c. 2250–2100 was the standard in the early twentieth century and even later (Jastrow 1915, pp. 146, 149; Rogers 1915, p. 80; Winckler 1907, p. 59).1 Even Henry H. Halley, in his popular Bible handbook, and H. C. Leupold, in his popular commentary on Genesis, were dating Abraham and Hammurabi to the same period (Halley 1965, p. 97; Leupold 1942, p. 447).2 Today, Hammurabi is dated to about 1792–1750 (Roux 1992, p. 506).

This depends upon the different interpretations concerning biblical chronology.

Today the usual dating of Abraham in Mesopotamia is in either the Ur III or Isin-Larsa periods (see table 1). This depends upon the different interpretations concerning biblical chronology.3 Kenneth Kitchen, for instance, dates the oppression of the Israelites in Egypt from c. 1320–1260/1250 and the Exodus around 1260/1250 and uses a 645 year period between Abraham and the Exodus. This gives a date for the period between Abraham and Joseph from around 1900–1600 (Kitchen 2003, pp. 358–359).4 This would place Abraham during the Isin-Larsa period.

There are other ways of dating Abraham including the use of the popular date of 1446 for the Exodus and 645 years between Abraham and the Exodus. Using this method one will date Abraham’s 75th year in the year 2091 during the Ur III period. It is during this period that Gleason Archer has placed Abraham (Archer 2007, p. 183). With 430 years between Abraham’s 75th year and the Exodus he would have arrived in Canaan in the year 1876 during the Isin-Larsa period like Kitchen dates him. Alfred Hoerth, in his Archaeology and the Old Testament, uses this method to date Abraham to this period (Hoerth 1998, pp. 58–59).

Using Ussher’s date of 1491 for the Exodus and 645 years Abraham would have entered Canaan in the year 2136 during the reign of the Gutium. Using 430 years would place the same event in 1921 during the Isin-Larsa period. To make things even more complicated many scholars seem to date Abraham (and the other patriarchs) to the Middle Bronze Age without being specific on whether Abraham lived during Ur III or Isin-Larsa (Albright 1963, pp. 4, 7; Bright 1981, p. 83; LaSor, Hubbard and Bush 1996, pp. 41–43; Rooker 2003, pp. 233–235).5

One of the biggest pieces of evidence used for dating Abraham to the Isin-Larsa period is the fact that Abraham fought a coalition of four kings from the East during a period when each city-state had its own ruling dynasty of kings (see Genesis 14). This event had to have been at a time in Mesopotamian history when no individual dynasty had complete control over the region. Kenneth Kitchen explains it well:

However, by contrast with the Levant, this kind of alliance of eastern states was only possible at certain periods. Before the Akkadian Empire, Mesopotamia was divided between the Sumerian city-states, but this is far too early for our narrative (pre-2300). After an interval of Gutian interference, Mesopotamia was then dominated by the Third Dynasty of Ur, whose influence reached in some form as far west as north Syria and Byblos. After its fall, circa 2000, Mesopotamia was divided between a series of kingdoms, Isin, Larsa, Eshnunna, Assyria, etc., with Mari and various local powers in lands farther north and west. This situation lasted until the eighteenth century, when Hammurabi of Babylon eliminated most of his rivals. From circa 1600/1500 onward, Assyria and Babylon (now under Kassite rule) dominated Mesopotamia, sharing with none except briefly Mitanni (ca. 1500 to mid-thirteenth century) within the Euphrates’ west bend, and the marginal Khana and Sea-land princedoms were eliminated in due course. Thus, from circa 2000 to 1750 (1650 at the extreme), we have the one and only period during which extensive power alliances were common in Mesopotamia and with its neighbors (Kitchen 2003, p. 320).

A New Twist

Kitchen explains it well why so many modern scholars date Abraham to the Isin-Larsa period. However, the search for the Mesopotamian background for Abraham does not stop there. In 1974, the archaeological world was rocked with the discovery of the archives of the ancient city of Ebla in Syria. The archives of the city dated back to before the days of the Akkadian Empire (see table 1). These texts reveal that Ebla was a thriving commercial city with contacts stretching in all directions for hundreds of miles. The discovery affected not only Near Eastern studies but also biblical studies. Shortly after this discovery David Noel Freedman argued that the discovery of the archives gave evidence for placing the patriarchs into the period of Mesopotamian history before Sargon, the founder of the Akkadian Empire. This would have been the period which Kitchen said was too early for the patriarchs. Freedman noted:

The true significance of the Ebla tablets for biblical history and our understanding of the patriarchal narratives [is revealed]. The Genesis 14 account of the punitive raid of the kings of the East upon a rebellious coalition of kings from the Cities of the Plain has long been a puzzling problem for scholars in reconstructing biblical history. The amazing correlation of the number, order, and names of the Cities of the Plain between the Ebla tablet and the biblical record indicates that the Genesis 14 narrative should be understood in the setting of the third millennium, not in the second or even first millennium as scholars have previously thought (Freedman 1978, p. 143).

Freedman stated that one of the tablets listed the five Cities of the Plain in the same order in which they were listed in Genesis. It even named one of the five kings in almost the same form as Genesis (Birsha). This allowed Freedman to say that the patriarchs lived in the Early Bronze Age (EBA) which is traditionally dated to the third millennium BC (Freedman 1978, pp. 148, 154–155, 157–158). Freedman went on to argue that the Early Bronze Age remains just east of the Dead Sea were where the five cities were located. It was believed that Bab edh-Dhra and four other sites nearby were the Cities of the Plain. This was backed up by the fact that there were no Middle Bronze Age sites in the area but only Early Bronze Age sites. Interestingly the Early Bronze Age was the same period as the Ebla archive (Freedman 1978, p. 152).

It is now accepted by most scholars that Freedman’s conclusions are false. The tablet does not list all five of the cities and concerning the name of Birsha, John Bimson notes that there are several examples of kings with the same name ruling centuries apart. So just because the name sounds like that of the king mentioned in Genesis 14 does not mean that it was him (Bimson 1980, pp. 66–67). Freedman himself even noted that the king named Birsha ruled not in Gomorrah but in Admah, contrary to what Genesis says (Freedman 1978, p. 155).

Bimson also argues against Freedman’s archaeological evidence. He notes that Freedman’s argument depends on the fact that no Middle Bronze I sites have been discovered so that Freedman must assume that the Early Bronze Age sites are the Cities of the Plain. Bimson says:

Unless the EBA settlements can be identified with certainty as the “cities of the plain” (which would require four of them being shown to have suffered a simultaneous fall in the EBA; Zoar was not destroyed according to [Genesis] 19), Freedman’s case remains weak (Bimson 1980, p. 67).

He also notes other problems with Freedman’s identification when he says that the central Negeb is pivotal to the patriarchal narratives and that there is almost a total absence of Early Bronze Age evidence in this region until the Middle Bronze I period (Bimson 1980, p. 67). Lastly, biblical chronology cannot be stretched back that far into the third millennium BC. Dating Abraham back before 2300 BC is simply too much of a strain on biblical chronology according to both Bimson (1980, p. 67) and Hoerth (1998, p. 73).

In summary, most scholars date Abraham to the Middle Bronze Age in which is the period of either Ur III or the Isin-Larsa period. It is clear that one piece of evidence as to why Abraham is dated to these periods is the nature of the Genesis 14 coalition of kings. However, it must be noted that the number one reason for this dating is the acceptance of the standard chronology of the Ancient Near East. Abraham is dated anywhere between c. 2100 and c. 1900 and this range of dates are then applied to the standard chronology of Mesopotamia.

However, there have been a number of scholars who have come out against the standard chronology in the recent past.6 There has been a concentrated effort to use this new research in ancient chronology to correlate biblical events with Egyptian chronology.

Two separate studies have dated Abraham to sometime during the Early Dynastic or the Old Kingdom periods in Egypt. John Ashton and David Down (2006) have dated him to the Fourth Dynasty while this author (McClellan 2011, p. 155) has given a range of dates from the 2nd–6th Dynasties.7 Placing Abraham in this earlier period in Egyptian history also forces Abraham to be dated significantly earlier in Mesopotamian history. (Ur III and Isin-Larsa correspond to the Middle Kingdom in Egypt, and that time aligns better with the Mosaic period than with Abraham’s.)

If Abraham is to be dated earlier in Mesopotamian history then in what period did Abraham live in Mesopotamia? What is interesting about the quote by Kitchen above is that he notes that there was another period in Mesopotamian history in which a coalition of kings could have existed; that is, the period before the Akkadian Empire. What is more interesting is that this is the time period that Freedman dated Abraham. So one has to ask whether or not this period could be the setting for Abraham’s life?

Egypt, Ebla, and the Chronology of Mesopotamia

Noted above were two important pieces of information that are vital for this study. First, the fact that both this author and Ashton and Down have dated Abraham to the Early Dynastic or Old Kingdom periods of Egypt; and second, the discovery of the city of Ebla in Syria. What is significant about both of these facts is that they can be used to show in what period in Mesopotamian history Abraham lived.

The city of Ebla is located in present-day Syria. The city was discovered in the remains of Tell Mardikh. Among the findings discovered was the city’s archive located in the palace. Archaeologists have designated this palace as palace G. Interestingly palace G is dated to the Early Bronze Age. The archive includes more than 17,000 complete and fragmentary documents. Included are letters, administrative, economic, juridical, lexical, and literary texts which give us information concerning the city’s social, economic, and governmental structure, as well as the religion of the city (Archi 1997, pp. 184–185; Matthiae 1997, p. 181). The Ebla tablets were written during the reigns of the last three kings of Ebla and thus constitute a “living” archive (Archi 1997, p. 184; Astour 2002, p. 59; Matthiae 1997, p. 181).8

The Sixth Dynasty is the latest that Abraham could have been in Egypt.

The Ebla archives allow us to connect Mesopotamian chronology with Egyptian chronology during this early period at one very specific point: the name of Pepi I (of the Sixth Dynasty) was found among the ruins of palace G (Archi 1997, p. 184; Astour 2002, p. 60; Gelb 1981, p. 58; Matthiae 1997, p. 181; Pettinato 1986, p. 58). The name of Pepi I (along with another Egyptian king—Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid during the Fourth Dynasty) was found in undisturbed layers of the debris of palace G which shows us that it was not placed there after the destruction of the palace archive (Astour 2002, p. 60).

The Sixth Dynasty is the latest that Abraham could have been in Egypt (McClellan 2011). Since Pepi I was a king during this dynasty and is dated to the period before the destruction of palace G, we can use the palace archives to date Abraham within Mesopotamia history. The question is to which period in Mesopotamian history does palace G correlate? There are different opinions, but Ebla is dated using thousands of texts discovered there to show that the palace was destroyed before or sometime during the Akkadian Empire.

Sargon and his grandson, Naram-Sin, the first and fourth kings of Akkad, have been the two most cited kings who could have destroyed palace G. Both kings boast that they conquered Ebla (Bermant and Weitzman 1979, p. 172). Paolo Matthiae is one scholar who believes that palace G was destroyed by Naram-Sin. He notes that the name Shariginu in a text found at Ebla may be Sargon and that Akkad is mentioned as A-ga-duki EN (Matthiae 1977, pp. 166–167). These two names would mean that Sargon reigned during part of the Ebla dynasty before the destruction of palace G (Matthiae 1977, pp. 168–169). To support the theory of Naram-Sin as the conqueror, the pottery found at Ebla seemed to correspond to the period of Naram-Sin, suggesting that he was, in fact, the conqueror of Ebla and destroyer of palace G (Bermant and Weitzman 1979, p. 170).

However, there are problems with this thesis. Bermant and Weitzman (1979, p. 172) note that the pottery once thought to belong to the period of Naram-Sin now is believed by some scholars to date to the period before Naram-Sin. Names originally translated as Sargon and Akkad were shown to be a nonentity called Shariginu and an unimportant town named Arugadu (Bermant and Weitzman 1979, p. 174).

Besides these problems, there are others as well. Astour (2002, p. 64) notes that there is no mention at all of Akkad in the Ebla tablets. “They [the Ebla texts] reflect a world that is sharply different from the era of Naram-Sin [and Sargon as will be discussed below].” This contradicts the belief that Sargon was concurrent with palace G. Also concerning Sargon there is an inscription noting that he conquered Ebla during one of his conquests but Astour believes that Sargon did not destroy the archives (Astour 2002, p. 68). He notes that the very latest documents found at Ebla mention that the king of Mari was still ruling his city. If he was still on the throne, then it is clear that the city had not yet been conquered by Sargon. Astour says:

For obvious geographical reasons Sargon could not have destroyed Ebla before Mari, and the news of Mari’s fall would have reached Ebla much faster than it would have taken Sargon’s army on its long roundabout march. Hence, the fire of palace G occurred before Sargon’s northern expedition and could not have been inflicted by him (Astour 2002, p. 71).

So who destroyed palace G at Ebla? There are a number of other theories which all point to the period preceding the rise of the Akkadian Empire. Pettinato (1981, p. 107; 1986, p. 63) gives a few different theories that it may have been either a king in the city of Kish, Eannatum, king of Lagash, who conquered both the cities of Kish and Mari, or Lugalzagesi, king of Uruk who conquered to the Mediterranean Sea, who could have conquered Ebla.

There is, however, an even more interesting theory. Astour (2002, p. 74) believes that palace G’s destruction predated the Akkadian Empire but that it was not destroyed by an invader. He believes that it may have been destroyed by a fire, which may have been accidental or perhaps even the result of arson. He notes that the rest of the city was not destroyed at the same time as the palace. Furthermore, the destruction of palace G does not seem to be followed by a break in the cultural development of the city. He notes that history records many other buildings destroyed not by an invader but rather by arson or even an accident.9 Even Pettinato has noted this when he says:

Could trouble have come from another quarter that we are unable to identify at the moment? In two Ebla letters, Crown Prince Dubuhu-Ada, who never came to power, was cautioned “to be on his guard” by two governmental officials. This blends with the curious fact that in the audience court some tablets were discovered on wooden tables, almost as if the scribes had been surprised by an assault on the palace during their routine work. Could the destruction of the palace perhaps have been the work of Eblaites involved in a power struggle with the government? (Pettinato 1986, pp. 63–64)

Is there any evidence that could support a destruction date of palace G before Sargon, as the arsonist-theory or accident-theory requires? Gelb (1981, pp. 57–58) says quite confidently that the Ebla archive is to be dated to the period before the Akkadian empire in Mesopotamian history. There is, in fact, a large amount of evidence for dating palace G to this period. This evidence would place the archive in the time known to scholars as the Early Dynastic Period.

- The paleography and composition of the Ebla tablets correspond to the tablets found at the Mesopotamian cities of Fara, Mari, Kish, and Abu Salabikh10 dated to the period before Sargon. Ebla also had a cultural relationship with Mari and Abu Salabikh (Astour 2002, p. 62; Bermant and Weitzman 1979, p. 174; Gelb 1977, pp. 6–8, 12, 14; Gelb 1981, pp. 56–57; Pettinato 1986, p. 58).

- The historical perspective of the Ebla tablets is of the period before Sargon when Kish and Mari were the centers of attention. Kish is actually the most mentioned place in the texts along with the city of Adab11 while there is no hint whatsoever of the Akkadian Empire anywhere in the texts (Astour 2002, p. 64; Bermant and Weitzman 1979, p. 174; Gelb 1981, p. 58; Pettinato 1981, p. 73; 1986, pp. 58–59).

- Pettinato mentions a study . . . has shown that the Akkad era could never have coincided with Ebla inasmuch as the geographical perspective of the [Ebla] texts is completely different [from that of the Akkadian period] (Pettinato 1986, p. 61).

- The ratio between silver and gold is also an issue. The ratio between these two precious metals was 5 to 1 during the time of King Ebrium of Ebla, 4 to 1 during the time of his son and successor Ibbi-Sipis, and 9 to 1 during the Akkadian period (Pettinato (1986, p. 61).

All of this information is essential to this study because this means that palace G at Ebla could not have been burned down prior to the reign of Pepi I.12 This evidence indicates that the beginning of the Akkadian Empire could not have been any earlier than the reign of Pepi I and may have been later. This conclusion is crucial since if Abraham is to be dated no later than Pepi I then Abraham would have lived during the Early Dynastic Period of Mesopotamia (more on all of this below). If he lived afterwards, there is a possibility that he lived during the early years of the Akkadian Empire. However, there is other evidence that supports that the patriarch would have lived before the reign of Sargon and not afterwards.

Identity of Genesis 14 Kings

This other piece of evidence is to be found in the 14th chapter of Genesis. In this chapter, four kings from outside of Palestine invade and fight against five Canaanite kings. The former kings are Amraphel king of Shinar, Arioch king of Ellasar, Kedorlaomer king of Elam, and Tidal king of Goiim. Remember earlier in this article that Kitchen believed that there were two periods in Mesopotamian history that could accommodate the events in this chapter: the Early Dynastic period and the period between Ur III and Hammurabi. Above, we showed that it is likely that Abraham is to be dated to the Early Dynastic Period. The question is then, “Does the evidence from Genesis 14 fit with the known political history of the Early Dynastic Period?” Let us look at the evidence available for each of these kings.

Amraphel of Shinar is the first king mentioned in the narrative. In the past, he was believed to be the same as Hammurabi. However, scholars have now rejected this connection and Hammurabi is now dated later than Abraham (Leupold 1942, p. 447; Morris 1976, p. 312). However, most scholars still place Amraphel in Babylon (Leupold 1942, p. 447; Morris 1976, p. 312; Wenham 1987, p. 308). Kitchen (2003, p. 320) says “the name of his kingdom, Shin’ar, stands for Babylonia (cf. Genesis 10:10) in Hittite, Syrian, and Egyptian sources in the later second millennium.” Victor Hamilton (1990, p. 400) notes that since Genesis 11:2 and Zechariah 5:11 equate Shinar with Babylon, Amraphel must have ruled there.

Aalders breaks the normal equation with Babylon by noting that some scholars have identified Amraphel with Amorapil, who may have been a king of a territory known as Sanhar. He says “[t]his kingdom supposedly lay in northwestern Mesopotamia.” He continues, “However, we cannot be certain of the exact identification of this king and his realm” (Aalders 1981, p. 282). There does, in fact, seem to be some evidence which points to Sanhar as a possible region for the identification of the kingdom of Amraphel. Anne Habermehl (2011) has postulated that the land of Shinar was not the same as Babylon but was, in fact, in northern Mesopotamia.

She argues that Shinar was not in southern Mesopotamia as most scholars believe but was in the northern part of the region. The first thing she notes is that the traditional connection between Babylon and Shinar comes primarily from the Tower of Babel. It is believed that since the names “Babel” and “Babylon” are so similar then they must be the same. However, she notes the difference in meaning of each word. “Babylon” means “gate of god” while “Babel” means “confuse” (Habermehl 2011, pp. 30–31). Therefore, the names actually do not have the connection that so many assume, having a completely different linguistic origin.

Shinar would have had to have been located somewhere besides southern Mesopotamia.

Second, Habermehl argues that there are geological difficulties with placing Shinar (and the Tower of Babel) in southern Mesopotamia. She notes that there is an important geological feature running east-west from the Euphrates to the Tigris north of Baghdad. From a creationist perspective this geological feature is believed to have been the ancient shoreline where the ocean level would have been immediately after the Flood but before the onset of the Ice Age. If this argument is true, then southern Mesopotamia would have been underwater during the building of the Tower of Babel (Habermehl 2011, pp. 31–33). Quite simply, Shinar would have had to have been located somewhere besides southern Mesopotamia where so many scholars have placed the country.

Habermehl argues that the name Shinar appears in the name of a mountain range in northern Mesopotamia, the Sinjar Mountains. Interestingly the names Sinjar, Shinar, and Sanhar are all variants of the same name (Habermehl 2011, p. 25). If Habermehl is correct and we place Shinar in northern Mesopotamia, would this help us in correctly identifying Amraphel? Sadly, since there is so little historical information available on the politics of the region around the Sinjar Mountains, we cannot know which city in this region Amraphel would have come from. No king lists from this area have been found. Even if Habermehl is correct in placing Shinar in the north (and she very well may be), we have no way to learn more about Amraphel, king of Shinar.

The second king was Arioch of Ellasar. Aalders (1981, p. 282) and Leupold (1942, p. 447) believe that Ellasar can be identified with the city of Larsa on the lower Euphrates. Leupold even makes the suggestion that he is King Rim-Sin of Larsa who ascended the throne in 2098 BC (he dates the expedition of Genesis 14 to 2088 BC). However, this identification is not accepted by all. Hamilton says that phonetically it is impossible to equate Ellasar with Larsa (Hamilton 1990, p. 400). Wenham says that the equation to Larsa is largely based on a misreading of the name of one of its kings, Warad-Sin, as Eri-aku (Arioch) (Wenham 1987, p. 308). Even so, Henry Morris, although not specifying Larsa, does say that Ellasar was a leading tribe in southern Babylonia (Morris 1976, p. 312).

However, not all scholars agree with this and some feel that Ellasar was located in northern Mesopotamia (Aalders 1981, p. 282). Kitchen (2003, p. 320) says

Arioch bears a name well attested in the Mari archive as Arriwuk/Arriyuk in the early second millennium and Arriukki at Nuzi (mid-second millennium). So he may be north Mesopotamian.

Wenham (1987, p. 308) notes that the name Ellasar is currently uncertain. But he cannot help giving us a theory. He says:

It may possibly be a town mentioned in the Mari texts, Ilanzura, between Carchemish and Harran, or less likely, an abbreviation of Til-Asurri on the Euphrates. A better suggestion . . . identifies Ellasar with eastern Asia Minor on the basis of etymology, versional support, and intrinsic probability. Ellasar could be related to . . . “hazelnuts,” for which Pontus, on the southern coast of the Black Sea, was famous. The Vulgate and Symmachus translate it “Pontus,” while the Genesis Apocryphon says “Cappadocia.” (Wenham 1987, p. 308)

Hamilton also believes that Ilansura located between Carchemish and Harran and Alsi/Alsiya in northern Mesopotamia are possibilities (Hamilton 1990, p. 400). So the current consensus seems to place Ellasar somewhere either in northern Mesopotamia or possibly as far north as northern Anatolia (modern Turkey).

The third king is Kedorlaomer of Elam. His name is definitely Elamite. There were many kings whose names began with something that is equivalent to “kedor.” The last part of the name is of an Elamite goddess “Lagamer” (Aalders 1981, pp. 282–283; Hamilton 1990, p. 399; Wenham 1987, p. 308). However, no concrete information has been discovered for this king (Aalders 1981, pp. 282–283; Hamilton 1990, p. 399; Wenham 1987, p. 308). Hamilton (1990, p. 399) notes that a list that identifies 40 kings of Elam during the Middle and Late Bronze Ages has no king by this name.

Kitchen (2003, p. 321) says

it is only in this particular period (2000–1700) that the eastern realm of Elam intervened extensively in the politics of Mesopotamia—with its armies—and sent its envoys far west into Syria to Qatna.

However, Kitchen is clearly wrong in this regard as Walther Hinz (1971, pp. 645, 647) notes that there are records of Elamite attacks on Mesopotamia in the Sumerian King List during the Early Dynastic period (although there is no mention of Elamite armies going as far as Syria in this early period). The records note that an Elamite king conquered Ur and that he was the founder of a dynasty of three Elamite kings. However, the king’s name is not recorded. Hinz notes that only the first syllable of the third king’s name is given. He says

[t]here was thus at this early date a powerful Elamite kingdom of Awan which was able to exercise authority over Mesopotamia for some considerable time.

Tidal king of Goiim is the fourth and last ruler to examine. “King of Goiim” is translated as “king of the nations.” Aalders notes that scholars have suggested that perhaps he was a “vagabond king” who was able to win over various tribes and provinces and was thus called “king of the nations” (Aalders 1981, p. 283). Leupold (1942, p. 448) says that if “Goyim” (another spelling of “Goiim”) means “nations” then Tidal was the head of a mixed group of people composed of different nationalities. He thinks “Goyim” may be another way of writing Guti who were a people of the Upper Zab. It was the Guti who invaded and conquered the Akkadian Empire.

Kitchen (2003, p. 320), Hamilton (1990, p. 400) and Wenham (1987, p. 308) think that Tidal is an early Hittite name, Tudkhalia.

[H]is title is a fair equivalent of the “paramount chiefs,” ruba’um rabium, known in Anatolia in the twentieth–nineteenth centuries, or as chief of warrior groups like the Umman-manda (Kitchen 2003, p. 320).

This Hittite name is found among the kings of the Hittites during the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, and it is even the name of a private person in Cappadocia during the Middle Bronze Age. Hamilton notes the connection between the Hebrew tid’al and Hittite Tudhalia “is evidenced by the Ugaritic spelling of the Hittite royal name as tdgl.” He continues, however,

That Tidal is named as king of Goiim (lit. “nations”) is perplexing. The term is deliberately vague, and is reminiscent of the phrase Umman-Manda (lit. “much people”), which was used later in cuneiform texts to describe the hordes of the northern and warlike Cimmerians and Scythians (Hamilton 1990, p. 400).

Wenham notes that one scholar compares the Greek Pamphylia “rich in peoples” with the Hebrew word “Goiim” and thinks that the Hittites are the correct identification (Wenham 1987, pp. 308–309). However, similar to Hamilton, Wenham believes that it is unlikely “Goiim” is another name for the Hittites. He thinks that it may be a Hebrew equivalent of the Akkadian Umman-Manda (Manda people) who were barbarian invaders of Mesopotamia starting in the last part of the Early Bronze Age. They are even sometimes associated with the Elamites which makes sense in the context of Genesis 14 (Wenham 1987, p. 308). Other possibilities could be a group or federation of Indo-European nations (Hittite and Luvian). It seems that most scholars tend to place Tidal and his “nations” in the Anatolian region. However, we know very little about the political history of this region during the Early Bronze Age, so discovering who Tidal actually was currently eludes us.

One will notice that the precise identification of these kings is currently very difficult to know. There is a debate about the location of two of the four nations that participated in the Genesis 14 raid: Shinar and Ellasar. The third nation, Elam, is identified but the names of her kings in the Early Dynastic period are lost. Although the records do show that at least one Elamite king invaded southern Mesopotamia we do not know if any other kings also attempted and succeeded in creating an Elamite empire. Lastly, Tidal king of Goiim seems most likely to be identified with a group or groups of people in the Anatolian region. Sadly, we know very little about the political and even ethnic makeup of this region during this early period (Bryce 1998, p. 13). One of the few political events that we do know of is of a group of 17 local rulers rebelling against Naram-Sin, whose empire (Akkad) extended into central Anatolia (Bryce 1998, p. 9). It is known that Anatolia did have different people groups existing side-by-side during the Early Bronze Age including the Hattians and various Indo-European groups (Bryce 1998, pp. 10–14). So it is realistic that Tidal may have united many of these groups and local rulers and ruled them as “king of the nations.”

Furthermore, the present lack of direct evidence concerning these kings in the archaeological record does not mean that they never existed. First, prior to the discovery of the Ebla archive, Early Bronze Age Syria was believed to have been an illiterate region with no great civilization because absolutely no documents had been discovered from this area (Astour 1992, p. 3). However, discovery of the Ebla archive proved ancient Syria was a literate region with a very organized and powerful empire. Second, Aalders (1981, p. 283) makes an excellent point when considering the historicity of the kings of the plain in Genesis 14. He notes that it is unlikely that they are the product of some later Jewish fantasy. “The name of the king of Bela (Zoar) is missing. Certainly, if all of these names were fictional, there would be no reason for leaving one name out.” This is an excellent point and can be extended to the kings outside of Palestine. If Moses was making up the kings of Genesis 14, why would he leave one of them unnamed? There is no reason to think that the names of any of the Genesis 14 kings were imagined. In fact, the information that we know about the four kings discussed shows that this event took place during a period that a coalition of kings could exist and that the Early Dynastic Period is a legitimate background for the Genesis 14 episode to have taken place. Kitchen (2003, p. 320) makes a good point:

Thus the personal names fit the regions they ruled and correspond with real names and known name types, even if the individuals are not yet identified in external sources. This is hardly surprising, given the incompleteness of data for most regions in the ancient Near East for the third, and much of the early second, millennia; even the great Mari archive covers only about fifty to seventy years.

Quite simply, the events discussed in Genesis 14 agree with the conclusions mentioned earlier that Abraham lived during the Early Dynastic Period. A group of kings in this chapter could not have occurred during the years of the Akkadian Empire. The dating of the Ebla archive to the Early Dynastic Period and the evidence that Genesis 14 conforms very well to the same period simply point to the Early Dynastic Period as the Mesopotamian background for the life of Abraham.

Sodom and Gomorrah

There is one last topic to discuss briefly, and that is the identification of Sodom and Gomorrah. Earlier in this article it was noted that Freedman (1978) identified five sites on the east side of the Dead Sea as the Cities of the Plain. Although his conclusions have been rejected by many, the discussion doesn’t simply end there. There are Christian scholars who believe that the same cities that Freedman identified were, in fact, the Cities of the Plain.

Bryant Wood, archaeologist with the Associates of Biblical Research, and William Shea both believe that these cities are to be identified as the infamous cities that were destroyed by God. Wood identifies the sites as: 1) Bab edh-Dhra as Sodom; 2) Numeira as Gomorrah; 3) the site of Safi as Zoar; 4) and the sites of Feifa and Khanazir with Admah and Zeboiim (Wood 1999, pp. 67–69).

A short summary of the evidence that Wood and Shea use to identify these sites as the famous Cities of the Plain follows. All of these sites are dated to the Early Bronze Age (Shea 1988, pp. 12, 14), and the name of Numeira is linguistically tied to the name of Gomorrah (Shea 1988, p. 17; Wood 1999, p. 69).13 Interestingly, both Bab edh-Dhra and Numeira seem to have had a very close relationship, as the Bible implies, between Sodom and Gomorrah (Wood 1999, p. 70).14

The Bible notes that there were two traumatic events that took place at Sodom and Gomorrah. The first is recorded in Genesis 14 and the second in chapter 19. There were two destructions at both of these sites (Shea 1988, p. 16; Wood 1999, pp. 70–72). (Although the Bible does not say that the kings in Genesis 14 destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah Shea (1988, p. 17) notes “[i]t was common practice of ancient kings to burn the cities they conquered after they looted them.” It would have been natural for this to have happened to Sodom and Gomorrah, as well.

Wood notes that the last destruction at Bab edh-Dhra began on the roofs of the buildings. This is consistent with the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah in the Bible (Shea 1988, pp. 19–20; Wood 1999, pp. 75–78). The interval between these two destructions is about 20 years, which fits the biblical data of the interval being between 14 and 24 years (Shea 1988, pp. 18–19; Wood 1999, p. 72). Shea (1988, p. 21) and Wood (1999, p. 78) and also note that the destruction of the cities can be set in the late spring or summer (see Genesis 18:10, 14). Shea (1988, p. 14) summarizes the evidence at these sites well when he says:

From their location, their time of occupation, the nature of their destruction, and their abandonment without further occupation, it is already evident that these five towns fit reasonably well with the profile of the five Cities of the Plain in the Bible.

Although this is only a very short summary of the evidence concerning Sodom and Gomorrah it was important to discuss it since earlier in this article it was shown that many scholars have rejected this identification. However, these criticisms presented are not as strong as some may think. Bimson presented four criticisms. First, the Cities of the Plain were not mentioned in the Ebla Tablets. Second, the identification of Sodom and Gomorrah as these particular cities during the Early Bronze Age has a problem since no Early Bronze Age remains have been discovered in the Negev which was central to the Patriarchal narratives. Third, the evidence must show that four of the Early Bronze Age sites must have fallen at the same time. Fourth, that biblical chronology cannot be stretched back that far into the Early Bronze Age (2300 BC).

First, the cities of Sodom and Admah are listed in an Ebla atlas (Shea 1983). Although not all the cities are mentioned it is a great find that at least two of them were. It must also be mentioned that just because the other three are not listed does not mean they didn’t exist at that time. Second, the criticism concerning the Negev holds no weight at all. The Negev is mentioned in Genesis 12:9; 13:1; 20:1; and 24:62. These verses do not require any form of permanent settlements. There is a good chance that the region at the time of the patriarchs was mostly filled with nomadic people so any kind of archaeological evidence from the Early Bronze Age may not exist.

Third, archaeological evidence cannot tell us the exact years when a city was destroyed unless there is some document or tablet which dates that destruction to a historical event. No such documents or tablets have been discovered in the layers of these five sites. However, it is reasonable to conclude using the evidence presented by Wood and Shea that these five sites are, in fact, the Cities of the Plain. Fourth, the argument that biblical chronology cannot be stretched back to the Early Bronze Age is based upon the validity of the standard chronology. As noted throughout this paper the standard chronology of the ancient world has been criticized and, as a result, biblical chronology can, in fact, reach back into the Early Bronze Age because the Early Bronze Age chronology has been brought down to the patriarchal period.

Conclusion: The Mesopotamian Background of the Narrative of Abraham

This article began with the goal to discover the Mesopotamian background of the life of Abraham. It was noted that he is usually dated to the Middle Bronze Age which was the Mesopotamian equivalent to the Ur III and Isin-Larsa periods. However, with the chronology of the ancient world coming under scrutiny it is only natural that the historical background of Abraham must be redated.

Studies in ancient chronology now show that the life of Abraham was concurrent with the Early Dynastic Period in Mesopotamia, the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdoms in Egypt, and the Ebla Empire in Syria. The evidence related to Genesis 14 and Sodom and Gomorrah also supports the conclusion that Abraham lived during the Early Bronze Age/Early Dynastic Period. Understanding that Abraham lived during the Early Bronze Age/Early Dynastic Period allows us to more clearly understand the cultural background of the Genesis narratives. It also provides creationist historians and archaeologists with an anchor point for studying the rich pre-Abrahamic period of the Ancient Near East.

References

Aalders, G. C. 1981. Genesis: Volume I. Translated by William Heynen. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

Albright, W. F. 1963. The biblical period from Abraham to Ezra: An historical survey. New York, New York: Harper & Row.

Archer, G. L. 2007. A survey of Old Testament introduction, revised and expanded. Chicago, Illinois: Moody Publishers.

Archi, A. 1997. Ebla texts. In The Oxford encyclopedia of archaeology in the Near East, vol. 2, ed. E. M. Meyers, pp. 184–186. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Ashton, J. and D. Down. 2006. Unwrapping the pharaohs: How Egyptian archaeology confirms the biblical timeline. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Astour, M. C. 1992. An outline of the history of Ebla (part 1). In Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla archives and Eblaite language, vol. 3, eds. C. H. Gordon and G. A. Rendsburg, pp. 3–82. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Astour, M. C. 2002. A reconstruction of the history of Ebla (part 2). In Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla archives and Eblaite language, vol. 4, eds. C. H. Gordon and G. A. Rendsburg, pp. 57–195. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Bermant, C. and M. Weitzman. 1979. Ebla: A Revelation in Archaeology. New York, New York: Times Books.

Bimson, J. J. 1980. Archaeological data and the dating of the patriarchs. In Essays on the Patriarchal Narratives, eds. A. R. Millard and D. J. Wiseman, pp. 59–92. Leicester, United Kingdom: IVP. Retrieved from http://www. biblicalstudies.org.uk/epn_3_bimson.html.

Bright, J. 1981. A history of Israel, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pennysylvania: Westminster Press.

Bryce, T. 1998. The kingdom of the Hittites. Oxford, USA: Clarendon Press.

Crawford, H. 1997. Adab. In The Oxford encyclopedia of archaeology in the Near East, vol. 1, ed. E. M. Meyers, pp. 14–15. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Freedman, D. N. 1978. The real story of the Ebla tablets: Ebla and the Cities of the Plain. Biblical Archaeologist 41, no. 4:143–164.

Gelb, I. J. 1977. Thoughts about Ibla: A preliminary evaluation. Syro-Mesopotamian Studies 1, no. 1:1–30.

Gelb, I. J. 1981. Ebla and the Kish civilization. In La Lingua di Ebla, ed. L. Cagni, pp. 9–73. Naples.

Habermehl, A. 2011. Where in the world is the Tower of Babel? Answers Research Journal 4:25–53. Retrieved from http://www.answersingenesis.org/articles/arj/v4/n1/where-is-tower-babel.

Halley, H. H. 1965. Halley’s Bible handbook. 24th ed. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. Hamilton, V. P. 1990. Genesis 1-17. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdsmans.

Hansen, D. P. 1997. Kish. In The Oxford encyclopedia of archaeology in the Near East, vol. 3, ed. E. M. Meyers, pp. 298–300. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Hinz, W. 1971. Persia c. 2400–1800 B.C. In The Cambridge ancient history, vol. 1, part 2, eds. I. E. S. Edwards, C. J. Gadd, and N. G. L. Hammond, pp. 644–680. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hoerth, A. J. 1998. Archaeology and the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books.

James, P., N. Kokkinos, R. Morkot, J. Frankish, I. J. Thorpe and C. Renfrew. 1991. Centuries of darkness. (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Jastrow, M. 1915. The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria: Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature. Philadelphia, Pennysylvania: J. B. Lippincott Co.

Jones, F. N. 2005. The chronology of the Old Testament. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

King, L. W. 1915. A history of Babylon: From the foundation of the monarchy to the Persian conquest. London, United Kingdom: Chatto & Windus.

Kitchen, K. 2003. On the reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

LaSor, W. S., D. A. Hubbard, and F. W. Bush. 1996. Old Testament survey: The message, form, and background of the Old Testament, 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans.

Leupold, H. C. 1942. Exposition of Genesis, vol. I. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.

Margueron, J-C. 1997. Mari. In The Oxford encyclopedia of archaeology in the Near East, vol. 3, ed. E. M. Meyers, pp. 413–417. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Martin, H. P. 1997. Fara. In The Oxford encyclopedia of archaeology in the Near East, vol. 2, ed. E. M. Meyers, pp. 301–303. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Matthiae, P. 1977. Ebla: An empire rediscovered. Trans. C. Holme. 1981. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company.

Matthiae, P. 1997. Ebla. In The Oxford encyclopedia of archaeology in the Near East, vol. 2, ed. E. M. Meyers, pp. 180–183. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

McClellan, Matt. 2011. Ancient Egyptian chronology and the book of Genesis. Answers Research Journal 4:127–159. Retrieved from https://www.answersingenesis.org/articles/arj/v4/n1/egyptian-chronology-genesis.

Morris, H. M. 1976. The Genesis record. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House.

Petrie, W. M. F. 1911. Egypt and Israel. New York, New York: E. S. Gorham.

Pettinato, G. 1981. The archives of Ebla: An empire inscribed in clay. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company.

Pettinato, G. 1986. Ebla: A new look at history. Trans. C. F. Richardson. 1991. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press.

Postgate, J. N. 1997. Abu Salabikh. In The Oxford encyclopedia of archaeology in the Near East, vol. 1, ed. E. M. Meyers, pp. 9–10. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Ray, P. J. Jr. 2007. The duration of the Israelite sojourn in Egypt. Bible and Spade 20, no. 3:85–96.

Rogers, R. W. 1915. A history of Babylonia and Assyria, vol. 2. New York, New York: The Abingdon Press.

Rooker, M. F. 2003. Dating of the patriarchal age: The contribution of ancient Near Eastern texts. In Giving the sense: Understanding and using Old Testament historical texts, eds. D. M Howard Jr. and M. A. Grisanti, pp. 217–235. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications.

Roux, G. 1992. Ancient Iraq, 3rd ed. New York, New York: Penguin Books.

Sayce, A. H. 1894. Primer of Assyriology. New York, New York: Fleming H. Revell Company.

Shea, W. H. 1983. Two Palestinian segments from the Eblaite geographical atlas. In The Word of the Lord shall go forth, eds. C. L. Meyers and M. O’Connor, pp. 589–612. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

Shea, W. H. 1988 Numeirah. Archaeology and Biblical Research 1, no. 4:12–23.

Wenham, G. J. 1987. Genesis 1–15. Waco, Texas: Word Books.

Winckler, H. 1907. The history of Babylonia and Assyria. Trans. J. A. Craig. New York, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Wood, B. G. 1999. Digging up the sin cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. Bible and Spade 12: 67-80. Retrieved from http://www.biblearchaeology.org/post/2008/04/the-discovery-of-the-sin-cities-of-sodom-and-gomorrah.aspx#Article.