The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

Native tradition contained in the Quito Manuscript does not support settlement of Peru in 2197/6 BC. Neither the primary author of the Manuscript, an anonymous cleric, nor Fernando de Montesinos, the editor, claims that Peru was settled 150 years after the Deluge by Noah. Montesinos claims in his introductory remarks that Peru was settled 340 years after the Deluge by the biblical figure Ophir, which is not a native tradition. The history of Peruvian rulers related in the Manuscript does not reflect sufficient passage of time to tie that history to a date as early as 2197/6 BC. When events described in the Manuscript are compared to external accounts of Peruvian history, clear linkages appear that place the time frame of the history in the Manuscript to a period starting near the birth of Christ and ending at the time of the Spanish conquest of Peru. The Manuscript was written from historical material collected from people who were not the original settlers of Peru. DNA evidence suggests the current indigenous population of Native Americans, including the Peruvians, came to the Americas in the first few centuries after the time of Christ.

Keywords: Americas, Clovis, Deluge, Dispersion, DNA, Flood, Masoretic, Native Americans, peopling, Peru, pre-Clovis, Quito Manuscript, Septuagint, settlement

Introduction

In their reply to my comments (Tweedy 2024a) on the series of papers titled “Chronological Framework of Ancient History”: Parts 1–5 (Griffith and White 2022a, 2022b, 2023a, 2023b, 2023c), Griffith and White (2024) made some good points in response, pointing out some of my technical errors, but they did not really refute my main points. I let my comments stand.

One particular issue that we disputed and that I would like to explore further is the settlement of Peru (Griffith and White 2022b, Duration 17). In their paper, they say,

Fernando Montesinos was a Spaniard who collected the songs and legends of the Indians of Peru and Ecuador in the sixteenth century. His record of these legends is called the Quito Manuscript. In it, he records the Peruvian oral tradition of their ancestors being led by Noah, called Viracocha, to colonize Peru in the distant past (Hylands [sic] 2010, 121) [citation in original].

We will introduce evidence contradicting this statement to the effect that:

- Fernando de Montesinos entered Peru in the seventeenth century, AD 1629, not the sixteenth.

- Montesinos did not collect the songs and legends of the Indians. The historical material in question was collected by the Bishop of Quito, López de Solís, from interviews with his native parishioners and was assembled into the Quito Manuscript by an anonymous cleric. By his own admission, Montesinos subsequently bought the Quito Manuscript at an auction in Lima.

- The pre-Incas and Incas, whose history the Quito Manuscript purports to convey, did not transmit their history strictly orally, or by songs and legends. They recorded their history using quipus, color-coded knotted strings. These were interpreted by amautas, pre-Incan and Incan sage-historians.

- Montesinos does not claim that Peru was settled 150 years after the Deluge by Noah but 340 years after the Deluge by Ophir. He disclaims that this information came from the amautas.

- Montesinos made many changes to the Quito Manuscript, including adding a brief introduction. This introductory material (three paragraphs) is unrelated to the Indian lore that follows.

- Noah is nowhere in the manuscript equated to Viracocha, the creator god of the pre-Incas and Incas. Viracocha is an image of the God of the universe, perhaps brought to Peru by original settlers before the Indians.

- The Quito Manuscript refers to the distant past, but internal and external evidence shows that the past it portrays goes back only so far as the birth of Christ, give or take a few centuries.

- DNA evidence supports this interpretation of the Quito Manuscript.

We will start by discussing briefly the Quito Manuscript and its provenance and then analyze the Manuscript’s content. The account of 93 pre-Incan rulers found in the Manuscript, if their number can be trusted, could support a long history, but not so long as to tie sixteenth or seventeenth century Peruvians to the time of the settlement of Peru posited by Griffith and White (2022b, Duration 17), viz.: 2197/6 BC. Chronological data support a date near the birth of Christ from which the events in the Quito Manuscript can be counted. Chapters 2 and 3 of the Manuscript provide much evidence that the surrounding countryside near Cusco was densely populated by the time the Ayar brothers, well documented predecessors of the Incas, settled in Cusco.

Griffith and White (2022b, Duration 17) also make a statement concerning the creator god of the pre-Incas and Incas, who is named Viracocha (subject to multiple spellings throughout Andean chronicles). They say that Noah was called Viracocha. Actually, we will see that the anonymous author of the original work clearly distinguishes Noah from Noah’s creator God, the latter being called Illatici Huira Cocha (Viracocha) throughout the Manuscript.

Consistent with a hypothesized timeline for the history related in the Manuscript starting near the birth of Christ is the proposal that the Americas were settled in antiquity twice as put forth by Jeanson (2021, 133–154). A very brief overview will be given of both the conventional view of the settlement of the Americas followed by a creationist alternative that indicates a two wave settlement under a much shorter biblical timeline. Under this scenario, we posit an initial settlement of the Americas at an unknown time after the Tower incident. Just after the time of Christ, a second wave of resettlement arrived on American soil, and these people seem to have been extremely successful, completely replacing or absorbing their predecessors by the time of European exploration. These newcomers would be the ancestors of the current population of American Indians, including the Peruvians. The main evidence for this is DNA analysis.

Provenance of the Quito Manuscript

In 1643, after 14 to 15 years living in and traveling throughout Peru, a Spanish secular priest named Fernando de Montesinos began a return voyage to Spain with five volumes of writings about Andean culture and history (Hyland 2010, 1, 13). The total work was at first named Memorias antiguas i nuevas del Pirú. Through time, the work took on other titles including Memorias antiguas historiales y policicos del Piru, Memorias antiguas historiales del Piru, or simply Memorias historiales or Memorias antiguas.

Book 2 of the five volumes is called the Quito Manuscript. After a brief introduction displaying the editor’s (Montesinos) academic knowledge of Genesis history, the Manuscript contains a synopsis of traditional Andean history covering both pre-Incan and Incan rulers written by an anonymous author but obviously modified by Montesinos (see below). The Spanish text has been translated into English a number of times, such as by Jiménez de la Espada (Montesinos 1882) and Means (Montesinos 1920). Means used the edition of the manuscript edited by Jiménez de la Espada. Hyland (2010) went to great lengths to find the most ancient manuscripts of the Memorias historiales in order to restore the manuscripts as close as possible to their original states using text critical techniques, but she did not provide a new translation.

Major and minor differences exist between versions of the Quito Manuscript. A version called the Madrid manuscript dated to 1642 is completely lost, but a copy of the first two books of Memorias historiales was made from that manuscript by a single hand-copyist resulting in the Seville manuscript. The original Seville manuscript also is lost, but copies of it remain. Between the Seville manuscript dated 1644 and the Merced manuscript dated 1645, Montesinos made many changes outlined by Hyland (2010, chapter 8). Among these, two of the 93 pre-Incan kings were dropped from the Merced text, which Hyland restored in her recension (Hyland 2010, 82).

We know that Montesinos is not the original author of Book 2 of the Memorias historiales (the Quito Manuscript) for these reasons.

- Hyland (2010, 63) states, “In Book I [of Memorias historiales], Montesinos himself stated that his indigenous history came from a manuscript about ‘Peru and its emperors’ that he purchased at an auction in Lima, and written by a resident of Quito.” Means (Montesinos 1920, 1ff footnote 1) provides an English translation of the respective language from Book 1.

- Book 2, except for the three paragraph introduction, is in a completely different style and vocabulary from the rest of Montesinos’ work as witnessed by the other four volumes in the Memorias historiales.

- Book 2 reflects personal attitudes different from Montesinos’ as demonstrated elsewhere in Memorias historiales. From Hyland (2010, 7, 61):

The author of the Quito manuscript, in contrast [to Montesinos], repeatedly lauded Inca culture and government, portraying the Inca emperors as wise kings who ruled according to natural law . . . Whereas the narrator of Book II emphasized the wisdom, learning and true religion of the Peruvian rulers, while recognizing the alleged decadence of some of the Andean peoples, Montesinos rejected any such distinction, viewing all native peoples in a very negative light. - The text contains numerous grammatical errors in the Spanish, such as disagreements between subject and verb respecting number, and both number and gender mismatches between nouns and adjectives (Hyland 2010, 61–62). For example, see Montesinos (1920, 11 note 1) where Means points out a gender disagreement. The author uses los cuales (translated “which” in masculine gender) instead of las cuales (feminine) to refer to the local lords’ daughters.

- The author is inconsistent in the use of Quechua names, indicating possibly a local Ecuadorian dialect as a native language for the author.

Book 2 is ascribed to this unknown writer who lived in Quito; hence, the name Quito Manuscript is commonly assigned to the contents of Book 2. Hyland (2010, 66) describes the author in this way:

In any event, whichever long-time resident of Quito composed this account, it is a very pro-Inca text, concerned with legitimising [sic] Inca rule in the Andes. Presumably, therefore, it was written by an indigenous or mestizo person, such as Lobato [Diego Lobato de Sosa Yarucpalla], with close ties to Inca rule in the Quito area.

Lobato de Sosa (Hyland 2010, 64–65) was a mestizo Catholic priest whose mother had been one of Atahuallpa’s principal wives (Atahuallpa was the last Incan emperor), so Lobato would have had access to the amautas (sage-historians) associated with Incan royalty, which would be essential. Those men would be the only people alive who could interpret the quipus with which the Incas and their predecessors recorded their history. The amautas that interpreted the quipus were called khipu kamayuqkuna (“quipu specialists”) in Quechua, the native Incan spoken language that was given a Romanized rendering after colonization. Their job was to memorize additional details to “flesh out” the total story each quipu represented (Pärssinen 1992, 26–51). The Quito Manuscript relates how the pre-Incan peoples lost their script and resorted to quipus for record keeping (Montesinos 1920, 58–63).

Lobato would have worked under the Bishop of Quito, who is credited with making the inquiries among the Indians to know their history. This conjecture that Lobato could be the author of the Manuscript makes great sense. I doubt that an Ecuadorian layperson would have provided as much biblical detail and even knowledge of the Masoretic and Old Greek translation/Septuagint texts, but that would not be surprising coming from a Catholic priest, albeit one with native background. That the historical materials were gathered by the Bishop is recognized by Montesinos himself in Book 1 of the Memorias historiales (see Montesinos 1920, 1ff note 1). This is also reported by Carmona Moreno (1993).

Montesinos appears to have made revisions and margin notes and to have rewritten the Memorias historiales entirely between 1644 and 1645 (Hyland 2010, chapter 8). Apparently, his margin notes were eventually included in the text itself (Hyland 2010, 84). Hyland details the changes Montesinos made to Book 2 during this period, especially noting that he made major changes to the first three paragraphs, which is where the interpretation of the Dispersion and settlement of South America by Ophir are proclaimed (more below). Hyland states, “I suspect that the first three paragraphs of Book II represent Montesinos’s [sic] own composition; the text that he copied from the anonymous source apparently begins with the fourth paragraph” (Hyland 2010, 80). These first three paragraphs contain the essence of what Griffith and White say supports their thesis (Griffith and White 2022b, Duration 17). The data relied on by Griffith and White appear to have no support in native lore, and they say something different from what Griffith and White claim regarding the timing and manner of the settlement of Peru (see below).

Analysis of the Quito Manuscript

The Quito Manuscript fails to provide a reliable witness to historical facts in many ways. Its internal chronologies are inconsistent with each other and with external data. Anachronisms abound. Critical claims contradict one another. Logical and textual errors are rampant. Hence, very few dates derived directly from the Quito Manuscript are reliable.

Chronologies in or Concerning the Quito Manuscript

The Manuscript has two contradictory sets of chronological data embedded in it, most of which conventional analysts have completely disregarded in favor of external data. We detect four distinct sets of chronological data in or concerning the Manuscript, the two internal sets based on the following text from Chapter 13 of the Manuscript (Hyland 2010, 137; Montesinos 1920, 57):

The amautas say that in the second year of the reign of Manco Capac the 4th sun of Creation was fulfilled, which is four thousand years, a little less, and 20,900 [sic; means translates as 2,900] and so on after the general flood, and counting year by year, it comes to be the first of the birth of Christ, our Lord . . . According to the account of these Peruvians, forty-three years were missing for the complete fulfillment of the four suns, and it agrees, not without admiration, with the account of the 70 interpreters [reference to the Old Greek translation/Septuagint] and with that followed by the Roman Church, which says that the Divine Word was born from the womb of the Virgin 2,950 years after the flood.

The first chronology is based on a time period called a “sun,” equating the same to 1,000 years of time, the first “sun” starting with Creation. Let us call this the “suns” chronology. Using the above quote, we can assign a figure of “zero” to the Incarnation tying the event of Christ’s birth to 43 years before the end of the fourth Sun. That sets the end of the fourth Sun at AD 43 and the Creation 4,000 years earlier at c. 3957 BC (ignoring two aspects: no year “zero” in our current system, and Jesus’ birth assigned analytically to c. 4 BC). Using the figure of the Deluge happening 340 years before the end of the second Sun places the Deluge in (–3957 + 2000 –340 =) 2297 BC and Ophir’s settlement of the Americas 340 years later in 1957 BC at the beginning of the third Sun.

While pointing out that “suns” were treated as millennia in other Andean chronicles, Hyland (2010, 76, 95) notes at least one opinion (Ponce Sanguinés 1999) that a “sun” is not millennial but much shorter. One possible perception here is that in an attempt to establish the antiquity of Peruvian rule, the anonymous author may have taken events from a much shorter time period and stretched them out over more than five millennial “suns.” Means (Montesinos 1920, xli) points out that the suns chronology is completely unworkable. See the third chronology below.

A second chronology is represented by events tied to the date of the Deluge in 2950 BC as stated in the quote above, a date in conflict with that derived from the “suns” (2297 BC) in the introduction, and a date unfamiliar to this author. Let us call this second chronology the “Deluge” chronology. We note that since the writing of the Manuscript occurred during the century following the Reformation and that Luther preferred the Masoretic text for his translation of the Old Testament into German (Witherington 2017), reference to the Old Greek translation/Septuagint in connection with the Roman Church at this time makes some sense even though Means (Montesinos 1920, 2 note 1) thinks Montesinos may refer to the Masoretic chronology in the introduction (see below).

Hyland (2010, 101) believes this date of 2950 BC for the Deluge was inserted by Montesinos, who states elsewhere in Memorias historiales that Creation occurred 1,000 years before the Deluge, putting Creation at 3950 BC. Coincidentally, the narrative states in another place that in the years of Titu Yupanqui Pachacuti, 3000 years had elapsed since the Deluge and that at the same time, the fourth “sun” of creation had been completed (Hyland 2010, 138; Montesinos 1920, 58). This narrative is in direct contradiction with the data recorded just one page earlier as quoted above, indicating a possible textual insertion by Montesinos.

A third chronology is reflected in Means commentary throughout his translation after he notes in the front material that the Deluge occurred c. 2200 BC (Montesinos 1920, xli). The origin of this date is unknown to this author. Based on this date, Means points out some absurdities by projecting “suns” into the future, arriving at AD 1800 as being in the lifetime of the last pre-Incan ruler. Means also makes a comment that he believes the introduction is based on a date of 4004 BC for Creation (Montesinos 1920, 2 note 1), indicating that he was at least acquainted with some Christian scholarship on this topic.

A fourth set of data can be derived from conventional archaeology, radiocarbon dating, and conventional history. Some of this is embedded in notes in Hyland’s textual analysis (Hyland 2010), Means’ translation (Montesinos 1920), Ponce Sanguinés’ archaeological studies (Ponce Sanguinés 1999), and many others. These data are completely inconsistent with all the internal data and only span about 1,000–1,100 years. The archaeological data associated with pre-Incan Peru have “recent” ages associated with them. Archaeological estimates for the beginning of the history in the Manuscript include c. AD 10 (Montesinos 1920, 55 Means’ footnote), c. AD 125 (for example, Montesinos 1920, Means’ Tables III and IV), and c. AD 400 (Ponce Sanguinés 1999; Szeminski 1995; Young-Sánchez 2009).

Based on the numbers given in various places, hugely divergent dates for various events are possible. For example, we observe that the “suns” chronology puts the first Peruvian ruler near the middle of the third Sun. According to the Manuscript, Sinchi Cozque, the fourth ruler of Peru, died after ruling 70 years (Hyland 2010, 127; Montesinos 1920, 28), at which time, 1,000 years had passed since the Deluge (Hyland 2010, 125; Montesinos 1920, 20). His death then would be c. 1297 BC on the “suns” chronology but 1950 BC on the “Deluge” chronology. Working backward using the spotty regnal periods quoted in the Manuscript, we find that the first ruler, Tupac Ayar Uchu (or Pirua Picari Manco) died c. 1447 BC on the “suns” chronology but c. 2100 BC on the “Deluge” chronology. I have marked significant dates assigned by these chronologies in the spreadsheet exhibit, which clearly shows these conflicts. See the1 notes for a key to the spreadsheet. All this shows the text to be unreliable history.

Montesinos’ Introduction

The introduction states that “two suns” (2,000 years) passed from Creation to the Deluge except for 340 years to complete the second Sun (Hyland 2010, 120; Montesinos 1920, 1–3). Means does not understand the biblical significance of this figure of 340 years as evidenced by his note on page 2 (Montesinos 1920, 2 note 1), indicating he is not totally familiar with Ussher’s Masoretic timeline (Ussher 1650). 340 years is the time from the start of the Deluge to Peleg’s death in 2008 BC on Ussher’s timeline. The relationship between the Flood, Peleg’s death, and the Dispersion was well established among Jews and Christians as early as AD 300–500 as testified in both the Seder Olam Rabbah (Jose ben Halafta 1998) and the Midrash Rabbah: Genesis (1983), both of which give the traditional Jewish time of the Dispersion as the year of Peleg’s death, 340 years after the Deluge according to the Masoretic text.

All these facts would be known to Montesinos and to the anonymous cleric who penned the bulk of the Manuscript but would not have been known by the amautas. It appears that this entire chronology could be simply a rehearsal of Christian scholarship produced by Montesinos and/or the anonymous author to establish biblical correspondence.

The biblical history cited in the introduction is completely divorced from the account of the original Peruvian rulers, quite as if the introduction were just tacked on at the beginning as Hyland suggests. In his introduction, Montesinos (1920, 2) explicitly contradicts the Indian lore in his hands, saying of the amautas, “But they erred . . .” That divorces the introduction completely from Indian lore. He then goes on to make the explicit claim that Peru was settled by Ophir 340 years after the Deluge, consistent with the death of Peleg on the Masoretic chronology. On the “suns” chronology, this calculates to a date for the settlement of Peru at 1957 BC at the beginning of the third Sun, and puts the date of settlement at 2610 BC on the Deluge chronology.

Ophir is noted in Genesis 10:30 and 1 Chronicles 1:23 as the eleventh of thirteen sons born to Joktan, a descendant of Shem. According to Montesinos’ own writings in Book 1 of Memorias historiales, Ophir had a fleet of ships which he used to populate much of the Americas (Hyland 2010, 36). In his introduction, Montesinos cites “Cedrenus2 notes and Philo3 notes in his Antiquities” as sources to back his claims (Hyland 2010, 120; Montesinos 1920, 3), sources that would not have been known to the amautas, and clear evidence of augmentation of the Manuscript by Montesinos.

The introduction refers to the origin of the Dispersion as “Armenia,” which was unknown as a place name until no earlier than c. 800–600 BC (Mallory and Adams 1997, 30), so the only way the amautas could have known the place name “Armenia” would be from the Spaniards, who came too late to influence the quipus. This reference to “Armenia” and the later reference to population issues in Armenia 150 years after the Deluge are both insertions by Montesinos with no basis in native lore. He says that “grave authors” (Hyland 2010, 120; Montesinos 1920, 3; or “great authors”) testify to the 150 year mark and that there is “no lack of [authors] who say” that Noah (not Viracocha, by the way) personally went about the earth making allotments for his sons and grandsons. The implication is that Montesinos is appealing to early western writers (that is, Cedrenus and Philo) to establish credibility, not to native sages (amautas). Beyond that, the idea that everyone cooperated to effect the Dispersion is a serious contradiction of Scripture. Genesis 11 is terse, but it states quite clearly that the Dispersion from Babel was caused by the confusion of languages, not population pressure.

Pre-Incan Traditional History

The Manuscript then describes 93 individuals who ruled in the Cusco area before the first Inca ruler rose to power, posited conventionally to have taken place c. AD 1100–1200. Being too voluminous to present here, I have summarized the history of these 93 individuals in the spreadsheet exhibit. If the introduction is included in the analysis, the Manuscript implicitly claims that the reigns of these 93 individuals span the time from 500–600 years after initial settlement by Ophir in c. 1957 BC to the beginning of Inca rule. This is hardly possible as will be shown. Sarmiento de Gamboa (1907) suggests the passage of 3,519 years after the “general flood” to the first Inca ruler. Using the Ussher Masoretic date of 2348/7 BC for the Flood would yield c. AD 1172 for the beginning of Incan rule, or c. AD 1222 using the suns chronology. The Flood chronology produces a date of c. AD 569, much too early.

The traditional material in the Manuscript starts with a retelling of the legend of the four Ayar brothers (Hyland 2010, 120–121; Montesinos 1920, 3–7). In this widely documented legend (see, for example, Betanzos 1996, Sarmiento De Gamboa 1907), four brothers, their wives, and four sisters arrived in Peru near Cusco. In many versions of this legend, this family group supernaturally emerged from caves. The oldest brother wanted to rule and started to impose his will. The youngest brother, not willing to submit, found ways to murder the elder two brothers and to drive off the third so that he could assume power. This one is recognized traditionally as the first ruler of Peru and is named Tupac Ayar Uchu, or Pirua Pacari Manco. No explanation is given as to how this account meshes with the biblical introduction except for a brief reference to Noah’s God (see below), which was probably inserted by the author or editor.

Moving forward into the reign of Manco Capac (Montesinos 1920, chapters 2–3), we see much evidence that the Ayar family moved into an area that was already heavily settled. Manco Capac, only the second ruler in the Ayar line, determined to subjugate all the people that surrounded Cusco, indicating previous settlement. Of significant note, the legend of the Ayar brothers is also told as the origin of the Incas as preserved by Spanish chronicler Sarmiento De Gamboa (1907). The parallels between the Manco Ccapac (two “c”s) related by Sarmiento De Gamboa and the Manco Capac (one “c”) related in the Quito Manuscript are extremely close; however, neither bears on a virgin settlement of Peru.

The text describes the in-place inhabitants around Cusco as already having lords, wizards, and their own gods of Fire and Mother Earth. That is, the locals were established, so the Ayar family could not have been first settlers, although the introduction allows that they could have post-dated original settlement by 500–600 years. In order to cement his leadership with these existing local lords, Manco was going to marry a daughter of each of those lords. However, this marriage treaty process was interrupted by a huge influx of foreign people looking for a place to settle. While the inhabitants seemed to believe that these people were created in the vicinity of the Andean highlands, the Manuscript (Montesinos 1920, 3, 12) claims all these foreigners appeared after having been transported from “Armenia.” As we have seen above, the amautas would never have used this place name. Means (Montesinos 1920, 14 note 2) points out that this migration, probably from the region of Ecuador, is historically accurate for a much later time than supposed. All this and more removes the narrative in the Quito Manuscript from a near Dispersion timeframe.

For the Quito Manuscript to have any bearing on Dispersion history, the issue is to show how the time from settlement to Inca rule was filled by 93 pre-Incan rulers and/or other history. Unfortunately, many of the kings in the Manuscript are not given regnal years, which makes exact calculation impossible. An issue is whether the given regnal years, or even the number of rulers cited, are accurate (Hyland 2010, 69–71). Let us take a less direct approach. If we take the designated rulers at face value, the question is, how much history can be covered by 93 reigns? Hyland (2010, 63) believes the king list covers “thousands of years” but makes no actual calculation. Even if we had a regnal years list, the results should be subject to a “reasonableness” check. For a check, let us turn to Jeanson (Jeanson 2021, 146), who estimates the date of the crossing by the Lenni-Lenâpé (Delaware) people from Asia to America at c. AD 200–900 based on a list of 98 historical tribal leaders, or approximately 1,100 to 1,800 years before present. Using that as a guide, we could estimate a similar time frame, or slightly briefer, to extend 93 rulers prior to AD 1100, the earliest date assigned to the first Inca ruler. The result indicates approximately 700 BC to AD 1 for the first king in the Manuscript.

If we cannot take all the names in the list as valid, then the history of the pre-Incan kings is even shorter, extending less into the past. Hyland (2010, 74–77) notes others who have interpreted the history in the Quito Manuscript with shortened king lists. Hiltunen (1999) and Hiltunen and McEwan (2004) did so and state that the Manuscript describes the literal history of the Wari Empire (AD 500–750), which seems exceedingly short for so many rulers, even after culling some out. For historical context, the Wari Empire, located north of Cusco and Lake Titicaca, lived in peaceful tension with the Tiwanaku empire to the south (Flannery and Marcus 2012). Both empires are said to have derived from the Moche culture.

Szeminski (1995) admitting only the first 65 rulers as legitimate and Ponce Sanguinés (1999) discarding the first 16 and last 28 rulers posit that the Quito Manuscript describes the Tiwanaku empire, c. AD 400–1100 by their reckoning. Young-Sánchez (2009) falls into this camp. Means also speculates a possible timeline based on a “revision” of the kings list (Montesinos 1920, Tables III and IV) and casts backward from the start of the Incan era, which he puts c. AD 1100, to arrive at c. AD 125 as the beginning point of the history in the Manuscript.

Means uses conventional archaeology and historical analysis to anchor Ayar Tacco Capac, thirteenth king in the list, at c. AD 300 based on the coastal invasions of the Chinú/Chinos (Montesinos 1920, 40 note). This would put the first ruler, Tupac Ayar Uchu (Pirua Pacari Manco) at c. 300 BC based on the average regnal years of the first 14 kings, which are probably exaggerated. Means (Montesinos 1920, 55 second note) uses conventional archaeology and radiocarbon dating to equate everything in chapters 10–13 to the Tiahuanaco (Tiwanaku) empire and assigns the dates to AD 110–1000, a little different from his own estimation in his tables. Chapters 14 and 15 of the Manuscript (Montesinos 1920, 59–67) describe the invasion of the highlands by strangers and the aftermath, occurring just before the rise of the Incas c. AD 1100–1200. Goldstein (2007) and Janusek (2008) describe much of this same history of Tiwanaku in this timeframe.

In his introduction, Montesinos ascribes to Peruvian amautas a statement that the Dispersion occurred during the last 340 years of the second Sun. He then contradicts the amautas to say more precisely that Ophir settled the Americas 340 years after the Deluge, which is about the time of Peleg’s death in 2008 BC on Ussher’s Masoretic timeline. He then asserts that peace reigned among the descendants of Ophir for 500 years by one reckoning, 600 years by another, after which divisions and strife led to the rise of rulers. This would cut out some of the missing history in the Manuscript, producing a date c. 1300 BC on the suns chronology for the beginning of the first king’s reign. That still leaves about 600 to 1,300 years that seem not to be covered by the reigns of ancient Peruvian rulers to stretch back to c. 1957 BC. To reach 2197/6 BC requires another 240 years.

Other Issues

Textual issues

The number of Peruvian kings named in the Manuscript is not uniform depending on text variant. Hyland’s text (Hyland 2010) mentions 93 pre-Inca kings, and this is echoed by Hiltunen (1999, Appendix 1). Means’ translation of the Jiménez de la Espada text names only 92 kings in the text; he only lists 90 in his chronological table (Montesinos 1920: xxxix–xli, Table II). The Jiménez de la Espada text includes both of the kings omitted from the Merced text but appears to have omitted Huanacauri, king number 42 according to both Hyland and Hiltunen.

Also, the text very often cites the ordinal number for a given king like this: “King X was the nth king of Peru,” but these numbers are not consistent. Huascar Titu is the fourteenth king in the both the Hyland and the Jiménez de la Espada texts as well as Means’ Table II, but the text states, “he was the twelfth Peruvian king” (Hyland 2010, 132; Montesinos 1920, 42). This discrepancy of two kings persists until we come to Amaro, who is the 87th king in the Hyland text and the 85th in Means’ Table II, but the text says, “Amaro, who was the eighty-third [king] . . .” (Hyland 2010, 141; Montesinos 1920, 66).

There are also numerous less significant errors that a reasonably careful author should have avoided. For instance, in one paragraph, Inti Capac Yupanqui is called the youngest son of Sinchi Cozqui Pachacuti, but just a few paragraphs later, he is called the oldest son of Sinchi Cozqui Pachacuti (Montesinos 1920, 20, 24). Very many regnal years are missing in all textual variants, but many of the regnal years appearing in both Hyland (2010) and Jiménez de la Espada (Montesinos 1920) are obviously exaggerated. Even in the last of the pre-Incan kings, successors have reigns as long as their fathers’ at 50 years and above. Reigns that long back to back would imply biblically long patriarchal lifespans in the second millennium after Christ.

Anachronisms haunt the Manuscript. Most historians assign “empire” status to the Incas starting with the successful defense of Cusco from the Chancas by Cusi Inca Yupanqui, which occurred in AD 1438 by conventional history (Hyland 2010; Shalley-Jensen 2017). Tellingly, the Manuscript assigns the defense of Cusco from the Chancas to the reign of Sinchi Cozque Pachacuti (king number 4), much, much earlier. Another anachronism is the account of the child who cried blood. See Means’ note starting on page 14 of Montesinos (1920, 14ff note).

Noah and Viracocha

Griffith and White (2022b, Duration 17) assert that when Noah went about the world settling people that Noah was called Viracocha by the Peruvians. That equation is not supported by the Quito Manuscript. The author of the Quito Manuscript clearly distinguishes the Patriarch Noah from Viracocha (Hyland 2010, 121; Montesinos 1920, 7). The god Viracocha formally is called Illatici Huira Cocha in Jimenez de la Espada’s text, and Yllatici Huiracocha in Hyland’s restored text (2010, 121), viz.: “. . . al Dios del Patriarca Noé y de sus desçendientes, ni tubo otros Dios sino al Criahdor del mundo, llamándole Yllatiçi Huiracocha.” Translation: “ . . the God of the Patriarch Noah and his descendants, nor did he have any other God but the Creator of the world, calling him Yllatici Huiracocha.” The author of the Manuscript obviously is referring to Noah as a human and to Viracocha as the “Creator of the world” and Noah’s God. This name Viracocha (Wiraqucha in Quechua) has caused much confusion to translators. The consensus among the Spaniards during and after the Incan conquest (Itier 2012) was that the name should be translated according to one of this god’s common epithets, Creator. A literal translation seems to be “sea foam” or “sea fat” (Dover, Seibold, and McDowell 1992). From various sources, Viracocha seems to be an image of the God of the Universe, but that is a whole different discussion.

Syncretism

The history in the Manuscript appears to have been inserted into a Judeo-Christian chronological framework to give it greater credibility. Hyland (2010, 97) refers to Montesinos’ language surrounding the origins and timing of the settling of Peru as “speculation,” implying that the descriptions in the Manuscript were tainted by a desire to tie the Incan rulers directly to the Bible. Syncretism was a popular tactic with the Spaniards to convert New World inhabitants to Christianity (Itier 2012), and perhaps the Quito Manuscript is an attempt at using syncretism to validate Incan history. All said, the Quito Manuscript is unreliable as a source of Dispersion history.

Settlement of the Americas

Interpretation of the Quito Manuscript regarding whose history is being described depends on when certain cultures settled the Americas. The Manuscript describes a culture that developed close to the birth of Christ, but can we rule out ancestry for this culture from the original settlers of the Americas, which could be tied to the Dispersion if we had more data? We can only answer that question partially. The key is in the evidence we have for two settlements of the Americas. After very briefly setting the stage regarding settlement of the Americas using conventional and creationist scenarios, we will discuss DNA evidence (Jeanson 2021, 133–154; Llamas et al. 2016) that the sixteenth and seventeenth century Peruvians were not the original settlers of Peru but were resettlers who arrived soon after the birth of Christ. Depending on when they came, all of the history in the Manuscript could be the re-settlers’, or only some of it. Perhaps one of the several “invasions” of the Andean highlands described in the Manuscript refers to the influx of a new people who were the first Indians to arrive in Peru.

Conventional scenario

Conventional scientists date the settling of the Americas by two peoples (Pitblado 2011). By conventional reckoning, the pre-Clovis people began arriving c. 20,000 years before present (YBP), and almost nothing is known about most of them; they left scant physical evidence of their existence. The Clovis people, identified by their unique “fluted point technology” (see, for example, Buvit et al. 2018; Ellis 2013; Goebel et al. 2013; Ives 2024), left a huge archaeological “footprint” across the Americas, first appearing in the record c. 14,000 YBP on the conventional timeline. Davis and Madsen (2020, 3) document the radiocarbon dating behind this timeline. Haynes (1982) and Potter et al. (2018) claim a date of 14,800 YBP. Before discovering evidence for those two peoples, conventional scientists believed that the Native American Indians were the first people to settle the Americas dating back only c. 4,000 YBP (for example, Braje et al. 2020, 2). With the discovery and conventional dating of the Clovis culture, they simply pushed back the arrival of Native Americans 10,000 years assuming current Indians to be descended from the Clovis people. These ideas collectively are referred to as the Clovis Paleoindian Tradition (CPT).

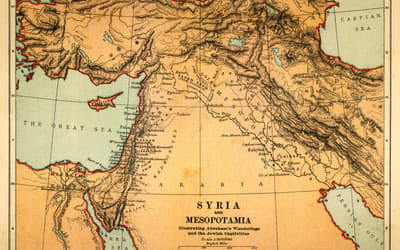

Two main migration paths of the Clovis people are proposed, a land route across Beringia (see Gargett 2012; National Park Service 2025) and south through the “ice free corridor” (“IFC”; see Antevs 1935; Johnston 1933; Upham 1895), and a coastal route (the coastal migration theory, or CMT) skirting the edge of Beringia (see, for example, Braje et al. 2020; Clark et al. 2022; Fladmark 1979; Yasinski 2022). Another possibility is that the Americas were settled originally from the sea (see Becerra-Valdivia and Higham 2020; Braje et al. 2020; Davis and Madsen 2020; Fladmark 1979; Llamas et al. 2016; Yasinski 2022). The sea crossing hypothesis is consistent with most Indian origin stories (Griffith and White 2024).

The creationist perspective is that both the pre-Clovis and Clovis peoples were among the original settlers of the Americas, possibly migrating soon or not too long after the Tower event. Contrary to current conventional thought, they were distinct from the current Native American peoples, which will be shown by DNA evidence below.

Biblical scenario

The creationist view is that the Americas were populated in two waves as well, but certainly on a much shorter timeline. The first wave of settlement could have been part of the original Dispersion from Babel, or possibly somewhat later. The typical scenario for the original settlement of the Americas as a part of the Dispersion (for example, Oard pers. comm. June 13, 2024) combines biblical and conventional elements. The story goes like this. Soon after the Babel uprising, people dispersed from Shinar, and at least one faction struck out to the northeast, crossed Asia, and found the Beringia land bridge. Their timing was such that they were not blocked by glaciers from reaching Beringia on the Asian side and arrived on the North American side during the Cordilleran/Laurentide glaciation in Alaska and Canada. The migrants were able to skirt the American ice via the IFC; otherwise, they would have been blocked out of the rest of the Americas in this scenario.

Using the Masoretic timeline, the migrants would probably have had to reach the Bering Strait land bridge c. 2150–1750 BC when the Oard model suggests the bridge might be available (Tweedy 2024b) based on glaciation and meltdown as the major causes of sea level change. On the Septuagint timeline, the dates would be c. 3100–2700 BC. Oard (2020) proposes an alternative hypothesis consistent with previous conventional thought that the elevation of Beringia has changed by tectonic events, making Beringia higher than current levels c. 300–400 years post Flood followed by depression. A sea crossing could have been made at any time, and settlers could have come from almost anywhere irrespective of glaciation. The second wave would have happened much later based on DNA evidence (see below), and these second-wave “resettlers” would be the ancestors of the current population of indigenous American Indians, including those in Peru. This second crossing had to be by sea since no land bridge would have been available.

DNA evidence

So when did settlers of America come on a biblical timeline? We probably cannot answer that question directly for the initial settlers. Any data tied to the current Native American population would be pertinent only if the current population had been the first wave settlers of the Americas and not second wave re-settlers. Original settlement by the current native population, however, is contradicted by Jeanson (2021, 133–154). His analysis of Y chromosome variations in Native American men addresses the dominant Q and C haplogroups. Some conventional scientists do not filter out haplogroup R1a from analysis of Native American DNA because it is linked to other R1a populations in places like Altai, Siberia (see, for example, Dulik et al. 2012; Lewis 2012; Zakharov et al. 2004). Dulik and Zakharov et al. also refer to mitochondrial DNA links. Jeanson’s analysis confirms that Native American men had an origin somewhere in central Asia, but based on a his Y chromosome “clock,” his data also infer that the current Native American population arrived in the Americas no sooner than the first few centuries following the birth of Christ.

This late resettlement is also indicated by the Lenni-Lenâpé (Delaware) tradition excerpted by Jeanson (2021, 145–146; after McCutchen 1993, 76), which states that the Lenni-Lenâpé ancestors “marched” across the icy ocean to Akomen, ostensibly America. Jeanson estimates the date of the crossing at c. AD 200–900 based on a list of 98 tribal leaders (Jeanson 2021, 146). These data come from the Walam Olum (translated “red record”), first published by Rafinesque (1836). While generally accepted as legitimate throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (see, for example, Brinton 1885), the work has come under frequent claims of being a hoax starting in the 1930s. Typical criticisms follow those of Jackson and Rose (2009) and Newman (2010). Rafinesque attributes the original document to a Moravian missionary named “Dr. Ward,” who was given the materials as a gift by a tribal historian in 1820. Attempts at identifying this individual have been inconclusive, and the original records were lost, according to Rafinesque. However, McCutchen (1993) evidently had access to some of the original prayer sticks from the contemporary Lenni-Lenâpé leadership in Oklahoma when doing his research on Lenni-Lenâpé history.

Rafinesque suggests that the legends put the crossing of the Lenni-Lenâpé from Asia c. 1600 BC. This date is contradicted by Jeanson’s DNA data and his historical analysis. This timeframe is also contradicted by conventional anthropology. The Walam Olum suggests that the Lenni-Lenâpé ancestors struggled for several generations of chiefs with the Mound People at Cahokia, near present day East St. Louis, Illinois. Conventional dates assigned to the Cahokia site are c. AD 1050–1350 (Munoz et al. 2014), are rather late to entertain a crossing from Siberia in 1600 BC.

We can make two observations. First, the Lenni-Lenâpé migration is irrelevant to a discussion of the Dispersion, which likely happened more than two thousand years earlier. The Lenni-Lenâpé were part of the second wave, or resettlement. Second, there would not have been a land bridge in the Lenni-Lenâpé timeframe. It appears that the Lenni-Lenâpé crossed somewhere (not actually identified) on a frozen sea: “On a wondrous sheet of ice all crossed the frozen sea at low tide in the narrows of the sea” (Jeanson 2021, 145; after McCutchen 1993, 76).

This resettlement of the Americas in the early years of the Christian era has obliterated any possibility of knowledge of the original settlers by means of DNA analysis. Any surviving original people (perhaps the pre-Clovis and Clovis peoples and others) would have lost their unique Y chromosome signature by being overwhelmed by the newcomers. This replacement was fast enough and complete enough not to be reflected in the Y chromosome tree. Consistent with Jeanson’s Y chromosome data, a study of mitochondrial DNA by Llamas et al. (2016) shows that the mitochondrial DNA lines extracted from very ancient (pre-Columbian) human remains in Colombia do not exist in modern data sets; that is, those lines are extinct. When they went extinct is difficult to tell with any precision, but all DNA traces of the original population of the Americas seem to be gone. Jeanson (pers. comm. February 20, 2025), however, citing external evidence, tends to dismiss DNA evidence from the deceased as unreliable.

If the DNA evidence of Jeanson (2021) in particular and also perhaps Llamas et al. (2016) is reliable, then the recorded history of the current Native American population, including the Peruvians, does not reflect in any way on what happened during the Dispersion or afterward for considerable time. The original settlement of the Americas probably happened at least two thousand years before the current Peruvians or any other existing Indian tribes ever trod on American shores. The only open question for the Quito Manuscript is one of timing. We do not know if all of the rulers described in the Manuscript were Indian or if some were pre-Indian. We do know that the current native Peruvians are Indian by DNA.

Conclusion

The Quito Manuscript is not credible as Dispersion history. The introduction (first three paragraphs) is probably the product of Montesinos based on his interpretation of Genesis vis-à-vis early Christian writings. The remainder appears to be the product of an anonymous author who desired to justify Incan rule by establishing its history in antiquity and by tying it to the Bible for added credibility. The conflicts between the various chronologies associated with the history and many other erroneous factors undermine any credibility. The kings list, when fact checked against external data, lacks 840 to 1,540 years of what is needed to tie its narrative to a settlement of Peru in 2197/6 BC. The traditional history of the Manuscript does not testify to who settled Peru first or when.

The Quito Manuscript may be fairly accurate at describing Andean rulers starting around the time of Christ, but one cannot tell within less than a few centuries either way when that might have been. Beyond that, the Americas probably were settled in two waves, one possibly on the heels of the Dispersion from Babel if not somewhat later, and one at a much later time. The DNA evidence of Jeanson (2021) and Llamas et al. (2016) indicates that the Native American Indians living in Peru in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries AD were descendants of re-settlers; they were not descendants of the original post-Babel settlers, who were invaded near the time of Christ and eventually replaced. The Quito Manuscript is certainly consistent with that narrative.

References

Antevs, Ernst. 1935. “The Spread of Aboriginal Man to North America.” Geographical Review 25, no. 2 (April): 302–309.

Becerra-Valdivia, Lorena, and Thomas Higham. 2020. “The Timing and Effect of the Earliest Human Arrivals in North America.” Nature 584, no. 7819 (6 August): 93–97.

Betanzos, Juan de. (1880) 1996. Narrative of the Incas. Translated and edited by Roland Hamilton and Dana Buchanan. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

Braje, Todd J., Jon M. Erlandson, Torben C. Rick, Loren Davis, Tom Dillehay, Daryl W. Fedje, Duane Froese, et al. 2020. “Fladmark + 40: What Have We Learned About a Potential Pacific Coast Peopling of the Americas?” American Antiquity 85, no. 1 (October): 1–21.

Brinton, Daniel G. 1885. The Lenâpé and Their Legends: With the Complete Text and Symbols of the Walam Olum. A New Translation, and an Inquiry into its Authenticity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. Digitized download: https://archive.org/details/lenpandtheirleg00rafigoog.

Buvit, Ian, Jeffrey T. Rasic, Steven R. Kuehn, and William H. Hedman. 2018. “Fluted Projectile Points in a Stratified Context at the Raven Bluff Site Document a Late Arrival of Paleoindian Technology in Northwest Alaska.” Geoarchaeology 34, no. 1 (January/February): 3–14.

Carmona Moreno, Félix. 1993. Fray Luís López de Solís, O.S.A.: Figura Estelar de la Evangelización de América. Madrid, Spain: Editorial Revista Agustiniana.

Cedrenus, Georgio. 1566. Annales, sive Historiae ab exordio mundi ad Isacium Comnenum usque Compendium . . . Graece et Latine Editi Guilielmo Xylandro. Basil, Switzerland: Ioan Oporinum et Episcopius fratres.

Clark, Jorie, Anders E. Carlson, Alberto V. Reyes, and Dylan H. Rood. 2022. “The Age of the Opening of the Ice-Free Corridor and Implications for the Peopling of the Americas.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 119, no. 14 (March 21): e2118558119.

Davis, Loren G. and David B. Madsen. 2020. “The Coastal Migration Theory: Formulation and Testable Hypotheses.” Quaternary Science Reviews 249 (December): Article no. 106605.

Dover, Robert V. H., Katharine E. Seibold, and John Holmes McDowell. 1992. Andean Cosmologies Through Time: Persistence and Emergence. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Dulik, Matthew C., Sergey I. Zhadanov, Ludmila P. Osipova, Ayken Askapuli, Lydia Gau, Omer Gokcumen, Samara Rubinstein, and Theodore G. Schurr. 2012. “Mitochondrial DNA and Y Chromosome Variation Provides Evidence for a Recent Common Ancestry between Native Americans and Indigenous Altaians.” The American Journal of Human Genetics 90, no. 2 (February): 229–246.

Ellis, Christopher. 2013. “Clovis Lithic Technology: The Devil Is in the Details.” Reviews in Anthropology 42, no. 3 (July): 127–160.

Fladmark, Knut R. 1979. “Routes: Alternate Migration Corridors for Early Man in North America.” American Antiquity 44, no. 1 (January): 55–69.

Flannery, Kent, and Joyce Marcus. 2012. The Creation of Inequality: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Gargett, Robert H. 2012. “The Subversive Archaeologist” (January). http://www.thesubversivearchaeologist.com/2012/01/belated-touchstone-thursday-with-wacky.html.

Goebel, Ted, Heather L. Smith, Lyndsay DiPietro, Michael R. Waters, Bryan Hockett, Kelly E. Graf, Robert Gal, Sergei B. Slobodin, Robert J. Speakman, Steven G. Driese, and David Rhode. 2013. “Serpentine Hot Springs Alaska: Results of Excavations and Implications for the Age and Significance of Northern Fluted Points.” Journal of Archaeological Science 40, no. 12 (December): 4222–4233.

Goldstein, Paul. 2007. “Settlement Patterns and Altiplano Colonization: New Models and Evidence from the Tiwanaku Diaspora.” In Sociedades Precolombinas Surandinas: Temporalidad, Interacción y Dinámica Cultural del NOA en el ámbito de los Andes Centro-Sur. Edited by Verónica Isabel William, Beatriz Nina Ventura, Adriana Beatriz Dallegari, and Hugo Daniel, 155–187. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Buschi.

Griffith, Kenneth C., and Darrell K. White. 2022a. “Chronological Framework of Ancient History. 1: Problem, Data, and Methodology.” Answers Research Journal 15 (November 16): 377–390. https://answersresearchjournal.org/ancient-egypt/chronological-framework-ancient-history-1/.

Griffith, Kenneth C., and Darrell K. White. 2022b. “Chronological Framework of Ancient History. 2: Founding of the Nations.” Answers Research Journal 15 (December 14): 405–426. https://answersresearchjournal.org/tower-of-babel/chronological-framework-ancient-history-2/.

Griffith, Kenneth C., and Darrell K. White. 2023a. “Chronological Framework of Ancient History. 3: Anchor Points of Ancient History.”Answers Research Journal 16 (March 22): 131–154. https://answersresearchjournal.org/ancient-egypt/chronological-framework-ancient-history-3/.

Griffith, Kenneth C., and Darrell K. White. 2023b, “Chronological Framework of Ancient History. 4: Dating Creation and the Deluge.”Answers Research Journal 16 (September 20): 475–489. https://answersresearchjournal.org/noahs-flood/chronological-framework-ancient-history-4/.

Griffith, Kenneth C., and Darrell K. White. 2023c, “Chronological Framework of Ancient History. 5: The Babylonian Dynasties of Berossus.” Answers Research Journal 16 (December 20): 635–670. https://answersresearchjournal.org/archaeology/chronological-framework-ancient-history-5/.

Griffith, Kenneth C., and Darrell K. White. 2024. “Chronological Framework of Ancient History: Parts 1–5. Reply.” Answers Research Journal 17 (October 2): 669–676. https://answersresearchjournal.org/chronology/cfah-1-5-reply/.

Haynes, C. Vance, Jr. 1982. “Were Clovis Progenitors in Beringia?” In Paleoecology of Beringia. Edited by David M Hopkins, John V. Matthews, Jr., Charles E. Schweger, and Steven B. Young, 383–398. New York, New York: Academic Press.

Hiltunen, Juha J. 1999. Ancient Kings of Peru: The Reliability of the Chronicle of Fernando de Montesinos: Correlating the Dynasty Lists with Current Prehistoric Periodization in the Andes. Helsinki, Finland: Suomen Historiallinen Seura.

Hiltunen, Juha, and Gordon F. McEwan. 2004. “Knowing the Inca Past.” In Andean Archaeology. Edited by Helaine Silverman, 237–254. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Hyland, Sabine. 2010. The Quito Manuscript: An Inca History Preserved by Fernando de Montesinos. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University.

Itier, César. 2012. Viracocha o El Océano: Naturaleza y Funciones de una Divinidad Inca. Lima, Peru: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos.

Ives, John W. 2024. “Stemmed Points and the Ice-Free Corridor.” PaleoAmerica 10, nos. 2–3: 108–131.

Jackson, Brittany, and Mark Rose. 2009. “Walam Olum Hokum.” Archaeology, December 4. https://archive.archaeology.org/online/features/hoaxes/walam_olum.html.

Janusek, John Wayne. 2008. Ancient Tiwanaku. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Jeanson, Nathaniel T. 2021. Traced: Human DNA’s Big Surprise. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Johnston, W. A. 1933. “Quaternary Geology of North America in Relation to the Migration of Man.” In The American Aborigines, Their Origin and Antiquity. Edited by Diamond Jenness, 9–45. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Jose ben Halafta, Rabbi. 1998. Seder Olam: The Rabbinic View of Biblical Chronology. Translated by Heinrich W. Guggenheimer. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

Lewis, Martin W. 2012. “Siberian Genetics, Native Americans, and the Altai Connection.” Geocurrents. https://www.geocurrents.info/blog/2012/05/26/siberian-genetics-native-americans-and-the-altai-connection/.

Llamas, Bastien, Lars Fehren-Schmitz, Guido Valverde, Julien Soubrier, Swapan Mallick, Nadin Rohland, Susanne Nordenfelt, et al. 2016. “Ancient Mitochondrial DNA Provides High-Resolution Time Scale of the Peopling of the Americas.” Science Advances 2, no. 4 (April 1): e1501385.

Mallory, J. P. and Douglas Q. Adams. 1997. Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. London, United Kingdom: Fitzroy Dearborn.

McCutchen, D. trans and ed. 1993. The Red Record: The Walam Olum: The Oldest Native North American History. Garden City Park, New York: Avery Publishing.

Midrash Rabbah: Genesis (ca. AD 300–500). 1983. Translated by H. Freedman and Maurice Simon. Vols. 1–2. London, United Kingdom: Soncino Press.

Montesinos, Fernando de. 1882. Memorias Antiguas Historiales y Políticas del Perú. Edited by Jimenez de la Espada. Madrid, Spain: Imprenta de Miguel Ginesta.

Montesinos, Fernando de. 1920 (1967). Memorias Antiguas Historiales del Peru. Translated by Philip Ainsworth Means. London, United Kingdom: Hakluyt Society.

Munoz, Samuel E., Sissel Schroeder, David A. Fike, and John W. Williams. 2014. “A Record of Sustained Prehistoric and Historic Land Use from the Cahokia Region, Illinois, USA.” Geology 42, no. 6 (June 1): 499–502.

National Park Service. 2025. “Beringia, a Shared Heritage.” https://www.nps.gov/subjects/beringia/index.htm.

Newman, Andrew. 2010. “The Walam Olum: An Indigenous Apocrypha and Its Readers.” American Literary History 22, no. 1 (Spring): 26–56.

Oard, Michael J. 2020. “Land Bridges After the Flood.” Journal of Creation 34, no. 3 (December): 109–117.

Pärssinen, Martti. 1992. “Tawantinsuyu: The Inca State and Its Political Organization.” Studia Historica 43. doi:10.2307/27629636. https://www.academia.edu/32268480/Tawantinsuyu_The_Inca_State_and_Its_Political_Organization.

Pitblado, Bonnie L. 2011. “A Tale of Two Migrations: Reconciling Recent Biological and Archaeological Evidence for the Pleistocene Peopling of the Americas.” Journal of Archaeological Research 19, no. 4 (March 12): 327–375.

Ponce Sanguinés, Carlos. 1999. Los Jefes de Estado de Tiwanaku y Su Nomina: un Avance de la Arqueología Política. La Paz, Bolivia: Producciones Cima.

Potter, Ben A., James F. Baichtal, Alwynne B. Beaudoin, Lahrs Fehren-Schmitz, C. Vance Haynes, Vance T. Holliday, Charles E. Holmes, et al. 2018. “Current Evidence Allows Multiple Models for the Peopling of the Americas.” Science Advances 4, no. 8 (8 August). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aat5473.

Pseudo-Philo. 1917 (2004). The Biblical Antiquities of Philo. Translated by M. R. James. Annotated by John Bruno Hare. https://sacred-texts.com/bib/bap/index.htm.

Rafinesque, C. S. 1836. The American Nations; or, Outlines of Their General History, Ancient and Modern: Including: the Whole History of the Earth and Mankind in the Western Hemisphere; the Philosophy of American History; the Annals, Traditions, Civilization, lanuguages, &c., of All the American Nations, Tribes, Empires, and States. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: C. S. Rafinesque. https://archive.org/details/americannations02rafigoog/page/n130/mode/2up.

Sarmiento De Gamboa, Pedro. 1907. History of the Incas. Translated and edited by Clements Markham. Cambridge, United Kingdom: The Hakluyt Society.

Shalley-Jensen, Michael. 2017. The Ancient World: Extraordinary People in Extraordinary Societies. Hackensack, New Jersey: Salem Press.

Szeminski, Jan. 1995. “Los Reyes de Thiya Wanaku en las Tradiciones Orales del Siglo XVI y XVII.” Estudios Latinoamericanos 16: 11–72.

Tweedy, Eric J. 2024a. “Chronological Framework of Ancient History. Parts 1–5. Comments.” Answers Research Journal 17 (October 2): 647–667. https://answersresearchjournal.org/chronology/cfah-1-5-comments-tweedy/.

Tweedy, Eric J. 2024b. “Oard’s Ice Age and Settlement of Northern Europe on Masoretic and Septuagint Timelines.” Answers Research Journal 17 (December 11): 763–783.

https://answersresearchjournal.org/chronology/oards-ice-age-europe-timelines/.

Upham, W. 1895. The Glacial Lake Agassiz. U.S. Geological Survey 25: 1–658.

Ussher, James. 1650 (2003). The Annals of the World. Revised and updated by Larry and Marion Pierce. Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books.

Witherington, Ben, III. 2017. “The Most Dangerous Thing Luther Did.” Christianity Today (October 17). https://www.christianitytoday.com/2017/10/most-dangerous-thing-luther-did/.

Yasinski, Emma. 2022. “New Evidence Complicates the Story of the Peopling of the Americas.” The Scientist 1 (May 2). https://www.the-scientist.com/features/new-evidence-complicates-the-story-of-the-peopling-of-the-americas-69928.

Young-Sánchez, Margaret. 2009. Tiwanaku: Papers from the 2005 Mayer Center Symposium at the Denver Art Museum. Denver, Colorado: Denver Art Museum.

Zakharov, Ilia A., Miroslava V. Derenko, Boris A. Maliarchuk, Irina K. Dambueva, Choduraa M. Dorzhu, and Sergey Y. Rychkov. 2004. “Mitochondrial DNA Variation in the Aboriginal Populations of the Altai-Baikal Region: Implications for the Genetic History of North Asia and America.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1011 (April): 21–35.